Devil’s Slide

San Francisco to Half Moon Bay

To me the sea is a continual miracle,

The fishes that swim—the rocks—the motion of the

waves—the ships with men in them,

What stranger miracles are there?

—WALT WHITMAN, “Miracles”

Devil’s Slide

He walked and he walked, and the earth and the holiness of the earth came up through the soles of his feet.

—GRETEL EHRLICH, Legacy of Light

THIS EASY FOUR-DAY, 30-MILE WALKABOUT from Ocean Beach in San Francisco to Half Moon Bay starts with an 8.9-mile hike along the beach, climbs the flank of Montara Mountain, follows the cliffs above Fitzgerald Marine Reserve, and ends with a stroll on Half Moon Bay State Beach. Along the way, you will visit coastal villages with fine dining and entertainment. The coast of San Francisco and San Mateo Counties is extraordinarily wild for being so close to urban centers. Take a multiday walkabout and immerse yourself in its power and beauty.

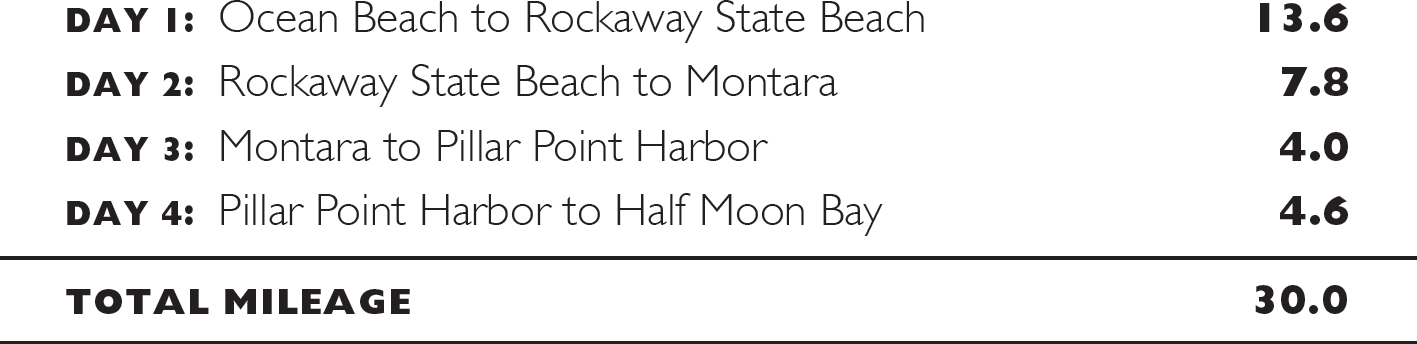

ITINERARY

THE VIEW FROM SUTRO HEIGHTS PARK is a classic San Francisco vista. The vast Pacific stretches out before you, the horizon interrupted on a clear day only by the Farallon Islands, ancient mountain peaks jutting out of the sea 27 miles offshore. To your right, the steep, forested hills of the Marin Headlands climb abruptly from the narrow channel of the Golden Gate. The rugged Marin Coast extends north to the cliffs of Point Reyes. The Cliff House (in its third incarnation) lies below.

Originally a modest white clapboard house built in 1863 and then rebuilt as a Victorian pleasure palace in 1896, it served San Franciscans who traveled from the east side of the peninsula across empty sand dunes for a day at the beach. The first two structures were destroyed by fire; the third was built in 1909. To the south, two windmills rise out of the forests of Golden Gate Park. Built in 1903 and 1908, they pumped subterranean water to irrigate the 1,017-acre park. Ocean Beach, broad and flat, beckons, stretching as far as you can see and disappearing into the mist.

You may want to stop for breakfast at Louis’, a favorite San Francisco eatery known for its conviviality and spectacular setting on the cliffs at the edge of the continent. Cantankerous sea lions bark from Seal Rock just offshore. Lands End and the ruins of Sutro Baths lie below. Built in 1896 by San Francisco entrepreneur and former mayor Adolph Sutro, it was the largest indoor swimming structure in the world, with seven fresh- and saltwater pools, an ice-skating rink, a museum, and a concert hall. Fire destroyed it in 1966. Enjoy your meal while watching massive freighters glide in and out of the Golden Gate.

San Francisco’s Cliff House

Day 1: Ocean Beach to Rockaway State Beach

I STARTED THIS WALKABOUT ON A WARM, sunny October morning. Spring, from mid-April to June, and fall, from September to mid-November, are prime hiking times on the Northern California coast, offering the best chances to avoid the winter rains and the summer fog. Autumn hiking has another advantage; the ocean has had all summer to warm up. Although the waters off the coast are never balmy, this is the best season for a swim.

I arrived at Ocean Beach midmorning, 15 minutes after high tide. The sand at the shoreline was soft, but as the day progressed, the tide receded and the sand became firm. One of the best hiking beaches I know, Ocean Beach is flat with solid footing and stretches for 9 uninterrupted miles. The hours before and after low tide are usually the best for beach walking; tide schedules can be found at tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov/tide_predictions.

A very high tide will sometimes block the last section of this 9-mile beach hike. Play it safe, and plan to arrive at Mussel Rock at least 2 hours before or after high tide.

Ocean Beach can be wild on weekends, with surfers, joggers, dogs, kites, Frisbees, windsurfers, kids playing in the cool waters, and families building sand castles. Weekdays are much quieter. A concrete seawall separates the wide beach from the Great Highway, and the forests and windmills of Golden Gate Park peek over it. After a few miles, sand dunes replace the seawall, framing the eastern edge of the beach. The dunes block the view of civilization, and the only sounds are the breeze and the roar of the mighty Pacific. As you hike south, the number of people dwindles to only a few fellow walkers and a handful of people fishing for striped bass and ocean perch.

The Pacific feels immensely powerful. On this October morning, the 10-foot waves were fairly fierce. Mist spun in the air as they crested and crashed. Walking on the ocean’s edge, you feel connected to its other shores. Have you strolled on a beach in Hawaii or on the west coast of Mexico or South America? Perhaps you have waded in the warm waters off Japan or Southeast Asia. The world is vast, connected, and mostly water. Walk the shoreline of the Pacific Ocean from high tide to low, and feel the ancient rhythms of pounding waves and the cyclical pull of the moon. Your pace slows. There is no hurry. With 13 miles to hike, you can take a swim, stop for lunch, have a nap, and still arrive before dinner.

Although your walk feels so calming, never turn your back on the unpredictable ocean. A rogue wave can soak your shoes, and unsuspecting beachcombers have been swept out to sea along this beach. If you swim, stay close to shore and don’t swim alone. Riptides can be swift and dangerous.

Ocean Beach

After 3.6 miles, the dunes rise, the Great Highway turns inland, and a trail leads up to Fort Funston. Originally built during World War I to defend the entrance to San Francisco Bay from enemy ships, it continued its role through World War II. A Nike missile base during the early Cold War, it was decommissioned in 1963. Today it is part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. You may want to leave the beach and enjoy the views from the cliffs. The Fort Funston Trail climbs and follows an old asphalt road to the Environmental Education Center, where a trail returns to the beach. The fort is a favorite spot for hang gliders, as offshore breezes strike the cliffs, causing updrafts. If you continue hiking on the shore, you are likely to see them floating on the wind and landing on the beach.

Fort Funston marks the border of San Francisco and San Mateo Counties. The worn sandstone cliffs climb to 400 feet. You can expect to have the beach pretty much to yourself south of the fort. The San Mateo County coast is mostly open space, which is extraordinary because of its proximity to San Francisco. In the early 1900s the owners of the Ocean Shore Railroad set out to build a rail line from Santa Cruz to San Francisco along the coast. The 1906 earthquake and the financial panic of 1907 prevented their dream from becoming a reality, but sections of the line operated between 1905 and 1920. Part of the dream was to develop the San Mateo County coast into “the Coney Island of the Pacific.” We are fortunate they failed.

The beach ends abruptly at 8.9 miles in a jumble of large boulders just before Mussel Rock. The offshore rock with a metal structure on top is unmistakable. Scramble over boulders on an informal path, and ascend the gravel roads and trails to the Mussel Rock parking area.

Follow the directions in The Route, for the trail through Pacifica. It takes you along Esplanade Avenue where apartment buildings cling to the edge of the high cliffs. Winter storms in 2009 caused the saturated bluff to collapse. Apartment balconies once 20 feet from the cliffs were now suspended over open space. A few buildings were condemned, but apartment owners drilled long steel tubes into the sheer sandstone cliffs to shore up others and to drain excess water. El Niño storms of 2016 finished the job, and buildings were demolished. The San Andreas Fault turns out to sea just north of Pacifica and comes back to land in Marin County. It is only a matter of time before the powerful forces of winter storms and violent earthquakes send nearby apartment buildings into the sea.

Our trail returns to the shore at Sharp Park Beach, and you reach the municipal pier at 11.7 miles. The paved promenade is a great place for people-watching. The trail follows the seawall, which turns from concrete to earthen, separating the ocean from Sharp Park and Laguna Salada, a freshwater lagoon and marsh. Mori Point is a massive rock that separates Sharp Park Beach from Rockaway State Beach to the south. It rises 400 feet and extends into the sea, ending in a string of battered sea stacks.

Hiking south from Fort Funston

The trail turns inland at the base of Mori Point, crosses an arm of the Laguna Salada marsh, and continues to CA 1. Follow the paved hiker/biker trail along the highway 0.2 mile until it turns to the back side of Mori Point and passes through wetlands and a pampas grass forest taking you into Rockaway State Beach, where you will find restaurants and inns.

I continued another 0.9 mile to the Pacifica Beach Hotel. A soak in their Jacuzzi bathtub with the sound of the waves pounding outside your balcony is a great way to end a day of hiking. The first day’s 14.5-mile stroll along the coast took me a leisurely 7 hours.

The neighboring restaurant, Puerto 27, was quiet that evening, and I dined at the bar on a rich Peruvian paella, salad, and a glass of pinot grigio while watching the National League playoffs. The bartender, Paul, was from Thailand, slightly graying with a big smile and a gentle voice. He had been a monk before he came to California 30 years ago. As a Buddhist, he still meditates daily. I forgot about the game as we talked for a few hours about Buddhism and Christianity, the spiritual and psychic benefits of meditation and walking, and of life in Thailand and the United States. He was excited about hiking inn to inn. “Breathe deeply as you walk. If you are a Christian, breathe in thinking, ‘Jesus.’ Breathe out, ‘Christ.’ You will feel connected to the earth and to God.”

Day 2: Rockaway State Beach to Montara

IN THE MORNING I RAN INTO PAUL on my way to get coffee. He said, “Remember to breathe while you walk and think, ‘It is a great day to be alive.’ ” We stood in the parking lot and shared a few deep breaths of the cool ocean air. It was truly a great day to be alive.

Leaving Rockaway State Beach, follow the paved hiker/biker trail to Pacifica State Beach, and cross back to the east side of the highway at Linda Mar Boulevard. Montara, our destination for Day 2, has limited dining options. You can pick up supplies at the Linda Mar Shopping Center, and the Point Montara Hostel has a nice kitchen where you can prepare meals.

Walk 0.1 mile on the hiker/biker trail on the side of the highway across San Pedro Creek. The trail turns inland to skirt the next stretch of the coast, named Devil’s Slide. The highway once wound along sheer cliffs, and some motorists who stopped concentrating for a moment perished on the rocks hundreds of feet below. Landslides periodically close the road. A pair of tunnels, dug through the mountain, replaced this dangerous stretch in 2013, and the old section of CA 1 has been converted to a 1.3-mile hiking trail with breathtaking views of the wild Pacific crashing on steep cliffs.

Our trail follows the San Pedro Creek Valley before ascending the flank of Montara Mountain. It was along the San Pedro where in 1769 Gaspar de Portolá encountered an Ohlone village and then made an amazing discovery. Based on journals from the Portolá expedition and the wonderful classic, The Ohlone Way, by Malcolm Margolin, as I hiked along San Pedro Creek, this is the way I imagine that first encounter 250 years ago:

Morning in the village began as it had for hundreds of years. The villagers rose before dawn, faced the east, and shouted greetings and exhortations to the sun, who once again listened and rose. Many of the men had beards and moustaches. They wore stone and shell amulets. Otherwise they were naked. The women wore deerskin or tule reed skirts and necklaces made of shells and feathers, their chins tattooed with lines and dots. Children played while babies were bound tightly in woven cradles near their mothers’ sides.

The village of 200 was enjoying the season’s bounty. Acorn gathering was just completed, and their stores held enough for the next year. The shaman’s dance and song had drawn a whale to the shore, and they had feasted for days, storing blubber in baskets and drying strips of flesh on high branches beyond the reach of grizzlies. The village, near where the river meets the sea, was blessed with year-round abundance. Vast schools of smelt ran for days and filled nets to overflowing. Soon steelhead would flood the stream, and their dried and smoked flanks would be savored for months. Herds of deer, elk, and antelope roamed the hills and savannahs. And always, oysters, clams, and mussels were easily harvested.

This day would not end as others had. Word had reached the village that a party of strangers was headed their way. Captain Gaspar de Portolá, Spanish governor of Las Californias, was leading a party of 62 soldiers, priests, and Indian servants, along with 200 horses and mules. They had marched from Baja to San Diego, where Portolá left Father Junipero Serra behind to establish the first California mission. Portolá and his party then marched north to find Monterey Bay, the “protected harbor” that Sebastian Vizcaíno had discovered and praised 150 years earlier. They hiked up the coast but had to turn inland to get around the rugged Santa Lucia Mountains of Big Sur. Reaching the upper Salinas Valley in late September, they followed the Salinas River downstream and back to the coast. Failing to recognize Monterey Bay because of fog and because it was nothing like the snug harbor Vizcaíno had described, they continued north.

By the time the party reached San Pedro Creek, they had battled bad weather and were suffering from hunger and scurvy. The Ohlone greeted them with the usual hospitality of Bay Area natives—gifts of deer, elk, and shellfish. Portolá’s party gratefully made camp across the river from the village.

That afternoon, Sergeant Ortega led a small hunting party into the hills. They climbed to what today is called Sweeney Ridge. Looking down to the east, they saw grassy savannahs, dark stands of oak trees, and creeks flowing into “an immense arm of the sea,” with vast marshlands bordering its shore. On November 4, 1769, the entire party climbed the ridge—the first Europeans to view the San Francisco Bay. Father Juan Crespi called it “this most noble estuary.” Descending to what is now Menlo Park, they explored the southwest shore of the bay for several days.

The party of strangers returned to the Ohlone village but soon departed for San Diego. The following summer, word reached the villagers that Portolá had come back to the land of the Ohlone, this time with the priest, Junipero Serra. On June 3, 1770, Portolá claimed the land for Spain. A presidio and mission were established in Monterey. The era of enslavement and destruction of the Bay Area’s native peoples had begun.

Leaving San Pedro Creek, take a short walk through the Linda Mar neighborhood, and climb Higgins Road to just beyond where the houses stop. Pass through a gate onto the Old San Pedro Mountain Road. Now a wilderness trail, it was once a wagon road that climbed the mountains to avoid the impossible cliffs of Devil’s Slide. Before that, it was most likely an Indian trading route. A chronicler from the Portolá party described it as “a very bad road up over a high mountain” that “though easily climbed on the way up, had a very hard abrupt descent on the opposite side.”

Ascend through Monterey pine and eucalyptus forests before emerging into open coastal hills dense with sage and coyote brush and spotted with mimulus, Scotch broom, hemlock, ceanothus, sweet peas, and pampas grass—the views are spectacular. Turn a corner and see the vast blue Pacific extending to the horizon. Turn again and see the soaring coastal mountains. This trail is often the dividing line between sunshine and fog. Morning clouds gradually burn off, and you are bathed in warm sunlight. Fingers of fog return in the late afternoon, drifting in to fill valleys and then blanket the peaks.

The trail passes between San Pedro Mountain at 1,050 feet and Montara Mountain at 1,898 feet. There are benches at overlooks where you can enjoy a rest. Crossing the Montara Mountain Trail at 4.1 miles, you may want to take a side trip up the mountain to enjoy the views.

There are dozens of side trails made by mountain bikers along the descent to the coast. The main trail drops down through McNee State Park to CA 1, north of Montara. Hike 0.1 mile along the highway shoulder, cross the highway into a parking area, and take the stairs to Montara State Beach. Hike south to the end of the beach 0.5 mile and then into town.

Walk down Main Street, which becomes a footpath, to get to the Point Montara Lighthouse Hostel. Perched on a point, it is one of a series of Hostelling International USA hostels set in amazing locations along California’s coast. Rooms overlook the rugged coastline and Devil’s Slide to the north. There is a large communal kitchen and a small coffeehouse. A dormitory bed costs only $32 a night. My wife, Heidi, joined me that evening for the last two days of the walkabout. We had a simple private room in a truly spectacular setting for $88. That evening we cooked dinner and shared a meal with travelers from around the globe. Montara has a small convenience store and a few small restaurants if you are not preparing food at the hostel.

Day 3: Montara to Pillar Point Harbor

THE THIRD LEG OF THIS WALKABOUT is short, just 4 miles, but the coastline is beautiful, the tide pools of the Fitzgerald Marine Reserve are fascinating to explore, and a restaurant on the bluffs above the Pacific is a wonderful spot for a long lunch. You may want to combine the last two days of this walkabout and hike 8.6 miles from Montara to Half Moon Bay, but spending a leisurely day exploring the coast between Point Montara and Pillar Point is a delight.

The hike starts by leaving the south end of Montara and strolling through the coastal neighborhood of Moss Beach (see The Route, for detailed directions). After 0.5 mile you reach an open space along the bluffs with benches overlooking the crashing waves relentlessly pounding offshore rocks—a nice place to pause and take in the beautiful scene. Our route leads back to CA 1, where you take an immediate right on California Avenue and walk a few blocks until it ends at the entrance to the James V. Fitzgerald Marine Reserve. The reserve and intertidal reefs extend from just south of Point Montara to Pillar Point. A small ranger station at the end of California Avenue has information about the reserve. Turn right and walk one block to take a side trip to the beach.

Low tides expose an intricate web of tide pools. We saw green anemones, orange sea stars, and crabs. Harbor seals frolicked just outside the exposed reef and stopped to watch us watching them. Lines of brown pelicans glided past, almost skimming the waves. A snowy egret landed gracefully on the reef and stepped gingerly, staring into the water. Quickly her head darted and her long beak plunged into a pool, skewering a tasty morsel. Cormorants and grebes floated in the protected open water, periodically diving for a fish. Curlews probed the shoreline with long, curved beaks, searching for crustaceans and insects.

Return to the end of California Avenue to continue south on the trail. Cross the metal footbridge, and follow the path up to the coastal bluffs. The trail passes through a forest of stately Monterey cypress. As we hiked, the rays of the morning sun pierced the cypress canopy as though shining through the high windows of an ancient cathedral. Harbor seals napped below on the reef. As the tide receded, they galumphed across the rocks and into the sea to swim to a newly exposed shelf farther offshore for a peaceful snooze with greater protection.

The trail ends and you briefly stroll through the neighborhood to the Moss Beach Distillery restaurant. We stopped for the best meal of the trip, a lunch on the sunny patio of fried shrimp, steamed clams, and beer. Harbor seals played below the cliffs in the clear waters of a protected cove.

The restaurant opened in 1927 as Frank’s Place, a well-known speakeasy during Prohibition. Canadian rumrunners docked below and unloaded supplies that were hauled up the cliffs and quickly transported to San Francisco. Some of the bounty stayed behind for local enjoyment. Throughout the years, “The Blue Lady,” an unfortunate victim of a love triangle involving a handsome piano player and a jealous husband, has haunted the restaurant. They say her spirit remained behind to cherish the good times she had before her untimely death.

Leaving the restaurant, take Ocean Boulevard from the parking lot. The first section of the road is closed to traffic. It is a joyful hike over a roller-coaster road, tossed and buckled by shifting coastal bluffs. You soon reach open space. Take the trails along the bluffs to Pillar Point. The end of the point is fenced off for an Air Force tracking station, but a trail on the north side descends the cliffs to the beach, where you may want to enjoy more tide pooling along the reef.

The world-famous Mavericks surf break lies 0.5 mile offshore. The seafloor forms a long, sloping ramp that slows and builds the swells. Winter waves can reach heights of 50 feet. Since 1999 big-wave surfers from around the globe have gathered to ride these enormous waves in an invitation-only surfing contest, one of the most dangerous in the world.

The stormy seas north of the peninsula are in sharp contrast to the calm protected waters to the south. Pillar Point forms the northern tip of Half Moon Bay. The peaceful Pillar Point Harbor and Princeton-by-the-Sea lie below. Take the road down from the point, and stroll along the beach into town, where you will find inns, restaurants, bars, and a lively nightlife. The Half Moon Bay Brewing Company and the Old Princeton Landing offer live music and dancing on the weekends.

Hiking to Montara Mountain

Day 4: Pillar Point Harbor to Half Moon Bay

THE BAY FORMS A LONG, GRACEFUL ARC. You can walk the beach or the paved hiker/biker trail along the low bluffs. A favorite spot for a day at the beach and for surfing lies just beyond the southern breakwater of Pillar Point Harbor. Sweetwater Camp, at 2.4 miles, sits on the bluff at the edge of Frenchman’s Creek, sheltered by Monterey pines. Frenchman’s and Pilarcitos Creeks, the latter at 2.7 miles, may flow to the sea, depending on the winter rains. You can leave the beach and take the paved trail to cross them.

As we hiked along the bay, I thought of my Thai monk friend, Paul, who said, “You are walking the beach? You must take off your shoes when you walk and feel the connection to the earth.”

We removed our shoes, forded the creek, and continued along the beach to Francis Beach Campground and the Half Moon Bay State Beach office at 3.7 miles. Turn inland and take Kelly Avenue another 0.9 mile into downtown Half Moon Bay.

This four-day hike provides a deep connection to the Pacific Ocean along its beaches, bluffs, and coastal mountains, through wilderness and small towns. Take a walkabout and breathe in the beauty, history, and wildness of the Pacific Coast from San Francisco to Half Moon Bay.

Mori Point

THE ROUTE

All mileages listed for a given day are cumulative.

Day 1: Ocean Beach to Rockaway State Beach

For directions to Ocean Beach, see Transportation. This day’s hike starts with an 8.9-mile stroll on the beach. Time your hike with the outgoing tide. The hours before and after low tide are best for hiking—wide beaches with firm sand. Consult tide schedules at tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov/tide_predictions. Walk down the sidewalk from the Cliff House to Ocean Beach, and head south.

Walk along Ocean Beach to Fort Funston. 4.5 miles

Continue on the beach to Mussel Rock. 8.9 miles

The beach ends at a jumble of large boulders. The approach to Mussel Rock beach can be blocked by high tides, so plan to arrive at least 2 hours before or after high tide. Scramble up the informal path over rocks, and walk the gravel road that parallels the shore for 200 yards. Turn left on another gravel road, and climb. Take the path to the Mussel Rock City Park parking area. 9.1 miles

Continue on the road south from the parking area, Westline Drive to Palmetto Avenue, and turn right. 9.5 miles

Turn right on Esplanade Avenue. 10.0 miles

Turn left on West Avalone Drive. 10.5 miles

Turn right on Palmetto Avenue and right on Paloma Avenue, and walk to the paved promenade along Sharp Park Beach to the Pacifica Pier. 11.7 miles

Continue south along the paved promenade and earthen seawall to the base of Mori Point, where the trail turns inland. Cross a marsh along a boardwalk, and turn right on Lishumsha Trail. Walk 200 yards and then turn left on Upper Mori Trail. When you reach the road, turn right and follow the paved hiker/biker trail along CA 1 for 0.2 mile until it leaves the highway and travels through a pampas grass field on the back side of Mori Point to Rockaway State Beach.

total miles 13.6

Day 2: Rockaway State Beach to Montara

Hike south along the paved hiker/biker trail to Pacifica State Beach. 0.9 mile

Cross CA 1 at Linda Mar Boulevard and walk the hiker/biker trail on the eastern side of the highway 0.1 mile across San Pedro Creek. Follow the trail inland along the creek as it merges with San Pedro Terrace Road. Turn right on Peralta Road, and continue until it ends. Pass through a wooden gate, and walk a short path and up Higgins Way to the gate that marks the beginning of Old San Pedro Mountain Road. 2.2 miles

Continue to the intersection of the Montara Mountain Trail. 4.1 miles

Continue on the Old San Pedro Mountain Road to CA 1. 6.8 miles

Hike south along the highway shoulder 0.1 mile, cross the highway at the parking area, and take the stairs to Montara State Beach. 7.0 miles

Hike to the end of the beach, and climb to the parking area. Cross the highway, take Second Street inland, and turn right on Main Street. To reach Point Montara Hostel, walk to the end of Main Street, and continue on the path to 16th Street. The hostel is across the highway.

total miles 7.8

Day 3: Montara to Pillar Point Harbor

Leaving the Montara Hostel, follow the frontage road along a chain-link fence until it ends. Take the path, and continue on Vallemar Street. Turn right on Juliana Avenue until it reaches CA 1 and California Avenue. Take an immediate right on California Avenue, and walk a few blocks until it ends. Cross the metal bridge, take the path through the Monterey cypress forest to the trail along the coastal cliffs, and head south. The trail ends at Beach Way. Follow it along the coast to the Moss Beach Distillery restaurant. 1.7 miles

Take Ocean Boulevard from the restaurant parking lot until it ends. Follow the trail along the bluffs toward Pillar Point. The end of the narrow point is fenced off for an Air Force tracking station. Turn left on the road off the point, and take the path to the beach and to Pillar Point Harbor.

total miles 4.0

Day 4: Pillar Point Harbor to Half Moon Bay

Hike along the waterfront to the breakwater at the end of Pillar Point Harbor. Follow the shore on the beach or on the trail along the bluffs to Francis Beach Campground and the Half Moon Bay State Beach office. 3.7 miles

Turn inland on Kelly Avenue. Walk to CA 1 and into downtown Half Moon Bay.

total miles 4.6

Cypress forest at Fitzgerald Marine Reserve

TRANSPORTATION

Public Transportation

TO REACH OCEAN BEACH and the start of this walkabout, take BART to the Embarcadero Station in San Francisco. Walk up Market Street two blocks to Fremont Street and take Muni Bus 38R ($2.75) to Sutro Heights at the end of the line.

To return from Half Moon Bay to downtown San Francisco, go to 511.org to plan your journey ($10.75). Go to samtrans.com for more information on Samtrans schedules.

Flying into the Bay Area

FROM SFO TAKE BART to San Francisco’s Embarcadero Station ($8.95), and follow the public transportation directions above. From the Oakland International Airport, take the Oakland Airport BART to the Oakland Coliseum BART Station. Take BART to San Francisco’s Embarcadero Station ($10.20), and follow the public transportation directions above.

MAPS

THE U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY sells topographical hiking maps and provides free downloadable maps; visit store.usgs.gov, and go to the map locator for the following: San Francisco South, 2015 ($15); Montara Mountain, 1997 ($8); Half Moon Bay, 2015 ($15), all 7.5-minute. A good road map of the Bay Area might also be sufficient.

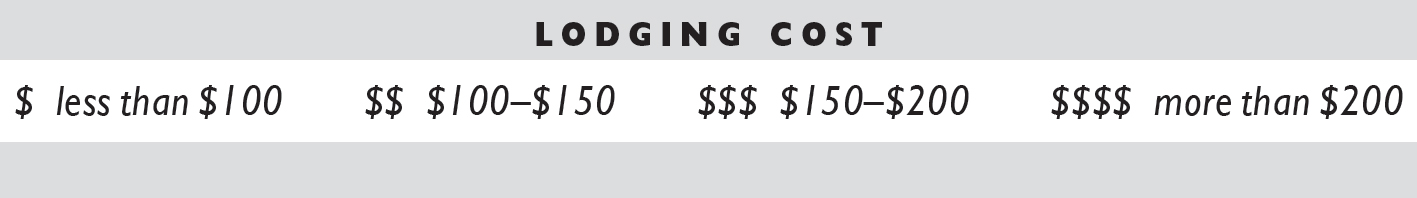

PLACES TO STAY

San Francisco

There are scores of hotels in San Francisco. This one is very close to the start of the walkabout.

SEAL ROCK INN $$–$$$ • 545 Point Lobos Ave. • 415-752-8000 • sealrockinn.com

Pacifica: Rockaway Beach

INN AT ROCKAWAY $$–$$$ • 200 Rockaway Beach Ave. • 650-359-7700 • 800-522-3772 • innatrockaway.com

NICK’S RESTAURANT AND SEA BREEZE MOTEL $$ • 100 Rockaway Beach Ave. • 650-359-3903 • nicksrestaurant.net • Live music in the restaurant on the weekends.

LIGHTHOUSE HOTEL $$$–$$$$ • 105 Rockaway Beach Ave. • 650-355-6300 • pacificalighthouse.com • Live music in restaurant on weekends.

Pacifica: Pacifica State Beach

PACIFICA BEACH HOTEL $$–$$$$ • 525 Crespi Dr. • 650-355-9999 • pacificabeachhotel.com • Jacuzzi bathtubs.

Montara

POINT MONTARA LIGHTHOUSE HOSTEL $ • 16th St. and CA 1 • 650-728-7177 • hiusa.org

Moss Beach

If you wish to hike 1.5 miles beyond Montara, follow The Route south into the Fitzgerald Marine Reserve. The bluff trail through the Monterey cypress grove ends at Cypress Ave. Turn left, and continue two blocks to reach this lovely, secluded inn.

SEAL COVE INN $$$–$$$$ • 221 Cypress Ave. • 650-728-4114 • sealcoveinn.com

Pillar Point Harbor

OCEANO HOTEL AND SPA $$$$ • 280 Capistrano Road • 650-726-5400 • oceanohalfmoonbay.com

INN AT MAVERICKS $$$$ • 346 Princeton Ave. • 650-421-5300 • innatmavericks.com

Half Moon Bay

NANTUCKET WHALE INN $$$–$$$$ • 779 Main St. • 650-726-1616 • nantucketwhaleinn.com

COASTSIDE INN $$-$$$$ • 230 Cabrillo Hwy. • 650-726-3400 • coastsideinn.com

HALF MOON BAY INN $$–$$$$ • 401 Main St. • 650-726-1177 • halfmoonbayinn.com

Point Montara Lighthouse Hostel