An Evolutionary

Approach to Macroeconomics

| Stagflation, Unemployment, and Business Cycles: An Evolutionary Approach to Macroeconomics |

|

7 |

Throughout this book I have emphasized the contributions of my predecessors and contemporaries, the parts of the present theory that are drawn from prior work, and the cumulative character of research in any science, be it physical or social. In part, perhaps, this emphasis rests on my observation that those writers who are most assertive about the novelty of their work and the failings of their predecessors are frequently the least original; if this observation is general, there is something to be said for the opposite strategy. I would prefer to construct a tower, an arch, or even a gargoyle on a great cathedral that will last for ages than to take credit for singlehandedly constructing a shack that will be blown away by the next change in the winds of intellectual fashion. Therefore, in this chapter I will continue to admire and to build upon prior contributions, but the strategy at this point raises two difficulties. The first is that, because of the aspects of prior contributions that I shall need to discuss and the inherent difficulty of the subject, the account in this chapter cannot be quite so simple and sparing in its use of technical concepts as the previous chapters have been. Those who have never before studied any economics may have to read more slowly. I dearly hope that this admission will not stop anyone from pressing on. Naturally, I have saved the best till the last: this chapter contains some of the strongest evidence in support of the present theory and perhaps the most important application of it to current problems of public policy. Moreover, I would like to think that the noneconomist who has persevered through the book thus far is so intelligent that he or she will enjoy mastering this one climactic chapter. I realize that in saying this I flatter some readers, and perhaps indirectly and inappropriately the book as well. But I sincerely believe that it is important, for both intellectual and political reasons, to bring the laymen who have followed the argument thus far through the analysis of this last chapter. I have accordingly devoted many hours to making the argument as transparent to all intelligent readers as it is within my powers to make it. These matters are not, I like to think, explained more simply elsewhere.

The second difficulty is that the distinguished economists that I shall admire and exploit in this chapter have often disagreed, even vituperatively, with one another. This has not been a serious problem in earlier chapters. Although laymen think economists disagree about everything, there is a considerable degree of consensus about the micro-economic theory, or theory of individual firms and markets, that has helped to inspire what I have done so far. The great majority of serious, skilled economists, be they of the Right or of the Left, of this school or of that, accept basically the same microeconomic theory. They often have remarkably similar views on many practical microeconomic policies, such as the tariffs and trade restrictions discussed in the last two chapters. Unfortunately, many of the economists who use and respect the same microeconomic theory strenuously disagree about macroeconomic theory, or the study of inflation, unemployment, and the fluctuations of the economy as a whole.

This disagreement may suggest that my strategy of building upon prior work now must be abandoned. Who will agree with my praise and use of prior contributions when the authors of those contributions have spoken so disparagingly of each other’s work? Nonetheless, I have learned a good deal from each of the factions. And the centuries of work on the great cathedral must continue. The quarreling masons have not been working on this part of the cathedral from an agreed design, but I believe that they have hewed out of the granite most of the building blocks that are needed.

Why is there exceptional disagreement about macroeconomic theory and policy? Some economists suppose that one side or another is logically in error. Although there are plenty of logical errors, they can be demonstrated to be errors by rules of logic accepted by all sides. This, and the high professional rewards for such demonstrations, pretty well ensure that a school of macroeconomic or monetary thought cannot thrive for long on logical mistakes. The degree of cunning exhibited in debate by some leading protagonists of each persuasion and their skill in the use of microeconomic theory also argue that logical errors would not be the basic source of disagreement. Admittedly, there is bias and even fanaticism in some partisans that might impair their reasoning, but if so, we still need to explain why the fanatic temperament leads to more error and disagreement in one area of economics than in another.

The matter is not so clear-cut when empirical inferences are at issue. Sometimes different schools of thought emerge principally because of different judgments about inconclusive empirical evidence. When so much depends on the empirical evidence, the rewards to the empirical researcher who can show which side is most likely right are very great. If an investigation possibly could settle the dispute, it will almost certainly be undertaken. However, as I have argued elsewhere, 1 macroeconomic and monetary policies are like public goods in that they have indivisible consequences for whole nations at the least. The cause-and-effect relationships or “social production functions” for collective goods of vast domain are especially difficult to estimate, because experiments with the large units are so costly and the small number of these large units means that historical experience provides few natural experiments. Thus the empirical effects of various combinations of monetary, fiscal, and wage-price policy in different conditions sometimes cannot be determined until additional evidence becomes available. This is probably partly responsible for the special disagreement about macroeconomics.

Another source of the disagreement is that each of the competing theories, though containing valid and even precious insights, is a special theory that properly can be applied only in particular circumstances. The circumstances in which each of the competing theories is valid are different. Unfortunately, even those who respect the economics profession as much as I must admit that some of the proponents of each of these theories tend, alas, to be doctrinaire. The doctrinaire exponents of these special theories, evidently overwhelmed by the valuable insights in their preferred theory and outraged that the familiar competing theories are erroneous in the particular conditions in which the preferred theory is valid, claim that their favored theory is essentially true, whereas the competing theories are essentially false. These doctrinaire economists are guilty of unconscious synecdoche—implicitly taking the part for the whole. Of course, special or incomplete theories can be extraor dinarily valuable; indeed, no theory can be useful unless it abstracts from the unmanageable complexity of reality, so any useful theory must in some sense be incomplete.2 Even the doctrinaire exponents of each of the theories recognize that their theory is simpler than the reality it is supposed to describe, but the matters from which the cherished theory abstracts are taken to be random, unimportant, exceptional, or outside economics.

Some theories can be fatally incomplete for some purposes—such as choosing macroeconomic and monetary policies for the United States and a number of other countries at the present time. A theory that abstracts from the very essence of a problem it is intended to solve is fatally incomplete. This chapter will endeavor to show that all the familiar macroeconomic theories, although full of profound and indispensable insights, are in this sense fatally incomplete—each theory has a hole at its very center.

A final source of the special disagreement in macroeconomics, then, is the inadequacy for present purposes of each of the familiar macroeconomic theories: if any one of them had the robust and compelling character of Darwin’s theory of evolution or Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage, it might still be dismissed by some people. But it would not be dismissed, as is each of the familiar macroeconomic theories, by many of the leading scientists in the field. When scientific consensus is lacking, it is usually because the right path has not yet been found. There have been few times and places in the history of economics when an economist had a better warrant for trying an eccentric line of inquiry than in macroeconomics today.

The contending theories that will be considered here are the Keynesian, the monetarist, the “disequilibrium,” and the rational-expectations “equilibrium” models. Often, monetarist and rational-expectations or equilibrium approaches are thought to be the same, or perhaps different parts of the same theory; most advocates of the one also believe in the other. Similarly, disequilibrium theory is often considered a more modern form of Keynesian economics. For some purposes, however, it is essential to make distinctions among, and untypical combinations of, these models, which will be the case here. There are various other labels or approaches to the economy as a whole that receive attention in newspapers and political debates from time to time without generating serious attention in the technical journals. We shall not consider any of these approaches here, since they are too vague and superficial to be of any help.

Much of the debate between the Keynesians and the monetarists centers on what determines the level of spending, or the demand in money or nominal (that is, not corrected for inflation) terms, for the output of the economy as a whole. Monetarists argue that changes in the quantity of money are the only systematic and important sources of changes in the level of nominal income, whereas Keynes 1s theory also attributes a large role to budget deficits and surpluses and fiscal policy in general in determining the level of demand in the economy as a whole.

Even though Keynes’s theory, like the monetarist model, focuses mainly on what determines the level of aggregate demand, it is absolutely essential to remember that Keynes began his dazzling, world-changing book with (and built his theory in substantial part upon) the idea that one very large and quite crucial set of prices was influenced by something beyond changes in demand, and indeed beyond supply and demand.

Keynes began his argument by attacking the classical or orthodox postulate that “the utility of the wage when a given volume of labour is employed is equal to the marginal disutility of that amount of employment.” Pre-Keynesian economists had argued that if groups of workers through unions agreed not to work unless they received a stipulated wage, and that wage resulted in unemployment, this unemployment was not involuntary unemployment, but rather was due to collective choices of workers themselves. Keynes then assumed just such a situation:

A reduction in the existing level of money wages would lead, through strikes or otherwise, to a withdrawal of labour which is now employed. Does it follow from this that the existing level of real wages accurately measures the marginal disutility of labour? Not necessarily. For, although a reduction in the existing money-wage would lead to a withdrawal of labour, it does not follow that a fall in the value of the existing money-wage in terms of wage-goods would do so, if it were due to a rise in the price of the latter [i.e., a rise in the cost of living]. In other words, it may be the case that within a certain range the demand of labour is for a minimum money-wage and not for a minimum real wage…. Now ordinary experience tells us, beyond doubt, that a situation where labour stipulates (within limits) for a money-wage rather than a real wage, so far from being a mere possibility, is the normal case….

But in the case of changes in the general level of wages it will be found, I think, that the change in real wages associated with a change in money-wages, so far from being usually in the same direction, is almost always in the opposite direction. When money-wages are rising, that is to say, it will be found that real wages are falling; and when money-wages are falling, real wages are rising….

The struggle about money-wages primarily affects the distribution of the aggregate real wage between different labour-groups, and not its average amount per unit of employment…. The effect of combinations on the part of a group of workers is to protect their relative real wage.3

The central role of “sticky” (slow to change) wages in Keynes’s theory, and one of the institutions that can cause this stickiness, are also emphasized in Keynes’s chapter on “Changes in Money Wages”:

Since there is, as a rule, no means of securing a simultaneous and equal reduction of money-wages in all industries, it is in the interest of all workers to resist a reduction in their own particular case….

If, indeed, labour were always in a position to take action (and were to do so), whenever there was less than full employment, to reduce its money demands by concerted action to whatever point was required to make money so abundant relatively to the wage-unit that the rate of interest would fall to a level compatible with full employment, we should, in effect, have monetary management by the Trade Unions, aimed at full employment, instead of by the banking system.4

To be sure, Keynes’s explanation of underemployment equilibrium did not consist merely of the assumption of sticky wages; pre-Keynesian theory already ascribed unemployment to unrealistically high wage levels, and Keynes was anxious to differentiate his theory from the theory that preceded it. Indeed, Keynes argued that reductions of money wages need not bring full employment, and that if they did it involved, in essence, “monetary management by the Trade Unions.” As we know, Keynes also had new ideas about the demand for money as an asset and other matters that played significant roles in his theory. Still, the fact remains that although Keynes’s theory argued for changing aggregate effective demand, especially through budget deficits and surpluses, and claimed to explain depression and inflation solely from the demand side, it nonetheless began and in substantial part rested upon the assumption that there were forces that influenced wages and that, within limits and at least for a time, did so in ways that could not be explained in terms of increases or decreases in the demand for labor or individual decisions to trade off more or less labor for leisure.

Unfortunately, Keynes never provided any real explanation of why wages were sticky, or what determined why they stuck at one level rather than another, or for how long. This is all the more troublesome because, on first examination, this stickiness is not consistent with the optimizing or purposeful behavior that economists usually observe when they study individual behavior. This incompleteness of Keynesian theory—the reliance on an ad hoc premise that has not been reconciled with the rest of economic theory—has troubled the leading Keynesian economists (and, of course, anti-Keynesian economists) for some time.5 It also has been, in my judgment, a source of some of the failures of macroeconomic policies in the 1970s.

A similar uneasiness about an unexplained stickiness of certain wages or prices has pervaded the writings on disequilibrium theory, or the theory of macroeconomics that is based on the observation that some markets do not clear (that is, do not reach a situation where everyone who wants to make a transaction at the going price can do so, so that shortages or surpluses persist). In the seminal book in this tradition, Robert Barro and Herschel Grossman emphasized this uneasiness with exemplary scientific candor:

One other omission from our discussion is especially embarrassing and should be explicitly noted. Although the discussion stresses the implications of exchange at prices which are inconsistent with general market clearing, we provide no choice-theoretic analysis of the market-clearing process itself. In other words, we do not analyze the adjustment of wages and prices as part of the maximizing behavior of firms and households. Consequently, we do not really explain the failure of markets to clear, and our analyses of wage and price dynamics are based on ad hoc adjustment equations.6

Perhaps this admirable uneasiness about a theory built on an unexplained ad hoc premise explains why the authors, heralded as leaders of the Keynesian-disequilibrium counterrevolution, by the evidence of subsequent works have joined the flight from Keynesian economics. Monetarist models and rational-expectations equilibrium theory have the supremely important virtue of avoiding any appeal to sticky or downwardly-rigid wages that are themselves unexplained. Monetarist and equilibrium theorists assume that changes in the quantity of money tend to bring about proportional changes in nominal income because the price level readily adjusts, and that real output is determined by resource availability, technology, and other factors outside the scope of monetary and fiscal policy.

The monetarist and equilibrium theories usually are not guilty of assuming arbitrary wage or price levels, but they fail to provide any explanation of involuntary unemployment or of massive and prolonged unemployment of any sort. In more recent years, it is true, some enlightening arguments that can explain some variations in the level of employment have been introduced by monetarists and others. “Search” models, for example, have been developed, which explain some unemployment on the ground that occasionally it will be in a worker’s interest to spend full time searching for the best available job. Then there are the “accelerationist” (or “decelerationist”) monetarist arguments, which are offered as accounts of brief periods of unemployment and recession; if there is a lower rate of inflation (or a higher rate of deflation) than expected, various decisions that were made on the basis of the false expectations could, because of various lags (that are not well specified or explained), bring about temporary unemployment and reductions in real output.

The rational-expectations equilibrium theorists proceed to a conclusion that may lead newcomers to macroeconomics to think that I am describing the work of theoreticians who have lost absolutely all touch with reality. The conclusion is that involuntary unemployment and depressions due to inadequate demand simply do not occur! Although I am not in sympathy with this conclusion, I plead with readers to be patient, for the equilibrium theorists have put forth intellectually useful models of extraordinary subtlety (see, for example, the impressive work of Robert Lucas, Thomas Sargent, and Neil Wallace). Moreover, as I will demonstrate later in this chapter, it is possible to draw insights out of this quite fundamental theorizing and use them in another theory that might appeal also to those who believe that equilibrium theory as it stands is bizarre. One such insight is the equilibrium theorists’ favorite concept of rational expectations. Not all the definitions of rational expectations are exactly the same, but for present purposes it is best interpreted as the notion that people making decisions take into account all available information that is worth taking into account; economically rational expectations in this sense has all along been the usual implicit assumption in microeconomic theorizing.

Equilibrium theorists explain obvious variations in the rate of unemployment over the business cycle primarily in terms of voluntary choices concerning when appears to be the most advantageous time to take leisure or education or to forgo gainful employment in order to spend full time seeking a better job. Their arguments are too complicated to summarize without violating the general constraints that govern the exposition in this volume. The key to the equilibrium theory is nonetheless clear: it is the supposition that different groups in the economy have different information or expectations of the future, and that individual workers, despite rational expectations, temporarily misper-ceive real wages or real interest rates. Suppose that workers expect a higher rate of inflation than actually occurs. They may then conclude that a given money-wage that is offered promises a lower real wage than they eventually can obtain. Since the worker values leisure as well as money income, he may choose to remain unemployed until he is offered a job at the real wage he ultimately can command. If the worker is mistaken about the course of the price level, he may, according to this theory, remain unemployed until he discovers that his estimate of the change in the price level was wrong. Another possibility is that the misjudgment of the prospective change in the price level leads the worker to underestimate the real interest rate, so that he overinvests for a time in education and other forms of human capital. These arguments require that the employers and those workers who choose to remain employed have different information or judgments about the future course of the price level than do the unemployed workers. If the arguments are to explain the high and prolonged levels of unemployment that sometimes occur, they also require enormous changes in the supply of labor from relatively modest changes in perceived real wages.

Tne models of the kind I have just described fail to persuade even many monetarist economists, and of course they do not convince Keynesians. Robert Solow, for example, finds “these propositions very hard to believe, and I am not sure why anyone should believe them in the absence of any evidence.”7 But they have attracted a huge amount of attention among macroeconomists; my hunch is that there is an intuitive perception that the models eventually could help economists to work out something better.

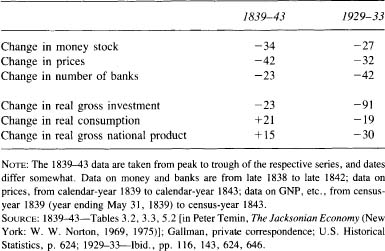

Although the search, accelerationist/decelerationist, and equilibrium theories, which in most formulations attribute any mac-roeconomic problems to mistaken expectations, can explain some variations in the level of employment and the rate of utilization of other resources, they are not nearly sufficient to explain the depth and duration of the unemployment in the interwar period. If the economy is always at a full employment level of output, except when and only for as long as the rate of inflation that was anticipated exceeds that which occurs, why did the depression that began in the United States in 1929 and ended only with World War II involve such an enormous and prolonged reduction in employment and real output? Consider also the case of Great Britain in the interwar period. Britain then as now used a system for measuring unemployment that by comparison with current U.S. practice understates the degree of unemployment; yet, from shortly after World War I until World War II, Great Britain almost never recorded less than 10 percent unemployment.

This interwar experience could be explained on an expectations hypothesis only if people, in the midst of the greatest depression ever, expected an inflation so dramatic that it made sense to refuse to accept any wage or price unless it was significantly above the current levels, or far above the level that would clear current markets. This is—to put it mildly—doubtful, and it is even more doubtful that most people would have persisted in such wildly erroneous expectations for a dozen years in the case of the United States or for twenty years in that of Great Britain. Neither is it credible that, when unemployment and welfare arrangements were so much less generous than today and when most workers were the only source of support for their families, the natural rate of unemployment could leave a tenth to a fourth of the work force unemployed.

The inability of the search, monetarist, and equilibrium theories to explain the magnitude and tenacity of unemployment in the interwar period suggests that they are seriously incomplete. Some of the leading advocates of the expectations-oriented theories concede this and also agree that they are not nearly sufficient to explain the great depression.

Perhaps there are analogies to monetarist and equilibrium theories in the histories of other sciences. The avoidance of ad hoc assumptions is commendable and the effort to explain unemployment and business cycles with complete fidelity to well-tested theory is similar to what I advocated in chapter 1 and have tried to do in this book. But the unwillingness in most monetarist and equilibrium theorizing to go beyond the conventionally defined borders of economics or to take a completely different perspective on the problem needs rethinking. So does the attachment to “equilibrium,” even in the wake of the colossal unemployment and reduction in real output in the interwar period. Equilibrium is a useful concept only if there is disequilibrium too. If the disequilibrium approach is ruled out and the economy is deemed to be in or near equilibrium even in major depressions and recessions, what observation or set of observations possibly could tend to call the theory into question? Equilibrium theory may have something in common with the attachment of nineteenth-century physicists to the concept of an “ether” that was supposed to fill all space and suffuse itself even into material and living bodies. The work of Einstein and others has led to the total abandonment of the unnecessary concept of ether. With a similarly excessive attachment to established theory, the Ptolomaic astronomers constructed “epicycles” to reconcile their observations of the planets’ orbits with their assumption that the earth was the center of the system. Even given these epicycles, additional observations often required new estimates of cycles or epicycles of particular planets, with the result that new anomalies would crop up in other parts of the system. The Copernican heliocentric astronomy as developed by Kepler and Newton offers a far simpler and more persuasive conception.8 Probably the intertemporal elasticities of supply of labor required to explain the unemployment in Britain and the United States in the interwar period as the result of voluntary choices of workers who thought they were well advised to hold out for higher expected real wages would introduce new anomalies into our econometric studies of labor supply. These studies have not revealed any great sensitivity of the amount of labor offered to small changes in the real wage.

The shortcomings of monetarism and equilibrium theory probably persuaded some economists to remain a while longer with Keynesian theory, notwithstanding its utter dependence on the unexplained assumption of sticky wages. But the Keynesian model (like some of the other macroeconomic models) has lately been contradicted by stagflation, or simultaneous inflation and unemployment. A Keynesian model cannot explain how high inflation and high rates of unemployment can occur together, as they did in the 1970s, and this is a problem for some of the other macroeconomic models also. Some Keynesian economists have tried to explain recent macroeconomic experience in Britain, the United States, and some other countries in terms of negatively sloped Phillips curves (observed tendencies for wage and price increases to vary inversely with the level of unemployment). There is no need to invoke the monetarist criticisms of the Phillips-curve concept to show that it is inadequate, for it is only a statistical finding (or a statistical finding for a certain period) in search of a theory. An explanation of stagflation is not an explanation at all unless it includes a general explanation of why a Phillips curve should have this or that slope, and why the curve shifts if it is alleged to shift. Any Phillips-curve relationship must be derived from the interests and constraints faced by individual decision-makers. The lack of an adequate explanation in Keynes of stagflation or Phillips curves—especially the tendency for short-run Phillips curves to move upward and become steeper over long periods of inflation—must have a lot to do with the apparent growth in skepticism about Keynesian economics in recent years. (Although he certainly exaggerated, Lord Bal-ogh did not miss the direction of change when he lamented that “anti-Keynesianism was the world’s fastest-growth industry.”)9

“Implicit contracts” have also been brought to bear in efforts to explain the recent stagflation in ways that can be reconciled with Keynes. Implicit contracts have been used to explain such phenomena as very long-term employment relationships and temporal variability in levels of effort asked of employees, combined with stable wage levels, and for purposes such as these they are a most illuminating concept. They are not sufficient to explain any significant amount of unemployment, much less simultaneous inflation and unemployment. Indeed, insofar as implicit contracts bear on stagflation and unemployment, they are more likely to reduce than increase the extent of it. Essentially, workers and employers will enter into implicit contracts, like explicit ones, only if they feel that will be advantageous. People are risk averse, as implicit contract theory rightly assumes,10 so that, other things being equal, they will prefer to enter into contracts that reduce the probability of layoffs. They could even gain from slightly lower wages if this were combined with an implicit or explicit agreement that the employer would make every possible effort to keep them employed. The employers would not gain from contracts with individual workers stipulating rigid wages or other conditions that would increase the probability of layoffs; rigid wages constrain employers and deny them potential gains. The most profitable implicit contract between employers and employees would enable them to let the wage, in effect, fluctuate in such a way that employers and employees jointly maximized the difference between the value of leisure and alternative work to the employee and the marginal revenue product of labor for the employer. These functions shift, sometimes frequently, so only a flexible wage would be consistent with the employment of the mutually optimal amount of labor. Of course, wages most often are not very flexible, but the main reason for this, as we shall see later, is not implicit contracts.

It can be difficult to work out a long-term contract that is completely successful in maximizing the joint gain of the worker and the employer, since only the worker may know the value to him of his leisure time and only the employer may know how much a given amount of labor will add to his revenue. In practice the employers and employee may not succeed in finding exactly that wage and quantity of employment that will give them the maximum joint gain over an extended period. One of the possibilities is that they will make an arrangement that ends up with the worker working less than he would have worked had there been perfect information on all sides. But it is preposterous to attribute any substantial amount of unemployment to this possibility, since if the losses of this nature are large, the two parties would not have any incentive to make a long-term contract in any case and would rely instead on a series of “spot market” deals. Thus implicit contracts cannot explain any substantial amount of unemployment, and on balance almost certainly reduce unemployment. The common arrangement whereby firms strive to keep workers on the payroll even during slack times and workers in turn do extra work at rush periods without demanding an increased wage is probably the most common type of implicit contract, and it reduces unemployment.

There are also “cost-push” explanations of inflation and stagflation, which attribute the inflation or stagflation to price and wage increases by firms and unions with monopoly power. As others have shown before, the typical cost-push arguments are manifestly unsatisfactory. They offer no explanation of why there should be continuing inflation or why there should be more inflation in one period than in another. They do not explain why an organization with monopoly power would not choose whatever price or wage it found most advantageous as soon as it obtained the monopoly power, after which point it would have no more reason to increase prices or wages than a pure competitor. In the absence of some adequate explanation of why organizations with monopoly power do not take advantage of that power when they first acquire it, or some explanation of why monopoly power should increase over time in a way consistent with the history of inflation or stagflation, the cost-push arguments are unsatisfactory. They must also be accompanied by some account of why governments or central banks would provide increased demand after the alleged cost-push had increased wages and prices, so that the cost-push would culminate in inflation rather than in unemployed resources. (With the theory offered in this book and some other ideas, one could construct a valid theory of inflation that would have a faint resemblance to the familiar cost-push arguments, but these arguments have been the source of so much confusion that there is probably more loss than gain from doing so.)

What must we demand of a macroeconomic theory before we can find it even provisionally adequate? First, the theory should be deduced entirely from reasonable and testable assumptions about the behavior of individuals: it must at no point violate any valid microeconomic theory. This means, in turn, that it must not contain ad hoc, unexplained assumptions about anything, including sticky or downwardly rigid wages or prices; such rigidities may be introduced only if they are in turn explained in terms of rational individual behavior or rational behavior of firms, organizations, governments, or other institutions (and the presence of such institutions must again be explained in terms of rational individual behavior). I think the vast majority of economists, whatever existing macroeconomic theory they might prefer, agree that a macroeconomic theory should make sense at a microeconomic level as well. This is evident from the support for the work on the microeconomic foundations of macroeconomic theory going on in all camps (consider, for example, the wide influence of Edmund Phelps’s volumes on the microeconomic foundations of macroeconomics).11

Second, an adequate macroeconomic theory must explain involuntary as well as voluntary unemployment and major depressions as well as minor recessions. There are, of course, large numbers of people who voluntarily choose not to work for pay (such as the voluntarily retired, the idle rich, those who prefer handouts to working at jobs, those who stay at home full time to care for children, and so on) and, given the way unemployment statistics are gathered in the United States and other countries, no doubt some of these show up in the unemployment statistics. Yet common sense and the observations and experiences of literally hundreds of millions of people testify that there is also involuntary unemployment and that it is by no means an isolated or rare phenomenon. Depressions in the level of real output as deep as those observed in the Great Depression in the interwar period surely cannot be adequately explained without involuntary unemployment of labor and of other resources. The Great Depression was an event so conspicuous that the whole world observed it, and the political and intellectual life in most countries was revolutionized by it. Only a madman—or an economist with both ‘ ‘trained incapacity” and doctrinal passion—could deny the reality of involuntary unemployment. The first condition set out above entails that the involuntary unemployment is not adequately explained unless it can be shown to be possible even when every individual and firm or other organization involved is rationally acting in its own interest; the motive generating the involuntary unemployment, that is, the interests that are directly or indirectly served by it, must be elucidated.

Third, the theory must explain why the unemployment is more common among groups of lower skill and productivity, such as teenagers, disadvantaged racial minorities, and so on. This outcome may seem only natural to the laity, but many of the prevailing theories about variations in employment and unemployment do not predict the pattern that is observed. The search-theory approach (like the notion of “fric-tional unemployment”) predicts the most unemployment in “thin” markets where buyers and sellers are less numerous; an individual must search longer to find a counterpart for his employment contract. Generally, professional and other highly skilled workers are the most specialized and operate in the thinnest markets, and they should by the search theory have the highest unemployment rates. The largest single labor market is that for unskilled labor, where search unemployment should be lowest.

Fourth, the theory must be able to accommodate both equilibrium and disequilibrium, among other reasons because neither concept is empirically operational without the other.

Fifth, an adequate macroeconomic theory must be consistent with booms as well as with busts—with periods of unusual prosperity and with periods of underutilized productive capacity. It must be consistent with what we loosely call the “business cycle/’ although the absence of strong regularities in the length and extent of periods of prosperity and recession suggests that “business fluctuations” would perhaps be a better term. In other words, as Kenneth Arrow points out,12 the theory must be consistent with the observation that neither depressions nor full-employment levels of production appear to sustain themselves indefinitely.

Sixth, the theory should be able to explain, without ad hockery, the really dramatic differences across societies and historical periods in the nature of the macroeconomic problem. If economic history were more widely taught in economics departments, the need for this requirement would long ago have been obvious, but modern trends in economics and econometrics have meant that economic history has, alas, been crowded out and even belittled.

Seventh, since the greater the explanatory power of a theory, other things being equal, the greater the likelihood that it is true, the theory ideally should be able, at least in its full or complete form, to explain some other, extra-macroeconomic phenomena. This is not an absolute requirement, but we should be uneasy if it is not met and reassured if it is. I must repeat again that the theory need not be monocausal, so that any number of factors that are exogenous to it may be terribly important, for macroeconomic problems as well as for other matters.

Eighth, as we already know from chapter 1, the theory should be relatively simple and parsimonious.

I submit that the following theory, when combined with familiar and straightforward elements from the four macroeconomic theories set out earlier in this chapter and with what has been presented in earlier chapters of this book, meets all eight of the above conditions. Partly to underline the simplicity of the argument, especially in contrast to many of the recent contributions to macroeconomics, and partly to reach students and policy-makers, the discussion will use only the most basic and simple theoretical tools.

I shall first explain, subject to the constraints entailed in the first of the above conditions, one source of the involuntary unemployment of labor. Even though it is natural to begin with the simplest and most straightforward source and type of unemployment, it is vitally important not to use this first explanation in isolation from the rest of the argument. There is also unemployment or underutilization of machinery and other forms of capital in a depression or a recession, and although this usually does not conjure up such painful visions as does involuntary unemployment of labor, it also involves waste of productive capacity and in addition often contributes to the losses workers suffer in such times, since the idle capital means that less capital is combined with labor, and the demand for labor and wages can then tend to be lower than they might otherwise be. The demand for labor obviously depends on what is happening in the product markets in which the firms that employ labor sell their output, so the amount of involuntary unemployment of labor most definitely cannot be determined without looking at conditions in product as well as labor markets.

It would be easy but unhelpful to explain involuntary unemployment in terms of some allegedly persistent tendency of those involved to choose outcomes that are inconsistent with their interests. So I shall assume rational expectations, in the sense that individuals take into account all the information that it pays them to take into account—all available information that they expect will be worth more to them than it costs.

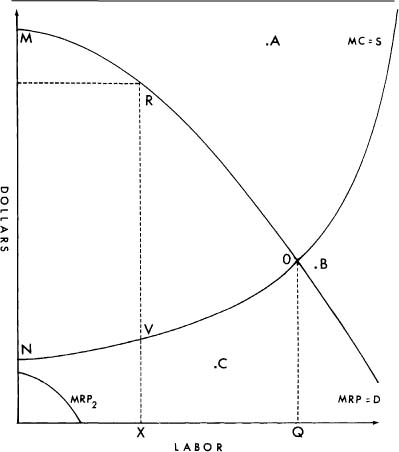

We also must define involuntary unemployment very strictly. If we let a wide variety of situations count as involuntary unemployment, it would again be easy to explain its existence, but nothing much would be gained. In particular, we must be certain that we do not include in our definition any voluntary unemployment, which is easily explicable as a preference for leisure or home-produced output over the earnings from work. I do this by reference to figure 1. This depicts, in the MC (marginal cost) or supply curve, the value of the time of workers in the form of leisure, home-produced goods, and any other opportunities. The demand for labor, or MRP (marginal revenue product) curve, consists of points on the separate marginal revenue product of labor curves of firms in diverse industries that have a demand for whatever type of labor is at issue.13 In the interest of saving a few moments of time for those intellectually versatile noneconomists who have persevered through this chapter, I point out that MC or the marginal cost curve for labor is assumed to rise because as more labor is taken, workers with a lesser attraction to the labor force must be persuaded to take paid employment, and because each worker must be paid more to forgo leisure the more hours of work he has already supplied. The D curve declines because, among other reasons, the law of diminishing returns entails that additional labor of a given type will eventually add smaller increments to output.

At points to the right of the intersection of the two curves, such as point B, there can be no involuntary unemployment; the value of leisure or alternative opportunities is above point B, so no one will accept a job at that wage level, and when the amount of labor given by point B is already employed the employers would find that wage level B would cost more than the additional labor was worth to them anyway. In terms of the first quote from Keynes earlier in this chapter, we would have to move leftward to the intersection of the two curves to find the point where “the utility of the wage … is equal to the disutility of that amount of employment.” Similarly, if anyone demanded a wage level such as that at point A there would also not be involuntary unemployment, because A is higher than the marginal revenue product of labor; the worker would be asking for a gift more than a job, for any employer will lose money from employing him at that wage. At a point such as C there is similarly no involuntary unemployment; this is below the value of time in alternative uses and the worker does not accept any job that pays only a wage of C

We could also postulate a different type of labor with so little value to employers that the MRP curve was for all or almost all of its length below the MC curve, as MRP2 is. In this depressing case, the worth of that type of labor is so low that no employer would gain from taking it, even if the wage were so low that even a normally industrious worker would not take it. A case such as this may be more tragic than involuntary unemployment, but we must not confuse it with involuntary unemployment. We know that patients in a hospital are not working, but we do not count them as or usually describe them as unemployed; the problem of people who cannot be productive, or whose productivity is so low that no one could gain from hiring them even if they put a negligible value on their time, is a problem of unproductive resources, not a problem of unemployment of resources—it does not imply any unutilized productive capacity.

There can be involuntary unemployment only in the roughly triangular area MNO. There is involuntary unemployment in our strict sense only if a worker’s employment would add an amount to an employer’s revenue that is greater than the value that the worker puts on his time, taking the value of leisure and all other opportunities for the worker into account.

Similarly, if a worker is unemployed because he believes that it is in his best interest to spend more time searching for work and therefore declines inferior employment opportunities while searching, this again is not involuntary unemployment. Personal observation may tell the reader that it is easier to get a job if one already has one, and that this type of search unemployment is rather rare. Whether this is true or not, if this type of unemployment occurs we must not call it involuntary; the worker is simply investing his time in the way that he believes will maximize lifetime income arid satisfaction. If this type of unemployment were somehow prohibited, the national output and welfare would decline in the long run, since the worker in question presumably knows his interests and situation better than anyone else. On the other hand, if there is a social institution or public policy that inefficiently increases search costs or time spent in job queues, the extra searching is then required by the institution or policy, and this extra searching is no longer an investment that generates a social gain: any extra search unemployment due to such arrangements is defined to be involuntary.

Suppose, arbitrarily, that only OX workers are employed; there is then strictly involuntary unemployment of XQ workers, as that many have a marginal revenue product in excess of the marginal cost of their time. Note now the triangular area RVO, giving the area that is both above the marginal cost of the relevant labor and below the marginal revenue product of labor curve. This area represents a social loss, for the time of the workers would be worth more to employers than it is worth to themselves. Above all, note that mutually advantageous bargains can be worked out between the unemployed workers and the employers; they both will be better off by agreeing to an employment contract at a wage level between the two curves. This will always be true if there is involuntary unemployment in the strict sense.

In a Keynesian “unemployment equilibrium” these same gains would accrue to both employers and employees from making an employment contract; as time goes on, more such contracts will be made, so the “unemployment equilibrium” is not an equilibrium at all. Keynes was also talking about genuinely involuntary unemployment. The difficulty now being described is in fact a staff stuck right through the heart of Keynes’s explanation of unemployment. I hasten to add that several others, such as Don Patinkin, have found this difficulty in Keynes earlier, usually by somewhat different paths, and that this is one of the reasons so many good economists have been searching for a solid microeconomic foundation for Keynesian economics, or else for an alternative to it. The fact remains that we do not have a satisfactory explanation of involuntary unemployment in Keynes, or for that matter in disequilibrium theory.

The involuntarily unemployed workers and employers in the real world do not have perfect knowledge, of course, and they may not know for a time of the gains they would acquire if they made a deal. Thus some of the workers might not become employed for a time. They would have to search, as Vould the employers, to obtain the mutual gains. Still, there need be no involuntary unemployment, because the workers would either continue at other jobs while they looked for better work, or else they would decide that the best way they could use their time was to invest it in searching; and as we indicated that sort of investment is not involuntary unemployment any more than investment in education is. One could appeal, as some equilibrium theorists do, to asymmetries in information that would make employers and employees estimate the MRP or MC curves differently, but this is an arbitrary and empirically implausible solution. Such misperceptions presumably could not last for twenty-year periods, such as the unemployment in Britain between the wars, or could not confuse such a large proportion of the work force as was unemployed in the United States from 1929 until World War II. We must seek some stronger and more durable influence preventing the mutually advantageous transactions between the involuntarily unemployed and present or prospective employers.

For the economist, it is natural to ask who in the government or elsewhere might have an interest in blocking the mutually advantageous transactions with the involuntarily unemployed. The president and governing political parties would not have any direct interest in blocking such transactions; they would risk losing the votes of both the prospective employee and the prospective employer. Everyday observation tells us that incumbents wish to run for re-election on “peace and prosperity” or “you never had it so good” platforms. The population at large would not want to block the transaction out of general human sympathy, and the business community as a whole would want the extra employment because of the extra demand it would bring to business in general.

The main group that can have an interest in preventing the mutually profitable transactions between the involuntarily unemployed and employers is the workers with the same or competitive skills. They have a substantial interest in preventing such transactions, for their own wages must be lowered as extra labor pushes the marginal revenue product of labor down. The only way that the existing workers can prevent the mutually advantageous transactions is if they are organized as a cartel or lobby or (as is very often the case) are in one way or another informally able to exert collusive pressure. The only other group that could have such an interest would be a monopsonistic (or buyers') cartel or lobby of employers; it would need to block mutually advantageous transactions between individual employers and workers to keep wages below competitive levels. No model of involuntary unemployment or theory of macroeconomics that ignores the motive that makes unemployment occur can be satisfactory.

The foregoing account has for expository reasons focused only on the labor market and temporarily assumed no cartelization or governmental intervention in the rest of the economy, where prices afe perfectly flexible. This ensures that employers always will be able to sell their outputs. Of course, the same argument applies to the market for other factors of production and to product markets, where these applications are often much more important. The downward sloping curve in the figure could just as well have been a demand curve for a product and the upward sloping curve the supply curve or marginal cost of producing it. If something, such as a price that was too high, created underutilization of productive capacity, there would be the possibility of mutually advantageous gains in the triangle. Again, the only party that could have an interest in blocking these mutually advantageous transactions between buyers and actual or potential sellers would be the firms that profited from a noncompetitive price. They could prevent the mutually advantageous transactions only if they were organized as a lobby or cartel or could collude informally or tacitly.

As disequilibrium theorists such as Edmond Malinvaud have shown,14 the price that does not clear the market (that is, consummate all mutually advantageous transactions) in a product market can also contribute to unemployment of labor or excess capacity in other product markets. Later in this chapter I shall consider the combined effects of distributional coalitions in both factor and product markets at the same time. Because of the findings of the disequilibrium theorists and of what I will present later, the above analyses of the labor market cannot be used in isolation and must be applied together with similar analyses of other factor markets and product markets.

The more extensive the special-interest groups and the non-market-clearing prices lobbying and cartelization bring about, the greater the variations in the rates of return for similar workers and for capital. The greater these variations, the more it pays to search for the higher returns. This extra search, however, is not a socially efficient expenditure on the gathering of information, and it is required only because of the special-interest groups, so it also generates involuntary unemployment. Some time is spent in job queues because of the non-market-clearing prices and wages, which further increases involuntary unemployment.

We shall soon see that the above approach has some surprising and testable implications when placed in a general equilibrium context, but it will first be necessary to refer back to Implication 6 in chapter 3. That implication was that distributional coalitions generate slow decision-making, crowded agendas, and cluttered bargaining tables. In many cases, we found, it was also advantageous for these coalitions to be quantity-adjusters rather than price-adjusters.

The implication explains why many prices and wages in some societies are sticky. It takes a special-interest organization or collusion some time to go through the unanimous-consent bargaining or constitutional procedures by which it must make its decisions. Since all the most important decisions of the organization or collusion must be made in this way, it has a crowded agenda. Since the distributional coalition often has to lobby or bargain with others, it may face other organizations or institutions with crowded agendas, so bargaining tables may be cluttered, too. Thus it can be a slow process for a price or wage that is influenced or set by lobbies or cartels to be determined. Once the price or wage is determined, it is not likely to change quickly even if conditions change in such a way that a different price or wage would be optimal for the coalition. So special-interest groups bring about sticky wages and prices.

It is widely observed that prices and wages are less flexible downward than upward. Malinvaud, for example, speaks of the “commonly believed property according to which prices are more sticky downward than upward,”15 and my colleague Charles Schultze’s influential early work on stagflation builds partly upon that premise.16 This observation is puzzling; any decision-makers, however much monopoly power they have, should choose the price or wage that is optimal for them and should on average lose just as much from a price that is too high as from one that is too low. It might seem, then, that if prices are sticky for any reason they should be equally sluggish going in each direction. There is observed stickiness going each way but many observations that this stickiness is more extreme or systematic on the down side. A cartel or lobby with slow decision-making will take time deciding either to raise or to lower prices and presumably its collective decision-making procedures are equally slow in each direction.

We can see from the analysis that led to Implication 6 that there is nonetheless an asymmetry. If one member of a cartel charges a lower price than the agreed-upon price, that hurts the others—they get fewer sales and lower prices. If a cartel member charges a higher price than the agreed-upon price, on the other hand, there is no harm to the others in the cartel. If there is a reduction in demand a cartel may wish that it had chosen a lower price, but because of the conditions adduced in the discussion of Implication 6 the decision to lower the cartel price will come only after some delay. If, from a position of equilibrium, there is a sufficiently small increase in demand facing the firms in the cartel, each firm can sell a little more at the old cartel price and enjoy increased profits, although not as much of an increase as if the cartel price had been adjusted promptly. Now consider an unexpected increase in demand so large that each firm can get more than the cartel price. No firm could have an objection if any other firm charged more than the cartel price, so for a time there will be upward flexibility in prices. The argument requires that monopolistic cartels are more common than buyers’ cartels, and this appears to be the case.17 A testable implication of the theory is that the converse phenomenon would be evident in monopsonistic cartels.

The location of price and wage stickiness across industries is also consistent with the theory. The theory implies that in sectors where there is special-interest organization there will be more stickiness, and (because of Implication 3) in industries where there is a fairly small number of firms that can collude more easily, there will on average be less price flexibility than in industries with so many firms that they cannot collude without selective incentives. Those large groups that are organized because of selective incentives may have even slower decision-making.

The sluggish movement of wages that are set by collective bargaining is well known. Wage flexibility appears to be particularly great in temporary markets where organization is pretty much ruled out, as in the markets for seasonal workers, consultants, and so on. There also appears to be less flexibility in manufacturing prices than in farm prices (except when farm prices are determined by governments under the influence of lobbies). This has been noted by observant monetarists as well as by Keynesians. Phillip Cagan, a leading monetarist, summarizes the evidence clearly and fairly:

While manufacturing prices have at times fallen precipitously, as in the business contractions of 1920-21 and 1929-33, usually they do not. To be sure, the available data do not record the secret discounting and shading of prices in slack markets, and actual transaction prices undoubtedly undergo larger fluctuations than the reported quotations suggest. The difference between reported and actual prices [will be] discussed further. It is not important enough, however, to invalidate the observed insensitivity of most prices to shifts in demand.18

F. M. Scherer and many others also present data indicating that there are greater fluctuations in farm and commodity prices than in prices in concentrated manufacturing industries.19

The present theory also predicts that there will be more unemployment among groups in the work force that have relatively low skills and productivity, as our list of conditions for a suitable macroeconomic theory suggested it should. As Implication 6 explained, distributional coalitions will more often than not bargain for a wage or price and permit employers or customers to make some of the decisions about who gets the resulting gains, so that the coalition will be able to minimize divisive conflict over the sharing of the gains of its collective action. When wages and salaries are set above market-clearing levels, the employer will choose and attract more qualified employees than with competitive wages, and the less productive may find that at the wage levels that have been established it is not in an employer’s interest to hire them. If the less-qualified and the employers were free to negotiate any employment contracts they wished, the wages would vary with productivity, and workers with positive but relatively low productivity would find it easier to obtain jobs. The worker who is trained for a high-skill occupation but does not get a job because he or she has below-average skills for that occupation will oftentimes be able to get a job in a lower-paying occupation with lower average qualifications; but the unskilled worker is less likely to have any such inferior alternative employment to turn to. Of course, other factors are also important. For example, some of the construction and manufacturing activities that have strong unions and high wages are also sensitive to the business cycle and accordingly have unstable employment patterns.

Implication 6 also tells us something about how those prices and wages influenced by special-interest groups will react to unexpected inflation or deflation. A cartel or lobby will seek whatever price it believes best, but for the reasons explained in chapter 3 it will seek agreements or arrangements that last for some length of time. Collective bargaining agreements in the United States offer a clear, though perhaps extreme, example of this; they customarily last for three years.

Now suppose that there is unexpected inflation or deflation. With unexpected inflation the price the special-interest group obtained will become lower in relation to other prices than the group wanted or expected it to be, but the group will not quickly be able to change the relevant agreement or legislation. Since the cartel or lobby could only have gained from setting a supracompetitive or monopoly price, unexpected inflation will make the relative price it receives less monopolistic than intended. The price will also be closer to market-clearing levels than expected. An unexpected inflation therefore reduces the losses from monopoly due to cartelization and lobbying and the degree of involuntary unemployment. In a period of unexpected inflation an economy with a high level of special-interest organization and collusion will be more productive than it normally is.

In a period of unexpected deflation, by contrast, the price or wage set by a distributional coalition will for a time be even higher than the coalition expected or (if it had gotten its way completely) even higher than it desired. This will mean that the losses from monopoly are greater than normal and that the relative prices are even farther above market-clearing levels than normal, so involuntary unemployment will be unusually high.

We now have a better explanation than has previously been available for the familiar observation that in most economies unexpected inflation means reduced unemployment and a boom in real output, whereas unexpected deflation (or disinflation) means more unemployment and a reduction in real output. Although it has been shown in formal general-equilibrium models (in which special-interest groups were not taken into account) that “money is neutral,” that inflation has no effect on relative prices and no impact on real output, we now see why this conclusion does not hold for most economies in the real world.

Naturally, if inflation rises to triple-digit levels (as it has in several countries) and there is great uncertainty about the future rate of inflation, special-interest groups will then seek to lobby or to bargain for prices or wages that are indexed to the rate of inflation. I have not examined the process when inflation rates are that high, but I would hypothesize that the economic results in real terms of higher-than-ex-pected inflation or unexpected disinflation in such circumstances would be sensitive to the imperfections of the available price indexes. And these imperfections are substantial even in the best of circumstances. Strictly speaking, each consumer needs a separate price index if he or she is going to be perfectly indexed against inflation, because each consumer tends to buy a different bundle of goods and the price of each good tends to change by a different amount. But this proof that no special-interest organization could find an ideal price index for all its members is of minor importance when compared to the great shortcomings of the existing price indexes, even in the countries with the best statistics. The very substantial mismeasurement of the rate of inflation in the United States by the Consumer Price Index is well known. Some of the defects of this index could be corrected readily were there no lobbies resisting such correction, but other difficulties cannot in practice be solved. There is no way adequately to measure the changes in the quality of products, for example, and no way to adjust appropriately for the fact that consumers will take relatively less of whatever products rise most in price, so these goods will be overweighted in the price index. These and other problems are so difficult in practice that in the United States in the 1950s and early 1960s, when measured rates of inflation were already significant, skilled economists were seriously debating whether there was in fact any inflation at all.20 Thus the impact of unexpected inflation or unexpected deflation is usually mitigated by indexing only in those cases where inflation has proceeded for some time at high levels.

It is now time to extend the argument by recognizing that there are many different industries or sectors in the economy and that what happens in each sector affects and is affected by what happens in other sectors: that is, the argument must be put in a general equilibrium context.

To understand the present theory fully in a general equilibrium context, we must draw upon an important but inadequately appreciated insight of Robert Clower’s.21 The essence of Clower’s insight can be seen by returning to figure 1. As we remember, there were unexploited gains unless mutually advantageous trades had entirely eliminated the triangular area. All the gains can be captured only if the price for at least the last unit of labor sold is the one given by the intersection of MRP and MC (demand and supply curves). If that price is not achieved^ or if for any reason not all of the mutually beneficial trades are completed, the incomes of both the unemployed workers and the employers will be smaller. When we shifted to cartels in product markets it was obvious that the same point held: all the mutually advantageous transactions will not be consummated unless the price is right, at least for the last unit, and if all the gains from trade are not achieved, incomes on both demand and supply sides will be lower. If we now think of a complete general equilibrium system, as Clower did, we see that if there is not exactly the right price in every market, there will be unexpioited gains from trade. If the general equilibrium system does not come up with an ideal vector of prices, then, there will be lower incomes throughout the economy. These losses—that is, the absence of the gains from many mutually advantageous but unconsummated transactions throughout the economy—will mean that aggregate demand for the economy’s output is less than it would have been had the perfect vector of prices existed, and it could be very much less. Thus Clower discerned a factor that in principle could make the output of the economy as a whole fluctuate.

For some time, Clower’s fundamental insight did not receive much attention. Later it was exploited by the disequilibrium theorists, but with the demoralization of some of these theorists by the lack of any explanation of why markets did not clear and the exodus from Keynesian types of thinking, its use seems to have diminished. I have been told by a deservedly eminent macroeconomist that if a general equilibrium system does generate a mistaken vector of prices, people can immediately gain from making the trades that will correct that vector of prices, and the system therefore quickly converges on the full employment level of output, so Clower’s point is insignificant. I suppose that Clower’s insight has not received more attention because most economists believed that there was nothing to stop the mutually advantageous trades; they would take place, if not promptly, then after only a modest lag, so Clower’s point was of only transitory significance.

If my argument is right, there are those who do have an interest in blocking the mutually advantageous trades, and in some societies they are organized to block theiji, sometimes indefinitely. In stable societies these interests become better organized over time, so the problem, far from being a mere lag, can increase with time. The inefficiencies that result from special-interest groups, which my analysis in previous chapters indicates can be very large indeed, in turn affect the level of demand. Of course, if the accumulation is gradual, as I claim it is, no large macroeconomic fluctuations need emerge from this accumulation alone.

Now suppose that there is unexpected deflation or disinflation, or a sudden rise in the price of oil, or any other major change that entails that the economy can reach its full potential, or even return to its normal level of real output, only if it has new prices throughout the economy. As we know from the preceding account of unexpected deflation and disinflation, in an economy with a dense network of distributional coalitions the terms of trade will shift in favor of the organized sector. The slow decision-making explained by Implication 6 will keep the sector with organized special-interest groups from adjusting for a time, whereas what Sir John Hicks has aptly called the “flexprice” sector will adjust immediately. Accordingly, the degree of monopoly in the society and the number who are searching, queueing, or unemployed in non-market-clearing sectors increases. With an increase in the degree of monopoly and an increase in the amount of time spent in searching, queueing, and unemployment, there is less income in the society, and demand in real terms falls off. In other words, because of slow decision-making, crowded agendas, and cluttered bargaining tables, it can take a considerable time in some societies for a vector of prices as good as the pre-deflation or pre-shock vector to emerge. The result is a reduction in the demand for goods and for labor and other productive factors throughout the economy: there is a recession or depression.

Those prices set by distributional coalitions at monopolistic and above-market-clearing levels before the unexpected deflation or unexpected shock will now tend to be even higher than before, not only because of the direct effects of the deflation or the shock, but also because of the reduction of demand in real terms due to the general equilibrium effects that Clower and the disequilibrium theorists have pointed out. This in turn makes long-term investment risky, so investment spending can also fall off fast. Each of these developments will exacerbate the others, so there can be a vicious downward spiral, although the tendency of special-interest organizations and collusions to readjust their prices to the new situation will eventually offset the forces that reduce real output.

Though Malinvaud and the other disequilibrium theorists simply assumed some non-market-clearing prices and wages, their analyses of the process now being described is quite similar. Malinvaud most usefully has pointed out that in such circumstances there is “Keynesian” involuntary unemployment as well as “classical” involuntary unemployment.22 The former, very loosely speaking, is the additional unemployment brought about because the quantity of goods purchased in the product market has fallen off due to non-market-clearing prices in those markets, which in turn reduces firms’ demands for labor and multiplies the loss in employment due to wages that are above market-clearing levels. When wages are above market-clearing levels but the prices of goods are not, the involuntary unemployment that results is defined as “classical.” Malinvaud judges that Keynesian unemployment is more common than classical unemployment.

According to my argument, we would need to look at the pattern of special-interest organization by sector to determine this, and the answer would vary from place to place and time to time. But whether Malinvaud is right or not, it is absolutely certain that the extent of involuntary employment cannot be understood, even to a first approximation, by looking at the coalitions in the labor market alone. I began with involuntary unemployment due to cartelization in the labor market because that is the simplest case to understand, but it need not be the most important source of involuntary unemployment; all types of cartels and lobbies need to be taken into account together for a satisfactory analysis of the involuntary unemployment of labor or the underutilization of any other resource.

As the earlier account of unexpected inflation should make clear, the opposite process tends to occur when unexpected inflation or major favorable exogenous events (such as major technological innovations or resource discoveries) happen. An economy can enjoy a boom in which the loss from its distributional coalitions is less than normal, and this can bring about a similar spiral of favorable effects until the special-interest groups have adjusted to the new situation, the promising investment opportunities have all been exploited, and so on.

Thus we have an explanation of frequent fluctuations in the level of real output or business cycles in societies with a significant degree of institutional sclerosis. This approach—the Clower-Olson approach, if I may call it that—is at no point inconsistent with any valid micro-economic theory.

Now that I have put the argument in a general equilibrium context, we must examine the fact that some prices are not determined or directly influenced by distributional coalitions, even in a relatively sclerotic economy; there is in most economies not only a sector in which disequilibria persist for long periods but also a sector where prices can never be more than momentarily out of equilibrium. If a market is not cartelized or politically controlled, workers who cannot get employment because wages or prices are too high to clear markets in the sectors under the thrall of special interests are free if they choose to move into the flexprice sector.

If they do not reflect on the matter, some economists might argue at this point that this freedom of movement will ensure that there is full employment. The hurried economist might suppose that, even in the most highly cartelized and lobby-ridden economy, so long as any sectors remain open to all entrants, there will be no involuntary unemployment.

One of the lesser problems with this argument is that it ignores the time it would take for resources to shift sectors. The sticky character of the prices and wages in the organized sector implies that the flexible prices will initially absorb the whole of any unexpected deflation or disinflation, thereby making the relative prices in the cartelized or controlled sector even higher than before. The decrease in aggregate demand and higher relative prices together imply a substantial reduction in the quantity of goods and labor demanded in the organized sector. Thus full employment could require a substantial migration to the flexprice sector. Some of the owners of unemployed resources may suppose that because of either government action or equilibrating forces any recession or depression will be temporary and then it may not pay to move to the flexprice sector. Such a move will sometimes involve considerable monetary and psychic costs; consider, for example, the uprooting of families in major cities in order that they might seek employment in the rural areas where many of the goods with flexible prices are produced. Moreover, many of the resources used in the fixed-price or disequilibrium sector will not have more than a fraction of their normal value if shifted to the other sector; factories and machines are often constructed to serve only specialized needs, and workers with considerable industry-specific or firm-specific human capital may be able to do only unskilled work for a time in other industries or firms. Some people describe themselves as unemployed if the only available work involves not only a change of occupation but a great change of status as well. And at the same time they might be too old to invest in a new skill requiring as much education, training, or service with a single firm as their prior skill. Unwillingness to invest in a second profession may be due to a deplorable conservatism in many individuals of middle age or older, but it surely often exists, and when it does, a full employment equilibrium literally could arrive only after most of those in the category at issue have retired. As Keynes wisely said, in the long run we are all dead.

Even if we take a timeless view of macroeconomic fluctuations and we unrealistically ignore the costs of the resource reallocation to the flexprice or equilibrium sector whenever aggregate demand is substantially less than expected, the fact that there are always some flexible prices need not ever insure full employment. A second problem with the hurried economist’s general-equilibrium argument is that it overlooks what can best be described as the “selling apples on street corners” syndrome.

Though we are all distressed at the thought of unemployed workers who are reduced to selling apples, the economist who knows that the economy is a general equilibrium system will realize, if he does not let his emotions overcome his powers of analysis, that an increase in the number of those selling apples on street corners represents a helpful and equilibrating response to the situation. If there is a great increase in the number of people selling apples, we may reasonably infer that that sector is not organized and accordingly has flexible prices. Thus the move of unemployed resources into selling apples is a helpful shift of resources into the flexprice sector and is symbolic of the many other such shifts that take place. This “selling apples” argument is not, I insist, a parody, but rather a correct statement of one aspect of the matter; that this is so becomes evident when we consider the loss of welfare that would occur, for consumers as well as for workers, if streetcorner vending were prohibited during a depression.