CHAPTER 6

Design Thinking

Chapter 5 conveyed tips for cultivating systems thinking. In this chapter, I introduce design thinking so you can add it to your repertoire of school transformation tools. First, let’s examine the different levels of complexity in systems and a rule of thumb rubric for applying appropriate approaches.

Addressing Complexity

Without first understanding the context of any given situation, it’s difficult to apply design thinking.

The Cynefin framework is used to support decision-making (Snowden & Boone, 2007). The Cynefin framework, named after the Welsh word for habitat, was created by Dave Snowden when he worked at IBM Global Services (Snowden, 1999). It has been updated and revised several times in collaboration with his colleagues at Cognitive Edge (https://cognitive-edge.com/blog/cynefin-st-davids-day-2020-1-of-n/). The framework identifies four domains, or levels, of complexity and provides guidance for addressing problems or making decisions within each of these levels. The dark center represents the domain of confusion, when we don’t know which domain we are in.

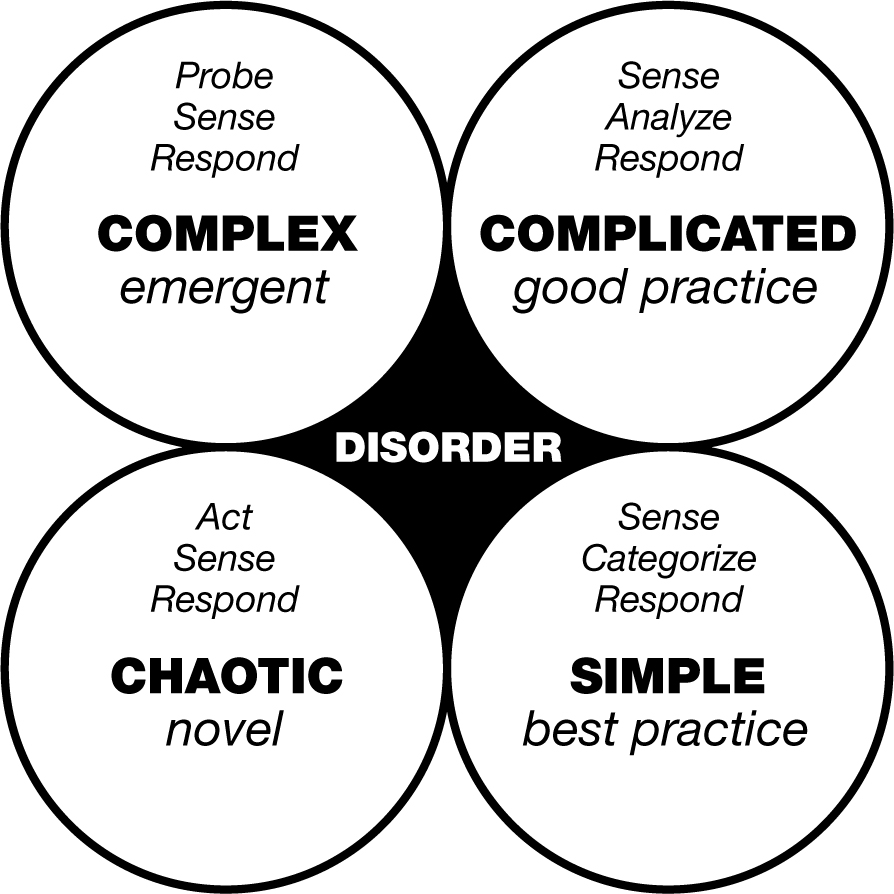

FIGURE 6.1 Simplified Cynefin Framework created by author with permission from Dave Snowden

As you can see in Figure 6.1, the four domains can be mapped out in a rubric where each of the quadrants represents one domain. The clear domain represents the “known knowns.” There is clearly an existing best practice for the situation, and the situation is stable. The cause–effect relationship is obvious and the constraints are fixed. The best way to respond in this domain is to “sense-categorize-respond.” This means we can clarify or sense the facts of the situation, categorize it, and then respond by applying best practice.

The complicated domain holds the “known unknowns.” The cause–effect relationships are not obvious, and expertise is required to discover them. In this domain, there are a range of right answers, and the framework suggests “sense-analyze-respond” under these conditions. Again, we begin by sensing the facts, but then we analyze the situation, and finally we apply an appropriate practice to the situation. In this domain, a decision requires refined judgment and expertise.

The “unknown unknowns” are prominent in the complex domain. There are no right answers, and various cause and effect relationships can only be recognized retrospectively. This requires a lot of brainstorming, experimentation, and trial and error so that the best response can emerge. This process calls for “probe-sense-respond.” We probe to gather information, we sense what will work and then we respond by testing various hypotheses.

When the cause and effect relationships are completely unclear, we are in the chaotic domain. Events can be extremely confusing, and taking action is the only way to respond. In this domain we can “act-sense-respond.” As mentioned in the Chapter 5, we can turn a vicious cycle into a virtuous cycle by creating a gap in the cycle. Therefore, in the chaotic domain we act to establish order and then sense how best to create stability. In this way, we can transform a chaotic event into a less complex event that is more manageable. From this point, we can identify some emerging patterns to prevent the chaos from reemerging and recognize new opportunities for responding.

The black area at the center of the framework represents confusion when it’s unclear which domain applies. It is difficult to recognize this domain because of the nature of the confusion. It’s a point of cognitive dissonance where one needs to pause and deeply reflect to find one’s way out of confusion to see the nature of the problem.

Healthcare professionals responding to the COVID-19 epidemic is a great example of working in the chaotic domain. Since the virus is novel, doctors had no tested protocols to draw upon. They had to quickly assess what each patient needed and attend to the most severe cases immediately. As patients were stabilized, doctors began trying different approaches to support patient recovery. Over time, they learned what worked and what didn’t work.

According to the Cynefin framework, as knowledge and expertise are acquired, events can shift from chaotic to simple. However, this shift can result in the development of biases; complacency grows from relying on simple solutions when the event is not as simple as we think. Mind traps can play a role in this process. I might fall back on a simple story to explain something that I think is familiar but that is actually novel, but I don’t recognize it. I may then think I’m right and get stuck using the approach for a simple system on a system that is actually much more complex. This can result in a rapid failure in which the situation quickly slips into chaos. Again, the COVID-19 pandemic provides an example. At first many believed that the virus was like a typical flu, and that it would likely resolve quickly. This led to a serious underestimation of the threat and a series of missteps in the response.

Now let’s apply the Cynefin framework to classroom management. In my book The Trauma-Sensitive Classroom (Jennings, 2019b), I present action steps for problem-solving behavior issues (pp. 102–103). These align well with each of the domains. During each of these stages, teachers are encouraged to engage in self-reflection: recognizing what emotions are involved, considering whether they are taking the behavior personally, considering biases and scripts that might play a role in the situation, and taking a few breaths to calm down before proceeding with any actions.

Stage 1 is routine maintenance, which aligns with the clear domain in which there are “known knowns” and best practices to guide our actions. In the clear domain we “sense-categorize-respond.” I recall one year when a teacher I was supervising told me she was having behavioral challenges with a young child named Aisha. Ms. Andreyev complained, “She is just not listening! She’s always bothering the other children and doesn’t respond to my instructions.”

Sensing the situation, we tried the Stage 1 routines based on our categorization of her behavior. These included reminding, reinforcing, redirecting, and logical consequences, which together are a positive behavioral response that is respectful (versus punitive), reasonable (proportionate to the misbehavior), and helpful, in that it promotes learning. Logical consequences can be simplified by these three possibilities: you break it, you fix it; loss of privileges; or a positive time out (Jennings, 2019b, p. 94). These approaches work in a simple context. Most children respond to them quickly. However, Ms. Andreyev and I tried them all to no avail; it was clear that we had a more complicated situation on our hands, so we considered Stage 2.

Stage 2 aligns with the complicated domain and involves engaging in “sense-analyze-respond” problem solving. We took some time to speak to Aisha’s mother and learned that Aisha was having similar problems at home. I also spent a few hours observing Aisha and interacting with her in class. As I applied my expertise to my observation, I began to sense that she wasn’t hearing me. It was difficult to detect because she was actually managing fairly well with body language, but her verbal language was delayed, and that was a red flag. Analyzing the situation, I concluded that she had a hearing problem that was interfering with her responsiveness to adult direction and interactions with her peers. As soon as I had this insight, I called the mother and asked what she thought about my assessment. “Wow, I think you are right. I’m so sorry I missed this,” she said. All of a sudden, a complex situation became quite simple and she took Aisha to the pediatrician for a hearing test right away. I was correct, her ears were completely blocked and she needed tubes. Once the tubes were implanted, Aisha could hear fine and her behavior improved dramatically.

If the problem had not been resolved at this point, we would have moved to Stage 3, which aligns with the complex domain. This stage is designed to address chronically inappropriate behavior and requires the “probe-sense-respond” approach. We would have engaged other school personnel in probing the issues, such as inviting the parents to meet with us and asking the school psychologist to conduct an evaluation. This may have led to a referral for special education services to meet the complex needs of the student. The special education teacher and the school psychologist would then work with the teacher and the parents to understand the student’s behavior and create plans to address it.

While there is no Stage 4 in the action steps model, we’ve all been in a situation when our classroom has turned into bedlam. This aligns with the chaotic domain. Under these conditions, we have to do something immediately to stop the chaos before someone gets hurt. Often the go-to response is to yell at the students, but often yelling just adds to the chaos. I find that it works better to do something unexpected to draw their attention and then engage in some simple calming and focusing practices afterwards.

For example, years ago I was teaching anatomy to a group of fifth graders. We were studying bones and muscles, and I always like to come up with hands-on learning activities, so I had the bright idea of asking them to bring in a specimen to examine, a bone or a piece of meat. I had not planned ahead very well and when the class began, they all took out the bones and meat they had brought and started teasing each other with them, holding them and shaking them in each other’s faces—there’s nothing like total chaos with raw meat. You can imagine my mortification. I immediately recognized that this was a really bad idea. It wasn’t sanitary, and the kids were not being respectful to their specimens or their peers.

I had to think quickly to come up with a way to halt this failed experiment, so I grabbed a plastic bag out of the classroom garbage can and began singing the “Dem Bones” song very loudly, “Toe bone connected to the foot bone. Foot bone connected to the heel bone.” Once I had their attention, I told them that I had made a big mistake and that what they were doing could be dangerous. I held out the bag, and they put the meat in the bag and I threw it away. What a mess. After the meat and bones were discarded and everyone had carefully washed their hands with soap and water, we spent some time taking deep breaths to calm down.

In retrospect, I see so many more problems with this assignment. It was a real waste to throw away the meat. Some students likely did not have the resources to bring in what I had asked. Some might have come from vegetarian families. So, I certainly discourage you from trying this in your classroom. But it was a great example of a classroom in chaos and of a quick and easy way to establish order.

What Is Design Thinking?

Now that we can analyze the type of system we are dealing with, we can see how to cultivate design thinking so we can apply it to studying the needs of our students, classrooms, and school. Design thinking is a mindset based in the belief that we can make a difference by applying an intentional process to generate novel solutions that result in positive outcomes. It can give you the confidence you need to address challenges in complex systems.

The design thinking movement emerged from engineering science to spark innovation in private industry to solve “wicked problems” (Rittel & Webber, 1973). Wicked problems are difficult to solve because they do not have one obvious solution. They arise from the interaction of multiple perspectives, values, and possibilities. They require that a variety of tools from different disciplines be applied simultaneously. In other words, these are problems that arise in complex systems. Applied to human systems, design thinking democratizes the design process because it allows every person to think and act like a designer, a person who uses the design process to improve a situation or solve a problem.

Design thinking has made its way into education as a complement to project-based, collaborative learning and the maker movement. While it’s critical to support our students’ design thinking, we can also apply it to designing the classroom and school to address our current and future needs. Designers manifest their intention in the form of a specific outcome based in a thinking process. As educators, we are constantly designing our schools, curriculum, classrooms, schedules, lesson plans, and classroom activities. However, we are often functioning as designers unconsciously. By understanding and applying design principles, we can bring more intentionality to our work, thereby achieving greater impact.

In Chapter 5, we learned about how our mindsets can trap us in unproductive ways of being and how to recognize and overcome such traps to be able to see situations from a wider perspective, one that recognizes the complex interacting systems involved in any process. To add design thinking to our repertoire, we extend this flexible and growth mindset to designing solutions to challenges in our system, whether it be the classroom or the whole school.

Design thinking is focused on human needs and requires collaboration to bring multiple perspectives to the table. Design thinking is experimental, and failing is highly valued because that’s how you test new ideas quickly. Design thinking does not have a clean and simple goal. It’s an ongoing creative process that opens up vast possibilities through learning by doing. Finally, it’s an optimistic approach because it assumes that there is no challenge too difficult to address.

Design thinking can be used to address any challenge, from how we arrange our classroom to designing learning experiences so the content is more closely aligned to our students’ interests and needs. You can use it to rethink some of the processes occurring in your school such as scheduling, school discipline policies, and age-grouping.

Begin by being “user” centered. In this case, the “user” is the student. Recognize the talent, skill, and intelligence in the organization, regardless of status. This means recognizing that each and every student has something important to offer the design process. You will need to step out of your comfort zone to experiment and to test novel solutions. Thus, we need to create safety for ourselves and our students, so we value questions of all kinds and failures—the quicker we fail, the better because learning what doesn’t work is important.

A critical part of the design process is brainstorming possibilities and becoming comfortable with the chaos and confusion that can arise during deep learning. In this chapter we will explore the functions of the designer that you can apply to your classroom and your school teams can apply to the whole school. With these functions in mind, you will have the tools to intentionally design the change you wish to see in your school.

There are various models of the design thinking process, but they all share the same fundamental elements: empathizing with and understanding the needs of the user(s), engaging in divergent thinking cycles to draw upon diverse sources of inspiration, learning through rapid prototyping and testing, and then scaling and monitoring to ensure needs are being met at scale. This process is nonlinear, messy, and can be time consuming. It may feel uncomfortable at first, because we’re so used to rigid, top-down processes. However, you will find design thinking incredibly empowering, and with the increasing complexity of our systems, the only effective way is to consider as many possibilities as we can and to allow novel solutions to emerge from the input of the community.

Design thinking involves a series of recursive processes, comprising an oscillation between divergent and convergent thinking modes, that are all supported by deep reflection. In education, we often consider reflection as critiquing something that we have done. In this context, it’s deeper, in that we do more; we also consider how we feel, notice what we are thinking, and allow our wonderings and intuitions to arise in the process. The first step is to examine our identities by questioning ourselves: our values, emotions, biases, and assumptions. Make a list of everything you know about the situation you are addressing in the designing process. This includes the people and the environment and how these interact with the larger system (e.g., classroom, school, district). Then, begin to examine whether there are biased assumptions in this list. Ask yourself, “How do I know this?” Identify areas where you need more information, be it about the people, the environment, or the process. This leads us to wondering about the situation, and we begin to formulate questions. Throughout the process, remember that you are a designer making intentional decisions for a positive outcome. Embrace your beginner’s mind by being open to experimentation and possibilities rather than quickly assuming you have the right answer. To learn, we need to get out of our comfort zone to take risks and make mistakes. Try new things, break the routine, collaborate with others within and outside of the school, and have fun! Remember that challenges are design opportunities. You can be the system change you wish to see in the world.

Empathize

When folks in private industry apply design thinking in their work, the focus is squarely centered on the user. Understanding and empathizing with the user is where the design process begins (Kelley & Kelley, 2015). Who are they? What’s important to them? What do they need? What’s their perspective?

As I described in Chapter 5, one great way to develop empathy for your students is the Student Interview (Jennings, 2015, p. 135). This is simply spending a few private minutes with each student, getting to know them better as well-rounded whole people, not just as students. I have introduced this exercise to many teachers as part of the Cultivating Awareness and Resilience in Education (CARE) program, a mindfulness- and compassion-based professional development program for teachers that helps them manage the stress of the classroom and build emotionally supportive learning environments (Jennings, 2016; Jennings et al., 2017). To introduce this exercise to you, I would invite you to interview one student you wonder about or find particularly troublesome in some way. Tell this student that you’d like to spend a few minutes getting to know them better and schedule a time during a break to speak with them. Ask the student a variety of ordinary questions that may be relevant to students of their age. For example, you might ask, “Do you have any pets?” “How many people are in your family? Will you tell me about them?” “What’s your favorite food?” As the student is speaking, listen mindfully with your full attention while tuning into them, building a connection. Don’t worry about what you’re going to say next. How is the student feeling right now? How are you feeling right now? Allow the feelings to guide your questions. If you find something that really excites the student, probe further to learn why and how they might be encouraged to bring this aspect of their life into the classroom. You’ll be surprised what insights can arise and how this simple interaction can transform your relationship with the student.

One example of a dramatic transformation was a story Ms. Rogers told us at a follow-up workshop when participants were asked to share their experiences. Ms. Rogers told us about Missy, a kindergartener who had not yet said one word in school. It was November, so she was beginning to have some serious concerns about the girl. Missy had attended pre-K at the same school and the pre-K teachers had told Ms. Rogers that Missy hadn’t said one word the entire year. Applying what she learned in the CARE program, Ms. Rogers realized that the school was starting to create a script about Missy, that something was wrong with her. She could feel the stereotype forming and wanted to nip it in the bud. But to do so, she needed to understand Missy better so she could empathize with her. She told Missy that she was taking a class and that one of her assignments was to interview one of her students, and she asked Missy if she could interview her. Missy nodded her head, beaming, and they made a plan to meet during recess that day. During recess, Ms. Rogers invited Missy to come sit with her, away from the other students on a bench under a shady tree. Ms. Rogers had a note pad on her lap and was holding a pen.

“Thank you for letting me interview you, Missy. My first question is: Do you have any pets at home?”

Missy smiled and began telling her about their dog, Peanut. “He has brown hair, and he’s about this big,” she said, holding her hand up to her knee, which was at the level of the bench.

Ms. Rogers was astounded and relieved to learn that Missy could talk and was actually quite articulate. She asked her more questions about Peanut and learned that he knew how to fetch a ball. As Missy answered each question, Ms. Rogers wrote down every answer on the notepad. We encourage teachers to do this because it lets the student see that we are taking what they are saying very seriously and that we really care about what they have to say. Ms. Rogers shifted to questions about Missy’s favorite toys, movies, books, colors, food, and ice cream. She learned that Missy had one older brother and three cousins, who live nearby.

At the workshop, Ms. Rogers ended the story by telling us that since that day, Missy has spoken during class just like the rest of her students.

“It makes me realize how much our students really need to be seen and heard and how sad it is that she didn’t feel ready to speak at all during her pre-K year.”

One teacher participant conducted the student interview with one of her students, and the other students expressed their desire to have a chat with her too, so she spoke with each of them individually over the course of several weeks. She later reported that she observed a transformation in her classroom culture, the interactions between her and the students, and among the students. The students were much more positive and engaged.

Recently several blog posts written by teachers who shadowed students in the schools where they worked, to understand what being a student there is like, have gone viral. For instance, Ms. Redd and Ms. Wiggins spent a whole day doing the same thing the students they followed did. Both teachers found sitting passively all day exhausting. They both complained that by the end of the day, they felt lethargic and mentally drained. Ashley Redd (2020) shadowed a fourth grader for a day at her school. She “went home with a migraine, a backache, and a hangover of fear and humiliation.” The experience was so alarming that she is considering leaving the profession. The teachers she witnessed were so stressed that they had little patience with normal student behaviors, such as socializing in the cafeteria. Ms. Redd left feeling that the primary aim of the students was to avoid getting into trouble. Alexis Wiggins (Strauss, 2014) shadowed two students at the high school where she worked as a learning coach. The first day, she shadowed a 10th grader, and the next day she followed a 12th grader. She noticed how often teachers’ impatience made her feel afraid of asking a question.

There are many other ways to learn about and empathize with your students. You can simply observe them in action with “beginner’s mind,” a mind that is open to new possibilities. You can do informal focus groups with your students to learn about their perspectives and interests. You can encourage them to dream big and imagine what they might do and learn in school.

As you’re getting to know your students, avoid pigeonholing. As we learned in Chapter 5, it’s easy to create simple stories about others that are simply wrong. There are numerous stereotypes that we hold about students: the teacher’s pet, the troublemaker, the class clown, the smart kid, etc. Avoid falling into this mind trap by intentionally looking for the wide diversity of all kinds within and among your students, with an eye for gems of difference that can make a valuable contribution to your classroom, such as the student who loves to draw and is really talented; the student who is an avid sports fan and can name all the players in every team along with their stats; the student who thinks differently, for whatever reason. They are all part of this rich tapestry of human gifts we can engage, nurture, and draw upon.

Understanding the Challenge

After building empathy with the user, the next step in the design thinking process is to identify the design challenge and consider how best to approach it. This is a good time to use the Cynefin framework to determine the challenge’s level of complexity. As you begin to learn this process, you might want to start with challenges that are complicated, but not too complex. As you learn and develop design thinking skills, you’ll be able to tackle more complex challenges.

Once you have identified a challenge, remind yourself to frame it as an opportunity by stating it as a series of “how might we” questions. Write down the challenge in simple language. Next decide on goals for the design challenge. You might want to create a timeline of action steps. What are the deliverables and when should they be delivered? Next define the measures of success. How will we know when we have met the challenge? These should be concrete, measurable outcomes. You may come up with additional outcomes as you move through the process, but it’s good to have a basic idea up front. Be sure to define constraints to keep you on track. I’ve found that, during the design process, it’s easy to get lured into going down a rabbit hole, following some interesting idea that is completely irrelevant.

Breckenridge Elementary school faced a challenge with scheduling. Several of the teachers wanted to experiment with longer work periods because they felt the schedule was forcing them to stop in the middle of deep learning for transitions, and the shrill bell was annoying. They were experimenting with collaborative, project-based learning and found their students had to quit right as they were figuring out how to solve a problem. The principal encouraged teacher experimentation and leadership, and she invited these teachers to come up with a new schedule design.

A team of six teachers gathered to apply design thinking to the challenge. First, the team spent time talking to each teacher to learn about what they needed from the schedule. They observed some of the classes in which teachers felt they didn’t have enough uninterrupted time. This helped the team empathize with the teachers so that they could tailor the design to meet the teachers’ needs. In this case the question was “How might we arrange the school schedule so there are longer periods of sustained engagement in learning?” They hoped to design a schedule that accommodated these longer work periods without disrupting the schedule of special periods (e.g., art, library, and PE), lunch, and recess. Since school was already in session for the year, they realized that this change would need to wait until the following school year, which gave them plenty of time to work on the design challenge. They defined success as “Every student has at least one 90-minute time period for sustained learning engagement per day, and every student has two special classes per week.” The team wrote a brief that outlined the problem and proposed goals, a timeline, and desired outcomes. They presented the brief in a slide show at the next faculty meeting, where they received considerable feedback from the other teachers. Most thought it was a good idea, but many were skeptical that it would be possible to make such a change.

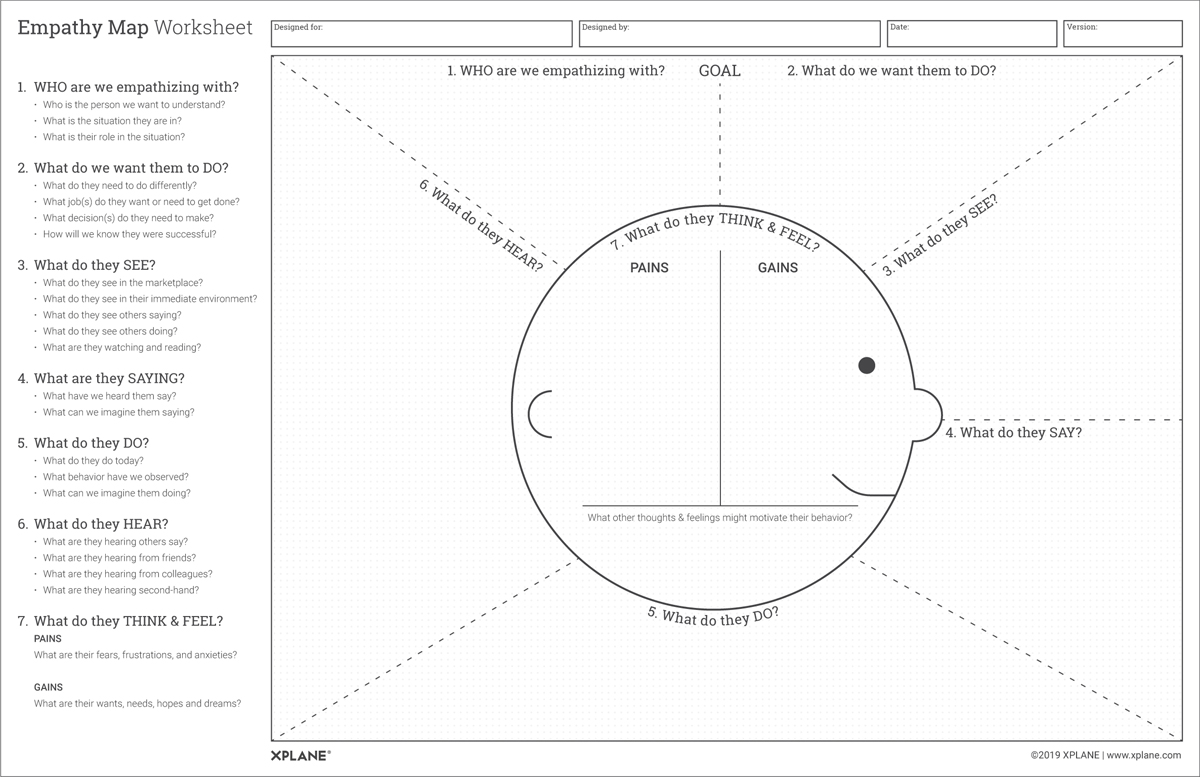

Needs and Insights

To apply the empathy process to recognizing the needs of and gleaning insights from your user, you can create an Empathy Map (Gray, 2017). This tool can be applied to understanding the needs of an individual, a group, or your entire class or school staff. In Figure 6.2 you will see a diagram of the Empathy Map Canvas from Dave Gray’s blog “XPlane.” Starting at the top, the first two questions center on the goal of the process: Who are we empathizing with and what do they need to do? The answers to these questions should be framed in terms of observable behaviors. Next, work clockwise around the map completing the Seeing, Saying, Doing, and Hearing sections. These sections are opportunities to reflect on observable phenomena that can provide insight into what it feels like to be the user. Next you focus on what is going on inside their heads with the question: What do they think and feel? Examine their pains and gains, what they fear or are frustrated about, and what they want, hope, and need.

FIGURE 6.2 Empathy Map Canvas Worksheet

Source: Created by XPLANE

As you observe the user engaged in their own problem-solving, you can begin to recognize places where their learning can use a nudge. If you discover a “wicked problem,” you can brainstorm to find as many creative solutions as possible. All solutions are considered. Nothing is too crazy to mention. It helps to limit comments such as “Yes, but” and replace them with “Yes, and…”

Often, we can manage this process on our own, but it helps to engage with a team. This can occur in IEP/504 meetings that include several members of the school staff, the parents, and sometimes the student. School leaders can apply design thinking to these meetings to find novel solutions to sometimes intractable problems with student learning and behavior. For example, Larry Dailey (2016) reported on an IEP meeting that was transformed by applying systems thinking to the student’s needs. The meeting began with a state-appointed facilitator trying to run the meeting and control the agenda. As tensions arose, the parents became so upset that they withdrew their consent, and the facilitator left the meeting before it was finished. Since everyone else remaining in the room wanted to complete the meeting and the IEP process, they decided to reset and apply design thinking to the meeting format. He noted:

So, instead of listening to lengthy, preformatted presentations from only a few of the meeting’s participants, we agreed that everybody in the room would take turns presenting one thought at a time. Each idea would be posted on a sticky note and placed on a table. Posted ideas would be brief, so that we could build on them later. The parents’, teachers’, child’s, and administrators’ contributions would all be treated equally. And we agreed that everybody would present at least three ideas (Dailey, 2016).

After all the ideas were out on the table, the group began considering and prioritizing them and came up with novel solutions that they all felt good about. Even the student left saying that the meeting was fun!

The next step in the design process is to build a prototype. You can do this as a drawing or a model, whichever will get your ideas across. This should be like a rough draft. Remember to maintain flexibility at this stage. It’s easy to get attached to our ideas (thinking we’re right or that there’s a simple story), so be careful not to fall in love with your ideas. Once you have a prototype, test it by experimenting. This can be a real test run, a process, or a thought experiment trial. During this process, be sure to encourage honest feedback and allow for repetition of the prototype testing process. It usually takes several iterations to come up with a great solution.

Throughout this stage, everyone engages in deep reflection so be sure to make time for the reflection process. Sometimes it takes time for insight to arise, so create the space and time for this to occur. Remember to check in with how everyone is feeling. Make sure there’s time and safety to work out any uncomfortable feelings.

Brainstorming

Once you have empathized with the user and acquired insight regarding their needs, it’s time to brainstorm ideas. This is where the divergent thinking happens, so it’s good to set some ground rules to promote exploration. It also helps to have someone act as a facilitator to lead the team through the process and to start with a warm-up activity to get your team in the mood to brainstorm. At this stage, there are no bad ideas, so put on the table any ideas that emerge. Welcome wild and seemingly crazy ideas. Even if an idea is totally unrealistic, it might spark another way of thinking about the challenge that will result in a novel solution. The process involves scaffolding ideas on one another by thinking “and” rather than “but.”

Remember to keep your brainstorming session focused on the specific challenge by writing it on a board or chart, because it’s easy to get side-tracked during this stage of the design process. Be sure everyone in the team has the tools they need to share ideas, such as pens and Post-it pads. Then ask each person to write the first idea that comes to mind. This gives each team member an opportunity to consider an idea without input from teammates. Facilitate the brainstorming by inviting team members to share their ideas. Ensure that everyone involved has an opportunity to voice an idea. Monitor the time each person takes, and make sure no one is dominating the stage. Use chart paper to illustrate ideas. Sometimes a simple diagram is easier to grasp than a complex explanation of an idea. Aim for lots of ideas; the more, the better.

Going back to the story about our school schedule challenge, the team gathered, and one teacher, Mark, facilitated. Once the team had completed the warm-up steps and gone over the ground rules, they all wrote their first ideas on Post-its. Nadine wrote “eliminate the schedule,” which she knew was a totally crazy idea. When they began sharing ideas, everyone chuckled when Nadine shared, but her idea did get them thinking about what the schedule in the school is actually for. As they brainstormed, they began to realize that they had to stretch their thinking to get out of the old factory model framework of regimented time schedules. This freed them to explore many more “crazy” ideas, and they challenged each other to see who could come up with the craziest idea. By this time, they were all laughing and joking about the challenge and the crazy solutions, but soon they had a large batch of sticky notes on the wall.

The next step in the process is to spend a few minutes grouping together similar ideas. Mark began to put all the “crazy” ideas over to the side when Marsha had an insight, “Wait, don’t put that one in the crazy pile. I think it should stay with the rest.” This idea was to let students create their own schedules. While it was hard to imagine how this idea was feasible, Mark put it back in the group of ideas they were considering. Next Mark invited the team to choose their favorite idea by marking it with a bright pink dot. Then they discussed the favorite ideas, and afterward, Mark asked them to pick three from the six.

Converging and Emerging

The teachers had employed an emergent thinking process to come up with several solutions. Based on the ideas and who originated them, they broke into three pairs to illustrate each of the ideas. As Nadine and her partner began to diagram their idea on a piece of chart paper, they continued to brainstorm how they might bring the concept to life so others would understand it. They had decided to focus on the simplest solution possible, which involved beginning each day with an approximately 20-minute morning meeting followed by a 90-minute work period. Each teacher could decide which content area, or areas, they would use this for. The use of this longer work period could be consistent or vary from day to day, depending on the situation. Special teachers could use the time for planning and for assisting other teachers with learning activities. Special classes would begin right after the 90-minute work period, and each class would have their special periods scheduled at the same time of the day. This gave each teacher a planning period at some point during each day and created a consistent routine for the students. As they thought this through and created the diagram, they questioned assumptions and thought through possible unforeseen consequences. Then they were ready to share their ideas with the team.

Overall, the team found their proposal intriguing. The team gave them constructive feedback and came up with a few possible issues that Nadine and her partner hadn’t considered. After each group presented their ideas, the team settled on refining Nadine’s idea. They examined the solution in greater depth and mapped out a hypothetical day that included every grade and class. They made a list of possible barriers. For example, they knew that the special teachers might not want all their free time at the beginning of the day. Through the process, they refined the idea to the point where they felt ready to share it with the school community. They even came up with a name for the idea, “Flex Time.” Nadine used her smartphone to take photographs of the charts and sticky notes to document the entire process so what they had learned would not be lost.

The team presented their idea at the next faculty meeting. One colleague highlighted a few issues they had completely forgotten about. For instance, due to limited space, the school had to use the gymnasium for recess on rainy days, which would interfere with one of the daily PE special sections. The team realized that they would have to go back to the drawing board, revisit the other ideas, and brainstorm some new ideas. While this was disappointing, it gave them an idea for creating a better visual of the school schedule so they could juggle all these variables. At their next team meeting, they created a diagram of the entire week and the elements of the schedule, and they used different colors of paper for each class. As they played around with the model, new ideas began to emerge.

As you can see, the design thinking process involves a series of repetitions of divergent thinking and converging on possible solutions. It involves finding ways to map out or illustrate an idea to share it with stakeholders. Feedback from numerous stakeholders can help identify problems with the idea so that it can be further refined. In some cases, you might want to pilot test the idea or create a prototype. In this case they couldn’t pilot test the idea, but they were able to create a realistic model of all the possible ways to rearrange the schedule. Because they had the whole school year to work on this, they had plenty of time. As the end of the school year approached, they began to settle on a novel idea. They designed a schedule that began with a 30-minute morning meeting followed by four 90-minute blocks. One of the blocks was split in half for lunch and recess. This resulted in longer special classes, but there were fewer each week. It also gave teachers much more flexibility to create their own schedules with long blocks of uninterrupted time. When they presented this idea to the faculty, they found that the special teachers really liked the idea. “We always lose so much time during the transition to and from the gym that we don’t have a full period to complete activities as it is,” said the PE teacher. The art teacher was also happy to have longer class periods. Except for lunch, recess, and specials, the plan otherwise left scheduling up to individual teachers. If teachers wanted to schedule longer blocks of learning time, that was up to them. They could also vary the amount of time they spent on each subject from day to day. Overall, the teachers appreciated the prospect of having autonomy over their schedules and the principal was happy to eliminate the need for the bell.

This concludes Part II of this book. In the next section, you’ll see how we, the teaching workforce, can elevate our profession, transform our teaching and learning environments, and cocreate a new story about the important work we do and how it can contribute to society’s progress over this century.