lupines on Schoodic Peninsula

MOUNT DESERT ISLAND “DISCOVERED”

Corea’s harbor.

Maine is an outdoor classroom for Geology 101, a living lesson in what the glaciers did and how they did it. I tell anyone who will listen that I plan to be a geologist in my next life—and the best place for the first course is Acadia National Park.

Geologically, Maine is something of a youngster; the oldest rocks, found in the Chain of Ponds area in the western part of the state, are only 1.6 billion years old—more than two billion years younger than the world’s oldest rocks.

But most significant is the great ice sheet that began to spread over Maine about 25,000 years ago, during the late Wisconsin Ice Age. As it moved south from Canada, this continental glacier scraped, gouged, pulverized, and depressed the bedrock in its path. On it continued, charging up the north faces of mountains, clipping off their tops, and moving south, leaving behind jagged cliffs on the mountains’ southern faces and odd deposits of stone and clay. By about 21,000 years ago, glacial ice extended well over the Gulf of Maine, perhaps as far as the Georges Bank fishing grounds.

But all that began to change with melting, beginning about 18,000 years ago. As the glacier melted and receded, ocean water moved in, covering much of the coastal plain and working its way inland up the rivers. By 11,000 years ago, glaciers had pulled back from all but a few minor corners at the top of Maine, revealing the south coast’s beaches and the intriguing geologic traits—eskers and erratics, kettle holes and moraines, even a fjard—that make Mount Desert Island and the rest of the state such a fascinating natural laboratory.

Mount Desert’s Somes Sound (named after pioneer settler Abraham Somes)—a rare fjard—is just one distinctive feature on an island loaded with geologic wonders. There are pocket beaches, pink granite ledges, sea caves, pancake rocks, wild headlands, volcanic dikes, and a handful of pristine ponds and lakes. And once you’ve glimpsed the Bubbles—two curvaceous, oversize mounds on the edge of Jordan Pond—you’ll know exactly how they earned their name.

Acadia National Park fits into the National Weather Service’s coastal category, a 20-mile-wide swath that stretches from Kittery on the New Hampshire border to Eastport on the Canadian border. In the park and its surrounding communities, the proximity of the Gulf of Maine moderates the climate, making coastal winters generally warmer and summers usually cooler than elsewhere in the state.

Average June temperatures in Bar Harbor, adjoining the park, range 53-76°F; July-August temperatures range 60-82°F. By December, the average range is 20-32°F.

Maine has four distinct seasons: summer, fall, winter, and mud. Lovers of spring weather need to look elsewhere in March, the lowest month on the popularity scale, with its mud-caked vehicles, soggy everything, irritable temperaments, tank-trap roads, and occasionally the worst snowstorm of the year.

Summer can be idyllic—with moderate temperatures, clear air, and wispy breezes—but it can also close in with fog, rain, and chills. Prevailing winds are from the southwest. Officially, summer runs June 21-September 23, but consider summer to be June, July, and August. The typical growing season is 148 days long.

A poll of Mainers might well show autumn as the favorite season—days are still warmish, nights are cool, winds are optimal for sailors, and the foliage is brilliant—particularly throughout Acadia. Fall colors usually reach their peak in the park in early-to-mid-October. Early autumn, however, is also the height of hurricane season, the only potential flaw with this time of year, although direct hits are rare.

Winter, officially December 21-March 20, means an unpredictable potpourri of weather along the park’s coastline. But when the cold and snow hit this region, it’s time for cross-country skiing, snowshoeing, and ice-skating. The park receives an average of 61 inches of snow over the season.

Spring, officially March 20-June 21, is the frequent butt of jokes. It’s an ill-defined season that arrives much too late and departs all too quickly. Spring planting can’t occur until well into May; lilacs explode in late May and disappear by mid-June. And just when you finally can enjoy being outside, blackflies stretch their wings and satisfy their hunger pangs. Along the shore, fortunately, steady breezes often keep the pesky creatures to a minimum.

A northeaster is a counterclockwise-swirling storm that brings wild winds out of—you guessed it—the northeast. These storms can occur at any time of year, whenever the conditions brew them up. Depending on the season, the winds are accompanied by rain, sleet, snow, or all of them together.

Hurricane season officially runs June-November, but hurricanes are most active in late August-September. Some years, Maine remains out of harm’s way; other years, head-on hurricanes and even glancing blows have eroded beaches, flooded roads, splintered boats, downed trees, knocked out power, and inflicted major residential and commercial damage. Winds—the greatest culprit—average 74-90 mph. A hurricane watch is announced on radio and TV about 36 hours before the hurricane hits, followed by a hurricane warning indicating that the storm is imminent. Find shelter away from plate-glass windows, and wait it out. If especially high winds are predicted, make every effort to secure yourself, your vehicle, and your possessions. Resist the urge to head for the shore to watch the show; rogue waves combined with ultrahigh tides have been known to sweep away unwary onlookers. Schoodic Point, the mainland section of Acadia, is a particularly perilous location in such conditions.

Sea smoke and fog, two atmospheric phenomena resulting from opposing conditions, are only distantly related. But both can radically affect visibility and therefore be hazardous. In winter, when the ocean is at least 40°F warmer than the air, billowy sea smoke rises from the water, creating great photo ops for camera buffs but seriously dangerous conditions for mariners.

Fog adds an element of mystery to the Acadia landscape.

In any season, when the ocean (or lake or land) is colder than the air, fog sets in, creating nasty conditions for drivers, mariners, and pilots. Romantics, however, see it otherwise, reveling in the womb-like ambience and the muffled moans of foghorns.

The National Weather Service’s official daytime signal system for wind velocity consists of a series of flags representing specific wind speeds and sea conditions. Beachgoers and anyone planning to venture out in a kayak, canoe, sailboat, or powerboat should heed these signals. The signal flags are posted on all public beaches, and warnings are announced on TV and radio weather broadcasts, as well as on cable TV’s Weather Channel and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) broadcast network.

In the course of a single day at Acadia National Park—where more than two dozen mountains meet the sea—the casual visitor can pass through a landscape that lends itself to a surprising diversity of animal and plant life. On one outing, you can explore the shoreline—barnacles encrust the rocks, and black crowberry, an arctic shrub that finds Maine’s coastal climate agreeable, grows close to the ground alongside trails. On the same outing, you can wander beneath the boughs of the leafy hardwood forest that favors more southern climes, as well as the spruce-fir forest of the north. A little farther up the trail are subalpine plants more typically associated with mountain environments and neotropical songbirds providing background music.

Acadia’s creatures and plants will endlessly intrigue any nature lover; the following are but a sampling of what you might encounter during a visit.

Acadia National Park is surrounded by the sea—from the rockbound Schoodic Peninsula jutting from the mainland Down East to the offshore island in Penobscot Bay that Samuel de Champlain named Isle au Haut. While the park’s boundaries do not extend out to sea, the life that can be found there draws travelers and scientists alike.

The Maine coastline falls within the Gulf of Maine, a “sea within a sea” that extends from Nova Scotia to Cape Cod and out to the fishing grounds of Brown and Georges Banks. It is one of the most biologically rich environments in the world. Surface water, driven by currents off Nova Scotia, swirls in counterclockwise circles, delivering nutrients and food to the plants and animals that live there. Floating microplants, tiny shrimplike creatures, and jellyfish benefit from those nutrients and once supported huge populations of groundfish, now depleted by overfishing.

These highly productive waters lure not only fishing vessels but also sea mammals. Whales may rarely swim into the inshore bays and inlets bounded by Acadia, but whale-watching cruises based on Mount Desert Island ferry passengers miles offshore to the locales where whales gather. Whales fall into two groups: toothed and baleen. Toothed whales hunt individual prey, such as squid, fish, and the occasional seabird; they include porpoises and dolphins, killer whales, sperm whales, and pilot whales. Baleen whales have no teeth, so they must sift food through horny plates called baleen; they include finback whales, minke whales, humpback whales, and right whales. Any of these species may be observed in the Gulf of Maine.

Harbor porpoises, which grow to a length of six feet, can be spotted from a boat in the inshore waters around Mount Desert Island, traveling in pods as they hunt schools of herring and mackerel. The most you’ll usually see of them are their gray backs and triangular dorsal fins as they perform their graceful ballet through the waves.

Of great delight to wildlife watchers is catching glimpses of harbor seals. While the shores of Mount Desert Island are too busy with human activity for seals to linger, they are usually spotted during nature cruises that head out to the well-known “seal ledges.” Check the tide chart and book an excursion for low tide. Seals haul themselves out of the ocean at low tide to rest on the rocks and sunbathe. Naps are a necessity for harbor seals, which have less blubber and fur to insulate them from the frigid waters of the Gulf of Maine than other seal species. Hauling out preserves energy otherwise spent heating the body, and it replenishes their blood with oxygen.

The best time to sight seals basking on rocks and ledges is at low tide.

At high tide, you might see individual “puppy dog” faces bobbing among the waves as the seals forage for food. Harbor seals, sometimes called “sea dogs,” almost disappeared along the coast of Maine in the early 20th century. It was believed they competed with fishermen for the much-prized lobster and other valuable catches, and they were hunted nearly into oblivion. When it became obvious that the absence of seals did not improve fish stocks, the bounty placed on them was lifted. The Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 made it illegal to hunt or harm any marine mammal, except by permit—happily, populations of harbor seals now have rebounded all along the coast.

Every now and then, park rangers receive reports of “abandoned” seal pups along Acadia’s shore. Usually it’s not a stranded youngster, but rather a pup left to rest while its mother hunts for food. If you discover a seal pup on the shore, leave it undisturbed and report the sighting to rangers.

Whether walking the shore or cruising on a boat, there is no symbol so closely associated with the coast as the ubiquitous gull. Several species of gulls frequent Acadia’s skies, but none is more common than the herring gull. Easily dismissed as brassy sandwich thieves (which, of course, they are), herring gulls almost vanished in the 20th century as a result of hunting and egg collecting. Indeed, many seabird populations declined in the early 1900s due to the demand for feathers to adorn ladies’ hats. Conservation measures have helped some of these bird species recover, including the large, gray-backed herring gull, an elegant flyer that often lobs sea urchins onto the rocky shore from aloft to crack them open for the morsels within.

Common eider duck females, a mottled brown, and the black-and-white males, nicknamed “floating skunks,” congregate in large “rafts” on the icy ocean during the winter to mate. When spring arrives, males and females separate. While the males provide no help in raising the young, the females cooperate with one another, often gathering ducklings together to protect them from predators. Adult eiders may live and breed for 20 years or more, though the mortality rate is high among the young. Present along Acadia’s shore all year long, they feed on mussels, clams, and dog whelks, their powerful gizzards grinding down shells and all.

A smaller seabird regularly espied around Acadia is the black guillemot, also known as the “sea pigeon” and “underwater flyer” because it seems to fly through the water. Guillemots learn to swim before they learn to fly. Black-and-white with bright red feet, guillemots are cousins to puffins. They nest on rock ledges along the shore, laying pear-shaped eggs that won’t roll over the edge and into the waves below.

Bald eagles and ospreys (also known as fish hawks) take advantage of the fishing available in Acadia’s waters. Both of these majestic raptors suffered from the effects of the pesticide DDT, which washed down through waterways and into the ocean, becoming concentrated in the fish the raptors consumed. As a result, they laid thin-shelled eggs that broke easily, preventing the development of young. The banning of DDT in the United States has resulted in a strong comeback for both species and the removal of the bald eagle from the federal endangered species list. Along the coast of Maine, however, the bald eagle’s return has been less triumphant than in other parts of the country. Biologists continue to seek explanations for the lag, and the bald eagle remains on state and federal lists as a threatened species.

Boat cruises, some with park rangers aboard, depart from several Mount Desert Island harbors and offer good chances for sightings. They allow passengers to approach (but not too closely) nesting islands of eagles and ospreys. Both species create large nests of sticks from which they can command a wide view of the surrounding area. Some osprey nests have been documented as being 100 years old, and researchers have found everything from fishing tackle to swim trunks entwined in the sticks of the nests.

Look also for eagles and ospreys flying above inland areas of the park. Ospreys hunt over freshwater ponds and lakes, hovering until a fish is sighted, then plummeting from the sky into the water to grab the prey. For aerodynamic reasons, they carry the fish headfirst.

Acadia visitors often ask rangers if there are sea otters in the park. After all, there is an Otter Creek, which flows into Otter Cove, which is bounded by Otter Cliffs. At one time, Gorham Mountain was known as Peak of Otter! With all these place-names devoted to the otter, it would be logical to assume that Mount Desert Island teems with them. In fact, though, there are no sea otters along the entire Eastern Seaboard of the United States—perhaps the earliest European settlers mistook sea minks (now extinct) for sea otters. River otters do reside in the park, but they are reclusive and spend most of their time in freshwater environments. You might observe one during the winter frolicking on a frozen pond.

Some of the most alien creatures on earth live where the ocean washes the rocky shoreline. The creatures of this intertidal zone are at once resilient and fragile, and always fascinating. Some of the creatures and plants live best in the upper reaches of the intertidal zone, which is doused only by the spray of waves and the occasional extra-high tide. Others, which would not survive the upper regions, thrive in the lower portion of the intertidal zone, which is almost always submerged. The rest live in rocky pockets of water in between, and all are influenced by the ebb and flow of the tide. Temperature, salinity, and the strength of crashing waves all determine where a creature will live in the intertidal zone.

As you approach the ocean’s edge, the first creatures likely to come underfoot are barnacles—vast stretches of rock can be encrusted with them. Step gently, for walking on barnacles crushes them. Their tiny, white, volcano-shaped shells remain closed when exposed to the air, but they open to feed when submerged. Water movement encourages them to sweep the water with feathery “legs” to feed on microscopic plankton.

Despite the tough armor with which barnacles cover themselves, they are preyed on by dog whelks (snails), which drill through the barnacle shells with their tongues to feed on the creature within. A dog whelk can be distinguished from the common periwinkle by the elliptical opening of its shell. Periwinkles have teardrop-shaped openings.

Sea stars find blue mussels yummy. Blue mussels siphon plankton from the water and anchor themselves in place with byssus threads. Sea stars creep up on the mussels, wrap their legs around them, and pry open their shells just enough to insert their stomachs and consume the animal inside. Look for sea stars and mussels in the lower regions of tide pools.

Related to sea stars are sea urchins—spiky green balls most often seen as empty, spineless husks littered along the shoreline (they are frequently preyed on by gulls). If you come upon a live sea urchin, handle it with care. While their spikes are not poisonous, they are sharp. Gently roll a sea urchin over to see its mouth and the five white teeth with which it gnaws on seaweed and animal remains. (While the green sea urchins found in Acadia do not possess poisonous spines, some of their counterparts in other regions do.)

Limpets, with cone-shaped shells, are snails that rely on seaweed for food. They suction themselves to rocks, which prevents them from drying up when exposed at low tide. Do not tear limpets from rocks—doing so hurts the animal.

Many intertidal creatures depend on seaweed for protection and food. Rockweeds drape over rocks, floating with the waves, their long fronds buoyed by distinctive air bladders. Dulse (edible for people) is common along the shore, as is Irish moss, used as a thickener in ice cream, paint, and other products.

The best way to learn about the fascinating world that exists between the tides is to look for creatures in their own habitats, with a good field guide as a reference.

• Go at low tide—there are two low tides daily, 12 hours apart.

• Tread carefully. Shoreline rocks are slippery.

• Do not remove creatures from their habitats; doing so could harm them.

• Be aware of the ocean at all times. Sudden waves can wash the shore and sweep you to your death.

• Join a ranger-guided shoreline walk to learn more about this unique environment. Check the Beaver Log, Acadia’s official park newspaper, for the schedule and details.

Known best for its rocky shoreline and mountains, Acadia National Park cradles numerous glistening lakes and ponds in its glacially carved valleys. Several lakes serve as public water supplies for surrounding communities, and swimming is prohibited in most. Echo Lake and the north end of Long Pond are excellent designated swimming areas. Freshwater fishing requires a state license for adults. Obey the posted regulations.

The voice of the northern wilderness belongs to the common loon, whose roots are so ancient it is the oldest bird species found in North America. During the summer months, loons are garbed in striking white-and-black plumage, which fades to gray during the winter when they migrate to the ocean’s open waters. Graceful swimmers, loons are clumsy on land. Their webbed feet are set to the rear of their bodies, making them front-heavy. Land travel is a struggle. Consequently, they nest very close to the water’s edge, which makes them vulnerable to such human hazards as the wakes of motorized watercraft.

The loon’s mysterious ululating call can be heard echoing across lakes on most any summer evening, an eerie sound not quickly forgotten.

Evening is actually an excellent time to observe wildlife. Creatures that seem shy and reclusive by day tend to be most active at dawn and dusk (crepuscular) or at night (nocturnal). Carriage roads along Eagle Lake, Bubble Pond, and Witch Hole Pond make nighttime walking easy. (Hint: Go at dusk so your eyes adjust with the darkening sky, and keep in mind that abrupt flashlight use ruins night vision.)

Frog choruses form the backdrop to the cries of loons. In Acadia, there are eight frog and toad species, which tend to be most vocal during the spring mating season. Close your eyes and listen to see if you can distinguish individual species, such as the “banjo-twanging” croak of the green frog and the “snore” of the leopard frog.

The onset of moonlight may reveal small winged creatures swooping, darting, and careening over lakes and ponds. Acadia is home to several species of bats, including the common little brown bat. Don’t scream! Bats have no desire to get entangled in your hair. Their echolocation (radar) is so fine-tuned that it can detect a single strand of human hair. Bats are far more interested in the mosquitoes attracted to your body heat. True insect-munching machines, a single pinky-size little brown bat can eat hundreds, if not thousands, of insects in one evening.

Bandit-faced raccoons are also creatures of the night, and they sometimes can be found scampering along the shore. They are omnivorous, dining on anything from grubs, frogs, and small mammals to fish, berries, and garbage. Rabies is present in Maine, and raccoons are common carriers of the disease. Do not approach sick-acting animals (seeing them during the daytime may indicate illness), and report any strange behavior to a park ranger. When camping or picnicking, stow food items in your vehicle and dispose of scraps properly. Raccoons are opportunistic thieves that have been known to claw their way into tents to find food.

And where are the moose? The question is asked often at Acadia’s visitors center, and wildlife-watchers are disappointed to learn that moose, the largest members of the deer family, are rarely sighted in the park. Moose are more frequently observed in western and northern Maine, in the Moosehead Lake and Baxter State Park regions. However, individuals are spotted from time to time on Mount Desert Island, and there may even be a small family group residing on the west side. Moose like to dine on aquatic vegetation, such as the tubers of cattails and lily pads, and they frequent marshes and lakes to escape biting flies. Bass Harbor Marsh is an inviting habitat for moose, but good luck spotting one.

A prehistoric-looking creature sometimes encountered on carriage roads near ponds is the snapping turtle. An average adult may weigh 30 pounds or more. Keep well clear of the snapper’s powerful beak, which is lightning-quick when grabbing prey; it can do real damage, such as biting off fingers. Adult snappers have no predators (except people), and they will dine on other turtles, frogs, ducklings, wading birds, and beaver kits.

By midsummer, many of Acadia’s ponds are beautifully adorned with yellow water lilies and white pond lilies. Lily pads are a favorite food of beavers, which emerge from their lodges—large piles of sticks and mud—at dusk and dawn to feed and make necessary repairs to their dams. Beavers create their own habitat by transforming streams into ponds. They move awkwardly on land, so they adjust the water level close to their source of building materials and other favored foods: aspen and birch trees. Doing so limits their exposure to dry land and predators.

Beavers are large rodents that were trapped excessively for centuries for the fur trade. They have since made a strong comeback in Acadia—to the point that their ponds now threaten roads, trails, and other park structures. Resource managers try to keep ahead of the beavers by inserting “beaver foolers” (PVC pipes) through dams that block road culverts. This moderates pond levels and prevents damage to roads by allowing water to drain through the culvert. Sometimes the beavers, however, get ahead of the resource managers. They have been known to plug the beaver foolers with sticks and mud, or to chew through them with their strong teeth.

Amazingly adapted for life in the water, beavers are fascinating to watch. A very accessible location along the Park Loop Road, just past Bear Brook Picnic Area, is Beaver Dam Pond, featuring a few lodges, a dam, and an active beaver population. The best viewing times are dawn and dusk. In the fall the beavers are busiest, preparing food stores for the winter to come. The park often presents a beaver-watch program at that time of year, which is a great way to learn more about the habits and adaptations of the beaver.

Beavers act as a catalyst for increasing natural diversity in an area. Their ponds attract ospreys, herons, and owls; salamanders, frogs, and turtles; insects and aquatic plants; foxes, deer, muskrats, and river otters. Their ponds help maintain the water table, enrich soils, and prevent flooding.

While beavers may bring diversity to a wetland, an invader has been endangering Acadia’s ponds and lakes. Purple loosestrife, a showy stalked purple flower not native to North America, was introduced into gardens as an ornamental. Highly reproductive and adaptive and with no natural predators, purple loosestrife escaped the confines of gardens and has literally choked the life out of some wetlands by crowding out native plants on which many creatures depend, thus creating a monoculture. Few native species find purple loosestrife useful.

Purple loosestrife has been contained at Acadia, but it’s an ongoing process. Uprooting it seems to encourage more to grow, and jostling stalks at certain times of the year disperses vast numbers of seeds, so resource managers have resorted to treating individual plants with an approved herbicide in a way that does not harm the surrounding environment.

A dark, statuesque spruce-fir forest dominates much of Acadia’s woodlands and does well in the cooler, moist environs of Maine’s coast. Red spruce trees are tall and pole-like and often cohabit with fragrant balsam fir. The spruce grows needles only at the canopy, sparing little energy for growing needles where the sun cannot reach. Because the sun barely touches the forest floor, little undergrowth emerges from the bump and swale of acidic, rust-colored needles that carpet the ground, except for more tiny, shade-loving spruce, waiting for their chance to grow tall.

The spruce-fir forest can be uncannily quiet, especially in the middle of the day. The density of the woods and the springy, needle-laden floor seem to buffer noise from without. Listen closely, however, and you may hear the cackle of ravens, the squabble of a territorial red squirrel, or the rat-a-tat of a woodpecker.

Red squirrels are energetic denizens of the spruce-fir forest, scolding innocent passersby or sitting on tree stumps scaling spruce cones and stuffing their cheeks full of seeds. Observant wildlife watchers will find their middens (heaps of cone scales) about the forest. Squirrels are especially industrious (even comical) in autumn as they frantically prepare for the winter by stocking up on food, tearing about from branch to branch with spruce cones poking out of their mouths like big cigars.

Woodpeckers favor dead, still-standing trees, shredding the bark to get at the insects infesting the trunk. The pileated woodpecker—a large black-and-white bird with a red cap—is relatively shy, so you are more likely to encounter evidence of its passage (rectangular and oval holes in trees) than the bird itself. Other common species you might observe are the hairy and the downy woodpecker.

The face of Acadia’s woodlands changed dramatically in 1947. That fall, during a period of extremely dry conditions, a fire began west of the park’s present-day visitors center in Hulls Cove. Feeding on tinder-dry woods and grasses, and whipped into an inferno by gale-force winds, the fire roared across the eastern half of Mount Desert Island, miraculously skirting downtown Bar Harbor but destroying numerous year-round and seasonal homes. In all, 17,000 acres burned, 10,000 of them in the park.

Deer are common on Mount Desert Island.

Researchers have studied 6,000 years of the park’s fire history by pulling core samples from ponds to analyze the layers of pollen and charcoal that have settled in their bottoms over time. The charcoal indicates periods of fire, and the most significant layer of charcoal appeared in the period around 1947, indicating the intensity of the great fire.

The aftermath of the fire—the scorched mountainsides and skeletal, blackened remains of trees—must have been a devastating sight. Loggers salvaged usable timber and removed unsafe snags. Seed was ordered so replanting could begin in earnest. Soils needed to be stabilized and the landscape restored.

Then a curious thing happened the following spring: As the snow melted, green shoots began to poke up out of the soil among the sooty remains. “Pioneer plants,” such as low-bush blueberry and Indian paintbrush, took over the job of stabilizing the soil. By the time the ordered seeds arrived two years later (demand had been overwhelming, for much of Maine had burned in 1947), nature was already mending the landscape without human intervention. What had been blackened showed promise and renewal in green growing things.

Over the decades since then, a mixed deciduous forest has grown up from the ashes of the fire, supplanting the dominance of the spruce-fir forest on Mount Desert Island’s east side. Birch, aspen, maple, oak, and beech have embraced wide-open sunny places where shady spruce once thrived. The new growth not only added colorful splendor to the autumn landscape but also diversified the wildlife.

Populations of white-tailed deer benefited from all the new browse (and a lack of major predators), and by the 1960s, the island’s deer herd had soared in numbers. Recent studies have shown the population to be healthy and stable—perhaps due to car-deer collisions and predation from the recently arrived eastern coyote.

Coyotes crossed the Trenton Bridge and wandered onto Mount Desert Island in the 1980s. They had been expanding their territory throughout the northeast, handily picking up the slack in the food chain caused when other large predators, such as the northern gray wolf and the lynx, were hunted and trapped out of the state. While coyote sightings do occur, you are more likely to be serenaded by yipping and howling in the night. Their vocalizations warn off other coyotes, or let them keep in touch with the members of their packs.

The snowshoe hare, or varying hare, is a main prey species of the coyote. The large hind feet of these mammals allow them to stay aloft in the snow and speed away from predators. Camouflage also aids these fleet-footed hares—their fur turns white during the winter and brown during the summer, hence the name varying hare. Not all hares escape their predators. It is not uncommon to encounter coyote scat full of hare fur along a carriage road or trail.

Also along a carriage road or trail, you might encounter a snake sunning itself on a rock. Five species of snakes—including the garter snake, milk snake, and green snake—inhabit Acadia. None of these snakes are poisonous, but they will bite if provoked.

While autumn may cloak Acadia’s mountainsides in bright beauty, spring and summer bring relief to Mainers weary of ice storms, shoveling, freezing temperatures, and short, dark days. Spring arrives with snowy clusters of star flowers along roadsides, and white mats of bunchberry flowers (dwarf members of the dogwood family) on the forest floor. Birdsong provides a musical backdrop. Twenty-one species of wood warblers migrate to Acadia from South America to nest—among them are the American redstart, ovenbird, yellow warbler, and Blackburnian warbler. At the visitors center, request a bird checklist, which names 273 species of birds that have been identified on Mount Desert Island and adjacent areas. Then join a ranger for an early-morning bird walk. Check the Beaver Log for details.

The fire of 1947 may have transformed a portion of Acadia’s woodlands, but change is always part of a natural system. While the broad-leafed trees that grew up in the wake of the fire continue to grow and shed leaves as the cycle of nature demands, young spruce trees poke up through duff and leaf litter, waiting in the shade for their chance to dominate the landscape once again.

A hike up one of Acadia’s granite-domed mountains will allow you to gaze down at the world with a new perspective. Left behind is the confining forest—the woods, in fact, seem to shrink as you climb. On the south-facing slopes of some mountains, you’ll encounter squat and gnarled pitch pines. The fire of 1947 not only was beneficial to the growth of deciduous vegetation, but it also aided in the regeneration of pitch pines, which rely on heat, such as that generated by an intense fire, to open their cones and disperse seeds.

Wreathing rocky outcrops and the sides of trails are such shrubs as low-bush blueberry, sheep laurel (lambkill), and bayberry. In the fall, their leaves turn blood-red. In the spring, shadbush softens granite mountainsides with white blossoms.

Green and gray lichens plaster exposed rocks in patterns like targets. Composed of algae and fungi, lichens were probably among the first organisms to grow in Acadia as the vast ice sheets retreated 10,000-20,000 years ago. Sensitive to air pollution and acid rain, lichens have become barometers of air quality all over the world.

On mountain summits, the trees are stunted. These are not necessarily young trees—some may be nearly 100 years old. The tough, cold, windy climate and exposed conditions of summits force plantlife to adapt to survive. Growing close to the ground to avoid fierce winds is one way in which trees have adapted to life at the summit.

Other plants huddle in the shallow, gravelly soil behind solitary rocks, such as three-toothed cinquefoil, a member of the rose family that produces a tiny white flower in June-July, and mountain sandwort, which blooms in clusters June-September.

While adapted to surviving the extreme conditions of mountain summits, plants can be irreparably damaged by feet trampling off-trail or by removal of rocks to add to cairns (trail markers) or stone “art.” One has only to look at the summit area of Cadillac Mountain to see the damage wrought by millions of roving feet: the missing vegetation and the eroded soils. It may take 50-100 years for some plantlife, if protected, to recover. Some endangered plant species that grow only at summits may have already disappeared from Cadillac due to trampling.

To protect mountain summits and to preserve the natural scene, follow Leave No Trace principles of staying on the trail and on durable surfaces, such as solid granite. Do not add to cairns or build rock art, a form of graffiti that not only damages plants and soils but also blemishes the scenery for other visitors.

Autumn provides a terrific opportunity to observe raptors of all kinds. In the fall, during their south migration, raptors take advantage of northwest winds flowing over Acadia’s mountains. Eagles, red-tailed hawks, sharp-shinned hawks, goshawks, American kestrels, peregrine falcons, and others can be spotted. The peregrine, a seasonal mountain dweller, has been reintroduced to Acadia after a long absence. Late August-mid-October, join park staff for the annual hawk watch atop Cadillac Mountain (weather permitting) to view and identify raptors. In a typical year, hawk-watchers count an average of 2,500 raptors from 10 species. The most prevalent species are American kestrels and sharp-shinned hawks.

• Seek out wildlife at dusk and dawn when it is more active. Bring binoculars and a field guide.

• Leave Rover at home—pets are intruders into the natural world, and they will scare off wildlife. If leaving your dog behind is not an option, remember that in the park, pets must be restrained on a leash no longer than six feet. This is for the safety of both the pet and wildlife, and it is courteous to other visitors.

• Never approach wildlife, which could become aggressive if sick or feeling threatened. Enjoy wildlife at a distance.

• Do not feed wildlife, not even gulls. Feeding turns wild animals into aggressive beggars that lose the ability to forage for themselves, and it often ends in their demise.

• Join walks, talks, hikes, cruises, and evening programs presented by park rangers to learn more about the national park and its flora and fauna. Programs are listed in the Beaver Log, readily available at the Hulls Cove Visitors Center, the Acadia Nature Center, and park campgrounds, as well as online (www.nps.gov/acad).

• Visit the nature center at Sieur de Monts Spring, where exhibits show the diversity of flora and fauna in the park and the challenges that resource managers face in protecting it.

(The Plants and Animals section of this chapter was written by Kristen Britain, former writer and editor for Acadia National Park.)

You’ve already read about some of Acadia’s major environmental issues, but still others exist. Tops among these are air pollution and overcrowding. Of utmost importance is the matter of “zero impact,” addressed by the Leave No Trace philosophy actively practiced at Acadia.

In 2002, a study by the private National Parks Conservation Association revealed that Acadia National Park had the fifth-worst air quality of all the national parks; Acadia allegedly has twice as much haze as the Grand Canyon. Most scientists and environmentalists attribute the problem primarily to smoke and haze from power plants in the Midwest and the South. New England is the end of the line, so to speak, for airborne pollutants, and it’s estimated that 80 percent of Maine’s pollution arrives from other regions. Maine has the highest asthma rate in the nation, rivers and lakes have high concentrations of mercury, and rainfall at Acadia is notably acidic. Maine’s four federal legislators and others in the region have been especially active in their efforts to strengthen the Clean Air Act and improve conditions at Acadia and in the rest of New England.

To heighten public awareness of pollution problems, a new public-private joint program has initiated CAMNET, an intriguing monitoring system that provides real-time pollution and visibility monitoring. Acadia is one of the nine New England sites with cameras updating images every 15 minutes. Log on to www.hazecam.net for data on current temperature and humidity, wind speed and direction, precipitation totals, visual range, and the air-pollution level (low, medium, or high). The site also includes a selection of photos showing the variations that have occurred in the past at Acadia. In the “clear day” photo, visibility was pegged at 199 miles! Ozone alerts, according to Environmental Protection Agency standards, usually occur at Acadia a couple of times each summer. When they do, rangers put out signs to caution visitors—particularly hikers and bikers—to restrict strenuous activity.

While pollution is an Acadia issue—affecting the park, its vegetation and wildlife, and its visitors—the solution must be a national one. Stay tuned.

With more than three million visitors in 2016, Acadia and National Park Service officials are wrestling with a question: How many people are too many people? Other national parks have initiated visitor limitations, and Acadia is currently working on a transportation plan that may limit some access by private vehicles. That plan, to be unveiled in 2018, likely will take at least a year or two to implement.

The establishment of the propane-powered Island Explorer bus service has greatly alleviated traffic (and thus also auto, SUV, and RV emissions) during the months it operates (late June-early October), but its popularity is growing more quickly than its capacity. Although efforts to identify peak routes and times and add extra service are being made, there’s still a chance you may have to wait a bit.

Cruise-vessel visits in Bar Harbor have multiplied exponentially in recent years, and now plans are under consideration to create a major cruise dock just south of the town. Most passengers spend at least some time in the park, but it’s a minimal amount of time—often just a carriage ride or a visit to Jordan Pond House or the Cadillac summit. (Bar Harbor merchants, of course, welcome the influx.)

The heaviest use of the park occurs in July-August, with marginally less use in September and early October, yet there are still quiet corners of the park; it’s a matter of finding them: Head over to the Quiet Side, get out to the islands, hike less utilized trails or explore more remote carriage roads. The best advice, if possible, is to visit in shoulder seasons—May-June and mid- to late October. You take your chances then with weather and temperatures, and some sights and businesses might not be open, but if you’re flexible and adaptable, it could be the best vacation you’ve ever had.

As the great continental glacier receded out of Maine to the northwest about 11,000 years ago, some prehistoric grapevine must have alerted small bands of hunter-gatherers—fur-clad Paleo-Indians—to the scrub sprouting in the tundra, burgeoning mammal populations, and the ocean’s bountiful food supply. They came to the shore in droves—at first seasonally, then year-round. Anyone who thinks tourism is a recent phenomenon in this part of Maine need only explore the shoreline of Mount Desert Island, where cast-off oyster shells and clamshells document the migration of early Native Americans from woodlands to waterfront. “The shore” has been a summertime magnet for millennia.

Archaeological evidence from the Archaic period in Maine—roughly 8000-1000 BC—is fairly scant, but paleontologists have unearthed stone tools and weapons and small campsites attesting to a nomadic lifestyle supported by fishing and hunting, with fishing becoming more extensive as time went on. Toward the end of the tradition, during the late Archaic period, there emerged a rather anomalous Indian culture known officially as the Moorehead phase but informally called the Red Paint People; the name comes from their curious trait of using a distinctive red ocher (pulverized hematite) in burials. Dark red puddles and stone artifacts have led excavators to burial pits in Ellsworth and Hancock. Just as mysteriously as they had arrived, the Red Paint People disappeared abruptly and inexplicably around 1800 BC.

Following them almost immediately—and almost as suddenly—hunter-gatherers of the Susquehanna Tradition arrived from well to the south, moved across Maine’s interior as far as the St. John River, and remained until about 1600 BC, when they too enigmatically vanished. Excavations have turned up relatively sophisticated stone tools and evidence that they cremated their dead. It was nearly 1,000 years before a major new cultural phase appeared.

The next great leap forward was marked by the advent of pottery making, introduced about 700 BC. The Ceramic period stretched to the 16th century, and cone-shaped pots (initially stamped, later incised with coiled-rope motifs) survived until the introduction of metals from Europe. During this time, at Pemetic (their name for Mount Desert Island) and on some of the offshore islands, Native American fisherfolk and their families built houses of sorts—seasonal, wigwam-style birchbark dwellings—and spent the summers fishing, clamming, trapping, and making baskets and functional birchbark objects.

The identity of the first Europeans to set foot in Maine is a matter of debate. Historians dispute the romantically popular notion that Norse explorers checked out this part of the New World as early as AD 1000. Even an 11th-century Norse coin found in 1961 in Brooklin, near Blue Hill, west of Mount Desert Island, was probably carried there from farther northeast.

Not until the late 15th century, the onset of the great Age of Discovery, did credible reports of the New World, including what is now Maine, filter back to Europe’s courts and universities. Thanks to innovations in naval architecture, shipbuilding, and navigation, astonishingly courageous fellows crossed the Atlantic in search of rumored treasure and new routes for reaching it.

John Cabot, sailing from England aboard the ship Mathew, may have been the first European to reach Maine, in 1498, but historians have never confirmed a landing site. There is no question, however, about the account of Giovanni da Verrazzano, a Florentine explorer commanding La Dauphine under the French flag, who reached the Maine coast in 1524. Encountering less-than-friendly Native Americans, Verrazzano did a minimum of business and sailed onward toward Nova Scotia. Four years later, he died in the West Indies. His brother’s map of their landing site (probably on the Phippsburg Peninsula, near Bath) labels it “The Land of Bad People.” Esteban Gómez, a Portuguese explorer sailing under the Spanish flag, followed in Verrazzano’s wake in 1525, but the only outcome of his exploits was an uncounted number of captives whom he sold into slavery in Spain. A map created several years later from Gómez’s descriptions seems to indicate he had at least glimpsed Mount Desert Island.

More than half a century passed before the Maine coast turned up again on European explorers’ itineraries. This time, interest was fueled by reports of a Brigadoon-like area called Norumbega (or Oranbega, as one map had it), a myth that arose, gathered steam, and took on a life of its own in the decades following Verrazzano’s voyage.

By the 17th century, when Europeans began arriving in more than twos and threes and getting serious about colonization, Native American agriculture was already under way, the cod fishery was thriving on offshore islands, Native Americans far to the north were hot to trade furs for European goodies, and the birchbark canoe was the transport of choice when the Penobscots headed down Maine’s rivers toward their summer sojourns on the coast.

In the early 17th century, English dominance of exploration west of the Penobscot River (roughly from present-day Bucksport down to the New Hampshire border and beyond) coincided roughly with increasing French activity east of the river—including Mount Desert Island and the nearby mainland.

In 1604, French nobleman Pierre du Gua, Sieur de Monts, bearing a vast land grant for “La Cadie” (Acadia) from King Henry IV, set out with cartographer Samuel de Champlain to map the coastline. They first reached Nova Scotia’s Bay of Fundy and then sailed up the St. Croix River. Mid-river, just west of present-day Calais, a crew planted gardens and erected buildings on today’s St. Croix Island while du Gua and Champlain went off exploring. The two men and their crew sailed up the Penobscot River to present-day Bangor, searching fruitlessly for Norumbega, and next “discovered” the imposing island Champlain named l’Îsle des Monts Déserts because of its treeless summits. Here they entered Frenchman Bay, landed at today’s Otter Creek in early September, and explored inlets and bays in the vicinity before returning to St. Croix Island to face the elements with their ill-fated compatriots. Scurvy, lack of fuel and water, and a ferocious winter wiped out nearly half of the 79 men in the St. Croix settlement. In spring 1605, du Gua, Champlain, and other survivors headed southwest again, exploring the coastline all the way to Cape Cod before returning northeast and settling permanently at Nova Scotia’s Port Royal (now Annapolis Royal).

Eight years later, French Jesuit missionaries en route to the Kennebec River (or, as some allege, seeking Norumbega) ended up on Mount Desert Island. With a band of about three dozen French laymen, they set about establishing the St. Sauveur mission settlement at present-day Fernald Point. Despite the welcoming presence of amiable Native Americans (led by Asticou, an eminent Penobscot sagamore), leadership squabbles led to building delays, and English marauder Samuel Argall—assigned to reclaim this territory for England—arrived in his warship Treasurer to find them easy prey. The colony was leveled, the settlers were set adrift in small boats, the priests were carted off to the Jamestown colony in Virginia, and Argall moved on to destroy Port Royal.

Even though England yearned to control the entire Maine coastline, her turf, realistically, remained south and west of the Penobscot River. During the 17th century, the French had expanded from their Canadian colony of Acadia. Unlike the absentee bosses who controlled the English territory, French merchants actually showed up, forming good relationships with the Native Americans and cornering the market in fishing, lumbering, and fur trading. And French Jesuit priests converted many Native Americans to Catholicism. Intermittently, overlapping Anglo-French land claims sparked messy local conflicts.

In the mid-17th century, the strategic heart of French administration and activity in Maine was Fort Pentagoet, a sturdy stone outpost built in 1635 in what is now Castine, on the peninsula west of Mount Desert Island. From Pentagoet, the French controlled coastal trade between the St. George River and Mount Desert Island and well up the Penobscot River. In 1654, England captured and occupied Pentagoet and much of French Acadia, but thanks to the 1667 Treaty of Breda, title returned to the French in 1670, and Pentagoet briefly became Acadia’s capital.

A short but nasty Dutch foray against Acadia in 1674 resulted in Pentagoet’s destruction (“levell’d with ye ground,” by one account) and the raising of yet a third national flag over Castine.

From the late 17th to the late 18th centuries, half a dozen skirmishes along the coast—often sparked by conflicts in Europe—preoccupied the Wabanaki (Native American groups), the French, and the English. In 1759, roughly midway through the Seven Years’ War, the British came out on top in Quebec, allowing Massachusetts governor John Bernard to divvy up the acreage on Mount Desert Island. Two brave pioneers—James Richardson and Abraham Somes—arrived with their families in 1760, and today’s village of Somesville marks their settlement. Even as the American Revolution consumed the colonies, Mount Desert Island maintained a relatively low profile, politically speaking, into the early 19th century. A steady stream of homesteaders, drawn by the appeal of free land, sustained their families by fishing, farming, lumbering, and shipbuilding. On March 15, 1820, the District of Maine, which included Mount Desert Island, broke from Massachusetts to become the 23rd state in the Union, with its capital in Portland (the capital moved to Augusta in 1832).

Around the middle of the 19th century, explorers of a different sort arrived on Mount Desert Island. Seeking dramatic landscapes rather than fertile land, painters of the acclaimed Hudson River School found more than enough inspiration for their canvases. Thomas Cole (1801-1848), founder of the group, visited Mount Desert only once, in 1844, but his onetime student Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900) vacationed here in 1850 and became a summer resident two decades later. Once dubbed “the Michelangelo of landscape art,” Church traveled widely in search of exotic settings for his grand landscapes. After his summers on Mount Desert, he spent his final days at Olana, a Persian-inspired mansion overlooking the Hudson River.

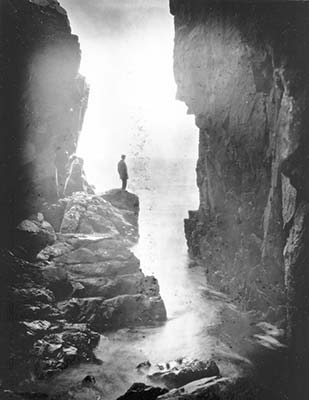

early rusticator at Little Hunters Beach

It’s no coincidence that artists formed a large part of the 19th-century vanguard here: The dramatic landscape, with both bare and wooded mountains descending to the sea, still inspires those who see it. Those pioneering artists brilliantly portrayed this area, adding a few romantic touches to landscapes that really need no enhancement. Known collectively as “rusticators,” the artists and their coterie seemed content to “live like the locals” and rented basic rooms from island fisherfolk and boatbuilders. But once the word got out and painterly images began confirming the reports, the surge of visitors began—particularly after the Civil War, which had so totally preoccupied the nation. Tourist boardinghouses appeared first, followed by sprawling hotels—by the late 1880s, there were nearly 40 hotels on the island, luring vacationers for summerlong stays.

At about the same time, the East Coast’s corporate tycoons zeroed in on Mount Desert, arriving by luxurious steam yachts and building over-the-top grand estates (quaintly called “summer cottages”) along the shore north of Bar Harbor. Before long, demand exceeded acreage, and mansions also began appearing in Northeast and Southwest Harbors. Their seasonal social circuit was a catalog of rich and famous families—Rockefeller, Astor, Vanderbilt, Ford, Whitney, Schieffelin, Morgan, and Carnegie, just for a start. Also part of the elegant mix were noted academics, doctors, lawyers, and even international diplomats. The “Gay Nineties” earned their name on Mount Desert Island.

Fortunately for Mount Desert—and, let’s face it, for all of us—many of the rusticators maintained a strong sense of noblesse oblige, engaging regularly in philanthropic activity. Notable among them was George Bucknam Dorr (1853-1944), who spent more than 40 years fighting to preserve land on Mount Desert Island and ultimately earned the title “Father of Acadia.”

George Dorr, the Father of Acadia

As Dorr related in his memoir, the saga began with the establishment of the Hancock County Trustees of Public Reservations, a nonprofit corporation modeled on the Trustees of Public Reservations in Massachusetts and chartered in early 1903 “to acquire, by devise, gift or purchase, and to own, arrange, hold, maintain or improve for public use lands in Hancock County, Maine (encompassing Mount Desert Island as well as Schoodic Point), which by reason of scenic beauty, historical interest, sanitary advantage or other like reasons may become available for such purpose.” President of the new corporation was Charles W. Eliot, president emeritus of Harvard. Dorr became the vice president and “executive officer,” and he dedicated the rest of his life to the cause.

Dorr wrote letters, cajoled, spoke at meetings, arrived on potential donors’ doorsteps, and even resorted to polite ruses as he pursued his mission. He also delved into his own pockets to subsidize land purchases. Dorr was a fund-raiser par excellence, a master of networking decades before the days of instant communications. Gradually he accumulated parcels—ponds, woodlands, summits, trails—and gradually his enthusiasm caught on. But easy it wasn’t. He faced down longtime local residents, potential developers, and other challengers, and he politely but doggedly visited grand salons, corporate offices, and the halls of Congress in his quest.

In 1913, Bar Harbor taxpayers—irked by the increasing acreage being taken off the tax rolls—prevailed on their state legislator to introduce a bill to annul the corporation’s charter. Dorr’s effective lobbying doomed the bill, but the corporation saw trouble ahead and devised a plan on a grander scale. Again thanks to Dorr’s political and social connections and intense lobbying in Washington DC, President Woodrow Wilson created the Sieur de Monts National Monument on July 8, 1916, from 5,000 acres given to the government by the Hancock County Trustees of Public Reservations. Dorr acquired the new title of Custodian of the Monument.

After the establishment of the National Park Service in August 1916, and after Sieur de Monts had received its first congressional appropriation ($10,000), Dorr forged ahead to try to convince the government to convert “his” national monument into a national park. “No” meant nothing to him. Not only did he schmooze with members of Congress, cabinet members, helpful secretaries, and even former president Theodore Roosevelt, he also provided the pen (filled with ink) and waited in the president’s outer office to be sure Wilson signed the bill. On February 26, 1919, Lafayette National Park became the first national park east of the Mississippi River; George Bucknam Dorr became its first superintendent. Ten years later, the name was changed to Acadia National Park.

Wildfires are no surprise in Maine, where woodlands often stretch to the horizon, but 1947 was unique in the history of the state and of Acadia. A rainy spring led into a dry, hot summer with almost no precipitation and then an autumn with still no rain. Wells went dry, vegetation drooped, and the inevitable occurred—a record-breaking inferno. Starting on October 17 as a small, smoldering fire at the northern end of the island, it galloped south and east, abetted by winds, and moved toward Bar Harbor and Frenchman Bay before coming under control on October 27. More than 17,000 acres burned, including more than 10,000 in Acadia National Park. Sixty-seven magnificent “cottages” were incinerated on “Millionaires’ Row,” along the shore north of Bar Harbor, with property damage of more than $20 million. Some of the mansions, incredibly, escaped the flames, but most of the estates were never rebuilt. Miraculously, only one person died in the fire. A few other deaths occurred from heart attacks and traffic accidents as hundreds of residents scrambled frantically to escape the island. Even the fisherfolk of nearby Lamoine and Winter Harbor pitched in, staging their own mini Dunkirk to evacuate more than 400 residents by boat.

If only George Dorr could see today’s Acadia, covering more than 49,000 acres on Mount Desert Island, the Schoodic Peninsula mainland, and parts of Isle au Haut, Baker Island, and Little Cranberry Island. The fire changed Mount Desert’s woodland profile—from the dark greens of spruce and fir to a mix of evergreen and deciduous trees, making the fall foliage even more dramatic than in Dorr’s day. If ever proof were needed that one person (enlisting the help of many others) can indeed make a difference, Acadia National Park provides it.

Maine’s population didn’t top the one million mark until 1970. Forty years later, according to the 2010 census, the state had 1.3 million residents.

Despite the long-standing presence of several substantial ethnic groups, plus four Native American groups that account for about 1 percent of the population, diversity is a relatively recent phenomenon in Maine, and the population is about 95 percent Caucasian. A steady influx of refugees, beginning after the Vietnam War, forced the state to address diversity issues, and it continues to do so today. While Portland is the state’s most diverse city, tiny Milbridge has a surprisingly diverse population thanks to immigrants who arrive to pick blueberries and often settle there.

People who weren’t born in Maine aren’t natives. Even people who were born here may experience close scrutiny of their credentials. In Maine, there are natives and there are natives. Every day the obituary pages describe Mainers who have barely left the houses in which they were born—even in which their grandparents were born. We’re talking roots.

Along with this kind of heritage comes a whole vocabulary all its own—lingo distinctive to Maine or at least to New England. Part of the “native” picture is the matter of native produce. Hand-lettered signs sprout everywhere during the summer advertising native corn, native peas, even—believe it or not—native ice. In Maine, homegrown is well grown.

“People from away,” on the other hand, are those whose families haven’t lived here year-round for at least a generation. But people from away (also called “flatlanders”) exist all over Maine, and they have come to stay, putting down roots of their own and altering the way the state is run, looks, and will look. You’ll find flatlanders as teachers, corporate executives, artists, retirees, writers, town selectmen, and even lobstermen.

In the 19th century, arriving flatlanders were mostly “rusticators” or “summer complaints”—summer residents who lived well, often in enclaves, and never set foot in the state off-season. They did, however, pay property taxes, contribute to causes, and provide employment for local residents. Another 19th-century wave of people from away came from the bottom of the economic ladder: Irish escaping the potato famine and French Canadians fleeing poverty in Quebec. Both groups experienced subtle and overt anti-Catholicism but rather quickly assimilated into the mainstream, taking jobs in mills and factories and becoming staunch American patriots.

The late 1960s and early 1970s brought bunches of “back-to-the-landers,” who scorned plumbing and electricity and adopted retro ways of life. Although a few pockets of diehards still exist, most have changed with the times and adopted contemporary mores (and conveniences).

Today, technocrats arrive from away with computers, smartphones, and other high-tech gear and “commute” via the Internet and modern electronics, although getting a cell phone signal is still a challenge in parts of the Acadia region.

In Maine, the real natives are the Wabanaki (People of the Dawn)—the Micmac, Maliseet, Penobscot, and Passamaquoddy of the eastern woodlands. Many live in or near three reservations, near the headquarters for their governors. The Passamaquoddies are at Pleasant Point in Perry, near Eastport, and at Indian Township in Princeton, near Calais. The Penobscots are based on Indian Island in Old Town, near Bangor. Other Native American population clusters—known as “off-reservation Indians”—are the Aroostook Band of Micmacs, based in Presque Isle, and the Houlton Band of Maliseets in Littleton, near Houlton.

In 1965, Maine became the first state to establish a Department of Indian Affairs, but just five years later the Passamaquoddy and Penobscot people initiated a 10-year-long land-claims case involving 12.5 million Maine acres—about two-thirds of the state—weaseled from their ancestors by Massachusetts in 1794. In late 1980, a landmark agreement, signed by President Jimmy Carter, awarded the tribes $80.6 million in reparations. Despite this, Native American communities still struggle to provide jobs on the reservations and to increase their overall standard of living.

One of the true Native American success stories is the revival of traditional arts as businesses. The Maine Indian Basketmakers Alliance has an active apprenticeship program, and two renowned basket makers—Mary Gabriel and Clara Keezer—have achieved National Heritage Fellowships. Several well-attended annual summer festivals—including one in Bar Harbor—highlight Indian traditions and heighten awareness of Native American culture. Basket making, canoe building, and traditional dancing are all parts of the scene. The splendid Abbe Museum in Bar Harbor features Native American artifacts, interactive displays, historic photographs, and special programs. Fine craft shops also sell Native American jewelry and baskets.

Mainers are an independent lot, many exhibiting the classic Yankee characteristics of dry humor, thrift, and ingenuity. Those who can trace their roots back at least a generation or two in the state and have lived here through the duration can call themselves natives; everyone else, no matter how long they’ve lived here, is “from away.”

Mainers react to outsiders depending on how those outsiders treat them. Treat a Mainer with a condescending attitude, and you’ll receive a cold shoulder at best. Treat a Mainer with respect, and you’ll be welcome, perhaps even invited in to share a mug of coffee. Mainers are wary of outsiders, and often with good reason. Many outsiders move to Maine because they fall in love with its independence and rural simplicity, and then they demand that the farmer stop spreading that stinky manure on his farmlands, or insist that the town initiate garbage pickup, or build a glass-and-timber McMansion in the middle of historic white-clapboard homes.

In most of Maine, money doesn’t impress folks. The truth is, that lobsterman in the old truck and the well-worn work clothes might be sitting on a small fortune, or living on it. Perhaps nothing has caused more troubles between natives and newcomers than the rapidly increasing value of land and the taxes that go with that. For many visitors, Maine real estate is a bargain they can’t resist.

If you want real insight into Maine character, listen to a CD or watch a video by one Maine master humorist, Tim Sample. As he often says, “Wait a minute; it’ll sneak up on you.”

In 1850, in a watershed moment for Maine landscape painting, Hudson River School artist par excellence Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900) vacationed on Mount Desert Island. Influenced by the luminist tradition of such contemporaries as Fitz Hugh Lane (1804-1865), who summered in nearby Castine, Church accurately but romantically depicted the dramatic tableaux of Maine’s coast and woodlands that even today attracts slews of admirers.

Another notable is John Marin (1870-1953), a cubist who painted Down East subjects, mostly around Deer Isle and Addison (Cape Split).

Fine-art galleries are clustered in Blue Hill, Bar Harbor, and Northeast Harbor.

Any survey of Maine art, however brief, must include the significant role of crafts in the state’s artistic tradition. As with painters, sculptors, and writers, craftspeople have gravitated to Maine—most notably since the establishment in 1950 of the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts. Started in the Belfast area, the school put down roots on Deer Isle in 1960. Each summer, internationally famed artisans—sculptors, glassmakers, weavers, jewelers, potters, papermakers, and printmakers—become the faculty for the unique school, which has weekday classes and 24-hour studio access for adult students on its handsome 40-acre campus. Many Haystack students have chosen to settle in the region. Galleries and studios pepper the Blue Hill-Deer Isle peninsula. Another craft enclave is in the Schoodic region.

Maine’s first big-name writer was probably the early 17th-century French explorer Samuel de Champlain (1570-1635), who scouted the Maine coast, established a colony in 1604 near present-day Calais, and lived to describe in detail his experiences.

Today, Maine’s best-known author lives not on the coast but just inland in Bangor—Stephen King (born 1947), wizard of the weird. Many of his dozens of horror novels and stories are set in Maine, and several have been filmed here for the big screen. King and his wife, Tabitha, also an author, are avid fans of both education and team sports and have generously distributed their largesse among schools and teams in their hometown as well as other parts of the state.

Louise Dickinson Rich (1903-1972) entertainingly described her coastal experiences in Corea in The Peninsula, after first having chronicled her rugged wilderness existence in We Took to the Woods.

Ruth Moore (1903-1989), born on Gott’s Island, near Acadia National Park, published her first book at the age of 40. Her tales, recently brought back into print, have earned her a whole new appreciative audience.

Mary Ellen Chase was a Maine native, born in Blue Hill in 1887. She became an English professor at Smith College in 1926 and wrote about 30 books, including some about the Bible as literature. She died in 1973.

For Marguerite Yourcenar (1903-1987), Maine provided solitude and inspiration for subjects ranging far beyond the state’s borders. Yourcenar was a longtime Northeast Harbor resident and the first woman elected to the prestigious Académie Française. Her house, now a shrine to her work, is open to the public by appointment in summer.

Maine’s best-known essayist was and is E. B. White (1899-1985), who bought a farm in tiny Brooklin in 1933 and continued writing for The New Yorker. One Man’s Meat, published in 1944, is one of the best collections of his wry, perceptive writings. His legions of admirers also include two generations raised on his classic children’s stories Stuart Little, Charlotte’s Web, and The Trumpet of the Swan.

Writer and critic Doris Grumbach (born 1918), who settled in Sargentville, not far from Brooklin, but far from her New York ties, wrote two particularly wise works from the perspective of a Maine transplant: Fifty Days of Solitude and Coming Into the End Zone.

Besides E. B. White’s children’s classics, Stuart Little, Charlotte’s Web, and The Trumpet of the Swan, American kids were also weaned on books written and illustrated by Maine island summer resident Robert McCloskey (1914-2003), notably Time of Wonder, One Morning in Maine, and Blueberries for Sal.

Condon’s Garage, a familiar site for fans of children’s author Robert McCloskey