When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves.—Viktor E. Frankl204

If you’ve come this far and are prepared to entertain the possibility that people have internal maps of reality that are different from your own, congratulations.

If you’ve come this far and feel it is possible to recognize that your own map may be neither better nor worse—just different—and are prepared to co-create a new cartography, you have broken through one of the most impermeable barriers we know. This is the one that separates ‘right us’ from ‘wrong them’, the attitude that drives the delusion of superiority characteristic of the worst excesses of scientism, religion, and politics. Once breached, this shift has the potential to change ourselves and the world around us in ways almost beyond comprehension.

For, as a species, we create maps, and then ally ourselves with those whose maps correspond most closely to our own. Logic has little to do with it.205 Our willingness to act for those who comply, and to ostracize or punish those who do not, often depends on power granted by some external ‘authority’, whether it is those who pay us, who control the statistics, prescribe the drugs, or promise us eternal life.

Our intention in this book is not to overturn a ‘paradigm’, discard scientific method, or introduce yet another ‘alternative’ medicine. It is to suggest that we learn to relate to, and work with, the uniqueness of the individual in front of us, in terms of her model, and not just to impose our own. Contrary to some opinion, we do recommend following scientific method. We urge practitioners to work systematically: gathering data, forming a testable hypothesis, testing, and then altering it, if necessary. The difference is that we apply it to each person who consults us rather than relying exclusively on the theology of statistical ‘proof’.

In this chapter, we will introduce several algorithms (step-wise approaches) for change. These are not to be confused with recipes or prescriptions. They are intended to provide a framework within which you can explore more creative, big-picture, whole brain approaches. If we are careful to avoid premature cognitive commitment, Medical NLP’s synthesis of algorithmic and heuristic thinking (nothing more than using ‘both sides’ of the brain, text and context) can lead to creative and effective outcomes that match the patient’s unique needs. This can only come from exploring and respecting the patient’s map.

Even some neuro-linguistic programmers advocate or claim ‘acuity’ when, in practice, they are prescriptively imposing techniques on to their subjects with little consideration for, or understanding of, the subjects’ uniqueness.

The ability to think heuristically and algorithmically, to be mindful of rules but not bound by them, is similar to what Ellen Langer has called ‘mindfulness’.206 In incorporating this approach into your practice, we anticipate that you will find newer and, we hope, even better ways of becoming ‘the difference that makes a difference’.

In this chapter, we will broaden our understanding and application of several core principles of NLP in order to integrate them into Medical NLP’s three major algorithms for change.

1. The power of association and dissociation

The word ‘dissociation’—like all nominalizations—is apt to cause problems. To many psychiatrists, it is a symptom of an often severe personality disorder, a breakdown of another nominalization, the ‘ego boundary’.

To hypnotherapists, it describes the characteristic trance phenomenon of ‘watching the self’ thinking or carrying out suggestions.

To practitioners of NLP, it is a deliberately induced state of ‘stepping out’ of an experience or memory and observing oneself from a bystander’s point of view (Perceptual Position 3), usually resulting in a reduction in the intensity of an experience. We have noted earlier that the patient’s attempt to ‘separate from’, to not-have, her problem serves to keep in place a self-perpetuating causal loop.

Negation can be represented linguistically, but not to our essentially non-linguistic right cortex.

The more we try to not-have a symptom, thought, or experience, the more the symptom or behavior persists (whatever you do right at this moment, don’t think of the color blue). Since the patient’s attempt at dissociation is unsuccessful, he is tacitly seeking the practitioner’s collusion in exorcizing her negative kinesthetics.

Much biomedicine is organized in precisely this way: to attempt to remove, chemically or surgically, the ‘bad’ experience. The belief that medicine can—and should—somehow provide freedom from the ups and downs of life is pervasive.

Increasingly, disappointments, losses, frustrations, and challenges present themselves for medical solutions, fuelled by the promises of ‘cures’ and ‘breakthroughs’ by the media and the pharmaceutical industry. This medicalization of everyday living has given rise to what Frank Furedi has dubbed the ‘therapy culture’, which routinely defines people facing challenges as ‘vulnerable’, ‘at risk’, ‘emotionally scarred’, or ‘damaged’.207

The purpose of incorporating the principles and techniques presented in this book into the consultation process is not to ‘fix’ or ‘cure’ those who are faced with non-acute and non-organic problems. Instead, we seek to help them develop new skills to cope and grow from their experience.

The cliché that draws a distinction between temporarily helping a starving man by giving him a fish, or permanently resourcing him by teaching him how to fish, is apposite here. The word ‘doctor’ derives from the Latin verb docere, to teach. Teachers educate, and ‘education’, in turn, originally meant ‘to lead out’. Ideally, the process of ‘healing’, should, at least in part, involve helping the patient to access, develop, and draw out her own resources in order to be able to respond to those challenges, physical and emotional, that are unique in her world.

Elsewhere in this book (see pages 218 to 220), we have pointed out that Medical NLP aims for ‘successful’ dissociation as a prerequisite of any substantive change work, rather than as an end in itself. In order for the patient to be able to recode or re-experience her condition, she needs to be guided into an observer-state, effectively removed from her condition, but nonetheless allowing it to be present, temporarily free of the constraints of past or future concerns. This is where, with the guidance of the practitioner, the structure of her problem can be reorganized. After that, she may be re-associated into the more desirable state.

The first Medical NLP algorithm for change, therefore, is:

Dissociate—Restructure—Reassociate

This means simply that the patient ‘steps out’ of her problem, the change is effected ‘over there’, and the changed state, with all its sensory experience, is brought back ‘into her body’. Many ‘bespoke’ techniques can be created using this algorithm.

2. Anchoring revisited

Anchoring, you will recall, involves linking a trigger (visual, auditory, and/or kinesthetic) with a specific response. Thus far, we have used it to stabilize certain resources, largely to help the patient develop a health-and solution-oriented attitude to her situation. We are assuming you have practiced setting and firing anchors with both patients and yourself. Anchors, however, have much wider applications—and, indeed, are central to many, if not all, successful Medical NLP techniques.

Simple anchors

Imagine the possibilities for healing that open up when you simply connect the start (or some aspect) of a problem-state with a more resourceful response. Richard Bandler has described anchoring the sensation of an ambulatory blood-pressure harness monitor against an anxious patient’s chest to feelings of deep calm and relaxation (thus turning a ‘reminder’ of the problem into its ‘cure’), and linking the smell and sight of roses with feelings of massive pleasure to short-circuit an allergic response.208

First create a powerful resource-state by stacking anchors. Then identify the start of the problem-state (or a moment before, if possible) and link this trigger to the resource-state. Repeat until the new sequence replaces the old. If you teach the patient to develop, set, and fire anchors, you will substantially help her deal with her specific problem, as well as providing her with a strategy that will increase her overall sense of self-efficacy.

Case history: A student who reported becoming anxious when giving presentations as part of her college course sought help after being diagnosed with ‘anxiety’ and being offered either cognitive behavioral therapy or medication. From our point of view, this was a classic case of a diagnosis made on the basis of text to the exclusion of context. It emerged that she became anxious at college, and not in front of other groups, suggesting long-term therapy or medication was excessive. Instead, a state of calm confidence was elicited and anchored. She became rapidly adept at firing her anchor and later reported that giving presentations had ceased to be a problem.

(Coincidentally, we have actually seen a training video for new doctors with exactly this scenario. The diagnosis and suggested treatment were the same as for the patient referred to above. At no point did the trainers suggest that doctors should ask whether the problem existed in any context other than college. Therefore, the generic diagnosis of ‘anxiety’ was made. This is an example of the ‘representative heuristic’—and the consequences thereof.)

Collapsing anchors

Similar affective states may be stacked to create complex, intense anchors. Dissimilar anchors will ‘collapse’, resulting in a neutral state, or one that favors the more powerful of the two. This process can be used to ‘extinguish’ unwanted responses caused by a wide range of stimuli.

- Start by creating a strong, ‘positive’, stacked anchor. Do this systematically. Elicit past, strongly positive, experiences, associate the patient into each, and anchor on the same place. Test thoroughly for effectiveness. We highly recommend including ‘the ability to cope’ as a component of the stack. Change state.

- Elicit the unwanted response and anchor it on a different place on the body. Test and change state.

- Fire both anchors simultaneously and observe the patient’s response. Usually, he will display signs of confusion or disorientation. Hold the anchors until these minimal cues subside. Release the negative anchor first, and then the positive anchor.

- Change state and test the patient’s response to the original negative stimulus.

Case history: The patient presented with anxiety and disturbed sleep, complaining that the problem had started when she moved to an apartment near a railway line. Although she said the sound of passing trains was ‘not too bad’, she found herself lying awake, becoming increasingly agitated, expecting one to come past.

A strong, positive anchor of calm and relaxation was set. The negative response was anchored, and then both anchors were collapsed. The patient was given the task of ‘willing’ trains to come along for exactly three days, and was told not to go to sleep on each of those nights until five trains had passed. She reported on her second consultation that she had ‘failed’ to complete the task since she kept falling asleep before the second or third train. (This intervention combined collapsed anchors with ‘prescribing the symptom’, a paradoxical technique developed by Milton Erickson.)

Since almost all Medical NLP techniques involve collapsing anchors (this is explained further in Re-patterning and Future-pacing), either directly or indirectly, the second algorithm for change is:

Establish a Positive Anchor—Identify Negative Anchor(s)—Design a Technique around Collapsing Anchors

3. Chunking

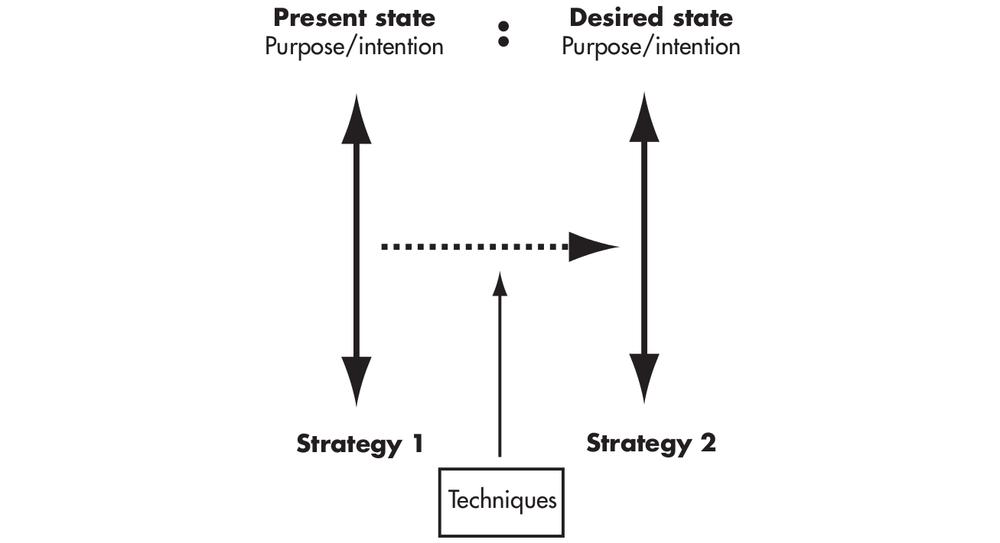

The third core skill involves chunking up for both purpose/intention and down for process or procedure (strategy). Both states, present and desired, need to be chunked in each direction in order to apply this algorithm. By doing so, and, with appropriate framing, the practitioner simultaneously assists the patient to meet the positive intention of her problem and to develop a more appropriate strategy to achieve her desired state (see Structure, Process and Change).

Chunking up for purpose and intention

The example is of a patient who seeks help for ‘drinking too much’. Traditionally, a practitioner might ask when, how much and even why the patient drinks. Two questions we regard as potentially useful are, When did you start? and What caused you to start? Take note of the answers, since these questions place the origins of the problem behavior within the patient’s model of time (see earlier chapter on time and its effects on pathology).

Ensure that the patient understands the concept of positive intention. It is often enough to include this during the normalization stage of the consultation. Most patients respond with relief when we explain that symptoms and behaviors function protectively, and often ‘want something more for you, including getting you to pay attention to some need that may not yet have been met’.

We can add the suggestion that, if the need is ignored, symptoms or behaviors sometimes change or become more intense. This both normalizes changes in the frequency or intensity of symptoms, and presupposes that the patient can take more responsibility for her own wellbeing.

Chunking up for positive intention involves a series of questions, all of which are variations of, ‘What does drinking do for you?’ The answer given (‘It helps me relax’; ‘It gives me confidence’; etc) is acknowledged, and then chunked again. ‘And, when you have [the patient’s reply], what else does that give you that’s even more positive?’

The patient’s response (‘It makes it easier for me to cope’, etc) is acknowledged, and the chunking continues.

‘And, when you have [the patient’s last reply], what else does that give you that’s even more positive?’

When the patient arrives at her core value, she will most likely express it as a nominalization, often with transcendent or spiritual overtones: peace, fulfillment, comfort, etc. Almost inevitably, the core value will represent a protective intention. This must always be respected and the need met by whatever intervention you choose to apply.

The practitioner then asks the patient to recall or create an example of her core value, guiding her into a sensory-rich experience. Anchor the core value.

Chunking down for sequence or strategy

With the core value of the positive intention elicited and anchored, the practitioner begins to chunk in the opposite direction, in order to establish the sequence (strategy) the patient has been using in order to start and maintain her behavior. As explained in Appendix D (see pages 367 to 369), strategies are most easily elicited by first observing the patient’s description of the behavior, noting especially the respective sequences of eye accessing cues and sensory modalities used.

Prompt with variations of these questions: ‘What’s the very last thing that happens before you [the response or behavior]?’ ‘And what happens then?’ ‘And what happens next?’ etc. Continue until the entire strategy has been elicited.

Since a strong neural network already supports the strategy of the problem-state, the new strategy should be adapted to fit the existing sequence as closely as possible. For example, should the patient’s problem strategy involve, say, A > K > V > K, it may be easier to design a new A > K > V > K strategy that results in a positive, rather than a negative, outcome.

For example (using an actual transcript):

Patient: ‘After work, I think: “You deserve to relax; you’ve worked hard.” And then I remember what it feels like to be completely free of all my worries, and I see it like being like a space where no-one else can get at me; the drink is like a barrier all around me. The problem is I know this way is harming me…’

Practitioner: ‘So, when you realize you need to take time out to relax because you’ve worked so hard and can take some time out in another way that’s healthier, which allows you to see yourself in a space where, just for the time being, nobody else can get to you, would you be interested in experimenting with it?’ (This opens the way to exploring and testing alternative strategic routines: yoga, meditation, listening to music, etc.)

However, ensure that any two-point loops (see Appendix D, pages 367 to 369) are taken into consideration, and, if necessary, resolved. Of course, a two-point loop may be a useful inclusion in a positive strategy. Richard Bandler’s ‘the more…the more’ pattern (‘The more you start to worry about [X], the more you remember you have the resources to cope’) is an example of a linguistically installed positive two-point loop reinforcing a patient-centered locus of control.

Mapping across

With both the core value and the strategy of the problem-state identified, the objective now is to map both across to a desired state (Figure 16.1). The intention is to collapse two meta-anchors—the problem-state (PS) and the desired state (DS). For that reason, the desired state must be detailed, desirable and very clearly identifiable to the patient before attempting the transition.

Figure 16.1 Mapping from problem-state (PS) to desired state (DS)

Chunking, especially when identifying strategies, should be meticulous and detailed. It provides large amounts of information that can drive effective change. The third Medical NLP algorithm for change, therefore, is:

Chunk for Purpose/Intention (subjective and experiential), as well as for Strategy/Procedure (objective and sequential).

Chunk across for similar examples of the feeling, response or behavior.

Figure 16.2 Chunking

The patient’s perspective

Not only is the patient the expert on how her condition manifests in her experience, but she also has intuitive resources regarding how well a proposed alternative to her problem-state will fit. This is where you should be particularly alert to her responses to your suggestions. To avoid failure and loss of confidence, it is important not to try to impose overt change without her understanding and complicity, and without fully meeting hitherto unmet needs.

Transition: creating acceptance

Once the purpose or intention of a problem has been established, it is often easiest to invite the patient’s opinion on how to proceed.

Social psychologists (and salespeople) are aware that people’s commitment is often greater to their own opinions and decisions than to those suggested by others. (There are, however, exceptions to this ‘rule’. Older patients and those particularly submissive to the practitioner’s ‘authority’ may readily agree to your suggestions. We strongly recommend that you ensure the patient is fully congruent, whether he is making her own suggestions, or responding to yours.)

Questions that may facilitate patient concordance include:

‘Now we understand your symptom [X] has really been wanting to protect you, how can we find a way that that protectiveness [X] can instead help you achieve your new outcome [Y]?’

‘If you could have [positive intention Y] without having to have [symptom X], how interested would you be in doing that?’

‘We know we need to do something differently if we want a different result. If we can find a different way to do things so that you had more of [negotiated outcome Z], would that be something you would want?’

Once you are confident that you have the patient’s full agreement, test for any suggestions or solutions that might spontaneously emerge:

‘That’s good. Now, just before we begin [allaying performance anxiety], if you could think of a way to do things differently, what would that be?’

Surprisingly, patients often volunteer a new way of doing things.

Recent research reveals that many people have access to more accurate information about their health status than the average doctor—their own insight and intuition.

The answers to the simple questions, ‘How do you rate your own health?’ and ‘Do you have any thoughts or opinions about your situation?’, for example, are more accurate predictors of health and longevity than the most comprehensive tests and medical records.209

If the patient presents an insight or intuition, consider it a gift, and proceed immediately to exploring the suggestion for well-formedness. If it is semantically well formed and is likely to meet the elicited positive intention, proceed immediately to installing it as a strategy.

Installing a strategy

New strategies can be installed in several different ways. These include:

- Anchoring. Elicit the steps in sequence. Anchor each in a different place on the body (the knuckles of one hand may be easiest and least invasive). Fire them repeatedly in sequence until the new strategy runs automatically when the trigger event or feeling is invoked.

- Role playing. This involves practical rehearsal, with the practitioner taking the part of any ‘significant other’ in the patient’s scenario.

- Mental rehearsal. We explore this in greater detail later in the section, Repatterning and Future-pacing.

- Linguistically. The ‘language of influence’—informal hypnosis—is the subject of the following section, Hypnosis in Healing and Health: the language of influence.

All four of these approaches may be employed during the same session. We encourage this approach, known as layering, using several appropriate techniques to ensure strong, new behaviors and responses.

Other approaches to consider

The Swish Pattern in essence collapses one anchor, the problem state (PS), with a stronger, more desirable state (DS), so that the latter extinguishes the former, or creates a ‘neutral’ state. Effective Swish Patterns require:

- a desired state that features at least two, preferably three, sub-modalities (one digital and two analog seem to work best);

- movement from an associated state to a dissociated state (where ongoing behavioral changes, such as healthier eating habits, are intended), or from associated to associated (where a fixed state, such as ‘being a non-smoker’, is the objective); and

- repetition—the Swish should be repeated until the patient cannot easily recover the PS. The patient should open her eyes between repetitions to break state, and always start the next round with the PS, until the PS has been de-activated and the trigger automatically activates the new neuronal pathway to the desired state.

The ‘classic’ Swish Pattern involves setting up the DS as a small, dark square in the bottom right-hand corner of the patient’s visual representation of the PS, and then rapidly expanding the DS while shrinking the PS, accompanied by a ‘sw-i-i-sh’ sound from the practitioner to add an auditory component.

Other variations include:

- putting the DS far out on the patient’s horizon line with the PS in whatever position it naturally occupies, and then rapidly reversing the positions of the two states; and

- concealing the DS behind the PS, and then opening up a window in the center of the PS and rapidly expanding it so the desired state pops through.

Note: Although the Swish Pattern as outlined above relies on strong visual qualities, both auditory and kinesthetic Swishes can be designed, following the same principles. Where a kinesthetic lead is followed, remember the rule that negative feelings are experienced as contracted and localized, whereas positive feelings are expansive.

EXERCISES

Association, dissociation and the Swish

1. Experiment with association and dissociation to become familiar with your own responses. When dissociated from an undesired experience or memory, how would you prefer it to be?

2. Construct the appropriate desired state using all sensory modalities.

3. Chunk both the PS and the DS to establish purpose or intention as well as strategy for each. Explore how you could satisfy the positive intention of the PS with a strategy that is more appropriate than that of the PS.

4. Practice anchoring, role-playing, and mental rehearsal to install the new strategy, and test each one for effectiveness.

5. Practice the Swish Pattern until you have at least three different ways of doing it.

Monitoring levels of wellbeing

1. Make a habit of scanning your body with the following question in mind: ‘How are my patterns of sleep, energy, appetite, general activity now, compared with last week (or month ago)?’ If any of these are markedly worse, take whatever steps are necessary to explore further. (This exercise is not intended to foster hypochondria, but, rather, to help you attune to fluctuations in your health and wellbeing that only you can detect, and which may prove significant.)

2. Ask similar questions of your patients in order to measure their levels of health, wellbeing and ikigai.

Notes

204. Frankl V (2004) Man’s Search for Meaning. London: Rider & Co.

205. For an extensive review of research into our human tendency to act out of the rules of group thinking, we know of no better book than David Berreby’s Us and Them—Understanding Your Tribal Mind (2005) London: Hutchinson.

206. Langer E (1989) Mindfulness. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

207. Furedi F (2004) Therapy Culture: Cultivating Vulnerability in an Uncertain Age. London: Routledge.

208. Conversation with the author (GT).

209. Gilbert K (2006) The Doctor is Within, Psychology Today, September/October.