Defining experimental animation

Paul Taberham

To the uninitiated, experimental animation may seem willfully difficult. The artist Stuart Hilton observes that the field is aggressively uncompromising, difficult to fund, difficult to watch and difficult to explain. Yet when it is well executed, it can create ‘the right kind of wrong’ (‘Edges: An Animation Seminar’ 2016). As uncompromising as it may be, learning to appreciate experimental animation yields a world of provocative, visceral and enriching experiences. We may ask, what does one need to know when first venturing into this style of animation? What are the first principles one should understand? This chapter will outline some of the underlying assumptions that can serve as a springboard when stepping into this wider aesthetic domain.

The basic premises of experimental animation hark back to the early twentieth century avant-garde. Ad Reinhardt said the following of modern art in 1946: ‘[it] will react to you if you react to it. You get from it what you bring to it. It will meet you half way but no further. It is alive if you are.’ (Reinhardt, quoted in Bell and Gray [1946], 2013, 35).1 The same idea applies to experimental animation. The richness of one’s response will determine the value of the artwork, and so a willing and imaginative mind is a necessary precondition.

Experimental animation need not be understood as a ‘genre’ with its own set of iconographies, emotional effects or recurring themes like westerns, horrors or romantic comedies. Rather, it may be understood as a general approach with a number of underlying premises. A common assumption is that experimental animation is concerned with pushing boundaries, though within the boundary-pushing, there are norms and conventions which emerged that have been revisited and refined over time. Examples include the tendency towards evocation rather than the explicit statement of ideas; freely exposing the materials used to make the film; a staunch aesthetic and thematic individualism of the artist who produced the work; and on some occasions, the visualisation of music. All of these themes will be discussed in the course of this chapter.

Instead of offering traditional narratives like those found in the commercial realm, experimental animation typically offers formal challenges to the spectator. In commercial cinema, the spectator is ordinarily compelled to speculate on how the story will resolve, and it may invite viewers to reflect on the behaviour of the characters and themes raised by the story. The underlying question viewers must ask when engaging with an experimental animation is more likely to be how should they engage with the given material.

In the commercial realm, implicit assumptions about what determines a film’s value can go unnoticed. One may ask, what makes a movie compelling to begin with? A typical answer for mainstream filmmaking is that it needs an engaging plot, compelling characters and it should provoke an emotional investment on the part of the viewer. However, there is no all-pervading rule that says these are essential criteria a film must follow in order to provide a meaningful or valuable experience. A film might be appealing because it presents unique formal challenges, it might offer an intense visceral experience, challenge traditional standards of beauty, or it might frame a philosophical question in a provocative way. There are a variety of ways in which a film may be engaging or memorable. Thus, underlying assumptions about filmic experience are called into question when engaging with experimental animation.

A common misconception is that experimental animation, along with other artforms which directly challenge a spectator’s habits of engagement such as contemporary dance, atonal music or abstract painting, should be understood as elite, intended only for a specialised audience. Thanks to websites like Edge of Frame, the Experimental Animation Zone page on Vimeo and the websites for the NFB, the Iota Center and the Center for Visual Music, experimental animation is easy to discover and explore. It also need not be considered an elite art because of all types of film, it is the cheapest to produce – experimental animation has traditionally been created by a single artist without a team of staff members. High production values aren’t as important as original ideas, and thanks to home computers and online streaming, they can be produced and distributed inexpensively. In this sense, it is the most inclusive of all types of filmmaking.

Motivation for creating experimental film (and animation by extension) varies from artist to artist. Some think of the field as reactive, possessing an oppositional relationship to commercial filmmaking and the values of mainstream society. Malcolm Le Grice, for instance, offers a reactive model of experimental film, suggesting that its aesthetic challenges take on a political dimension by prohibiting the audience from being lulled into a passive state of reception, unlike commercial film (Le Grice 2009, 292). It serves as an antidote to the mainstream. Others endorse a parallel understanding of experimental film, in which the mainstream and avant-garde operate in different realms without influencing one another (Smith 1998, 396). Within this conception, the films may be enjoyed without the confrontational polemics sometimes implied by avant-garde filmmakers. Ultimately, the reason artists produce work in the way they do can be taken on a case-by-case basis, but both are legitimate motivations.

Those who create experimental animation may be considered first and foremost artists in a more generalised sense, for whom animation fulfils their creative needs. They might also be painters, sculptors or multimedia artists. In this instance, why might an artist turn to animation instead of live action filmmaking or other forms of expression? Creative freedoms granted to animators include the ability to manipulate motion down to the smallest detail – movement (smooth and jarring) is an aesthetic concern for experimental animators, in addition to form, colour and sound. One may also create an entire, self-contained environment without real-life actors or locations. Conversely, one may also ‘coax life’ out of physical inanimate objects through stop-motion animation. Artists who express themselves through abstraction may also extend their craft to animation, bringing movement to their non-figurative imagery.

Major figures

There are major figures of classical experimental animation who have received a notable amount of critical attention within the field. These may be divided into four broad waves. The first wave featured European abstract painters working in the silent era who turned to animation, inspired by musical analogies to imagery. These are Hans Richter (1888–1976), who broke the cinematic image into its most basic components (darkness and light) with simple motions. Viking Eggeling (1880–1925) used more elaborate shapes than Richter, which would swiftly transform in a variety of permutations. Walter Ruttmann’s (1887–1941) abstract shapes were loosely evocative of figurative imagery, with triangles jabbing at blobs of colour, waves crashing across the bottom of the screen, and the like.

The second wave continued to work with sound-image analogies, but their work was also accompanied by (and sometimes synchronised with) music. The best-known artists of this era are Oskar Fischinger (1900–1967) and Len Lye (1901–1980). Both are comparable in their use of image-sound equivalents, but Fischinger’s style was shaped by classical music, traditional cel animation and a graphic formalism. Lye’s style was looser, making use of ‘direct animation’ (scratching directly onto the celluloid) techniques and up-tempo popular music of the time. Two other noted figures who emerged around the same period are Mary Ellen Bute (1906–1983), who pioneered the use of electronic imagery in her abstract films, and Jules Engel (1909–2003), a multi-disciplinary fine artist and teacher who was the founding director of the Experimental Animation program at CalArts.

The third wave began to pull away from direct musical analogies. Norman McLaren (1914–1987) was arguably the most varied and prolific of experimental animators, owing to his long-running employment at the National Film Board in Canada. McLaren worked with a wide range of animation techniques and produced films that both harked back to previous experimental animators and also innovated new approaches. John Whitney Sr. (1917–1995) initially collaborated with his brother James, and later went on to pioneer computer animation, combining his mutual interests in abstraction, mathematics and visual harmony. Harry Smith (1923–1991) produced cryptic collage animations, and also painted abstractions directly onto film strips that were reportedly made while under the influence of hallucinogens. Jordan Belson (1926–2011) drew inspiration from meditation and spiritual practices to create abstractions that were suggestive of macro-cosmic and micro-cosmic imagery. Robert Breer (1926–2011) developed a loose, sketch-like style whose steam-of-consciousness images sit on a threshold between abstract and figurative, moving and static.2

The final wave works more consistently with referential imagery instead of abstraction, and occasionally includes spoken word. Lawrence Jordan (1934–) creates phantasmagorial evocations with the use of cut-out animation, resembling the collages of Max Ernst. Jan Švankmajer (1934–) and is a self-described surrealist (though his work began after the heyday of the surrealist movement), who uses stop-motion animation on everyday objects to unsettling effect. Stephen and Timothy Quay (known together as The Quay Brothers (1947–)) are also stop-motion artists, who were influenced by Švankmajer, amongst other Eastern European artists. Like their Czech precursor, they also create unsettling film-poems, reanimating abandoned dolls and other detritus. Their films are notably pristine, with smooth motion and delicate layers of dust and grime.

This list of prominent artists is not intended to be exhaustive, nor does it lead us up to the present. It only covers artists which have been canonised in western texts and made (for the most part) commercially available. However, it covers some of the most widely cited figures who came to prominence between the 1920s and the 1980s. In part, this is because from the vantage point of the time in which this chapter was written, the domain of experimental animation has become more difficult to define and organise into canonical figures from the 1990s onwards. This may be due to the growth of the Internet and increased freedom for artists to share their work with the public. In any case, the artists listed above serve as exemplars when first discovering experimental animation.

Single-screen animations will be the focus of this chapter, rather than multi-screen works, gallery-specific animation rather than site-specific (e.g., projecting onto the side of buildings). Nor will the recent adoption of .gif files (brief, looped digital films) as found in the work of artists like Lilli Carré and Colin MacFadyen be considered, or David O’Reilly’s recent forays into videogame development. These are exciting new developments in the field however, which deserve vigorous discussion of their own.

Previous definitions

There are two seminal books from the field of animation studies which offer their own definitions of experimental animation: Paul Wells’ Understanding Animation, and Maureen Furniss’ Art in Motion: Animation Aesthetics. Both formulate their definitions by contrasting the tendencies of commercial animation with those of experimental animation. As well as helping to identify what makes a film experimental, they also help us to understand how to engage with such works.

Wells defines commercial (or ‘orthodox’) animation as consisting of configuration (as opposed to abstraction), temporal continuity, narrative form, a singular style and an ‘invisible’ creator. He notes that the materials used to create the imagery in these kinds of animation are hidden, and they are driven by dialogue. By contrast, experimental animation tends towards the abstract over the figurative, non-continuity, creative interpretation over traditional storytelling, exposure of the materials used to make the animation, multiple styles applied in the same film, the artist who produced the work feels present and the film will be driven by music instead of dialogue. (Wells 1998, 36)

Each contrasting point (e.g., configuration – abstraction) is placed on a continuum and animations may sit between the various poles. Between orthodox and experimental animation sits “developmental” animation, which serves as a conceptual catchall for films that don’t belong in the other two categories. Wells’ typology productively indicates that there is a continuum between orthodox and experimental films. The model also usefully places animations within the commercial and independent realm on the same continuum, though they are typically kept separate. His definition of orthodox animation is satisfying, but the list of characteristics which pertain to the experimental raises as many questions as it resolves.

If the canonical artists listed above are to be taken as typical examples of experimental animators, then there are a high number of counter-examples to his characteristics of experimental animation which should be considered intrinsic to the form. For instance, abstraction in experimental animation arguably reigned supreme from the 1920s to the 1940s, but less so after that. As such, the claim that using figurative imagery pulls away from the realm of the experimental is contentious.

Wells also suggests that ‘experimental animation often combines and mixes different modes of animation’ (1998, 45). This is true of Len Lye and Robert Breer (both listed above), but it is atypical of some of the others such as Viking Eggeling, Oskar Fischinger, Jules Engel or John Whitney. It can, however, be found in commercial animation such as the combination of cel and CG in Disney’s Treasure Planet (2002, Dir. Ron Clements and John Musker), or the more recent Legend of the Boneknapper Dragon (2010, Dir. John Puglisi) in which the present is represented with 3D animation, while flashbacks switch to 2D. The Amazing World of Gumball (2011–) also combines 2D, CG and stop-motion. Mixed-media is increasingly intercepting commercial animation, so it is possible that Wells’ typology (which was first published in 1998) would need to be revised today in this respect.

Finally, Wells suggests that experimental films are motivated by dynamics of musicality rather than dialogue. He presumably has visual music artists like Len Lye and Oskar Fischinger in mind when making this claim, though musical analogies to imagery have become less relevant to the field of animation since the 1950s. One may also bear in mind the centrality of music to commercial animations during the 1930s, like Disney’s Silly Symphonies series (1929–1939). In addition, there are animations that are arguably driven by action rather than music or dialogue, such as Tom and Jerry or the Road Runner cartoons.

In essence, I suggest that abstraction, the blending of animation techniques and dynamics of musicality should not necessarily be considered intrinsic to experimental animation. Or rather, making animations figurative, using a singular animation method and not structuring your film around music do not diminish a film’s status as ‘experimental’.

Maureen Furniss’ comparable series of dichotomies separates ‘traditional/ industrial/hegemonic forms’ with ‘experimental/independent/subversive forms’. (Furniss 2008, 30) It cites several similar elements to Wells’ tabulation as being indicative of experimental animation such as that they tend to be non-narrative, abstract and non-linear. It also raises additional issues regarding the contexts in which they are created, funded, exhibited and interpreted. Furniss productively comments that experimental films are typically produced with small budgets, by individuals and they are made for small-scale exhibitions. In addition, they challenge dominant beliefs and reflect concerns of marginalised groups.

These are all useful issues to raise. What might be queried is the way in which experimental form is clustered together with independent and ‘subversive’ forms (the latter of which isn’t a term with a wide currency), since these approaches can take notably different shapes. An ‘independent film’, as it is generally understood, is more likely to directly challenge dominant beliefs and reflect concerns of a marginalised group. The canonical ‘experimental’ artists cited in this chapter are white, largely male and either American or European. In this respect, they are not marginalised unless one considers artists generally (as counter-culturalists) to be outsiders. In addition, abstract and surrealistic films need not be understood as representing the concerns of marginalised groups (such as people identifying as LGBT+, ethnic minorities or the disabled), so much as creating ‘evocations’ or film-poems.3

Both Wells and Furniss prudently make the point that these categories exist on a continuum. Furniss rightly comments that both of her categories represent extremes ‘to which few cultural products could adhere completely; but, evaluating a particular text in terms of the various paradigms, it is possible to see a given work as generally being related to one mode of production or the other’ (ibid.). This is a suitable way to think about categories such as commercial or experimental animation, since it is seldom a tidy distinction.

The role of narrative

What may be productive to add to both definitions of experimental and commercial animation is a brief consideration of what narrative is, since it is an important component that divides the commercial from the experimental. To offer a bare-bones definition, we may say that a narrative consists of a chain of events which are causally linked, that occur in a defined passage of time and space (Bordwell and Thompson 2008, 75). They also typically feature protagonists. In addition, the generic convention for commercial filmmaking and animation is that they are built around conflict and resolution, with a central protagonist who achieves a defined goal while overcoming an obstacle. These are the sorts of narratives one encounters when watching a Disney, Pixar or Dreamworks movie.

Some animations feature narratives which don’t fit that pattern. They tend to be funded via arts grants which aren’t expected to make the same amount of profit as the major studios, and sometimes do represent marginalised groups. This moderate position between the extreme poles of commercial and experimental is what would typically be defined as ‘independent’. Examples would include feature films like Persepolis (2007, Dir. Marjane Satrapi and Vincent Paronnaud), Mary and Max (2009, Dir. Adam Elliot), The Illusionist (2010, Dir. Sylvain Chomet) and It’s Such a Beautiful Day (2012, Dir. Don Hertzfeldt) though there are many more.

Like conventional narratives, independent animations normally feature discernible characters and involve a chain of events occurring in cause and effect relationship. Beyond this, they also negotiate storytelling in a different way to commercial animations; they might lack a disruption and subsequent resolution in a traditional sense, protagonists may drift instead of driving towards a defined goal, and there are no easy divisions between heroes and antagonists. Also, obstacles are not necessarily overcome in the way they are in commercial animations. These are stories that, like life itself, lack the tidiness of conventional narratives. They offer insight into the human condition, but the meaning of the film is left open for audiences to ponder.4

Experimental animation doesn’t typically feature causally linked events which occur in a defined time and space. It may be conceived as an enchantment, rather than a story. If there is a character at all, they would ordinarily be psychologically opaque. Or a human figure might appear, but it’s in the same manner as a life drawing, not to be understood as an agent with internal thoughts and intentions, but as an aesthetic object such as those featured in Ryan Larkin’s Walking (1968) or Erica Russell’s Triangle (1994).

Of course, even between these three categories (commercial, independent and experimental) there are borderline cases. David O’Reilly’s The External World (2012), for instance, features a network of recurring characters in a staged enactment. Causal links between scenes are either tenuous or non-existent and the humour is absurdist, dark and irreverent. It ‘feels’ like an experimental film, even though it features a loose narrative in a manner that is more typical of an independent film. Ultimately, categories such as commercial, independent and experimental should be used to elucidate one’s understanding of a work of art, not limit it. As such, they need only be used insofar as they are useful.

Setting parameters

With previous definitions and distinctions in mind, a series of tendencies that pertain to the field of experimental animation may be detailed. Like Wells and Furniss’ models, I hasten to add that these are not essential characteristics but rather tendencies.

First, the context of distribution and production may be outlined in the following way:

• It may be created by a single person or a small collective.

• The film will be self-financed or funded by a small grant from an arts institution, without expectation to make a profit.

• Instead of undergoing commercial distribution, experimental films are normally distributed independently online, or through film co-operatives to be exhibited by film societies, universities and galleries.

Second, the aesthetics of experimental animation may be characterised thus:

• They evoke more than they tell, and don’t offer a single unambiguous ‘message’.

• Surface detail typically plays a more significant role in the experience of the film than the content.

• The materials of animation may be consciously employed in a way that calls attention to the medium.

• Psychologically defined characters with discernible motivations and goals do not feature.

Third, the role of the artist may also be considered:

• The personal style and preoccupations of the artist will be readily discernible.

• The artist may try to express that which cannot be articulated by spoken word, such as abstract feelings or atmospheres. In a sense, they try to express the inexpressible by calling upon their non-rational intuitions.

• Instead of pre-planning a film and then executing that plan in the same manner as a commercial film, the entire act of creation may be a process of discovery.

With a working definition of experimental animation in place, some of these tendencies will be considered in closer detail.

Art as an imaging board

An experimental animator creates meaning in a different way to a traditional storyteller. In conventional stories, events can be interpreted unambiguously. For instance, in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) a young maiden is pursued by a jealous Queen. She hides with kindly Dwarfs, but the Queen tricks her into eating a poisoned apple and she falls into a death-like coma. The Queen subsequently falls off a cliff while being chased by the Dwarfs, and Snow White is revived by her true love’s first kiss. An underlying message is easy to identify: It is better to be gentle and kind than jealous and cruel.

In experimental animation, a film might defy straightforward description and not necessarily feature an explicit take-away moral or message. Experimental animators don’t express ideas in a direct way. They provoke rather than tell and in turn, the spectator is free to interpret the work as they will. The goal isn’t to unravel the hidden meaning set up by the artist, but rather respond to the experience imaginatively, as if the work was a mirror reflecting back what the spectator brings to the experience. If a viewer is concerned that they don’t ‘get it’, they may instead ask themselves how it made them feel. It might create a mood of ambient entrancement, agitation, relaxation or disorientation, for instance. This is an adequate and legitimate response. In this collection, Lilly Husbands comments on how the appeal of experimental animation is in part rooted in the way it resists straightforward interpretation:

Their indeterminacy is one of their most stimulating and productive aspects because it invites the viewer to actively participate in their comprehension of the animation. Rather than coming across as vague or confused, indeterminacy in experimental works is often what immediately piques our curiosity, urging us to discover all the various ways of understanding them.

(Husbands 2019, 190)

The critic Jonathan Rosenbaum also comments on this, highlighting the risk of looking for a straightforward answer to films that don’t offer explicit messages:

One way of removing the threat and challenge of art is reducing it to a form of problem-solving that believes in single, Eureka-style solutions. If works of art are perceived as safes to be cracked or as locks that open only to skeleton keys, their expressive powers are virtually limited to banal pronouncements of overt or covert meanings – the notion that art is supposed to say something as opposed to do something.

(Rosenbaum 2018)

One may allow the feeling of mystery, then, to be embraced and appreciated as part of the experience when engaging with experimental animation. Instead of being held captive by the film for its duration and then promptly forgetting it afterwards, a work may instead leave you with an itch, or a feeling that there was something you missed that compels you to revisit it days, weeks or years later. You might not solve the film in subsequent viewings, but may still settle into the mysteries.

Instead of thinking about experimental animation from the perspective of a viewer, one may also consider it from the perspective of the artist. During the creative process, an artist might reflect on a given subject and a series of images will come to mind. Using a form of non-rational intuition, the meaning might be highly internalised and various references won’t necessarily be discernible to the general viewer (although the title can sometimes offer a clue). Even if the spectator is not privy to whatever motivated the images, one may nonetheless understand that there was some form of rationale or reasoning behind the imagery, and that understanding informs the experience.

For example, consider Robert Breer’s Bang! (1986) which on the surface appears to feature a string of dissociated images, but there is a discernible theme to those who look for it. Broadly speaking, the film is autobiographical, and it deals with Breer’s childhood and adolescence. Instead of telling a linear story, the film is more like a daydream in which images ‘skip around the way thoughts do’. (Breer, quoted in Coté 1962/63, 17)

We see familiar fascinations of a boy growing up in the 1930s and 1940s – outdoor activities (the forest, rafting, a waterfall), sport (football and baseball), Tarzan and airplanes. We also see images evoking pubescent, burgeoning sexuality (drawings of a nude woman, a drooling man and sperm swimming) and a female voice utters ‘such a male fantasy’. Adolf Hitler also momentarily appears on the screen alongside German fighter aircrafts – Breer was 13 years old when the Second World War broke out. His early interest in vision also appears in the film, featuring optical toys such as the thaumatrope. Reference to personal regret is also made, with the words ‘don’t be smart’, ‘don’t be stupid’ and ‘don’t be crazy’ flashing across the screen, all phrases one is often told during childhood and teenage years.5

Presented with these images, the spectator is free to ruminate on themes raised in the film such as nostalgia, regret and conflict (both in war and sport). The notion of meaning in the film is distinctly internalised with Breer drawing from his own memories of youth. Yet with these sounds and images, viewers are free to either feel something, or feel nothing. Interpret it, or not. Artists accept that they create works, send them into the world and viewers will make their own readings and interpretations. As with all experimental animation, there is no single correct reaction to Bang!; indeed, the notion of a correct reading would be considered limiting. Without guidance, the theme of childhood is easily missed. Even if it passes unnoticed, the viewer may still be engaged by Breer’s distinctive range of materials used to make the film such as felt-tip pen, pencil, filmed television, photographs and childhood drawings. His use of a loose sketch style and flickering imagery is also enough to hold the viewer’s interest.

In the creation of art, an artist may enter a state of flowing free association where one must listen, and remain true to one’s muse. Some artists, such as those during the Gothic period did not consider their work to be a form of personal expression; rather, they were channelling God’s will. Today, the creative act is less commonly understood in these terms, but the notion of drawing from an exterior force (divine or otherwise) persists.

One artist who did consider his work to draw creatively from a sacred force is Jordan Belson. He drew inspiration by practicing meditation and then recreating his inner visions through film. In Allures (1961), the viewer’s attention is continually drawn back to the centre of the frame. We see distant spirals and flicker effects, and drawing together scientific and religious imagery, we also see intersecting dots resembling atomic structures and revolving mandalas.6 The soundtrack works with the imagery to create a unified experience of entrancement. An abstract work like this seems to defy interpretation altogether, so how does one talk about it? In a sense, the images may be understood and appreciated in a pre-conscious way; indeed, Belson encouraged this. He has commented that his films ‘are not meant to be explained, analysed, or understood. They are more experiential, more like listening to music’ (Belson quoted in MacDonald 2009, 77).

Nonetheless, images can be imaginatively interpreted, which may enrich one’s experience. For instance, one may say that the opening images in Allures create the impression that the spectator is being pulled through a cosmic tunnel into the imaginative space of the film, or the screen awash with light represents enlightenment. Aimee Mollaghan has suggested that in Allures, a high-pitched electronic sound accompanied by a lower beating rhythm resembles the nervous and circulatory systems. In addition, the film features ‘fields of dots and dashes super-imposed over each other [that] reflect the speed and activity of the neural pathways as they enter even deeper into the state of meditation’ (Mollaghan 2015, 89). By looking at the specifics of this wholly abstract film, it is possible to discern the theme of inner-consciousness. Conversely, Gene Youngblood suggests that the film depicts the birth of the cosmos. (Youngblood 1970, 160) Suffice to say, both interpretations of this film – that it expresses the small and large, the micro and macro, are accommodated in the work. It is possible (and rewarding) to see it both ways.

To summarise this part of the discussion, we may say that experimental animation defies straightforward description, and is poetic and suggestive instead of concrete. Artists use non-rational intuition to create images which viewers can respond to imaginatively. There is no single correct reading of an experimental animation, and the film may be designed to create a feeling which can’t be articulated through a conventional story.

Presence of the artist

Generally, commercial animations aren’t intended to be interpreted as the work of an expressive individual. In part, this is because commercial animations are highly collaborative and require a large working crew. There are exceptions such as directors Hayao Miyazaki, Pendleton Ward and Genndy Tartakovsky – auteurs whose names bring a series of themes and stylistic tropes with them, even if their work is collaborative. More broadly this is not the case, general audiences don’t tend to remember who directed Lady and the Tramp (1955, Dir. Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson and Hamilton Luske), The Lion King (1994, Dir. Rob Minkoff and Roger Allers) or Frozen (2013, Dir. Jennifer Lee and Chris Buck), to name a few examples. These studio-based films, moreover, also tend to have multiple directors.

The artist’s creative presence can be more vividly felt when watching an experimental animation. We can suppose that experimental animators will express more personal visions than commercial directors since they generally work alone, and they do not produce animations commissioned by a studio with an expectation to make a profit. In experimental animation, the artist is the creative force who ‘communicates’ (what is the film saying?) and who ‘expresses’ themselves (what is the artist’s personal style?) rather than striving to ‘entertain’ – though the film should be engaging on some level. Familiar viewers will watch films by an artist expecting certain themes and techniques the director has used previously. The film, in turn, becomes understood as a chapter in a larger oeuvre. The distinctiveness of individual voices may be in part accountable to the fact that the creation of art may often be more heavily conceived as a process of discovery, rather than a film that is pre-planned and then subsequently executed.

We have already considered how there are broad principles used to understand the field of experimental animation (they evoke more than tell, call attention to their own medium and feature an authorial presence). There are also more localised principles which apply to specific artists. Robert Breer, for instance, utilises a range of materials to create his films and images loosely relate to each other in a similar manner to a daydream; Jordan Belson works with abstract images that evoke impressions of inner-consciousness and also the larger universe.

Experimental animators are sometimes drawn to depicting extreme psychic states or madness. Jan Švankmajer for example associates himself with the surrealist art movement, in which the artist draws creatively from the unconscious, the part of the mind that remains untouched by rationality, social convention and the laws of nature, which is most readily accessed through dream. While experimental animators tend to look inwards and create something that feels internalised, as in the cases of Robert Breer and Jordan Belson cited above, they nonetheless try to create an experience that will offer a meaningful experience to others. Otherwise, there would be no reason to share it in the first place.

An artist may be unique in the way they question premises intrinsic to commercial animation. As previously stated, underlying assumptions about filmic experience are called into question – does a film need to tell a story? Does it need compelling characters or emotional investment? In addition, should animated movement always strive to be smooth? Do images need to be beautiful by conventional standards? In a comparable spirit to Jan Švankmajer, recent animators like Katie Torn and Geoffrey Lillemon express themselves with imagery that would typically be considered grotesque.

David Theobald’s authorial presence can be vividly felt in his films since they frame a philosophical question in a distinctive way. He is known for producing high quality computer generated animation, but featuring minimal onscreen movement (challenging the assumption that an animated film needs to be full of activity).

Lilly Husbands explains:

although his works might resemble the visual aesthetic of these commercial studios, Theobald’s animations spend their entirety focusing on places and objects that would appear in a Pixar animation only very briefly and most likely somewhere in the background. The intensive labour that goes into Theobald’s animations is perversely used to produce images of everyday objects and scenarios that would normally be deemed unworthy of prolonged attention.

(Husbands, 2015)

Theobald’s 3-minute Kebab World (2014) features a single, static shot that looks into a kebab takeaway shop window. Most of the frame remains motionless, though the kebab slowly rotates and the neon lights of the shop sign blink. A radio plays throughout, and the sound of a police siren briefly passes by, complete with blue and red flashing lights illuminating the contents of the frame, though we never see the car. For those attuned to Theobold’s approach, the banality of subject matter and extended lack of narrative activity may be interpreted as humorous (why would anyone take the time to animate something as dull as this?), even if it tests the limits of the viewer’s patience (see Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1 Still: Kebab World, David Theobald 2014.

Other films by the same artist operate in a similar way, such as Jingle Bells (2013) and Night Light (2016). As stated previously, Theobald’s authorial presence is readily discernible in these films because they make a philosophical statement in an aesthetically provocative way. While humans, by their very nature, conceive of their surroundings in relation to themselves, in reality the exterior world has its own nature that is independent of human thought and intention. Husbands explains: ‘Theobald’s refusal to cater to conventional narrative expectations, denying spectators their attendant gratifications, serves to remind them of the fact that everything is not always selfishly, anthropocentrically, for us’ (ibid.). The world, in other words, continues whether we are paying attention to it or not.

As briefly illustrated with Breer, Belson and Theobald, then, the creative force behind experimental animation is more vividly present than it typically is in a commercial animation.

Surface details

Outside the field of experimental animation, the surface details of the animated images are intended to be enjoyed – from Disney movies to anime action spectacles. In commercial animations, however, the function of the surface detail is always subordinated to the story that it serves, and won’t play as big a part of the experience once it has been integrated into the larger, more ‘meaningful’ form of an over-arching story. By contrast, the sensuous appeal of some experimental animations, the colours, movements and visual textures more fully comprise the film’s aesthetic appeal. Similarly, the attention to surface patterning is also central to poetry, in which the readers do not just decode its meaning; rather they pay attention to the ways in which the semantic features are patterned with rhyme, rhythm and alliteration.

This is notably the case when the animation is partially or wholly abstract. This can come in the form of visual music (which aspires to the dynamic and nonobjective qualities of traditional music), though not all experimental animations try to express an audio-visual equivalence. Abstraction warrants particular attention in this discussion however, since it played a key part in the development of experimental animation. In the early twentieth century, artists of the time were concerned about what was considered a ‘misuse’ of cinema. Robert Russett explains that they ‘envisioned motion pictures not as a form of popular entertainment, but rather as a new and dynamic expression, one closely allied with the major art movements of the day’. (Russett 2009, 10).

Painter Wassily Kandinsky claimed in 1911 that visual art should aspire to the achievements of music; that is, he sought a visual equivalent to music in contemporary painting. This led to abstract art. In Concerning the Spiritual in Art, he argues, ‘A painter [ … ] in his longing to express his inner life cannot but envy the ease with which music, the most non-material of the arts today, achieves this end. He naturally seeks to apply the methods of music to his own art. And from this results that modern desire for rhythm in painting, mathematical, abstract construction, for repeated notes of colour, for setting colour in motion’ (Kandinksy 2000, 21). Contemporaries of Kandinsky such as František Kupka and Paul Klee posessed similar creative aspirations.

By the 1920s, European abstract painters Walter Ruttmann, Viking Eggeling and Hans Richter extended their craft to animation (thus pioneering experimental animation as a field), with the musical organisation of film time as their central concern. Concepts from musical composition such as orchestration, symphony, instrument, fugue, counterpoint and score were applied. In turn, this necessitated audiences to pay special attention to the surface details of their films, rather than having surface details subordinated to the larger narrative. Richter’s Rhythmus 21 (1921) strips visual information back to its core element – motion in time. An assortment of squares and rectangles (sometimes white on black, other times black on white) expand and contract on the screen at different speeds. Each visual articulation, like a series of musical motifs, repeats and makes variations. Like music, the movements are variously fast, slow, aggressive, smooth, graceful and abrasive. Just as two or more musical melodies can move in counterpoint, so too can shapes in motion move contrapuntally around one another.7

While more recent experimental animators tend to produce figurative instead of abstract imagery, the surface detail remains a significant part of that overall experience. The work of William Kentridge, for example, intentionally features both the gesture of his charcoal markings and their subsequent erasure as part of the overall aesthetic effect. Likewise, one of the attributes that makes Allison Schulnik’s disquieting claymations compelling is the texture of the clay she uses to mould her figures.

Exposing the medium

In commercial animation, viewers aren’t typically invited to actively contemplate the materials used to make the film (e.g., cel animation, stop-motion or CGI). By contrast, experimental animation sometimes foregrounds its own materiality.8 This tendency harks back to modernist art in the early twentieth century. Clement Greenberg explains this by considering the transition from realistic paintings to modernist art:

Realistic, naturalistic art had dissembled the medium, using art to conceal art; Modernism used art to call attention to art. The limitations that constitute the medium of painting – the flat surface, the shape of the support, the properties of the pigment – were treated by the old masters as negative factors that could be acknowledged only implicitly or indirectly. Under Modernism these same limitations came to be regarded as positive factors, and were acknowledged openly.

(Greenberg 1991, 112)

Modernist paintings such as the works of Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse and Piet Mondrian stressed the flatness of the canvas rather than concealing it with illusions of visual depth. Flatness was unique to pictorial art, and was thus embraced.

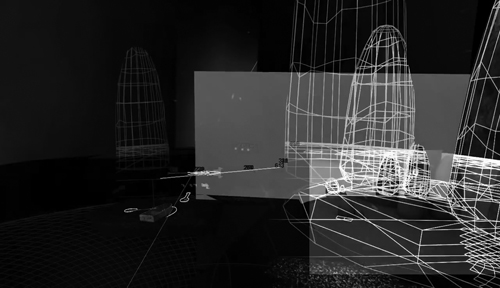

Exposing the materials of experimental animation is common, and it can be done in a variety of ways. Motion might be intentionally rough instead of smooth (undermining the illusion of natural movement), and in stop-motion the animator may choose to leave their fingerprints in the clay rather than smoothing them out. When artists like Len Lye scratch directly onto the film stock, their physical presence can be indelibly felt in the markings. Caleb Wood’s Plumb (2014) begins with a hand drawing pictures on a wall with a marker pen. There is a wide shot of the various markings, and then each one is shown in close up in rapid succession which creates an animation. David O’Reilly’s CG animated Black Lake (2013) pulls the viewer through an uncanny, hallucinatory underwater landscape with rocks, fish, a house and other objects. After a minute and a half, the same objects are seen in wire-frame form, exposing the way in which they were digitally generated (see Figure 1.2).

FIGURE 1.2 Still: Black Lake, David O’Reilly 2013.

Another way of exposing the materiality of animation is to make the audience visually register the frame rate of the film they are watching. If successive images are sufficiently different, a flicker effect occurs in which the viewer can discern every frame rather than relaxing the eye into the impression of smooth motion. Robert Breer’s Recreation (1956) applied the flicker effect, as did Paul Sharits’ T:O:U:C:H:I:N:G (1968). The technique is still frequently applied today with more recent films like Thorsten Fleisch’s Energie! (2007) and Jonathan Gillie’s Separate States (2016). The techniques used to create an animation, thus are something that may be exposed and celebrated in a variety of ways.

Conclusion

The central aim of this chapter has been to elucidate the underlying viewing strategies needed when engaging with traditional experimental animation.9 In doing so, I have outlined some of the major historical figures in the field and offered a working definition of experimental animation. In addition, some of the central principles have been detailed: The notion that these films evoke rather than tell, the discernible presence of the creative force behind the films, the centrality of surface details and exposing the materials used to make the film.

Before rounding this discussion off, a couple more issues may be briefly considered. First of all, it is also notable that experimental animation has received less critical attention than experimental film more broadly. Beyond visual music and synaesthetic film10 (which are closely related), there are no widely acknowledged categories for experimental animation unlike their live action counterparts such as the psychodrama, lyric film, structural film or ecocinema.11 Artist and curator Edwin Rostron suggests that this may be advantageous, commenting ‘[It’s] perhaps the general lack of critical attention historically that has allowed this area of work to escape being theoretically defined and pigeonholed too much – and to be honest as an artist I see this as a blessing! I find it exciting and interesting to work in an ill-defined area where anything goes and expectations are less clear’ (Rostron 2017).

The relationship between experimental animation and commercial films may also be explored in more detail. Just as the term avant-garde is of military origins, meaning ‘advance garde’, implying (in the artistic context) pioneers who lead the way for the commercial realm, experimental animators influence mainstream aesthetics. This can occur in the realm of special effects, where artists like Michel Gagné can produce abstract animations like Sensology (2010) and also use the same techniques for special effects in Ratatouille (2007). Title sequences can also be influenced by experimental animation such as the opening to Scott Pilgrim Vs. the World (2010), which is a homage to the scratch films of Len Lye and Norman McLaren. Animator Gianluigi Toccafondo also began his career producing experimental animations like La Coda (1989) and La Pista (1991) and later produced title sequences for feature films such as Robin Hood (2010) with an aesthetic adapted from his earlier style. Finally, music videos have also been influenced by experimental animation. Robyn’s 2007 video to ‘With Every Heartbeat’ features a homage to Oskar Fischinger’s Composition in Blue (1935), and the video to ‘Where Are Ü Now’ (2015) by Skrillex, Diplo and Justin Bieber draws straight from the sketchy, flicker aesthetic pioneered by Robert Breer.12

One may ask: When writing about experimental animation, what does one discuss? This question is particularly pertinent when considering this type of film – how does one talk about a film that often tries to express the inexpressible? This four-step plan may offer a helpful starting point:

• To begin with, vividly describe the artwork. This will show that you were sensitive to the details of the film rather than just experiencing them as a flurry of vague, generalised images.

• Summarise existing material on your chosen artist case study. Outline what their ‘larger project’ or general approach is. This has happened briefly in this essay in relation to Jordan Belson and David Theobald.

• Articulate the creative aspirations of the artist by matching it with specific moments of their film.

• If you can discern one, offer your own interpretation of the film which hasn’t been expressed elsewhere.

In experimental animation, images come from the quick-of-the-soul. An artist listens to their muse, and shares their vision with the outside world. As the viewer, your principal duty is to relax, keep an open mind and let the film do its work.

Notes

1 Specifically, Reinhardt was referring to abstract painting. But the same principal may be applied to modernist and postmodernist art more generally.

2 There are a host of other important figures from this period that are detailed in Russett and Starr’s Experimental Animation: Origins of a New Art, such as Lillian Schwartz and Stan Vanderbeek. But for the sake of brevity, they have been left out of my discussion. However, more can be learned about them, and others, in Russett and Starr’s book.

3 It is, however, notable that some of the 1970s surrealist independent animations such as Suzan Pitt’s Asparagus (1979) took on themes of feminism and identity politics.

4 See: Bordwell, David. ‘The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice.’ Film Criticism 4, no. 1 (Fall 1979): 56–64.

5 See Fred Camper’s ‘On Visible Strings’ and Miriam Harris’ ‘Drawing Upon the Unconscious: Text and image in two animated films by Robert Breer and William Kentridge’ for more detailed analyses of this film.

6 Ying Tan insightfully comments that as well as absorbing all that have something to contribute to art such as all religions, cultures, science and technology, Belson’s films emphasise the intuitive over the intellectual, they speak of experience as an earthly human being, and may be understood as sacred art. See: Tan, Ying. ‘The Unknown Art of Jordan Belson’. Animation Journal. Spring 1999: 29.

7 See Aimee Mollaghan’s article in this collection for a more detailed discussion of visual music.

8 Note that the articles in this collection from Miriam Harris, and Dan and Lienors Torre also discuss materiality in animation.

9 The word ‘traditional’ is used in this instance because the form has developed and extended into other fields such as motion graphics, music videos, multiple screen and site-specific projections and interactive platforms. Each of these warrant their own focused consideration.

10 See: Taberham, Paul. ‘Correspondences In Cinema: Synaesthetic Film Reconsidered”. Animation Journal 2013: 47–68.

11 For definitions of the psychodrama, lyric film and structural film, consult Sitney, P. Adams. Visionary Film. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001. For ecocinema, see Scott MacDonald, ‘The Ecocinema Experience,’ in Ecocinema Theory and Practice, edited by Stephen Rust, Salma Monani and Sean Cubitt (New York: Routledge, 2013).

12 Michael Betancourt’s article in this collection explores the intersection between experimental animation and the commercial realm in more detail.

References

‘Edges: An Animation Seminar.’ 2016. edgeofframe.co.uk. www.edgeofframe.co.uk/edges-an-animation-seminar

Allers, Roger and Rob Minkoff . The Lion King. US, 1994. Film.

Bell, Kristine and Anna Gray . Ad Reinhardt: How to Look. Art Comics. Hatje Cantz, 2013.

Belson, Jordan quoted in MacDonald, Scott. A Critical Cinema 3: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers. London: University of California Press, 2009.

Belson, Jordan. Allures. US, 1961. Film.

Bocqulet, Ben. The Amazing World of Gumball. UK and US, 2011–Present. Television series.

Bieber, Justin. Where Are Ü Now. US, 2015. Film.

Bordwell, David. ‘The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice.’ Film Criticism 4, no.1 (Fall 1979): 56–64.

Bordwell, D. and Kristin Thompson . Film Art: An Introduction. 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2008.

Bird, Brad. Ratatouille. US, 2007. Film.

Breer, Robert. Recreation. France, 1956. Film.

. Bang! US, 1986. Film.

Buck, Chris and Jennifer Lee . Frozen. US, 2013. Film.

Camper, Fred. ‘On Visible Strings’. Chicago Reader June 5, 1997, accessed November 2018. www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/on-visible-strings/Content?oid=893567

Chomet, Sylvain. The Illusionist. France and UK, 2010. Film.

Clements, Ron and John Musker . Treasure Planet. US, 2002. Film.

Coté, Guy. ‘Interview with Robert Breer. Film Culture 27 (Winter 1962/63): 17.

Disney, Walt. The Silly Symphonies. US, 1929–1939. Film.

Elliot, Adam. Mary and Max. Australia, 2009. Film.

Fischinger, Oskar. Composition in Blue. Germany, 1935. Film.

Fleisch, Thorsten. Energie! Germany, 2007. Film.

Gagné, Michel. Sensology. France, 2010. Film.

Gillie, Jonathan. Separate States. UK, 2016. Film.

Furniss, Maureen. Art in Motion: Animation Aesthetics. New Barnet Herts: John Libbey Cinema and Animation, 2009.

Geronimi, Clyde, Wilfred Jackson and Hamilton Luske. Lady and the Tramp. US, 1955. Film.

Greenberg, Clement. ‘Modernist Painting.’ In Art Theory And Criticism: An Anthology Of Formalist Avant-Garde, Contextuaist And Post-Modernist Thought, 1st ed., London: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1991, 112.

Hanna, William and Joseph Barbera. Tom and Jerry. US, 1940–1958. Film.

Hertzfeldt, Don. It’s Such a Beautiful Day. US, 2012. Film.

Hand, David. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. US, 1937. Film.

Harris, Miriam. ‘Drawing on the Unconscious: Text & image in two animated films by Robert Breer and William Kentridge.’ CONFIA International Conference of Illustration & Animation in Barcelos, Portugal, June 2016, published proceedings: CONFIA 2016.

Husbands, Lilly. ‘Animated Alien Phenomenology In David Theobald’s Experimental Animations’. Frames Cinema Journal 5, 2015, accessed July 2014. http://framescinemajournal.com/article/animated-alien-phenomenology-in-david-theobalds-experimental-animations/

. In: M. Harris, L. Husbands and P. Taberham, eds., Experimental Animation: From Analogue to Digital. New York: Routledge, 2019.

Jones, Chuck. Road Runner. US, 1949–1965. Film.

Kandinsky, Wassily. Concerning the Spiritual in Art. New York: Dover Publications Inc., 2000.

Larkin, Ryan. Walking. Canada, 1968. Film.

Le Grice, Malcolm. Experimental Cinema In The Digital Age. London: British Film Institute, 2009.

Mollaghan, Aimee. The Visual Music Film. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Paronnaud, Vincent and Marjane Satrapi . Persepolis. France and Iran, 2007. Film.

Puglisi, John. Legend of the Boneknapper Dragon. US, 2010. Film.

O’Reilly, David. Black Lake. Ireland, 2013. Film.

. The External World. Germany and Ireland, 2012. Film.

Pitt, Suzan. Asparagus. US, 1979. Film.

Richter, Hans. Rhythmus 21. Germany, 1921. Film.

Robyn. With Every Heartbeat. Sweden, 2007. Film.

Rosenbaum, Jonathan. ‘ROOM 237 (and a Few Other Encounters) at the Toronto International Film Festival, 2012.’ jonathanrosenbaum.net. 2018. www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2018/01/room-237-and-a-few-other-encounters-at-the-toronto-international-film-festival-2012/

Rostron, Edwin. Letter to Paul Taberham. “Re: Edge Of Frame Seminar Audio”. Email, 19th February 2017.

Russell, Erica. Triangle. UK, 1994. Film.

Russett, Robert. Hyperanimation. New Barnet: John Libbey, 2009.

Scott, Ridley. Robin Hood. UK and US, 2010. Film.

Sharits, Paul. T:O:U:C:H:I:N:G. US, 1968. Film.

Smith, Murray. ‘Modernism and the Avant-Gardes.’ The Oxford Guide to Film Studies. Edited by John Hill and Pamela Church Gibson . New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Taberham, Paul. ‘Correspondences In Cinema: Synaesthetic Film Reconsidered.’ Animation Journal 2013: 47–68.

Theobald, David. Jingle Bells. UK, 2013. Film.

. Night Light. UK, 2016. Film.

Toccafondo, Gianluigi. La Coda. San Marino, 1989. Film.

. La Pista. Italy, 1991. Film.

Wells, Paul. Understanding Animation. London: Routledge, 1998.

Wright, Edgar. Scott Pilgrim Vs. the World. UK, 2010. Film.

Wood, Caleb. Plumb. US, 2014. Film.

Youngblood, Gene. Expanded Cinema. USA: E.P. Dutton, 1970.