24 Ambition

I f somebody has an ambition when she is young, she can work hard to realize this ambition. When she achieves her goals, she may realize they are not what she really wants; her ambition can betray her. Since she will die someday, she cannot avoid being separated from her goals. Her efforts are in vain. She is a part of nature, part of society. She can work toward her goals, and the work itself, the whole effort, is a realization of natural or social beauty. She can enjoy this beauty, this sense of success, but she should not think that she owns this success. The success itself is temporary.

When we set a goal, we often rely on what other people tell us. We have an aim in life, but we have never been there. Since it is not our own experience yet, we do not know how pleasant it can be; we must depend on other people’s descriptions without context. Our own motivations are inspired by other people’s words. We work toward a goal, but when we really achieve it, it may not be what we dreamed. Liezi told a story:

A man was born in Yan, but grew up in Chu. When he was old, he came back to his native place. Passing Jin on the journey home, his fellow traveler fooled him into believing that the city wall was the wall of his home town, and he looked sad. The other traveler told him that one temple was his native temple for the God of land, and he sighed with nostalgia. When the traveler told him that a house was where his parents and grandparents had lived, he began weeping. When he was told that a mound was the tomb of his ancestors, he wailed. The other man roared with laughter and said, “That is the state of Jin, my fellow. I have been joking.” The man felt very ashamed. When at last he arrived at Yan and saw the city wall and its temple for the God of land, as well as the actual abode and tombs of his ancestors, he was no longer that sad. 9

The man from Yan was moved by the tomb that was not his ancestors’, but when he sees the real tomb of his own ancestors, he is not that sad. His feelings are controlled by illusions created by other people.

Confucius, who occasionally reveals a subtle appreciation of the Taoist approach, also realizes that we often have ambitions for the future at the cost of the present. The following classical Confucian story shows some Taoist tendency.

Once when Zi Lu, Zeng Xi, Ran Qiu, and Gongxi Hua were seated in attendance with the Master, he said, “You consider me as a somewhat older man than yourselves. Forget for a moment that I am so. At present you are out of office and feel that your merits are not recognized. Now supposing someone were to recognize your merits, what employment would you choose?”

Zi Lu promptly and confidently replied, “Give me a country of a thousand war-chariots, hemmed in by powerful enemies, or even invaded by hostile armies, with drought and famine to boot; in the space of three years, I could endow the people with courage and teach them in what direction right conduct lies.”

Our Master smiled at him. “What about you, Qiu?” he said.

Qiu replied, “Give me a domain of 60 to 70 leagues, or 50 to 60 leagues, and in the space of three years, I could bring it about that the common people should lack for nothing. But as to rites and music, I should have to leave that to a real gentleman.”

“What about you, Gongxi Hua?”

He answered, “I do not say I could do this; but I should like at any rate to be trained for it. In ceremonies at the Ancestral Temple or at a conference or general gathering of the feudal princes, I should like, clad in the Straight Gown and Emblematic Cap, to play the part of junior assistant.”

“Zeng Xi, what about you?”

The notes of the zither he was softly fingering died away. He put it down, rose, and replied, saying, “I fear my words will not be so well chosen as those of the other three.”

The Master said, “What harm is there in that? All that matters is that each should name his desire.”

Zeng Xi said, “At the end of spring, when the making of the Spring Clothes has been completed, I would like to go with five or six newly-capped youths and six or seven uncapped boys, person the lustration in the river Yi, take the air at the Rain Dance altars, and then go home singing.”

The Master heaved a deep sigh and said, “I am with Zeng Xi.” 10

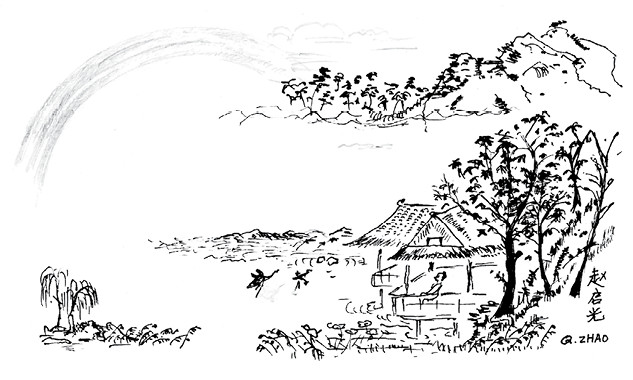

The process is more beautiful than the goal. Many modern girls dream of being a princess, but the more beautiful thing is the process to get there, and not the position itself. Princess Diana was one of the most miserable people in the world, because she reached the goal without the process. The climax of her glory was her marriage. All of her later life was spent paying the price of being a princess without having gone through the process. Most winners of the lottery have lives full of disappointment because they did not have the enjoyment of the process of becoming rich. Wealth is not a bad thing, if it stands at the end of hard work. Remember, the rainbow is more beautiful than the pot of gold at the end of it.

Appreciate, but do not own, the beauty.

The rainbow, colorfully transparent and surrealistically floating, is beyond anyone’s reach. Viewers admire it in the crisp air after the rain, and nobody is so silly as to claim to own it. This is the beauty of the rainbow. The ambition of ownership is the destroyer of beauty.

If you want anything to happen, you must start from the very beginning. No matter how ambitious you are, you cannot build a pagoda from above. Eighty percent of all our energy is spent in the wrong direction. Think before you move forward; sometimes direction is more important than hard work. As a Chinese saying goes, “You cannot lower your head and pull a cart.”

Zhanguo Ce ( Comments on the Warring States ), a book published more than 2,000 years ago, records the following story:

A man wants to travel to the Chu State in the south, but his driver goes north. A stranger asks him, “What are you doing? You want to go south!”

“But I have a very capable driver,” replies the man.

“But the Chu State is in the south.”

“But I have a lot of money!”

“You have a lot of money, but the Chu State is still in the south.”

“I have a fast horse!”

“Yes, you do, but the Chu State is still in the south.”

Here we can see that if the direction is wrong, hard work does not help at all. The driver works harder and the passenger only moves farther from the destination. When the direction is correct, the unforced effort, Wu Wei in this case, will lead the vehicle forward. Wu Wei is not idling but quietly contemplating, musing, and setting a correct direction. The world should realize that a driven worker is not more respectable than a relaxed thinker. Let us leave the thinker alone, maybe she is a direction setter.

According to Lao Tzu, people usually fail when they are on the verge of success. They become overconfident, arrogant, and careless when success is in sight and take the last, but wrong, direction. This is why Wu Wei is important. When you do not know what to do, do nothing and let your mind rest. The mind is more powerful than you know. Take a break and let it work!

Also, remember that the process is more beautiful than the goal. The most dangerous thing is not that you cannot grab the sword. It is that once you have it, you either break it, find that you do not like it, or use it for destruction. The moment you have achieved your goals is the most dangerous time, because you may waste or even abuse the achievements you have worked for years to achieve.

A lonely thinker, a respectable contemplator,

and maybe a direction setter of the world.

N OTES

25 Flying

T o fly has been a universal human dream since antiquity, and so have mythical flying creatures, like dragons. Belief in them has prevailed all over China for thousands of years and has attained a certain reality through historic, literary, mythological, folkloric, social, psychological, and artistic representations. Hardly any symbols saturate Chinese civilization so thoroughly as those of the dragon. Among its many symbolic meanings, the dragon represents a powerful liberation from the bonds of the world, riding on the wind and reaching the heavens. In the air, across the sky, and above the ocean, it effortlessly soars on the wind and disappears among the clouds.

The Taoist imagination enabled the ideal man to soar like a dragon with elevated and sublime spirits. According to a legend in Shiji, Records of the Historian , Confucius once said this of Lao Tzu: “Birds fly, fish swim, animals run. Animals can be caught with traps, fish with nets, and birds with arrows. But then there is the dragon; I do not know how it rides on the wind or how it reaches the heavens. Today I met Lao Tzu. I can say that I have seen the Dragon.” Here Confucius refers to the effortless grace of Lao Tzu, who does nothing and leaves nothing undone.

“How many times do I have to tell you, Billy?

There are no such things as dragons!”

A scene from the most universal dream.

In modern times, humans really can fly. John Gillespie Magee, Jr., was born in Shanghai, China, in 1922 to an English mother and a Scotch-Irish-American father. He dreamed of becoming a pilot and fighting against Nazi Germany, but the United States had not yet entered WWII. As an American citizen, he could not legally fight. He entered flight training in the Royal Canadian Air Force anyway. Within the year, he was sent to England to fight against the German Luftwaffe. John soon rose to the rank of Pilot Officer. On September 3, 1941, he flew a test flight in a newer model of the Spitfire V. As John climbed to a height of 30,000, he was struck with inspiration. Soon after he landed, he wrote a letter to his parents. In the letter, he wrote, “I am enclosing a verse I wrote the other day. It started at 30,000 feet and was finished soon after I landed.” On the back of the letter, he jotted down his poem:

High Flight

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

Sunward I’ve climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth

Of sun-split clouds and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of—wheeled and soared and swung

High in the sunlit silence. Hov’ring there,

I’ve chased the shouting wind along and flung

My eager craft through footless halls of air. . . .

Up, up the long, delirious burning blue

I’ve topped the wind-swept heights with easy grace

Where never lark, or even eagle flew—

And, while with silent, lifting mind I’ve trod

The high untrespassed sanctity of space,

Put out my hand, and touched the face of God.

Just three months later, on December 11, 1941—only three days after the United States entered the war—Magee was killed in a midair crash. A farmer testified that he saw the Spitfire pilot struggle to push back the canopy. The pilot, the farmer said, finally stood up to jump from the plane. Magee, the pilot-poet, was too close to the ground for his parachute to open and he died immediately. He was 19 years old.

As a young man, John Magee seems to have done everything that many “have not dreamed of.” He flew up, up to the “delirious burning blue…where never lark, or even eagle flew.” He tested the limit of ecstasy. The poet here does everything, but he does everything with freedom. He “topped the wind-swept heights with easy grace.” Magee did nothing, but he reached the height of heroism by liberating himself in the air. He gracefully reached heaven like a dragon.

Slipping the surly bonds of Earth.

To “slip the surly bonds of Earth” has long been the dream of Taoism. According to Zhuangzi, Wu Wei, or “doing nothing,” refers to the attitude of the Taoist sage or the “ideal person.” He is not literally doing nothing, but he engages in transparent and effortless activity. In an ideal realm, the ideal person acts in nonaction, relaxes and wanders, roams away with no particular goal. He flies like a bird, floats like a cloud, swims like a fish, meanders like a stream, blooms into life like a spring flower, and falls to death like an autumn leaf. Just like John the airman, he flies his craft “through footless halls of air” with silent, lifting mind.

Wu Wei is associated with the spiritual flying quality of the free person who has overcome the daily bonds of the ego and is able to experience the totality of things. Magee was like Zhuangzi’s sage. He “danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings” and “touched the face of God.” He has done Wu Wei, or doing nothing, and Wu Bu Wei, leaving nothing undone, in a heaven at 30,000 feet.

The first rockets were invented in China. The Chinese invented gunpowder and made firecrackers by stuffing it into bamboo tubes. According to legend, the world’s first rocket scientist was Wan Hu, a Chinese official of the Ming Dynasty. Five hundred years ago, Wan Hu designed a “flying dragon” by binding two large kites and 47 firecrackers to a chair. He asked 47 torch-bearing assistants to light the firecrackers at the same time. They did so dutifully. A thundering roar and fluttering clouds of smoke followed. The smoke cleared, and Wan Hu was no more.

We do not know whether Wan Hu built his rocket out of a Taoist desire to escape from this world or a Confucian desire to serve his nation by inventing a new mode of transport. I prefer to believe he was a Taoist because of his playful imagination and his burning desire to fly into the great nothingness. Did he fly in one piece into the azure sky? The answer is lost in the smoke of antiquity.

Father, are you sure this is the only way to escape from this world?

In Taoism, flying can be reached by imagination. A soaring mind can also lift us from the binding earth. Zhuangzi told a story of a man named Tian Gen, who once asked Wu Ming Ren (Nameless Man) how to rule the world. Wu Ming Ren reproached him for disturbing his spiritual flying, saying, “Go away, you shallow man! Why do you ask such a vulgar question? I was in the company of the creator. When I get bored, I’ll ride on the bird of purity and emptiness, and fly beyond the six ends of the earth, and travel in the realm of nothingness.”

“Students, do not look at her. The Witch of the West belongs to another realm. We have our own Taoist way to fly.”

26 Do Nothing in this World

N ot everybody experiences ecstasy in midair like John Gillespie Magee, but everybody has the same guaranteed ending—death. Should we be afraid of death, that “undiscovered country?” For several thousand years, sages and philosophers have been exploring what we do “over there.” Here, an anonymous person knows what we do there—nothing, and she yearns for it:

On a Tired Housewife

Here lies a poor woman who was always tired,

She lived in a house where help wasn’t hired:

Her last words on earth were: “Dear friends, I am going

To where there’s no cooking, or washing, or sewing,

For everything there is exact to my wishes,

For where they do not eat, there’s no washing of dishes.

I’ll be where loud anthems will always be ringing,

But having no voice I’ll be quit of the singing.

Do not mourn for me now, do not mourn for me never,

I am going to do nothing forever and ever.”

— Anonymous

This tired housewife has a great sense of humor, but at the same time, she is profoundly sad. She cooked, washed, and sewed all her life without any help. Now she yearns for a world where she will do nothing forever. All worries and chores will be gone. She has been too tired, unrewarded, and unappreciated. She begs her friends not to mourn for her. Instead, they should give a standing ovation to the departure of this tired housewife. Lord Byron said, “Sweet is revenge—especially to women.” The tired woman delivered revenge to the world, which required her to do everything by telling the world that she is happy to be dead and doing nothing in the other world.

Life usually lasts less than a hundred years, but death is eternal. No wonder it can seem so much more serene, more real, even more interesting than life. Death started before life and will last after life. We can achieve the serenity of this infinite world by letting life take its natural course. The world is won by those who let it go. Life is won by those who dare liberate themselves to join the universe and follow the philosophy of Wu Wei in life. The tired housewife does not need to die to find the peace she wants. This can be done in this life instead of waiting for the next world. The sky would not fall if she took it easy.

Wu Wei is a behavior that arises from a sense of oneself as connected to the world. It is not built by a sense of separateness, but rather by the spontaneous and effortless art of living, which a pilot or a housewife can both achieve. Through understanding this principle and applying it to daily living, from doing tiring chores to dancing in the skies on laughter-silvered wings, we may consciously become a part of life’s flow. Nondoing is not passivity, inertia, or laziness. Rather, it is the experience of floating with the wind or swimming with the current.

The principle of Wu Wei carries certain requirements. Primary among these is to consciously experience ourselves as part of the unity of life. Lao Tzu and Zhuangzi tell us to be quiet and vigilant, learning to listen to both our own inner voices and the voices of nature. In this way we heed more than just our mind to gather and assess information. We develop and trust our intuition as our connection to the Tao. We rely on the intelligence of our whole body, not only our brain. All of this allows us to respond readily to the beauty of the environment, which of course includes ourselves. Nonaction functions in a manner to promote harmony and balance. In a sense, the housewife’s tiresome life can be as pleasant as Magee’s glide over the cloud. She did not have to wait until the next world. She can do nothing and everything in this world.

27 Walking

W hen I first came to Carleton College, I took a walk with no destination in mind on Bell Field, a sunken soccer field. I circled and circled, as many Chinese people will do for a walk. Two students were sitting on the hill nearby, watching me. Finally, they came to me and kindly asked, “Did you lose something?” From their bemused expressions, I read another, unasked question: “Are you crazy?”

“Thank you,” I said. “I’m just walking.”

As a matter of fact, English does not have a good equivalent for the Chinese word sanbu , loose or scattered steps. I realized later that in the English language, you walk with a goal. Walking in a circle without a destination or purpose seems crazy and like a waste of time. Yet walking without a goal is the best healing practice for your mind, your body, and your soul. You are imitating the basic movement of the universe: a moon circling a planet, a planet circling a sun. One-way walking is normal on earth, something unique for “earth animals,” but it is abnormal in the universe. If we move like the universe, we do as Einstein said: “It is still the best to concern yourself with eternals, for from them alone flows the spirit that can restore peace and serenity to the world of humans.”

“Sir, can we offer you directions?”

Lao Tzu said, “Good running leaves no tracks.” ( Chen, The Tao Te Ching, Chapter 27) The skilled walker just floats through the air without physical or mental tracks. I believe that if you walk with anxiety, with mental knots, you leave invisible tracks of contagious anxiety behind you, infecting anyone who comes across them. Unfortunately, the world is full of tracks of troubled minds, like a freeway during rush hour clogged with harried drivers.

We do a lot of things while walking—too many. We have a goal, a target, or an errand for the walking. We pay too much attention to the goal, too little to the process—and what a pleasant and graceful process it is! We do not allow ourselves to pause, to smell the fresh air, to look at the blue sky, or to restore peace in ourselves. As a matter of fact, we cannot walk, we can only go—go somewhere : go shopping, go to work, or go on an errand. Nevertheless, we should relearn how to walk going nowhere . I call this “meditative walking.” When you practice meditative walking, each step calls you back to the present moment. Each step enables you to connect to the eternal and to create a link between your mind and your body.

Meditative walking brings you to the present, undoing knots in your heart, transforming negative energies to positive. It seems that you are not going anywhere, but you are going here and now. You are engaging in a process without a goal, a doing without achieving. This is walking without going.

Swimming without a goal is beautiful and graceful, almost like flying. Lao Tzu said,

A person with superior goodness is like water,

Water is good in benefiting all beings,

Without contending with any.

Situated in places shunned by many others,

Thereby it is near Tao.

(Chen, The Tao Te Ching, Chapter 8)

When you swim, you are closest to the Tao; you are a king reigning over the vast territory of water, which includes the water outside of you and the water inside of you. The practice of swimming meditation unites you with the water outside in order to restore peace and harmony. Do not count laps, do not count time, and do not worry if people stare at you like you are crazy. You are establishing peace in yourself in the territory of water to which you belong.

Doing nothing not only helps you to be serene and healthy, it can also help you “win,” a word Taoism can playfully accept.

The eagle’s flight is a perfect combination of movement and stillness. If we know how to relax in strenuous actions, we can move ahead, like a cloud floating over the mountains, like a river flowing into the ocean, and like a wild swan flying to the horizon.

In college, I was a champion of short-distance running. With 11.2 seconds, I won first prize in the 100-meter race and broke the record of my college. My secret was doing nothing while doing everything. For self-training, I read all available books on short-distance running. I was impressed by an author who wrote that you should relax your body after you begin. The runner should set off at a blistering pace; then they should relax the body, especially the neck and shoulders, for a few steps and take advantage of the momentum. Here, I found the secret of winning. I learned to give myself a few relaxed “centiseconds” during the tense 11 seconds. After setting off, I even yelled to myself fangsong (relax), and I let the dash become a float. During these 11 seconds, the wind screamed by my ears, the destination was in view, and my competitors were moving back, while I was trying my best to relax. When my friends congratulated me on my championship, I would say in a humble Chinese way, “I did nothing.”

28 Tai Chi Boxing, Doing Nothing

T ai Chi Chuan (Quan), or Tai Chi Boxing or Shadow Boxing, is a Chinese martial art that combines self-defense with healing meditation and breath control. The word chuan (Quan) means “fist,” emphasizing the lack of weapons or tools in this martial art. Tai Chi Boxing is the most common form of Tai Chi. It is practiced by millions of people for its health benefits, stress relief, and relaxation. The slow, low, and weak flowing movements stimulate the flow of energy, chi or qi , in the body for health and longevity. By practicing Tai Chi, one’s body and mind become integrated. Many people enter a state of Wu Wei. Tai Chi is translated as the “utmost pole,” the extreme, the end of the limit. The Tao is beyond the utmost pole. When you reach the end of the limit, you return.

The symbol of Tai Chi is the yin-yang.

The symbol of Tai Chi is the circle of yin and yang, black and white intertwined with each other. In this 5,000-year-old mystifying circle, we do not have a beginning, and we do not have an end. We do not have definition. We do not have a purpose. We do not display.

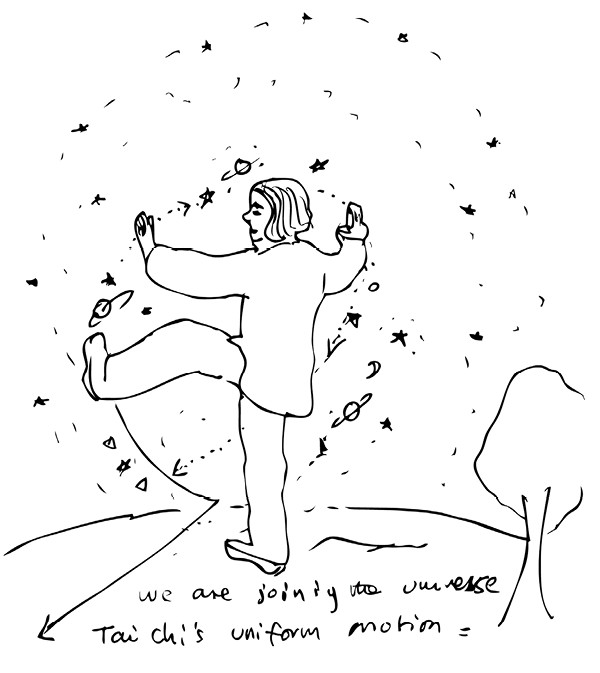

With Tai Chi’s uniform motion, we are joining the universe.

“A journey of a thousand miles must begin with the first step.”

(Chen, The Tao Te Ching, Chapter 64)

Tai Chi’s motion is Wu Wei, doing nothing, because when we do Tai Chi, we move with uniform motion. Uniform motion, according to Newton’s laws, is the same as rest. Newton’s first law of motion, also called the Law of Inertia, states that an object continues in its state of rest or uniform motion unless compelled to change that state by an external force. In our daily environment on the earth, objects slow down because they are compelled to change speed by a friction force. In Tai Chi, there is no friction, no resistance. We continue with uniform motion.

When we have uniform motion, it is the same as resting; we have become stars and planets of nonaction.

Learning the basic forms does not mean that you know Tai Chi. There is always something to improve; think of this as a beginning to a lifelong journey. Knowing the forms is just the beginning.

Attitude in Tai Chi is very important. Do not let your mind wander; feel your place in the universe. Keep in mind these things:

Tai Chi is not a performance. Performance sacrifices the correct way for the entertaining way. Whenever you perform, since your childhood, you have known you have an audience. When you have an audience, you have to show yourself. When you show yourself, you have to be normal. When you are normal, you do things at a normal speed. If you do things slowly, people will think you are not normal, and you are concerned with what other people think. When you do Tai Chi, you should not be concerned with what other people think. You should relax and build a network with the universe. When you build this network, you are spontaneous. Now you do Wu Wei.

People may think you are strange, since they have not seen a human move like this. In the universe, most celestial bodies move in constant motion, in movements with an even speed. We human beings and other animals on the earth act in sporadic motions—very abnormal from the universal point of view. When doing Tai Chi, we move with an even speed, an imitation of the real normal motion of the universe. If others think you are strange, you are performing Tai Chi well.

If you have a dog, perform Tai Chi in front of it. The first time you do it, the dog just barks. It will get annoyed, because dogs do not like abnormal movements. You are not performing well in its eyes, so your dog does not know what to do! Do not worry about your dog, and do not worry about other people. They are both bound to the earth. Tai Chi is not a performance but a return to the natural and universal.

Usually, we change our mindset, and our body language follows. In Tai Chi, we change our bodies, and our minds follow. Grace will follow with the right mindset. When our bodies move like a planet, so will our minds.

In my class, I created an imaginary student whose name was Jenny. Smart and individualistic, she would sometimes challenge my teaching, find the contradictions in my lectures, or over-perform what she had learned. This imagined Jenny became a class joke. Students would start laughing as soon as I said, “Jenny, stop doing that, in Tai Chi 101, we can only float five inches above the ground. How many times does our teacher have to tell you that our motto, opposite to that of the Olympics’ Faster, Higher, Stronger, is Slower, Lower, and Weaker?”

“Jenny, how many times does the teacher have to tell you that we can only float five inches above the ground?”

We should be slower in Tai Chi, because stillness is the essence of the universe. The earth circles the sun, the moon circles the earth, but we cannot even feel the movement. By being still, we can be closer to the essence of the universe.

We should be lower in Tai Chi, because by being low, we come closer to the earth.

We should be weaker, because Tai Chi is not for fighting; it is for peace. Humans used to need strength to survive, attack, and kill. In the beginning, Tai Chi was used for fighting, and we can still see this history in its movements; but it has lost its martial emphasis. Now we advocate the weak as Lao Tzu would, and we use our strength to heal, not to wound. We should be slow, low, and weak—like water. Lao Tzu said:

Nothing under heaven

Is softer and weaker than water,

Yet nothing can compare with it

In attacking the hard and strong.

Nothing can change place with it.

That the weak overcomes the strong,

And the soft overcomes the hard,

No one under heaven does not know,

Though none can put it into practice.

Therefore a sage said:

“One who receives the filth of a state

Is called the Master of the Altar of the Soil and Grain;

One who shoulders the evils of a state

Becomes the king under heaven.”

Straightforward words appear to be their reverse.

(Chen, The Tao Te Ching, Chapter 78)

Low, slow, and weak, Tai Chi brings us back to Nature.

29 Tai Chi Sword, Doing Everything

T ai Chi can be performed with a sword, but we do not want to fight with our swords. We want to play with the clouds and the mountains! Tai Chi Sword is as peaceful as the movement of Tai Chi Boxing, but the illustrative and the dramatic movement of Tai Chi Sword brings the art of Tai Chi to a new peak. The sword is the king of Chinese short-range weapons. It can be deadly in combat. A sword fight requires a level of violence and a mental alertness that not many peace-loving people would want to have; but paradoxically, this practice aims at self-cultivation, longevity, and peace. As Lao Tzu says, “Everything goes toward the opposite extreme.”

A hole in the end of the sword’s hilt is used to attach a long, red tassel that balances the double-edged blade, thus forming a combination of yin and yang. Despite the threatening sword, Tai Chi Sword has more elegant, dramatic, dancelike characteristics. In contrast to the uniform speed of Tai Chi Boxing, Tai Chi Sword allows acceleration and pause during the continuity of a performance. The points of the sword move from various directions with surprises and variety. If we say Tai Chi Boxing is peacefully doing nothing, Tai Chi Sword is more dramatically doing everything.

The imaginary student Jenny would say, “Wait a minute! Last week, you told us to go rambling without a destination in Tai Chi. Now you are telling us to have a target in mind with Tai Chi Sword. Which side are we going to settle on?”

Jenny wants to find out if she should do nothing or everything

with Tai Chi Sword.

Zhuangzi said, “It is different to drift with the Tao; there is neither praise nor blame. Sometimes you’re a dragon, sometimes you’re a snake, floating with time, never focusing on one thing, up and down, using harmony as measurement.”

My answer to Jenny is this: You, disciples, settle between aim and aimlessness, between being good for something and being good for nothing, between Wu Wei and Wu Bu Wei. Basically, Tai Chi Sword is the same as Tai Chi Boxing in that it brings the mind and the body into harmony. The sword helps the performer make an extension of his body. It is essential to enlarge the mind through the tip of the sword. Energy travels from the earth to the feet and is guided through the whole body, through the torso, and to the tip of the sword. It is often said by the masters of Tai Chi Sword that the waist, not the arms, moves the blade. Beginners who move the arm, or disconnect the movement between the arm and the whole body, demonstrate a lack of understanding of Tai Chi principles. The whole body should remain in flux. While the sword spins easily in the air, the performer flies. The feet feel as if they are dragged up by the sword three inches above the ground. This flying would lead the performer to the arch of the sky, to touch the face of the Supreme Being, whether that is God or Nature.

The hand that is not holding the sword should be held with the first two fingers extended and the ring finger and pinky curled in, with the thumb over the ring-finger knuckle. Some people call this hand Secret Sword or Sword Amulet. The two pointed fingers actively cooperate with the hand that holds the sword. They point at the direction the sword would go to lead the performer’s energy and attention to that direction, or deliberately point to other directions to distract the imagined opponents. Thus, the tip of the sword, the tip of the tassel, and the tips of the fingers form three points in a sphere, circling around the body in different directions and balancing the energy. It can be a most elegant image, when a master stands inside these three points with her flexing body changing from standing on her toes to doing a split on the ground. A new dimension, a new magical field is created. This is an ode to possibilities, to courage, and to doing everything possible.

Zhuangzi offers an extraordinary passage about the art of the sword:

The sword of the Son of Heaven... is designed in accord with the Five Phases, assessed by its punishment and bounty, drawn by means of the Yin and Yang, wielded in spring and summer, and strikes its blow in autumn and winter. With this sword you can

Thrust and there’s nothing ahead,

Brandish and there’s nothing above,

Press down on the hilt and there’s nothing below,

Whirl it round and there’s nothing beyond.

Up above, it breaks through the floating clouds; down below, it bursts through the bottom of the earth. Use this sword once, and it will discipline the lords of the states, the whole empire will submit.

The sword of the prince of a state has clever and brave knights for its point, clean and honest knights for its edge, worthy and capable knights for its spine, loyal and wise knights for its hand-guard, dashing and heroic knights for its hilt. With this sword you will

Thrust and there’s nothing ahead,

Brandish and there’s nothing above,

Press down on the hilt and there’s nothing below,

Whirl it round and there’s nothing beyond.

Use this sword once, and it will be like the quake after a clap of thunder, within the four borders, none will refuse to submit and obey your commands.

The sword of the common man is to have tousled hair bristling at the temples, a tilted cap, stiff chinstrap, coat cut up short at the back, have glaring eyes, be rough of speech, and duel in your presence. Up above, it will chop a neck or slit a throat; down below it will burst lungs or liver. This is the sword of the common man, it is no different than cockfighting. In a single morning, man’s fated span is snapped.” 11

We do not fight the natural order of things, nor do we leave our tasks undone. The Common Man will act, but he will act with only his own petty aims in mind. When we carry the Sword of the Son of Heaven, our actions are most effective, because they are done in harmony with the flow of the universe.

Greet people with words, not swords.

I respect you, since you are alive and have a battle to fight every day. But may you stop for a while to smell the flowers between your battles, since you are only here for a short visit. Greet people with words, not swords. Be kind! Everyone you meet on the way has a hard battle to fight.

The world has no room for cowards. We must all be ready somehow to toil, to suffer, to die. And yours is not the less noble because no drum beats before you when you go out into your daily battlefields, and no crowds shout about your coming when you return from your daily victory or defeat.

— Robert Louis Stevenson

A warrior without sword, a hero in daily battlefields.

The distinction between Tai Chi Boxing and Tai Chi Sword represents the contrast of doing nothing and doing everything. Tai Chi Boxing flows with whatever may happen and lets your mind be free. This is Wu Wei, or doing nothing. Yielding is the use of the Tao of Tai Chi. Even in small movements, there is grandeur. Do not hurry, do not worry; you are only here for a short visit. You may not be able to accomplish a grand mission today, but stop by and move along with the ten thousand objects of the universe!

For Tai Chi Sword, you stay centered by completing whatever your sword ventures to do. This is doing everything, or Wu Bu Wei, leaving nothing undone. Reversing is the motion of the Tao of Tai Chi Sword. Beautiful things are all around you: the air is close to you, the sky is above you, and you can even lift your head and see the stars. Your sword cannot touch them, but their beauty is there with you. You can amplify the small and flow with the universe.

The Law of the Unity of Opposites is the fundamental law of the universe. Things that oppose each other also complement each other. Thus, Tai Chi Boxing and Tai Chi Sword complement one another like the two sides of a crystal jade.

N OTES

30 Happiness

H appiness is internal. It does not depend on what we have but on what we are. It does not depend on what we get but on what we experience. Our hearts are lifted when we behold a rainbow, but we do not want to own it. Most of us do not even want to travel to the end of it to find the pot of gold. We do not have to, because we see the beauty shining against the clouds, and that is happiness enough for us. We do nothing with it except let it shine in our hearts without trying to possess it.

Liu An of the Han Dynasty wrote a story about a lost horse:

An old man who lived on the northern frontier of China was skilled in interpreting events. One day, his horse ran away to the nomads across the border. Everyone tried to console him, but he said, “What makes you so sure this isn’t a blessing?”

Some months later, his horse returned, bringing back with her a splendid stallion. Everyone congratulated him, but he said, “What makes you so sure this isn’t a disaster?”

Their household was richer by a fine stallion, which the man’s son loved to ride. One day he fell from the horse and broke his leg. Everyone tried to console the man, but he said, “What makes you so sure this isn’t a blessing?”

A year later the nomads came across the border, and every able-bodied man was drafted into the army. The Chinese frontiersmen lost nine of every ten men. Only because the son was lame did father and son survive to take care of each other.

This story, first told 2,000 years ago, has become a Chinese axiom: “The old man of the frontier lost his horse.” It reminds us that blessing turns to disaster and disaster to blessing; the changes have no end, nor can the mystery be fathomed. Our happiness does not depend on what we own. Things like horses and gold come and go. To be happy, one must understand that the gain and loss of material things is simply an ever-changing flow of the river. There are splashes, rises, and falls, but we should remember a simple axiom that exists in all languages: This also will pass.

Lao Tzu said, “Calamities are what blessings depend on, in blessings are latent calamities” ( Chen, The Tao Te Ching, Chapter 58). The great ocean sends us drifting like a raft, the running river sweeps us along like a boat; but we do not tell the ocean to stop its tides, and we do not tell the river to flow slower. We just join them to celebrate the existence of happiness and freedom. We let water carry our boat to a new adventure. This is why, when we face real ecstasy, we stop doing everything, even holding our breath.

Poetry is the record of the happiest moments of human life. The poet sees the beauty around her, and she wants to put this beauty into a rhythmic pattern that responds to the sight. Poetry is important for all cultures; it has been the center of Chinese civilization for 3,000 years. Chinese officials were poets because of their literary talents, having passed civil examinations on essay and poetry writing. China was a country ruled by poets, many of whom were Taoists—full-time, part-time, real, and pretending Taoists. Observing nature and interpreting life with natural phenomena, they escaped from political, social, and economic pressures.

Rivers flow, boats sail, and the present becomes the past.

This also will pass.

One of China’s most famous Taoist poets, Li Bai (or Li Bo; 701–762 CE ) was known for his carefree lifestyle. Most people agree that he is the best Chinese poet because of his unconstrained and joyous understanding of life against the magnificent background of nature. The magic in his poetry comes from his spontaneous enjoyment of life and nature.

Poem 1: Question and Answer in the Mountains

You ask me why I live in the green mountains.

I smile without answering, but with a heart at leisure.

Peach flowers drift away in the stream;

There is another heaven and earth inside the human world…

If no one else comes to your garden party,

invite the moon as your guest.

Poem 2: Drinking Alone Under the Moon

One pot of wine among flowers

Drinking alone without dear ones

Raising the cup and inviting the moon as a guest.

With the shadow, we have a company of three.

The moon cannot take a sip,

The shadow follows me in vain.

For now, I have the moon and the shadow as my companions,

Taking advantage of the spring while it lasts.

When I sing the moon wanders,

When I dance the shadow scatters,

When we are sober, we enjoy each other’s company,

When we are drunk, we go our separate ways.

We’ll have a cold friendship,

Looking for each other through the clouds in the sky.

Nature is the best company, silent like the bamboo or

clucking like the chicken.

The first poem describes the life of a hermit, an ideal Taoist in Chinese traditional literature. In the mountains, he finds happiness and enjoys himself. “Enjoying oneself” is a wonderful English phrase missing in many languages, including Chinese. Although to “enjoy yourself” means to be happy and enjoy the fun, it literally means finding happiness within yourself. In daily life, many people become burdens on themselves. They need jobs, sports, cards, gambling, and smoking to stay occupied. The Taoists seek a way to enjoy themselves without occupation. They can be alone and be happy by finding company in nature. They are not their own burden.

In the second poem, the greatest Chinese poet is alone and lonely, but in a subtle way, he transforms this loneliness into an ecstasy that merges with the flowers, the moon, and the shadow around him. Using the vocabulary of social life, like “company” and “friendship,” he builds a happy trust with nature and liberates himself from the desire to seek happiness from other people. He admires the moon, and he experiences a kind of happiness as cold as the moonlight.

Li Bai reaches freedom in nature. He expresses his ecstasy in poems just like Zhuangzi did in his philosophical stories. They both found their happiness in nature and threw off the shackles of society. They saw dignity and self-respect in the natural world that was only understood by people who shared the same feelings. Li Bai is like the fish described by Zhuangzi:

Zhuangzi and Hui Zi took a walk along the bank of the river. Zhuangzi said, “The fish swim with such ease. They’re so happy.”

Hui Zi said, “You are not a fish. How do you know they’re happy?”

Zhuangzi said, “You are not me. How do you know I do not know the fish are happy?”

Hui Zi said, “I am not you. Of course I do not know if you know. But you are not a fish. You do not know if the fish are happy. So there!”

Zhuangzi said, “Let’s go to the root of the matter. You asked me how I know the fish are happy. So you agree that I know they’re happy, but you want to find out how I know it? I’m standing here on the bank of the river.”

Fish are content because they are doing what they are supposed to do. They swim, bubble, and never dream of being something else. Li Bai with his moon, the horse with its grassland, and the fish with its water all reach the realm of happiness. They do not need other people’s approval, so they are not the prisoners of public opinion. Happiness is found within; material pleasure and public admiration come from the outside. The inner happiness always surpasses the superficial enjoyment.

Inner happiness demands a calm and individual environment. This environment liberates us from the anxieties caused by our daily necessities. Anxiety is crucial for survival—but only in quick flashes: It damages one’s inner health and society’s harmony in the long run. Calmness widens wisdom, expands tolerance, and increases health. Quiet joy strengthens our existence and allows us to make a contribution to the world. When we are frightened, angry, or depressed, we shrink into an invisible shell around us, but at the same time, we project a dark cloud onto others surrounding us. As a Chinese saying goes, “One sad person sitting in the corner makes all the people in the room feel unhappy.” In contrast, a happy person spreads the aroma of flowers, the shadows of the rainbow, and the individual calmness to benefit the collective.

A society is composed of individuals, and each individual is responsible for the group status. Philosophers have talked for centuries about altruism—sacrificing oneself for society. While we new Taoists agree with this idea of selflessness, I should add that each individual’s mood alone determines the world’s collective mindset. It would be very dangerous for an unhappy person to hold power, because he can make the world join his misery. History has proved this again and again. Just like the people in power, each one of us can impact larger humankind. If you make yourself happy and healthy, you will add one happy and healthy grain to the ocean of the world. Sometimes, you feel that you are doing nothing for the human race beyond being happy yourself; as a matter of fact, you are doing everything for its harmony. Your status of cheerful mind will add a colorful band to the multicolored rainbow of the world. This kind of Wu Wei is also a Wu Bu Wei.

Being happy is natural. You will be happy if you let your mind perform Wu Wei. European and American culture is a culture of guilt. People are taught to fear the punishment of an invisible hand. Shrug off the guilt that you have allowed the invisible force to place upon you. You are limitless. There is no happiness that you cannot achieve. Chinese culture is a culture of shame. People are taught to fear losing face. Throw away the shame you have allowed the visible society to place on you. There is no sadness in life that cannot be reversed.

31 No Regret

Reach the pole of emptiness,

Abide in genuine quietude.

Ten thousand beings flourish together,

I am to contemplate their return.

Now things grow profusely,

Each again returns to its root.

To return to the root is to attain quietude,

It is called to recover life.

(Chen, The Tao Te Ching, Chapter 16)

H ave no regret; you are not responsible for everything that has happened to the world. You are not responsible for everything that has happened to you and your family. You are a drop of water in the ocean, and your position is decided by the movement of a body trillions of times larger than you. Your best relief is to realize you are not a god. Nobody says that they are a god, but many people believe that they have the ability of God to control everything around them. Therefore, they regret that things do not happen in the way that they would like.

Every night, when you take off your socks, please leave all your problems on the floor with them. Have no fear, your socks will not be lost, and the world will come back to you when you put the socks back on the next morning. Your day is done. You are like a ship drawn to the harbor, like a seagull listening to the evening music of the tide. You are like an autumn leaf falling to the earth, like a homesick child returning home. Be still and be peaceful when you enter the sweet world of doing nothing. You have to leave everything, everybody, and every worry behind you. Lao Tzu said, “Reach the pole of emptiness, abide in genuine quietude. Ten thousand beings flourish together, I am to contemplate their return.” ( Chen, The Tao Te Ching, , Chapter 16) When you go to sleep, enter the void, join the stillness and quietness.

The most valuable thing is life; we only get one. At death, a person should be able to say, “I am familiar with this, because I have practiced it every night by leaving everything behind me before going to bed. I did something, and I am going to do nothing. I did not have regret all my life, and I do not have it now.”

Regret lurks behind your decisions. Your idea may start out like spring flowers ready to bloom. As soon as the decision is made, there is a crash of thunder. Regret comes in like a summer storm, crashing along with rain so thick that the flowers in your mind are drenched. Then there comes a gentle lament, like an autumn drizzle, that whips the surface of your heart, until repentance, like winter snow, floats down and seals your bleeding wounds.

Lao Tzu said, “No action, no regret.” Action causes regret, because no single action can be exactly correct the first time. The only way to do nothing wrong is to do nothing. Lao Tzu’s “no action, no regret” reflects his theme of Wu Wei. Wu Wei, in this case, is not to avoid decisions in order to avoid regret, but to flow like a river from one correction to another. Correct, as an English adjective, means making no mistake. The English word correct, as a verb means to change something in order to make it right. Therefore, to be correct, one should continuously correct oneself, instead of bemoaning past mistakes.

This is, as a matter of fact, doing everything. When we walk, we move one foot forward. Soon the direction is wrong, and we have to move it backward. Do we regret that we moved the foot wrongly first time? No. We just constantly change the direction of our two feet, and the whole body moves forward smoothly. Our feet are doing everything (Wu Bu Wei) by moving in opposite directions, and our body is doing nothing (Wu Wei) by moving forward. Therefore, our minds have no regret, because they allow those contradictions to proceed naturally.

Everything will resolve itself sooner or later. This is the way of the Tao. Walk through life without fear for the future or regret for the past. Practice being nothing. In being nothing, you will turn into everything without fear. Watch the clouds in the dawn. As they pass the rays of morning sun, they are tinged but unruffled, penetrated but undisturbed. When they pass the mountains and gorges, they are neither elated by the mountains nor depressed by the ravines. They seem to do nothing but have actually done everything. The clouds will never fear floating toward the peaks ahead, nor will they regret having passed over a valley. This is the mind of Wu Wei and Wu Bu Wei: never elated nor depressed, but rather always flowing at peace.

Watch the way a stream flows effortlessly and passes over the rocks that get in its way. The rocks on the bottom make the limpid water bubble melodiously. Obstacles, like rocks in the stream, can make the path of life more beautiful, so that James Maurice Thompson can say, “Bubble, bubble, flows the stream, like an old tune through a dream.” That is the way of life, unencumbered by little impediments. However, the stream takes a bend or diverges around rocks. Water, as Lao Tzu said, “overcomes but never argues, benefits but never claims the benefits.” It makes the best of the situation. Overcoming, giving up, doing nothing, and doing everything, the stream bubbles forward without fear or regret. This is what life should be.

Once I asked my father to write something in my notebook. This is what he wrote:

To Qiguang:

Before I turned 80 years old, I used to have a motto: Be strict with yourself and lenient towards others. Now that I am 80 years old, I have a new motto: Be lenient with yourself and lenient towards others. I do not know whether I can correct myself at this age.

Dad, 1997

A very wise man, a professor of physics, and the dean of a well-known university, my father had spent 80 years learning how to treat himself and others: We should treat ourselves with the same forgiving compassion as we give others. Nothing in the world is without flaws, so be tender and kind to others and yourself when you or others stumble. Let us walk our own way, change the direction of our feet, and let others talk. Correct, change, and live without regret, and let the universe follow its own course.

32 Life and Death

Heaven and earth are long lasting.

The reason why heaven and earth are long lasting:

Because they do not live for self.

Therefore they last long.

Thus the sage puts his body behind,

Yet his body is in front.

He regards his body as external,

Yet his body remains in existence.

Is it not because he is selfless

That he can fulfill himself.

(Chen, The Tao Te Ching, Chapter 7)

T o achieve longevity, we must join the universe. To join the universe, we must think in reverse. Sometimes the Tao sounds like nonsense, but if we think outside the box, it becomes the greatest sense.

The world is divided into opposites. Everything has two sides that coexist. When one side is denied, it develops into the other side. To go forward, we must go backward; everything requires an opposite. When you walk, one foot moves forward and the other pushes back. It is the back foot that pushes your body forward. In aging, the more you stay behind—acting slowly, staying young—the longer you live. In other words, by staying behind, you get ahead.

This process should be natural, effortless, and not achieved through force. When forms change, they can transform without changing their structure, like clouds or flowers.

At birth a person is soft and yielding,

At death hard and unyielding.

All beings, grass and trees, when alive, are soft and bending,

When dead they are dry and brittle.

Therefore the hard and unyielding are companions of death,

The soft and yielding are companions of life.

Hence an unyielding army is destroyed.

An unyielding tree breaks.

The unyielding and great takes its place below,

The soft and yielding takes its place above.

(Chen, The Tao Te Ching, Chapter 76)

Lao Tzu’s wisdom can be seen in numerous phenomena. Everyone has teeth and a tongue. Which is softer? The tongue, of course. Which falls out first? Of course, the teeth. Have you ever heard of anyone’s tongue falling out?

One of Aesop’s famous tales, “The Oak and the Reeds,” reflects the same concept. A very large oak was uprooted by the wind and thrown across a stream. It fell among some reeds, which it thus addressed: “I wonder how you, who are so light and weak, are not entirely crushed by these strong winds.” They replied, “You fight and contend with the wind, and consequently you are destroyed; while we, on the contrary, bend before the least breath of air, and therefore remain unbroken, and escape.” We yield and we live. We yield more, and we live longer. However, death will come to us anyway.

Which is more normal, life or death? If life is normal, why have humans not found life anywhere in the universe except the earth? If death is so abnormal, why does the whole starry sky radiate the shining light of nonlife?

If life is normal, why does it belong to you for only 80 or 90 years, while death embraces you for the eternities before your birth and after your death?

The lifeless surface of Mars is normal. Its scenery, waterless and lifeless, is more representative of the universe than the Earth’s. The wet surface of the Earth is the anomaly. Life, as far as we know, could not exist without liquid water, which is rare in the universe. No water, and consequently no life, has been found on other planets. Therefore, death is more the essence of the universe. When we die, we just return to normal. We should not cling to the temporary abnormality that is life and refuse the eternal and universal norm.

The person who fears death is like the child who has forgotten the way home. Liezi told a story about Duke Jing of Qi:

Duke Jing climbed up Mount Niu and looked over his capital. He began to cry. “What a magnificent capital! How can I die and leave behind this flourishing town, these verdant forests?”

His two ministers, Shi Kong and Liang Qiuju, also began to weep. “Thanks to Your Highness, we can feed ourselves with our simple food and get around on our humble carriages. Even though we live only modest lives, we do not want to die! And the thought of our lord dying is unbearable!”

Yangzi stood nearby, laughing into his beard. Duke Jing frowned. Wiping his eyes, he turned to Yangzi. “I am quite sad here, and Shi Kong and Liang Qiuju are weeping with me. Why are you laughing?”

“If a worthy sovereign were to reign forever,” said Yangzi, “your grandfather or Duke Huan would still be king. If a brave ruler were to reign forever, Duke Zhuang or Duke Ling would still be our lord. If any of these men were still in power, you would never have succeeded to the throne. Your Majesty might be farming in the fields in a straw coat and bamboo hat, without any time to ponder your death. Reigns have followed reigns until at last your turn came, and you alone lament it. I laugh because I’m looking at an unjust lord and his two yes-men.”

Duke Jing was ashamed. He penalized himself with one cup of wine and his attendants with two.

Zhuangzi once told a story:

When Zhuangzi’s wife died, Huizi went to console him. He found Zhuangzi sitting cross-legged, drumming on a pot and singing. Huizi said, “You lived with her and she raised your children. Now she is dead. It would be bad enough if you didn’t cry. But now you are drumming and singing. Isn’t this too much?”

Zhuangzi said, “Definitely not. When she first died, how could I not mourn? Then I realized there was no life in the beginning. Not only no life, but there was no shape. Not only was there no shape, but there was no energy. In the subtle chaos, changes happened. Energy emerged. Energy became shape, shape became life, and now life has become death. This is just the same as the succession of spring, summer, autumn, and winter. My wife was sleeping calmly in a big hall, and I followed her wailing and crying. Then I realized that I did not understand the rules of life. So I stopped crying.”

Should we cry or laugh over the city we will

lose some day because of death?

The message of Zhuangzi’s story is consistent with that of numerous Taoist stories: death is a natural return to peace and eternity. However, if Taoists are so comfortable with this “big return,” why are they so obsessed with longevity and immortality? The Taoist tradition is probably the most famous in the world for its pursuit of the elixir of life through alchemical “miracle drugs.” If they were not afraid of death, why did they work so hard to avoid it?

You can linger at the top of the mountain and wait for the sun to set, but that does not mean you are afraid of going home to the valley. Taoists love life, but they do not fear death. Their search for immortality comes from a desire to stay a little longer in the lively and familiar realm of life, not from a terror of the unknown and quiet domain of death.

Zhuangzi celebrates his wife’s return to Nature.

Which is more interesting, here or there?

We will only be in this world for a short time, but we will be in the other world forever. Death must be interesting, because we have never experienced it; but life is interesting, too, because we have been there, done that. We want to enjoy the adventure as long as possible and do everything before we do nothing.

If life is a dream, let us keep the dream long and sweet. If life is a game, let us make it fun. If life is a one-way journey, let us stop, go outside, and enjoy the scenery. Why hurry? Why always ask, “Are we there yet?” With a healthy understanding of death, we can have a long, healthy, and fearless life.

The barrier between life and death is not absolute. Really, we do not understand death at all. Without knowing anything about it, how do we know that it is not better than life? If we understood death, we would not cry over it. We are not afraid of death; we are afraid of the unknown.

In the Jin dynasty (265–420 CE ), when Taoism was not only a theory, but was also practiced by many scholars as a way of life, there was a well-known group called “the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Forest.” Among the seven sages, Liu Ling was the one least interested in worldly affairs. According to History of the Jin Dynasty, Liu Ling was ugly, free-spirited, quiet, and socially awkward. His spirit soared through the universe and did not distinguish between the ten thousand objects of the world. When he met two other sages of the bamboo forest, Ruan Ji and Ji Kang, the three of them were pleasant and carefree and entered the forest hand in hand.

Liu Ling’s instructions: “Bury me where I fall.”

According to Shishuo Xinyu, a book of historical anecdotes by Liu Qingyi (403–444 CE ), Liu Ling often took off his clothes and drank wine at home. When people saw him and laughed, he answered, “I take heaven and earth as my house, my house as my trousers. What are you doing in my trousers?” He did not care about property, and often he rode in a small cart with a bottle of wine, followed by a boy carrying a hoe. His instructions to this boy were, “When I die, bury me where I fall.” He paraded around with a boy with a hoe to announce that death is not something to be afraid of, but something as normal as life, perhaps even more normal.

A strong man can carry away our boat no matter how deeply

we hide it in the valley.

Zhuangzi considers death a natural change of small forms in the infinite universe:

The huge clump of earth carries my body, puts me to work all my life, nurses me through old age, and lays me to rest with death. Therefore, the one who can give me life can also give me death. You hide your boat in a valley and your fishing tackle in a marsh, and you think it’s safe, but at midnight a strong person can carry them away without your knowing it. It’s proper to hide a small thing in a big thing, but you still may lose it. If you hide the world in the world, you will not lose it. This is the universal law. People are happy when they get a body, but the changes of the body are endless; therefore, the happiness is limitless.

When the day comes to die, we are very afraid. We want to own, to cling to, this thing we call life, but it is only one of millions of transformations. Leaves fall, the sun sets, stars burn out, and we die. Life and death are different stages of the same process. Therefore, if you think well of life, you must think well of death.

Before I leave this world, I am never going to say,

“I didn’t do this”or “I regret I did that.” I am going to say:

“I came, I went, I did nothing, I did all.”

Appendix A

When the Red Guards Knock

A ll incoming Carleton freshmen are given a common reading book to discuss when they arrive at college. In 2003, that book was Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress, and Qiguang Zhao was asked to speak at the opening convocation about the book. The following is an excerpt from that speech, given at Skinner Memorial Chapel at Carleton College on September 11, 2003:

Archimedes once said, “Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it, and I shall move the world.” But where should we place this fulcrum?

Physics tells us that the longer the distance between the two objects, the more powerful the lever. We must build our lever on our connections to the unfamiliar world of nature, beauty, and our fellow humans. On that solid ground, we can move the world.

I am a witness to that power of connection. When I was just about your age, I experienced China’s Cultural Revolution. The Cultural Revolution was actually a revolution of anti-culture, which attempted to create a proletarian revolutionary culture by cutting all connections between modern China, traditional China, and the rest of the world.

At the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, the Red Guards searched houses for “bourgeois books and objects.” The first group who came to my parents’ house was a group of college students. They were students of my parents, who were both professors of physics. One evening, the Red Guards knocked loudly at our front door. At that critical moment, I remembered that my mother had a diary which would have been extremely dangerous if it fell into the hands of the Red Guards. I grabbed the diary, and rushed out our back door just as the Red Guards were entering the front door. I ran for a mile and ducked into a public restroom.

The restroom was quiet. The moon and stars shone through a window overhead; I could hear the familiar lyrical chirpings of the crickets and the unfamiliar militant songs of the marching Red Guards. I looked at the well-kept diary. I wanted to keep it alive in my heart before it sank into oblivion. Under the moonlight, I quickly read my mother’s diary, then tore it off page by page and flushed it down the toilet. Most of the diary was written in exquisite Chinese calligraphy. Parts of it were written in English, which I could not read at that time. In two hours, I finished the job and learned for the first time how my mother grew from a remote countryside girl into a professor of physics, a very rare success in her time. In a nation full of wars, famine, and revolution, my mother was motivated to connect herself with the world through the pursuit of knowledge. She had found solid ground to stand on in an unpredictable time.

I left the restroom and looked up at the stars in the night sky. They were tranquil, mysterious, and extremely beautiful, forming a sharp contrast to the dark earth. When I returned home, the Red Guards were gone. My parents’ house was a mess, but strangely, though their personal and academic writings had been taken away, most of my parents’ thousands of books were untouched. My mother was relieved to learn that her diary was destroyed instead of being taken by the Red Guards.

“They are my students in the physics department,” my father said. I did not know whether he was rejoicing over the limited damage or lamenting the violation of a sacred Confucian relationship, that between teacher and students. I only understood his comment many years later, after the Cultural Revolution, when my father became the dean of the University. The first policy he suggested was to require science majors to study humanities and humanities majors to study science. The Red Guards had allowed themselves to be led toward destruction because they lacked comprehensive knowledge of the world and a sense of history. These days, we often talk about good and evil. I believe that evil occurs when ignorance and power meet.

This house search was just the beginning; more groups of Red Guards came in the following few days. The newcomers were mostly high school students. They were more violent and burned nonrevolutionary books. My family’s decision was probably unique during the Cultural Revolution: when the Red Guards knocked, we would turn off the lights and not open the door. Group after group of Red Guards passed by our dark windows or pounded on our door but left without breaking in. They were not thorough revolutionaries, I guess.

For many nights, while hearing the pounding on the door—the ugliest noise ever made by men—we sat quietly among books written by the most beautiful minds of the world: great books by Li Bai, Confucius, Lao Tzu, Chang Tzu, Einstein, and Shakespeare. We took great risks in order to protect those books. House searches stopped in a few weeks, but the Cultural Revolution was to continue for 10 more years, with schools closed and most books banned. Fortunately, our books remained, and we remained connected to the world. My family defeated the Cultural Revolution in an isolated battle. During China’s darkest years, I found comfort and inspiration among those books of science, literature, and history. They were my solid ground for connections.

Even today, I like to stay among books and journals in a library, reading, researching, and writing as if behind the Great Wall: safe against the sound and fury of the world. Sometimes I just sit quietly with a book on my lap, trying to connect myself to the mysterious universe or looking through the window to the horizon, as if there is something between the sky and the earth. (I call it thinking, but my wife calls it wasting time). I like to sit in a sanctuary of learning, where mellow silence reigns and I do not hear the piercing pounding on the door.

But I would like to warn you today, especially after the events of September 11: Please do not take your sense of safety for granted. No culture is immune to disasters. If you allow yourselves to be disconnected from the world, you may hear that ugly knocking at your door.

Appendix B

In Memory of Hai Zi, Who Died for Beauty

H ai Zi (1964–1989) was an ephemeral star among the “obscure poets” that emerged after China’s 1979 reforms. He dazzled the world twice: the first time when he was accepted by the prestigious Beijing University at the age of 15, the second time when he committed suicide by laying himself on a railway track at the age of 25. Between these two events, he left a bright trail that is composed of 2 million characters of poetry and prose.

Hai Zi was not my friend when he was alive, but he is now in his death. According to About the Death of Hai Zi by his best friend Xi Chuan, Hai Zi carried four books to the railway tracks: the Bible, Thoreau’s Walden , Thor Heyerdahl’s Kon-Tiki: Across the Pacific by Raft , and Selected Novels of Joseph Conrad . I was saddened and flattered when I saw the title of the last book that Hai Zi took to another world, because I compiled, cotranslated, and prefaced the Selected Novels of Joseph Conrad . Before leaving for the United States in 1982, I handed the manuscript to the publisher, and I had scarcely heard anything about it after that. Now I received the most overwhelming feedback that an author or translator can hope for. Hai Zi is no stranger anymore. I did not know I had such a sincere friend and fellow traveler. Together we penetrated the heart of darkness and sailed through a typhoon. We went there together. We both decided we liked the beauty in those places. I left, but he stayed there forever.

Hai Zi died in the line of beauty just as some martyrs die in the line of duty. Beauty’s way of treating us is different from duty’s way. Ellen Sturgis Hooper’s (1816–1841) poem discusses the relationship between duty and beauty:

I slept, and dreamed that life was Beauty;

I woke, and found that life was Duty.

Was thy dream then a shadowy lie?

Toil on, poor heart, unceasingly;

And thou shalt find thy dream to be

A truth and noonday light to thee.

Duty commands, beauty inspires. Beauty is freedom; duty is constraint. Yet our relationship to beauty is the same as our relationship to duty. We can reject beauty’s appeal, as we can reject duty’s command; yet duty, like beauty, cannot be rebuffed with impunity. Hai Zi rebuffed duty in the name of beauty. He paid for beauty with the dearest price—his life.

Hai Zi is a quixotic hero. He began by testing his mind against the world and ended by destroying his body for spiritual freedom. He believed that he could shape Chinese reality into the foreign images of the Messiah’s paradise, Thoreau’s Walden Pond, Heyerdahl’s raft, and Conrad’s ocean. Like Don Quixote, he was doomed to fail heroically. This Chinese knight-errant broke himself against the bars of his self-built prison. He belongs to no world, neither foreign nor Chinese. He focused too much on his spiritual odyssey without preparation of his sailing skills. He loved the ocean, but he could not swim. He loved romance, but he could not dance. He loved the earth, but he could not ride a bike. He loved life, but he could not live. He loved beauty, and he succeeded in creating a unique and original world of words and rhythms. In that sense, he is triumphant.

Hai Zi must have read the following epitaph inscribed on Conrad’s gravestone at St. Thomas Church, Canterbury, England. I translated and quoted it in the preface of Selected Novels of Joseph Conrad :

Sleep after toyle, port after stormie seas,

Ease after warre, death after life, does greatly please.

I believe this poem by George John Spencer did not cause Hai Zi’s death but confirmed his desire to find rest in eternity. He chose to die for beauty, just as some people choose to die for truth. Hai Zi’s epitaph should be Emily Dickinson’s poem:

I died for beauty but was scarce

Adjusted in the tomb,

When one who died for truth was lain

In an adjoining room.

He questioned softly why I failed?

“For beauty,” I replied.

“And I for truth—the two are one;

We brethren are,” he said.

And so, as kinsmen met a-night,

We talked between the rooms,

Until the moss had reached our lips,

And covered up our names.

Or Tao Yuanming’s, “Lament”:

What you can say about death

Just identify the body with the mountains

Or, more properly, Hai Zi’s own poem; “Spring, Ten Hai Zi”:

Spring. Ten Hai Zi all resurrected.

In the bright scene

They mock at this one barbaric and sad Hai Zi

Why on earth do you sleep such a dead, long sleep?

Spring. Ten Hai Zi rage and roar under breath

They dance and sing around you and me

Tear disheveled your black hair, ride on you and fly away,

stirring up a cloud of dust

Your pain of being cleaved open pervades the great earth

In the spring, barbaric and grief-stricken Hai Zi

Only this one is left, the last one

A child of dark night, immersed in winter, addicted to death

He cannot help himself, and loves the empty and cold village

There crops piled high up, covering up the window

They use half of the corn to feed the six mouths of the family,

eating and stomach

The other half was used in agriculture, their own procreation

Strong wind sweeps from the east to the west, from the north to the south, blind to dark night and dawn

What on earth is the meaning of dawn that you spoke of? 12

Hai Zi did what he said and killed himself near the starting point of the Great Wall, where the mountains meet the ocean. His death was a gallant and romantic declaration of his passions, devotions, and beliefs. People finally believed he meant what he had “roared” in his poems, when he willingly returned to the mountains and ocean.

Poetry hides behind the opening and closing of a door, leaving those who look through to guess about what could be seen when the door was open. Hai Zi’s poems, like the marks left in the snow by goose tracks, are the traces of his life. Now, let us open the door and let our ephemeral star be seen.

N OTES

Appendix C

Student Contributions

I n a recent class, 59 students of Carleton College, all members of Qiguang Zhao’s course, The Taoist Way of Health and Longevity: Tai Chi and Other Forms, were divided into six groups and wrote their own manifestos of Applied New Taoism.

Students were also asked to keep a journal of their reactions to the class lectures. The included excerpts from group manifestos and class journals are the products of ten weeks of reflection on both Taoist philosophy and how to apply that philosophy to modern life. The following are their words, either as a group or as individuals.

Student Groups :

Ganbei:

Caitlin Bowersox

David Chin

Rachel Danner

Lianne Hilbert

Craig Hogle

Karen Lee

Matthew Shelton

Like Water:

Naomi Hattori

Aaron Kaufman

Marie Kim

Paul Koenig

Nora Mahlberg

Nelupa Perera

Charles Yi

Old Fishermen:

William Bennett

Philip Casken

Anna Ing

David Kamin

Sophie Kerman

Greg Marliave

Carisa Skretch

Andrew Ullman

The Place Where the Water Meets the Sand:

Becky Alexander

Matt Bartel

Elizabeth Graff

Mark Stewart

Aaron Weiner

Kristi Welle

Katie Whillock

The Sorting:

Alex Baum

Jean Hyun

YoonJung Ku

He Sun

Chris Young

Xiuyuan Geoffrey Yu

The Sound of One Hand Clapping:

Jacob Hitchcock

Anthony McElligott

Lauren Milne

Megan Molteni

Emily Muirhead

Peter Olds

Sam Rober

The concept of Wu Wei is illustrated by the tale of two men stranded in rapids. The first, being too old and weak to fight the current, lets it carry him downstream. By surrendering to the current, he is swept out to calm waters. The second man tries to fight the current and drowns. The old man discovered the nature of water, became water, and was brought to safety. You cannot fight nature; it is arrogant to think that you can change the path of the eternal.

—The Sound of One Hand Clapping

By attempting to “return to the source,” we are trying to attain a higher state of thinking, a state of nothingness. It is not a state that implies ignorance or pessimism, but a state that rejects attempts to regulate society or go against the natural flow.

—Ganbei

Not every problem needs fixing, and not everything that looks wrong is broken.

—Alex Baum

We are like a drop of water in a river. We do not notice that we are moving, because the rest of the water drops are also moving. We strive to move ourselves when all we really need to do is rest and move with the flow of the universe.

—Dan Edwards

We are on a rambling path; we should pay attention to the present. There should be a balance between understanding that we are part of a whole, stretching across time and space, and realizing that we are limited in some regard to our time and space. To ignore this is to ignore where our rambling path has taken us.

I consider it like a great mural: for example, the Sistine Chapel. Certainly Michelangelo had a sense of the work as a whole, but at the same time, each individual part needed special care and attention in order for the whole to succeed.

—Greg Marliave