How Strength and Power Are Trained

A number of tools can be used to train for strength, such as barbells, dumbbells, kettlebells, and strongman implements like stones, logs, tires, and so on. When training for strength, the focus is on multijoint exercises, heavy weights, low volume, and complete recovery between sets. Normally, when training for strength we perform three to five sets per exercise, for fewer than eight repetitions per set, with at least 80 percent of maximum weight, and allowing two to three minutes of recovery after each set.

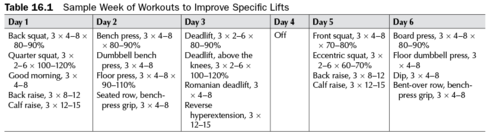

Training for strength is normally organized in one of two ways. First, it can be trained around the idea of improving specific lifts. Table 16.1 shows an example of a week of strength workouts designed to improve three standard exercises: the squat, bench press, and deadlift. Within this program, two days are focused on training the bench press and squat, and one day is geared toward the deadlift. Each of the exercises included in the workouts is meant to help enhance the lift that is being trained that day. Note: The italicized exercises are found in part II. Refer to the exercise finder for more information. Powerlifters and people who are training but not playing a sport use this kind of workout.

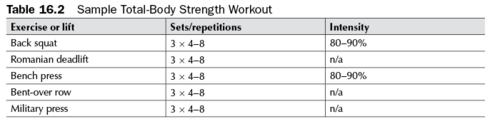

Strength can also be developed using a total-body approach to training. Table 16.2 shows a sample workout that would accomplish this. This type of workout is commonly seen in the training of athletes, and it too makes use of standard strength exercises. Almost every muscle of the body is trained in this session. This approach is used with athletes because they are attempting to improve several attributes with their training, so the amount of time devoted to any one aspect of training is limited.

Power is trained using the Olympic lifts and their variations, plyometrics, and explosive variations of free-weight exercises like jumping squats and speed squats. With power training, the focus is on correct technique and speed of movement. For that reason, fatigue is not a good thing because it tends to result in slow and sloppy training, which is counterproductive. To train for power, three to five sets of an exercise with up to six repetitions per set are typically performed. Two to three minutes of recovery after each set is normal. The amount of weight used for these types of exercises is around 50 to 70 percent of maximum.

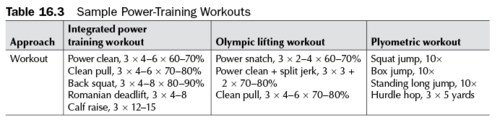

Power training can be organized in a number of ways. One way is to integrate it into a strength-training workout. When this is done, the power exercises should be performed at the beginning of the training session. They can also be used as stand-alone workouts organized by exercise type (for example, an Olympic lifting workout or a plyometric workout). Any of these approaches can be effective. Table 16.3 provides examples of the various ways to organize power training.

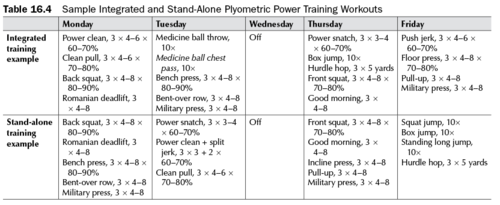

In the training of athletes, it is not unusual to see some power training in the form of Olympic lifts integrated with strength training and to see stand-alone sessions of plyometrics. It is also common to see training focused on a single quality. Table 16.4 shows examples of how both approaches could be executed using exercises commonly performed for these purposes. Both of these extreme approaches to power training are effective. Because these two physical qualities are interrelated and key to successful sport performance, athletes need to focus on both strength and power to be successful.