Materiality, Experimental Process and Animated Identity

In a general analysis of experimental animation, three important (but frequently overlapping) concepts, materiality, process and identity, will be examined in this chapter.

As the term suggests, ‘experimental animation’ normally involves some form of experimentation – of testing and trying out new or alternative ways of animating. But traditionally the term ‘experimental animation’ has been somewhat difficult to pin down, probably due to its decidedly multifaceted nature. A particular animated work might be considered to be ‘experimental’ for a variety of discrete but often overlapping reasons: Its lack of traditional narrative; its lack of traditionally identifiable visual formations; its unconventional production techniques or use of materials; or even the manner in which it is presented to the viewer. Although many of these overlapping approaches to experimentation will be discussed, a primary focus of this chapter will be on experimental animation’s engagement with unconventional production techniques and its frequent (and unconventional) use of physical materials.

Frequently, but not always, it is the independent animator who most often engages in these experimental practices. Quite often this experimentation becomes unmistakably entwined with the animator’s own unique artistic vision. It is worth noting, however, that not all instances of experimental animation fall neatly into the realm of independent or auteur animation; examples can be found embedded within even the most large-scale commercial animated productions where innovation and experimentation will certainly occur.

As the authors Robert Russett and Cecile Starr have claimed, many experimental animators have also worked in the commercial animation industry, which they note

did not bring an end to experimental animation. New and exciting films have continued being made by the old and the young, in new styles, lengths, techniques and combinations of techniques.

(Russett and Starr 1988, 16)

An essential aspect of an experimental animation is the process by which it becomes animation, and how this becoming process can affect both the content and the aesthetics of the final animation.

Historically, many experimental animations have given prominence to the use of material substances, including: found-objects, three-dimensional puppets, paper cut-outs, sand, clay and oil paint. It is the use of such materials that have often helped to characterise experimental animation, differentiating it from the dominant cel animation productions. Compared to cel animation, these techniques usually afforded the individual artist a more immediate and considerably less expensive means of production. But it is from the use of these unique materials that a number of intriguing significations and interpretations have arisen, from which viewers have tended to interpret this imagery in rather diverse and, ultimately, quite extraordinary ways.

Although technologies have evolved dramatically in recent years, these concepts continue to be indispensable in the practice and the examination of experimental animation. This is particularly relevant when we consider both the inherent configurations of digital animation, as well as its ability to simulate many forms of traditional experimental animations.

Ultimately this chapter will consider concepts of materiality, process and identity which can be described as essential aspects of many experimental animations. It will argue that both the materials used and the processes employed in experimental animation are inherently complex and multilayered, and thus can have a simultaneously profound effect upon the form and reception of the final animation. These facets will be articulated through the application of relevant philosophical concepts that explore process and the complexity of material objects, as well as through a number of pertinent experimental animation examples.

Process and materiality

Although traditional cel animation is a material-based construct (being composed of layers of plastic sheets, ink and paint), historically it has generally sought to disguise its materiality and to project a very graphical and decidedly intangible image.1 By contrast, many forms of experimental animation have tended to celebrate their material basis, highlighting both how they were made and what they were made of. There are many different materials that can be used – in fact, just about any ‘thing’ can be animated. This section will survey some of the more common materials that have been explored in traditional experimental animation, including: pencil on paper animation, cut-out animation, found-object animation, abstract stop-motion animation and landscape animation. As will be described, distinct materials can also affect the aesthetics of the final film in unique ways. For example, if an animator chooses to work with predominantly malleable materials (such as clay, oil paint or sand) the resulting animation will be likely to contain a good deal of transformative movement and metamorphosis. From this brief survey of traditional techniques, there will be a further consideration of how some of these material-based techniques have been digitally simulated; and what relevance materiality might continue to have in contemporary experimental animation practice.

Cut-out animation is essentially a two-dimensional form of stop-motion animation involving the manipulation of characters and forms that have been constructed from ‘cut-out’ pieces of paper. This technique was strongly embraced by a number of experimental animators, independent animators and small studios (Lotte Reiniger, Jiří Trnka, Yuri Norstein) that found the technique to be both an accessible and a creative alternative medium with many advantages. Work that displayed highly detailed graphical imagery that was very expensive to achieve with traditional cel-animation, could be produced economically. Once the cut-out puppets were made, the actual animation could normally be produced in a matter of hours or days (rather than weeks or months). The characters, although somewhat limited in movement, would always ‘stay on model’ – something that was also challenging to achieve with the cel-animation technique. Plus, by using certain additional strategies, such as replacement animation in tandem with the manipulated cut-out puppet technique, a relatively fluid style of animation could be achieved.2 Although only marginally more dimensional than the materiality of cel-animation, cut-out animation does not normally attempt to hide its material nature, often appearing to showcase a greater amount of physicality than might actually be present.

Cut-out animation occupies a unique space between the graphical qualities of cel animation and the typical rigidity of puppet animation. Its super-flat two-dimensionality often makes changes in perspective and transformative movements difficult to achieve. But rather than a hindrance, this has often proved to be a remarkable area of experimentation. Whereas drawn animation can freely utilise the apparently limitless conventions of illustrative perspective and depth, cut-outs often have to employ alternative approaches and various deceits in order to achieve such shifting perspectives.

A number of animators have produced some intriguing films that have tested these boundaries of cut-out animation’s materiality, finding alternative movement-strategies within the limitations of the medium’s super-flatness. For example, Michel Ocelot has utilised intricate cut-out forms and characters that will occasionally break through into the third-dimension in unexpected ways. In Les Trois Inventeurs (1980) we see a 2D cut-out character rowing a craft through the air; in the midst of a rowing cycle, the oar can be seen physically to protrude outwards (towards the camera), producing an unexpected dimensional shadow effect that traverses the rest of the imagery. Another noteworthy cut-out animation is Amy Lockhart’s The Collagist (2009). This animation features both traditional hinged puppet forms (in the shape of human hands), as well as a great deal of very free-flowing animation that was made by sequentially replacing gradually evolving cut-out forms. Thus, the rigidity of the traditionally jointed cut-out ‘human’ hands contrasts with the refreshingly fluid and amorphous formations of pouring coffee, billowing smoke and blazing flames (see Figure 4.1).

FIGURE 4.1 The Collagist, Amy Lockhart 2009.

Pencil on paper animation has been a traditional technique generally used by many independent animators. For example, the work of Raimund Krumme, Joanna Priestley, Stuart Hilton and Robert Breer, have all expressly featured graphite lines of either grey or coloured pencils on paper. The initial advantage of this technique was that it did not require the extremely costly and time-consuming use of cels; yet it still provided a strong graphical aesthetic. However, most pencil on paper animations have also featured rather frenetic animated line-work which stems from the inevitable variations of line quality, the texture of the paper, and even the occasional smudge marks of the graphite. Quite often this technique will intentionally feature ‘boiling’ lines – an animated effect derived from tracing the lines of previous drawings. Normally this process is used as an economical means of adding ‘life’ to a pencil-drawn animation. Therefore, instead of having to actually animate the character into moving (that is, to redraw it in a substantially different pose each time) the animator can simply make an almost (but not quite) exact copy of it. The resulting boiling image presents a form that is ceaselessly in flux, but at the same time, its movement is limited to the quivering outlines and shaded textures so that it invariably foregrounds the graphite materiality of the image (Torre, D. 2015a, 149–51).

Found-object animation normally involves the animation of objects that are employed as they are: They have not been modified for their role in the animated film. They have been selected (rather than constructed), their selection being based upon their intrinsic form, colour and texture. Found-object animation has in recent years enjoyed a surge in popularity amongst animators such as PES, Kirsten Lepore and Max Hattler. This is probably due to the fact that it can be a very immediate form of animation (you don’t really need to draw or build anything). Also, there is an inherent authenticity to it that often testifies to the fact that it unquestionably involves the animation of real things without a lot of unnecessary digital intervention. Found-objects can be practically anything – from a rusty nail, to a teacup, to a child’s toy doll. According to Maureen Furniss, ‘Found materials include everyday items that create a sense of ordinary spaces, which can become extraordinary through the powers of animated motion’ (Furniss 2008, 258). Paul Wells describes object animation as embodying the idea of ‘fabrication’, which includes the ‘taken-for-granted constituent elements of the everyday world’, which is ‘in a certain sense [ … ] the reanimation of materiality for narrative purposes’ (Wells 1998, 91). So, for example, in the Quay Brothers’ animation Street of Crocodiles (1986) we see commonplace objects – screws, tools, glasses and wire – moving about within the construct of elaborately crafted sets. Here the objects are clearly ‘on stage’ and although they are ordinary, everyday items, they are engaged in a definite performance. According to Wells:

the Quay Brothers essentially animate apparently still and enigmatic environments which are provoked into life by the revelation of their conditions of existence as they have been determined by their evolution and past use. This gives such environments a supernatural quality, where orthodox codes of narration are negated and emerge from the viewer’s personal reclamation of meaning.

(Wells 1998, 91)

It is this animated performance by ordinary objects, set against an extra-ordinary background, that conveys the Quay Brothers’ celebrated surreal and supernatural effect.

There is a sequence in Jan Švankmajer’s stop-motion film, Dimensions of Dialogue (1982), that uses a number of found-objects. The sequence involves two large, human shaped, clay heads that sit on a table-top. These animated heads are engaged in a sort of confrontation as they glare at each other and project from their mouths a series of increasingly ridiculous ‘found-objects’. We know that the human-shaped heads are not real (and are merely constructed out of clay), but we do seem to empathise with them as being human. Yet, part of the strangeness and the humour of this sequence relies upon our clearly recognising the objects which protrude from the figures’ mouths as being everyday real objects. When each of the ‘real objects’ with a specific identity (the knife, the shoe and the pencil) protrudes, we identify in part with how these objects might feel in our own mouths. So, just as we might commonly empathize with a human character, we also identify with recognisable real-life objects when they are made to interact with ‘us’ in extraordinary ways. Ultimately, there is often a very visceral reaction to the witnessing of real (and what we perceive to be real-life) objects, animated and moving about.

Landscape animation (or environmental animation) is a large-scale form of animation, often set within a real-world landscape (or cityscape), in which the animator will normally work with both found-objects and with found-spaces to create site-specific animations. In landscape animation, rather than relying on a more allegorical definition of place (such as a small-scale stop-motion set or a painted background to reference a particular place), the animation is produced directly within the real world. This particular approach to animation is greatly influenced by the location and by the natural materials found at the site. Some notable examples of experimental landscape animation include: Rippled (Darcy Prendergast 2011), Earth Shiver (John ‘Hobart’ Hughes 2006), Bottle (Kirsten Lepore 2011) and Land (Eric Leiser 2012).

Much of the work of landscape animator Eric Leiser involves a controlled manipulation of his natural surroundings. There are extensive sections in his film, Land, that involve simply the reconfiguration of found-leaves and sticks into choreographed patterns and evolving geometric forms. In other portions of the film Leiser highlights the various forms within the landscape through the introduction and manipulation of brightly coloured animated ribbons. Later, snow is trampled upon over large hillsides, and on large empty beaches lines appear and large abstract designs are drawn into the sand.

Because of the open spaces of landscape animation, the process of animating will often be made highly visible. For example, animations that are created on sand, grass or snow might highlight the unintentional footprints of the animators as they engage with the elements ‘frame-by-frame’. These ‘accidents’ become an important part of the aesthetic of the animation. Furthermore, these also serve to authenticate the animation – proving to the viewer that it was indeed shot on a grand scale, and in the real world without any digital interventions (Torre, D. 2017, 220–230).

Digital simulations of materiality

Although many animators continue to work with material objects in their animation practice, there is also the capacity for digital animation to reference – and simulate – many of these traditionally material-based forms of experimental animation. Quite often, however, the digital simulation of a particular animation technique, rather than simplifying the process, can actually involve a series of very complex procedures. What might have been an incredibly easy and low-cost approach in traditional filmmaking, can become quite the opposite in the digital realm. This translation of materials and techniques might further complicate the definition of experimental animation, and while on one hand it might merely exhibit an experimental aesthetic, it also potentially allows for a type of technical experimentation within the animated form.

One notable early example of a simulated pencil on paper animation technique can be found in Eric Darnell’s Gas Planet (1991). It is actually a 3D digital animation that employs a simulated pencil texture which is overlaid onto the dimensional digital forms. In contrast to the rather simple intuitive process of shading a drawing with a coloured pencil, this production involved a rather complex and multi-staged process of applying an animated texture map to the 3D forms.

Stop-motion clay animation is another technique that has been digitally simulated. One particularly striking example can be found in a series of promotional advertisements that were produced for the Nickelodeon television network (Plenty Studio, 2013). These ads, made entirely with 3D digital techniques, feature very fluid formations (and transformations) of figures that were made to look as if they were constructed from plasticine, and then animated using a traditional stop-motion technique. They showcase an array of brightly coloured orange ‘plasticine’ forms which were made to continually transform from one outlandish character to another (such as from a guitar-playing-chicken to a cheerleading-zebra) and then finally culminate into the ‘Nick’ logo. Although plasticine generally lends itself towards very fluid types of metamorphosis, a modelled and rigged 3D form would strongly resist such manipulations. In fact, an animator would probably end up ‘breaking’ the digital model if he or she tried to manipulate it in this way. Thus, in order to create the very fluid metamorphic effect of animated plasticine the production team at Plenty Studios constructed hundreds of individual digital models, each slightly different from the previous. These were then sequentially replaced, one at a time and frame-by-frame, within the digital scene. Instead of gradually manipulating a single plasticine form, a digital version of the replacement animation technique was used. In addition, each model was digitally coated with a ‘plasticine texture’, complete with ‘fingerprints’, in order to further simulate the hand-made quality of traditional clay animation.

Perhaps the most prominent (and arguably the most expensive) simulation of a traditional material-based animation technique can be found in the commercial animated series, South Park (1997–present). The original pilot for the series was created in the traditional manner using characters made from cut-out pieces of paper and animated frame-by-frame under the camera. However, the subsequent long running series (1997–present), as well as the feature film, South Park: Bigger, Longer and Uncut (Trey Parker, 1999), were made using state-of-the-art computers and 3D software. Traditionally, cut-out animation has been regarded as one of the most inexpensive ways to make an animated film; yet with the initial set up of the South Park studios, large sums of money were spent on computers and software simply in order to commence production on a simulated cut-out animated series (Dan Torre, one of the authors of this chapter, worked as an animator on the South Park feature, South Park: Bigger, Longer and Uncut (Trey Parker 1999)).3 In the mid-1990s, a meticulous simulated version of the cut-out technique was still a rather untried concept, and the translating of this technique into the digital realm did represent a form of technical experimentation. In those early days of digital animation, the most intuitive way of working within 3D was to exploit the technique’s highly dimensional and super-smooth motion qualities, which was in strong contrast to the fundamental aesthetics of cut-out animation. However, as the South Park series has continued, it has progressively embraced its digital materiality (using more and more overtly digital-produced effects) in parallel with its simulation of paper cut-outs – creating a hybrid animation aesthetic.

Arguably, these digital simulations of what would normally have been considered a hallmark of experimental animation can represent an intriguing and dichotomous process. On one hand, when animators employ digital tools to simulate the experimental manipulation of materiality they might be engaged in a simple mimicry of experimental materiality, but on the other hand they also might be engaged in an experimental manipulation of digitality. Depending upon processes used and the context of the animation, either mimicry or an experimental nature might be underscored.

Ephemeral materiality

All animation is, at least to some degree, ephemeral; it is only visible for the fleeting moments that it is presented to us. Yet, to the experimental animator, who may be deeply involved in the overt manipulation of real-world materials, this can be seen as an intriguingly dialectical space for experimentation. And a number of animators have experimented with these alternating concepts of materiality and of ephemerality in quite innovative ways.

For example, Alexandre Alexeieff and Claire Parker (who are best known for their pin-screen animations) also made animated films that featured a distinctive technique, which they referred to as a ‘totalization of illusory solids’, which was ‘a sort of metamorphosis of a movement into an object’ (Russett and Starr 1988, 95–96). They made a number of experimental tests of this technique; one of which became the logo for the French film studio, Cocinore. These animated films were made by moving an object (such as a handful of sticks) quickly back and forth in front of a camera while a photo was taken. Because the camera would be set to a very slow shutter speed, the resulting image would be of a large streak or blur. When sequentially shot, frame-by-frame as animation, these ephemeral streaks would appear as an animated ‘solid’ (yet amorphous) form.

An inverted variant of this concept can be found in the technique known as light-drawn animation, which involves the ‘solidifying’ of light into apparently material forms. Some of the most intriguing results can be found in Darcy Prendergast’s films, Lucky (2009) and Rippled (2011). Similar to the ‘illusory solids’ technique, these animations require long-exposure photographs in order to create forms that are composed of streaks and blurs. However, whereas the previous technique by Alexeieff and Parker essentially involved the multi-stage conversion of solid objects into ephemeral streaks and finally manifesting as amorphous solids; light-drawn animation condenses ephemeral light into apparently material forms (see Figure 4.2). One of the unique strategies that Prendergast used in order to ‘register’ his light-drawings from one frame to the next was the construction of a thin wire ‘stencil’ that the animators would trace around with their light-torch. If the light-character was required to move, the wire stencil would be bent, adjusted and moved into the next required shape. This new wire form would then be traced with the light in order to create the next frame of animation. Because of the slow-shutter speed, neither the animator that drew the image, nor the guiding wire stencil are visible in the final animation – only the ‘materialised’ streaks of light (and the extant background settings) will be observable (Torre, D. 2017, 53).

FIGURE 4.2 Rippled, Darcy Prendergast 2011.

Raimund Krumme has utilized the extensive ‘empty white-space’ of pencil-on-paper animation to his creative advantage. His films generally feature rather anonymous-looking characters, that seem to be forever walking around and exploring his ever-shifting spaces. Although the white space surrounding his line-work drawings appear devoid of all imagery, he is able to imbue it with alternating connotations of materiality and context. And though there has been a long tradition of subverting form and space in animation, Krumme is able to do this most effectively through his determined use of very simple lines drawn upon white paper. Thus, he is able to creatively explore not only a fluidity of the visible forms, but also of the entirety of the surrounding white spaces. For example, in both Crossroads (1991) and Rope Dance (1986) we see characters that are continually being flummoxed by the ever-shifting material connotations of simple line-work shapes. At one moment, a rectangle might act as a passageway into another space, but then suddenly become a solid wall, then suddenly gravity might be reversed, and it will become a pitfall trap, sucking the character downwards. And although the actual form (the simple line-work rectangle) will not change in physical appearance, its changing impact upon the animated characters will be extreme. The limiting of the mise-en-scène to the simplicity of the white paper, instead of inflicting any actual limitation, in fact provides an infinite space in which to experiment with the material (and immaterial) nature of animation.

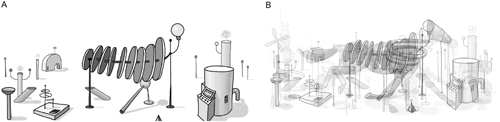

Dana Sink’s short animation, Power (2016), is a particularly interesting digital animation that also involves a sparsely drawn line-work image that is set within a surrounding white space. This animation also experiments with the idea of ephemeral white space, but in addition it experiments with the fundamental nature of the animation effect. The animation consists of approximately 20 different cyclical scenes, each featuring a different mechanical apparatus. Initially each scene is shown for several seconds, allowing for the cycle of the mechanical device ‘in action’ to play out a few times before the next cyclical scene is presented. After each of the 20 unique cyclical scenes are shown, all 20 scenes are presented again, but this time each of the scenes is displayed for a shorter duration. This strategy is repeated several times, until ultimately each scene is visible for only a single frame (1/24th of a second). The final result, then, is a twenty-frame meta-cycle that is composed of a single-frame from each of the original cyclical scenes. Remarkably, this cumulative aggregate (or ‘meta-cycle’) manifests itself not as a machine, but instead as a cyclical Muybridge-style representation of a running horse.

Thus, out of 20 rather nonsensical sequences, arises a new cohesive (yet quite ephemeral) entity of a running horse. However, each individual frame of this meta-cycle, in and of itself, does not portray a fully visible single frame of a running horse. In fact, each individual frame continues to look like a nonsensical mechanical device. It is only when we watch it in motion that it suggests a ‘running horse’. It actually requires at least three consecutive frames of this ‘meta-cycle’ to provide the viewer with a substantial enough ‘persistence of vision’ effect to be read as a horse form. In other words, if one were to take at least three of these frames and overlay them on top of each other (with their opacity reduced) only then would they produce a clearly identifiable image of a horse in mid-stride (see Figure 4.3).

FIGURE 4.3 Frame grabs from Power, Dana Sink 2016. Image A depicts a single-frame from the animation, image B is an overlay composite of several consecutive frames from the animation, which simulates the ‘animation effect’ that is generated when one watches the animation.

Some 45 years earlier, experimental animator Jules Engel created an animation entitled, Accident (1973). It also featured a simple, pencil on paper, animated cycle (that was also derived from Muybridge). Engel’s animation featured a cycle of a running dog, which was made to repeat dozens of times. However, when filming the animation under the camera, Engel progressively erased his animated image (frame-by-frame) throughout each iteration of the filmed cycle. Thus, the film begins with a very distinct animated visual of a running dog, and progressively becomes more and more ephemeral, until there is virtually nothing left but a slight flickering smudge. But what does remain, is our memory of the iconic Muybridge-styled dog running. And it is this memory, which provides us with an ostensibly persistent form of an illusionary solid.

An animation technique that seems to be growing widely in popularity involves the use of 3D printed characters. These 3D printed figures are then used as elements in stop-motion animations. Conceptually, this technique involves a similar idea to light-stick animation – in that it necessitates the concretising of an ephemeral form – however, rather than a streak of light, it involves the concretizing of a digital animation. One notable example can be found in the animated short, Bears on Stairs (DBLG 2014). This animation was created by printing out each frame of a 50-frame walk cycle of a bear climbing a flight of stairs. These printed objects were then placed (and replaced) one by one in front of a camera to create a material-based stop-motion animation. The result is a 3D digital walk cycle which has been concretised into real world spaces – effectively creating a materialistic simulation of a 3D digital animation. And because each and every frame of the digital animation was made into a stop-motion object, the resulting stop-motion animation displays an extremely fluid motion. However, not only do we see an incredibly fluid movement, we also are able to see the rather spline-y ‘material’ aesthetic of the 3D animation.

Material identity

As discussed earlier, many experimental animations have highlighted the use of materials, and this is perhaps most evident in animations that employ found-objects. Found-object animation tends to feature immediately recognizable forms, such as toothbrushes, teacups or shoes. Yet, when these objects are recontextualised and made to move in novel ways, then we might begin to question their identity. In The Social Life of Things, Arjun Appadurai argues that things assume meaning primarily according to how they are used, ‘from a methodological point of view it is the things-in-motion that illuminate their human and social context’ (Appadurai 1986, 5). Therefore, it makes sense that we might be able to alter an object’s projected identity through the use of animation.

The animator known as PES quite often uses found-objects in decidedly metaphorical ways. In his short, Western Spaghetti (2009), a number of household items are used in lieu of food ingredients to animate the creation of an Italian dinner. Pincushions are used as tomatoes, and are made to mash down just as a real tomato would. Pads of yellow paper are sliced as a stick of butter might be, and little sugar candies (candy corns) are used to create the flickering flames on the stovetop. The manner in which these objects move is very convincing – and although all the while we know that the pieces of string are not really grated cheese, and that the rubber bands are not pasta noodles – we still can delight in their remarkable embodiment and visual punnery. Similarly, in the animated short, The Deep (2010), we see a number of ordinary tools and kitchen utensils made to behave exactly like fish and other underwater creatures. Lengths of chain become waving strands of seaweed, and old keys become darting schools of fish. And in one scene we see multiple measuring devices (calipers) that are, through the process of replacement animation, made to move and swell up just like jellyfish. And although these objects simulate these new roles convincingly (and these roles are further amplified by an underwater themed audio track), we are still very aware that these are found-objects, and their original identity implicitly remains.

Material objects in an animation production are well placed to provide the viewer with a deep complexity of phenomenological meanings. And, as noted above, a good deal of this complexity will stem from the addition of animated movement and context; however, much of it can also be seen to originate from the actual physical objects. According to Graham Harman, objects are inherently very complex entities:

objects themselves, far from the insipid physical bulks that one imagines, are already aflame with ambiguity, torn by vibrations and insurgencies equaling those found in the most tortured human moods.

(Harman 2002, 19)

Although the viewer will likely project their own cognitive complexities, the phenomenological experience of the object is ultimately dependent upon its physical existence. Similar to human actors, objects are fundamentally full of complexities and uncertainties – and it is because of this pre-existing condition that objects are capable of presenting and assuming a wide-range of alternate personas. And it is because of this surprising complexity that we are so readily able to accept new meanings and new identities when we watch animated found-objects (Torre, L. 2017, 4).

According to Martin Heidegger, when an object contains multiple identifiable states, it can be classified as a ‘ready-to-hand’ object (as opposed to the more diminutive, ‘present-at-hand’ object). A ‘ready-to-hand’ object is one possessing an identity familiar to us on account of its usefulness and its complex interconnectedness to the rest of our worldly experience. In relation to an object such as a hammer, Heidegger proposes:

the more actively we use it, the more original our relation to it becomes and the more undisguisedly it is encountered as what it is, as a useful thing. The act of hammering itself discovers the specific ‘handiness’ of the hammer.

(Heidegger 1962, 70)

Thus, a teacup is known and understood by us because we can pour tea into it: It holds tea, we can drink from it and we can hold it in our hands when we take a drink. However, ‘present-at-hand’ objects would be things that we generally have no need to consider for their individual identity – the anonymous clutter on a shelf for example: it is ‘present’, but not really of ready use to us.

Heidegger argues that it is quite possible to imbue this apparently useless bric-a-brac with greater context and usefulness; however, if we try to do so, it will usually require us conceptually to distort the objects in a rather artificial manner (Heidegger 1962, 70–72). Perhaps, for example, it would require us to take the anonymous pile of bricks in the corner and use them to build something useful – like a bench to sit on. Similarly, we could argue that the act of animating a found-object can immediately elevate it to a resemblance of a ‘ready-to-hand’ object. Its resulting ‘life-like’ movement and context will imbue it with a good deal more than just a ‘present-at-hand’ understanding. However, even though this might be quite an effective method by which to elevate objects to a higher level of meaning – stop-motion animation does represent a rather artificial means of doing so. Paul Wells seems to echo this when he states that animated found-objects are ‘Simultaneously [ … ] both alien and familiar; familiarity is a mark of associational security while alienation emerges from the displacement of use and context’ (Wells 1998, 91).

Heidegger asserts that the opposite is also conceivable, that is, it is possible to strip or reduce a ready-at-hand object (such as a useful teacup) into the realm of present-at-hand objects (for example, the anonymous clutter on a shelf). His reasoning for doing this is so that we might gain a better understanding of the materials of our world that we generally ignore (a sort of vicarious means by which to empathise with that which we do not understand). Thus, if we look at a hammer, we can at least momentarily disregard the fact that it is a useful tool for hammering in nails, and instead focus solely upon its colour, shape and material construction (wood, metal or other material). As a result, we might discover that many of the things that surround us, which we take for granted, are actually of a similar fundamental nature (they are also all composed of wood and metal, etc.).

This is exactly what is required of us when we look at an abstract image or animation; we are compelled to focus upon, not merely the form’s real-world context, but instead upon its more elementary qualities. Lambert Wiesing has defined the general idea of abstraction as being primarily about the reduction of associations and context:

Something is abstract if it does not bear any relation to visible, concrete objects. Abstraction, then, is a disregard of a discernible association to an object.

(Wiesing 2010, 63)

A number of other philosophers (including Alfred North Whitehead, Nicholas Rescher and Gilles Deleuze) have also suggested that decontextualisation is one of the integral aspects to the idea of abstraction. That is, if something or some process can be stripped of its context, then it is no longer bound to any particular place or time and can then be infinitely repeated. Whitehead (and later Rescher) referred to colours and shapes as being ‘eternal objects’, in that they could quite easily be stripped of their context and could then be infinitely repeated without any regard to historical time or place (Rescher 2006, 52).

In recent years, there have been a number of experimental animations that could best be described as ‘abstract stop-motion’. These films tend to utilise real-world objects to create non-representational sequences that are much more similar to abstract motion graphics than to traditional forms of stop-motion (Wallace and Gromit, Gumby). Initially, the concepts of abstraction and stop-motion can seem quite divergent and are not intuitively linked in most people’s minds. We tend to think of abstraction as being primarily about shape, line and colour, while we think of stop-motion as being primarily about the movement of puppets and other recognisable things that have clearly identifiable features.

Yet, it is possible to ‘reduce’ any identifiable object to one that is much less identifiable (and therefore much more abstract). Abstract stop-motion animation essentially seeks to do this, to strip identifiable ‘things’ of their associated ‘identities’ and thereby transform them into components of abstraction. There are some fundamental animation strategies that one can use in order to transform ‘things’ into the realm of the abstract. These strategies usually involve the:

1. destabilisation of forms, and the

2. repetition of forms.

As a result, the viewer will be encouraged to focus primarily on the indeterminate qualities of shape, colour and movement. The first approach (destabilisation of forms) can comprise such things as flickering, metamorphosis, the splintering of forms or the coalescing of smaller objects into larger forms. Such disrupting movement will tend to shift the emphasis away from a particular form or a recognisable character and instead highlight its constituent abstract qualities. The second approach (repetition of forms) might involve a choreographed manipulation and repetitions of similar objects. Thus, these repetitive forms will no longer represent the specific identity of an object, but rather a larger amorphous collective. In this way, even the most recognisable forms can be transformed into apparently abstract animations.

One recent experimental film that employs these approaches in the animation of real world found-objects is Max Hattler’s AANAATT (2008). This animation was shot on a mirrored coffee table in a lounge room using natural light and it features all manner of objects, mostly old mechanical spare parts and building materials. Because of his use of replacement animation (in this instance, the subsequent ‘replacing’ of marginally different paper cut-out forms, one after the other, in a frame-by-frame manner, in order to create a more fluid animation aesthetic), the forms all appear very unstable. They seem to grow and transform, sometimes to break apart into many constituent parts and sometimes reform into larger structures. Hattler also employs the use of flicker where he placed an object in frame for one exposure, then removed it from the frame for the next exposure and placed it back into the frame for the next – effectively destabilising the identifiable form into a flickering transience. Additionally, many of these elements were choreographed into a continuous patterned array. Thus, rather than one single cone shape, dozens of them were made to move about together – creating an ambiguous congregating mass (Torre, D. 2015b). Similarly, Jonathan Chong’s animated music video Against the Grain (2012) is a stop-motion animation made almost entirely from office supplies and wooden pencils. But because of his heavy use of the repetition of forms, the film becomes not really about a wooden pencil object, but primarily about the shapes, colours and motion-patterns of the moving imagery. As these pencil forms are subsequently duplicated, they lose their individual identity and become complex patterns of repetitive imagery and movement.

By deliberately stripping objects of their identity, the animator can express an intriguing dialectical aesthetic of identity and abstract anonymity. Of course, the viewer can still identify that an abstract stop-motion film might be composed of recognisable real-world objects; but its primary identity will be one of abstraction. Similarly, when the animator PES imbues his found-objects with a staunchly alternate identity of, for example, a jellyfish, we are still able to comprehend the underlying tool-object as well.

Conclusion

Nearly all animation is arguably ‘an experimentation of movement’, in which the animator attempts, through numerous means, to make inanimate forms move. Until recent decades, animation was, for the most part, inescapably a very expensive and time-consuming process – thus, individual artists would often turn to unconventional materials and processes in order to make animation into a more accessible practice. Others, already steeped in the material arts of, for example, painting and sculpture, would seek to extend their work into the animated realm. Still others, perhaps in the midst of industry, would seek to discover new production processes and new kinds of imagery that they might utilize. Whatever the motivation, it was from these pivots towards new materials and new processes that a great deal of uniquely experimental animated films have emerged.

This chapter has explored what are arguably three of the most essential concepts that stem from these animated experimentations: The overlapping ideas of materiality, process and identity. It is from these experimentations with materiality (both actual and simulated), and the many diverse processes that can be employed in the production of animation, that we are able to experience some profoundly distinctive visuals. As technology evolves there will likely be progressive changes in the way we go about animating, yet, the underlying concepts of materiality, process and identity are likely to persist, and continue to provide us with vibrant spaces for experimentation.

Notes

1 For more on the materiality of cel animation see Hannah Frank’s essay ‘Traces of the World: Cel Animation and Photography’ (2016, 23–39).

2 In this instance, the subsequent ‘replacing’ of marginally different paper cut-out forms, one after the other, in a frame-by-frame manner, in order to create a more fluid animation aesthetic.

3 Dan Torre, one of the authors of this chapter, worked as an animator on the South Park feature, South Park: Bigger, Longer and Uncut (Trey Parker 1999).

References

Appadurai, Arjun. The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Darnell, Eric. Gas Planet. US, 1991. Film.

DBLG. Bears on Stairs. UK, 2014. Film.

Engel, Jules. Accident. US, 1973. Film.

Frank, Hannah. ‘Traces of the World: Cel Animation and Photography.’ Animation: An Interdisciplinary Journal 11 no.1 (2016): 23–39.

Furniss, Maureen. The Animation Bible. New York: Abrams, 2008.

Harman, Graham. Tool-Being: Heidegger and the Metaphysics of Objects. Chicago: Open Court, 2002.

Hattler, Max. AANAATT. Germany, 2008. Film.

Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time. New York: Blackwell Publishing, 1962.

Hughes, John. Earth Shiver. Australia, 2006. Film.

Krumme, Raimund. Rope Dance. Germany, 1986. Film.

Krumme, Raimund. Crossroads. Germany, 1991. Film.

Leiser, Eric. Land. US, 2012. Film.

Lepore, Kirsten. Bottle. US, 2011. Film.

Lockhart, Amy. The Collagist. Canada, 2009. Film.

Ocelot, Michel. Les Trois Inventeurs. France, 1980. Film.

Parker, Trey and Matt Stone . South Park. US, 1997–present. TV series.

Parker, Trey and Matt Stone . South Park: Bigger, Longer and Uncut. US, 1999. Film.

PES. Western Spaghetti. US, 2009. Film.

PES. The Deep. US, 2010. Film.

Prendergast, Darcy. Lucky. Australia, 2009. Film.

Prendergast, Darcy. Rippled. Australia, 2011. Film.

Quay, Stephen and Timothy. Street of Crocodiles. UK, 1996. Film.

Rescher, Nicholas. Process Philosophical Deliberations. Frankfurt: Ontos Verlag,, 2006.

Russett, Robert and Cecile Starr . Experimental Animation – Origins of a New Art, Revised edition. New York: A Da Capo Paperback, 1988.

Sink, Dana. Power. US, 2016. Film.

Švankmajer, Jan. Dimensions of Dialogue. Czechoslovakia, 1982. Film.

Torre, Dan. ‘Boiling Lines and Lightning Sketches: Process and the Animated Drawing.’ Animation: An Interdisciplinary Journal 10, no. 2 (2015a): 141–153.

Torre, Dan. ‘Persistent Abstraction: The Animated Works of Max Hattler.’ Senses of Cinema, no. 76, 2015b.

Torre, Dan. Animation – Process, Cognition and Actuality. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

Torre, Lienors. ‘Persona, Celebrity, and the Animated Object.’ Animation Studies Online Journal 12, (2017): 1–6.

Wells, Paul. Understanding Animation. London: Routledge, 1998.

Wiesing, Lambert. Artificial Presence: Philosophical Studies in Image Theory. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2010.