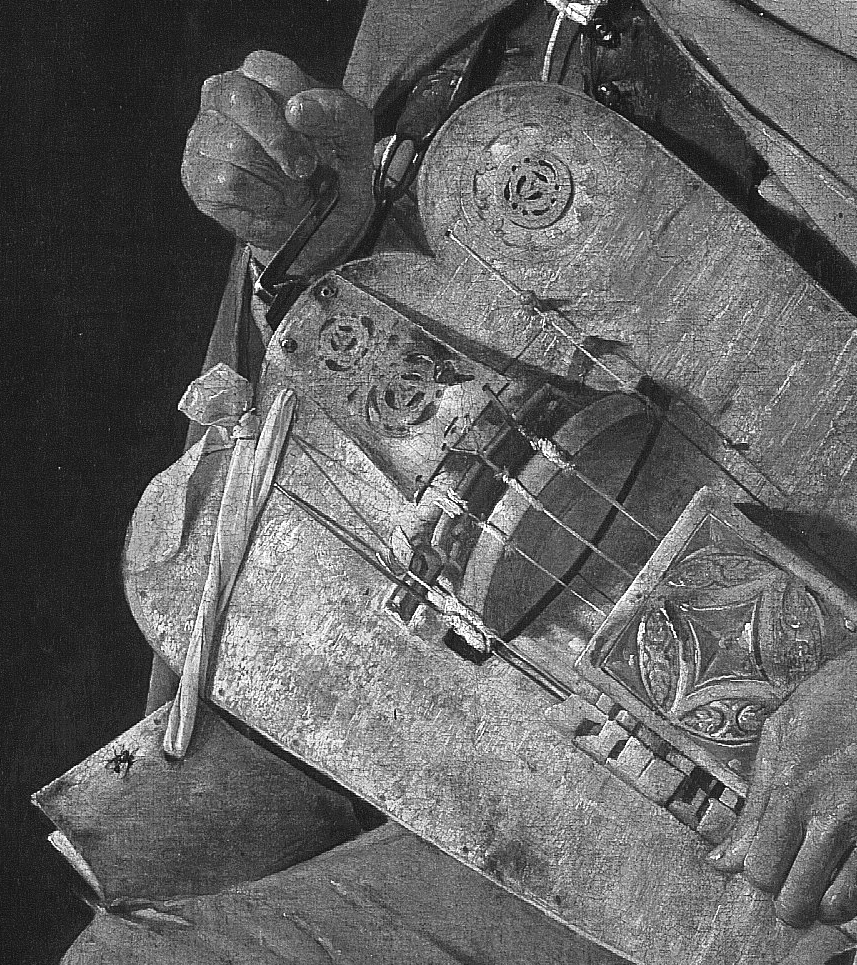

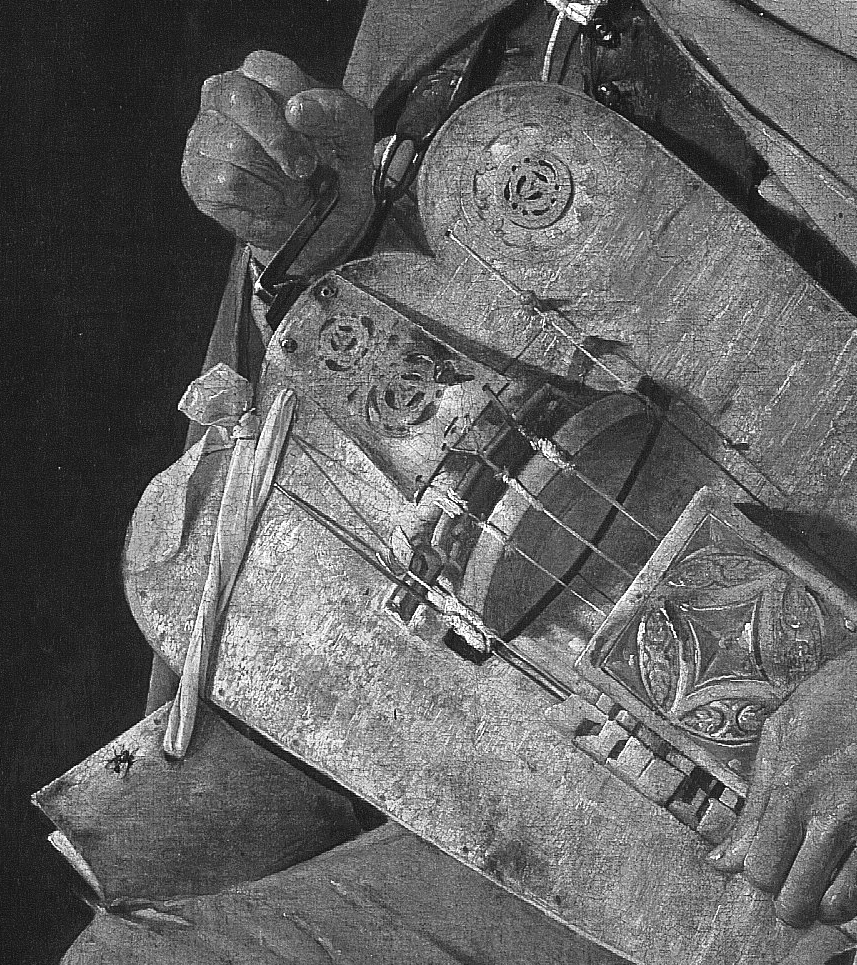

Figure 1. Detail of a fly from Georges de La Tour, The Hurdy-Gurdy Player, c. 1628–1630, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nantes.

All that is visible clings to the invisible. Perhaps the thinkable to the unthinkable.

—NOVALIS, “On Goethe”

The most notable feature of Georges de La Tour’s works is his devotion to the representation of light and its effects, an endeavor whose pictorial rigor also invites reflection on the meaning of vision and its relation to the world. His daylight works startle the viewer with exaggerated depictions of light wherein whiteness casts its pallor over the lineaments of the visible, recalling the artifice of theater and the subterfuge of masks. Submerged in darkness, his nighttime paintings are illuminated by the light of candles, oil jars, or torches whose gleams lend radiance to the objects represented. Even as light brings into view the figures and shapes around it, darkness threatens to dissolve and estrange the apparitions of reality, thus intimating the presence of an inner life and modes of consciousness. La Tour’s valorization of light and his use of dramatic contrasts of light and dark, of chiaroscuro techniques, suggest his possible debt to the influence of Caravaggio as elaborated by his Italian or northern followers.1 At issue here, however, is less the question of determining the nature of such a debt and more the examination of La Tour’s pictorial vocabulary insofar as it functions as a meditation on light, painting, and the nature of vision and the visible.

A more deliberate examination of his works reveals that the apparent primacy of light and seeing is countered by representations suggesting verbal or musical modes of address that entail hearing. How, you might ask, would the presence of words, music, and audition be figured in painting and be reconciled with André Malraux’s remark regarding the pervasive muteness of La Tour’s nocturnes, whose meditative character renders silence audible?2 Anthony Blunt describes the moving simplicity of La Tour’s style as transcending naturalism and attaining a kind of classicism in which all violence and movement are eliminated, granting his work a stillness and silence rarely rivaled in art.3 The stylization of forms through volumetric expansion—the effect of monumentality achieved by the modeling of masses through flat surfaces—lends a sense of stillness to his imposing figures. But this stillness is not mute, since it describes moments of music making, or acts of spiritual devotion, sustained by the murmur of scripture or the incantation of prayer.4 By figuring experiences of audition, whose invisibility lies beyond the purview of vision, these depictions strain the visible sphere of painting.

But the question arises whether painting could be reconceived so that its visual character would reference not only the eye but also the ear.5 This is a condition that painting could suggest but not actually represent, since the beholder’s look would be conflated with the position of the listener. In this study of La Tour’s secular and devotional paintings, I examine the artist’s redefinition of vision as a modality of address that temporizes and thus defers visual impact by its analogy to hearing. Beginning with La Tour’s depiction of blind hurdy-gurdy musicians, this inquiry proceeds to an analysis of his devotional works, of his parallel renditions of St. Jerome and the penitent Magdalene. Reflecting efforts to renew the figurations of spirituality, these works attest to La Tour’s attempts to “reform” the eye as well as to promote a new understanding of the pictorial image. I argue that La Tour’s association of physical vision with blindness and his crossing of vision with modes of a verbal address challenge the vanity of painting—its conceit of abiding in the visible. Throughout, the beholder’s position in relation to this redefinition of vision through its interplay with the word will be at issue, thus enabling further reflection on painting’s enigmatic engagement with the visible.

It so happens that ears have no eyelids.

PASCAL QUIGNARD

La Tour’s inscription of hearing via music and the voice can be seen in his repeated depictions of hurdy-gurdy players, beginning with The Hurdy-Gurdy Player with a Dog (1620–1622, Musée de Bergues) and continuing through four full or half-length works (1628–1630) that include The Hurdy-Gurdy Player, also called The Hurdy-Gurdy Man (c. 1628–1630; Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nantes; see Plate 1).6 Anthony Blunt has noted the popularity of blind hurdy-gurdy players as pictorial subject matter from the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries in France and the Low Countries in both engraving and pictorial traditions.7 However, La Tour’s pictorial treatment of blind hurdy-gurdy musicians is unusual to the extent that his figures are not presented as mere caricatures of social types prone to fraud and deception but as individual musicians plying their craft.8 The imposing scale and the sense of detail, presence, and authority exhibited by these isolated figures invite a consideration of the possible allegorical meanings of these works.9 Depicted as blind—and thus shut out from the realm of the visible—the hurdy-gurdy players nonetheless address the viewer through the suggested representation of the sound of their voices and instruments. As blind subjects, the hurdy-gurdy players can neither return the viewer’s gaze nor function as potential beholders of painting. But their lack of visual access to the surrounding world is supplemented by their vocal or musical address, which reconfigures the beholder’s position into that of a listener. References to music making in general and the drone of the hurdy-gurdy specifically introduce temporal considerations into the image, alluding to music’s transient nature, since music is perceived through time and dissolves in time without leaving tangible traces.10 Given that La Tour’s paintings consistently depict the effects of vision and light, the artist’s deliberate emphasis on blindness and hearing as subject matters of painting intimate a critique of vision as a privileged mode for accessing and witnessing the world. These works question the notion that painting is a medium mutely abiding in the realm of the visible.

Figure 1. Detail of a fly from Georges de La Tour, The Hurdy-Gurdy Player, c. 1628–1630, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nantes.

In The Hurdy-Gurdy Player (c. 1628–1630; Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nantes), the punctual yet fleeting presence of the fly, which has alighted on the removed bridge cover (the insignia of trompe l’oeil painting par excellence), suggests that the visual illusionism of the pictorial image may be at issue (see Figure 1).11 Audible but not visible to the blind musician, the visual representation of this fly inscribes the viewpoint of the beholder into the painting. Alighted on the cover of the instrument (or on the surface of the canvas), the fly marks the visual illusionism of trompe l’oeil painting along with the material surface of the canvas. The timelessness and forceful sense of reality conveyed by this work reflects the triumph of painting over time in its ability to “still” life by immortalizing it as an image, an effect undermined by the fly’s punctual presence. Marking the fleeting nature of time, the fly acts as a memento mori by restaging the conceit of painting as a temporal and thus mortal intervention. This introduction of temporal considerations disrupts the ubiquity of vision. Indeed, the choice of blind musicians as the subject matter of these genre paintings indicates that vision as a mode of apprehension and witnessing is in question. While the blind players cannot see, they can access the world through hearing, a sense whose receptivity is greater than the eyes, which can be shut at will. A note of caution thus insinuates itself into these works, intimating that sight betrays, while hearing imposes itself and commands attention.12 By associating ordinary vision with blindness and by cross-referencing it with hearing, La Tour’s paintings of hurdy-gurdy musicians posit through allegorical depiction the fallibility and deceptive conceits of pictorial representation.

La Tour’s devotional paintings from this period, showing a St. Jerome in penitential self-flagellation, present a stark contrast to his musical scenes. In these parallel renditions of St. Jerome, or Penitence of St. Jerome, also known as St. Jerome with Halo (1628–1630, Musée de Grenoble; see Plate 2); and St. Jerome, or Penitent St. Jerome, c. 1630–1632 (Nationalmuseum, Stockholm; see Plate 3), there is no music being made. Only the rhythmic cadence of a bloodied rope wreaking its punitive vengeance intermittently breaks the silence. The prominently displayed open book on the bottom right along with the cross held above attest to the power of faith attained through the illumination of the Word.13 St. Jerome’s depiction in a scene of penitential self-flagellation replaces the conventional iconography showing him beating his breast with a stone.14 By substituting a bloodstained rope for the stone, La Tour relocates the usual frontal depiction of penitential violence to St. Jerome’s back, which is visually inaccessible to the beholder. The presence of the open book, supported by a skull, mutes the expressive violence of the scene by introducing a contemplative dimension. The inclusion of this book, alluding to St. Jerome’s Latin translation of the Bible, is a reminder of the illuminating power of the Word that brought light and the visible into being. But could this open book also represent an allusion to Cicero, whose rhetoric St. Jerome so admired that he was reprimanded by Christ and flogged by angels in a guilty dream as punishment?15

The glinting, knotted rope, tinged with blood staining the ground, bears the evidence of the marks on St. Jerome’s body, the insignia of his spiritual aspiration and his guilt at having delighted in secular words instead of the divine Word. Intended to foster identification with the suffering of Christ, the gesture of penitential self-flagellation is here conflated with the guilt expressed by Jerome in response to the seductiveness of the rhetoric of Cicero. His pagan rhetoric represents an art of speaking whose powers of persuasion competed with the scriptures, thus distracting Jerome in his pursuit of his spiritual mission. The attainment of spiritual insight is a response to a call, an awakening of the voice of conscience that overcomes the artful seduction of rhetoric and colorful images. Hearing the divine Word implies not only the recognition of being its addressee but also the obligation to incorporate this address into the flesh. The mystery of Christ’s incarnation, of the Word become flesh, thus haunts both the fate of the representation of the body and the painterly world it inhabits.

St. Jerome’s self-administered reprimand traces the divine address as a violent imprint, resonating with the resounding conviction of the Word made audible through the wounding ruptures of the skin on his back. The manifest painterly muteness of these two works is inflected by the presence of sound, which challenges the visual grasp of the beholder. Alluding to a mode of apprehension that escapes painting’s representational purview, this appeal to hearing questions the power of vision. The depiction of St. Jerome’s body tests the visual grasp of the beholder by combining gestures that imply two different modes of subjective expression: contemplative meditation and active flagellation. St. Jerome’s gaze is averted, and he is meditating on a cross held in the left hand, but St. Jerome’s right hand exacts painful penance in the presence of the Word. The difference between these two hand gestures bears witness to the intervention of the divine address that subverts subjectivity by impeding its actions as a unified consciousness. St. Jerome’s submission to the Word dispossesses his body of the worldly logic by redefining it as the ecstatic site of spiritual transfiguration.

In the lower left of both the Grenoble and Stockholm versions, the knotted, bloodied rope, which is the instrument of St. Jerome’s penitence, visibly marks the ground. In the Stockholm version, the drops of blood staining the ground are further emphasized by the prominent redness of a cardinal’s large hat, with knotted tassels visually intersecting the bloodied rope of the scourge. In both works, St. Jerome’s body is framed by the redness of the large cloth draped over his left arm, bringing allusions to his martyred body into the register of the visible. Unavailable to the beholder, or to painting, his martyred back is the invisible canvas bearing the painful marks of his expression of faith. Tracing St. Jerome’s spiritual conviction in the divine Word, this virtual but invisible aspect of the painting competes with the reality of the depicted body and the visible world. These allusions to painting are subliminally emphasized by the knotted red tassels on the left, which look like painters’ brushes, and the draped red cloth on the right. The drops of blood emanating from the saint’s body, which are also drops of red paint, mark the conjunction of the body with the medium of painting. Associating the mortification of the flesh with the gesture of painting, La Tour’s representations of St. Jerome remind the beholder of their shared vanity in the face of death. These works suggest that the fate of the body, like that of painting, can be redeemed only through spiritual transfiguration. Based on spiritual insight, such attainment implies a new way of seeing and thus a different understanding of painting rescued from the blinding familiarity of vision and its misplaced faith in the visible.

A brief reflection on La Tour’s parallel depictions of St. Jerome in the versions of c. 1628–1630 and c. 1630–1632 is in order, before proceeding to his other works. As noted earlier, these versions repeat the same subject matter with small variations in the presentation of figures and in shifts of the tonality of light, but to what end?16 Jean-Pierre Cuzin attributes their production to La Tour’s success as an artist: He was being asked to make paintings that resembled works previously executed.17 Further inquiry reveals that La Tour’s use of repetition reprises a pictorial practice that enjoyed some currency in the early modern workshop, as Maria H. Loh has shown in her analysis of Titian and early modern Italian art.18 Evidence as regards the pertinence of this practice to French art is provided by the French art critic Roger de Piles (1635–1709), who observes in 1699 that “there is hardly a single painter who has never repeated one of his works either because it pleased him or because someone asked him for a similar work,” and he compares Titian’s repetition of the same painting seven to eight times to how “one performs a successful comedy.”19 Having achieved a successful assemblage of all the elements, the painter repeats the same composition, leading De Piles to conclude that “there is no doubt that they are all Originals.20 De Piles’s validation of pictorial repetition relies on an analogy based on dramatic performance, leading to the question whether the idea of a verbal performance could illuminate La Tour’s pictorial practice.

The variations in tonal scope of the parallel versions of St. Jerome suggest a treatment of light in the mode of an utterance, since the reiteration of its radiance engenders different subjective affects or moods. La Tour’s pictorial strategy reprises the use of parallelism in the Gospels, which present similar versions of Christ’s life, actions, and words through the three accounts of the Apostles, St. Matthew, St. Mark, and St. Luke.21 Designated as the Synoptic Gospels, from the Greek syn, meaning “together,” and optic, meaning “seen,” these accounts provide ways of “seeing” produced through the iterative overlap of parallel acts of witnessing.22 These parallel scriptural accounts suggest that no single act of attestation, witnessing, or representation is sufficient or complete in itself in referring to the divine prototype. Not only does the adoption of an iterative strategy reflect the importance of the word to La Tour’s pictorial enterprise, but it can also be seen as a response to the visual problems posed by the image for Trent and after. Despite some ostentatious displays of pictorial mastery, the repetitive character of these parallel versions undermines the visual uniqueness of the image. Recalling scriptures, it relegates these images to a derivative, provisional condition as exemplars of a prototype of which they would provide but a circumstantial and thus partial account. Marked by the crossover of word and image on the level of content, La Tour’s parallel versions also reflect the effect of this strategy on the pictorial level, redefining the way images are seen and understood.

Whisper in my heart, I am here to save you.

ST. AUGUSTINE

In their tenebrism and contemplative mood, La Tour’s devotional nocturnes, referred to as nuicts, produced between 1630 and the mid-1640s, capture a spiritual reflection wherein darkness and light become the vehicles of the encounter of the mortal and divine worlds.23 The use of chiaroscuro in these works emerges less as a stylistic conceit than as the visible trace of an encounter bridging the human and divine realms. The focus of analysis now turns to nocturnes, to four paintings commonly designated as “Repentant Magdalene,” depicting Mary Magdalene clothed and in profile, absorbed in meditation. Much favored as a pictorial subject during the Catholic Reformation, Mary Magdalene is represented as the consummate sinner who gave herself wholly to the pleasures of the senses only to achieve heavenly glory through penance and inward contemplation. According to Jacobus de Voragine’s Golden Legend, which continued to be influential through the seventeenth century, Mary Magdalene was “known for the way she gave her body to pleasure—so much so that her proper name was forgotten and she was commonly called the sinner.” The confusion and ultimate eradication of the sinner by her sins, figured through the loss of her proper name, became redeemed through penance “because for every pleasure she had enjoyed she found a way of immolating herself.”24 Voragine noted that her sins were forgiven because of the purity of her love, as attested to by Jesus’s claims to have seen into her heart. Voragine’s light-filled vocabulary in describing Mary Magdalene and his insistence on the exemplary role her repentance played in illuminating others provide a discursive framework for elucidating the visual details and iconography of La Tour’s paintings.

Voragine explained that, having chosen the path of inward contemplation, she is called the “enlightener” or light giver because she received the light with which she enlightened others: “Since she chose the best part of inward contemplation, she is called the enlightener, because in contemplation she drew draughts of light so deep that in turn she poured out light in abundance.”25 Mary Magdalene’s spiritual enlightenment illuminated her body, and her radiance enlightened others like a lantern shining in the dark.26 In the Book of the City of Ladies (c. 1405), Christine de Pizan underscored Mary Magdalene’s significance by noting Christ’s wish that “so worthy a mystery as his most gracious resurrection be first announced by a woman” and that he commanded her to report and announce it to his Apostles.27 From its biblical origins onward, the legend of Mary Magdalene privileges her position as an eyewitness to the Crucifixion, the disappearance of Christ’s body from the tomb, and the subsequent reappearance of Christ resurrected.28 In La Tour’s paintings, her unique position as eyewitness to Christ’s passage from martyrdom and entombment to his resurrection serves as a privileged vehicle for a meditation on the relation between the visible and the invisible in both spiritual and painterly terms.29

In The Magdalene at the Mirror, also referred to as The Repentant Magdalene (c. 1635, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; see Plate 4), Mary Magdalene’s face in profile is propped on her hand; her other hand touches a skull reflected in a mirror turned toward the beholder. The skull is illuminated by the flame of an oil lamp concealed behind it, revealing but the tip of its tremulous flame, slightly bent as if touched by the exhalation of her passing breath. The flickering flame carries multiple associations in emblematic traditions, where it is a reflection on the brevity of human life as well as a figure for conversion.30 Magdalene’s contemplative gesture is disconcerting to the extent that the beholder has trouble following the precise object of her gaze, its outward or inward spiritual referents. The unfocused character of her gaze is not reducible to either absorption or introspection, since it lacks traces of self-possession or self-consciousness implied in worldly concerns. The sense of melancholy pervading the image highlights Magdalene’s receptive vacancy, her absence to herself as she gives herself over to spiritual contemplation.

Failing to address the beholder, Magdalene emerges as the witness of a divine address whose muted presence is suggested by the voluminous tome resting on the table. The inconsistency between Magdalene’s gaze (who looks without necessarily seeing) and her pointed fingers resting on the vacant orbits of the skull supported by the book inscribes an ambiguity into the painting. While her contemplative outlook refers to spiritual illumination, her touch of the skull’s empty orbits points to the vacancy of death. Reflected in the mirror, the skull’s shining orbit counters the conceit of the beholder’s gaze with a reminder of death, a warning whose blinding effects extend to both vision and painting. The magnified depiction of this blank gaze in the mirror exposes and reproves the act of seeing by revealing its deceits, which are staged through painterly illusion. Serving to reveal the vanity of painting, it undermines the conceit of sight with a pointed reminder of the blindness and deception underlying its painterly manufacture, artifice, and illusion. The portrayal of the closed book, whose visual appearance is but incidental to its function of serving as an instrument for spiritual reflection, counters and contests painting’s ability to shed light on things. By inscribing allusions to words, most likely those of scriptures, the book’s voluminous presence underlines its importance in providing verbal cues and clues for understanding the pictorial image.

Traditionally, mirrors are emblems of worldly vanity, but in the early modern period they were also spiritual emblems of Christ’s double nature, the material opacity and darkness of his mortality subtending the brilliant clarity of his divinity. These spiritual meanings associated with mirrors emerged from and reflected the influence of scriptural writings, Neoplatonic texts, and the writings of the church fathers.31 In philosophical traditions dating back to Plato, mirrors were associated with painting in a derogatory sense, given painting’s illusionism and manufacture of idols.32 But in early modern theoretical writings on art, ranging from Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) to Caravaggio and Samuel Dirks van Hoogstraten (1627–1678), this trope is retooled, and the mirror emerged as a key metaphor for the pictorial image.33 A close examination of La Tour’s depiction of mirrors reveals that they are not mere accessories: They prove to be essential both to a spiritual and a secular understanding of these images as paintings. In The Magdalene at the Mirror, the mirror is tilted at an angle to make available to the beholder a partial reflection of the skull, presenting a view that invites scrutiny.34 This mirror reflects neither the vanity of Mary Magdalene as depicted subject nor the visual logic of painting, since it presents a frontal view of the skull that challenges both visual and pictorial principles. By reflecting the front of the skull, which is turned away from the mirror, instead of the back, which is facing it, this mirror confronts the beholder with a view that is physically impossible and that lacks pictorial verisimilitude.35

The image in the painted mirror presents a view that the mirror cannot actually show, casting its faithfulness into doubt. This may be seen as a comment on the duplicity associated with mirrors in general, since the faithfulness of their reflections dissimulates the cunning of optical inversion. Indeed, insofar as this painted mirror depicts a reality that does not appear to exist, it functions as a metaphor for the duplicity associated with painting.36 La Tour’s representation of the mirror image is not reducible to an ordinary reflection; such a projection would require the mirror’s displacement to the front of the skull. However, this position is already occupied by Mary Magdalene, who does not look but “sees” through the touch of her fingers on the skull’s blind orbits. She is depicted as a “seer” in the position of “seeing” from a vantage point unavailable to the mirror, thus suggesting that the mirror depicts her “vision” instead of a mere reflection of the world. The mirror image thus bears witness to a spiritual way of seeing, attenuating the visual by showing the blindness attendant to both vision and painting.

La Tour’s pictorial approach relies on the mirror’s figurative elaboration in the New Testament, where it stands in for the illuminating power of the Word. According to St. Paul: “But we all, with unveiled face beholding as in a mirror the glory of the Lord, are transformed into the same image from glory to glory, even as from the Lord the Spirit” (2 Cor. 3:18).37 A regional contemporary of La Tour, Father André de l’Auge, evokes this formulation by describing Christ’s Gospel as a “very clear mirror of the glory of God,” by which, when we are reflected in it as in a beautiful looking glass, “we are accidentally transformed and illuminated as if by an emanating reflection of the light of Jesus Christ.”38 This analogy that figures the Gospels as a mirror through which the reader is illuminated and transformed by the reflection of the light of Christ invites further consideration of the mirror’s reflective and transformative potential. Focusing on the practitioner’s relation to scriptures, St. James argues that spiritual reflection requires active self-transformation rather than a mirror’s mere capture of appearances: “But be ye doers of the word, and not hearers only, deceiving your own selves. For if any be a hearer of the word, and not a doer he is like unto a man beholding his natural face in a glass: For he beholdeth himself, and goeth his way, and straightaway forgetteth what manner of a man he was” (James 1:22–24).39 Spiritual practice implies transforming one’s manner of being to reflect the Word, instead of losing sight of oneself in passing reflection. Pitting the mirror’s visual mode of reflection against the Word’s spiritual powers of enlightenment, The Magdalene at the Mirror places the beholder at their crossing. The beholder must traverse the painting’s material opacity in order to “see” across and gain illumination. This traversal holds out the promise of a transformation, which implies a radical transfiguration of one’s being. The infidelity or cunning ascribed to the mirror’s profane modes of abiding in the visible is redeemed through the spiritual power of the Word and its ability to transform a mere image into a new manner of being and feeling.

Mary Magdalene’s profile and meditative posture suggest a “planar effect within depth” where the lateral associations of elements separate in virtual depth collapse their earthly spatial associations.40 This effect is further emphasized in The Magdalene with Two Flames (c. 1640–1644), also known as The Penitent Magdalen (c. 1640, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; see Plate 5), where her profiled face mediates a passage between the look of the beholder and her own look off into space. Commenting on the profile as a symbolic form, Meyer Schapiro observed: “It seems to exist both for us and for itself in a space virtually continuous with our own, and it is therefore appropriate to the figure as symbol and carrier of a message.”41 Marking a threshold between light and dark, Mary Magdalene’s monocular profile and gaze suggests a different understanding of vision and the visible. Her address into the tenebrous void, which is depicted as if she were listening to something rather than merely “looking” into it, activates the darkness by infusing it with meaning. Crossing from the visible into the penumbra of the invisible, La Tour’s representation of Mary Magdalene’s gaze questions the logic of vision by exposing the limits of beholding as it strains to achieve spiritual insight.

In The Magdalene with Two Flames, the skull is more stylized pictorially and is depicted as resting on Mary Magdalene’s lap. There is poignancy in this proximity, since the skull is the residue of a body whose time has run out, but as an object of contemplation it holds out the promise of eternal life. The coiled pearls strewn on the table, as well as the abandoned jewels on the floor on the lower right, stand as pointed reminders of the vanity of her former worldly preoccupations prior to her conversionary turn. These elements introduce a temporal dimension into the image by marking Mary Magdalene’s precipitous but also irrevocable shift toward spiritual enlightenment. Complementing the mirror and the skull (which we saw in The Magdalene at the Mirror), they reiterate the theme of the memento mori, of the passing nature and vanity of worldly things. Illuminated by her belief in the divine Word, as indicated by the turning of her gaze into the darkness beyond her and her fingers crossed as if in prayer, Mary Magdalene absents herself from the visual space she inhabits. Presenting the emergence of religious conviction based upon a meditation on time and death, this painting suggests the accession to spiritual insight against the seductive glitters of the visible world.

To the right, on the table, stands a gilded mirror reflecting the flame and the back of the candle.42 This radiant display of light is enhanced by the candle’s mirror image and the gleams reflected in the mirror’s ornate frame, echoing and magnifying the flame’s power to give light. This compelling detail of still-life painting presents a mirror that, with apparent ostentation, displays its virtue and cunning in providing a masterful visual duplicate of the physical world. Through its specular conceit, this lavish mirror introduces a disjunctive, alternative space into the painting, enforcing its separate standing through its decorated frame. But to what end precisely? The lustrous glints of the mirror surface, projected as luminous traces on the edges of its frame, emphasize the visual illusionism that mirrors manifest and paintings ostensibly celebrate. Such allusions to the vanity of painting as an extension of worldly vanity serve as reminders to the beholder of the difference between light as a source of physical illumination and the light of spiritual illumination.43 In The Magdalene with Two Flames, the beauty of the reflection of the lighted candle as a detail of still-life painting is juxtaposed with Mary Magdalene’s internal reflection, her spiritual beatitude. Duplicating the frame of the painting in a play of mise-en-abyme, the mirror marks the crossing between the plane of outward reality and the plane of inner life.44 Functioning as a “model of transformation of matter into form and as an instrument of resemblance,” the mirror bears witness to the “presence of an immaterial reality in the visible.”45 Alluding to the presence of the invisible in the visible, the painted mirror acts as a device that figures the potential crossover from physical to spiritual vision.

The duplication of the candle and its flame by the mirror image within the frame of the larger painting also reveals a broader reflection on vision and painting, since, according to Merleau-Ponty, “the mirror image anticipates, within things, the labor of vision.”46 By expanding the human capacity to see, the mirror “can show the apparition or possibility of seeing or reflecting a figure in a reversed position despite the eyes’ physical limitations.”47 The crossover and reversibility of the candle into its mirror image relies on a chiastic movement that complements rather than merely duplicates ordinary vision.48 Used to illustrate or highlight details of particular importance in the Old and the New Testament, chiasm or chiasmus refers to a figure of speech in which “a sequence of ideas is presented and then repeated in reverse order,” resulting in a “mirror effect as the ideas are ‘reflected’ back.”49 La Tour’s pictorial use of the mirror recalls its biblical rhetorical function but transposes the relevance of its chiastic projections to the visual realm of painting. The crisscross structure and inversion that describe the mirror as a chiastic device provide a model for the workings of painting understood as spiritual practice. Namely, the mirror figures painting’s duplicative powers along with that which escapes and resists through inversion the grasp of ordinary vision.50 Thus in addition to figuring the labor of vision, the mirror in The Magdalene with Two Flames (like the mirror in The Magdalene at the Mirror) also serves as a metaphor for the labor of painting. The interplay of the image of the mirror with the image in the mirror attests to painting’s struggle and transformative potential in its efforts to mobilize material means in the pursuit of spiritual attainment.

To meditate is to consider in one’s mind, and as it were, to paint in one’s heart.

ANTOINE SUCQUET, Via vitae aeternae (1620)

Two related nocturnes, The Magdalene with the Smoking Flame (c. 1636–1638, Los Angeles County Museum of Art; see Plate 6) and The Repentant Magdalene, or Penitent Magdalen, also known as The Repentant Magdalen with the Night-Light (c. 1640–1645, Musée du Louvre, Paris; see Plate 7), reiterate the devotional topic of the penitent Magdalene. Like La Tour’s earlier St. Jerome paintings, these works visually echo each other, with slight variations in the cropping of the image, the disposition of the body, and the still-life elements in the background.51 Although they are almost identical in their formal presentation, the most notable difference between these two images is the brightness and tonality of light. In The Magdalene with the Smoking Flame, the brighter smoking flame generates more dramatic contrast with the warmer redder tones of the painting overall as opposed to the cooler greenish-brown and gray tones of The Repentant Magdalene. The visual parallelism of these works, like the renditions of St. Jerome, reprise in a pictorial register the reiterated accounts of the same events in the Gospels. The shift in the tonality of light imparts to each work a particular affective tenor suggesting parallel but different ways of witnessing the same event. Attesting to the tenor of consciousness, a state of mind made possible by a change of heart, the variations in physical color are indices of spiritual illumination marking the ardor and intensity of faith.

These representations of Mary Magdalene lack the visual and worldly seductions presented in the previous two versions discussed. The absence of mirrors or glitter of worldly jewels removes from these paintings the seductive traces of ornamentation and the explicit allusions to the radiance of the visible. The lack of allusion to expanded spaces that are provided by mirrors serves to highlight the intensity of mental concentration within the visionary space of contemplation. The motif of the knotted rope, girded around and falling away from Magdalene’s body, submerged and miniaturized as a twisted candlewick inside the illuminated jar, only to reemerge winding about the cross, visually ties these elements together. The body, the lamp, and the cross are bound in a circuit that sustains the encounter with the divine, since burning light and girded loins are insignias of vigilant receptivity to the coming of the Lord (Luke 12:35–37).52 In addition to incorporating these biblical allusions, La Tour’s depictions of the knotted rope recall his earlier paintings of St. Jerome, where self-flagellation dramatized penance through self-mortification, mutely staging the incarnation of the divine Word. Commenting on these paintings, François-Georges Pariset observed that the lowered blouse on her shoulders and the penitential rope, bearing some reddish stains in The Magdalen with the Smoking Flame; and the perceptible reddish stains on the lowered blouse in The Repentant Magdalen provide subliminal visual traces of Magdalene’s repentance.53 As in La Tour’s St. Jerome paintings, it is her invisible back and shoulders bearing the marks of penance that constitute the true canvas or mirror for the representation of spiritual enlightenment. But these are traces to which the beholder is blind, since they cannot be seen, only inferred. Reflecting the injunction of the Word, these penitential marks emerge as the invisible substrate of that which painting cannot depict by abiding in the visible.

The Magdalen with the Smoking Flame and The Repentant Magdalen present us with a reflection on the nature of vision and painting that in the previously discussed works were staged through the use of the motifs of mirrors and frames. But in these two works, Mary Magdalene’s gaze enacts the gesture of beholding by looking yet—given her contemplative disposition—not necessarily seeing the objects traversing her field of vision. The object of her inward contemplation competes with the beholder’s visual appreciation of the still-life scene depicted to her left. The bright flame issuing from a thick wick floating in a glass oil jar illuminates the still-life scene, comprising two holy books and a penitential knotted rope wound upon a wooden cross precariously poised on the table’s edge. The transparent oil jar suggests a biblical allusion to the Parable of the Foolish Virgins, who missed their assignations with the divine bridegroom for lack of oil in their lamps (Matt. 25:1–13). The pictorial still lifes in the background of these works serve as reminders of the conceit of painting and its ability to capture and immortalize the changing semblance of the visible world. They expose painting’s powers to duplicate appearances through verisimilar rendering, thus attesting to technical rather than spiritual virtuosity. The inclusion of these still lifes highlights their metapictorial function, that of commenting on the nature of painting and its modalities of representation.

These allusions to painting as representational art are further reinforced in The Magdalen with the Smoking Flame, since the back rim of the glass oil jar shows a truncated reflection of the flame. Although the oil jar in this version is mostly smoky, the back rim acts as a reflective surface and therefore as a stand-in for the mirrors represented in the paintings previously discussed. In The Repentant Magdalene, in addition to the flame’s truncated reflection on the rim and the visual magnification of the wick (as if viewed through a looking glass), we also see, in the bottom section of the glass oil jar, a book’s reflection (see Plate 8). The juxtaposition of the book with its reflected image in the oil jar brings into conjunction the visual semblance of the book as purveyor of the divine Word and its visual reflection as an ordinary object devoid of sacred connotations. Whereas the book holds out the promise of spiritual illumination, its reflection in the glass forecloses that possibility, since its meaning is exhausted by its visual appearance. This duplication of the book through its reduction to a mere image serves as a reminder of the dead-end character of the pictorial image and its mirror illusionism.

However, this double representation of the book as purveyor of the Word and as visual reflection also suggests a larger allusion to the representational powers of painting because it implies, through doubling, a reflection on the production and artifice of the image as simulacrum. La Tour’s treatment of the still-life background represents the labor of painting by alluding to its capacity for duplication while also celebrating the mastery of the painter’s craft through the display of virtuosity. As a result, while denouncing painting’s visual conceits as a form of blindness for religious purposes, La Tour’s works also uncover within painting a mute thinking that illuminates the labor of vision in a secular sense. The efforts to elaborate a spiritual understanding of pictorial images also serve to reveal their conceptual underpinnings and potential. In the repentant Magdalene paintings, this conjunction of sight and insight is precariously poised, just like the cross lying on the table’s edge, marking the liminal realm of conversion at the crossing of the divine and profane worlds.

While spiritual vision suspends the radiance of the visible through its interface with the Word, this renunciation holds out the promise of a new way of seeing. But this new way of seeing is not purely spiritual but also painterly because it requires a new understanding of the image redefined through the interplay of seeing and hearing. La Tour’s paintings thus celebrate the enigma of visibility—an enigma precisely because its worldly radiance is grounded in conditions that escape its representational logic. By revealing the conditional nature of the visible on determinations that escape its purview, La Tour’s works also emerge as meditations on the nature of painting. They serve to alert the beholder to the reality that seeing is not merely a form of visual possession or a grasp at a distance but also a form of radical dispossession implying surrender and receptivity. This erosion of subjective agency reflects an understanding of vision that includes, along with the capacity to encounter the visible world, the recognition of being its addressee. This decentering of the primacy of the viewing subject opens up new ways of thinking about vision. It adumbrates an understanding of vision that implies a dispossession of being, such as we encounter in Merleau-Ponty’s late philosophical observations regarding vision in Eye and Mind (1961): “Vision is not a certain mode of thought or presence to self; it is the means given me for being absent from myself, for being present at the fission of Being from the inside—the fission at whose termination and not before, I come back to myself.”54 Undermining the self-presence of the seer, the labor of vision marks a fissure within being, decentering the subject through the evidence of its indelible embeddedness in the world. Thus it would seem that the beholder may be beholden in ways that invite us to rethink the nature of painting and its modes of abiding in the visible.