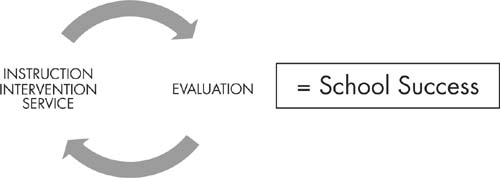

Figure 5. The interrelatedness of evaluation and instruction.

chapter 6 | Evaluating |

EVALUATING emotions and behaviors usually brings to mind a picture of a child being tested by a psychologist or educator, after which a report is written and shared with the parent and school team. The reports may be put into the child’s folder and not used as an integral part of instruction. Or, a team may complete a functional analysis of behavior, but in a way that is not integrated into instruction or not revisited to inform instruction. The way we evaluate a child’s strengths and needs forms the foundation for instruction, and what we know is that there is a need to transform the instruction of kids with challenging behaviors. Therefore, we believe there is a need to transform the way we evaluate a child when she demonstrates behaviors that interfere with her and others’ learning, called interfering behaviors.

The structure and tools provided in this chapter will allow parents to partner with educators for effective evaluation of social, emotional, or behavioral areas. Reading this chapter will guide parents and educators in the evaluation process and answer the following questions:

| Myth | Truth |

| When parents ask for an assessment, the school district has to do it. | When parents ask for an assessment, the school district must consider the request and give the parent a response in writing if the evaluation is refused. That notice should tell the parent why the multidisciplinary team (MDT) decided not to evaluate, what information or reports were used to make the decision, and what information was considered. |

| School districts have to implement my son’s private doctor’s or therapist’s recommendations. |

School districts do not have to accept the recommendation from a privately obtained evaluation. |

| There is a 60-day timeline for reevaluation. |

Timelines for reevaluations vary from state to state. |

| Calling the school principal should be enough to get the school to evaluate my child. |

Parents must consent in writing to assessments and this consent starts timelines. The MDT will decide which evaluations are needed, then seek parent consent. |

• What is evaluation, what are the purposes of evaluation, and how does the evaluation process work?

• How do perspective and bias affect the way we conduct evaluations for children?

• What are legal issues for evaluation?

• What is the role of the parent and child in the evaluation process?

Evaluating emotion and behavior is difficult and complex because there is no one valid, standardized way of measuring behaviors or emotions, and also, there is a wide range of “normal” behavior. Assessment of social, emotional, and behavioral needs also is difficult because evaluation can be subjective and differ by perspective. By gathering data and analyzing that data to figure out the best possible explanation for behavior, the parents and school team apply science and art using a variety of tools. This and the next chapter will help the child’s school team and parents evaluate a child’s needs effectively, which can be a challenging task (Kern & Hilt, 2004).

What Is Evaluation?

Evaluation is the process of making decisions about a child’s school program through analysis of data and evidence collected by parents and school staff. Evaluation and instruction are two sides of one hand; evaluation is not important without intervention, and vice versa. If a teacher teaches without evaluating her children’s needs, or evaluates the children without instructing them, then education is useless.

Most parents and educators think that evaluation and assessment mean the same thing when, in fact, there are important differences. The difference in terms is important to understand, as reflected in Table 4. We will use the term evaluation to mean the collection, interpretation, and analysis of information to make instructional decisions. When a parent requests an evaluation, she will be the most effective advocate for her child if she is aware of the difference between these terms and how the evaluation process works.

The Differences Between Evaluation and Assessment

| Assessment | Evaluation |

| Collecting data | Analyzing the data |

| Gathering information | Reviewing information |

| Testing | Testing not necessary |

| Numbers, facts | Systematic investigation |

| Provides evidence | Opinions, analysis of facts |

| Quantitative | Makes judgment, analyzes value |

What Are the Purposes of Evaluation?

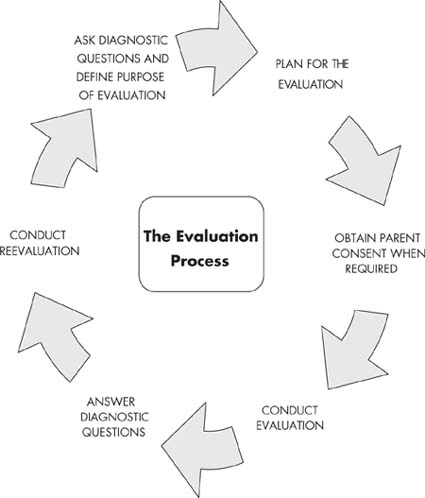

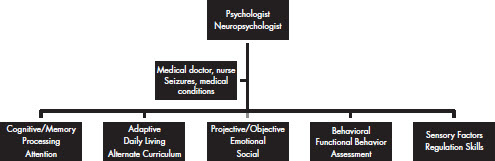

Evaluations should help identify, select, and implement interventions or methods for instruction. Evaluation is only important if it helps determine the right interventions, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. The interrelatedness of evaluation and instruction.

Purposes of evaluation include:

• diagnosis;

• identification of disability;

• to rule out other problems;

• documentation of current functioning, compared with peers;

• recommendation for further assessment;

• defining frequency, duration, and intensity of challenging behaviors;

• understanding the reasons for behavior;

• development of a successful school program;

• recommendations for academic and behavioral interventions;

• recommendations for eligibility for special education;

• analysis of progress in the curriculum or toward individual goals;

• recommendations for eligibility for accommodation or services;

• recommendations for reduction in services or interventions;

• recommendations for additional or different services or interventions; and

• recommendations for scientifically based methods.

Who Conducts the Evaluation?

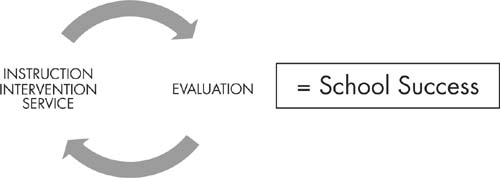

Meet the multidisciplinary team (MDT). Called by many names from school to school, the multidisciplinary team is a group of professionals from multiple areas of expertise, or disciplines, and this group conducts evaluations in the school districts. Each of these professionals is responsible for interpreting, administering, and conducting evaluations, and advising others on their areas of expertise.

Legal Tip

Required members of the MDT who want to be excused from the meeting must get both the parent’s and district’s written consent, and submit a report with their recommendation before the meeting.

As shown in Figure 6, the MDT can involve many individuals. All members of the MDT are important when discussing what types of evaluations to do, how the evaluations should be done, and when considering how evaluations will help develop a child’s school program. In the current and perhaps outdated paradigm, the school psychologist usually is seen as the expert on the team who can administer, discuss, and interpret psychological evaluations. In the new paradigm we set forth in this chapter, the members of the team, with the parents, should work together to develop a comprehensive evaluation plan and execute it and conduct ongoing reviews and revisions based on data. Parents are a critical part of evaluation of behavior and should not be left out of the evaluation process.

Figure 6. Multidisciplinary team members.

Legal Tip

School districts must consider any information provided by a parent; just because a private evaluation report provided by a parent contains a specific recommendation does not mean that the district must do what the private examiner recommends.

Choosing the right examiner. Parents should consider different factors when selecting private, and to the greatest extent possible, school district examiners, including the following:

• cost, payment plans, or reimbursable costs for evaluation;

• personality and rapport with child;

• philosophy of behavior intervention or shared perspective about the child;

• willingness to participate in MDT meetings;

• use of tools and techniques that the school district uses and will accept;

• quality and comprehensiveness: record review, gathering information from multiple sources;

• ability to evaluate the child in the language and form necessary;

• ability to use both formal and informal tools, including classroom observation and/or use of rating scales across different settings; and

• skill and ability to involve the school team in the evaluation process.

There are pros and cons a parent should consider when deciding to allow the MDT to conduct the evaluations, whether to obtain the evaluations privately, or a combination of both. See Tool 6.1 for a list of pros and cons to consider when selecting the right examiner.

Differences school to school. The differences between schools is a real factor that can change perceptions of the MDT. This can be seen when five different multidisciplinary teams study the same child, and come up with five different evaluation plans. When resources are either plentiful or tight, differences from school to school can affect evaluation processes. The reality is that there are vast differences that mostly depend on the financial prowess, resources, and location of the school system or local community.

The members of the MDT may have different perspectives about the causes for or ways to support behavior. Members of the MDT also may have limitations on the type of tests that can be administered, or may have varying degrees of understanding of evaluation processes, methods, and tools. This can affect team dynamics, which can create inconsistency in procedures. School districts usually have a process in place to determine what tests will be purchased and used by the MDT. Regardless of a particular school’s lack of resources, it is critical that the MDT evaluate a child fairly, properly, and comprehensively.

Josef is a student whose school does not have a lot of resources. The guidance counselor is not there full time, and there is no behavior support, social worker, or additional support staff at the school. From classroom to classroom, teachers employ their own behavior systems, and the only schoolwide program rewards students of the month. Suspension or sending students to the administrator’s office for discipline are the most common discipline techniques. Josef is sent to the office at least once a day. His classroom removals and out-of-school suspensions are affecting his schoolwork, and when he comes back to school, his teachers remind him of work to be completed, but little else.

On the other side of the state, Javier’s school employs a wide range of behavior supports, and the teachers all directly teach social skills through group-building activities. A multiple intelligences, strength-based approach is seen throughout the school, including understanding of people who learn differently. Javier is demonstrating challenging behavior, and his school team has met several times, involving his parents and school counselor. When Javier breaks rules, he engages in problem-solving sessions afterward to prevent future problems. In-school detention focuses on teaching material missed and includes direct instruction of problem-solving skills. Javier’s mother communicates with his teachers and counselor on a regular basis.

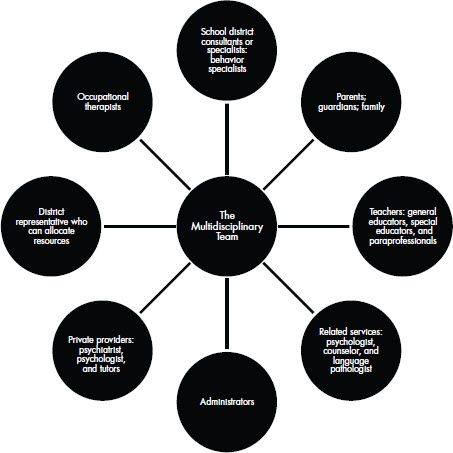

Philosophy or beliefs about behavior can be different from team member to team member, and parents may view behaviors differently than school team members. Further, different schools, or different teams within the same school, can make different conclusions about the same child. It is widely understood that adult perception and expectation for challenging behavior can influence how teachers teach and how children learn. This variability between and within schools obviously can affect how data collection, teaching methods, and services are determined and implemented. This underscores why the evaluation process, shown in Figure 7, is so important. Fair, objective, and thorough evaluation through sound data collection can reduce variability between schools and reduce the effect of perception, judgment, and unfair treatment of children with challenging behavior.

Figure 7. The evaluation process.

The Evaluation Process

One of the most critical steps in the evaluation process is planning for evaluations and formulating the right diagnostic questions. Evaluation planning leads the team to decisions about what tests the child will take, what rating scales will be used, what problems will be assessed, what specialists need to be involved, what special considerations the child needs, and how parents and private therapists or other private providers will be involved. Tool 6.2 provides a list of questions to ask when planning for an evaluation.

Legal Tip

IDEA requires the initial evaluation to be conducted within 60 calendar days of parent consent (signature), but states can form their own timelines. Subsequent evaluations are subject to state regulations’ timelines. Schools can take a parent to a hearing to force evaluations, but schools cannot take a parent to a hearing to force special education.

Parental Participation

Parents are critical partners with the school in the evaluation process. Parents are the first natural teachers and evaluators of the child’s behavior. Gaining parent insight and perspective into a child’s emotional or behavioral functioning is critical, and a parent must be a part of the entire evaluation process, not just one or a few stages. Parents may need training or counseling to understand the nature of the child’s disability, how to work with the school for the child’s progress, or how home-based behaviors may be affecting a child at school. One of the biggest mistakes the team can make is to diminish the importance of parental input or to fail to include parents in each aspect of the evaluation process, especially the functional behavior assessment (FBA). When working with parents, educators should remember that:

• parents can ask to review a formal test before it is used with a child,

• schools should make alternate ways for parents to participate with the school team,

• schools should explain fully the reasons for testing and gain parent consent, and

• parental input should be included in the evaluation.

Legal Tip

Parents are broadly defined under IDEA and can include guardians. A parent can be anyone who is responsible for caring for a child. When a child lives in a group home or other publicly funded place, the public agency representatives should not be seen as parents, unless designated as a parent surrogate.

Perspective and Bias

Evaluating emotions and behaviors is far from a science; it is more like an art that uses a lot of science and scientific principles in the best way we currently understand. Evaluations form the basis for any schoolwide or individual behavior plans, service, or intervention, so it is critical that evaluations are done in a way that is fair, impartial, and based on data, and can be used for making effective teaching recommendations. One test or tool or piece of information should never be used to evaluate a child’s behavior. Evaluation should focus on what can be done to improve the behavior. Evaluation should include use of sound and reliable ways to discover and document a child’s strengths, needs, and current levels of performance.

IDEA is one of several sources that require unbiased, fair, and impartial evaluation. The American Psychological Association, publishers of different tests, professional organizations, states, and school districts also have requirements for evaluation that strive to minimize the effect of human bias or perspective through the evaluation process. Barriers can include the persistent perception of incorrect motive for behavior, incorrect instruction, lack of training, and invisible attitudes that affect team and evaluation dynamics. Scientists have been studying features of evaluation, and in particular, have been interested in the bias inherent in evaluations of social, emotional, and behavioral functioning of children for many decades. Yet, there are very few scientifically based evaluation methods available to assess social, emotional, and behavioral concerns (U.S. Department of Education, 2008).

The range of human behavior and emotions is so vast and variable that perceptions, biases, circumstances, environments, and attitudes can affect how adults see or perceive a child’s behavior. How the child perceives his own behavior, his environment, and his support systems also is important. When behavior problems interfere with learning, belief systems, perceptions, attitudes, and emotional factors are at play. Troubling behaviors often are upsetting to parents and educators, and adults may have different perceptions about a child’s behavior, such as that a child is intentionally disrupting education or that a parent’s lack of support is causing the problem to get worse. These perceptions may affect adult motivation to view the evaluation process as a problemsolving process. This cycle is relevant to the MDT, which works with the parents through the evaluation process. To help the child improve his behavior and, therefore, his academic success, it is imperative that the team and parents join together through a problem-solving perspective, which starts with an effective evaluation process.

Unlike other educational problems, challenging behaviors and social-emotional difficulties often cause emotions from the school team and parents that can cloud how the team engages in collecting information about the behaviors. Much of the time, the conversation about behavior leads to a conversation about the child’s behavior at home, and the team engages in a more personal discussion about emotions and behavior, which can be uncomfortable. There often is unfortunately a strained or poor dynamic of mistrust if a child’s school program is not working or if the child is not receiving the right kind of intervention. If the school team believes that the behavior is intentional or manipulative, and that the reason the child is misbehaving is due to poor parenting or being spoiled, the team will make different decisions about evaluation than another team who may believe that a child’s diagnosed conduct or mood problem must be treated through counseling, teaching of skills, and implementation of positive behavior supports.

Confirmation bias also may affect how the team plans for and conducts evaluations. The idea is that we predetermine a conclusion, and then only test and accept information that agrees with our predetermined conclusion (Grobman, 2008). For example, if a teacher believes that a child is incapable of developing and maintaining relationships, then the teacher may only collect information to prove that. Or, if a teacher believes that a child is unmotivated, she may believe she is seeing behavior caused by a motivation problem within the child that is out of her reach. When the MDT discusses the child using an FBA, testing the hypothesis is vulnerable to confirmation bias. If a team collects data under an incorrect hypothesis about behavior due to biases, team members may overlook data that does not fit their ideas.

Jeremy has been mouthing off to his teachers for months. When he cursed at the principal, the team met with his parent. At the meeting, each teacher took turns discussing how pervasive his “smartmouthing” is, recanting stories through the year of how he constantly talks back. Mrs. Wysdome, Jeremy’s mom, told the teachers that she thinks he is frustrated and has an undiagnosed reading problem. After data collection, the team met again. The behavior specialist from the district reported that the “mouthing” or “talking back” behavior was seen one time per week, over a 3-month time period. The teachers and parent then agreed to conduct a reading assessment. It showed reading problems. So, the behaviors the teachers thought were pervasive turned out to not be happening that often. It was Jeremy’s grumbly personality and academic struggles to which the teachers were really responding.

Formal Versus Informal Evaluation

The differences between informal and formal evaluations lie in how the tools are developed, how they are administered, how they are scored, the qualifications of examiners, and how the results are reported. The following sections describe some of the various types of evaluations a child with EBD may be given.

Neurological and Psychological Evaluation

The most common types of neurological and psychological evaluations used by schools are cognitive or IQ tests and projective or personality tests.

Cognitive or IQ tests. School psychologists focus on school system processes that guide them in evaluation. School psychologists also are obligated under ethics and training requirements of their state and professional associations. A neuropsychologist is a psychologist who has special training in the brain and biological factors. The most common psychological tests are aptitude, cognitive, or intelligence tests. These tests are designed to measure (Weinfeld & Davis, 2008):

• how a child processes information;

• the child’s response to feelings or emotional triggers;

• cognitive strengths and areas of need;

• attention and concentration needs;

• visual motor skills;

• verbal problem-solving skills;

• levels of depression, anxiety, and other emotional responses;

• executive functioning skills such as task initiation, flexibility in problem solving, making transitions or shifting, working memory, and task completion; and

• short- and long-term memory.

Like some standardized tests, intelligence or cognitive tests are given individually. The examiner gives a series of subtests to the child, from writing tasks, to verbal tasks, to visual perceptual tasks, using a variety of tasks to score the child. The child responds in any number of ways to the test items—by pointing, discussing, calculating, writing, or clicking a mouse. The examiner’s manual and the examiner’s training show the examiner when to start testing and when to stop testing. The manual tells the examiner how to set up the testing room, how to document unusual circumstances, how to give directions, score and interpret the number of correct items, and how to interpret scores.

Projective or personality tests. Projective tests were developed by psychologists who believed that unconscious (id, ego, superego) forces are at play, and the subconscious is below the surface and should be uncovered. These tests are said to “project” the subject’s personality onto the test through responses to pictures, inkblots, or other stimuli. Examiners use nondirected questioning and ask the child to respond to incomplete sentences or pictures. Other projective tests incorporate drawing or storytelling tasks.

Without a very high level of training, however, examiners delving into a child’s personality or motivation can be detrimental, especially when the conclusions of the examiners are incorrect. There can be problems with the incorrect interpretation of projective tests, or overreliance on the examiner’s interpretation, so these instruments should be very carefully considered when used to evaluate a child’s social, emotional, or behavioral needs. Also, in the past, and even currently, psychological and other tests are subject to being used incorrectly. For example, these tests have been used as the only test that pigeonholes a student into segregated programs. Findings on a particular test can be interpreted differently depending on the training, perspective, and skill of the evaluator. It’s not the test you use, but how you use the test you’ve got!

Evaluation by the psychologist can include different areas, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Possible areas of evaluation by a psychologist or neuropsychologist.

Achievement and Language:

Curriculum-Based Measurement

For children with challenging behavior, achievement testing is important because the behavior likely has a relationship with academic skills or demand. The behaviors may be affecting the child academically, or the academic problems can be contributing to the behavior. When considering the functional assessment of a child’s challenging behavior, the team and parent should understand the demands of the curriculum, and supplement formal achievement evaluation with curriculum-based assessments. Recent research has shown that there is a link between literacy and language and behavior (Hyter, Rogers-Adkinson, Self, Simmons, & Jantz, 2001; Nippold, 1993; Nippold, Mansfield, Billow, & Tomblin, 2009; Spira, Bracken, & Fischel, 2005). Not only should the MDT consider reading and other academic evaluations, but it should consider whether the expertise of a speech-language pathologist is needed to understand the behavior and to develop a proper, useful functional assessment of behavior.

Occupational Therapy Evaluations

School-based occupational therapists can play an important role in the evaluation of a child’s social, emotional, and behavioral skills (American Occupational Therapy Association, 2009). Because troubled youths have difficulty participating in the classroom and in the workplace, the occupational therapist can be involved in evaluating a child’s needs for the purpose of recommending appropriate school-based services. The American Occupational Therapy Association (2008) acknowledged the need for occupational therapists to partner with the school to provide services for students who are either eligible for special education, or children who are at risk of being identified with an EBD. The evaluation, therefore, should focus on the child’s strengths and needs with respect to mental, emotional, relaxation, and social skills needed for the child to effectively perform an occupation (Quake-Rapp, Miller, Ananthan, & Chiu, 2008). An MDT should convene to plan and conduct curriculum-based and functional behavior evaluations.

Trend Away From Formal Testing

Although formal psychological and other evaluations still play a major role in most school-based multidisciplinary teams, there is a trend that emphasizes a functional, curriculum-based way to effectively evaluate behavior. Problem-solving models such as Response to Intervention and positive behavior supports mirror the evaluation process, as long as one’s framework about evaluation is that it is a problem-solving process that is ongoing. Informal methods are being used to a much greater extent, and this trend has allowed for an opportunity to view evaluation of behavior in a different way. The FBA is scientifically sound and yields valid information about a child’s behavior that informs the development of schoolwide, classwide, and individual interventions. Unfortunately, the FBA has can be seen as a tedious, burdensome task that has little meaning for students, parents, and educators.

The next chapter invites educators and parents to view the FBA in a new way. Unleashing the power of the FBA means that the whole team and parents partner to follow the steps prescribed in the next chapter.

Tool 6.1

Pros and Cons of Private and Public Evaluation

| PROS | CONS | |

| Private Evaluation |

Parents select the examiner; parents interface with the examiner through the evaluation process and may be able to express concern or family history more freely; parents can review results before giving them to the school system; evaluators may select from a wide variety of sound assessments. |

Expense to parents; no guarantee that the school system will accept the findings; school systems may still want to conduct their own evaluations; private evaluators may not be familiar with school system process; proficiency of examiner is important; school system may not approve of an assessment tool that has been used. |

| Public Evaluation |

They are free; school systems are more likely to accept their own findings; various members on the MDT can more easily consult with one another; the examiner may be familiar with the child and vice versa; public evaluations are equally practical. |

Parental involvement may take more work and effort on the part of the parent; examiners may not be qualified and it may be difficult for parents to know qualifications; school system examiners may consult with one another and reach a decision before discussion with parent; evaluation tools and tests may not be available because the school system has not purchased a test; examiners may have pressure from the school system due to directives or trends; school system may only choose which assessment to administer from a narrow list of tools that they have approved. |

Note. Reprinted with permission from Special Needs Advocacy Resource Book, by R. Weinfeld and M. Davis, 2008, p. 98. Copyright 2008 by Prufrock Press.

Questions to Ask When Planning for the Evaluation

• Which evaluation tools will be used to collect information?

• What does the test measure and what groups of students was it tested on (standardization sample)?

• Why are different evaluations being conducted?

• What are the diagnostic questions the evaluation will answer?

• Which educational disabilities does the team suspect?

• What is the definition of any disability suspected?

• Have the parents signed consent for evaluations, after being fully informed?

• Who will conduct evaluations?

• What other information does the team need to answer diagnostic questions?