Location: Bridge Street, Brickmaker’s Kloof, Port Elizabeth Web: bridgestreet.co.za Tel: 041 581 0361 Amenities: Restaurant, beer tasting, coffee shop

People have been waiting years for the Bridge Street Brewery to open. They might not have realised they were waiting for it to open, but they were, for the brewer at the helm of this stylish brewpub is a man who could be called the godfather of South African craft brewing – Lex Mitchell. The founder of the country’s first microbrewery, Mitchell’s in Knysna (see page 87), has been conspicuously absent from the brewing scene for too long and his return seems like a sign that craft brewing has finally come of age in South Africa. And it seems no one has been waiting for Bridge Street to open more than Lex himself. Since selling Mitchell’s in 1998, Lex looked at starting breweries in some unlikely locations – the remote islands of Mayotte and St Helena among them. Then, after several setbacks, an opportunity arose a little closer to home – in fact, in the very city he calls home: Port Elizabeth.

“I was quietly sitting at home looking at other ventures when I was approached by Gary [Erasmus – the landlord of the building and a partner in the brewery] in April 2011,” Lex explains. “My involvement was simple – he asked if I’d be interested and I said yes!” Lex had already been brewing up some business plans of his own and while his vision to open an English-style pub didn’t transpire, some of the ideas live on in the names of the beers. The restaurant side of things – something Lex admits he didn’t know anything about – was left to Donovan Noyle, a familiar face on the Port Elizabeth food and beverage scene. The brewing was left to Lex. “I had an idea of what I wanted to brew,” he says and had been practising his recipes on an adorable wood-panelled homebrew system over the years. Bridge Street’s trio of beers are reminiscent of the long-established Mitchell’s brands in that they’re not overly fizzy and are faultless in every way, but the styles are all new, as are their names. “The names of our beers perhaps have an unusual provenance,” Lex explains. “I had the idea to start a medieval village, an idea that stemmed from the medieval fair that I’ve put on in PE for the past 11 years. That never came to pass but I had a page full of beer names, and that’s where these came from.” While the pub is named for the street on which it sits, the brewery’s moniker – Boar’s Head – is taken from the Mitchell’s family crest and the beer names from Lex’s passion for all things medieval.

BOAR’S HEAD BEST BITTER (4.5% ABV)

Modelled on the British beer that first inspired Lex to launch a microbrewery, this is an understated ale with only the vaguest of aromas. Malt and hops are in perfect balance, giving a beer that has hints of fruit and bitterness in equal doses.

CELTIC CROSS PREMIUM PILSNER (5% ABV)

Light fruit on the nose and with a pleasant but subtle sweetness, Bridge Street’s most popular brew is dangerously easy to drink and infinitely moreish.

BLACK DRAGON DOUBLE CHOCOLATE STOUT (4% ABV)

A medium-bodied stout that is rich in coffee and dark chocolate both on the nose and the palate. There’s a luscious, long finish with lingering flavours of espresso.

Between talk of Lex’s hobby of “Robin Hooding”, which he describes as “shooting foam animals with a longbow”, and of the research he’s done into the family name, it is evident that he still also has an immense passion for brewing.

For the first few months of Bridge Street’s existence, Lex was rising at 5 a.m. and brewing up to five times a day on the 50-litre system he’d brought from home while the 300-litre system was waiting to be installed. The pressing need for a larger brewery was also the reason that a changeover was proving difficult – the huge and constant demand for beer, especially the flagship Celtic Pilsner, meant Lex was frantically stockpiling enough to get him through the days when the new system would be set up and tested. Luckily though, and rather unusually for a brewpub, Bridge Street stocks a wide range of South African craft beers – something that helps out when demand gets to be too much. Alas, you’re unlikely to ever find Lex’s beers on tap anywhere else – he’s adamant that they’ll only ever supply Bridge Street. This is in no small part because the constant brewing takes up so many hours, there is no time left to experiment. “I do feel that the creative side has been stifled because of the hours that I’ve had to put in. I have done some unusual brews at home that I would like to do again,” he says, but is tight-lipped on what those future brews might be. There are firm plans to add a cider to the range, a perfect pint for sipping on the terrace overlooking the Baaken River.

Bridge Street manages to marry classic beers and modern décor, creating an instantly popular hang-out – one which launched quietly and gained popularity without any real marketing. The building started out as a fibreglass factory and Donovan laughs when he thinks back to the day he first saw it. “Two years ago if you’d looked at this building people would have said you’re absolutely mad – it was totally derelict,” he says. But the revamping of the building has led to a rejuvenation of the valley, making the area a popular spot for weekend family outings as well as boozy midweek nights out. “The public response has more than exceeded our expectations,” says Donovan, “and they were high to begin with.”

Lex is coy when it comes to acknowledging his position as founder of craft beer in South Africa, but he will admit that he finds the recent beer boom exciting. “I loved the idea in Britain that you could go to a village and each place would have its own brewery. I don’t think it’s spread far enough in South Africa yet, but it seems that it’s finally getting there.”

Donovan sums up the boom perfectly with his final words before rushing back to the heaving restaurant. “Craft beer has become the best thing since wine,” he says. I couldn’t have put it better myself.

Should all beer be served ice cold or should different beers be served at different temperatures?

“My firm conviction is that to get the best out of a beer it should be served at a temperature which is not so cold as to ‘lock’ in the aromas waiting to be released and which contribute immeasurably to the enjoyment of a well-crafted beer. Ales and stouts have a real smorgasbord of nasal and palate exciters which are lost when poured too cold. By the same token, however, on a really hot day, an ice-cold beer goes down wonderfully well and when one is thirsty, this is about all that is necessary.”

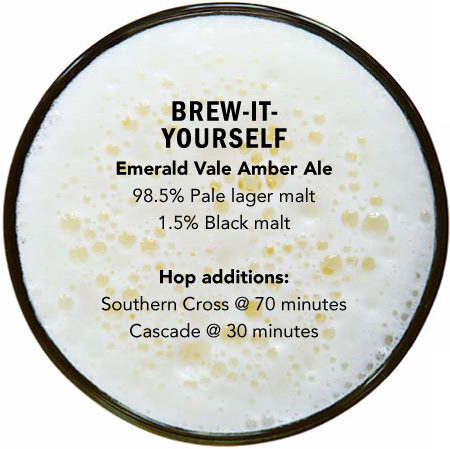

Location: Emerald Vale Farm, Off Cintsa East Road, Cintsa Web: emeraldvalebrewery.co.za Tel: 078 614 0150 Amenities: Tours by appointment, off-sales available after tours or by appointment

Chris Heaton’s dreams of launching South Africa’s first “estate brewery” might have hit some huge hurdles early on, but his beer has been met with such gusto in its Wild Coast home that he just can’t keep up with demand and for the moment at least has put his barley field on the back burner.

It was never going to be an easy feat – estate breweries, ones where all the barley and hops are grown on site, are as scarce worldwide as breweries in any form are along the Wild Coast, though Chris certainly gave it a brave shot. “At one stage I even wanted to build my own malting plant though I think the project was a bit ambitious!” Chris laughs, shaking his head. “But I grew the barley and got to know the ingredients, which was a great exercise. And I did learn how to plough!” Chris’s attempts at growing hops have been a little more successful, with his first vines producing cones after just three months. “I’d like to use 100% of my own hops for the bittering hops,” says Chris, though if local demand keeps up, he’ll have to look at adding a few more hop vines to his land.

It’s a project that deserves to pay off. Chris is a humble guy with a hankering to learn everything about his newly chosen craft. The idea started in 2010 when Chris started making kit beers. Once he moved to all-grain brewing, Chris began to toy with the idea of opening a brewery on his family farm, just outside Cintsa. “I wanted to do something on the farm that’s related to tourism,” Chris explains. “There’s a lot of potential in this area but it’s very under-advertised. It’s growing though and I’d like to be a part of it.” With the land available and a background in the construction industry, Chris had the perfect launch pad and set about investigating the industry – and the competition.

Chris Heaton is one of few brewers who grows his own hops.

“I went around to a lot of different breweries in South Africa and did a 10-day stint working at The Little Brewery on the River [see page 139] as well as the Misty Meadows weekend brewing experience [see page 83],” says Chris. “One of the breweries I visited was Mitchell’s. I looked at their system and realised that I should keep to the basics.”

The equipment might be rudimentary, but the beers are superb.

Chris’s system is indeed in keeping with the surrounds in its rusticity, but he has proved that good beer is as much about the brewer as the equipment. There’s no doubt that his humility and self-criticism have served him well along the way. “I don’t know everything about it,” he admits. “I feel like I’ll need at least 10 years’ experience to call myself anything like a brewmaster!” Of the first seven brews, Chris ditched two, though he has no regrets about the failed batches. “I love tasting different kinds of beer, but I also love tasting things that are wrong with beer and identifying what went wrong in the process” – a philosophy that promises to take him a long way on the craft beer scene.

Solar-powered Emerald Vale – named for the farm it sits on – is one of the country’s newest breweries, established in April 2012. Once Chris can keep up with demand from local restaurants and the thirsty backpackers that flock to the Wild Coast, he plans to start tours of his brewery as well as a couple of restaurants in the region. In the meantime you can count on a range of beers made only with rainwater and featuring some measure of home-grown hops. And will there be any Wild Coast malt featuring in Emerald Vale’s beers in the near future? “Unlikely,” laughs Chris. “But I do think the barley adds a certain ambience to the brewery!”

Why does my beer smell like a tin of sweet corn?

“The cause of this off-aroma is dimethyl sulphide (DMS). If you smell this in your beer, somewhere in the chain there is something that has not been done correctly. It could be from using poor malt, or from certain brewing procedures. Ensuring a good 70–90-minute boil with the lid off the boiler and then making sure that the wort is cooled quickly should ensure that the cause of this kind of smell is eradicated. Remember that DMS is acceptable – in small amounts – in lagers.”

GOLD ALE (5.6% ABV)

This pale gold-coloured ale is mild on aroma but if you sniff deeply enough you’ll find evidence of malt. It’s a very well-executed entry-level ale with a perfect balance of bitter and sweet flavours and a pleasing finish that leaves you wanting more. A great first leap for lager lovers.

AMBER ALE (5.6% ABV)

A little darker in colour, this highly drinkable ale also offers a hint of sweetness on the nose. There’s a hint of roasted malt when you sip and a touch more bitterness than the Gold Ale delivers.

Also look out for Emerald Vale’s Pale Ale, a slightly hoppier beer.

1.75 litres chicken stock

15 ml olive oil

150 g streaky bacon, diced (keep one rasher for garnishing)

1 large onion, diced

2 large sticks celery, sliced and diced (keep leaves for garnish)

15 ml finely minced garlic

500 ml Arborio rice

200 ml of a hop-forward beer, such as Emerald Vale’s Amber Ale

50 g butter

60 ml grated Parmesan cheese

Salt and pepper

SERVES 4–6

Location: 20 Wharf Street, Port Alfred Web: littlebrewery.co.za Tel: 046 624 5705 Amenities: Restaurant, tasting room, brewery tours, shop, off-sales

The eminently affable Ian Cook doesn’t mind admitting that he “bumbled into the whole brewery thing”, though it might seem more like fate guided him to take over Port Alfred’s long-standing but somewhat beleaguered brewery. After a brief but successful search for a semi-retirement business in small-town South Africa, Ian moved from Johannesburg to the Eastern Cape coast.

“I was initially interested in the Pig and Whistle, South Africa’s oldest pub,” Ian explains. “I was trying to work out how to make money and I thought we could stick a brewery in it!” With the new idea in mind, Ian started scouting around for secondhand brewing equipment and found out about the vacant brewery in Port Alfred. Although established in 1998 as the somewhat successful Coelacanth Brewery, the setup had changed hands several times and hadn’t been functioning for six years when Ian clapped eyes on it. “In my naivety I honestly believed I could reverse up in a bakkie, take out two spanners and move all this kit to Bathurst,” laughs Ian. A weekend at the brewery followed, which is when Ian fell in love and all the plans changed. The love in question was the mid-nineteenth century building housing the brewery. “I could really see us doing things with it,” says Ian, “and by the end of the weekend I called the owner and said I don’t want the equipment – I want the whole shooting match!”

The Kowie Gold Pilsner is The Little Brewery’s flagship beer.

Thanks to Ian, the building had finally found its goal in life. After a sombre start as the harbour-master’s offices and warehouse during Port Alfred’s heyday years during the Frontier Wars, it tried a spell as the town hall, but deep down it always knew it was destined for a career in entertainment. After stints as a bottle store, cinema, restaurant and nightclub, it finally decided it wanted to be a brewery when it grew up, but it took a few brewers to help the old building achieve its potential. “It’s a nice old girl!” says Ian, looking around at the high ceilings and thick stone walls, clearly glad that he opted to stick around when first spent a weekend here in 2008. That weekend was fateful in more than one way. Not only did Ian find a home for his new business, he also found a brewer. Thanks to a tip-off from the SAB brewer who had given the OK to the brewing equipment, Ian tracked down Colin Coetzee, a retired SAB brewer living in nearby Kenton-on-Sea, and The Little Brewery on the River began its first brew in 2009. Colin says his foray into brewing was simple – he flunked university and applied! But it was obviously the right path since he stayed with SAB for a further 34 years, working at breweries throughout Africa. You can quickly tell that Ian and Colin enjoy a friendship rare to people who have only known each other a few years. “I haven’t played one game of golf since I started here,” Colin mock-complains, referring to his retirement being cut short by Ian’s venture. But it seemed that Colin was just waiting for someone to urge him back to the brewing scene. “I didn’t take much convincing,” Colin confesses. “I got on an ego trip – I wanted to know that I could still do it.” “Just as well,” adds Ian. “Because we couldn’t do it without him.”

KOWIE GOLD (4.5% ABV)

This crisp, clean pilsner is crystal clear and the colour of pale straw. Although mildly fruity on the nose, it has a dry, refreshing finish – a definite session beer.

SQUIRES PORTER (6.5% ABV)

Mild coffee aromas give way to a roasty pint that is dangerously drinkable considering its alcohol content. It is lighter in body than your average porter.

Also look out for the copper-coloured Coin Ale.

Bethwell (left) and Alert are probably South Africa’s only teetotal brewers.

The camaraderie of the team is a delight to behold, and it’s not just Ian and Colin who are having a ball at the brewery. The two assistant brewers, brothers from Zimbabwe, are also filled with an enthusiasm that bubbles over into the beers they brew. Bethwell Dube had been working as Ian’s gardener for years when Ian made the move from Joburg to the Eastern Cape and it didn’t take long for him to decide to also opt for a new home and a new career. The move involved a lot of firsts for Bethwell – his first plane ride (“I was a bit shaky”), his first sight of the ocean (“amazing”) and, of course, his first time in a brewery (“a great challenge!”). His brother, Alert, followed two years later and gives off the aura of a man who has been brewing his entire life. “Colin taught us nicely,” he says modestly, but Colin and Ian both acknowledge that Bethwell and Alert were perfect students. “One of the biggest satisfactions I have is seeing Bethwell running the brew house,” says Colin. “I made a man out of him!” Bethwell and Alert often take care of the brewing if Colin is not around and their eyes light up as they talk about their new profession with a rare and enviable passion – no mean feat for two people who neither drink nor even taste the beers they produce.

Colin and Ian have been known to partake of the occasional pint though and the two devised the recipes for the three beers along with a little help from the SAB plant in Port Elizabeth. The range began with a crisp and clear pilsner, following a year later with an ale, then a porter another year after that. Their beers use local ingredients, save for the Saaz hop featured in the pilsner. “We have a water problem in Port Alfred,” admits Colin, “but I don’t.” He refers to the sub-par tap water in the town and the rainwater collected on the brewery roof, the only water used in the trio of beers.

Since opening, the brewery has witnessed the kind of success it had been waiting for since it was first installed. The beers are found on tap throughout the town, as well as in neighbouring Kenton, Bathurst and in a few select spots in Grahamstown. For takeaways, you’ll have to visit the brewery shop, which also stocks glasses and a range of light-hearted beer T-shirts that epitomise the cheery, amiable nature of this coastal brewpub.

What is “lacing”?

“Lacing” is the foam that is left over after you have taken a drink of beer. In general, the foamier the beer, the more lacing left over after drinking (beer is foamier, or the foam is denser, when it has smaller bubbles, as opposed to large ones). The foam is generally a function of the beer’s ingredients. The proteins in the beer link together, becoming sticky, and cling onto the side of the beer glass. This foam also helps to keep the carbon dioxide in the beer, thus keeping it bubbly and creamy while it is being drunk. The higher the protein level, the denser the foam, as the CO2 has more to adhere to. For comparison, carbonated soft drinks are low in protein, and thus have little foam. Lacing is always more evident when a clean beer glass is used; a dirty or oily glass results in less foam and lacing.”

Pair with a pilsner, such as The Little Brewery’s Kowie Gold. Pilsner is a clean, delicate beer that pairs well with an array of dishes. Consider it a palate-cleanser here, allowing you to savour the more delicate flavours of the fish.

300 g flour

Salt (to taste)

3 eggs, beaten

500 ml Kowie Gold Pilsner (or other pilsner)

250 ml water

6 hake fillets

Oil for frying

SERVES 6

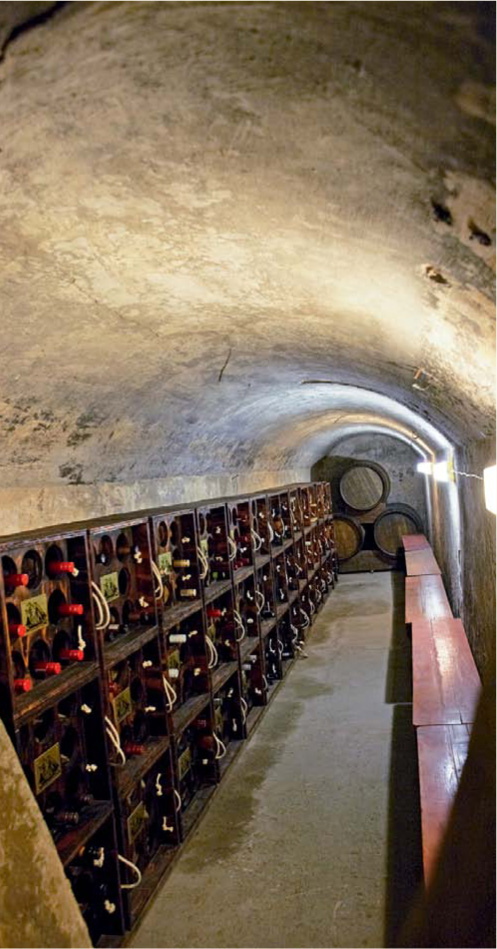

The one-time reservoir now serves as the Wharf Street Brewpub’s wine cellar.

Location: Old Power Station, Reynolds Street, Highlands Industrial Area, Grahamstown Web: iqhilika.co.za Tel: 046 636 1227 Amenities: Off-sales, tastings by appointment

People get into booze production for all manner of reasons, but none is quite so cryptic and bizarre as the reason Dr Garth Cambray gives for his induction into the world of mead-making: “somebody stole my bicycle.”

To elaborate, on the day his bike was taken, Garth bumped into a university friend he might not have otherwise seen. The friend was off to India and mentioned he was giving up his job working with a professor at Rhodes University. The job in question involved honeybee research, so Garth filled the vacancy left by his student pal and from there an interest in bees developed. “As soon as I started keeping bees, my parents’ gardener began pinching honey to make iQhilika. It was him who explained iQhilika to me,” recalls Garth. iQhilika is the Xhosa word for mead and has been made in South Africa for millennia. The encounter with his parents’ gardener would launch a lifelong passion for mead that stretches far beyond a passing interest.

“In my third year I did a microbiology project on iQhilika,” says Garth, in which he learned to make it and started looking at the yeast in greater detail. From there an honours degree and PhD on the subject followed, the latter looking both at inventing new brewing technology for this ancient beverage and also at how making mead might benefit the local community. “One of the problems with university research in South Africa is that it doesn’t actually create jobs to economically empower local, rural communities,” Garth explains. “We’re very proud to say that this does.”

The research paid off in every way. Not only did Garth invent a revolutionary way to make mead that is as baffling as it is brilliant, he also succeeded in creating jobs within the local community. Sindiswa Teyise, Director of Operations at Makana, heads up the beekeeper training project and has trained close to 500 beekeepers in the Transkei area. She came to Makana to work as a receptionist, but her oft-quoted mantra of “I can do that” now sees her training beekeepers, keeping accounts and taking care of the mead-making process.

Dr Cambray’s mead-making invention (seen here on the right) looks simple, but the processes happening within are baffling.

The process is simple, though the science behind it is not – honey and water are first blended together and heated to 75 °C in a process that takes about 3 minutes. From here, Garth’s invention enters the proceedings. It is a basic-looking contraption, a narrow pipe reaching from floor to ceiling in the atmospheric old building – a disused power station on the outskirts of Grahamstown. It takes a mere 90 minutes for the honey and water solution to be pumped up the pipe, en route passing through a yeast colony that has been designed to speed up the fermentation process.

Dr Garth explains the process, which is mystifying in its simplicity: “At the bottom there’s a whole lot of yeast that is adapted for a high sugar, low alcohol environment; in the middle you’ve got the yeast that are adapted for moderate sugar, moderate alcohol and at the top you’ve got yeast that are adapted for low sugar, high alcohol.” He likens the process to a car manufacturer’s assembly line, where each worker has a set job to do. “It’s essentially a colony of yeast with a number of different skills.” Remarkably, the yeast used was inoculated in 2000 and hasn’t needed changing since. “We have not opened or taken out the yeast since 2001 on the main fermenter, but it is derived from an earlier culture developed in 1998–2000,” Garth explains, calling his colony “an immortal consortium of yeast”. To put this into perspective, a lot of breweries use new yeast for every brew, while others generally limit their re-use to five or six brews.

Once the honey and water solution reaches the top of the pipe, it is fully fermented into a tangy, sweet, wine-like beverage with an alcohol content of 12% ABV. It’s another remarkable process and one that’s difficult to get your head around after spending time in breweries, where fermentation generally takes between three and ten days. Fermentation strips away much of the honey’s sweetness and some of the flavour so each batch is re-sweetened with another honey dose. Makana can make 300 litres of mead over the course of one working day and, theoretically, it could be bottled the same day. Generally though, Garth likes to let it sit in oak barrels for a few months before exporting it, as he does with the majority of his mead, to the USA. However, plans are afoot to distribute more widely in South Africa. “We’re finding that with the microbrewery boom we’re getting a lot more interest in the product here,” says Garth. It would be a pattern that mimics that of the States, who began with a craft beer revolution and followed it up with ever-deepening interest in cider and mead.

The finished product is perhaps an acquired taste, though Makana’s range of meads means there should be something for all palates. Plus, as it keeps for up to four months after opening (assuming it’s refrigerated) you should have time to develop a taste for this ancient and yet rare beverage. Garth tells of mead’s antioxidant properties and insists the beverage gives little hangover – perhaps a theory to test out once you’ve visited this extraordinary establishment in the Eastern Cape.

It is mentioned in legend and lore, referred to in classical literature and is widely acknowledged as the world’s oldest way to get drunk, but for all of mead’s distinctions it is still one of the most humble boozy beverages there is.

Although many mead makers add various herbs or flavourings to give their versions character, at heart the drink has only three ingredients – water, honey and yeast. In fact, the advent of mead actually predates the man-made stuff, created by chance when beehives received the brunt of a deluge and the wild yeasts within the honey began to ferment.

Mead is often associated with medieval wenches and European kings, though its story dates just as far back in Africa as it does in Europe. In fact, the Khoisan were making what they called !karri long before Chaucer had worked out which end of a quill to use. They doubtless stumbled across it by accident, but quickly took a liking to its seemingly magical powers. Indeed mead, like honey, has long been linked to the gods, be they Roman, Greek or Druid, and is thought by many to be the oft-quoted “nectar of the Gods”.

Today mead is making a resurgence in some parts of the globe, often hot on the heels of a craft beer boom. Mead is not beer; its production is less complex than brewing and the end product more similar to wine, at least in alcohol strength and appearance. But mead is an integral part of South Africa’s millennia-old love affair with a good tipple and a beverage that is likely to gain popularity in the not-so-distant future. Its aromas and flavours are both complex and subtle, owing to the vast number of varied flowers each bee involved in the honey-making process has visited.

Mead can be sparkling but is usually still and is best served chilled in a red-wine glass. Enjoy sweeter versions with spicy food or strong cheese, while dry styles pair well with fish, chicken and seafood dishes.

AFRICAN TRANSKEI GOLD COFFEE (12% ABV)

With aromas of Grandma’s homemade gooseberry jam, you might expect something a little more bitter than that which awaits on the palate. This, like all Makana’s meads, has a velvety mouthfeel akin to dessert wine and is recommended with rich meats such as duck.

AFRICAN DRY (12% ABV)

There is a solid acid structure to this mead, and a flavour that is like buttered toast. Of Makana’s meads, this is perhaps the best companion to food.

CAPE FIG (12% ABV)

Best served cold and ideal with a cheese course, this mead displays both sweet and savoury flavours. Floral aromas prevail and there’s a long-lasting aftertaste of dried fruit.

AFRICAN HERBAL BLOSSOM (12% ABV)

A powerful aroma that is herbal, fresh and almost medicinal gives way to complex flavours that conjure up images of an Indian market – think chai and incense sticks.

AFRICAN BIRD’S EYE CHILLI MEAD (12% ABV)

An instantly noticeable but not overpowering chilli bite is the first thing that hits here, though an underlying sweetness offers a nice balance.

15 ml olive oil

10 ml crushed garlic

5 ml chilli powder

2.5 ml turmeric

2.5 ml ground ginger

2.5 ml salt

1 ml ground cumin

5 ml mixed dried herbs

1 kg prawns, shelled and deveined

250 ml sweet mead

SERVES 4–6

The old power station just outside Grahamstown makes an atmospheric home for the Makana Meadery.

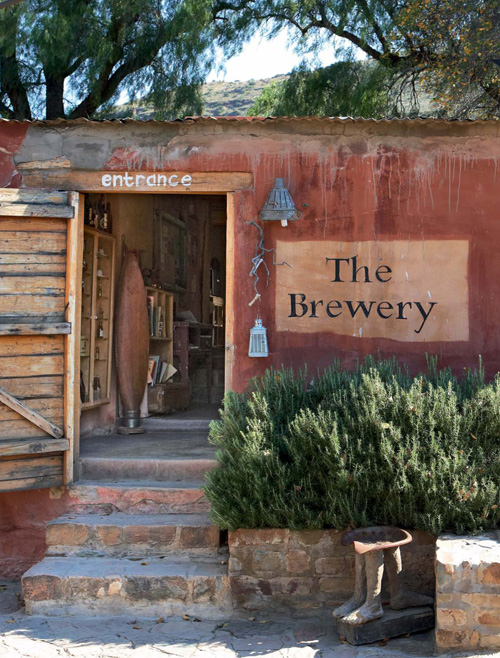

Location: Pienaar Street, Nieu-Bethesda Web: nieubethesda.co.za/brewery.htm Tel: 049 841 1602 Amenities: Light meals, tasting room, coffee roaster, off-sales

Sometimes when you get to a brewery you just want to ditch the car and settle in for the afternoon, and where better to chill out for a day than the dusty Karoo dorp of Nieu-Bethesda. This mountain-fringed town is best known for its community of artists – in particular Helen Martins of Owl House fame – but at the Sneeuberg Brewery and Two Goats Deli you can also sample a little something I like to think of as “edible art”. André Cilliers is not only a brewer – in fact if the only paved road out of town got washed away, he’d be able to survive for some time on his homemade bread, cheese, pickles and, of course, a beer or two to wash it down.

The sandy goat farm is a far cry from André’s former life as an economics lecturer in Cape Town, but there is no longing for the city here. When asked if he ever yearns for Cape Town he looks around and smiles – “Would you?” he enquires. He’s often asked if he gets lonely living out in the sticks, but André laughs at the idea. “I wish I could get lonely!” he says, referring to the near-constant stream of visitors who come to taste his produce.

After moving here in 2001, André quickly realised he would need an extra source of income to support his family and he instantly turned to brewing. “I had brewed kit beers for my friends while I was at Rhodes,” says André. “I’d always enjoyed it so I thought a little brewery would be a nice project.” Sneeuberg – named for the nearby mountain range – was established two years later, first using malt extract and later changing to partial mash brewing (using some malt extract syrup and some malted barley). André has no plans to switch to all-grain brewing in future, largely due to the elevated transport costs involved in getting sacks of grain to this offbeat spot. And if it ain’t broke, they say, don’t fix it – the brewery’s popularity has steadily grown through the years and André is finding that he needs to brew his modest 100-litre batches with increasing frequency. “People come to visit the town but they’ve already seen the Owl House,” he explains. “We’re finding that more people are coming here specifically for us, which is great.” Initially, local people were a little hesitant about the brewery, perhaps envisioning a factory billowing smoke over their untouched town, but now André counts on support from locals as well as tourists.

His beers are found on tap only at the brewery, where you can also buy bottles – recycled Windhoek bottles to be precise – featuring a rustic label whose logo was designed by a local artist. But it’s not just the beer that keeps people coming back – it’s the marriage of beer with two of its most compatible partners: bread and cheese. The eye-catching platters are as tasty as they are pretty, featuring a range of goats’ and cows’ milk cheeses, freshly baked bread and plenty of preserves and pickles, all made on site. Only the smoked Kudu salami comes from out of town, but despite André’s pleas for the recipe, the Graaff-Reinet butcher who produces it won’t spill his secret.

In fact, this salami was what brought Kevin Wood of Darling Brew (see page 59) here in 2007. He arrived with a recommendation to taste the cured meat and left with the intention to set up a brewery of his own, inspired largely by André’s Roasted Ale. André has also helped another brewery to get off the ground – Karoo Brew in Montagu (see page 247).

KAROO ALE (3.5% ABV)

An amber-coloured ale with a powerful hit of granadilla on the nose. The sweet aromas might leave you expecting a sweet beer, but it’s dry and refreshing.

HONEY ALE (3.5% ABV)

Like the Karoo Ale, this has fruity aromas, but dryness on the palate is interrupted by a dose of locally-made honey.

ROASTED ALE (3.5% ABV)

Surprisingly fruity for a dark beer. Expect smoke and roasted flavours in this chocolate-brown-coloured ale, lighter in body than most dark beers.

André’s laidback brewing philosophy perfectly suits the surrounds. “I don’t get too bogged down with details,” he says, referring to both his brewing style and the way he makes the cheese. I’ve got lots of goats and cows to be fed and to milk and lots of other things to do so I’m not too worried about a degree or two of temperature here or an extra few minutes there.”

This ethos clashes with the way many brewers produce their beers, but with each sip of homemade ale and each mouthful of homemade cheese, you adapt to Nieu-Bethesda’s sleepy pace of life, following André’s lead to not sweat the small stuff – at least while you’re in town.

The brewery takes its name from the nearby Sneeuberg range.