Getting Started

Depending on distance, a sprint can have up to three distinct phases. The first phase is called acceleration. During the acceleration phase, we are starting to build up speed. The second phase is maximum velocity. In this phase of the sprint, we achieve the fastest speed possible. The final phase is speed endurance, in which we attempt to maintain maximum velocity for as long as possible.

Distinguishing between phases is important because acceleration and maximum velocity sprinting have subtly different techniques. In addition, specific phases may apply to some sports but not others. For example, baseball requires players to accelerate over relatively short distances. Therefore, a baseball player rarely is able to build up enough speed to reach maximal velocity. In contrast, an athlete running the 400-meters event in track and field must progress through all three phases.

Maximum Velocity

When discussing sprinting technique, running at maximum velocity is typically addressed first. Achieving maximum velocity is always the goal, whether taking a single step or running 200 meters.

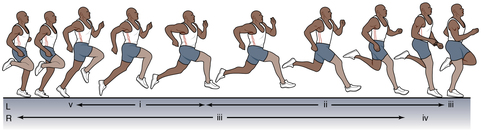

When running at maximum velocity, the foot lifts off the ground. As the foot breaks contact with the ground, it should be brought up behind your body to your hip (figure 4.1). The goal is to touch your gluteal muscles (glutes) with your heel. To understand the path of the leg and foot, picture yourself sliding your right foot up a wall behind you. From this position, swing the leg forward to the point where the thigh is roughly parallel to the ground, allowing your lower leg to unfold as you do so. From this position, drive the foot toward the ground using the hip. The ball of the foot should contact the ground slightly in front of the body. As the right foot strikes the ground, bring the left foot up toward your glutes. Pull yourself forward until your body passes over your foot and then repeat.

Adapted, by permission, from G. Schmolinsky, 2000, The East German textbook of athletics (Toronto: Sport Books).

Whenever you are sprinting, your feet and ankles should be rigid. Sometimes this position is referred to as being “cast.” When sprinting with the feet and ankles cast, the toes should not point down. One strategy to help you keep them in the correct position is to think about lifting the big toe of each foot up while sprinting.

Posture is also important when sprinting. You should stay tall when the foot strikes the ground and not allow yourself to slump forward. Staying tall maximizes your ability to exert force against the ground, whereas slumping hinders the amount of force that you can produce.

Good arm mechanics are also critical for sprinting. Your arms should be bent and held at a natural angle. Your hands can be open or closed depending on what is comfortable for you, but you should not clinch your hands into fists because this increases tension in the upper body. Additionally, the arms should move straight forward and backward; they should never cross in front of the body. Crossing the body creates rotation, which negatively affects sprinting speed (figure 4.2).

Acceleration

For a sprinter, the acceleration phase has two subphases: pure acceleration and transition. During pure acceleration, the sprinting technique is slightly different than when running at maximum velocity. During transition, the technique is almost identical to that used for maximum velocity, although the velocity is not maximal.

Pure acceleration relies on frontside mechanics, in which the leg action takes place in front of the body. When accelerating, you pick your right foot off the ground. As you do this, you lift your right knee up in front of the body. Then, using your glutes, you drive your right foot down into the ground so that you land on the ball of your foot. As you drive the right foot down, you lift the left foot, and then you continue to alternate.

Most people reach the transition phase after about 10 to 15 meters of acceleration. At this point you begin incorporating backside mechanics into the sprint, and the technique is identical to that used for maximum velocity sprinting.

When accelerating, as when sprinting at maximum velocity, you swing your arms forward and backward and maintain a good, straight body posture (although you may be leaning forward slightly as your velocity increases). Your feet and ankles should still be rigid, or cast.

Speed Endurance

Speed endurance is the ability to maintain maximum velocity. Except for track and field athletes, there’s not a lot of need to worry about speed endurance. Few sporting situations allow an athlete to run in a perfectly straight line and accelerate continuously long enough for this quality to come into play. Occasionally, however, speed endurance may be required, especially if a critical mistake or several mistakes are made. In this case, realize that the running mechanics are identical to those used for running at maximum velocity. The challenge is that maximum velocity can be maintained only for a few seconds. So at this stage we are simply trying to slow down as little as possible.

Although speed endurance is not as critical except in track and field, repeated sprint ability is essential for sports that require intermittent bursts of speed, such as soccer, lacrosse, and rugby. Integrating sprint conditioning work into the training programs for these sports can pay huge dividends on the playing field, especially during the latter stages of a competition. Players who are better conditioned are able to generate bursts of speed throughout a match. In many cases, this training allows an athlete to beat the opponent to the ball, get enough separation to make a catch, or outlast the competition in a dead heat. Speed endurance can literally be the difference between winning and losing.