We’re blind to what we don’t expect.—Professor Ellen Langer

Even if none of the research mentioned in the previous chapter had been carried out, most people have an intuitive understanding, based on everyday experience, of the relationship between language and the ‘gut response’. Think of how you feel when the boy racer on the freeway cuts you off in the fast lane, then winds down the window and yells obscenities at you. Or remember a heated argument with a spouse or a friend, or being reprimanded by your boss.

These are just words—except they have the power to light up the brain and set in motion a complex chain of neurochemical events, causing your palms to sweat and your gut to wrench, and which now have to be metabolized before your body can return to its default ‘normal’ state.

One of the concerns which the phenomenon opens up involves the possibility of negative and unintentional priming by means of the increasing number of patient questionnaires being introduced to ‘assess’ a wide variety of conditions, including pain, depression, anxiety, and obsessive compulsive disorder.

As we reported in the previous chapter, Davidson’s team elicited an asthma attack with a single condition-specific word. What is happening inside the patient who is required to work his way through anything from 10 to more than 100 words related to illness, discomfort, and pain without being invited to offer his own words to describe his unique experience?

The quality of words is important, too, Richard Bandler often says, ‘Your voice bathes the listener’s entire body with the waveform. What you say and how you say it has a direct impact on the listener’s nervous system.’

Candace Pert’s recent research seems to bear this out. Words (like music), she says, affect the ‘psychosomatic network’ by causing certain ion channels to either open or close, thus regulating how a particular neural network works. ‘You’re literally thinking with your body,’ she adds. ‘The words…because sound is vibrating your receptors…actually (affect) the neural networks forming in your brain.’111

Building resilience

Wherever treatment derived from the molecular, cause-and-effect model has failed to bring the patient relief, we need to look more deeply into what else we can do. Since ‘stress’ is undeniably a factor in all ‘functional’ disorders, we have it within our powers to: reduce sympathetic arousal; help the patient learn to recover allostasis, not by blocking the symptoms of imbalance, but by helping him to raise the bar on his own physical-emotional resilience; and, wherever possible, alter the structure and process of his illness-behavior.

The medium is the word. Our ability as a species to influence and be influenced by language is an important contributory factor to restoring and maintaining health. The fact that we are enormously suggestible can and should be exploited—although, of course, with due and diligent care.

However, there is more. Much more. What researchers now understand is that the tone of someone’s voice, the kind of pictures on the wall, the lay-out of the room, and even the temperature of a mug of coffee he is holding can powerfully influence someone’s response…sometimes nearly at the speed of light.

Aileen sits at the computer console, staring intently at the screen. A senior who regards herself as ‘mildly computer illiterate’, she is slightly nervous to begin with. But the friendly researcher reassures her that all she has to do is to pay attention to the screen as a succession of words and phrases are flashed, faster then she, or anyone else, is able to read.

What she doesn’t know is that all the words that are being presented to her unconscious mind are positive stereotypes about aging. Words and phrases such as, ‘experienced’, ‘wise’, ‘good with children’ are presented rapidly, each image lasting less than one hundredth of a second.

Sitting in the next booth is her friend Betty, almost the same age, with similar interests and in much the same state of health.

Betty’s screen, however, features a stream of negative words and phrases, all related to aging: ‘memory gets worse with age’, ‘aches and pains in the morning’, ‘need glasses to read’. Once again, the speed with which these images are presented prevents them from being read consciously.

Neither Aileen nor Betty know what the experimenters are looking for. But later, they are both given a memory test and a test to gauge their attitude towards aging.

The results are eye-opening, even to the researchers themselves. Aileen, and all the other elderly people involved in her group, demonstrate not only a significantly improved memory, but a markedly more positive attitude towards growing old.

Betty and her cohorts, on the other hand, do consistently worse. Their memory deteriorates, and they are significantly less inclined to regard growing older in a positive light.

Experiments along these lines were conducted by psychologist Becca Levy, who, together with Jeffrey Hausdorff, Rebecca Hencke, and Jeanne Wei, went on to show that presenting individuals with words and images related to health can trigger improved physical and psychological health, as well as healthier behavior. Likewise, words related to retention and recollection activated a healthier memory and increased cognitive abilities.112,113

It is particularly important to note that all of the words and images were presented to the test subjects outside of their conscious awareness. In other words, their physical and emotional states were buffeted by the winds and currents of the words the experimenters used, regardless of the meaning the latter intended to convey. Since the process functioned at an unconscious level, the speaker, not the listener, became responsible for the outcome of the conversation.

We have already discussed verbal (semantic) priming, and mentioned that it can take place outside the listener’s conscious awareness. However, primes can occur in all senses, including sight, touch, taste, and smell.

Primes differ from anchors (discussed later in this book—see pages 145 to 157), in that the latter are simple stimulus-response (S-R) patterns, with one trigger setting off (firing) a specific state or response. Primes, on the other hand, are a function of implicit memory—cues that subliminally tell us what is expected of us: what to feel, how to behave, how to respond. Since they are usually embedded in our psyches during a lifetime of unconscious experience, they operate silently, consistently, and, all too often, to negative effect.

Harvard’s Ellen J. Langer has demonstrated this phenomenon, elegantly and in many different ways. One study involved getting participants to role-play being air force pilots. A control group went through the same flight simulation as the ‘pilots’, but without any particular preparation. Both groups were asked to read eye charts both before and after the ‘flight’. Since almost everyone knows that one of the conditions for qualifying as a pilot is excellent vision, Langer and her associates predicted that those participants who had been primed by listening to lectures, dressing in uniform, and adopting a ‘pilot mindset’ would show improved vision over those who were simply asked to read the eye chart from the same distance.

This, indeed, is precisely what happened. Simply pretending to be a pilot brought about a measurable improvement in the subjects’ visual acuity.114

Langer’s colleagues devised another intriguing test of the power of priming.

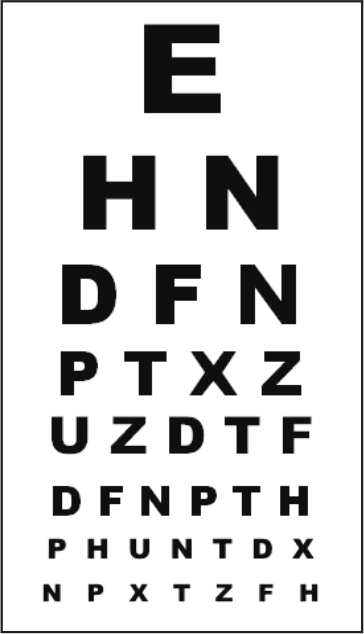

Identify the chart below and take a moment or two to explore the implications of this familiar image.

Most people in the West have had their eyes tested and will have no problem identifying the chart opposite.

However, the implications of this iconic image are profound. Implicit in the design of the chart, and the way eye tests are usually administered, is the assumption that the viewer will have increasing difficulty reading the letters from top to bottom, from larger to smaller. The subject in fact, is being primed to expect that his vision will worsen as he reads on.

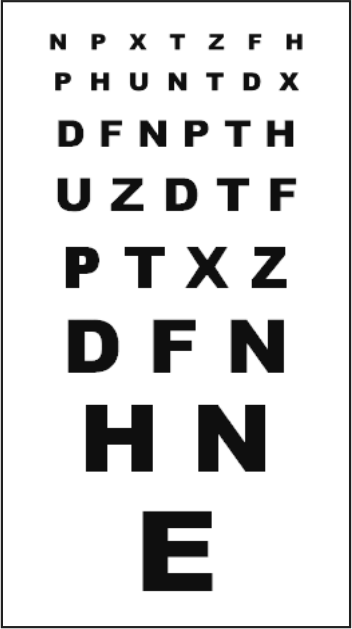

Now, what would happen if the image changed so that the smaller letters were at the top and the larger ones were at the bottom as shown here?

In this case, the expectation is different. The reader starts with the anticipation that his vision will get better as he reads on…and, it does.

Langer notes, ‘Participants tested indeed showed enhanced vision using the redesigned chart, and they were able to read lines they couldn’t see before on a standard eye chart. In all but one case, subjects could read the same number of small letters on a line on the reverse chart that was only visible on a line 10 font sizes larger on the regular eye chart. Also interesting was that the subjects thought they did better on the normal chart. We’re blind to what we don’t expect.’115

Langer’s most intriguing study, of course, is the one central to her book, Counter Clockwise, and repeated in the BBC documentary, The Young Ones. Here, Langer was able to reverse many of the signs and symptoms of aging by simply returning a group of elderly and infirm people to an environment that replicated a time in which they were in their prime. By recalling and ‘re-experiencing’ health and wellbeing, the subjects experienced profound physical and emotional rejuvenation.116

The risk of negative priming

Now, let’s see what happens when you visit your doctor’s office.

Even though some effort might have been made to cheer up the environment, perhaps with a few bright pictures in the waiting room, or a vase or two of flowers, the main components will be implements and images associated with illness and disease.

Stethoscopes and sphygmomanometers jostle with kidney basins, tongue depressors, and syringes. Erudite volumes of diseases from A to Z line the shelves; a plastic skeleton—the ultimate mortality prime—hangs lifelessly in the corner. A poster of a flayed corpse, identifying the major muscle groups, dominates one wall.

Overseeing all this is your physician, smart and crisp in a clean white coat, a member of a profession dedicated to prolonging your time on the planet, but with fewer tools to help you achieve a better quality of life than he would care to admit.

Supposing you present with what the medical profession calls ‘medically unexplained pain’. Of course, ‘pain’ is not a good enough word to explain one of the least understood phenomena in psychophysiology. So your physician gives you a form and invites you to fill it in. Along the top of the page is a scale, usually from 0 to 5, inviting you to rate the level of your pain.

If your ability to self-assess is in doubt, you may, instead, find five icons, ranging from the classic smiley-face to a particularly grouchy one, possibly with a tear spurting out of one eye.

The prime here is visual. For all people who read from left to right, the progression from bright and sunny to down, despondent and distressed means one thing: it’s going to get worse (remember the eye chart experiments?).

Then, you’re presented with a number of words allegedly helping the physician zone in on your particular malady.

These are words like: pulsing; pounding; stabbing; cutting; wrenching; scalding; searing; aching; burning; throbbing; hammering; slicing; sharp; dull…usually 20 or more to choose from.

Similar tables exist for other conditions and dysfunctions, including depression, anxiety, and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Their authors claim such metrics are ‘evidence-based’. In fact, the ‘evidence’ is this: a certain number of patients are invited to choose a word describing their experience of their diagnosed condition. If a large enough number of people diagnosed with, say, rheumatoid arthritis, use the word ‘burning’ to describe their pain, ‘burning’ is considered to be an accurate representation of the experience of all sufferers of rheumatoid arthritis.

This generalization from the few to the many is specious, and endemic in medical research. Very quickly, the developers of such tables, as well as those who use them, forget that the word is not the experience it describes. Nor is there any way that it can be proved that all people who use the word ‘burning’ are actually sharing exactly the same experience. In fact, since part of the pain-message is interpreted by the module of the brain that attributes ‘meaning’ to the experience, we can be reasonably sure they are not. Meaning, almost by definition, is subjective. Nevertheless, diagnoses and treatments—sometimes quite invasive treatments—are based on the belief that all patients share the same experience, and that their experience establishes (proves) the existence of a particular condition.

Understanding means re-experiencing

But the problems run deeper than this. As we mention elsewhere (see pages 67 and 223), someone faced with a list of abstract words such as those found on the assessment tables is required to refer to his or her own experiential ‘database’ in order even to understand the words. To distinguish between ‘throbbing’ and ‘aching’ requires that they activate those neural networks where such experiences are stored and, activation and understanding, to varying degrees, means re-experiencing.117

Given the implications of Langer’s extensive studies, and those of a growing number of independent researchers, it seems inarguable that by simply inviting an individual to review a list of pathological descriptors, the practitioner may be priming the patient to experience an even greater depth and breadth of pain. In fact, everything about the consultation—from the posters on the walls of the reception room, through the smell of disinfectant and the instruments of investigation on the doctor’s desk, to the dependence on technology-based test-results and the use of medical jargon—may be priming the patient to experience a greater degree of discomfort and ill-health than that with which he arrived.

In 2012, the Australian government sought to harness this effect by forcing tobacco companies to market their products in drab, olive-green packages with disturbing images of cancer sufferers, sick babies and diseased limbs.

Within days of the packages going on sale, smokers deluged consumer groups and advice centers, claiming the products had been tampered with in order to affect the taste. The implication was that smoking was no longer as pleasant a pastime as it had been when packages were adorned with colorful designs and text, albeit with smaller, less obtrusive images of the ravages of smoking. On the face of it, this was a victory for the anti-smoking brigade, although whether or not smokers might simply adapt to the ‘new taste’, as they have tended to when switching brands in the past, has yet to be determined.

For those who might doubt this effect, we refer you to the 1996 study by John Bargh and Tanya Chartrand. Assuming that goals and intentions are mental representations, Bargh and Chartrand replicated two well-known experiments, the results of which were well known. However, rather than explicitly delivering the goals, the experimenters primed the participants non-verbally. The results precisely matched those of the original experiments, in which the objectives were explicit, supporting their view that the outcome of a particular exchange can be the same whether the subject is activated unconsciously, or through an act of will.118

We urge the reader also to pay particular attention to both the patient’s use of words related to body temperature, as well as to the ambient temperature of the room.

Recent research has found that subjects with weak social connectedness literally feel colder than their more social peers. They might signal this by using metaphors related to temperature, such as ‘cold’, ‘cool’, ‘chilly’, or ‘frosty’.

Meanwhile, low ambient temperatures may actually deepen feelings of sadness and depression. Conversely, warmth—such as that experienced holding a cup of tea—has been shown significantly to improve the subject’s mood.119,120 A pleasant, warm atmosphere in your office, a cup of tea, or even larding your language with warmth-related words, such as ‘thaw’, ‘heat’, ‘snug’, and ‘melt’ may function as re-orientating primes.

Social psychologists have identified at least seven classes of priming.

- Semantic priming, the most common form, uses words to create meaning that, in turn, influences later thoughts.

- Conceptual priming uses ideas to activate a related response (‘shoe’, for example, may act as a prime for ‘foot’).

- Perceptual priming describes the process whereby a fragment of an image is expanded to complete a more complex picture based on an image seen earlier.

- Associative priming relies on ‘collocation’, the means whereby English words combine in predictable ways: ‘chalk’ and ‘cheese’, ‘bread’ and ‘butter’, ‘distinguished’ and ‘career’. Freudian free association is based on associative priming.

- Non-associative semantic priming links concepts, but less closely than semantic or conceptual priming. ‘Orange’, for example, may act as a non-associative prime for ‘banana’ (both fruit).

- Repetitive priming refers to the way reiteration influences later thinking. Advertising motifs and jingles exploit this effect.

- Masked priming occurs when words or images are presented too rapidly to be recognized consciously. Becca Levy’s experiment, described above, is an example of masked priming.

Important points to remember:

- Priming relies on stimuli that influence future thoughts and actions, even though they may not seem to be connected;

- Priming increases the speed at which the primed subject responds or recognizes the stimulus; and

- Priming can install new thoughts and behaviors, or make old patterns and behaviors more readily accessible, and therefore more likely to be utilized than older, less available, material.

EXERCISES

1. Look at the seven classes of priming above. Choose any four. For each chosen class of prime, write down a list of nine overtly positive priming words in context of your own work (for example, 12 words that prime for comfort or relax or heal).

2. Take a close look at your working environment or office. Look at every picture, object, icon, etc. How many are actually sending priming signals? Are they positive or negative primes?

3. Now go back to your lists from 1 above. How can you make these into, subtle covert primes that can be used in your own office or consulting room?

4. Go online and search for images representing the themes of your positive priming words. These can be used in a digital photo-frame placed obliquely to your patient, but within his peripheral vision. Set the images to change about once every three seconds.

Notes

111. Pert C (2006) Everything You Need to Know to Feel Good. Carlsbad, CA: Hay House.

112. Levy BR (1996) Improving memory in old age through implicit self-stereotyping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 71(6): 1092–107.

113. Levy BR, Hausdorff JM, Hencke R, Wei JY (2000) Reducing cardiovascular stress with positive self-stereotypes of ageing. Journal of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 55: 205–13.

114. Langer E, Dillon M, Kurtz R, Katz M (1998) Believing is Seeing. Harvard University, Department of Psychology.

115. Langer E (2009) Counter Clockwise Mindful Health and the Power of Possibility. New York: Ballantine Books.

116. Ibid.

117. Reisberg D (2007) Cognition: Exploring the Science of the Mind, pp 255, 517.

118. Chartrand TL, Bargh JA (1996) Automatic activation of impression formation and memorization goals: Non-conscious goal priming reproduces effects of explicit task instructions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 71(3): 464-478.

119. Social exclusion may make you feel cold. HealthNewsTrack, September 17, 2008, sourced from Association for Psychological Science – http://www.healthnewstrack.com/health-news-668.html

120. Bargh JA, Shalev Idit (2012) The Substitutability of Physical and Social Warmth in Daily Life. Emotion 12(1): 154–162.