Deciphering narrative in Lewis Klahr’s The Pettifogger (2011)

Lilly Husbands

The historical marginalisation of experimental animation within scholarly discourse has resulted in a lack of examination of the formal and narrative complexities that have manifested in experimental animations, particularly since the last quarter of the twentieth century.1 Animation as a technical process offers artists extraordinary potential for formal experimentation and expressive freedom, where the conceptual and aesthetic concerns of visual and graphic arts are combined with the duration and motion of cinema. Individual animators’ explorations of this freedom in their creative processes have generated works that express many different aesthetic, formal and conceptual agendas (sometimes within a single animation). Experimental animators tend to reject or subvert mainstream storytelling conventions, and their alternative techniques and expressive modes invite us, in the words of Robert Russett and Cecile Starr (1988), to ‘develop new standards of judgment and [ … ] even new aesthetic attitudes’ (11). This unconventionality makes it beneficial to engage with them on their own terms. Yet, despite an increased output of scholarly studies of animation and experimental cinema over the last 20 years, experimental animations rarely receive the kind of in-depth analyses that their formal and conceptual intricacies demand.

Examining experimental animations in their specificity is a particularly productive way of approaching the art form, and a rich multitude of insights and interpretations can arise from submitting them to close analysis. This is especially true in terms of understanding the complex ways that experimental animators have engaged with narrative in their works. Experimental animation’s historical rootedness in modernist abstraction has attached to it connotations of non-objectivity and non-narrativity which, while not entirely inaccurate as generalisations, fail to acknowledge the wide range of engagements with narrative that can be seen across its long history.2 Experimental animations such as Harry Smith’s Heaven and Earth Magic (1957–62), Suzan Pitt’s Asparagus (1979), Larry Jordan’s Sophie’s Place (1986), Run Wrake’s Jukebox (1994), Janie Geiser’s Ghost Algebra (2009) and James Lowne’s Our Relationships Will Become Radiant (2011) – to name but a few – exhibit narrative elements such as goal-orientated protagonists and causally linked events unfolding across relatively coherent times and spaces (Bordwell and Thompson 2012, 73). However, the precise significance of these elements (characters’ actions and motivations, connections between and identity of locations) often remains opaque, and animation’s capacity for fantastical or imaginative visualisation is often used in complex and mystifying ways that complicate any straightforward understanding of a work.

In this chapter, I hope to demonstrate the benefits of giving experimental animations their due attention by offering a close reading of Lewis Klahr’s enigmatic and polyvalent feature-length collage animation The Pettifogger (2011). Since the beginning of his career in New York in the late 1970s, Klahr’s films and collage animations have circulated within the interconnected worlds of avant-garde cinema, experimental animation and, more recently, gallery installation.3 One of the most prolific and well-known contemporary American collage filmmakers, Klahr’s work blends structures and modes of engagement found in classic Hollywood narrative with poetic modes of expression that are germane to avant-garde cinema. As an artist Klahr aligns himself directly with the traditions of experimental filmmaking, citing avant-garde filmmakers such as Kenneth Anger, Bruce Conner, Ken Jacobs and Jack Smith as influences (Klahr 2005, 234). In particular, he shares with these filmmakers an affinity for subversive engagements with classic Hollywood storytelling conventions and an allusive, elliptical approach to structure and composition. As I will demonstrate, understanding Klahr as an avant-garde filmmaker provides essential clues for interpreting the complex visual language of his imagery. However, the ways he combines mimetic representation, abstract imagery and actual objects are unique to the graphic characteristics of collage animation. As animations, his works expand upon classic Hollywood and avant-garde cinema traditions and techniques in inventive ways.

Narrative as hermeneutic in experimental animation

In general, experimental animations tend to defy univocality and actively resist straightforward interpretation. Their indeterminacy is one of their most stimulating and productive aspects because it invites the viewer to actively participate in their comprehension of the animation. Rather than coming across as vague or confused, indeterminacy in experimental works is often what immediately piques our curiosity, urging us to discover all the various ways of understanding them. One of the most instinctive ways we seek to comprehend a work (particularly when characters are present) is by searching for some semblance of narrative structure. When narrative is understood as an experiential element of spectatorship – as cognitive process, as a means of interpretation, as hermeneutic – the very possibility of ‘pure’ non-narrativity comes into question.

This way of thinking is aligned with cognitive approaches to avant-garde cinema developed by scholars such as James Peterson, Noël Carroll and Paul Taberham. Taberham (2018) has noted that in a cognitive context narrative can be understood as both a text structure and also a mode of comprehension, where the former informs and activates the latter. Peterson (1996) has argued that avant-garde film viewing is a kind of problem solving. He suggests that over the course of a given film, viewers apply various heuristics in the form of educated guesses, intuitive judgements, categorisation or common sense, noting that viewers often draw more or less explicitly from their knowledge of the world in order to integrate a ‘film’s details into a coherent, though not necessarily highly unified, whole’ (Peterson 1994, 31). With these ideas in mind, my analysis of The Pettifogger serves as an illustration of some of the ways that experimental animations invite viewers to exercise their powers of perception, cognition and interpretation.

Collage animation is one of the forms of experimental animation that historically has been discussed in narrative terms.4 Commonly comprised of a combination of printed and photographic materials, a single image in a collage animation has potentially numerous ways of interconnecting with the images that surround it – both spatially and temporally – and therefore is able to operate on multiple levels of communication (as mimetic representation, metaphor, metonym, symbol, allegorical allusion, extra-textual or historical reference).5 How a given collage animation is encountered on phenomenological, cognitive and conceptual levels is largely affected by the artist’s compositional strategies as well as the images’ material, representational, historical and connotative properties.6 This chapter aims to illuminate the ways in which Klahr’s particular approach to collage animation in The Pettifogger constructs and conveys narrative meaning. As with many forms of experimental cinema, viewers must learn how to engage with the specific conceptual, formal or narrative logic at work in the animation and decode its image and sound compositions in order to gain access to its narrative. Through its sparse and roughly assembled cut-out images, The Pettifogger presents viewers with an elliptical crime film narrative that must be deciphered on the level of form.

Polyvalence in Lewis Klahr’s collage animations

In ‘Towards a Minor Cinema’, Tom Gunning (1989–90) included Klahr in his list of avant-garde filmmakers working in the 1980s whose films re-engaged with narrative after its reputed rejection by the so-called structural filmmakers of the 1970s. One of the distinguishing features of this ‘minor’ cinema was that its approach to narrative returned to the sort of polyvalent montage that characterised earlier works of the American ‘poetic’ avant-garde.7 These forms of cinema exhibited a ‘highly meaningful flow of images’ – ‘rhythmic montages’, ‘syntagms of images’ and ‘language of juxtaposition’ (Gunning 1989–90, 4) – whose meaning nevertheless evaded straightforward comprehension. Although Klahr often makes use of the iconography and music associated with classic Hollywood genres like film noir and melodrama, his works also share with the poetic traditions of avant-garde cinema an emphasis on atmosphere, lyricism, evocative imagery, metaphoric montage and compositional detail.

The narratives in Klahr’s animations have been variously described by reviewers and critics as ‘archetypal’, ‘compressed’, ‘discontinuous’ and ‘semi-abstract’ (Atkinson 2000; Perry 2010; Klahr 2011). Gunning (1989–90) himself poetically remarked that ‘plots stir just beneath the threshold of perceptibility. The sea swells of these subliminal stories align images into meaningful but often indecipherable configurations’ (4). Indeed, one of the most striking aspects of Klahr’s collage animations is that they provide viewers with a feeling of narrative without clearly communicating precisely what that narrative entails. My analysis of The Pettifogger is intended to go some way towards elucidating how the images’ configurations might be indeterminable yet also meaningful.

Klahr works predominantly with cut-out images from mid-twentieth-century American magazine advertisements, comic books and other printed ephemera, and his signature style has evolved over time. The almost 50 collage films Klahr has made since 1987 offer a subtly diverse array of organisational principles and compositional techniques, ranging from more or less explicitly narrative, to musically and thematically centred, to highly metaphorical and ambiguous. For instance, many of the 12 films in Klahr’s early four-part Super 8 series of collage films, Tales of the Forgotten Future (1988–1991), use advertising imagery to play freely with the generic tropes of Hollywood melodrama, sci-fi, film noir and documentary. Elements of these genres can be seen most clearly in his films In the Month of Crickets (1988), For the Rest of Your Natural Life (1988), The Organ Minder’s Gronkey (1990), Elevator Music (1991) and the Untitled films (1991). With his 16mm series Engram Sepals (Melodramas 1994–2000) and Daylight Moon and Other Constellations (1999–2004), Klahr continued to explore more straightforward narrative, especially in films like Pony Glass (1997), while also venturing into more elusive and associational forms of storytelling, as in Altair (1994), Engram Sepals (2000) and Daylight Moon (2002). His more recent works, the series Prolix Satori (2009–2011) and Sixty Six (2002–2015), are varied in terms of theme, with many of Prolix Satori’s ‘couplets’ combining images with the lyrics of pop songs and the mythopoetic films of Sixty Six forming, in Klahr’s words, more of a ‘cohesive experience’ or ‘associational mindscape’ (Cronk 2016) than an overarching narrative.

The Pettifogger is amongst Klahr’s more overtly narrative works; however, it offers a mixture of poetic abstraction and narrative structure that encapsulates many of the most salient aspects of his filmmaking and storytelling aesthetic. This makes it a productive subject for close analysis, in terms of gaining a clearer understanding of Klahr’s particular approach to collage animation, and as an example of the ways that artists play with modes of expression in experimental animation and cinema more broadly. In the case of The Pettifogger, the diffuse yet potent sensations that Gunning describes are due, in part, to the fact that the narrative appears elliptically in the work. First, The Pettifogger is elliptical in a way that recalls the art cinema of canonical filmmakers such as Federico Fellini and Michelangelo Antonioni, where the causal linking of events is often tenuous and contingent. In The Pettifogger, the main protagonist’s narrative journey appears largely aleatory, and broad swathes of time are often elided and scenes jump from place to place. Borrowing from classical Hollywood cinema, one of the tropes Klahr often uses is the periodic display of changing calendar dates to act as shorthand for the passage of time. However, the work is also an elliptical narrative in the way John P. Powers (2011) describes the term, where ‘the viewer may have difficulty accounting for all of the pieces but nonetheless intuits a strong organizing logic or sense of a narrative trajectory. This allows the filmmaker to retain the semblance of narrative while also subverting it to the associational flow of images’ (101). One of the primary purposes of this chapter is to shed light on how ‘the associational flow of images’ in The Pettifogger interacts with its skeletal ‘semblance of narrative’.

One of the most salient aesthetic features of Klahr’s collage films is what Gunning (1989–90) described as their ‘technical poverty’ and ‘total lack of illusionism’ (5). Making his frame-by-frame animations in his garage studio without an animation stand, Klahr’s films often look as if they have been cobbled together with images cut out of magazines and comic books placed incongruously, and often sparsely, on a variety of flat surfaces. Klahr ‘heightens the stasis already inherent in cut-out animation’ (2011, 396) by using a lower frame rate than traditional animation so that the movements in his films are at times pointedly jerky and jagged, a quality that is mirrored in some of the edges of his cut-outs. It is primarily for this reason that James Peterson (1994) aligned Klahr’s early animations with what he called the ‘bricolage’ approach to collage animation, which led to the misapprehension that his work should not be interpreted ‘centripetally’, as in, where the ‘pull of the “centering” new composition is stronger than the pull of the diverse intertextual references’ (154).

On the contrary, Klahr’s disjointed collage images consistently refer back to an intact diegetic world that the viewer can piece together and imagine as cohesive. As none of the cut-out figures he uses have articulable limbs, their movements are significantly limited; instead of moving realistically, their frozen gestures often float across the surface of the background. Nevertheless, Klahr has a keen sense of dramatic performance and his choices of figures often reflect a desire to capture a distilled representation of the physicality of a moment. This is enhanced by the figures he uses to represent his characters, which are often excised from pre-existing comic book narratives that provide a sense of drama and story in medias res, which he in turn bends to fit the needs of his own story. The expressive physicality of the figures is essential in providing clues as to the psychological and emotional states of the characters at a given time. In addition, their semi-abrupt movements, achieved by frame-by-frame animation, infuse the obviously motionless cut-out figures with a sense of agency. Their postures clearly suggest preceding and succeeding actions, and indeed, it sometimes feels as if examples of Gotthold Lessing’s ‘pregnant moments’ were being shuffled around the frame. This distinctive, ‘impoverished’ style of collage filmmaking is one of the most expressively productive aspects of Klahr’s work.

The semblance of narrative

One of the reasons viewers are able to intuit a sense of organising logic or narrative trajectory in The Pettifogger in particular is that it exhibits some of the characteristics of classical cinematic storytelling. The Pettifogger offers just enough narrative clues to enable us to gain a foothold into the world of the film, and if we further choose to apply a narrative interpretation to the film’s poetically associational aspects, the results can fruitfully flesh out many of the details of that world. The film exhibits signposts, such as recurring characters and places, thematic objects, dialogue and musical cues, which suggest a narrative way of reading the film that draws directly from iconic genres of classical Hollywood cinema such as melodrama and the crime film. Narrative elements – what Gunning (1989–90) elsewhere described as ‘barely graspable narrative events’ (4) – most expressly manifest themselves in the film through the (partially) decipherable actions of its protagonist. These actions tend to take place in scenes that depict perspectivally coherent spaces and locations that are accompanied by more or less appropriate sound effects.

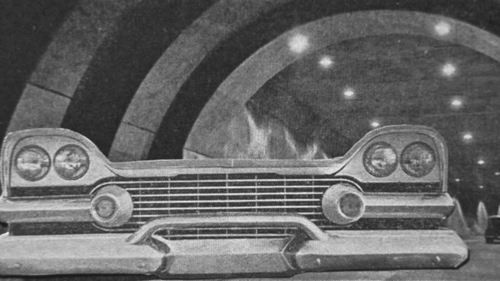

The real difficulty, however, lies in recognising the collaged images as legible signposts. The restricted expression of his animation style on both an aesthetic and formal level sometimes makes it difficult to recognise his use of classic narrative cinematic tropes. Although Klahr’s animations are primarily composed of flat background and foreground images, they nevertheless comprise distinct scenes and sequences whose transitions often mimic conventional editing techniques. A ‘cut’ between scenes is largely determined by a change in background. The backgrounds come to represent locations whereupon images are animated to move either according to a narrative/representational logic or a poetic/associational logic. Sometimes Klahr even mixes metonymy or synecdoche with realism in the same collaged image. An example of Klahr’s use of realism and metonymy (the substitution of something for another thing with which it is associated) can be found in the placement of a cut-out of a folded shirt over a photograph of a bridge, signifying travel. An example of realism and synecdoche (where a part stands in for the whole or vice versa) occurs when a cut-out of a car bumper on a picture of a tunnel or train tracks stands in for a car driving through the tunnel or over train tracks (see Figure 8.1).

FIGURE 8.1 Still: The Pettifogger, Lewis Klahr 2011. An example of realism and synecdoche. Courtesy of Lewis Klahr.

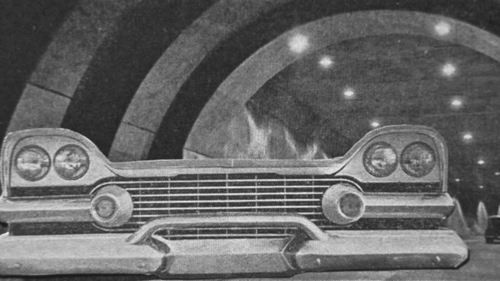

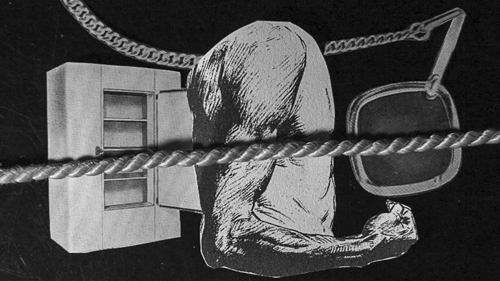

Klahr also regularly and unexpectedly cuts from scenes that exhibit the fixed two-dimensionality of a pictorial plane, with more or less isolated cut-out images or objects placed on top of various types of non-representational backgrounds (see Figure 8.2), to scenes in which depth cues like linear perspective and overlap suggest multi-plane spatial relations between the figures and the background (for instance, where cut-out figures are arranged ‘within’ spatially depictive background images) (see Figure 8.3). Even within the latter kind of collaged shots that cohere spatially in a realistic way, Klahr often combines images from graphically dissimilar origins so that the illusion is never seamless.8

FIGURE 8.2 Still: The Pettifogger, Lewis Klahr 2011. An example of the fixed two-dimensionality of a pictorial plane. Courtesy of Lewis Klahr.

FIGURE 8.3 Still: The Pettifogger, Lewis Klahr 2011. An example of three-dimensional spatial relations between the figures and the background. Courtesy of Lewis Klahr.

The difference in feeling between these two kinds of scenes is phenomenologically palpable; the first kind has a graphic quality that must be interpreted according to the combination of its discrete elements, while the second is much more immediately comprehensible as a unified image. These unified images function at points like establishing shots, allowing viewers to temporarily ‘mentally construct a continuous, unified reality’ (Pratt 2009, 111). In fact, it might be helpful to think of narrative in the film in terms of the distinction made by Russian formalists between syuzhet and fabula, where the syuzhet (or plot) refers to the ways in which the story is presented in terms of its order, emphases and logic and the fabula (or story) is, as David Bordwell (1985) notes, ‘a pattern that perceivers of narratives create through assumptions and inferences’ (49). In the case of Klahr’s work, the syuzhet is presented as a spattering of informative moments, and viewers are left to construct the majority of the fabula for themselves.

Sound plays a vital role in most of Klahr’s collage films. In The Pettifogger, sound effects and location sound often offer clues to narrative events, although most often in an oblique way. The images and sounds most often run parallel to each other, with points of contact where the sounds and music seem intended to correspond directly to the images. This is most potent narratively when the sounds mimetically reinforce characters’ movements so that they achieve what sound film theorist Michel Chion (1994) terms ‘synchresis’ (a combination of ‘synchronism’ and ‘synthesis’), which refers to ‘the forging of an immediate and necessary relationship between something one sees and something one hears’ (5). With Klahr’s work, music shapes the emotional mood of dramatic sequences as in classical Hollywood cinema, building suspense and indicating the tone of climactic moments. The Pettifogger also makes significant use of dialogue heard in voiceover, taken from an episode of the 1960s television programme The Fugitive. The dialogue is loosely attributed to the main characters, providing viewers with clues, for instance, regarding the various types of romantic and business relationships that the protagonist engages in. However, just as often the soundtrack acts as its own evocative sound collage, especially during the more visually abstract sequences, not only creating affective ambience but also inviting viewers to search for meaningful dialectical relationships between images and sounds. Viewers who are familiar with the original narratives imbedded in Klahr’s source material will have access to additional layers of signification, where two narrative threads exist side by side and influence one another in complex ways.

The associational flow

Beyond the ‘semblance of narrative’ within Klahr’s work, however, ‘the associational flow of images’ is an equally important aspect of its structure. Narrative scenes in The Pettifogger are punctuated by episodes of poetic imagery that can be seen to function according to a vertical (poetic) logic of expression rather than a horizontal (prosaic) narrative one. For filmmaker Maya Deren (2002), horizontal development encapsulated conventional film narrative’s logic of actions, primarily based on a linear rationale of cause and effect which propels characters along a trajectory that takes place across a more or less determinable span of time. She conceived of vertical development in a film’s structure as centripetal, where a core emotion or idea is approached via disparate images and scenes that contribute in their own distinctive ways to create a more complex expression of that central feeling or theme.

In The Pettifogger, the poetic resonances that can be drawn from various combinations of imagery might at times be understood to function descriptively, providing details regarding the mood of the film’s world and its characters rather than depicting a straightforward narrative event. During these sequences, all of the compositional elements that make up a shot or sequence of shots may be in meaningful dialogue with any other elements of the work. These semantic and semiotic associative links can in turn simultaneously be based on an array of logics: Narrative, graphic, metaphorical, metonymic or mnemonic. Indeed, these poetic sequences can largely be interpreted according to the principles of polyvalent montage, as defined by Noël Carroll (1996):

In this mode of editing, it is particularly important that each shot is polyvalent in the sense that it can be combined with surrounding shots along potentially many dimensions. That is, this style begins in the realization that a shot may either match or contrast with adjacently preceding or succeeding shots in virtue of color, subject, shape, shade, texture, the screen orientation of objects, the direction of camera or object movement, or even the stasis thereof.

(177)

One of the fundamental heuristic methods that James Peterson (1994) suggests viewers use in order to decipher polyvalent montage in the poetic strain of the avant-garde is to ‘look aggressively to establish coreference [ … ] whenever possible, even by using what might seem to be minor elements in the image’ (42). Indeed, a productive way of approaching these poetic sequences is in making as many connections as possible between images, scenes and sounds. For example, the colour and texture of a particular background might offer an associative link to a particular filmic theme or character’s mood, or the shape and placement of a single object on a non-representational background might have a narrative or metaphorical significance.9 The animated movement of the object within the sequence often stresses this significance. The recurrence of these objects and images, presented in the same and in different combinations throughout a given work, reinforce their importance to its overall intention, even if that intention evades complete elucidation.

Klahr’s use of associational logic in connecting images is part of what makes viewing his films such an intriguing challenge. The other major challenge lies in learning how to decipher the collaged images themselves. It is highly unlikely that viewers could meaningfully connect everything they see in The Pettifogger. It is sometimes difficult to recognise exactly what images and objects are, much less what they are meant to represent. At other times, the images seem to be based on moods or emotional resonances that express feelings that are difficult to articulate, or have a personal significance for Klahr that is inaccessible to viewers. Even the scenes and sequences in The Pettifogger that possess the most clearly narrative elements withhold vital information from viewers as to the exact nature of an action, preferring instead to offer hints and suggestions around central events, often achieved through vague exchanges of dialogue. This does not necessarily detract from the film experience; on the contrary, it is often the untethered, enigmatic elements of the work that evoke the strongest personal response by inviting viewers’ emotions and imaginations to fill in the blanks. There are myriad possible readings of the film with regard to its specific narrative details, and there cannot be any single correct interpretation of it. Nevertheless, in what follows, I attempt to flesh out a reading of the skeletal narrative of The Pettifogger, pulling it up from ‘beneath the threshold of perceptibility’.

Deciphering The Pettifogger

The first clue for entry into The Pettifogger, which is an essential part of how the film enables viewers to begin to construct a fabula through expectation, lies in the title. Coined in the early seventeenth century, the word ‘pettifogger’ has come to refer to ‘a petty practitioner in any activity, a beginner, novice; esp. one who makes false claims to skill or knowledge, a charlatan, pretender’ (Oxford English Dictionary, 1989, s.v. ‘pettifogger’). This title prepares viewers not only to expect the film to focus on a central protagonist, but it also provides them with a clue as to its references to the conventions of the crime film genre. ‘Pettifogger’ also indicates that the nature of the crime that the protagonist is involved in will likely be on a minor scale (which is not to suggest that things could not escalate into more serious affairs). These expectations will not be easily met. However, they can function as a sort of touchstone (or decoder ring) by which the film’s many disparate images may be interpreted.

The Pettifogger takes place over the course of a year in the life of an American gambler and con man. The film’s ‘semblance of narrative’ elliptically follows his daily life as he evades debt collectors, argues with lovers, gambles at casinos and bets on boxing matches, has shady meetings with his older business partner or boss, goes on the road, succumbs to a delirious and amnesiac episode or injury-induced coma (as evidenced by the twenty-minute abstract sequence), ultimately recovers and continues his depressed life of delinquency. The protagonist is represented throughout the film by the comic book version of the actor Robert Vaughn from the popular 1960s television show The Man From U.N.C.L.E. (1964–1968). The continuity this creates between the various incarnations of Vaughn is enough to enable easy identification of the figure as the film’s ‘star’.

In addition to a recurring protagonist, the film offers a number of recognisable settings, some of which are returned to periodically over the course of the film. These are his and his girlfriend’s domestic spaces, which are represented both mimetically and via synecdochic association; for instance, the mundaneness of his bathroom is encapsulated in a black and white image of a soap dish. In another scene a rack of coffee cups, a cuff link and a window sparsely define his kitchen. Lamps and couches indicate living rooms. At other points, travel is suggested when we see pictures of planes taking off either preceded or followed shortly by aerial cityscapes and iconic landmarks (San Francisco and the Golden Gate bridge, Las Vegas and casinos). Being on the road is symbolically represented by a steering wheel placed on top of a cut-out of the United States of America; different states’ licence plates are shown in geographically sequential driving order, and a lone bumper (recognised as the Pettifogger’s car) visits and revisits a photo of a gas station and a postcard of a motel.

The film begins with a twelve-minute prologue during which many of the images that will come to feature prominently in the rest of the film are condensed into an incomplete preview of what is to come. During this preamble a flashing message from a fortune cookie that reads ‘Many possibilities are open to you, take advantage of them’ seems to be directly speaking to its audience as well as indicating the pettifogger’s opportunistic and nomadic lifestyle. The message might be understood as an instruction for how we should encounter the film, encouraging us to make as many connections between the elements as we can. As the clues in The Pettifogger that relate to particular aspects of the film’s world are revealed intermittently and are interspersed with information regarding other aspects of that world, the film makes it frequently necessary for the viewer to connect details retrospectively, building a clearer mental scenario layer upon layer.

Due to the sketchy and partial nature of the depiction of the world in Klahr’s film, we are obliged to recall certain pieces of information in order to orientate ourselves according to the narrative’s temporal and spatial progression (such as keeping in mind which time of year is being represented, or where in the United States the pettifogger is at a given time). For instance, The Pettifogger reveals over the course of the prologue that it begins in the winter of 1963 by showing an image of ‘1963’ imprinted on the granular leathery surface of a mechanic’s guide to automotive parts, and then almost a minute later – after we have been introduced to his relationship with his lady lover and a mysterious transaction with the man in the green jacket – a sequence provides further details in the form of a cut-out circle inscribed with ‘Jan 12’ which circles an isolated milk bottle on another leathery surface. As if to emphasise this information, the next image is of a window with a heater underneath it with snowy trees outside, followed briefly by an image of a snow-covered car headlight. Often, the significance of something will not be revealed for a short period after it is introduced and thus must be retroactively put together.

The significance of sound

The soundtrack in The Pettifogger often corresponds rhythmically to the pacing of the scenes, and it also contributes information about the narrative that is unfolding, sometimes providing direct clues to the action and at other times serving a more atmospheric function (as with the ambient intervals of sounds of a billiards game and a long thunderstorm towards the end). The audio in the prologue is important in that it mimics the condensation of the story being conveyed in the visuals. For instance, the clearly edited sounds of a jazz bar which omits the performances, presenting applause and the indecipherable mumblings of the audience, mimics the formal properties of the film in two ways: It shows the elision of time that is being represented in the film as well as providing clues to an event without disclosing the essential information (in the case of the audio, intelligible words or the musical performance itself).10 Also, the debt collection letters heard on the soundtrack establish that the pettifogger is most likely in financial trouble and under tremendous stress, and this is recalled again and again in the images of empty envelopes and library due date cards. It does not become clear that the voiceover regarding the outstanding debt is a dictation of a letter until the end of the prologue where the man’s patronising, monotonous voice says ‘sincerely yours’.

In other scenes, voiceover dialogue reveals the troubled nature of his romantic relationships. One humorous example of this occurs halfway through the film when, over images of billiard balls and boxers in a boxing ring, an excerpt of Dawn Upshaw singing ‘What A Curse For A Woman Is A Timid Man’ from Gian Carlo Menotti’s radio opera The Old Maid and the Thief (1939) is heard. Upshaw trills, ‘He eats and drinks and sleeps, he talks of baseball and boxing, but that is all!’ This not only provides information regarding the obsessive nature of the gambling protagonist, but it suggests that these are some of the reasons for the pettifogger’s romantic failings.

Some of the clearest narrative events that take place are depicted in conjunction with some form of dialogue, either through voiceover or in speech bubbles. Examples of this can be seen in the scenes in which the pettifogger vaguely receives instructions to ‘get close to’ unidentified people by the names of ‘Palmer’ and ‘Callison’. Later on, a conversation takes place between the pettifogger and a brunette woman in front of a background image of a section of the Las Vegas strip where he invites ‘Mrs. Callison’ to his hotel for a drink (visible in handwritten speech bubbles). She refuses via speech bubble. It remains unclear whether she is the Callison the boss is looking for or the pettifogger is attempting to locate her husband. Later still, we see the first two figures (the boss and the pettifogger) in front of the same strip, where the boss says simply, ‘Don’t let him go!’ before turning around to leave (cleverly shown in a quick succession of three cut-outs of the boss’s face from different angles). Conversations like these convey an air of intrigue along the lines of the crime film genre and suggest that the pettifogger’s actions will relate somehow to carrying out a criminal job.

Shifting perspectives and points of view

Klahr (2011) once explained to an interviewer that ‘The Pettifogger is a diaristic, first person montage full of glimpses, glances and the quotidian’. The film’s tendency towards episodes of associational poetic imagery (especially under the unstable principles of polyvalent montage) means that it may be difficult to recognise that a first person point of view is at times being represented. However, Klahr’s positioning of the figure of the pettifogger at the film’s centre gives viewers the opportunity to interpret the images as representing variously objective and subjective views of the protagonist. In some scenes, we are invited to observe his actions and interactions from the outside and in others we are made privy to his subjective point of view. One example of this takes place early on in the film, where a vacillation between grainy black and white images of a part of a man’s face and a shot of the pettifogger’s face seen above the top of a hand of cards acts as a shot/reverse shot interaction between members of a card game who are scrutinising each other for signs of bluffing.

Recognising the possibility of interpreting these images according to the hermeneutic logic of the pettifogger’s subjective experience unlocks the potential for many of the symbolic and associational aspects of the imagery to be interpreted with much greater narrative clarity. For instance, sequences in which a cigarette suddenly intrudes upon a scene (such as a baseball or poker game) may be interpreted as being seen from the point of view of the pettifogger while smoking. Poker chips hover over a picture of the bathroom; playing cards and drink stirrers appear everywhere, showing his obsession with gambling, which in turn is perhaps spurred by the constant reminder of his financial debt (connected tangentially to the voiceover debt letter by empty envelopes). This is not to say, of course, that these are the only ways of interpreting the imagery, and indeed, the same images can represent different aspects of the fabula over the course of the film. For instance, playing cards are a motif in the film that indicate his gambling habits, but it might equally be said that at points we are encouraged to identify the pettifogger hierarchically as the jack and the other man, his boss, as the king. The recurrence of scenes featuring play money may indicate straightforward financial transactions taking place, while also suggesting that the money may be counterfeit. Depending on the pettifogger’s degree of villainy, the changing licence plates may also be interpreted as an indication that he is a serial car thief, stealing a new car in each new state, or else simply changing licence plates to evade detection.

The long stretch towards the end of the film where the image sequences grow increasingly abstract, interspersed with increasing intervals of blackness and accompanied by one long continuous recording of a thunderstorm, is a departure from the tone of the rest of the work, indicating a potential shift in perspective or consciousness. Single images (of cards, doors, bridges, suitcases, patterned paper, cigarettes, booze, tyres, casino chips, fabrics, naked women) flicker rapidly onscreen as if the elements that made up the film (and the pettifogger’s life) up until this point are being digested in the depths of an unconscious mind. This interpretation is strengthened when, in the midst of this contemplative sequence, voices are again heard on the soundtrack and an image of a ceiling light viewed from below indicates a point of view shot of the pettifogger, just awoken. A voice, which seems to be that of a police officer, questions a man about how he came to be injured. Another man’s voice recounts being struck when getting out of the car to get cigarettes. He states his name as Mr Browning (surely not his real name), and indeed the officers find no ID in his possessions. He has a mere 12 dollars in his pockets. Then the thunderstorm and the semi-erratic images return until the storm ends abruptly and an image of the pettifogger in motion is juxtaposed with the sounds of footsteps running on dried leaves (suggesting autumn) and alarm bells going off in the distance.

A subsequent image of a policeman suggests that the pettifogger has committed a theft or similar crime. Multiple images of fingerprints suggest that his crime is being investigated – perhaps that he is being pursued, and a phone conversation with a woman who says she’s moving out indicates that the pettifogger hasn’t woken to a more fortunate life. Airline tickets, aerial photographs of parking lots, flying geese and motel rooms suggest that he is travelling again. In the final sequences, the rainstorm returns and we see a picture of a Christmas ornament in a tree, perhaps suggesting that a full year has passed. The credits are followed by the sounds of a car driving and two final enigmatic images, ending silently on another glimpse of the image of the ceiling light seen from below. Linking back to the images of motel rooms and travel, I imagine the pettifogger waking up, yet again, alone in a strange room, doomed to repeat the same series of petty criminal actions until he finally ends up in jail (the threat of which has loomed throughout the work in the form of a floating square patch of wire mesh).

Conclusion

The potential for Klahr’s experimental, and at times abstract, work to resonate differently for each viewer is part of the compelling power of The Pettifogger. The descriptions of obscured narrativity and meaningful indecipherability bear witness to the rich and nebulous experience of viewing his work for the first time – and arguably subsequent times as well. These qualities are integral to them, and it is doubtful, not to mention undesirable, that they would be completely clarified even after a hundred viewings. However, one of the benefits of studying a work as densely layered and cryptically composed as The Pettifogger is that the potential to recognise patterns, meaningful connections and expressive tropes has the opportunity to develop more fully from repeated viewings and close analysis. Klahr’s sparse, semi-mimetic audio-visual configurations and his combined use of poetic and prosaic expressive logic require viewers to actively integrate the elements of his collage in order to arrive at a coherent narrative interpretation. By responding to aural cues, following the narrative signposts (however indeterminate) and interpreting the polyvalent graphical compositions of The Pettifogger, we gradually are able to bring our own versions of its ‘submerged’ narrative to the surface.

The amount of time and energy that goes into the making of experimental animation is often directly inverse to the amount of screen time they take up, as well as to the amount of critical attention they receive. It is my hope that the close reading provided in this chapter encourages others to engage in the formidable task of analysing experimental animations that are often staggeringly dense and difficult to describe. The benefits, I argue, are well worth the effort.

Notes

1 Up until quite recently, experimental animation has largely been addressed either as a subcategory or technique of avant-garde cinema (and, to a lesser degree, artists’ film and video) or in isolated treatments within animation studies.

2 For instance, Russett and Starr’s seminal text Experimental Animation: Origins of an Art identifies ‘pictorial’ and ‘imagist’ animators who produced narrative-based works, such as Lotte Reiniger, Berthold Bartosch, Alexander Alexeieff and Claire Parker, Harry Smith and Larry Jordan.

3 He is represented by Anthony Reynolds Gallery in London.

4 Part of this association, however enigmatic and oblique, can be traced back to P. Adams Sitney’s quasi-narrative interpretations of American collage animators like Harry Smith and Lawrence Jordan in his highly influential Visionary Film (2002).

5 Suzanne Buchan (2010) refers to this feature as ‘portmanteau images’, where fragments of different images function ‘like the lexeme fragments of different words’ (187).

6 Other experimental animators working with collage include Stan VanDerBeek, Robert Breer, Carmen D’Avino, Martha Colburn, Janie Geiser, Jodie Mack, Kelly Sears, Jeff Scher, Frank Mouris, Paul Vester, Dalibor Barić, Kate Jessop, Amy Lockhart, Nathanial Whitcomb, Natalie Wilkin, Fritz Steingrobe and Hanna Nordholt, Virgil Widrich and Osbert Parker.

7 This refers to James Peterson’s (1994) grouping of P. Adams Sitney’s categories of American visionary film (namely, the ‘trance film’, the ‘lyrical film’ and the ‘mythopoetic film’). Examples include Maya Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), Stan Brakhage’s Window Water Baby Moving (1959) and Doug Haynes’ Common Loss (1979).

8 Such a scene appears in Elevator Music (1991) where a photographic cut-out of an actress is shown fellating an illustrated male figure.

9 For instance, Klahr uses the colour green as a motif in Daylight Moon (which represents a character’s subjective experience) or blue in Altair (which is a much more associational, metaphorical film).

10 Klahr is often obliged to edit his materials in order to avoid copyright infringement, which in turn provides opportunities to problem-solve and create creative storytelling techniques.

References

Atkinson, Michael. ‘Culture Consumer Lewis Klahr: The Re-Animator.’ The Village Voice. May 16 2000, accessed May 10 2018. www.villagevoice.com/2000–05–16/film/culture-consumer-lewis-klahr/.

Bordwell, David. Narration in the Fiction Film. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985.

Bordwell, David and Kristin Thompson . Film Art: An Introduction. 10th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2012.

Brakhage, Stan. Window Water Baby Moving US, 1959. Film.

Buchan, Suzanne. ‘“A Curious Chapter in the Manual of Animation”: Stan VanDerBeek’s Animated Spatial Politics.’ Animation: An Interdisciplinary Journal 5, no. 2 (2010): 173–196.

Carroll, Noël. ‘Causation, the Ampliation of Movement and Avant-Garde Film.’ Theorizing the Moving Image. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Chion, Michel. Audio-Vision. Translated by Claudia Gorbman . New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

Cronk, Jordan. ‘Era Extraña: Lewis Klahr on Sixty Six.’ Cinema Scope Magazine, Issue 66, 2016, accessed May 2018. http://cinema-scope.com/cinema-scope-magazine/era-extrana-lewis-klahr-sixty-six/.

Deren, Maya. Meshes of the Afternoon. US, 1943. Film.

Geiser, Janie. Ghost Algebra. US, 2009. Film.

Gunning, Tom. ‘Towards a Minor Cinema: Fonoroff, Herwitz, Awesh, Lapore, Klahr and Solomon.’ Motion Picture 3, nos. 1–2 (1989–90): 2–5.

Haynes, Doug. Common Loss. US, 1979. Film.

Huggins, Roy. The Fugitive. US, 1963–1967. Television series.

Jordan, Larry. Sophie’s Place. US, 1986. Film.

Klahr, Lewis. ‘A Clarification.’ The Sharpest Point: Animation at the End of Cinema. Edited by Chris Gehman and Steve Reinke . Toronto: XYZ Books, 2005, 234–235.

Klahr, Lewis. ‘Flotsam and Jetsam: The Spray of History.’ Animation: An Interdisciplinary Journal6, No. 3 (2011): 387–398.

Klahr, Lewis. In the Month of Crickets. US, 1988. Film.

_____. For the Rest of Your Natural Life. US, 1988. Film.

_____. Tales of the Forgotten Future. US, 1988–1991. Film.

_____. The Organ Minder’s Gronkey. US, 1990. Film.

_____. Elevator Music. US, 1991. Film.

_____. Untitled. US, 1991. Film.

_____. Altair. US, 1994. Film.

_____. Daylight Moon and Other Constellations. US, 1999–2004. Film.

_____. Pony Glass. US, 1997. Film.

_____. Engram Sepals. US, 2000. Film.

_____. Daylight Moon. US, 2002. Film.

_____. Prolix Satori. US, 2009–2011. Film.

_____. The Pettifogger. US, 2011. Film.

_____. Sixty Six. US, 2002–2015. Film.

Lessing, Gotthold Ephrain. Laocoön: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry. Edited and translated by Edward Allen McCormick . Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984.

Lowne, James. Our Relationships Will Become Radiant. UK, 2011. Film.

MacDonald, Scott. ‘“Poetry and the Film: A Symposium” (with Maya Deren, Willard Maas, Arthur Miller, Dylan Thomas, Parker Tyler), 10/28/53.’ Cinema 16: Documents Toward a History of the Film Society. Edited by Scott MacDonald. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2002, 202–212.

McGillicuddy, Louisa. ‘Lewis Klahr’s The Pettifogger: Collaging the crime – in pictures.’ The Guardian. November 1 2011, accessed May 2018. www.guardian.co.uk/film/gallery/2011/nov/01/lewis-klahr-the-pettifogger-in-pictures.

Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. 20 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989. Continually updated at www.oed.com/.

Perry, Colin. ‘Lewis Klahr.’ /P Engine: Moving Image Transmission. October 2010, accessed May 2018. http://web.archive.org/web/20160113122539/http://www.apengine.org/2010/10/lewis_klahr_by_colin_perry/.

Peterson, James. Dreams of Chaos, Visions of Order: Understanding the American Avant-Garde. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1994.

Peterson, James. ‘Is a Cognitive Approach to the Avant-garde Cinema Perverse?’ Post-Theory. Edited by David Bordwell and Noël Carroll . University of Wisconsin Press, 1996, 108–129.

Pitt, Suzan. Asparagus. US, 1979. Film.

Powers, John P. ‘Darkness of the Edge of Town: Film Meets Digital in PhilSolomon’s In Memoriam (Mark LaPore).’ October 137, Summer (2011): 84–106.

Pratt, Henry John. ‘Narrative in Comics.’ The Poetics, Aesthetics, and Philosophy of Narrative. Edited by Noël Carroll . Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd., 2009, 107–117.

Russett, Robert and Cecile Starr . Experimental Animation: Origins of a New Art. New York: Da Capo, 1988.

Sitney, P. Adams. Visionary Film: The American Avant-Garde 1943–2000. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Smith, Harry. Heaven and Earth Magic. US, 1957–62. Film.

Taberham, Paul. Lessons in Perception: The Avant-Garde Filmmaker as Practical Psychologist. Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2018.

Wrake, Run. Jukebox. UK, 1994. Film.