Experimental Animation and Motion Graphics

Michael Betancourt

Motion graphics encompasses a diversity of production techniques, ranging from ray-traced 3D computer animations to optically printed composite cinematography and traditional cel animation. Although the first designs produced in the United States that are recognisable as ‘motion graphics’ were made for the Hollywood studios at Leon Schlesinger’s Pacific Art and Title Studio starting in 1919 (and called ‘Art Titles’) (‘Pacific Title & Art Studio to be liquidated’ 2009), the contemporary field emerged from the particular historical context in the United States after the Second World War as Modernism became the dominant approach to design (Betancourt 2013). While the range of applications on TV (broadcast design) includes station identity graphics and advertisements, and the use of motion graphics in commercial narrative films appears prominently as the title sequence, their vast scope also includes video games and interactive digital software, confounding any attempt to briefly survey them because contemporary digital animation/compositing software such as Adobe AfterEffects has lowered the production costs and technological barriers to entry, allowing motion graphics to become a common part of everyday experiences with all media, even billboards next to highways. These ubiquitous and prosaic, even banal designs – commercials, title sequences and various ‘other’ animated materials now appearing on TV, in video games and in film – are commercialisations of the historical avant-gardes as popular mass media. Literary critic Larry McCafferty called these transfers ‘avant-pop’ in the 1990s: The comingling of avant-garde aesthetics and techniques with commercial priorities of realism, accessibility and ease-of-comprehension (McCafferty 1995).

This chapter summarises how the ‘avant-pop’ transformation of the abstract traditions of ‘visual music’ became motion graphics, using the title sequence as an illustration. The choice of title sequences for this discussion is utilitarian: They offer abundant and readily accessible examples of these relationships for analysis; unlike other applications of motion graphics, such as the ephemeral graphics of broadcast design and advertising that become inaccessible after their limited time of initial use, only the title sequence remains accessible over time, making these designs valuable for historical analysis since they continue to influence later designers long after more ephemeral animations are forgotten, and thus provide an on-going link to earlier, avant-garde sources.

The concept of ‘avant-pop’ reveals the role of film and television in promoting Modernist art in the 1950s and 1960s (MacDonald 2010, 214–215) through the commercial embrace of experimental animation, avant-garde film and video art (Jacobs 1975, 543–544). The realist and narrative meanings attached to motion graphics differentiate these uses from those of the avant-garde, beginning during the 1950s – for example, with John Whitney’s graphic, spiralling forms used in Saul Bass’ Vertigo title sequence (1958) to suggest a literal ‘vertigo’; this conversion of abstraction-into-realism is what distinguishes the commercial design from its avant-garde sources. Commercial media converts the abstract into a stylised variant of familiar representational content (Betancourt 2016); the adaptation in Vertigo is typical. Whitney, who worked simultaneously on commercial design projects and his own abstract films (Sandhaus 2014, 158), promoted these adaptations, first at the Aspen Design conference in 1959, then on an on-going basis throughout the 1960s. His work directly makes aesthetic and technical transfers between avant-garde film/video and motion graphics. The video artist Ron Hays (Folkart 1991) also promoted the heritage of visual music for commercial production. Like Whitney, he initially developed his theory of music-image from avant-garde film making (Hays 1974), applying it in his video art (as with his tape Space for Head and Hands, 1975). He utilised the same imagery and techniques in commercial music videos (as in Earth, Wind and Fire’s ‘Let’s Groove,’ 1981).

The heritage of visual music as a formal arrangement of sound-image relations, as well as a set of visual techniques is abundantly apparent in both music videos and title sequences. However, it is not simply a question of synchronisation. Interlocking concerns with synaesthetic form, the painterly/graphic organisation of space, and experimental animators’ use of optical printing and computer technology also occupy central positions in the commercialisation of motion graphics. This heritage is especially apparent in the design and organisation of feature film title sequences. Designs such as Saul Bass’ The Man With The Golden Arm (1955), which adapts elements of Hans Richter’s abstract film Rhythmus 21 (aka Film ist Rhythmus, 1923), or Simon Clowes’ design for X-Men: First Class (2011) that borrows from a range of historical films (such as Walter Ruttmann’s absolute films of the 1920s1 and the works of Mary Ellen Bute) are exemplars of the ‘avant-pop’ approach that defines how motion graphics engages with experimental animation. Clowes’ title design makes this ‘avant-pop’ engagement with historical abstraction explicit through a transformation of Modernist experimentalism into a representation of genetics and gene sequencing. Similar quotations from Mary Ellen Bute’s Tarantella (1940) organise the title design for the French film Ça Ce Soigne? (Is It Treatable? 2008). These references draw attention to the established character of the visual music imagery in experimental animation as a language for recombination and manipulation by motion graphics.

The title sequence for The Man With The Golden Arm (1954) designed by Saul Bass is a nexus assimilating these influences from historical animations that, in turn, became a central reference for future motion graphics designs. In mediating these transfers between experimental and commercial animation, this title sequence reveals the intersection of otherwise independent histories. In his 1961 introduction to ‘The Title Makers,’ an Adventureland segment on his TV show Walt Disney Presents, Walt Disney inadvertently explained how the prestige given to Bass’ design links experimental animation to the innovations of motion graphics:

Now, time was, you know, when you could open a motion picture merely by flashing its title on the screen, and listing the names of the people who helped put it together, but not anymore! We’ve reached the point where almost everybody wants to make a bid for the title as the “most ingenious” of the title makers. It has become a real challenge to devise a sequence that is fresh and interesting and entertaining. Also according to theory, it should also help to get the audience into the proper frame of mind.

(Disney 1961)

The historical source for these ‘ingenious’ approaches to animation in title sequences was avant-garde film. The impact of this tradition is obvious in how it ‘directs’ what appears in title designs by Saul Bass. The Man With the Golden Arm makes the connections between visual music animations and motion graphics explicit. The ‘birth’ of the field as a commercial enterprise in the post- Second World War period depends on Bass’s fusion of film titles with International (‘Swiss’) Style graphics (Spigel 2008) and the abstract animated films of the 1920s and 30s. The history of the abstract or ‘absolute’ film’s technical-aesthetic development during the two decades prior to the general embrace of synchronous sound recording by the film industry in 1927 (Betancourt 2013) applied avant-garde experiments in abstract painting to motion pictures. Musical analogies (Tuchman 1985; Brougher 2005)2 are common in all the ‘silent’ films that provide the sources for title designs such as The Man With The Golden Arm. This title sequence in particular provided a model to emulate and a standard to challenge over the next two decades.

Ralph K. Potter, Director of Transmission Research at Bell Laboratories, who collaborated with abstract film-maker Mary Ellen Bute in designing the oscilloscope control device she used to make her Abstronics films (Potter 1951), was closely involved in promoting avant-garde film to advertising directors as a source of innovation and aesthetics for their TV commercial designs in the 1950s. Potter writes:

Of all the film societies in the country none has influenced the creative television artist more than Cinema-16. Their experimental, avant-garde and new art forms pop up with amazing regularity. [ … ] While many of [Vogel’s] highly volatile films evaporate into nothingness or obscure points of aesthetics, most are excellent visual barometers for the graphic artist. Agency Art Directors and film producers flock to view these private showings. Much of what they see eventually finds its way into TV commercials.

(Potter 1961, 63)

The title of Potter’s article, ‘Sources of Stimulus: TV Commercials Often Draw on Avant-Garde Films,’ makes the connection between non-commercial experimental film and commercial motion graphics explicit. The embrace of Modernist approaches to art (Spigel 2008, 217–218), especially those employed by the avant-garde, were also engaged by graphic designers during this period as a way of demonstrating a collective embrace of Modernism (Whitney 1980, 156). The ‘visual music film’ is a pervasive foundation; contemporary motion graphics have been shaped by and continue to draw from this history, even as production technology has drastically changed. This embrace of Modernist design in a highly commercial medium where business concerns determined the aesthetic forms chosen is symptomatic of the transfers between the art world and commercial world that surrounded television production in the 1950s and 1960s (Currie and Porte 1967, 16). However, following Potter’s suggestions and the readily accessible programmes at Cinema-16 in New York, early television became the primary source of direct crossover from the independent productions of artists to the corporate productions of television (Sutton 2011), visible in the initial emergence of motion graphics as ‘broadcast design’ (Whitney 1980, 156).

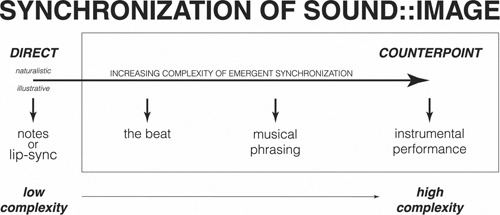

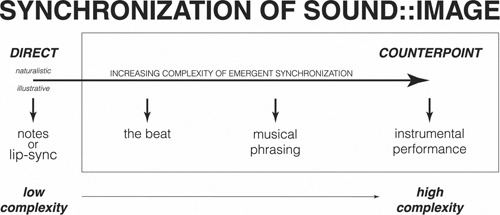

Approaches to visual music are historically limited in scope and application to particular types of musical composition and only to arrangements of visual imagery evoking a synaesthetic experience based in a correlation between the sound and either an immanent form seen on screen, or through an emergent relationship between the visible sync-points and the audible sync-points provided by the beat, musical phrasing or the performance of individual instruments (see Figure 3.1). The range of artists influenced by how ‘visual music’ arranges sound and image cuts across the boundaries between movements, media, and decades of time to reveal a consistent interplay of abstract form, synaesthesia, and synchronisation (Tuchman 1985).

FIGURE 3.1 Synchronisation of Sound: Image. Diagram by Michael Betancourt.

Visual music films use synchronisation to translate the cultural/ideological meaning common to abstraction (the visualisation of a transcendent spirituality) into a physical phenomenon comparable to ‘lip-sync’ in its immediacy of connection between sound and image. The role of ‘visual music’ in the abstract films made by Walter Ruttmann, Viking Eggeling, Hans Richter and Oskar Fischinger, as well as American Mary Ellen Bute, realise synaesthesia as an immanent phenomenon, either through a direct analogy to music or by creating a counterpoint of sound and motion/editing, demonstrating visuals comparable to music. Many of their films were readily available for viewing during the formative years of motion graphic’s emergence during the 1940s, either at movie theatres, or in specialised screenings. Baroness Hilla von Rebay, the first director of the Museum of Non-Objective Painting (later renamed the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum), sponsored screenings of abstract films acquired from Hans Richter in 1940 and worked to make experimental animation generally more accessible to the public. The network of relationships between abstraction, synaesthesia and visual music reveal more than just a set of congruencies – it is a ‘fine art approach’ originating in the avant-garde that has been adapted for commercial use (the field of ‘motion graphics’ is this use). Considering this heritage illuminates the complex role and aesthetics of synaesthetic form for motion graphics – immediately apparent in how synchronisation (including music, sound effects and voice-over narration) is a definitive formal constraint. In motion graphics the visuals explicitly function as an illustration of the soundtrack.

Synchronisation links abstract forms to music, equally demonstrating and reinforcing the link between motion graphics and earlier visual music animations. The counterpoint synchronisation employed in title sequences such as the design for The Seven Year Itch (1955) by Saul Bass connects musical sync-points to the graphic animation/transitions between title cards. Their connections are metaphoric. The ‘windows’ that fold open and closed to present each credit in this design move simultaneously to musical cues provided by the score. When the audience hears a note, they see a simultaneously corresponding motion appear on-screen, creating an apparently ‘natural’ connection that masks the arbitrary nature of their construction. Abstraction and visual music present the ideo-cultural belief in a ‘spiritual’ reality made tangible-visible through a combination of visual form – whether graphic or typographic is irrelevant – creating a synaesthetic experience (Moritz 1999) where synchronisation with sound acknowledges its sources in earlier visual music animations.

Prestige via title design

When motion graphics employ music, they follow the model of visual music (Betancourt 2013) animations, linking the design directly to the score. The Man With The Golden Arm is a notable early example in which this synchronisation is looser, contrasting with Bass’s later designs where the same formal idiom derived from International (‘Swiss’) Style graphic design is more precisely synchronised (Spigel 2016). The sequence runs approximately two minutes, which was the most common length for title sequences since the 1920s; his later designs have a longer running time that allows for more complex audio-visual relations and additional imagery not connected to individual credits. This sequence was Bass’ first graphic animated title, composed from 16 static title cards with animated transitions. It begins clearly synchronised but gradually drifts into syncopation: The notes come slightly before or slightly after the visual sync-point in a reiteration of the syncopation common to jazz music. The syncopated drift only returns to a close synchronisation for the final animorph into a graphic arm at the conclusion of the sequence. Bass has connected his design to the film’s narrative about a white Jazz musician’s struggle with heroin addiction – summarised iconically by a twisted, graphic icon of an arm that is at the same time a literal visualisation of the film’s title. The immediacy of connection between the imagery and the film’s title is common to feature film title sequences (Betancourt 2018, 57–58). The series of white lines evoke needles, inviting an acknowledgement of the syncopation as the impact of intoxication and addiction. Thus the design can be understood as a literal restatement of the drama, addiction made apparent as the inability of these elements to remain precisely synchronised, the animorph transforming this narrative information into the formal logo/decoration. This arm also appears prominently in the film posters and other advertising. It was the first time a post- Second World War film employed the same designs in both titles and advertising posters.

These same needles/lines also evoke Richter’s first film, Rhythmus 21, a work crucial to the transfer between experimental animation and motion graphics. After the Second World War, Hans Richter engaged in historical revisionism, claiming his own film, Film Ist Rhythmus (1923, which he retitled Rhythmus 21 and added a title card stating ‘Realisé en 1921’), as the first abstract film ever produced. Showing an animation of white and grey lines, paper rectangles and squares moving against a black background, the film does not appear to have had a public screening prior to the last Paris Dada performance, the Soirée du Cœur à Barbe in 1923 where it appears on the programme (Elsaesser 1996, 15). The ‘history’ Richter contributed to the Art in Cinema catalogue that prioritised his work above that of Ruttmann would be repeated and expanded upon in the years following its publication, both by Richter and by other writers (Weinberg 1951). Richter helped secure this position by selling 35mm prints of his own films to both the Museum of Modern Art and the Museum of Non-Objective Painting along with a collection of works by Duchamp, Leger and Eggeling. These films enabled both institutions to promote Richter’s version of history through their screening series. Museum of Non-Objective Painting Director Rebay’s weekly screening of abstract animation made Richter’s films both readily accessible and highly visible in New York starting in the 1940s; they would also figure prominently in Frank Stauffacher’s 1946 programme Art in Cinema (MacDonald 2010, 3). From 1942 to 1956, Richter was the director of the Film Institute of the City College of New York, a position he used to promote his revisionist history of avant-garde and abstract film that gave his work priority (Lukach 1983). Being first meant that Richter’s film was guaranteed prestige in any programme that showed it. It is precisely this elevated status that his revisionist history was intended to produce, and the impact of this prestige function is readily apparent in Bass’s design-animation for The Man With The Golden Arm, which emulates the first abstract film.

The pioneer of Modernist broadcast design, William Golden, was appointed Creative Director of Advertising and Sales Promotion in 1951, making him the designer and art director responsible for CBS’s print and on-air designs from their head office in New York. He was also responsible for the Modernist transformation of broadcasting that began immediately with his assumption of the role in 1951. His view that design was not art, but a specific variety of craft, is apparent in the organisation of a small department of 39 employees that embraced innovation and functioned autonomously within the corporate structure of CBS (Spigel 2008). Golden explained his views at the Aspen Design conference in 1959:

Once he stops confusing Art with design for Business and stops making demands on the business world that it has neither the capacity nor obligation to fulfill, [the designer will] probably be all right. In fact I think he is pretty lucky. In the brave new world of Strontium-90 – a world in which craftsmanship is an intolerable deterrent to mass production – it is a good thing to be able to practice a useful craft.

(Golden 1962, 63)

Golden used Modernist design to promote CBS as the ‘prestige’ TV network (Stanton 1962, 9). This connection of prestige to Modernism explains the design choice for Saul Bass’ poster and title sequence designs for The Man With The Golden Arm. Unlike TV, feature films were already being accorded a high degree of respect and significance. The simple, graphic imagery of this design led to an association of the white line as a signifier of modernity embraced by broadcasting in particular: The titles for TV shows such as The Twilight Zone (1959), Boris Karloff’s Thriller (1959), Bus Stop (1961) The Outer Limits (1961), Mission Impossible (1964), The Time Tunnel (1967), and The Brady Bunch (1969) repeat this singular element in spite of their otherwise divergent contents. Across all these cultural shifts and aesthetic changes, the role of title sequences as signifiers of prestige that orchestrate audio-visual materials in counterpoint to their credit-texts is consistent.

The reappearance of these white lines in TV title sequences is a reflection of the prestige function of Modernism that Walt Disney described in 1961. It is also an ongoing reassertion of motion graphic’s foundations in experimental animation. Throughout the 1960s, the ‘designer’ (i.e., Modernist) title sequence remained a signifier for serious, important cultural production. The presence of this graphic element in these TV title designs is almost illogical – it has only a limited role in their construction (it is not integral to them so much as precisely a transitional element deployed within them) – and its function shifts, depending on the sequence that employs it: As a door edge seen in The Twilight Zone, or the ‘fuse’ of Mission Impossible that runs through the entire montage sequence, or as a visual pause before becoming typography (Time Tunnel) or boxed portraits (The Brady Bunch) – transforming its role for each specific design. Its reappearance throughout this period as a graphic quotation-reference signifies the Modernity of the programme that follows. These references create a succession of attribution and borrowed significance that began with Bass’s quotation of Richter’s film in The Man With The Golden Arm. The appearance of the white line as an icon of Modernity in television programs during the 1950s and 1960s reveals their aspirational character: That TV aspires to the cultural significance and respect accorded to serious art – thus the adoption and use of avant-garde techniques in ‘avant-pop’ not only makes sense, it shows these aspirations in action.

Contemporary quotations

Within contemporary motion graphic design, these quotations of earlier animation and visual music films have remained an implicit dimension of their sound-image synchronisation. This emergence of an intertextual and explicitly quotational commercial/popular media coincides with the same trends of convergence between popular culture and the avant-garde apparent in McCafferty’s term ‘avant-pop’ itself. Semiotician Umberto Eco recognised that those approaches to repetition and quotation that once were almost exclusively the domain of the avant-garde have become a commonplace part of media (Eco 1994, 96). The relationship between immanence and memory – or novelty and schema (Eco 1994, 96) – is a domain of concern specific to semiotics and how it has been applied to the analysis of storytelling. However, some contemporary designs engage with this history of visual music and experimental animation more-or-less explicitly, producing designs that invite contemporary audiences to draw on their encyclopedic knowledge of both motion graphics and abstract film. These designs engage with their historical sources in ways that recall Eco’s comments in ‘Interpreting Serials’ about the role of quotation in contemporary media:

Aware of the quotation, the spectator is brought to elaborate ironically on the nature of such a device and to acknowledge the fact that one has been invited to play upon one’s encyclopedic competence.

(Eco 1994, 89)

Unlike ‘independent’ design, this type of intertextual work anticipates the audience’s recognition of its quotational basis. This ‘post-modern aesthetic solution’ depends on the audience being aware of both the source of the quotation and how the new context transforms it. These intertextual works necessarily divide the audience into those members who recognise and understand the references and those who do not. Only the audience members who identify the source engage with the serial aspects of the design. The role of quotation in Eco’s ‘serial form’ is an inherent part of his theory: All serials by nature must be quotational to be serial, but it must also be identified – recognised – by the audience. His theory of ‘serial form’ directs attention to how the audience apprehends the work, for instance which intertextual references and quotations they identify and understand. His conception of the audience is as an actively engaged interrogator of what it encounters, anticipating and evaluating the ‘serial’ work as it progresses. Starting with The Man With The Golden Arm and continuing into contemporary title designs, this intertextual dimension unites the commercial and non-commercial aspects of the visual music tradition. For knowing audiences, the explicit quotation in the design is precisely what makes the work interesting. It is also in these designs that the relationship to both experimental animation and the abstract, visual music film becomes evident. In making their quotational references apparent, such designs reveal the formative role that avant-garde animations have played in the formulation of motion graphics as a discipline.

The intertextual references to historical visual music films in title sequences such as Ça Ce Soigne? (Is It Treatable? 2008) and Scott Pilgrim vs. The World (2010) complicate interpretations of their counterpoint synchronisations, transforming the focus of these designs from immanent perception to memory. They challenge the subordinate role of title sequences by shifting meaning from the immediacy of both paratext and the audiovisual connection to other, parallel meanings evoked through the recognition of historical references via quotation that directs the audience to consider influences and content from their established knowledge. The audience’s recognition of earlier films being reiterated or otherwise evoked by contemporary designs directs their attention away from the immanent work to a consideration of its place within this larger history; this historical mediation is explicit for some artist-designers such as Ron Hays. It is worth remembering that some of these historical films, notably those of Walter Ruttmann and Oskar Fischinger in Germany, Len Lye in Britain and Mary Ellen Bute in the United States were produced for and exhibited in commercial movie theatres either as short subjects in their own right, or as hybrid entertainment-advertisements. Their avant-garde and experimental aspects do not circumscribe their equally important connections to the commercial enterprise of motion pictures, a relationship that continues with contemporary motion graphics.

The one minute, forty-five second title sequence of the French comedy Ça Ce Soigne? was designed by Julien Baret at Deubal, the French motion graphics studio founded by Stéphanie Lelong and Olivier Marquézy. It begins with the sound of an orchestra ‘tuning up’ paired with an animation of red squares arranged in a semi-circle. Their motion suggests they represent people finding their seats before a performance. As the music starts, a series of white lines appear on-screen. This initial opening is not an example of counterpoint: For each note played, a white line appears in an arc on-screen – an instance of direct synchronisation: for each note played, a line moves in unison. This opening presents an immediate assertion of ‘visual music’. These white lines are a visual quotation from the start of the Bach sequence in Walt Disney’s 1940 feature Fantasia, rather than a reference to The Man With The Golden Arm. This intertextual quotation from the Disney film gives Ça Ce Soigne? a second level of meaning parallel to its use of the traditions of visual music. The shift this recognition entails challenges the directness of its audio-visual synchronisation by drawing attention away from the immanent work and into a reverie prompted by identifying the quotations. Because the intertextual relationship is explicit (i.e., audience recognition of quotations that blatantly play on intertextuality can be anticipated), the result draws attention to itself, rendering the title sequence for Ça Ce Soigne? as a work of visual music about visual music. This quotational intertextuality redoubles the already referential dimensions of title design generally, a link that brings the aesthetics of the design itself into consideration quite apart from whatever narrative connections it might have to the story that follows.

Intertextuality in both designs depends on its audience specifically recognising and understanding an alternative, counter-interpretation submerged within the design – its interpretation proceeds through memory, necessitating a distancing from the immanent event to apprehend its organisation as not an original invention, but a novel transformation of an established and already-known form. This role for memory and past experience in recognising counterpoint synchronisation in Ça Ce Soigne? explicitly becomes a part of its design and formal organisation as visual music. Intertextual references are an excess in the literal sense; it is an addition that directs attention outwards, away from the narrative linkages that define titles as a paratext, challenging this subordination by drawing audience attention towards the (absent) sources. This title sequence begins with simple geometric shapes – red squares – arranged in a semi-circle; however the movement of these shapes suggests an audience taking their seats, awaiting a performance. Meanwhile an orchestra ‘tunes up’ on the soundtrack. When the music begins with white lines synchronised to notes and progresses into geometric patterns and jagged, rhythmic lines, these abstract forms become progressively more representational – pills, crying eyes, a heart monitor and skull formed from abstracted tears – while retaining their abstract appearance. The film’s narrative about a hypochondriac determines the representational character of the animated elements synchronised with the music. An entirely graphic animation, the ‘graphics’ shift between recognition – as pills, drops of blood the jagged plot of a heart monitor – and kinetic abstraction as the visual counterpoint to Camille Saint-Saëns’ composition Danse Macabre (1874). In visualising this relationship to the narrative, the various ‘abstract’ forms in the title sequence become representational. These images move between abstraction and representation, all evoking the film’s title – ‘is it treatable?’ – through their connection to medicine and medical treatment. The doubling that intertextuality poses within the title sequence expands the recognitions specific to counterpoint synchronisation beyond the typical dynamic that arises between the title sequence and the narrative that follows it. The intertextual references to Fantasia link this opening to visual music, but these references are not limited to the opening of the sequence. As it progresses, other quotations to the jagged and angular animations in Bute’s film Tarantella (1940) – music that makes its own reference to the dance that supposedly could cure the ‘deadly bite of the tarantula’ – provide an additional level of commentary that suggests the entire narrative about a depressed symphony conductor who may merely be suffering from hypochondria.

A similar play of quotation and design informs Richard Kenworthy’s title sequence design for Scott Pilgrim vs. The World (2010). It contains the same play of intertextual quotation from the history of experimental animation that appears in Ça Ce Soigne?. As Eco notes, the audience’s past experience determines meaning. This division of audiences into witting and unwitting enables the title sequence to become an indicator of the film’s importance (prestige), not simply through who the designer is, but as a formal part of the design itself. This intertextual approach is particular to title designs produced since the 1990s, a reflection of Eco’s recognition that as serial form becomes the dominant approach to intertextuality and design, it challenges the paratextual relationship of title sequence to narrative by rendering the titles formally and conceptually distinct from their attachment to the primary text. The history of abstract, avant-garde and experimental animation is crucial to the consideration and interpretation-recognition of these title sequences.

Because Scott Pilgrim vs. The World imitates the appearance of traditional ‘direct animation’ – painting, scratching and drawing directly onto celluloid to create imagery on the filmstrip without using photography – its intertextuality is both formal and visual. This technique, (in use since the Futurists Bruno Corra and his brother Arnaldo Ginna (2001, 66–67) created their first films in 1909, discussing them in the manifesto ‘Abstract Cinema—Chromatic Music’) has a close association with the historical avant-garde. Both Len Lye and Norman McLaren worked extensively with this technique, and their films provide a referent for the digital animation in Kenworthy’s design. The aesthetics of ‘direct animation’ strikingly contrasts with the sharp vector graphics embedded throughout Scott Pilgrim vs. The World. Even though the film’s visual design exhibits a wide range of animated typographies and graphics resembling comic books and video games, the title sequence retains a distinct character that is not repeated elsewhere. Its organisation evokes a kinetic play of graffiti and urban scrawls rather than the kinetic abstraction it quotes. Counterpoint synchronisation separates these animated graphics from the other narrative graphics. Flat and highly saturated, they are also gritty and scratched – their irregularity betrays their origins in handwork done directly on physical material.

This second level of meaning – in excess to those references in the design that are proximately concerned with the narrative (the paratextual functions of the title sequence) – opens its interpretation beyond the confines of its pseudo-independence. No longer a subordinate design, the interpretation of these openings proceeds without concern for linkages between title design and the film it ‘opens’. The ‘reward’ for doing so is the establishment of the title as an independent entity, effectively separate from the narrative that follows, which is the raison d’être for the titles as such.

In being appended to the narrative, the title sequence functions as a synecdoche that requires the decoding made possible only through the narrative as such. The intertextual quotation adds to this displacement a second level hidden from the narrative interpretation that changes the title sequence into a mediator between the proximate encounter with the motion picture and the cultural foundations of its production. By introducing this anteriority into the design, the quotations that organise and inform both Ça Ce Soigne? and Scott Pilgrim vs. The World demand that the ideological content manifested through synchronisation no longer remain invisible. The same artifact character provided by using known, already-established music (Camille Saint-Saëns’ Danse Macabre) must be extended to the animation, and potentially even the narrative itself. The audience’s recognition of familiar music (even when the composer and title remain unknown) always has this intertextual quality – déjà entendu – that finds its analogue in visual intertextuality.

Commercialisation: Synaesthesia and realism

The same process of rendering visible an unseen, transcendent ‘reality’ that is particular to the visual music tradition organises the synchronisation of motion graphics even when they are not immediately or obviously abstract: Synchronisation that illustrates sound creates the same analogy of sound-to-image as the realist approach of naturalistic ‘lip-sync’ in motion pictures. As historian Christopher Williams notes in the introduction to his study of realist theories in cinema, realism tends to disappear into arguments about what is ‘real’ rather than remain concerned with the aesthetic form – mimesis – it describes, creating an explicit parallel between a realism of surface appearance and a ‘deeper realism’ normally obscured. He writes:

The debate about realism can perhaps best be grasped through the opposition between ‘mere appearances,’ meaning the reality of things as we perceive them in daily life and experience, and ‘true reality,’ meaning an essential truth, one which we cannot normally see or perceive, but which, in Hegel’s phrase is ‘born of the mind.’

(Williams 1980, 11)

Cinema has the capacity to efface the distinctions Williams describes. Visual music may not resemble the world of visible objects and events at all. Their interpretation as exemplars of a ‘mental reality’ brings even the most abstract animations within the domain of a realism ‘born of the mind’ – visual music makes the same metaphysical claims as abstract art generally. This audio-visual organisation is definitional for visual music and remains common in motion graphics. It is a ‘more true’ depiction than those dependent on ‘natural’ linkages such as ‘lip-sync’ to create an appearance of the everyday phenomenal world. In place of reproducing the audience’s everyday phenomenal encounter, visual music uses synchronisation to demonstrate the ‘reality’ of an unseen, spiritual world otherwise invisible to our senses. This excess of metaphysical meaning is the visual music heritage in both Ça Ce Soigne? and Scott Pilgrim vs. The World. The shift from the invocation of a phenomenal encounter to one constructed from ideological belief can be subtle: The fundamental links between synchronisation and realism are constants for commercial production, even when these connections are as simple as the alignment of spoken and written language. This transformation, an equally direct and automatic linkage as naturalistic synchronisation, returns the audible to the realm of signs, assigning particular meaning otherwise absent outside the motion picture.

From the very start of Kyle Cooper’s title sequence for Wimbledon (2004), synchronisation connects sound to typography, evoking naturalistic connection of sound to image comparable to ‘lip-sync’. However, although the sound of a tennis ball being hit with a racket has been synchronised to each credit’s appearance, it is an artificial relationship that creates a prosaic example of synaesthetic form: Typography does not make noise. The addition of live action shots later in the sequence depend on audience expectations to integrate this sound into the narrative space – to become a ‘diegetic’ element requires a recognition of what the sound in the visible space might be – the title sequence doesn’t show a tennis match being played. The shots focus on the spectators, judge and press – but the sound of playing the game is clearly heard. The editing and motion in each shot replaces the game with the text of the titles, a substitution that associates the subject of the film (the tennis Championships at Wimbledon) with the formal design of the credits.

Only the audience’s past experiences and knowledge can make this arrangement of typography-sound presented in the design coherent: This ‘more true’ depiction is the audience and other spectacle surrounding the tennis matches at the Wimbledon competition. It is an example of a realism ‘born of the mind’, shown by the association of hit ball with credit where the text on screen replaces the tennis match as the audience’s focus. What is going on – a ‘simple’ question – requires a complex answer that originates with established knowledge of the world that is invoked in the statement through the film title, ‘WIMBLEDON’, the distinctive sound of the tennis ball being hit in the tennis match itself and the various views of the surroundings of those games. This apparent ‘realism’ is an illusion, one that is assembled from fragments that are themselves partial, requiring established knowledge to interpret. That the audience makes these connections fluidly and without pause is what renders them ‘natural’. In the live action footage in the Wimbledon title sequence, connecting the sound to image is superficially direct – understanding the tennis match as a public spectacle requires a recognition of what is happening; it uses the mimetic identification of the sound to link the actions that are shown in the titles to the tennis match that is not shown. This convergence of abstract form with a realist meaning is a recurring aspect of how experimental animation has been transformed (Betancourt 2016) by the ‘avant-pop’ approach to become commercial entertainment. Motion graphics especially reveal this heritage in its consistent assertion of representational meanings for abstract graphics, as in the various needles in The Man With The Golden Arm, genetics in X-Men: First Class, orchestra and medical imagery of Ça Ce Soigne? and the transformation of direct animation into kinetic graffiti in Scott Pilgrim vs. The World.

Conclusion

Like experimental animation, motion graphics occupy a marginal position in relation to other histories of motion pictures – the important designers such as Saul Bass are rarely mentioned except in passing. Experimental animation and avant-garde film provide the historical sources for contemporary motion graphics, both in terms of morphology and as structural guides for the synchronisation of sound and image. At the same time, this commercialisation asserts the familiar dimensions of what was challenging – avant-garde images and techniques – making them familiar, mundane. This transformation of difficult, alienated Modernist imagery is as true of the white line-needles of Bass’ The Man With The Golden Arm as of the spirals in Clowes’ X-Men: First Class. It is a fundamental shift of meaning that unites these changes from experimental into commercial across the history of motion graphics as a field. This ‘normalisation’ is a distinguishing feature of McCafferty’s ‘avant-pop’, separating motion graphics from the historical avant-garde. The changed meaning of abstraction as a diagrammatic representation is thus a typical effect of the convergence with commercial production that neutralises the disruptive aspects of its experimental sources by subordinating their effect to the narrative demands of the film to which these otherwise potentially challenging designs are appended.

The pseudo-independence that intertextuality offers the title sequence enables the design to be simultaneously of the main narrative and distinct from it, a parallel construction with its own internal structure, themes and formal appearance. The acknowledgement of the visual music tradition in these designs brings their formal origins into consideration. By directing attention to the title design as a self-contained entity, this shift insists on an additional level of autonomous signification for both the title sequence and motion graphics more generally. The metaphorical connection of title design to the film it introduces rhetorically masks this pseudo-independence, while for instance the context of Kenworthy’s design announces it as belonging to a separate realm than the narrative. Music anticipates narrative. As with Saul Bass’s quotation-reference to Richter’s film Rhythmus 21 (Film ist Rhythmus) in The Man with the Golden Arm, the quotations apparent in Ça Ce Soigne? or Scott Pilgrim vs. The World provide intertextual associations that inform the interpretation of the film/title through these historical references, thus demonstrating the crucial (formative) mediation of experimental animation.

Notes

1 The designation of the German abstract and visual music animations as ‘absolute films’ began with the filmmakers themselves. The Novembergruppe exhibition of May 3, 1925 (a program which included Ruttmann, Richter and Eggeling’s films) was titled ‘Der Absolute Film’.

2 There are multiple sources for this history. See Tuchman, M. The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890–1985 (New York: Abbeville Press, 1985) or Brougher, K. Visual Music: Synaesthesia in Art and Music Since 1900 (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2005).

References

Allen, Irwin. The Time Tunnel. US, 1966–1967. Television series

Armstrong, Samuel, James Algar, Bill Roberts, Paul Satterfield, Ben Sharpsteen, David D. Hand, Hamilton Luske, Jim Handley, Ford Beebe, T. Hee, Norman Ferguson, Wilfred Jackson . Fantasia. US, 1940. Film.

Betancourt, M. Beyond Spatial Montage: Windowing, or the Cinematic Displacement of Time, Motion, and Space. New York: Routledge, 2016.

Betancourt, M. The History of Motion Graphics: From Avant-Garde to Industry in the United States. Rockville: Wildside Press, 2013.

Betancourt, M. Title Sequences as Paratexts: Narrative Anticipation and Recapitulation. New York: Routledge, 2018, 57–58.

Brougher, K. Visual Music: Synaesthesia in Art and Music Since 1900 .New York: Thames & Hudson, 2005.

Bute, Mary Ellen. Tarantella. US, 1940. Film

. Abstronic. US, 1952. Film.

Chouchan, Laurent. Ça Ce Soigne? (Is It Treatable?). France, 2008. Film.

Corra, B. ‘Abstract Cinema – Chromatic Music.’ In Futurist manifestos. New York: Art works, 2001.

Currie, H. and Porte, M., eds. Cinema Now. Cincinnati: University of Cincinnati Perspectives on American Underground Film, 1967.

Disney, W. ‘Adventure Land: The Title Makers.’ Walt Disney Presents, broadcast on ABC, 11 June, 1961.

Eco, U. ‘Interpreting Serials’. In The Limits of Interpretation. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 1994.

Elsaesser, Thomas. ‘Dada Cinema?’ In Dada and Surrealist Film. Edited by Rudolf E. Kuenzli, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1996.

Folkart, B. ‘Ron Hays; Multimedia Conceptualist.’ LA Times, 19 April 1991.

Geller, Bruce. Mission Impossible. US, 1966–1973. Television series.

Golden, William. The Visual Craft of William Golden. New York: George Braziller, 1962.

Hays, R. Report of Activities: June 1972 through January 1974, grant report to the Rockefeller Foundation and National Endowment for the Arts, 1974.

Hays, Ron. Space for Head and Hands. US, 1975. Film.

Hitchcock, Alfred. Vertigo. US, 1958. Film.

Huggins, Roy. Bus Stop. US, 1961–1962. Television series.

Jacobs, L. ‘Experimental Cinema in America 1921–1947.’ In The Rise of the American Film. New York: Teacher’s College Press, 1975.

Loncraine, Richard. Wimbledon. UK/US, 2004. Film.

Lukach, J. Hilla Rebay: In Search of the Spirit in Art. New York: George Braziller, 1983.

MacDonald, S. Art in Cinema: Documents Towards a History of the Film Society. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2010.

McCafferty, L. After Yesterday’s Crash: The Avant-Pop Anthology. New York: Penguin, 1995.

Moritz, W. ‘Jordan Belson: Last of the Great Masters.’ Animation Journal 7, no. 2 (1999): 4–16.

‘Pacific Title & Art Studio to be liquidated.’ Variety, 8 June, 2009, accessed 7 July, 2017. http://variety.com/2009/digital/markets-festivals/pacific-title-art-studio-to-be-liquidated-1118004696/

Potter, R. ‘New Scientific Tools for the Arts.’ The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 10, no. 2 (December 1951): 121–134.

Potter, R. ‘Sources of Stimulus: TV Commercials Often Draw on Avant-Garde Films. Art Direction 13, no. 9 (December 1961): 63.

Preminger, Otto. The Man With The Golden Arm. US, 1955. Film.

Richter, Hans. Rhythmus 21 (aka Film ist Rhythmus). Germany, 1921. Film.

. Film Ist Rhythmus. Germany, 1923. Film.

Robinson, Hubbell. Thriller. US, 1960–1962. Television series.

Sandhaus, L. Earthquakes, Mudslides, Fires & Riots: California & Graphic Design 1936–1986. New York: Metropolis Books, 2014, 158.

Saint-Saëns, Camille. Danse Macabre. 1874.

Schwartz, Sherwood. The Brady Bunch. US, 1969–1975. Television series.

Serling, Rod. The Twilight Zone. US, 1959–1964. Television series.

Spigel, L. ‘Back to the Drawing Board: Graphic design and the Visual Environment of Television at Midcentury. Cinema Journal 55, no. 4 (Summer 2016): 28–54.

Spigel, L., TV by Design: Modern Art and the Rise of Network Television. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Stanton, F. ‘Introduction.’ In The Visual Craft of William Golden. New York: George Braziller, 1962, 9.

Sutton, G. ‘Stan VanDerBeek: Collage Experience.’ In Stan VanDerBeek The Culture Intercom. Houston: Contemporary Arts Museum Houston/MIT List Visual Arts Center, 2011, 78–87.

Stevens, Leslie. The Outer Limits. US, 1963–1965. Television series.

Tuchman, M. The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890–1985. New York: Abbeville Press, 1985.

Vaughn, Matthew. X-Men: First Class. US/UK, 2011. Film

Weinberg, H. ‘30 Years of Experimental Film: Hans Richter Has Never Doubted the Validity of Pure Experiment.’ Films in Review 11, no. 10 (December 1951).

White, Maurice and Wayne Vaughn . ‘Let’s Groove’. New York: Columbia Records, 1981. Song.

Whitney, J. Digital Harmony: On the Complementarity of Music and Visual Art. Peterborough: Byte Books, 1980.

Wilder, Billy. The Seven Year Itch. US, 1955. Film.

Williams, C. Realism and the Cinema: A Reader. London: Routledge, 1980.

Wright, Edgar. Scott Pilgrim vs. the World. US/UK/Canada/Japan, 2010. Film.