Imagination is everything. It is the key to coming attractions.

—Albert Einstein

Frail and slight, a quiet woman shuffled up from the back of the room and stood in front of me at the microphone. “My name is June,” she said. “I don’t believe in this energy stuff, and if you don’t want to work with me, I’ll sit down again.”

In front of us, the large conference room was packed. Every seat was taken, and many more people stood in the back of the room. The air was hot, as the crush of bodies overwhelmed the air-conditioning system. Everyone seemed to be holding their breath. I had just concluded a lecture on the history of energy in medicine and psychology. I then asked for volunteers to demonstrate Energy Psychology methods, so that the audience could witness how they worked in real life.

I reassured June that while there were no guarantees that Energy Psychology could help her condition, I’d be happy to try. She told us that her left shoulder was frozen. I asked her to demonstrate, and she could only move her left hand a couple of inches forward and a couple of inches to the side.

I asked about any emotional issues that might underlie her physical complaint. June told us, in a monotone, that her adult son had been kidnapped while on a mission as a peace worker in a third-world country. His kidnappers held him for several months, and finally killed him. She was in touch with the U.S. State Department throughout the ordeal, and finally received a phone call from a consular official to tell her that her son’s body had been found. She had developed many physical problems during her son’s captivity, one of which was that her shoulder froze up. She finished by telling us, “Today is the ninth anniversary of his death.”

I asked her about the emotional intensity of each step of the tragedy, asking her to rate them on a scale of zero to ten, with zero being no intensity, and ten being the maximum possible intensity. After listening to her carefully, I finally decided to work with June on the phone call from the State Department, which she said was a seven in intensity. I then performed a very fast and basic emotional energy release technique called EFT (Emotional Freedom Techniques), used by thousands of doctors and therapists worldwide, as she thought about the phone call. “Rate the intensity again,” I asked, and she reported that it had gone down to zero.

“How’s your shoulder doing?” I asked. She hesitantly moved it forward. It went farther and farther. She raised it up all the way, till it was perpendicular to her body. She began to swing her arm around in circles. Her eyes opened wide, and she stared at the swinging arm as though it were an alien oozing out of a spaceship.

After the lecture ended, June walked up to me in the hallway, exuberantly swinging her arm around and around. Her face was wreathed in smiles, her eyes lively, her voice sparkling. “I felt so horrible this morning I didn’t want to come to the conference,” she confided. “I was carpooling with two friends, and when they arrived at my house, they dragged me out of bed and made me come here. I can’t believe what just happened.”

“Usually, my logical mind can’t believe it either,” I reassured her. “Nevertheless, when you use these energy techniques, such shifts become routine.” Although they seemed miraculous to my skeptical brain when I first witnessed them, I now understand that they are based on sound medical and physiological principles, and they have more to do with biology than magic.

Turning Gene Research into Therapy

From all around the world, in virtually every field of the healing arts—from psychiatrists to doctors to psychotherapists to sports physiologists to social workers—stories like this are being told, as the world of psychology and medicine begins to awaken to the potential of energy medicine and its effects on the expression of our DNA. They are the first loud reports of a revolution in treatment destined to change our entire civilization, reaching into every corner of medicine and psychology…and beyond them into the structures of society itself. In the space of one generation, we have discovered, or rediscovered, techniques that can make us happier, less stressed, and much more physically healthy—safely, quickly, and without side effects. Techniques from energy medicine and Energy Psychology can alleviate chronic diseases, shift autoimmune conditions, and eliminate psychological traumas with an efficiency and speed that conventional treatments can scarcely touch.

The implications of these techniques—for human happiness, for social conflicts, and for political change—promise a radical positive disruption in the human condition, one that goes far beyond health care. They hold the promise of affecting society as profoundly as the scientific and artistic breakthroughs of the Renaissance changed the course of civilization. And they are at the cutting edge of science, as experimental evidence stacks up to provide objective demonstration of their effectiveness.

Along with the case histories accumulating from pioneers in this new medicine and new psychology, scientists are discovering the precise pathways by which changes in human consciousness produce changes in human bodies. As we think our thoughts and feel our feelings, our bodies respond with a complex array of shifts. Each thought or feeling unleashes a particular cascade of biochemicals in our organs. Each experience triggers genetic changes in our cells.

The Dance of Genes and Neurons

These new discoveries have revolutionary implications for health and healing. Psychologist Ernest Rossi begins his authoritative text The Psychobiology of Gene Expression with a challenge: “Are these to remain abstract facts safely sequestered in academic textbooks, or can we take these facts into the mainstream of human affairs?”1

The Genie in Your Genes takes up Rossi’s challenge, believing that it is essential that this exciting genetic research progress beyond laboratories and scientific conferences and find practical applications in a world in which many people suffer unnecessarily. Rossi explores “how our subjective states of mind, consciously motivated behavior, and our perception of free will can modulate gene expression to optimize health.”2 Nobel Prize–winner Eric Kandel, MD, believes that in future treatments, “Social influences will be biologically incorporated in the altered expressions of specific genes in specific nerve cells of specific areas of the brain.”3 Brain researchers Gerd Kempermann and Frederick Gage of Salk Laboratories envision a future in which the regeneration of damaged neural networks is a cornerstone of medical treatment, and doctors’ prescriptions include “modulations of environmental or cognitive stimuli” and “alterations of physical activity.”4 In other words, when the doctor of the future tears a page off her prescription pad and hands it to a patient, the prescription might well be—instead of, or in addition to, a drug—a particular therapeutic belief or thought, a positive feeling, a gene-enhancing physical exercise, an act of altruism, a day of gratitude, or membership in a social club. Research is revealing that these activities, thoughts, and feelings have profound healing and regenerative effects on our bodies, and we’re now figuring out how to use them therapeutically.

The Dogma of Genetic Determinism

This picture of a genetic makeup that fluctuates by the hour and minute is at odds with the picture ingrained in the public mind: that genes determine everything from our physical characteristics to our behavior. Even many scientists still speak from the assumption that our genes form an immutable blueprint that our cells must forever follow. In her book The Private Life of the Brain, British research scientist and Oxford don Susan Greenfield says, “the reductionist genetic train of thought fuels the currently highly fashionable concept of a gene for this or that.”5

Niles Eldredge, in his book Why We Do It, says, “genes have been the dominant metaphor underlying explanations of all manner of human behavior, from the most basic and animalistic, like sex, up to and including such esoterica as the practice of religion, the enjoyment of music, and the codification of laws and moral strictures.… The media are besotted with genes…genes have for over half a century easily eclipsed the outside natural world as the primary driving force of evolution in the minds of many evolutionary biologists.”6

Medical schools have had the doctrine of genetic determinism embedded in their teaching for decades. The newsletter for the students at the Health Science campus of the University of Southern California proclaims, “Research has shown that 1 in 40 Ashkenazi women has defects in two genes that cause familial breast/ovarian cancer....”7 The Los Angeles Times, August 11, 2007, tells us that “Researchers have identified two mutant forms of a single gene that are responsible for 99% of all cases of a common form of glaucoma.”8 Making a single gene responsible for a disease gives journalists and scientists a simple and satisfying explanation.

Such explanations abound. On National Public Radio on October 28th, 2005, an announcer declared: “Scientists today announced they have found a gene for dyslexia. It’s a gene on chromosome six called DCDC2.” The New York Times ran a similar story the following day, under the headline, “Findings Support That [Dyslexia] Disorder Is Genetic.” Other media picked up the story, and the legend of the primacy of DNA was reinforced.

There’s only one problem with the legend: it’s not true.

There’s a second major problem with the legend: It locates the ultimate power over our health and well-being in the untouchable realm of molecular structure, rather than any place we can control, such as our lifestyle, thoughts, and emotions. In her book The DNA Mystique, Dorothy Nelkin states, “In a diverse array of popular sources, the gene has become a supergene, an almost supernatural entity that has the power to define identity, determine human affairs, dictate human relationships, and explain social problems. In this construct, human beings in all their complexity are seen as products of a molecular text…the secular equivalent of a soul—the immortal site of the true self and determiner of fate.”9

In reality, genes contribute to our characteristics but do not determine them. Blair Justice, PhD, in his book Who Gets Sick, observes that “genes account for about 35% of longevity, while lifestyles, diet, and other environmental factors, including support systems, are the major reasons people live longer.”10 The percentage by which genetic predisposition affects various conditions varies, but it is rarely 100%. The tools of our consciousness—including our beliefs, prayers, thoughts, intentions, and faith—often correlate much more strongly with our health, longevity, and happiness than our genes do. Larry Dossey, MD, observes, “Several studies show that what one thinks about one’s health is one of the most accurate predictors of longevity ever discovered.”11 Studies show that a committed spiritual practice and faith can add many years to our lives, regardless of our genetic mix.12

How did the dogma that DNA holds the blueprint for development become so firmly enshrined? In his entertaining book Born That Way, medical researcher William Wright gives a detailed history of the rise to supremacy of the idea that genes contain the codes that control life—that we are who we are, and we do what we do, because we were simply “born that way.”13 We often hear phrases like “She’s a natural born athlete,” or “He’s a born loser,” or “She has good genes,” to explain some aspect of a person’s behavior. The idea of genetic disposition has moved far beyond the laboratory to become deeply entrenched in our popular culture.

Lee Dugatkin, professor of biology at the University of Louisville, points out that after the basic rules governing the inheritance of characteristics across generations were made by Mendel, and the structure of the DNA molecule was discovered, scientists became convinced that the gene was the “means by which traits could be transmitted across generations. We see this trend continuing today in research labs throughout the world as well as in the media in reports of genes for schizophrenia, genes for homosexuality, genes for alcoholism, and so on. Genes for this, genes for that.”14 Researcher Carl Ratner, PhD, of Humboldt State University, draws the following analogy: “Genes may directly determine simple physical characteristics such as eye color. However, they do not directly determine psychological phenomena. In the latter case, genes produce a potentiating substratum rather than particular phenomena. The substratum is like a petri dish which forms a conducive environment in which bacteria can grow, however, it does not produce bacteria.”15

Since the 1970s, researchers have been turning up findings that are at odds with the prevailing mindset. They have accumulated an increasing number of findings that behaviors aren’t just transmitted genetically across generations; they may be newly developed by many individuals during a single generation. While the process of genetic evolution can take thousands of years, as genes throw off mutations that are sometimes successful, and often not, evolution through experience and imitation can occur within minutes—and then be passed on to the next generation.

The DNA spiral has become a defining icon of our civilization

Edward O. Wilson, the father of sociobiology, hinted at the very end of the twenty-fifth anniversary edition of his tremendously influential book, Sociobiology, that, in future research, “Learning and creativeness will be defined as the alteration of specific portions of the cognitive machinery regulated by input from the emotive centers. Having cannibalized psychology, the new neurobiology will yield an enduring set of first principles for sociology.… We are compelled to drive toward total knowledge, right down to the levels of the neuron and gene.”16 The notion that the genes in the neurons of our brain can be activated by input from our emotive centers is a big new idea, and indicates a degree of interconnection and feedback at odds with the straight-line, cause-and-effect model of genetic causation.

As well as beings of matter, we are beings of energy. Electromagnetism pervades biology, and there is an electromagnetic component to every biological process. While biology has been largely content with chemical explanations of how and why cells work, there are many tantalizing preliminary research findings that show that electromagnetic shifts accompany virtually every biological process. The energy flowing in, around, and out of neurons and genes interacts constantly with the outside environment. Genes are how organisms store information, while energy is about how they communicate information. Researching genes without looking at the energy component of DNA is like studying a computer hard drive without plugging in the power cable. Hard drives are composed of thousands of sectors, substructures that store information.17 You can develop impressive theories about why the storage device is constructed the way it is, and the interesting way in which the sectors are arranged, but until you plug the hard drive in and watch it functioning in the context of the energy flow that animates it, and the other components of the computer ecosystem in which it’s nested, you understand only structure and not function.

The idea that genes are the repositories of our characteristics is also known as the Central Dogma. The Central Dogma was propounded by the co-discoverer of the double helix structure of DNA, Sir Francis Crick. He first used the term in a 1953 speech, and restated it in a paper in the journal Nature, entitled “Central Dogma of Molecular Biology.”18 It has been so influential that data contradicting the central dogma have often been dismissed as mere anomalies, since they require much more complex interactions than genetic determinism can explain.19

One of many problems with the dogma, for instance, is that the number of genes in the human chromosome is insufficient to carry all the information required to create and run a human body. It isn’t even a big enough number to code for the structure (let alone function) of one complex organ like the brain. It also is too small a number to account for the huge quantity of neural connections in our bodies.20 Two eminent professors express it this way: “Remembering that the information in the human genome has to cover the development of all other bodily structures as well as the brain, this is not a fraction of the information required to structure in detail any significant brain modules, let alone for the structuring of the brain as a whole.”21

The Human Genome Project was initially focused on cataloging all the genes of the human body. At the beginning of the 1990s, the original researchers expected to find at least 120,000 genes, because that’s the minimum they projected it would take to code all the characteristics of an organism as complex as a human being. Our bodies manufacture about 100,000 proteins, the building blocks of cells. All of those 100,000 building blocks must be assembled with precise coordination in order to support life. The working hypothesis at the start of the Human Genome Project was that there would be a gene that provided the blueprint to manufacture each of those 100,000 proteins, plus another 20,000 or so regulatory genes whose function was to orchestrate the complex dance of protein assembly.

The further the project progressed, the smaller the estimates of the number of genes became. When the project finished its catalog, they had mapped the human genome as consisting of just 23,688 genes. The huge symphony orchestra of genes they had expected to find had shrunk to the size of a string quartet. The questions that this small number of genes give rise to are these: If all the information required to construct and maintain a human being—or even one big instrument, such as the brain—is not contained in the genes, where does it come from? And who is conducting the whole complex dance of assembly of multiple organ systems? The focus of research has thus shifted from cataloging the genes themselves to figuring out how they work in the context of an organism that is in “a state of systemic cooperation [where] every part knows what every other part is doing; every atom, molecule, cell, and tissue is able to participate in an intended action.”22

The lack of enough information in the genes to construct and manage a body is just one of the weaknesses of the Central Dogma. Another is that genes can be activated and deactivated by the environment inside the body and outside of it. Scientists are learning more about the process that turns genes on and off, and what factors influence their activation. We may have lots of information on our hard drives, but at a given time we will be utilizing only part of it. And we may be changing the data as well, like revising an email before we send it to a friend. One of the factors that affect which genes are active is our experience, a fact completely incompatible with the doctrine of genetic determinism.

Yet our experiences themselves are just part of the picture. We take facts and experiences and then assign meaning to them. What meaning we assign, mentally, emotionally, and spiritually, is often as important to genetic activation as the facts themselves. We are discovering that our genes dance with our awareness. Thoughts and feelings turn sets of genes on and off in complex relationships. Science is discovering that while we may have a fixed set of genes in our chromosomes, which of those genes is active has a great deal to do with our subjective experiences, and how we process them.

Our emotions and behavior shape our brains as they stimulate the formation of neural pathways that either reinforce old patterns or initiate new ones. Like widening a road as traffic increases, when we think an increased flow of thoughts on a topic, or practice an increased quantity of an action, the number of neurons our bodies require to route the information increases. In just the way our muscles bulk up with increased exercise, the size of our neural bundles increases when those pathways are increasingly used. So the thoughts we think, the quality of our consciousness, increase the flow of information along certain neural pathways. According to Ernest Rossi, “we could say that meaning is continually modulated by the complex, dynamic field of messenger molecules that continually replay, reframe, and resynthesize neuronal networks in ever-changing patterns.”23 In the succinct words of another medical pioneer, “Beliefs become biology”—in our hormonal, neural, genetic, and electromagnetic systems, plus all the complex interactions between them.24

The Inner and Outer Environment

Memory, learning, stress, and healing are all affected by classes of genes that are turned on or off in temporal cycles that range from one second to many hours. The environment that activates genes includes both the inner environment—the emotional, biochemical, mental, energetic, and spiritual landscape of the individual—and the outer environment. The outer environment includes the social network and ecological systems in which the individual lives. Food, toxins, social rituals, predators, and sexual cues are examples of outer environmental influences that affect gene expression. Researchers estimate that “approximately 90% of all genes are engaged…in cooperation with signals from the environment.”25

Our genes are being affected every day by the environment of our thoughts and feelings, as surely as they are being affected by the environment of our families, homes, parks, markets, churches, and offices. Your system may be flooded with adrenaline because a mugger is running toward you with a knife. It may also be flooded with adrenaline because of a stressful change at work. And it may be flooded with adrenaline in the absence of any concrete stimulus other than the thoughts you’re having about the week ahead—a week that hasn’t happened yet, and may never happen. Let’s take a look at the evolutionary purpose of these physiological events, and whether they’re adaptive (helpful to your body) or maladaptive (harmful to your body).

Scenario One: Ten thousand years ago, when a mugger (or a member of a hostile tribe) ran at you with a sharp blade, you quickly took action. Your blood flowed away from your digestive tract toward your muscles. Your brain became hyperactive and your reproductive drive shut down. Thousands of biochemical changes took place in all the cells of your body within a couple of seconds, enabling you to run away from the attacker, or defend yourself.

You were already one of a select group of humans who had survived the dangers of a hostile world long enough to breed. Over tens of thousands of years, those with quick responses had survived long enough to produce offspring, and those with slow responses died before they could breed. So by the time a hostile tribesman ran at you with a blade, those thousands of years of evolutionary weeding had already produced a human admirably suited to fight or flee. The changes that occurred in your body in response to a threat were adaptive; they were useful adaptations for survival.

Scenario Two: Fast-forward ten thousand years. You’re in a meeting that includes all the employees of your company. The firm has just been bought by a competitor. You know that the new owner is going to consolidate the work force. They aren’t going to need everybody.

The manager of your division announces that after the meeting, when you return to your desk, you’ll find either a pink slip, indicating that you’re terminated, or nothing at all, meaning that you’ve survived the purge. Those who find pink slips are instructed to clear out their desks immediately and report to personnel for a severance check.

Suddenly, there are two tribes in the room: those that will survive, and those that will not. Worse, nobody but the manager knows who’s in what tribe. The stress level in the room is unbearable. Who is your enemy? Who is your ally? You have no idea. You walk back to your desk, dreading what you will see, and dreading the lineup of fired and retained employees you will witness in the next hour.

Your desk has no pink slip. Neither does that of Harry, who works across from you. Suddenly, you realize that the downsizing means you’ll be thrown cheek to jowl with Harry who, though another survivor, is an incompetent liar. You look across to Helen’s desk, and you see a pink slip. Helen is the most talented person in the building, someone on whom you’ve secretly depended for your success. Because her verbal skills are poor, the management failed to realize that she’s indispensable. You realize your job has just become a lot worse, yet you will cling to it like a Titanic survivor gripping the last life jacket.

You’ve been working sixty-hour weeks for the last six months, suspecting that this Damocles’ sword will eventually fall. Your body has been ready for fight or flight for all that time, not knowing what your fate will be. The employment market is tight; you know that many of the employees fired today will have to take Draconian pay cuts in menial new jobs.

Even before the current crisis, your body was in fight-or-flight mode as you climbed the corporate ladder. Today, it’s on high alert. Your mouth is dry. You’re so tense you could put your fist through the wall. You can’t wait to get out of the office and have a few beers to unwind. Yet you know that tomorrow you’ll be back at your desk—and now you’ll have a huge new portion of the work that management has reassigned from the fired employees.

Scenario Three: It’s Sunday evening. You’ve had a good weekend. You unwound by griping to your spouse on Friday night, then by playing baseball with your kids in the park on Saturday morning. You went to a movie, a comedy, with another couple on Saturday night and enjoyed a lot of laughs. You had sex with your partner after you got home. Church was good on Sunday morning, and you saw all your old friends there and had a chance to socialize.

You’re sitting on the porch with a beer, and you suddenly realize you’re going to have to go back into that hellhole of a job in just a few hours. Your stomach knots. Your jaw clenches. You crush the beer can. You start thinking of the injustices of the previous week, wondering how you escaped the axe. Didn’t management see the glaring errors in your performance? You grind your teeth as you think of the injustice of them firing Helen, after she’s kept the whole division going, in her quiet way, for years. What ingratitude! What blindness! What ineptitude! How did those morons get to be managers in the first place?

Can you escape? No chance, the money’s good, the pension plan’s good, and no other job has comparable medical benefits—vision and dental too, plus it covers the kids, for heaven’s sake! Do you want to be pounding the pavement looking for a job like Helen will be doing tomorrow? God forbid!

Scenario Two and Three are—in terms of what you’re doing to your body—maladaptive responses. “Maladaptive” means that they aren’t helping you; they’re responses to stress that are hurtful to you. All the stress hormones are flowing, just as they were in Scenario One, but they’re doing your body no practical good. No promotion will come as a result of you overloading your system with cortisol, one of the primary stress hormones. You won’t feel better after being high on adrenaline and norepinephrine, two others.

What will happen, though, is that the circulation of these stress hormones through your system on a regular basis will compromise your immune system, weaken your organs, and age you prematurely. You’re activating genes that worked perfectly well for the caveman in Scenario One, but are counterproductive to the modern person in Scenarios Two and Three. Herbert Benson, MD, president of Harvard Medical School’s Mind-Body Medical Institute, says, “The stressful thoughts that lead to the secretion of stress-related norepinephrine impede our evolutionary-derived natural healing capacities. These thoughts are often only in our minds, not a reality.”26 According to another report, “Bruce McEwen, PhD, director of the neuroendocrinology lab at Rockefeller University in New York, says [such stress] wears down the brain, leading to cell atrophy and memory loss. It also raises blood pressure and blood sugar, hardening arteries and leading to heart disease.”27

So while the fight-or-flight response may have been adaptive ten thousand years ago, with Mother Nature cheering you on, today it’s often maladaptive, and Mother Nature is saying, “Stop! You’re ruining your body!” The trouble is that major evolutionary changes take a long time—sometimes thousands of years—and modern humans are having difficulty making adaptations in the short space of a single lifetime. We try to change our stress-addicted patterns in various ways. But the counteracting experiences we attempt—attending a four-evening stress clinic at the local hospital, a self-improvement workshop at a personal growth center, a weekend retreat at a church camp, or sitting in a Zen monastery for a few days—are like a tissue in a hurricane when compared to the evolutionary forces hardwired into our physiology.

Biochemically speaking, your body cannot tell the difference between the injection of chemicals that is triggered by an objective threat—the tribesman running at you with a spear—and a subjective threat—your resentment toward management. The biochemical and genetic effects, as far as your body is concerned, are the same. Your body can’t tell that one experience is a physical reality, and the other is a replay of an abstract mental idea. Both are creating a chemical environment around your cells that is full of signals to your genes, several classes of which activate the proteins associated with stress. A researcher observes: “Our body doesn’t make a moral judgment about our feelings; it just responds accordingly.”28

The understanding that much of our genetic activity is affected by factors outside the cell is a radical reversal of the dogma of genetic determinism, which held for half a century that who we are and what we do is governed by our genes. Research is illuminating a new biology in which consciousness plays a primary role.

Recent studies performed by Ronald Glaser, of the Ohio State University College of Medicine, and psychologist Janice Kiecolt-Glaser investigated the effect that stress associated with marital strife has on the healing of wounds, a significant marker of genetic activation. The researchers created small suction blisters on the skin of married test subjects, after which each couple was instructed to have a neutral discussion for half an hour. For the next three weeks, the researchers then monitored the production of three of the proteins that our bodies produce in association with wound healing.

They then instructed the same couples to discuss a topic on which they disagreed. Research staff was present during both the neutral discussion and the disagreement.

The researchers found that the expression of these healing-linked proteins was depressed in those couples who had a fight. Even those couples who had a simple discussion of a disagreement, rather than a full-fledged verbal battle, showed slower healing of their wounds. But in couples who had severe disagreements, laced with put-downs, sarcasm, and criticism, wound healing was slowed by some 40%. They also produced smaller quantities of the three proteins. “‘These are minor wounds and brief, restrained encounters. Real-life marital conflict probably has a worse impact,’ Kiecolt-Glaser adds. ‘Such stress before surgery matters greatly,’ she says, and the effect could apply to healing from any injury. In earlier studies done by Kiecolt-Glaser, hostile couples were most likely to show signs of poorer immune function after their discussions in the lab. Over the next few months, they also developed more respiratory infections than supportive spouses,”29 and similar studies show worse blood pressure readings,30 and increased stress hormone production31 as, “throughout the body’s entire somatic network, emotions are triggering hormonal and genetic responses.”32 The genetic effects from such environmental experiences can, in some cases, make the difference between life and death. Pharmacologist Constance Grauds, RPh, in her book The Energy Prescription, says, “An undisciplined mind leaks vital energy in a continuous stream of thoughts, worries, and skewed perceptions, many of which trigger disturbing emotions and degenerative chemical processes in the body.”33

Over two thousand years ago, the Buddha declared: “We are formed and molded by our thoughts. Those whose minds are shaped by selfless thoughts give joy when they speak or act.” Today’s research is reinforcing what wise students of the human condition have known for millennia. Neuroscientist Candace Pert, PhD, tells us that “the molecules of our emotions share intimate connections with, and are indeed inseparable from, our physiology…. Consciously, or more frequently, unconsciously, we choose how we feel at every single moment.” Practices for well-being once prescribed only by sages and priests are now being advocated by geneticists and neurobiologists.

In the tales of the Arabian Nights, when Aladdin rubbed the magic lamp, the genie appeared and granted him three wishes. In the story, once he makes his wishes, the magic vanishes. He had to think long and hard on what to choose for his three wishes.

In the real world, given the lamp of our understanding and the genie in our genes, we have an unlimited supply of wishes. Whatever wishes we put into the lamp manifest genetically. If we fill our lamps with healing words, our genes rush to fulfill our wishes—within seconds. If, like the couples in the wound study, we fill our lamps with poison, we damage the ability of our inbred genetic servants to heal us. Whereas the mechanisms driving these changes have been mysterious to the world of allopathic medicine (the conventional system of treating symptoms with concrete agents, like drugs, to produce an opposing effect), the healthy outcomes of energy therapies are beyond dispute. In the coming pages, we will look, in detail, at the precise genetic and electromagnetic mechanisms that make such healing magic not only possible, but also scientifically predictable.

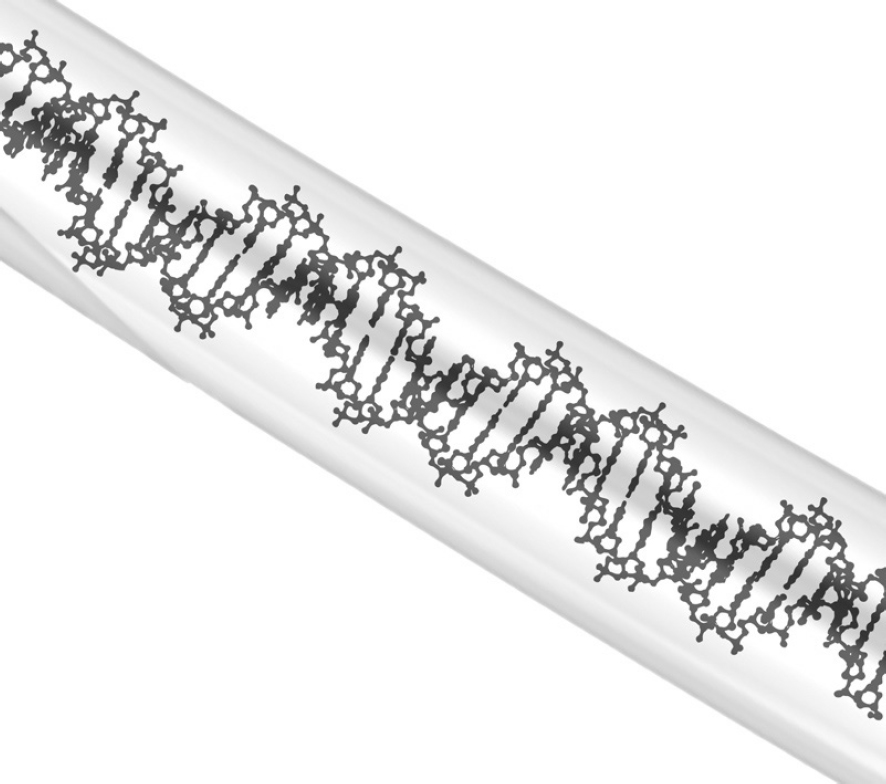

The process by which a gene produces a result in the body is well mapped. Signals pass through the membrane of each cell and travel to the cell’s nucleus. There, they enter the chromosome and activate a particular strand of DNA.

Around each strand of DNA is a protein “sleeve.” This sleeve serves as a barrier between the information contained in the DNA strand and the rest of the intracellular environment. In order for the blueprint in the DNA to be “read,” the sleeve must be unwrapped. Unless it is unwrapped, the DNA strand cannot be “read,” nor can the information it contains be acted upon. Until the information is unwrapped, the blueprint in the DNA lies dormant. That blueprint is required by the cell to construct other proteins that regulate virtually every aspect of life.

DNA blueprint in protein sheath

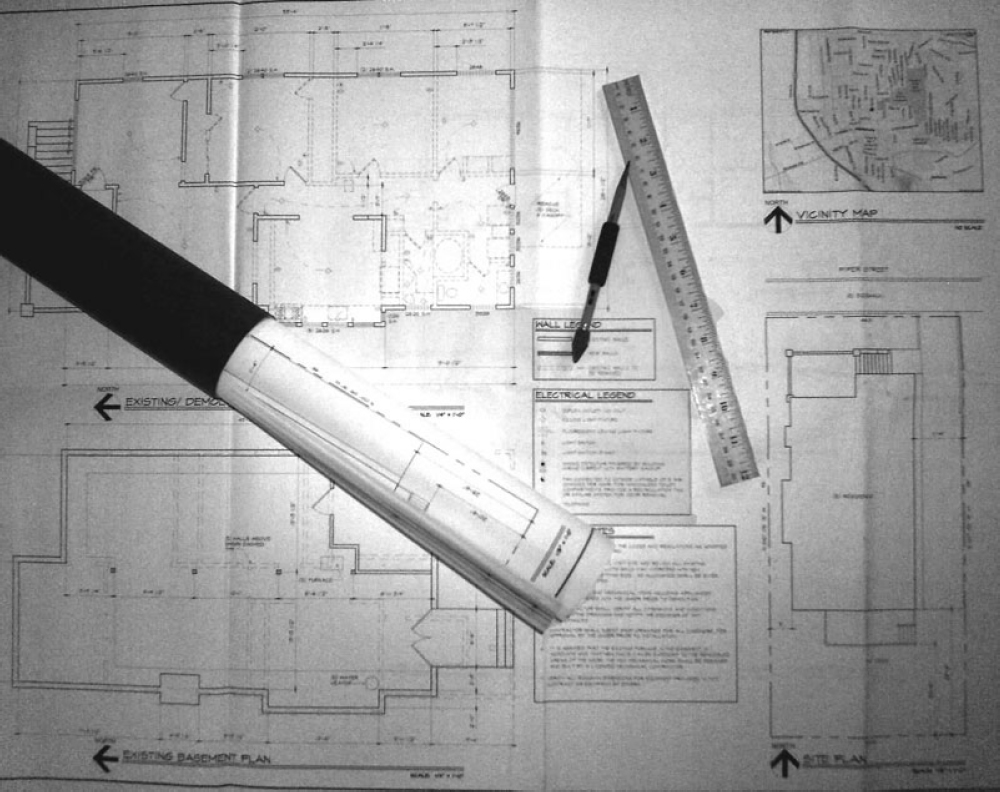

When a signal arrives, the protein sleeve around the DNA unwraps and, with the assistance of RNA, the DNA molecule then replicates an intermediate template molecule. The blueprint that has up to this point been concealed within the sleeve can now be acted upon. This is what scientists mean when they say that a gene expresses. The genetic information contained in the chromosome has gone from being a dormant blueprint into active expression, where it creates other actions within the cell by constructing, assembling, or altering products. The DNA blueprint that has up to this point been inert, concealed within the sleeve, is now revealed, providing the basis for cellular construction. Just as an architect’s blueprint contains the information to build a building, the chromosomes contain the blueprints to construct aggregations of molecules. Until the architect’s blueprint has been removed from its sheath, unrolled, laid flat on the builder’s table, and used to guide construction, it is simply dormant potential. In the same way, the blueprints in our genes are dormant potential until the genes express and are used to guide the construction of the proteins that carry out the constructive tasks of life.

Architectural blueprint and cardboard tube

Proteins are the building blocks used by our bodies for every function they perform. Proteins control the responses of our immune systems, form the scaffolding that supports the structure of each cell, provide the enzymes that catalyze chemical reactions, and convey information between cells, among many other functions. If DNA is the blueprint, then RNA comprises the working drawings required for construction and proteins are the materials used in construction. Molecules are assembled into coherent protein structures by the instructions in our DNA. That structure determines not only our anatomy—the physical form of our bodies; it also drives our physiology—the complex dance of cellular interactions that differentiate a live human being from a dead one. A corpse has anatomy, but no physiology. Proteins are used in every step of our physiology; the word “protein” itself is derived from the Greek word protas, meaning “of primary importance.”

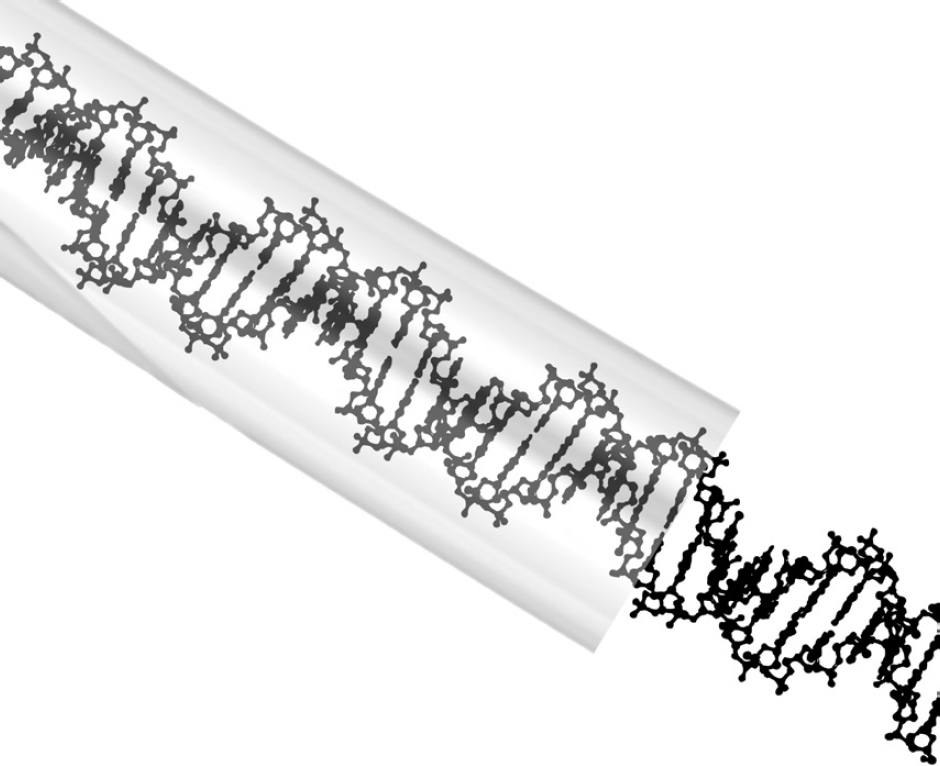

Protein sheath opens to permit gene expression

Even the simple DNA > RNA > Protein formula has recently been upset by the discovery that there are many more varieties of RNA than previously believed, and that some play a powerful role in regulating genes, rather than being simple carrier molecules. One, called XIST, has the ability to suppress an entire chromosome, the second X chromosome in females. Some single micro RNAs regulate the production of hundreds of proteins, and there may be over 37,000 micro RNAs, more than the number of genes.34 So the simple molecular picture described by Sir Francis Crick turns out to be vastly more complex than initially believed.

This whole chain of events starts with a signal. The signal is delivered through the cell membrane to the protein sleeve, which then unwraps in order to let the information in the gene move from potential (like an unbuilt building) to expression (like a finished skyscraper). And while scientists have mapped each part of the process of gene expression and protein assembly, comparatively little attention has been paid to the signals, the source of initiation for the whole process. Ignorance of the signal required to take the blueprint out of the tube is what has allowed several generations of biologists to assume that all you needed to start construction was the blueprint, which gave rise to the doctrine of genetic determinism.

Stem cells are undifferentiated cells, “blanks” that the body can make into muscle, bone, skin, or any other type of cell. Like a piece of putty, they can be formed into whatever kind of cell the body needs. When you cut your hand and your body needs to repair the break in the skin, the trauma sends a signal to the genes associated with wound healing. These genes express, stimulating stem cells to turn themselves into healthy, fully functional skin cells. The signal results in the putty being formed into a useful shape. Such processes are occurring all over our bodies, all the time: “Healing via gene expression is documented in stem cells in the brain (including the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and hypothalamus, muscle, skin, intestinal epithelium, bone marrow, liver, and heart.”35

When there is interference with this signal, which in the wound healing studies comes from the emotional states of angry subjects, the stem cells don’t get the message clearly. Not enough putty is turned into useful shapes, or the process of molding the putty takes a long time, because the body’s energy is instead being sucked away to build the threat-response biochemicals triggered by the angry emotion. Wound healing is compromised.

Notice that these signals do not come from the DNA; they come from outside the cell. The signals tell the proteins surrounding the DNA strands to unwrap and allow healing to begin. In the prestigious journal Science, researcher Elizabeth Pennisi writes, “Gene expression is not determined solely by the DNA code itself but by an assortment of proteins and, sometimes, RNAs that tell the genes when and where to turn on or off. Such epigenetic phenomena orchestrate the many changes through which a single fertilized egg cell turns into a complex organism. And throughout life, they enable cells to respond to environmental signals conveyed by hormones, growth factors, and other regulatory molecules without having to alter the DNA itself.”36

The word that Dr. Pennisi uses here, epigenetics, is new to our lexicon. The spellchecker I am using in a 2004 version of Microsoft Word does not recognize it. The issue of Science from which her quote is taken was a special issue in 2001 devoted to the new science of epigenetics. Epigenetics, referred to by Science as “the study of heritable changes in gene function that occur without a change in the DNA sequence,”37 examines the sources that control gene expression from outside the DNA. It’s a study of the signals that turn genes on and off. Some of those signals are chemical, others are electromagnetic. Some come from the environment inside the body, whereas others are the body’s response to signals from the environment that surrounds the body.

Although studying the static structure of the hard drive gives us lots of useful information, the signals that activate different sectors of the hard drive turn that information into a running program. My hard drive contains Microsoft Word, even when it’s turned off. But I have to boot up the computer (energy) and then click on the Word icon (a signal) before it becomes active. Epigenetics looks at the sources that activate gene expression or suppression, and at the energy flows that modulate the process. It traces the signals that tell the genes what to do and when to do it, and looks for the forces from outside the cell that orchestrate the whole. Epigenetics studies the environment, such as the signals that initiate stem cell differentiation and wound healing.

The activation of genes is intimately connected with healing and immune system function. In the studies of wound healing and marital conflict outlined previously, you can see a clear link between the consciousness of the participants in the study and the creation of proteins (coded by gene activation) required to promote wound healing and stem cell conversion in their bodies. The healthy mental states of functional couples signaled their bodies to turn on the expression of the genes involved in immune system health and physical wound healing. Such epigenetic signals suggest a whole new avenue for catalyzing wellness in our bodies.

When a revolutionary new technique or therapy is described, it can take a while for science to catch up. Funding must be obtained to conduct studies. Studies must be designed and approved to test the new technique. Then data are collected, and papers are written. Those papers are reviewed by committees of the researchers’ peers, and published. The ideas are then critiqued by others, refined, and replicated. This process takes years, and often decades. Much of the medical progress in the last fifty years has resulted from studies that built upon studies, from step-by-step incremental experimentation, with each step extending the reach of our knowledge a little bit further.

This evolutionary progress over the lifetimes of the last few generations has encouraged us to think that this is the way that science progresses. Yes, it is a way—but it is not the only way. There are scores of important medical procedures that were discovered years, or decades, or even centuries, before the experimental confirmation arrived to demonstrate the principles behind the treatment. Larry Dossey, in his book Healing Beyond the Body, urges us, “Consider many therapies that are now commonplace, such as the use of aspirin, quinine, colchicine, and penicillin. For a long time we knew that they worked before we knew how.… This should alarm no one who has even a meager understanding of how medicine has progressed through the ages.”38 In The Cosmic Clocks, Michael Gaugelin observes, “The scientist knows that in the history of ideas magic always precedes science, that the intuition of phenomena anticipates their objective knowledge.”39

The incremental approach to experimentation, with each study advancing the frontier of knowledge a little further, has served medicine well in areas such as surgery. But the incremental approach has broken down when it comes to many of the pressing afflictions rampant in our society, such as depression, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, posttraumatic stress disorder, and autoimmune diseases. Cancer rates, when adjusted for age, have barely budged in fifty years.40 Surgical procedures to excise cancer tumors have improved, radiation has been refined, and drug cocktails have been created, but these are variations on old themes. Much of our medical system is set up to perform heroic measures on people who are very near death, slightly delaying the inevitable at enormous cost. Ralph Snyderman, eminent physician and researcher at Duke University, sums it up with these words: “Most of our nation’s investment in health is wasted on an irrational, uncoordinated, and inefficient system that spends more than two-thirds of each dollar treating largely irreversible chronic diseases.”41

Total health spending in the United States is over two trillion dollars a year; the amount spent on all alternative therapies is estimated at just two-tenths of 1% of that figure.42 For every naturopath or licensed acupuncturist in the United States, there are seventy allopathic physicians,43 even though the treatments of the former can work where mainstream medicine fails,44 are believed effective by over 74% of the population,45 and can certainly be successful in supplementing conventional therapies.46 They also often work better than mainstream medicine for many of the predominant diseases of postindustrial cultures, such as autoimmune conditions and cancer.47 Epigenetics gives us tools to understand why our health can be affected by so many different healing modalities, and how we can learn to create an environment that supports our own healing, whichever modality we choose.

We may be comfortable with incremental exploration, yet many changes are sudden rather than incremental. The expansion of a balloon as air is injected is smooth and incremental. A balloon popping is sudden and discontinuous. Water heated in a kettle shows little change. Then, suddenly and discontinuously, it bursts into a boil. This is the kind of breakthrough of which we find ourselves on the verge. Like the first bubbles appearing in the bottom of a pan, the possibilities of epigenetic medicine, combining integrative medicine with the breakthroughs of the new psychology, are popping through the most fundamental assumptions of our current model.

We are starting, as a society, to notice the provocative research showing the effects our thoughts and emotions have on our genes. “Science goes where you imagine it,”48 says one researcher, and leading-edge therapies are now imagining science going in the direction of some of the powerful, safe, and effective new therapies that are emerging. Hundreds of thousands of people are dying each year, and millions more are suffering, from conditions that might be alleviated by epigenetic medicine. This book is an attempt to present this new science in a user-friendly manner that connects with everyday experience, and to explore the potential it holds for creating massive health and social changes in our civilization in a very short time.