Hiking the Sierra Crest

HIKING THE TAHOE BASIN

Donner Pass to Lake Tahoe

Each day is a journey, the journey itself home.

—MATSUO BASHO, The Narrow Road to the Deep North

Hiking the Sierra Crest

The earth never tires,

The earth is rude, silent, incomprehensible at first,

Nature is rude and incomprehensible at first,

Be not discouraged, keep on, there are divine things well envelop’d,

I swear to you there are divine things more beautiful than words can tell.

—WALT WHITMAN, “Song of the Open Road”

WITH THE TRUCKEE RIVER VALLEY TO THE EAST, the deep gorge of the American River Canyon plunging to the west, and Lake Tahoe shimmering in the distance, this walkabout follows the spine of the High Sierra along the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT). A challenging 30-mile trek spread over three hiking days, it has two steep descents and one ascent of 1,900 feet. You’ll be rewarded with stopovers at mountain resorts in spectacular settings and the solitude and pristine beauty of the Sierra Nevada.

Traverse 18.5 miles of the Pacific Crest Trail on this walkabout.

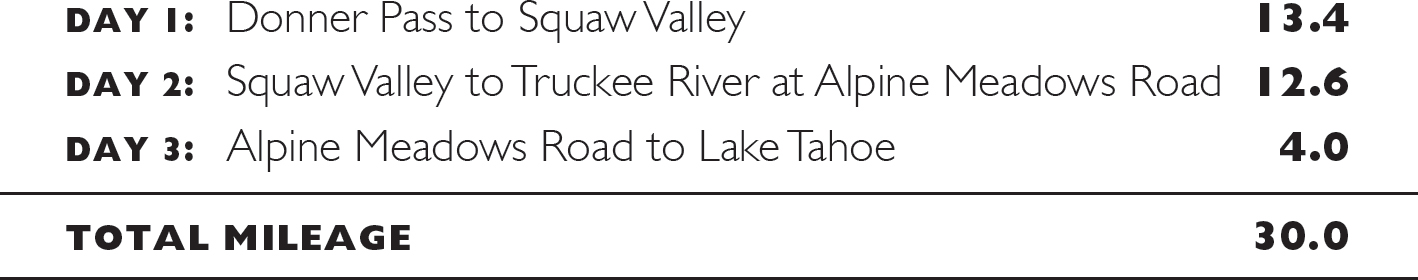

ITINERARY

Day 1: Donner Pass to Squaw Valley

THE TRAIL STARTS AT DONNER PASS (7,100') and climbs sharply along a series of rocky switchbacks, but soon it levels off for a long, gradual ascent. You are hiking on the PCT. Stretching 2,650 miles from the US–Mexico border near Campo, California, to 9 miles into British Columbia’s Manning Provincial Park, it follows the crest of the Sierra Nevada and the Cascade Range. On this walkabout you will hike 18.5 spectacular miles of the PCT.

My friend Scott and I set out at dawn in the first week of October. With only 11.5 hours of daylight, we wanted to get an early start. A storm had swept through the Northern Sierra the week before, the remnants of a typhoon that had hammered the Philippines. It dropped several inches of snow, but most of it had melted. Patches of ice and snow remained in the shadows. Frozen earth crunched underfoot, and snow graced the high peaks. The air was crisp and fragrant with the smell of pines.

The trail rises along the west side of the ridge, shaded from the early morning sun. Lake Mary lies below, and soon the high mountains that form Sugar Bowl Ski Resort come into view. Hike below a chairlift and past the turnoff to Mount Judah at 2.1 miles. With a short side trip, you can easily reach its summit of 8,243 feet. Continue on the PCT, ascending until you reach Roller Pass, an open ridge at 2.4 miles. A metal sign marks the spot where a portion of the ill-fated Donner Party crossed this pass: WE MADE A ROLLER AND FASTENED CHANS TO GETHER [SIC] AND PULLED THE WAGONS UP WITH 12 YOKE OXEN ON THE TOP AND THE SAME AT THE BOTTOM.—NICHOLAS CARRIGER, SEP 22, 1846.

Roller Pass marks the most difficult barrier that the party faced on its journey to California. Emigrant Canyon plunges 1,500 feet, and they had to winch their wagons up the final ascent. Spectacular views of Donner Lake and the meadows north of Truckee now open to the east. To the southeast the PCT snakes along the rolling ridgeline for several miles on its way to Anderson Peak.

The first wagon train to cross these mountains, the Stevens Party, came in 1844, two years before the Donner Party and five before the gold rush. For each of the next four years, only a few hundred brave pioneers traveled overland to California. Mostly middle-class farm families, they fled malaria and the economic hard times of the Mississippi Valley for the promise of fertile land and a gentle climate. Pulled by teams of four to eight oxen, their prairie schooners were loaded with 1,500 pounds of supplies, enough for the 2,000-mile, four- to six-month journey. The wagons had no brakes or springs, and rather than endure the bone-jarring ride, most adults walked. Traveling at the speed of oxen, they averaged 14 miles per day across the plains and 10 miles in the mountains.

Leaving the Iowa or Missouri territories, wagon trains followed fur-trapper and Indian trading routes, crossing the prairie along the Platte River. There were vast herds of buffalo, and progress was easy across the open grasslands. As one early pioneer diarist described it:

Our camp this evening presents a most cheerful appearance. The prairie, miles around us, is enlivened with groups of cattle, numbering six or seven hundred, feeding upon the fresh green grass. The numerous white tents and wagon-covers before which the campfires are blazing brightly, represent a rustic village; and men, women, and children are talking, playing, and singing around them with all the glee of light and careless hearts. While I am writing, a party at the lower end of the camp is engaged in singing hymns and sacred songs.

Hearts became less “light and careless” as weeks passed and the wagons finally reached the Rockies, but this crossing was easy compared to the Sierra. Leaving the Platte, they followed the Sweetwater River in Wyoming, and after 900 miles, the trail rose gradually through a broad valley named South Pass. Early pioneers realized they had crossed the Continental Divide only when they noticed that streams now flowed west.

The trail divided, with some wagon trains heading north to Fort Hall in what today is Idaho, and others traveling south to the Great Salt Lake. Heading southwest, they converged along the Humboldt River. In 1844 the Stevens Party followed the Humboldt through the Great Basin until it ended abruptly, swallowed by the desert at the Humboldt Sink. They were uncertain which way to turn until they met an elderly Indian who drew a map in the sand and told them to head due west across 50 miles of desert. They would come to a great river with trees and good grass. His name was Truckee, and out of gratitude, they gave the river his name.

The Pacific Crest as seen from Roller Pass

After climbing the Truckee River Canyon and coming to Donner Lake, the wagon trains reached the Sierra Nevada and faced what looked like an impassable, ragged 1,200-foot granite wall. Finding passages for a man and a single ox, they coaxed the oxen to a plateau and yoked them into teams. Another team was assembled below. Long chains ran over large logs, or rollers, that worked as pulleys to haul up empty wagons—backbreaking work for man and beast.

A small book published in 1845, The Emigrants’ Guide to Oregon and California by Lansford W. Hastings, inspired the early pioneers to brave the uncertain journey. He described California as a paradise:

There is no country, in the known world, possessing a soil so fertile and productive, with such varied and inexhaustible resources, and a climate of such mildness, uniformity and salubrity; nor is there a country, in my opinion, now known, which is so eminently calculated, by nature herself, in all respects, to promote the unbounded happiness and prosperity, of civilized and enlightened man.

Hastings was an ambitious adventurer and opportunist who encouraged the United States to wrestle California from the weak and unstable control of Mexico. The Donner Party followed Hastings’s route in 1846, a “shortcut” to the Great Salt Lake that proved disastrous—impassable canyons and dense thickets of trees and brush that they had to laboriously clear with axes. A combination of incompetent leadership, poor decisions, and bad luck led the party to near starvation in the Nevada desert, every family fending for itself. When they reached the lake now called Donner, they confronted deep snow. Eighty members built cabins to wait for a break in the weather that never came. After eating the oxen and then the dogs, they reluctantly turned to cannibalism of those who had perished. Only 40 made it across the Sierra.

Hastings and his route were discredited. His “shortcut” was 120 miles longer and more treacherous than the earlier trail. Today a creek, pass, mountain, and lake bear the name of the Donner Party. The PCT now follows the crest, and it is one of the most beautiful trails I have hiked in the Sierra—exposed volcanic ridges, snowcapped peaks, scattered fir and pine forests, and deep gorges and canyons to the west and east. The bright-yellow flowers of mule’s ears cover mountain slopes in the spring. Now, in October, brown and brittle, they wait for their winter blanket of snow.

The PCT rambles along the rolling crest past Mount Lincoln (8,383') to Anderson Peak (8,683') at 5.1 miles. The path divides, with the left fork climbing to the peak and to the Benson Hut, a Sierra Club shelter for backpackers and skiers. Take the right fork, and circle the west side of Anderson Peak on a rocky trail carved out of boulders and scree. To the south and west lies the deep canyon of the North Fork of the American River.

Patches of snow settled in the trail’s depressions. We saw deer, rabbit, and bird tracks. For a 2-mile stretch, we followed the tracks of a lone coyote. There were no bootprints except ours.

View of Tinker Knob

The trail turns southeast and climbs a narrow ridge to the base of Tinker Knob (8,979'), the highest point on this walkabout. Here you can stop for a break with a view of the northern bay of Lake Tahoe, the town of Truckee to the northeast, and the American River Canyon to the southwest.

Scott said, “We are the only hikers to come here since last week’s storm, and another is headed this way on Sunday. I feel like we are putting this part of the Sierra and the Pacific Crest Trail to bed for the winter.”

Lake Tahoe, pale blue, sparkled in the autumn sunlight. Ten million years ago the immense pressure of the North American Continental Plate grinding over the Pacific Ocean Plate caused uplifts and folds, forming the Sierra Nevada and the Carson Range. The Tahoe Basin dropped between the two folds. Volcanic flows dammed the basin, and the great lake was formed. The Truckee River eventually cut through the volcanic deposits, giving the lake its only outlet.

At a depth of 1,645 feet, it is the second-deepest lake in the United States, after Crater Lake in Oregon. Glaciers dammed the Truckee both 2 million and 20,000 years ago, and the lake level rose 800 feet higher than it is today. When the glaciers receded the second time, the Truckee broke through and flowed again. Earthquake faults underlie the depths of the lake, and scientists predict tsunamis that can cross it in a few minutes. While you are enjoying a piña colada in one of Tahoe’s shoreline bars after your walkabout, you may want to consider the quake that formed McKinney Bay on the west side of the lake 50,000 years ago and set off a 330-foot tsunami. Cheers!

Cold Stream Trail meets the PCT under Tinker Knob at 7.8 miles. The Aram Party of 1846 spent three days searching for a better route over the Sierra than the cruel wall of granite at the west end of Donner Lake. They followed Cold Stream and discovered that, even though the pass was 700 feet higher, oxen teams could pull their wagons to within 100 feet of the ridge. Then, using rollers, they reached this junction. There was still a difficult week of mountain travel ahead of them before they would arrive at Sutter’s Fort, but they had conquered the most difficult barrier of their 2,000-mile journey.

Gold was discovered in 1848, and by 1849 the rush was on. Now, rather than a few hundred wagons a year, there were thousands. Pioneer diarists reported an uninterrupted line of wagons stretching 1,000 miles across the prairie. In 1849, 21,000 forty-niners made the journey, crossing the Sierra in fairly equal portions between the Lassen Route to the north, the Carson River Route to the south, and the Truckee River Route. Most emigrants on the Truckee took their wagons up Cold Stream Canyon.

The quest for gold and the mass migration continued through the early 1850s. Up to 50,000 people made the overland journey each year from 1850 to 1852. Most chose the Carson River Route 50 miles to the south, avoiding the dozen or so hazardous crossings of the Truckee River and the brutal granite wall that stood between them and their fortunes.

The PCT descends 1,150 feet over the next 1.5 miles into the American River Canyon. After a mile of steep switchbacks, the descent becomes more gradual. You drop to 7,600 feet and cross a 4-foot-wide creek that flows out of Meadow Lake. It joins other small streams to form the American River and carve its magnificent canyon.

The trail climbs, passing Painted Rock Trail at 9.3 miles. After another 1.2 miles and an ascent of 560 feet through dense forests, you reach the junction with Granite Chief Trail at 10.5 miles. Turn left on the Granite Chief Trail, and continue another 2.9 miles to Squaw Valley, a descent of 1,900 feet.

The trail alternates between pleasant switchbacks and scrambles over granite shelves. Giant ponderosa and Jeffrey pines now appear as you lose elevation. Ancient, gnarled western juniper with reddish bark and blueberry-like cones grow in impossible rock crevasses, seeming to have chosen the most difficult spot to live for a millennium or perhaps three. Approaching the valley floor, we were greeted by stands of aspen dressed in their brightest golden-yellow autumn colors.

The trail reaches Squaw Creek and diffuses into several small trails that end at the valley’s north parking lot near the Olympic Village Inn. After 8.5 hours on the trail, we checked into PlumpJack’s. It was the slowest season of the year. With the Jacuzzi to ourselves, we soaked our weary muscles under the towering mountain peaks and star-filled sky. Then we headed off to Suko Yama’s for a sushi feast.

Day 2: Squaw Valley to Truckee River at Alpine Meadows Road

DAY 2 STARTS BY RETRACING YOUR STEPS up the Granite Chief Trail, the steepest sustained ascent of the walkabout with a 1,900-foot climb over 2.9 miles. You may want to skip this section and shorten the hike by taking the aerial tram to Squaw Valley Resort’s High Camp. It costs $46 and usually runs in summer and during ski season. Follow The Route, to return to the PCT. For tram information, call 800-403-0206 or go to squawalpine.com.

The cable car was not running in October, so we headed back up the Granite Chief Trail. Finding the trailhead out of Squaw Valley can be confusing because it fans out into several minitrails as it approaches the valley. Consult The Route for detailed directions.

You can take the aerial tram from Squaw Valley to Squaw’s High Camp.

The trail climbs steadily through gradual switchbacks past sturdy junipers and stately Jeffrey and ponderosa pines. It scrambles over granite shelves with views of Squaw Valley and the surrounding peaks. As we methodically climbed, four young women ran past us. “Where are you headed?” we asked. “Donner Pass,” they cheerfully replied.

We watched them quickly disappear into the fir and pine forest of the higher elevations on their 13.4-mile jog. Scott said, “Ours might be the last bootprints of the season, but it looks like there will also be four sets of running shoes.”

It took us 2 hours to climb the 2.9 miles back to the PCT. Turn left, head south, and continue a gradual ascent toward Granite Chief. You pass a marshy meadow, the headwaters of Squaw Creek, and then climb a short series of switchbacks. After passing under a chairlift, you reach the junction of the Western States Trail in a saddle between the back of Squaw Peak and Granite Chief.

To our astonishment, three young men came running up the trail. They asked, “Which way to Donner Pass?” Members of a Nordic ski team from Vermont, they had come to the Sierra to train. They hoped to catch up to the four women, who were their teammates. Nothing like a brisk 20-mile jog in the mountains to get the heart pumping. We pointed them in the right direction, and they waved and pranced off like gazelles. Scott said, “Make that seven sets of running-shoe tracks in the snow covering our bootprints.”

The PCT descends right. A hundred yards down from the junction is a sign marked GRANITE CHIEF WILDERNESS, 4.2 miles from the trailhead. Here a Steller’s jay taunted us from the branch of a mountain hemlock, and two chipmunks busily gnawed on pinecones, fattening up for the long winter.

The Western States Trail follows the PCT 0.2 mile and then breaks off to the west. After another 0.8 mile you come to the northwest-heading Tevis Cup Trail, the route of the annual Tevis Cup Ride, a 100-mile, one-day horse race from Tahoe to Auburn. Between the two trails, you cross a small stream, the headwaters of the North Fork of the mighty American River.

The PCT descends through a series of switchbacks, dropping into the Whiskey Creek watershed. You reach Whiskey Creek Trail at 7 miles after dropping 1,330 feet from the Western States Trail junction. Now the PCT climbs gradually northeast 0.9 mile to the Five Lakes Trail.

Turning onto Five Lakes Trail, you leave the PCT after hiking it for the better part of two days through some of the most spectacular scenery in the Sierra. A taste of the PCT leaves the hiker yearning to come back next season to explore it again; you might consider the two other walkabouts in this book that visit the PCT (see “Crossing the Sierra on the Emigrant Trail,” and “Exploring Lassen Volcanic National Park,”).

The trail climbs gradually 0.3 mile, crossing Five Lakes Creek. It levels off as you enter Five Lakes Basin. Easy access and crystal-clear alpine lakes surrounded by granite walls and fir forests make this a popular destination in the summer. A side trail branches off to the lakes 0.9 mile from the PCT junction.

The small lakes had been warming up all summer, but apparently a few subfreezing autumn nights were enough to cool them back down. Drying in the sun on a warm granite ledge after a brief and energizing swim, I thought of the words of George R. Stewart, writing about the pioneers in his book, The California Trail:

The psychology would have been that of the traveler—and there is no more pleasant state of mind for most people. When anyone is traveling, life is reduced to a simple and solvable daily problem: to make the required distance. If the people in a wagon train totaled their fifteen miles westward, they could sleep peacefully.

The psychology is just as true for today’s inn-to-inn hiker. The hectic demands of modern life melt away, and you are left with the joy of a deep encounter with nature. Your only “daily problem” is to make the required distance to your next inn and then to enjoy the pleasures of dining by a roaring fireplace and sleeping under a down comforter.

Five Lakes Trail descends steadily, dropping 1,000 feet over 1.4 miles to Alpine Meadows at 6,560 feet. As you lose elevation, the Alpine Meadows Ski Resort comes into view. Giant Jeffrey pines and then aspens appear as you reach the valley at 10.2 miles. The trail ends at Alpine Meadows Road. The ski resort is to your right, but it is closed in the summer.

Take the Bear Creek Trail downvalley 1.9 miles. Finding the trail is a bit tricky; see The Route, for directions. This lovely trail passes through dense pine and fir forests along the south side of the canyon. Countless springs, seeps, and creeks flow across the trail and into Bear Creek as it races to the Truckee.

The trail drops back down to Alpine Meadows Road. Turn right, and walk the broad shoulder of the road 0.5 mile until you reach the Truckee River and River Ranch Lodge.

The lodge sits on the river’s edge. The rooms are small and comfortable, and the Truckee flowed below our balcony. We dined on portobello napoleon and a delicious rack of lamb with a mustard-rosemary glaze. The river takes a turn and forms a large pool below the lodge’s deck. Kayakers and inner tubers gather here in the summer after floating down from Lake Tahoe. There is live music and an outdoor bar on the deck on summer weekends.

The Pacific Crest Trail in late autumn

Truckee River

Day 3: Alpine Meadows Road to Lake Tahoe

THE LAST LEG OF THE JOURNEY is a brief 4-mile stroll on the hiker/biker path along the river to Lake Tahoe, a gradual reintroduction to civilization. A noisy flock of Canada geese honked loudly as they flew up the valley and landed in a deep pool. We lingered, not wanting to rush, savoring the beauty of the Truckee and then the grandeur of Lake Tahoe. This 30-mile walkabout is a stroll through pioneer and geological history and a hike through the spectacular beauty of the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

THE ROUTE

All mileages listed for a given day are cumulative.

Day 1: Donner Pass to Squaw Valley

See Transportation for driving directions to the trailhead. The PCT starts to the left of the trailhead sign. You will stay on the PCT, heading south, for the next 10.5 miles

Hike the PCT to the Mount Judah Trail. 2.1 miles

Continue to Anderson Peak Trail. At an unmarked fork in the trail, turn right. The PCT circles the west side of Anderson Peak. 5.1 miles

Continue to Cold Stream Trail. 7.8 miles

Continue on the PCT to Painted Rock Trail. 9.3 miles

Continue to the junction of Granite Chief Trail, and turn left. 10.5 miles

The Granite Chief Trail splits into several branches as you approach Squaw Valley, but all the branches lead to the parking lot adjacent to the Olympic Village Lodge in Squaw Valley.

total miles 13.4

Alternate Route for End of Day 1

You can take the Squaw Valley Aerial Tramway to the valley and avoid 1,200 feet of descent on Granite Chief Trail. Continue south on the PCT past the Granite Chief junction 2.3 miles to Tevis Cup Trail, and turn left. Follow the Tevis Cup Trail 0.3 mile. The trail then angles south up to the ridgeline. A stone monument commemorating the Emigrant Road stands where the trail crosses the ridge. Descend on gravel roads past the Gold Coast Express ski lift, turning left at the T junction, and descend past the Shirley Lake and Big Blue ski lifts. Stay left at the Y intersection, and hike into Squaw’s High Camp. Take the aerial tram to the valley. The last tram leaves at 5 p.m. It may be closed between Labor Day and the opening of ski season. For more information, go to squawalpine.com or call 800-403-0206.

Day 2: Squaw Valley to Truckee River at Alpine Meadows Road

You may want to take the Squaw Valley Aerial Tramway from Squaw Valley to Squaw’s High Camp ($46 for an all-day pass). For information, go to squawalpine.com or call 800-403-0206. Pick up a Squaw Valley Hiking Guide when you purchase the pass. Hike Ridge Road out of High Camp. Take Siberia Ridge Road past the Big Blue and Shirley Lake ski lifts. Turn right on Emigrant Peak Road at the Gold Coast Express ski lift, and hike to the ridge and a stone monument commemorating the Emigrant Road. Descend to a junction. Take Tevis Cup Trail left 0.3 mile to the PCT, and turn left.

The Granite Chief Trailhead is found at the northwest end of Squaw Valley’s north parking lot. Cross a small bridge to the right of the Olympic Village Lodge, and walk up 100 feet. Turn left on unmarked Granite Chief Trail, which runs through the ropes course. Follow the trail along Squaw Creek. Shirley Canyon Trail continues along the creek. Granite Chief Trail turns right and starts climbing. Continue to the junction of the PCT. 2.9 miles

Turn left and hike south on the PCT 5 miles. The trail reaches a saddle between Squaw Peak and Granite Chief Trail and an unnamed trail. Take the right fork. The sign marking the boundary of the Granite Chief Wilderness is 100 yards beyond the fork. 4.2 miles

Continue to Whiskey Creek Trail. 7.0 miles

Reach the junction of Five Lakes Trail, and turn left, leaving the PCT. 7.9 miles

Follow Five Lakes Trail to Alpine Meadows Road. 10.2 miles

Cross Alpine Meadows Road, and walk right 100 yards. Take the unmarked, unpaved road to the left, the start of the Bear Creek Trail. After 50 feet take the unmarked trail to the left, descending three stone steps, and hike toward the sound of rushing water to a bridge over Bear Creek. The trail climbs a series of switchbacks to a paved road. Make a short jog right, cross the road, and find the trail, marked by two metal posts. The trail briefly turns southwest, the opposite of the way you want to go, but don’t despair—it climbs, turning back northeast. The trail briefly joins a rocky road. After a short distance the road crests, and you will see a large green water tank. The trail turns off to the right, marked with a metal diamond nailed to a post. After a short distance, you will reach a junction marked with a metal post. Take the trail to the left. Ascend a small hillock, and angle to the right on the narrow trail. Continue straight, crossing a dirt road. The trail is marked by a post with a diamond. Continue on Bear Creek Trail along the south slope above Bear Creek Valley until it descends back to Alpine Meadows Road. 12.1 miles

Turn right on Alpine Meadows Road, and walk along the shoulder to the Truckee River and the River Ranch Lodge.

total miles 12.6

Day 3: Alpine Meadows Road to Lake Tahoe

Walk to Lake Tahoe and Tahoe City on the Truckee River hiker/biker trail.

total miles 4.0

TRANSPORTATION

Driving with Two Cars

LEAVE ONE CAR IN TAHOE CITY, and drive the other to the Donner Summit and Pacific Crest Trailhead. Take the Soda Springs and Norden exit off I-80 and drive east on the old Donner Pass Road 3.6 miles. Turn right on the road across from the Donner Ski Ranch; a sign at the intersection reads SUGAR BOWL SINCE 1939—MT. JUDAH PARKING. After 0.1 mile, take the first left and go another 0.2 mile to a small parking area on the left. The trail starts 100 feet beyond the parking area on the right. If the parking area is full, return to Donner Pass Road, and park in a turnout.

Driving with One Car

DRIVE TO THE DONNER SUMMIT and Pacific Crest Trailhead. Follow the directions above. To return to your car, Tahoe Area Regional Transit (TART) buses run from Tahoe City to Truckee regularly during daylight hours; go to placer.ca.gov/departments/works/transit/tart.aspx. There are several taxi companies serving the Truckee area. Try High Sierra Taxi (530-412-1927). The ride back to the trailhead and your car should cost $20–$30.

Headwaters of the mighty American River

By Train

TAKE A BEAUTIFUL AND RELAXING train trip from the Bay Area, Sacramento, Los Angeles, or Reno to Truckee on Amtrak (amtrak.com). The trip from the Bay Area to Truckee costs $49–$53 and should take anywhere from 5 to 6 hours. See Driving with One Car, previous page, for information on taxis from Truckee to the trailhead to start the hike and on public transportation from Tahoe City back to Truckee at the trip’s end.

Flying into the Bay Area

FOR TRIP PLANNING from the airport to Amtrak, visit 511.org. From SFO take BART to the Oakland Coliseum Station ($9.70), and walk a few minutes to the Amtrak Station. From the Oakland International Airport take the AirBART Shuttle to Oakland Coliseum BART Station ($6), and walk a few minutes to the Amtrak Station. Take an Amtrak train to Truckee, and follow the By Train directions (above).

MAPS

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC’S Lake Tahoe Basin (#803) is a great recreational topo map that covers this entire route. It can be purchased for $11.95 at shop.nationalgeographic.com.

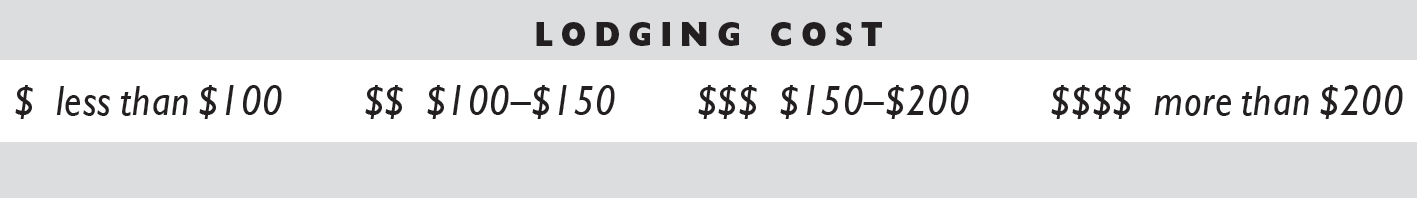

PLACES TO STAY

Squaw Valley

PLUMPJACK SQUAW VALLEY INN $$$$ • 1920 Squaw Valley Road • 530-583-1576 • plumpjacksquawvalleyinn.com • Full breakfast included.

OLYMPIC VILLAGE INN AT SQUAW VALLEY $$$$ • 1909 Chamonix Place • 800-989-1387 • 530-581-6000 • olympicvillageinn.com

THE VILLAGE AT SQUAW VALLEY $$$$ • 1750 Village East Road • 530-583-4264 • squawalpine.com • Vacation rental condominiums.

Snow-dusted peaks along the Pacific Crest Trail

Alpine Meadows

RIVER RANCH LODGE $$–$$$$ • At CA 89 and Alpine Meadows Road • 4 miles north of Lake Tahoe • 530-583-4264 • riverranchlodge.com

Truckee

TRUCKEE HOTEL $–$$$$ • 10007 Bridge St. • 530-587-4444 • truckeehotel.com

RIVER STREET INN $$–$$$ • 10009 E. River St. • 530-550-9290 • riverstreetinntruckee.com • Continental breakfast included.

CEDAR HOUSE SPORT HOTEL OF TRUCKEE $$$–$$$$ • 10918 Brockway Road • 530-582-5655 • cedarhousesporthotel.com

Tahoe City

MOTHER NATURE’S INN $–$$ • 551 N. Lake Blvd. • 530-581-4278 • 800-558-4278 • mothernaturesinn.com

AMERICA’S BEST VALUE INN $$ • 455 N. Lake Blvd. • 530-583-3766 • 866-588-8247 • redlion.com/tahoe-city • Continental breakfast included.

BASECAMP HOTEL $$ – $$$ • 955 N. Lake Blvd. • 530-580-8430 • basecamptahoecity.com • Continental breakfast included.