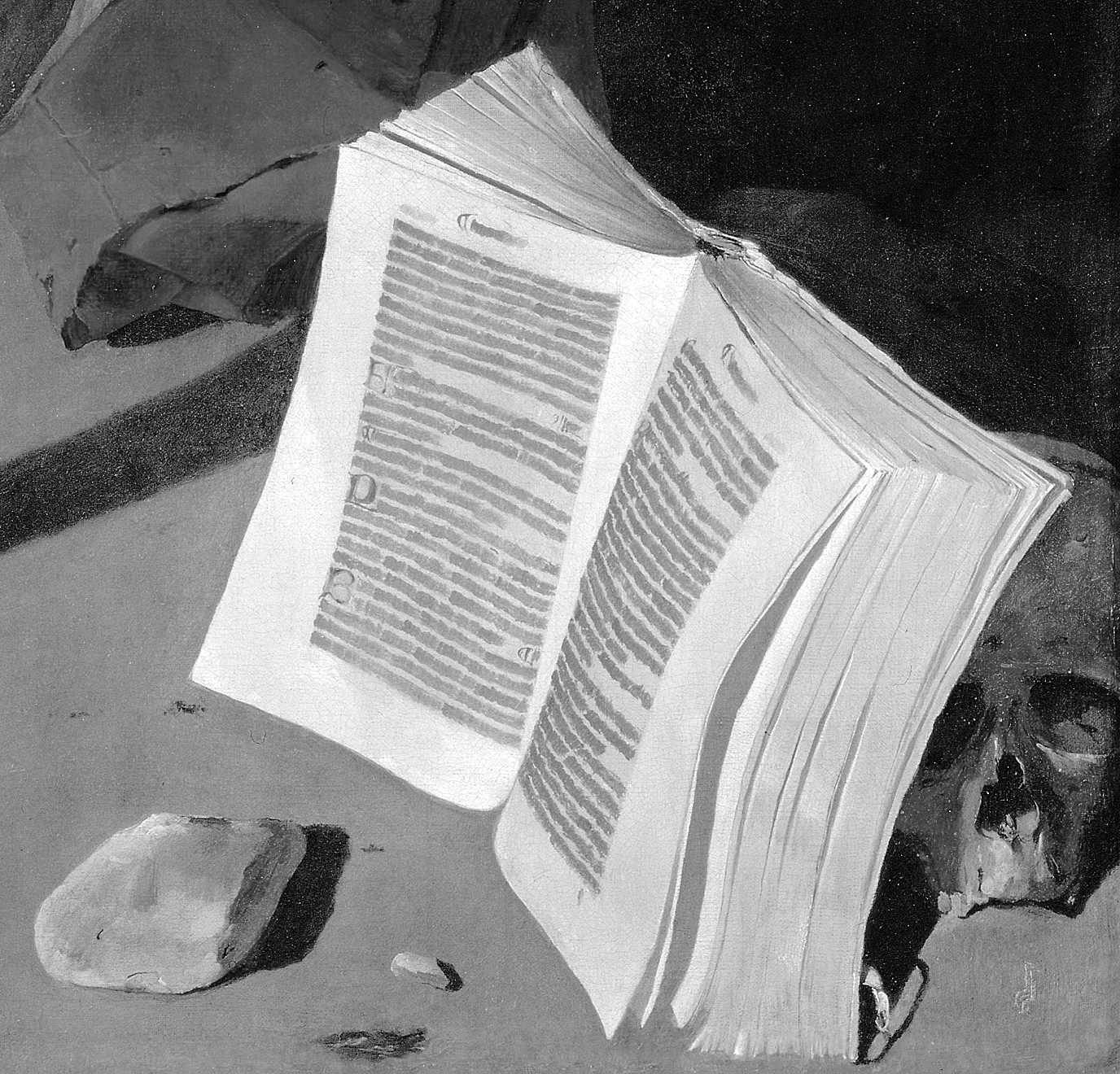

Figure 2. Detail of a book from Georges de La Tour, St. Jerome, c. 1628–1630, Musée de Grenoble.

La Tour’s paintings are images that are enigmas.

—PASCAL QUIGNARD

Many of Georges de La Tour’s devotional paintings are populated by the presence of books that constitute veritable “still lives” in the midst of already still and quiet images. In his treatments of Mary Magdalene, books are often depicted closed and piled haphazardly on top of one another; they are placed near a cross, a penitential rope, or a skull—insignias and privileged instruments of seventeenth-century Christian spiritual practices. Although muted by their inaccessibility, these painted books whisper in the silence of the night, attesting to crises of consciousness or moments of repentance, conversion, or prayer in the Christian turn to God. When books are represented as opened, for example, in La Tour’s paintings of St. Jerome, the pictorial verisimilitude of these books is so convincing that the beholder is invited—even compelled—to read these painted texts on display (see Figure 2). However, the viewer is thwarted in this attempt, for the written text dissolves into pure lines, thereby bestowing upon painting only the semblance of an articulated gesture. While attesting to the painter’s virtuosity in capturing the visible semblance of books, these images also resolutely celebrate the Bible as divine word and source of spiritual illumination.

There appears to be even more at stake in La Tour’s depictions of books, however, since so many of his paintings show the act of reading. Why would La Tour repeatedly insist on the representation of reading as a subject matter for his paintings? And, as Garrett Stewart noted in his book The Look of Reading: Book, Painting, Text: “Why labor so intensely to evoke the unpicturable space, and often the illegible page, of textual fascination?”1 After all, given its absorbed and introspective character, the act of reading does not easily lend itself to visual flourish or pictorial bravura. Quite the contrary: Based on verbal expression, reading opens a window onto another reality whose virtual and sometimes visionary or imaginative character competes with or sidesteps the visible evidence of the world at hand. While relying on the sense of sight to access words, the experience of reading no longer depends on the look of the words after the onset of print culture. Made uniform and therefore shorn of its graphic individualities, the printed text more easily facilitates reading and meditation.2 Do La Tour’s representations of books and the act of reading constitute a way to question the preeminence of vision and the visible realm? Could reading serve not just as a representation of an intellectual quest but also as a figure of faith, a search for spiritual illumination that tests the visual realm of painterly expression? This chapter shows that La Tour’s devotional nocturnes open within the visual experience of painting a visionary, affective space where sight gives way to spiritual insight. In addition to promoting religious sentiment, however, such spiritual reflection also becomes the conduit for a meditation on the representational limits of painting.

The devotional paintings of La Tour tangibly explore the problem of visualization or of representing spiritual insight in a visual register. This attempt to interrogate the visual thrust of La Tour’s images is inflected by the iconographic economy and minimalism of his paintings, since the lack of décor and the scarcity of depicted objects requires deciphering rather than just observation. François-Georges Pariset remarked that the very lack of objects represented in La Tour’s paintings renders each one significant; this sense of visual parsimony is reinforced by La Tour’s appeal to a “reduced registry of colors that have a symbolic signification.”3 Thus, to speak about deciphering the visual meaning of La Tour’s paintings is not an exaggeration, since clues regarding potential meaning have to be inferred from an examination of the works themselves, their multiple iterations, and related works. However, while his paintings lack the verbal frame of a given title, the choice and depiction of their visual elements prove to be largely determined by verbal considerations—scriptural, allegorical, or proverbial—thus bringing the question of legibility into play at the very heart of the visible.

To learn to read is to light a fire; every syllable that is spelled out is a spark.

VICTOR HUGO

St. Jerome Reading (c. 1624), or St. Jerome (1621–1623; Royal Collection, HM Queen Elizabeth II, Hampton Court; see Plate 15) represents a man holding an eyeglass attentively reading a letter or a document.4 This depiction refers to the faulty nature of human vision, which requires artificial enhancement in order to attain better sight.5 But does this allusion to the ostensible defects of ordinary vision also suggest a reflection on spiritual insight? For seeing better in order to read does not guarantee mental or spiritual understanding. By challenging the immediacy of vision in depicting its mediated character, La Tour invites, through an appeal to reading, a reflection on the difficulty of figuring the invisible realm of faith from the perspective of the visible. In another version of this painting, which is believed to be a contemporary copy after La Tour (c. 1635–1638, Musée du Louvre, Paris), the depicted reading scene is enlarged to include a more complete scenography of reading and writing that combines references to St. Jerome’s biblical translation with his devotional apparatus, namely, the open Bible and the skull.6 The previously mentioned scene of St. Jerome reading a letter is reframed by the presence of the open Bible, which alludes to the sacred in the scene’s otherwise ordinary iconography. This juxtaposition appears to suggest that while the act of reading necessarily entails deciphering letters, there may indeed be a difference in the consumption of secular and sacred texts. The deliberate juxtaposition of the letter with the sacred book, along with the glasses, constitutes an allusion to the double nature of reading as understood in its ordinary and also allegorical sense: a reading according to the letter and a reading according to the spirit.7 In yet another painting of St. Jerome reading (attributed to La Tour’s workshop, Musée Historique Lorrain, Nancy), the depiction of the candle illuminating the letter from behind renders it incandescent.8 According to Francine Roze, this illuminated letter is of possible papal origins and concerns discussions regarding the translation of difficult biblical passages.9 But does the translation in question have spiritual implications as well? The transparency of the letter’s illuminated vellum and its affinity with “the sheen of the oil paper of a lantern” give, according to Choné, “a new, unexpected, immediately spiritualized image of ‘hidden light.’ ”10 Figuring the image of Christ as only accessible to us “like the light in a lantern,” the depiction of these translucent pages evokes the illuminating power of the biblical word in fostering enlightenment.

La Tour’s repeated depictions of St. Jerome reflect the saint’s rising importance during the Catholic Reformation not just as a penitential figure but also as a translator of the Bible, the Vulgate, which was sanctioned by the Council of Trent as the authentic and authoritative Latin text of the Catholic Church.11 The question arises whether La Tour’s repeated focus on representing St. Jerome as a reader and a translator is a way to figure his own dilemma as a painter struggling to “translate” in a visual mode the ineffable effects of spiritual illumination inspired by the divine word. As noted in Chapter 1, St. Jerome bitterly reproached himself and practiced self-mortification for his sin as a reader in having taken too much delight in the pagan word. His gesture points to a fundamental danger in the act of reading and translation: that of taking pleasure in words for their own sake rather than for the sake of God. The representation of St. Jerome as translator of the divine word is haunted by the secular seduction of his rhetorical training, which he undertook to perfect the art of speaking. By focusing on St. Jerome’s infraction and penitential deed, La Tour drew attention to the fundamental ambiguity shadowing all acts of reading, since its delights hold out temptations that may lure the reader’s attention away from godly books to pagan ones. But does this penitential display of St. Jerome’s secular delight in words and verbal expression stand in as a figure for La Tour’s dilemma as a religious painter?

To answer this question, we turn to St. Augustine’s discussion of the pivotal role played by reading in his Confessions, in order to elucidate its meanings and its transformative (or, rather, transfigurative) powers in bringing about his conversion. Commenting on St. Augustine’s reception during the Renaissance, Meredith J. Gill remarks that “this was a conversion in which Augustine surrendered his will to God’s by means of a book. It was words—hearing and reading—that effected his conversion.”12 St. Augustine first discovers the importance of reading when he witnesses Ambrose’s engrossment in his quiet moments of reading: “When he read, his eyes scanned the page and his heart explored the meaning, but his voice was silent and his tongue was still.”13 Augustine clearly found Ambrose’s silent manner of reading unusual, since reading in Augustine’s time was ordinarily performed out loud.14 Present to the other’s gaze but absent to his or her look, the silence of reading creates an introspective space that eludes the grasp of the beholder. Visually inaccessible yet physically palpable, the experience of reading emerges on the order of an enigma, a mystery whose private nature resists public scrutiny. Marking the transition from orality to literacy, the reader Ambrose withholds his voice from lending audible, public semblance to sacred text, muting its speech into an inaudible whisper whose echoes attest to movements of the heart.15

Not only does St. Ambrose’s silent reading serve as a consummate embodiment of his faith, but it also prefigures the importance of reading in effectuating Augustine’s conversion. In the eighth book of the Confessions, Augustine’s spiritual crisis, described as “dying a death that would bring me to life,” leads him to take refuge in a garden to escape the torments and divisions in his inner self. There he overhears the clarion-like echoes of the singsong voice of a child’s repeated refrain, “Take it and Read, Take it and Read.” This call (or rather command) leads him to retrace his steps back into the house and pick up (or rather seize) St. Paul’s epistles, to “read the first passage on which my eyes should fall.” As he marks the place with his finger, he feels the “light of confidence” flooding his heart. This account serves as an extraordinary attestation to the power of reading to effect not just a transformation but a conversion—the transfiguration of Augustine’s heart through spiritual illumination. Reading thus brings about conversion, enabling its articulation as an event that does not explain but merely marks a point of departure for comprehension, as Louis Marin has noted: “The event articulates; it doesn’t explain, it makes possible an intelligibility: comprehension’s point of departure, the event is just as much the blind task, it is not itself comprehended in the narrative that takes its meaning from it.”16 However, while radically disrupting the continuum of Augustine’s life, the intervention of this conversionary event reflects not just this particular scene of reading but echoes several other conversion scenes triggered by reading, notably modeled by Victorinus, Ponticianus, and Anthony.17 Augustine must witness, either through hearsay or in person, several scenes of reading leading to the conversion of others before his own reading of the sacred text can bring about his own conversion. It will take an “education” of sorts for Augustine to learn how to “read” so that the spirit of the sacred texts can affect him sufficiently profoundly to enable a change of heart. Thus the apparently unique event of Augustine’s conversion emerges out of a structure of iterated readings, an echography of enunciations whose repetition enables the eruption of the sacred—the advent of annunciation from enunciation.

This idea of reading as an act that both prefigures and accomplishes spiritual illumination can be found in The Education of the Virgin (1650, Frick Collection, New York; see Plate 16), attributed to La Tour and/or his son Étienne de La Tour. The scene depicts the Virgin as a child being taught by her mother, Anne (later St. Anne), to read.18 However, apart from its title, which was added almost three centuries later, this reading scene at first sight lacks indices to indicate its sacred status. What in particular allows the observer to conceive in this representation, which at first seems quite ordinary and familiar—a mother teaching her daughter to read—the insignia of the sacred? In this context, it should be noted that Pariset identified in La Tour’s painting significant departures from the conventions of traditional religious iconography; the painter did not include the signs traditionally associated with sainthood in his representation of religious scenes: “Like Zurbaran, La Tour knows the iconographic rules, but he suppresses the saints’ halos and the angels’ wings.”19 The deliberate suppression of sacred indices and the exaggerated simplicity of décor, costume, and light impart a quasi-religious aspect to this scene, marking the ambiguity of the representation of the sacred and the profane in La Tour’s devotional painting.

Several essential traits of La Tour’s paintings should be considered in order to elucidate the transition from the profane to the sacred: The child is presented in profile. The whitish tint of her illuminated face juxtaposes its paleness with the book parchment illuminated by the candle. Representing a face seen only from one side (like a single page), a profile shows us but one aspect of the figure; the rest is hidden by this very posture. The outline of its lateral border alludes to this hidden dimension, inscribing the invisible in the visible order of the image. Drawing on the ability of the profile to designate a double reality, this liminal representation of the child’s face delineates the potential inscription of the sacred into the prosaic reality of her daily life. In one hand, she holds a candle illuminating the scene; her other hand eclipses and nearly blocks the flame, rendering her hand translucent. The mother cradles and holds out the book like an extension of her voluminous body, and her serene gaze overlooks the scene. Here in its appeal to volume and claim to presence as pure surface the maternal body acquires an exaggerated dimension, “an idol’s size” (according to Quignard), a trait André Malraux more generally attributed to La Tour’s painterly style: “His ‘secret’ was that of rendering in a seemingly naturalistic portrayal, certain volumes as though they were surfaces: in flat planes.”20 Alongside the mother, a wicker basket, doubled by the projection of its shadow on the wall, completes the peacefulness of this domestic vision.

The young girl is shown looking at the book’s open pages, which open like the sides of a cross and span the breadth of her mother’s lower body. While inviting the spectator’s gaze, this invitation to look is thwarted by the open pages, which act as a visual lure. Their look merely suggests the visual appearance of letters on the page, amounting to illegibility, which is akin to blindness. This implied interrogation of the “look” in its ability to “see” in the act of reading is contrasted with the workings of the look in visual and pictorial terms. The latter is depicted through the display of a wicker basket to the left of the book, shown both as physical object and as a representation on the wall. However, this staging of the look through the doubling of the basket by its shadow image reveals its deceptive qualities, along with figuring painting’s duplicative power as an art of shadows. The crisscross pattern of the basket’s weave creates a visual counterpart to the words weaving across the pages of the open book, suggesting the possibility of another kind of seeing. Its reiterative logic emerges from the pattern of crossing textures rather than image. This crisscross pattern is insistently repeated in the mother’s and daughter’s woven belts, inscribing, through texture, subliminal allusions to the cross and thus the painting’s spiritual connotations. Remaining closer to the iterative aspects of enunciation than to the punctual logic of the image, these visual repetitions evoke the “illuminating” power of biblical speech while also suggesting a reappraisal of the duplicative powers of painting.21

Following this reiterative logic, let us now retrace our steps in order to analyze certain significant details. First, the question arises as to why the child Mary is depicted as learning how to read. According to Manguel, “learning to read is something of an initiation” because it represents a ritualized passage from infancy to adulthood achieved through instruction.22 This motif of reading is clearly of great importance in Christian iconography from the Middle Ages onward and constitutes a key element of the iconography of the Annunciation and thus of Christ’s incarnation. The angel Gabriel is often shown as having surprised Mary in the act of reading. For the art historian Daniel Arasse, “ ‘the scene’ of annunciation is nothing but an act of enunciation,” which refers to its meaning being constituted purely through the verbal exchanges between Gabriel and the Virgin, which mark the incarnation of the Word become flesh.23 The representation of the child’s profile refers to her symbolic status as bearer of the divine word, and it reprises the disposition of the angel Gabriel (who is typically shown in profile) in the Annunciation, who acts as the messenger of the divine.24 This structural overlap of Gabriel’s and Mary’s positions leads one to ask whether the child Mary is, in effect, the bearer of a message she has not yet learned how to read or to understand.

A closer examination of Mary’s hands hints at her ambiguous status as both messenger and message and at the necessity of her education, which, as will be revealed, is not simply learning to read letters but about the attainment of spiritual illumination. In her left hand, she holds a wax candle illuminating the scene, her ring finger and little finger are rigidly extended to point in a gesture of demonstration designating the pages of the open book, and her right hand covers the flame, blocking it almost entirely.25 This gesture renders her hand translucent in a pose simultaneously ordinary and mysterious, reminiscent of the iconography of the saints accompanying the declaration of miracles and revelations.26 The candle, an everyday source of light meant to facilitate reading, is eclipsed, first by the child’s hand, then by the illuminated book that is designated by Mary’s pointing fingers as the bearer of true illumination. Mary’s three gestures—as bearing the candle (and thus the illumination), as designating the book (and thus the figuration of the sacred), and as messenger announcing a miracle or a revelation—outline a spiritual journey wherein the messenger and the message are conflated in a play of visual and verbal echoes.

What book is the child Mary, who is quite young, reading? Presumably the text in question is the Bible, thus making the beholder wonder whether Mary is reading a text that prefigures her own coming and the advent of the Lord. However, at this point in her life, this child’s reading will not provide sufficient illumination, for she will remain innocent and ignorant of its message. To attain spiritual illumination, it will be necessary to await another scene of reading, that of the Annunciation, which will then reveal her sacred destiny. To clarify this point, it is helpful to take a quick look at The Annunciation of Duccio di Buoninsegna (1508–1511, National Gallery, London), which depicts the Virgin surprised while reading the book of Isaiah (7:14): “Behold, a virgin shall conceive and bring forth a son” (ecce concipies in utero, et paries filium). This passage is legible in Latin in her book, which faces the beholder.27 Echoing the Old Testament’s prophecies, unintelligible until then, this painted citation manifests their meaning as enunciations in the aftermath of the Annunciation. The greetings and words of the angel Gabriel elucidate the prophetic language of the Old Testament, which designated the Virgin as the predestined receptacle of the divine word. It is therefore significant to note in La Tour’s Education of the Virgin an almost imperceptible detail in the representation of the book, which is presumed to be the Bible. The text shown on the left page begins in the center of the page, indicating a new chapter beginning, a commencement that can also mark an end. Perhaps this is an allusion to Mary as figure of origination and matrix of enunciation: an allegory as both the mother and the book, in line with Luke’s confirmation that Mary “conserved all words [sayings] in her” (Luke 2:19).28

In effect, Mary’s reading raises fundamental questions, ones that underlie all reading, for the problem does not consist merely in determining what she is reading. What is at issue here is much more complicated. It concerns the time of reading, and it asks: To what time does reading belong? In The Education of the Virgin, the representation of the biblical past is assimilated into the present of a stylized reading scene that simultaneously evokes the ambience of the seventeenth century. For Scholes, this image represents a veritable “allegory of reading” by assimilating the past into the present and by offering us a visualized version of what we are doing when we read.29 This assimilation of the past into the present gives this image its devotional force: the power not only to access a past truth but also to convince its beholder by establishing this truth in the present of the act of reading. In this way, the staging of this image makes visible the fundamental ambiguity of reading, which implies and plays on several temporalities at the same time. The young Mary, the supposed reader of the Bible, reads the words of Isaiah, which belong to the biblical past but which, as prophecy, also open to a future preordained by its enunciation. However, for these words to be experienced and assumed, it would be necessary that the young reader recognize herself as this message’s addressee. Instead of penetrating the text, Mary, the reader, must allow herself to open like a book so that the biblical truth can be announced and become intelligible.30 This recognition comes about belatedly in the aftermath of the angelic visit: Mary will be illuminated by the angel’s greeting, Ave, already echoed in Isaiah’s words. The “radiance” of these pronouncements will enable her to recognize herself as “handmaiden of the Lord.” Thus, The Education of the Virgin represents an apprenticeship in reading as an affair of letters wherein the spiritual dimension and its opening onto the sacred remain yet to come.

Discussing the increased attention paid to the details and textures of materials and clothing in pictorial images of late medieval spirituality, the art historian Alexander Nagel argues that such depictions should not be seen “in opposition to spiritual ends, but in tandem to spiritual practice”: “The theology of incarnation drove an intensified interest in the visualization of Christ’s early life in late medieval spirituality, and prompted the development of techniques to coordinate those temporal references with the circumstances of devotion.”31 Rather than interpret clothing merely as a signpost of temporal change, he proposed a consideration of the role that these temporal references may play in furthering devotion. A closer look at André Félibien’s Entretiens sur les vies et les ouvrages des plus excellens peintres anciens et modernes provides a seventeenth-century French perspective on the nature and appropriateness of clothing.32 In addition to recognizing clothes as markers of temporal and national differences, which instruct beholders through the representation of particular historical moments, customs, and fashions, Félibien also insisted on the importance of appropriate clothing in sacred settings. He emphasized the notion that depictions of clothing must be in accord with the time, place, and figures represented and must not clash with or subvert the painting’s religious aims.33

The idea of considering the role of clothing in fostering devotion is particularly pertinent to an examination of La Tour’s paintings, especially The Education of the Virgin, both because of the artist’s unflinching focus on the human figure and because other visual details that would enable the viewer to ascertain the temporality of the image are lacking. In La Tour’s devotional works, the emphatic simplicity of clothing, its lack of adornment, and its basic color scheme (whites, red, browns, and sometimes grays) attest to a deliberate pictorial attempt to restrict and manage its representation. Compared to the plethora of concrete details used to convey abject poverty in depictions of peasants in works by contemporaries such as the brothers Le Nain, La Tour’s representations of ordinary folk in his nocturnes present highly schematized and abstract renditions of sartorial choices. Clothes are divested of the social significance they present in his daylight paintings and are imbued with a visual simplicity and majesty suggesting that their meaning may have other connotations, ones of a temporal and spiritual order. So, if the meaning assigned to clothes is not restricted to their visual appearance or exhausted by their social functions, what other significations do they have? Can clothes facilitate, through their implied temporal connotations, the experience of devotion? But to what end? Is it to bring the viewer closer to the painting by showing ordinary people in ordinary dress engaged in common activities? Or is it an attempt to render the biblical past alive by bringing it into a present associated with La Tour’s own time?34

The French word for clothes (habits) comes from the Latin habitus, which signifies a manner of being. Another term for clothing (vêtement in French) derives from the Latin vestimentum, which means an outer garment or a robe used to cover, hide, protect, or decorate the human body. However, the putting on or taking off of clothes has personal and also social and religious implications, such as we see in the distinction between everyday clothes and ceremonial garments. Vestment and divestment function as signs of ritual and institutional passage, as implied in the French expression prendre l’habit, which means to become a priest or monk, referring to the ceremonial assumption of clothing indicating entry into a religion and its institutional orders. The verbal expression for the assumption of a particular mode of dress establishes a relation between outer garments and secular or religious manners of being. Indeed, clothes may also serve to figure the calling of faith, marking through external signs the outcome of an inner transformation, as evoked in St. Paul’s pronouncement: “You have put off the old nature with its practices and you have put on a new nature, which is being renewed in knowledge after the image of its creator” (Col. 3:9–10). A change of heart that privileges the spiritual over the material leads to a new way of dressing, figuring both a change of conviction and the assumption of a new position in the world.

This latter spiritual import of clothing is the focus of discussion here insofar as it enables the conflation of multiple temporal references within an image. La Tour’s pared-down rendition of clothing not only figures the past or the present but also serves to foreshadow the future by evoking a biblical past bearing the sign of a time to come, understood as the advent of a new faith and new mode of being. La Tour’s representation of clothing reprises the temporal paradoxes associated with the biblical story, which according to the art historian Georges Didi-Huberman is “less the account of events carrying their meaning within them than a prefiguration of what ought to follow them: the ‘shadow of the future’ in Augustine’s words.”35 Eschewing visual expectations, La Tour’s stylized and abstracted account of clothing relies on references evoking the biblical past in order to inscribe the latency of a future still to come.36 This inscription of temporality in the image mandates the intervention of visual exegesis founded on scriptural exegesis.

The temporality of devotion, like that of the scriptural verbum, partakes of all times, referencing simultaneously the past, present, and future. The immediacy of the present is conflated with references to the Old Testament in order to foreshadow the New Testament, whose advent will take the form of an overshadowing commanding spiritual servitude and devotion. The representation of clothing acts as a gateway enabling the viewer to pivot between different times and spaces. This stylized dress evoking the manner and demeanor of ordinary people—peasants, servants, and maids—serves to point in two opposing directions: back toward biblical origins and forward to a time to come figured in the Gospel. In The Education of the Virgin, these temporal references are brought together in the fiction of a present embodied in the presence of the beholder. The stylistic simplification and abstraction of the clothes enable a rapprochement between the secular reality of seventeenth-century Lorraine and the beholder. This rapprochement functions as a vehicle for gaining proximity to the incarnations of the sacred in an agrarian world as represented in both the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament. La Tour’s stylized depictions of clothing rely on the intervention of the beholder to activate their symbolic potential. They mobilize the beholder by enabling movement between different times, since the ordinariness of the secular present becomes the gateway to the sacred past, which also figures the advent of the future.

The representation of reading in La Tour’s paintings also serves to figure the spiritual dilemma concerning the difficulty of being receptive to the illumination of the sacred. Given the weight of ordinary existence and its prosaic character, how does the sacred manifest itself, and how does one recognize it? This quest for illumination and spiritual knowledge in the face of doubt is powerfully sketched in another nocturne, The Dream of St. Joseph, or St. Joseph’s Dream (c. 1635–1640; Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nantes; see Plate 17). Resembling The Education of the Virgin, this work at first sight presents a scene that is both quite ordinary and deeply mysterious. Joseph’s dream and his visitation by an angel were preceded by a moment of profound doubt, when Joseph learned that Mary was expecting a child and wondered about their fate. Responding to his doubt, an angel appeared to him in a dream, telling him to marry Mary and name the child to be born Jesus (Matt. 1:20–24). Joseph’s visitation by an angel recalls other scenes of angelic visitation, such as the Annunciation, except that unlike Mary, Joseph is no longer reading, having fallen asleep with his book in his hands. In his dream, he encounters the angel, thus crossing the boundary separating the profane from the sacred. Commenting on dreams, Pavel Florensky noted their liminal status in marking the passage between the visible and the invisible: “And so dreams are the images that separate the visible world from the invisible—and at the same time join them. . . . The dream is the common limit . . . the boundary where the final determinations of earth meet the increasing densifications of heaven.”37 Attesting to moments when consciousness hugs the boundary of the crossing, the dream acts as a gateway to the movement between the earth and heavenly realms.

At what point and how does this depiction of a child, seeking to awaken an old man who fell asleep while reading (as attested to by the presence of the candlesnuffer close at hand) shift from the realm of worldly appearances to that of an angelic apparition in Joseph’s dream? Are we as beholders witness to the dreamer or to the dream? Blind to being seen or nearly touched, Joseph, the reader, dwells in the penumbra of his dream.38 However, certain details hold our attention and help us clarify the nature of this scene, now to be understood as that of an angelic apparition. The child’s illuminated belt, made of golden threads (whose sheen indicates the virtuosity of the painter), serves, according to Jean-Claude Le Floch, “as an act of contrition for having sacrificed the traditional angels’ wings.”39 The presence of the candlesnuffer and its shadow on the table foregrounds the absence of a shadow of the angel child’s hand on the old man’s chest. While alluding to the virtuosity of both the painter and the painting, these details also confirm an angelic apparition whose spiritual aspect precludes the logic of the visible.

Considering that the angel appears to Joseph three times in three different dreams, the question is to determine, if possible, which dream is being depicted here. An examination of these three occurrences of angelic apparition reveals that only the first apparition responds to an important spiritual crisis. This crisis is preceded by a profound moment of doubt in which Joseph learns that Mary is expecting a child whose origin is in question. Joseph’s doubt, which implies Mary’s possible repudiation, finds in the angel’s words both relief and response. The register of the first angelic discourse is on the order of persuasion; the other two occurrences take on the form of orders. The angel appears to Joseph to order him to rise and flee with his family to Egypt (Matt. 2:13). He then comes back to command Joseph to rise and return with the child and mother to Israel (Matt. 2:19–20). The textual indices suggest an allusion to the first dream, a supposition that must be examined at the level of its visual evidence. Comparing this image with others of the same genre by Philippe de Champaigne and Simon Vouet, Pariset noted the singular presence of the open book in La Tour: “Did he want to indicate that Joseph meditated on the passages announcing the Messiah and the mystery of the Incarnation? Doubtless, and all of a sudden, there are new reflections foreign to all the artists who have dealt with the theme.”40 Thus the open book Joseph holds in his hands is revealed to be a key detail that bears witness to the presence of both a spiritual crisis and its resolution manifested by the sacred vision of the angelic apparition.

The illumination of the child’s or angel’s face from a candle outlines in extraordinary detail an ear and the open mouth, poised in an act of speech. The expressive qualities of this speech are emphasized by the illumination of the underside of the slightly curled left hand pointing in an oratorical gesture. The generous sweep of the right-hand sleeve eclipses the candle, leaving visible only the tremulous tip of the flame. This concentrates the candle’s radiance onto the end of the pointing finger of the right hand, backlit in beads of light (see Figure 3). This point suggests, without actually depicting, the painting’s sacred or “angelic conceit” and constitutes its pictorial punctum.41 The pointing finger emerges as the painting’s transformative fulcrum, where the visible semblance of the child dissolves into angelic apparition and where sight is overwhelmed by spiritual insight. This effect is obtained through a gesture whose reach simultaneously evokes an expressive gesture used to foreground discourse and a hieratic gesture, whose priestly connotations reference the sacred. Inspired by scripture, the hieratic gesture serves to clarify the advent of a spiritual insight that escapes the grasp of the visible.42 Jacques Thuillier has commented on La Tour’s unique approach, which demonstrates his rejection of traditional indicators typically used to designate this episode. The essential lies in the depiction of an inward experience, an encounter with the sacred in the form of a celestial apparition, “at the very moment when, exhausted by his struggle to understand the spiritual truths of the Spirit, he relapses into his torpor. It is the unforeseeable gift that so preoccupied the entire seventeenth century: the mystery of grace.”43 Virtually inscribed in the image, the possibility of Joseph’s spiritual transfiguration through the unforeseeable gift of grace dramatizes his momentous encounter with the sacred.

Figure 3. Detail of a pointing hand from Georges de La Tour, The Dream of St. Joseph, c. 1635–1640, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nantes.

The interface of the visible and the legible in La Tour’s works is brought into precise focus in La Tour’s The Discovery of St. Alexis, also known as The Discovery of the Body of St. Alexis (c. 1645–1648, Musée Historique Lorrain, Nancy; see Plate 18).44 According to Greek legends, Alexis was the son of a Roman patrician named Euphemianus. On the night of his marriage, he secretly left his father’s house for the Syrian Orient, where he lived chastely and practiced his faith as a pious ascetic. After seventeen years, he forsook the growing fame of his sanctity and returned to his father’s palace. For another seventeen years, he dwelled as a beggar under the palace stairs, unrecognized by his father, wife, or attendants. After his death, a piece of paper identifying him (based on a divine command, according to Voragine) was found in his hands. La Tour’s painting depicts the moment when Alexis’s body is found, a discovery whose true meaning emerges only through the reading of the note.45 This nocturne depicts a young page bending over a man’s body and holding a torch in one hand to illuminate the man’s face while gently pulling away the cloak to reveal his features. Absorbed in visual scrutiny, the page attempts to discover the man’s identity. But this appeal to the power of vision is destined to failure, since Alexis had lived in plain sight in his father’s house without being recognized. Marking the paradox of having dwelled in full sight yet not having been seen, deceased Alexis still clutches in his hand the paper that will cast true light on his identity. It is only upon reading the note that his father, wife, and former servants are able to recognize Alexis and thus grieve for him. And this grief is now imbued with the mute reproach of not only his loss but also the failure of having failed to recognize him while he was still alive, leading his wife to exclaim: “Now begins the grieving that has no end.”46 This radical misrecognition, this inability to see beyond ordinary appearances, which was inadvertently perpetrated by those who loved him most, serves to underline the spiritual nature of St. Alexis’s faith.

The drama of St. Alexis’s posthumous recognition tangibly evokes the interface of the visible and the legible in La Tour’s works. Resolutely yet delicately painted by utilizing a rich tonal range of reds, golds, and the azure blue of Alexis’s tunic (an allusion to his sanctity), this work systematically stages, through the display of light, the blindness at the heart of vision. The seduction of the visible, that is, of the promise and lure of knowledge contained by sight, is contrasted with the illumination of the word, whose reading relies on sight to provide insight. The page’s compulsion to look in order to know is contrasted with the look of reading, a look that has to be learned in order to be able to see anything at all. The reading of the note makes possible the identification of Alexis and also illuminates his existence by casting all his prior actions in a saintly light. What his family and attendants now see in Alexis is not just the man but his unimaginable sacrifice in the name of faith, which will sanctify his life as St. Alexis. In this way, reading recasts the event of the discovery of Alexis’s body by intimating the presence of the sacred. All the ordinary-seeming details of the painting become illuminated and legible as a function of spiritual insight. By positing true knowledge on the side of the word rather than on the side of sight, La Tour privileged spiritual contemplation, the radiance of which will not be eclipsed even during the darkest night.

La Tour’s pictorial approach recasts seeing in the mode of legibility, or reading, a strategy that brings the beholder’s contribution into the picture. Privileging reading over merely seeing, La Tour drew on motifs and iconographical details of the incarnation in order to probe painting’s spiritual potential. Indeed, it seems that he redefined seeing itself as a kind of specialized reading, where visual details cease to matter in their own right, serving to expand the visionary space of insight or devotional contemplation. Reading becomes a figure for spiritual contemplation because it opens up a virtual space within the visible world that is visionary rather than visual in character. La Tour applied to the visual details of painting an exegetical approach based on reading that treated a biblical story as “less a surface than a threshold to be crossed in order to enter scripture.”47 He reprised in the visual domain an understanding of the biblical story as a threshold whose crossing enables the viewer to go beyond the literal meaning in order to enrich the signifying potential of what is seen in terms of deeper levels of spiritual meaning.48 Biblical stories cannot be exhausted by simple accounts of events because they bear latent meanings whose significance becomes recognized only belatedly as prophecies wherein enactment elevates and transfigures the spirit. Such adaptation of a scriptural approach to painting requires the mental activation and intervention of the viewer in order to facilitate the passage and transformation of the profane into the sacred.

But what about La Tour the painter? What kind of secular meditation on the nature of painting does La Tour’s radical decentering of vision and of the beholder imply? Challenging the hegemony of vision and the visible, La Tour’s devotional works test the representational limits of painting as a visual medium. Maurice Merleau-Ponty notes in The Phenomenology of Perception that “it is possible to speak about speech whereas it is impossible to paint about painting.”49 However, by interrogating the visual and representational conceits that define it as a medium, La Tour’s paintings depict, through the betrayal of painting, its conditions of possibility. Appealing to the legible, his devotional paintings cast into doubt the knowledge represented by vision in its reliance on visual signs. La Tour’s paintings do not simply give themselves to be seen but also to be read in order to be fully experienced and understood. His works show that what the eye discovers in its attempts to understand what it sees is mediated by the illuminating power of the Word. Like the books inviting to be read La Tour repeatedly depicts, his paintings are revealed not solely as objects of representation but also as instruments of insight. Their allegorical character demands to be deciphered, decoded, and read rather than merely seen. Through the deliberate juxtaposition of visual and legible concerns, his paintings demonstrate how the figurations of faith as spiritual illumination compete with and challenge the meanings attached to the visual realm of painterly expression. By bringing legibility into play, La Tour’s devotional paintings emerge today as profound meditations on the limits of painting as a medium that abides in the visible. By revealing the layer of the invisible that lines the primacy of vision and the visible, his works succeed in the difficult if not altogether impossible task of challenging and dismantling what Herman Parret described as “this hypostasis of vision in our culture.”50