Lassen Peak from Upper Meadow

Exploring Lassen Volcanic National Park

Like gigantic geysers spouting molten rock instead of water, volcanoes work and rest, and we have no sure means of knowing whether they are dead when still, or only sleeping.

—JOHN MUIR, The Mountains of California

Lassen Peak from Upper Meadow

In everyday life, taking off your socks is an unnoticed chore; peeling them off after a long day’s walk is sheer delight.

—COLIN FLETCHER, The Complete Walker IV

ALONG THE PACIFIC RIM’S RING OF FIRE, the Cascade Mountains reach as far north as Mount Garibaldi in British Columbia. This range of massive volcanoes stretches south through Washington, Oregon, and Northern California. At its southern tip lies Lassen Peak, resting from its most recent eruption in 1917. Surrounding the mountain is Lassen Volcanic National Park, a wild and exotic Northern California treasure.

You can choose from two walkabouts through this enchanted land. The first, a two-day, 22.2-mile hike, requires two cars. It explores the park from its northeast to southwest corners. Starting in a land of lava beds and painted cinder dunes, you hike south to a lush hot-springs valley. The trail on the second hiking day explores mountain lakes and streams, deep glaciated canyons, and otherworldly hydrothermal landscapes.

The second walkabout is a 19.4-mile loop that starts high at Summit Lake and requires only one car. It explores the central park—a mountainous land of forests, lakes, and streams. Each trek offers a spectacular waterfall, mountain lakes for swimming, and windows into the earth’s fiery interior.

The mountains of Lassen Volcanic National Park

Both walkabouts stop over at Drakesbad Guest Ranch, one of only two lodgings in the park. Stay a few days and enjoy soaking in the hot springs. Explore the verdant Warner Valley and surrounding landscape of boiling lakes and steaming fumaroles. Relax with fine dining and perhaps a therapeutic massage.

ITINERARIES

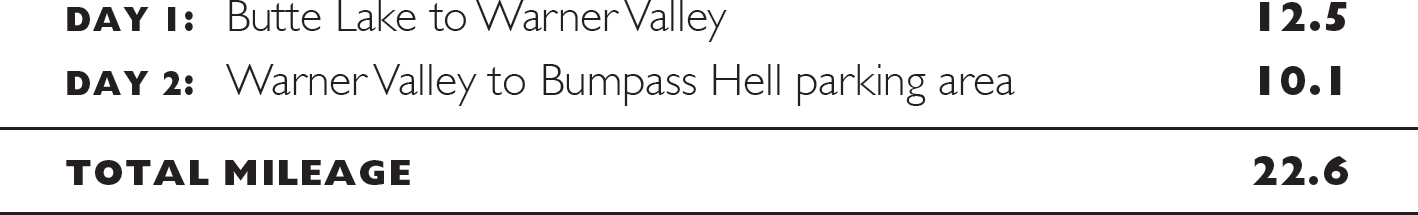

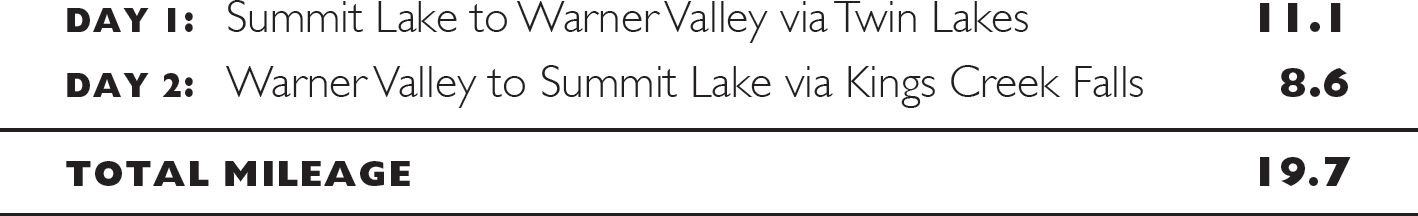

Butte Lake to Bumpass Hell

Summit Lake Loop via Warner Valley

BUTTE LAKE TO BUMPASS HELL

Day 1: Butte Lake to Warner Valley

THE ONE ROAD THAT TRAVERSES THE PARK, CA 89, winds through its western half. My friend Scott drove up from Reno, and I came from the Bay Area. We met at the visitor center in the southwest corner of the park. A walkabout is a great way to reunite with distant friends and to spend long days together enjoying nature’s beauty at 2 miles an hour.

Dropping a car at the Bumpass Hell parking lot, we drove north out of the park and then east on CA 44, reentering on Butte Lake Road in the park’s northeast corner (see Transportation, for driving directions). Butte Lake has a campground and ranger station. At 6,053 feet, the lake’s western shoreline was formed by ancient lava flows that partially filled its basin. Frozen rivers of black, ragged lava reach 100 feet high, shaping the convoluted shore of the lake. As we started our hike, a great blue heron stalked and a pod of mule deer grazed in the grassy shallows at the water’s edge.

The trail heads south 1.2 miles through soft volcanic sand, cinders, until it reaches Cinder Cone. Eruptions in the 1600s formed the 750-foot-high cone and the Fantastic Lava Beds that flowed toward Butte Lake. The cone has an angle of repose of 30–35 degrees, the maximum angle that still prevents cinders from rolling down its side. It was formed by basaltic lava, which is rich in magnesium and iron. Lighter cinders were blasted for miles, and heavy volcanic bombs litter the base of the cone. A few stunted pines grow on its flanks, but the dense cinders discourage much vegetation. The ponderosa and Jeffrey pine forest surrounding the cone is thin, and other vegetation is sparse in the sandy soil.

It is difficult to distinguish Jeffrey pines from ponderosa pines. Both are mighty giants that can reach 200 feet in height. Each bears 8- to 10-inch needles in bundles of three. Their thick bark is an intricate and irregular patchwork. The Jeffrey flourishes at elevations between 6,000 and 9,000 feet in the Sierra, while ponderosas grow between 2,000 and 7,000 feet. In this zone they overlap. As we hiked around Cinder Cone, Scott approached one of the giants, put his nose into a deep furrow in the patchwork bark, and, smelling a light fragrance of vanilla, declared this one to be a Jeffrey. The scales on the cones of a ponderosa face outward and prickle when handled, but these cones had a smooth surface, confirming its identity.

If you are ambitious, you can climb the steep trail to the top of Cinder Cone over loose cinders. Two concentric paths circle the lip of the cone and the inside of the crater. The view from the top is worth the climb—the painted dunes, fantastic lava beds, Butte and Snag lakes, and, to the west, the 10,457-foot snowcapped Lassen Peak.

The great mountain and surrounding parkland lie at the southern end of the Cascade Range, but the mountain borders the Northern Sierra. John Muir referred to it as part of the Sierra when he visited Cinder Cone and wrote in The Mountains of California:

The Cinder Cone near marks the most recent volcanic eruption in the Sierra. It is a symmetrical truncated cone about 700 ft. high, covered with grey cinders and ashes, and has a regular unchanged crater on its summit, in which a few small two-leaved pines are growing. . . . Before the cone was built a flood of rough vesicular lava was poured into the lake, cutting it in two, and overflowing its banks, the fiery flood advanced into the pine-woods, overwhelming the trees in its way, the charred ends of some of which may still be seen projecting from beneath the snout of the lava-stream where it came to rest. Later still there was an eruption of ashes and loose obsidian cinders, probably from the same vent, which, besides forming the Cinder Cone, scattered a heavy shower over the surrounding woods for miles to a depth of from six inches to several feet.

The history of this last Sierra eruption is also preserved in the traditions of the Pitt River Indians. They tell of a fearful time of darkness, when the sky was black with ashes and smoke that threatened every living thing with death, and recount that when at length the sun appeared once more, it was red like blood.

Muir died in December of 1914 at age 76, only six months after the next great eruption in the Cascades, Lassen Peak.

This section of the hike follows Nobles Emigrant Trail, forged by William Nobles in 1852 during the peak of the gold rush. Thousands of treasure seekers passed this way in the 1850s. It proved superior to the dangerous Lassen Trail that had opened in 1848 as a route from the Humboldt River in Nevada to the upper Sacramento Valley. The trail was used as a wagon route to California until 1869, when the Transcontinental Railroad was completed and the pioneer wagon roads fell into disuse.

Continue on the trail south of Cinder Cone toward Lower Twin Lake. After another 0.5 mile Nobles Emigrant Trail veers west. Stay left at this junction. Leaving the soft cinders behind, the trail becomes firm and easy. You pass three lovely jewel lakes—Rainbow, Lower Twin, and Swan. Wildflowers line the paths near the lakes until mid-July. When we hiked, late in the season, the second week of September, these small lakes were the perfect temperature for a leisurely swim.

Cinder Cone

The eastern half of the park has low mountains, meandering creeks, and dozens of lakes. This trail is an easy stroll for most of the first day’s hike, rolling gradually between 6,300 and 6,800 feet through forests of white firs and Jeffrey, lodgepole, and western white pines. Lassen is one of the most lightly used national parks, averaging fewer than 500,000 visitors a year. Very few stray far from the Lassen Park Road (CA 89) in the park’s western half. Only backpackers and a few day-trippers venture into the east side. We met only one other hiker until we reached Warner Valley.

Join the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) at Lower Twin Lake, and head south, passing through several sections where fires have scarred the forest. Marked with bear scat and deer tracks, the trail turns southwest and descends through Grassy Swale along a meandering brook. The forest becomes lush, and boardwalks span marshy sections of the trail. Cross the brook and then Kings Creek at the Corral Meadow junction. Follow the signs south toward Warner Valley. The trail climbs 500 feet through a series of switchbacks until it reaches the crest overlooking Warner Valley and Drakesbad Guest Ranch. Descend the steep trail into Warner Valley Campground, turn right, and walk up the road a short distance to Drakesbad.

Warner Valley and Drakesbad Guest Ranch

Drakesbad Guest Ranch is a rustic hideaway at the south central end of the park. Hunters, trappers, and sheepherders visited the Warner Valley following the gold rush, but it was first settled by German immigrant E. R. Drake in the 1860s. Occasional visitors found him and camped for a few nights, enjoying soaks in his hot springs, but Drake valued his privacy more than profit and did little to develop a tourist business.

That changed in 1900, when Alex and Ida Sifford paid a visit and thought they had found paradise. They purchased the land from Drake for $6,000 and opened a rustic guest ranch, which the Sifford family operated until 1958, when they deeded it to the National Park Service. One of only two lodgings in the park, it is a gem that merits a stay of at least a few nights.

We arrived in time for the weekly barbecue feast. Guests gathered at picnic tables outside the lodge while Ed Fiebiger, who with his wife, Billie, hosted Drakesbad for 21 years, grilled steaks, chicken, and portobello mushrooms. There were buckets of beans, potato salad, and beer. As I savored a barbecued steak, I laughed at the thought that in spite of days of hiking, this adventure was one more walkabout where my caloric intake was going to exceed calories burned.

After all the guests were served, Ed joined us at our table. A jovial man with a thick shock of blond hair sprouting from his visor, he has a deep affection for Drakesbad. Pointing at Scott’s bald head, he said, “Do you like my hair?” We agreed it looked good. He whipped off his visor, and the hair came off with it, exposing his shining scalp. Scott’s face lit up, and he wrote down the website where he could purchase this marvelous invention. They even have visors with ponytails, according to Ed. Scott’s eyes showed that his imagination was stirring with the possibilities. Ed and Billie have “retired” from hosting Drakesbad, though Billie still manages reservations and Ed relieves the current host, Nick, on his days off.

Barbecue night at Drakesbad Guest Ranch

Hot Springs Creek meanders along the south side of the broad valley. Wildflowers grace the meadows and line the streams in the early season. Eagles and ospreys call Warner Valley home for part of the year. Mule deer gather in the meadows to graze at dusk. In the early morning, while enjoying a cup of coffee on our porch, we watched them retreat delicately and unafraid back into the woods. Deep in the night, listen for the nervous whinnying of Drakesbad’s horses, signaling a nocturnal visit from the valley’s black bears.

A generator provides electricity to the lodge, but kerosene lamps light the cabins. The absence of internet or cell phone coverage helps you unwind and tune into the beauty of Warner Valley. A hot spring heats the pool to between 95°F and 105°F. Even summer nights at this elevation (5,700') are cool, perfect for floating in the warm waters and gazing at the star-filled sky. Enjoy three hearty meals a day with plenty of fresh fruits and vegetables, along with a wide selection of wines and beer. Take short day hikes to the thermal hot spots in the south end of the park—Devils Kitchen, Boiling Springs Lake, and Thermal Geyser—or swim in lovely Dream Lake. Enjoy horseback riding or fly-fishing. The weary peregrinator might also want to be pampered with a therapeutic massage.

Before Euro-Americans first explored Warner Valley, it was part of the territory claimed by the Mountain Maidu, one of four tribes—including the Yahi, Yana, and Atsugewi—who spent summers in the park. They enjoyed a diverse diet of fish, game, seeds, nuts, and roots. Like rice in many Asian cultures, the acorn was the central and pervasive food for the Indians of Lassen. Living in small tribes, the village or group of small villages acted as a self-governing unit. Warfare was unusual, brief, and measured. Cool-headed chiefs would quickly negotiate the end of hostilities, and peace would return.

The Yana and Yahi’s territory spread from Lassen Peak west to just above California’s Central Valley. It is a rugged, mountainous land with dense forests and steep river canyons. The tribes probably lived in California for 3,000–4,000 years and settled in their Lassen-area home more than 1,000 years ago. Their population never exceeded 2,000–3,000. To get a sense of their territory, drive CA 32 between the park and Chico along Deer Creek. It is still almost impenetrable, a land of steep woods cut by raging rivers. The population of the Yana and Yahi territory may be no more dense today than it was in 1850.

They lived in small villages, each family with a conical lodge 10 feet high and 20 feet around. The exterior of each lodge was overlaid with slabs of pine or cedar bark, and the interior floors and walls were lined with mats made of tule reeds. At the center was a fire pit for cooking and warmth. They were cozy dwellings in a land where the climate can be harsh. In the hottest months of summer, the Yana and Yahi moved up the slopes of Lassen Peak. They called the mountain Wagaupa, or Little Shasta.

Unlike California’s coastal Indians, who were decimated by the missions, the Indians of Lassen were relatively untouched by Spanish and Mexican rule. But after 1848, when gold was discovered and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ceded California from Mexico to the United States, gold seekers flooded the state, and the Yana and Yahi people were plagued by Euro-American diseases for which they had no immunity—smallpox, tuberculosis, malaria, and dysentery. The concept of private property disrupted their way of life and livelihood, leading to conflicts with settlers. Wanting to protect their property and lives, the newcomers sent raiding parties to exterminate the Indians. They succeeded, and by 1865 the Yana were eliminated.

Between 1865 and 1867 armed raiding parties attacked Yahi villages along Mill Creek and murdered all but a handful, who then went into hiding. Rumors of a small band of Yahi living in the rugged forests along Deer Creek persisted for years. In 1908 a surveying party came across a hidden Yahi camp. The occupants melted back into the forest, and the surveyors took all their tools, blankets, and other implements as souvenirs. The next day, feeling remorseful, they returned to the camp to try to make some restitution, but the Indians had fled, now trying to live in a shrinking land without their means of subsistence.

In 1911 the last surviving Yahi, named Ishi, came out of the mountains to a slaughterhouse near Oroville. He was naked and starving. The sheriff, not knowing what to do with this man from another world, locked him in jail. To the sheriff’s relief, Professor T. T. Waterman, an anthropologist from the University of California, visited Ishi and made a connection using words of the Yahi’s closest relatives, the Nozi Indians. Waterman brought Ishi back to the university’s museum, where he lived until his death from tuberculosis in 1916. The final member of the Yahi tribe had perished. Theodora Kroeber’s wonderful book, Ishi in Two Worlds, recounts the life of the Yahi and of Ishi, a man of great dignity, curiosity, and wisdom.

Day 2: Warner Valley to Bumpass Hell

LEAVING DRAKESBAD GUEST RANCH, return to the Warner Valley Campground and the PCT. The trail climbs out of the valley, and in another mile, you reach a junction where you take the left fork leaving the PCT. The trail ascends gradually along the northern rim of Hot Springs Creek Canyon. Pass Bench Lake at 3.1 miles, a shallow basin that forms a 4-foot-deep pond in the spring. When we hiked by in September, the lake was completely dry, a dusty bowl adorned with balanced rock art, awaiting the winter snows.

After a short climb, the trail drops into the Kings Creek watershed. The forest becomes dense as you descend, and the roar of Kings Creek Falls (6,900') climbs to greet you. Cross the creek on a log bridge, and turn downstream a short distance to the overlook of the spectacular falls where Kings Creek drops 50 feet, crashing over a natural rocky staircase.

The trail follows the creek upstream 1.2 miles to Kings Creek meadows and the park road. When it forks with an equestrian trail to the right, take the left fork, which climbs a narrow gorge where the creek plunges, cascading over narrow stairsteps. At the top of the cascades, you stroll through an enchanting alpine plateau forested with red fir and lodgepole pines.

Cross the park road and enter Upper Meadow. Kings Creek meanders quietly through the grassy meadow, and to the northwest, massive Lassen Peak towers above.

Few people had visited what is now Lassen Volcanic National Park before May 30, 1914, when, after a 27,000-year slumber, the quiet volcano suddenly erupted, sending a cloud of smoke and steam high into the sky. Tourists, scientists, and reporters came to watch occasional volcanic bursts and to climb the mountain to the newly formed crater.

Ten more eruptions led up to the great blasts of May 1915. The mountain blew on May 19, and great rivers of lava poured down its west and northeast flanks, melting snow and creating a pyroclastic flow—a raging mile-wide flood of ash, water, and mud—that crashed into Lost and Hat Creeks. The muddy torrent picked up 20-ton boulders and swept them down the mountain.

The most powerful eruption occurred on May 22, sending a mushroom cloud soaring 30,000 feet into the sky and spewing ash as far as Winnemucca, Nevada, 200 miles away. A horizontal blast blew off the face of the mountain and sent a shock wave that uprooted forests and snapped trees as if they were matchsticks.

Benjamin F. Loomis photographed the eruption and its aftermath. His photos can be viewed in the Loomis Museum at Manzanita Lake. He described the May 22 blast:

The eruption came on gradually at first getting larger and larger until finally it broke out in a roar like thunder; the smoke cloud was hurled with tremendous velocity many miles high, and rocks thrown from the crater were seen to fly way below the timber line before they struck the ground.

Bumpass Hell—fumaroles, boiling springs, and bubbling mud pots

Eruptions then tapered off until they stopped in 1917. The next eruption in the Cascades, that of Mount St. Helens, wouldn’t happen until more than 60 years later. Lassen’s fiery blasts sparked the public’s imagination, and in 1916 President Woodrow Wilson signed legislation declaring Lassen a national park.

There is no formal trail through Upper Meadow, but hike up the north side of the road until you see the entrance to the Kings Creek picnic area. Cross the road and hike through the picnic area to the trailhead to Bumpass Hell. The trail from Kings Creek picnic area to the Bumpass Hell parking lot provides some of the most spectacular vistas in the park. You pass through forests of lodgepole pine, mountain hemlock, and ponderosa pine. Fields of lupine and other wildflowers abound through mid-July. The trail swings by Cold Boiling Lake, a pretty mountain pond in a grassy knoll, where cold gasses bubble up through the earth. As it climbs, beautiful views open to the south. Crumbaugh Lake lies below, deep in a valley surrounded by lush meadows. In the distance stand Saddle Mountain, Mount Harkness, the north rim of Warner Valley, Lake Amador, and a succession of ridges stretching to the horizon.

After hiking 2.8 miles from the Kings Creek picnic area, you arrive at Bumpass Hell, a thermal wonderland of fumaroles, boiling springs, and bubbling mud pots. A boardwalk takes visitors through this eerie landscape, the largest hot spot in the park. The same magma that caused the eruptions of Lassen Peak in 1915 still superheats water reservoirs 3 miles deep in the earth. Steam works its way to the surface at Bumpass Hell as well as at Devils Kitchen, Boiling Springs Lake, and Thermal Geyser a dozen miles southeast. John Muir wrote in The Mountains of California:

Lassen’s Butte is the highest, being nearly 11,000 ft. above sea-level. Miles of its flanks are reeking and bubbling with hot springs, many of them so boisterous and sulphurous they seem ever ready to become spouting geysers like those of the Yellowstone.

Kendal Van Hook Bumpass, a cowboy, explored this area in 1864 and filed a claim for the mineral rights, also hoping to turn it into a tourist attraction. While venturing too close to a mud pot, his foot broke through the thin crust, and his leg plunged into boiling mud. He managed to recover, and a newspaper reporter talked him into returning to the site of the accident. Lightning struck twice—Bumpass made another false step, crashing through the eroded crust into 240°F boiling mud. This time the leg could not be saved and had to be amputated. Despite rumors to the contrary, there is no historical record that our hero was henceforth known as Stumpy Bumpass.

The final leg of the trail climbs to 8,400 feet, the highest point on this walkabout. While dropping down to the parking lot, you pass Lake Helen, with magnificent Lassen Peak in the background. Stop here for a moment before climbing into your car; breathe the crisp mountain air, and savor your exploration of one of America’s most spectacular and least-visited national parks.

SUMMIT LAKE LOOP VIA WARNER VALLEY

Day 1: Summit Lake to Warner Valley

THE SECOND WALKABOUT is a 19.7-mile loop with two hiking days and requires only one car (see Transportation, for driving and parking directions). This walkabout starts and ends at lovely Summit Lake, perched at 7,000 feet in the shadow of massive Lassen Peak. The hike wanders through the park’s central region past crystalline lakes and along mountain streams, with a stopover at Drakesbad Guest Ranch, where you can enjoy a soak in the hot springs and civilized comforts in a rustic setting.

Leave your car in the overnight parking area near the Summit Lake ranger station, and follow the trail to the northeast corner of the lake. Hiking along the eastern side of the lake, you reach a junction. Take the left trail toward Echo Lake. You’ll return on the trail to the right.

On a calm day, stop to enjoy the view of 10,457-foot, snowcapped Lassen Peak reflected in the sparkling waters of Summit Lake. The massive volcano is resting since its last eruption a century ago. (See Lassen Peak.)

The trail climbs for a mile until the turnoff to Bear Lakes. Don’t forget to look behind you—inspiring views of the mountain open up on this stretch. A short distance beyond this junction, the trail descends to Echo Lake. Wildflowers flourish along its shoreline in the early season.

After climbing out of the Echo Lake basin, the trail continues to descend past tiny ponds to Upper Twin Lake. Follow the trail along the north shore of Upper Twin Lake. The trail divides as you approach Lower Twin Lake. Take the right fork along the south shore of Lower Twin Lake to the PCT.

Heading south on the PCT, you pass through several sections where fires have scarred the forest. The trail is marked with bear scat and deer tracks. Lassen is one of the most lightly used national parks, averaging fewer than 500,000 visitors a year. Very few stray far from Lassen Park Road (CA 89). Only backpackers and a few day-trippers hike this far east. You may have this section of the trail all to yourself.

The PCT turns southwest and descends through Grassy Swale along a meandering brook. The forest becomes lush, and boardwalks span marshy sections of the trail. Cross the brook and then Kings Creek at the Corral Meadow junction. Follow the signs south toward Warner Valley. The trail climbs 500 feet through a series of switchbacks until it reaches the crest overlooking Warner Valley and Drakesbad Guest Ranch. Descend the steep trail into Warner Valley Campground, turn right, and walk up the road a short distance to Drakesbad (see page 96 for a description of Drakesbad and the area’s history).

Summit Lake and Lassen Peak

Day 2: Warner Valley to Summit Lake

LEAVING DRAKESBAD GUEST RANCH, return to the Warner Valley Campground and the PCT. The trail climbs out of the valley, and in another mile you reach a junction where you take the left fork leaving the PCT. The trail ascends gradually along the northern rim of Hot Springs Creek Canyon. You pass Bench Lake at 2.8 miles, a shallow basin that forms a 4-foot-deep lake in the spring. When we hiked by in September, the lake was completely dry, a dusty bowl adorned with balanced rock art, awaiting the winter snows.

After a short climb, the trail drops into the Kings Creek watershed. The forest becomes dense as you descend, and the roar of Kings Creek Falls (6,900') climbs to greet you. Cross the creek on a log bridge, and turn downstream a short distance to the overlook of the spectacular falls where Kings Creek drops 50 feet, crashing over a rocky natural staircase.

At Kings Creek Falls, follow the signs toward Corral Meadow. The Kings Creek Trail follows the creek drainage on its north side, gradually descending over the course of 2 miles to the junction of the trail to Summit Lake near the confluence of Kings and Summit Creeks. The trail to Summit Lake ascends through verdant meadows and crosses several spring-fed streams that flow into Kings Creek. You emerge into Summit Lake’s south campground. Walk to the lake and follow the trail around the east shore past the north campground to your car.

You may want to stop for one final rest on the eastern shore of Summit Lake to take in the awesome grandeur of Lassen Peak and its reflection in the crystal-clear waters. The giant rests while, deep in the earth’s bowels, molten lava boils, straining to rise to the surface, erupt, and reshape the mountain once again. What better way to explore this ever-changing and enchanting land than a walkabout with a good friend?

THE ROUTES

All mileages listed for a given day are cumulative.

BUTTE LAKE TO BUMPASS HELL

The first trek explores the park from its northeast corner to its southwest corner and requires two cars, one parked at the Bumpass Hell parking lot and the other at Butte Lake. These directions describe the route starting at Butte Lake and ending at the Bumpass Hell parking lot, but you may want to hike it in reverse.

Day 1: Butte Lake to Warner Valley

See Transportation for driving directions. Signage on the park’s trails is generally excellent.

Hike Nobles Emigrant Trail from the western tip of Butte Lake to Cinder Cone. 1.2 miles

Continue to Rainbow Lake. 4.4 miles

Hike to Lower Twin Lake and the PCT. 5.2 miles

Turn left and take the PCT to Swan Lake. 5.7 miles

Hike to Corral Meadow Junction along Grassy Swale. 10.1 miles

Continue on the PCT to Warner Valley and Drakesbad Guest Ranch. Leave the PCT at the Warner Valley Campground, turn right, and continue on the park road 0.5 mile until it ends at Drakesbad.

total miles 12.5

Day 2: Warner Valley to Bumpass Hell

Return to the Warner Valley Campground. Pick up the PCT next to site 7 and ascend out of Warner Valley to the junction of the trail to Kings Creek Falls. 1.5 miles

Take the left fork, leaving the PCT, to Bench Lake. 3.1 miles

Continue to Kings Creek Falls. 4.1 miles

Follow the trail upstream. The trail divides into an equestrian trail to the right and the hiking trail along the cascading creek to the left. Follow the trail to Upper Meadow. 5.2 miles

Ramble through the meadow on the north side of the road to Kings Creek picnic area. 6.2 miles

Find the trailhead to Bumpass Hell at the picnic area parking lot. Hike to Bumpass Hell. 8.9 miles

Continue to Bumpass Hell parking lot.

total miles 10.1

SUMMIT LAKE LOOP VIA WARNER VALLEY

The second trek explores the central park, a mountainous land of forests, lakes, and streams. A 19.4-mile loop, it starts and ends at Summit Lake with a stopover at Drakesbad Guest Ranch.

Day 1: Summit Lake to Warner Valley

See Transportation for driving directions. Hike the boardwalk from the ranger station parking area to the northeast corner of Summit Lake. Follow the trail on the east side of the lake to the junction. Signage on the park’s trails is generally excellent.

Turn left on the trail to Echo Lake and Twin Lakes. Hike from Summit Lake to Echo Lake. 2.1 miles

Continue to Upper Twin Lake. 3.3 miles

Follow the trail along the north shore of Upper Twin Lake to the southwest end of Lower Twin Lake. Take the right fork of the trail around the south shore of Lower Twin Lake to the PCT. 4.2 miles

Turn south on the PCT to Swan Lake. 4.7 miles

Continue to the Corral Meadow junction along Grassy Swale. 8.7 miles

Continue on the PCT to Warner Valley and Drakesbad Guest Ranch. Leave the PCT at the Warner Valley Campground, turn right on the park road, and continue 0.5 mile until it ends at Drakesbad.

total miles 11.1

Day 2: Warner Valley to Summit Lake

Return to the Warner Valley Campground. Pick up the PCT next to site 7, and ascend out of Warner Valley to the junction of the trail to Kings Creek Falls. 1.5 miles

Take the left fork, leaving the PCT, to Bench Lake. 3.1 miles

Continue to Kings Creek Falls. 4.1 miles

Follow the signs toward Corral Meadow, hiking downstream on Kings Creek Trail to the trail junction to Summit Lake. 6.1 miles

The junction to Summit Lake is near the confluence of Kings and Summit Creeks. Turn left and ascend to the Summit Lake South Campground. The trail enters the camp between sites E10 and E11. Hike through the campground in a northerly direction toward Summit Lake. Find the trail between sites C8 and C9. Follow the signs to the amphitheater around the east side of the lake. Follow the trail and boardwalk to the ranger station, the overnight parking area, and your car.

total miles 8.6

TRANSPORTATION

Public Transportation

UNFORTUNATELY, THERE IS NO PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION to Lassen Volcanic National Park. A Greyhound bus goes from Reno to Susanville three times a week, but a taxi ride to and from the park is prohibitively expensive. It would be much less expensive to rent a car.

Driving Directions: Butte Lake to Bumpass Hell

THIS WALKABOUT REQUIRES TWO CARS, one parked at the Bumpass Hell parking area and the other at Butte Lake. The walkabout can be made in either direction. CA 89 winds through the park’s western half. The Bumpass Hell parking lot is 6.4 miles north of the southwest entrance station. After parking one car, drive north on CA 89 through the park, exiting its northwest corner. Continue on CA 89 to CA 44, and turn east. Eleven miles from the junction of CA 89 and CA 44, turn south on Forest Service Road 32N21. Look for the sign to Butte Lake. Drive several miles on the well-graded gravel road, and proceed through the campground to the end of the road at the northwest end of the lake, where you will find the trailhead.

Driving Directions: Summit Lake Loop via Warner Valley

SUMMIT LAKE IS 17.5 MILES NORTH of the southwest entrance to the park on CA 89 and 12 miles south of the northwest entrance. To park overnight, drive 0.3 mile north of the entrance to the North Summit Lake Campground. Turn right toward the ranger station to the parking area at the end of the road.

MAPS

THE LASSEN VOLCANIC NATIONAL PARK WEBSITE (nps.gov/lavo) provides a free downloadable map that is also available at the park entrance. Wilderness Press’s Lassen Volcanic National Park ($7.46) covers the park plus Bucks Lake, Caribou, and Thousand Lakes Wilderness. Visit wildernesspress.com to order.

The U.S. Geological Survey sells topographical hiking maps and provides free downloadable maps at store.usgs.gov, and go to the map locator. For Butte Lake to Bumpass Hell, you’ll need Prospect Peak (Butte Lake area), Mount Harkness (Twin Lakes area), and Reading Peak (Warner Valley and west). For Summit Lake Loop via Warner Valley, you’ll need Reading Peak.

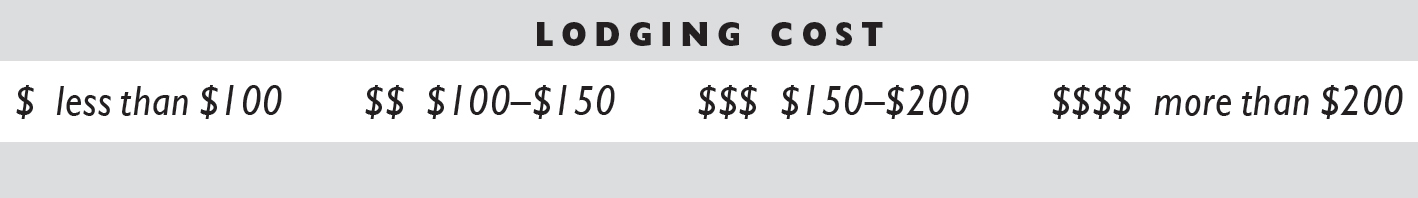

PLACES TO STAY

DRAKESBAD GUEST RANCH $$$–$$$$ • End of Warner Valley Road • 17 miles outside Chester • 866-999-0914 (reservations) • 530-529-1512 • drakesbad.com • Three meals included. Hot-springs pool, horse rides, fly-fishing, and massage.