Page 1 of A Space-Traveler's Manifesto, July 5, 1958.

On August 15,1958, Freeman and Ted flew from San Diego to Pasadena to visit the U.S. Army's Jet Propulsion Laboratory at Caltech. JPL, where the Explorer satellites were being built, was preparing to launch the 143-pound Explorer 6. "The reception there was rather cool," reported Freeman. "The lady at the front office decided Taylor and I were a pair of crackpots and tried to get rid of us. After half an hour of arguing we got inside and then it all went very well."[200]

"I can just imagine the two of them showing up at a place like JPL, which was trying hard to get these little bitty satellites up and saying, 'We're here to talk about a 1,000-ton satellite powered by nuclear bombs,' " says Lew Allen, who was supervising ARPA's contract with General Atomic and later became director, under NASA administration, of JPL. Adding to the disconnect in scale between Orion and JPL, Freeman and Ted were not in Pasadena to talk about launching a satellite. They were there to discuss auxiliary vehicles that might be carried aboard Orion on its interplanetary tour. "We were beginning to look at what sort of rockets to put in the payload of the 4,000-ton vehicle for landing on Ganymede," says Ted.

"We really thought the thing was going to fly," Ted continues. "And once it flew it was no big deal to decide to go to Saturn or Jupiter, or somewhere else. And plunk down on satellites or not, because it was high thrust. We did look at backing into various-size objects including, at some point, landing on asteroids by having the last explosion be just as you were settling down on the surface." Landing the mother ship on larger objects such as Mars or Ganymede, against gravity that was even one-third or one-sixth of Earth's, was risky, both because of the danger of crashing the ship and because the landing site would be contaminated by the last few bombs. "We were environmentally conscious of some of the questions raised by landing on Io or Ganymede or whatever—bang, bang, bang, and then how about all this radioactivity? First sign that here come the humans is a whole bunch of Cesium 137 and whatnot! Neutrons first, then gamma rays. We spent a fair bit of time thinking about that."

When Project Orion's contract was signed, the largest payload lifted into orbit—Sputnik III, launched by the Soviet Union on May 15, 1958—weighed 2,926 pounds. The 4,000-ton, 2 g-acceleration Orion vehicle proposed in 1958 was intended to deliver 1,600 tons to a 300-mile orbit; 1,200 tons to a soft lunar landing; 800 tons to a soft lunar landing or a Mars orbit and return to a 300-mile orbit around Earth; or 200 tons to a Venus orbit followed by a Mars orbit with a 300-mile Earth orbit return. An "Advanced Interplanetary Ship," powered by 15-kiloton bombs, with up to 4 g acceleration and a takeoff weight of 10,000 tons, was envisioned as 185 feet in diameter and 280 feet in height. Its pay-load to a 300-mile orbit was 6,100 tons; to a soft lunar landing, 5,700 tons; to a Venus orbit followed by a Mars orbit and back to a 300-mile Earth orbit, 4,500 tons; to a landing on an inner satellite of Saturn and return to a 300-mile Earth orbit—a three-year round-trip—1,300 tons.[201]

By the time of the visit to JPL, Freeman had a specific destination in mind. Enceladus, 312 miles in diameter, is the next-to-innermost moon of Saturn, discovered by William Herschel in 1789. Its gravity is 1/200th that of Earth—enough to enable a secure landing, but with an escape velocity of less than 400 mph, making it easy to depart. Enceladus is about as dense as a packed snowball, and a long way from La Jolla—about 800 million miles, some nine times the distance from Earth to the Sun. If Earth were a billiard ball, our moon would be a marble 6 feet away; Mars a golf ball at 1/4 mile; Jupiter an overinflated beach ball at 2 miles; Saturn an underinflated beach ball at 4 miles; and Enceladus a peppercorn about 3 feet from the beach ball's surface, 2 feet beyond its hula hoop-size rings. To an observer on Enceladus, orbiting Saturn every thirty-two hours, Saturn would appear about 3,000 times the size that Earth's moon appears to us. Saturn and its rings would fill the Enceladean sky, changing phase from hour to hour, illuminated by the pale light of a distant sun.

During July of 1958, Project Orion quadrupled in size, yet the entire project group was still small enough to meet informally in Ted's office whenever a new problem or a possible solution came up. "We are about 12 altogether at this point," wrote Freeman on July 31, 1958. "It is very different from a month ago when we were three."[202] The million dollars from ARPA and the increasing involvement of the Air Force had suddenly lent credibility to Ted's ideas. "Within this first month they have spent about $40,000 and think their work output has been pretty good for this," Mixson reported after his visit on July 29.[203] To Freeman, the spaceship was "slowly taking shape and becoming more definite, like a figure being chiseled out of a piece of marble."[204] The first TRIGA reactor—as imaginary as Orion only two summers ago—had gone into operation on May 6. Orion was moving ahead almost as fast. In between calculating opacities and designing pusher plates, shock absorbers, and bomb-delivery systems, the Orion crew spent more and more time thinking about where to take the ship. "We were all champing at the bit to get on with it and get out there," says Ted. "What Orion could do was much more interesting to me than how it worked, nearly the reverse situation from my work on the bombs."[205]

"The official mission at the beginning was just Mars," Freeman explains. There was no formal mission statement as to what would be done on Mars, or why. To Air Force generals or congressmen, there was always the argument that if we did not send Orion to Mars the Russians might get there first. To the engineers, the 20 km/sec velocity required for a round trip to Mars offered a benchmark around which to design a first-generation ship. To the mission planners, Mars offered a test of life-support systems and a goal for a shakedown cruise. Freeman spoke up for science in general and biology in particular. "I think the study of whatever forms of life exist on Mars is likely to lead to enormous and unpredictable steps in understanding the mechanics of life in general, he wrote.[206]

Burt Freeman calculated expedition timetables, though warning, in Minimum Energy Round Trips to Mars and Venus, that these "approximate departure dates are by no means to be taken as exact programs for any actual flight."[207] Departing Earth during a favorable outbound period, and then waiting on Mars for a favorable return, the numbers worked out as follows: Earth to Mars, 258 days; then a 454-day wait; Mars to Earth, 258 days; for a total of 970 days or 32 months. Possible departure dates were: October 1960, November 1962, January 1965, and February 1965. The consensus was to aim for 1965. These were minimum-energy voyages; the trip could be made in less time or at different times at the expense of additional bombs. Venus could be included by abbreviating the stay on Mars. "We would have liked to fly by Venus and have a close look at it," says Freeman Dyson. "Certainly we didn't know the atmosphere was as dense and hot as we know it is now, but I think we already knew that the surface was not a possible place to visit. Also we knew that Venus has no moons, and that already made it less interesting than Mars."

In a brief appendix, Landings on Mars' Satellites, Burt Freeman noted that "the two satellites of Mars offer interesting vantage points and might be used as bases. Phobos would be particularly useful due to its unusually low altitude." Phobos is only 16 miles long, about the size of Manhattan, and fewer than 4,000 miles up. "Escape speed might be ~10 cm/sec, large enough that a person couldn't jump off."[208] If that person threw a baseball, however, it would exceed Phobos's escape velocity and never come back.

Burt Freeman was excited by the physics of Orion, but was not obsessed with personally going to Mars. "The obtaining of opacities was really our main business—this was just a little side excursion," he says. His calculations showed the advantages of Orion's high thrust. "Takeoff from Earth and departure for Mars would require 15.2 km/sec if takeoff and acceleration into the transfer ellipse are two separate maneuvers, while only 11.6 km/sec is needed if the thrust is all applied during takeoff."[209] Transit time is reduced by accelerating quickly and maintaining full cruising speed until reaching the destination, rather than accelerating slowly and having to begin deceleration long in advance.

Had Orion departed as scheduled, a landing on our own moon would have been included—at least to plant the United States flag. Mars, however, had water to support an extended stay and supply propellant for the voyage back. "We assumed that you could pick up propellant on Mars, water probably," says Freeman Dyson. "What we would have done would have been to go to the North or South Pole where there is plenty of water. It wasn't clear whether you would really want to, but landing on Mars would be much easier than landing on Earth. We wanted to make it a four- or five-year stay so that you would really explore the whole planet. I remember saying that we should be like Darwin's Beagle, which took five years."

Landing Orion on Mars, using bombs for the descent, might have been perceived as bombing a national park. More likely the ship would have remained in orbit, or used Phobos as a base, while the Martian surface was explored using chemically powered landing craft. A later mission study proposed sending multiple 4,000-ton Orion ships to Mars, landing one of them permanently on the surface to serve as a base. "This excursion would put twenty personnel on the Martian surface for a period of approximately one year. Ecology systems and supplies for two years would be provided," it was explained. "The ORION engine would be used to decelerate the vehicle down to a few thousand feet off the ground and several hundred feet per second velocity and then would be jettisoned. The separated payload compartment would then be landed by means of chemical rockets." An illustration accompanying the proposal shows "the payload compartment sitting on its shock-absorbing landing gear while in the distance some of the crew are inspecting the remains of the ORION engine." This would reduce or at least appear to reduce contamination of Mars. "For the early part of setting up the base, perhaps as many as fifty persons would be on the surface, all but twenty of them returning to the orbiting ORION vehicles by means of the landers/returners. After a stay of forty days or so, the orbiting ORIONS would return to earth leaving the twenty personnel to their tasks until the next favorable date for a trip to Mars."[210]

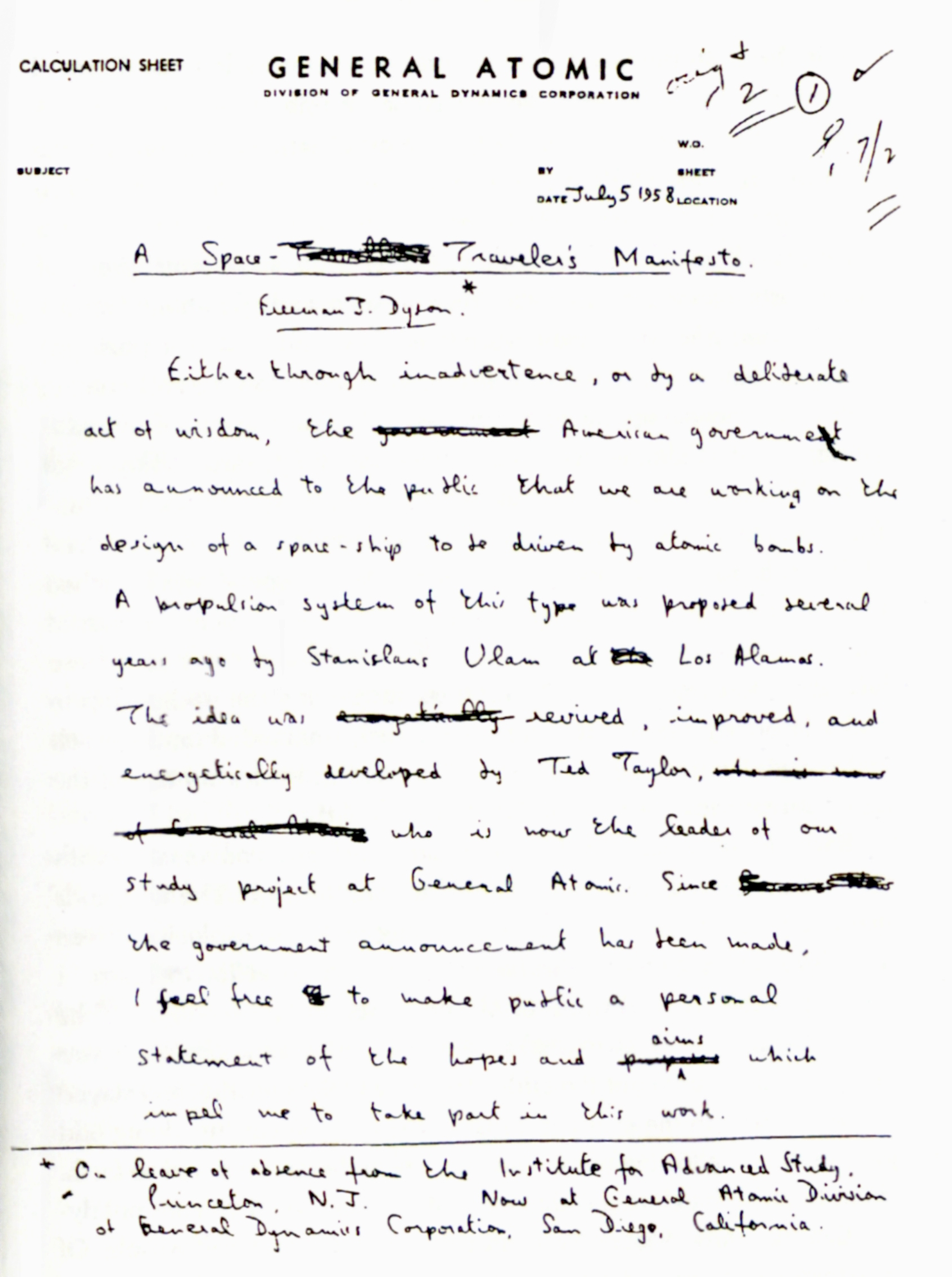

It was frustrating, for the first six months of 1958, to be making plans to explore the solar system that could not be openly discussed. The ARPA contract was signed on June 30, and a brief press release, lifting the veil of secrecy, was issued in Washington on July 2. Freeman responded by drafting A Space-Traveler's Manifesto, dated July 5, 1958:

Either through inadvertence, or by a deliberate act of wisdom, the American government has announced to the public that we are working on the design of a space-ship to be driven by atomic bombs.

It is my belief that this scheme alone, of the many space-ship schemes which are under consideration, can lead to a ship adequate to the real magnitude of the task of exploring the Solar System. We are fortunate in that the government has advised us to go straight ahead for the long-range scientific objectives of interplanetary travel, and to disregard possible military uses of our propulsion system.

From my childhood it has been my conviction that men would reach the planets in my lifetime, and that I should help in the enterprise. If I try to rationalize this conviction I suppose it rests on two beliefs, one scientific and one political.

1) There are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamed of in our present-day science. And we shall only find out what they are if we go out and look for them.

2) It is in the long run essential to the growth of any new and high civilization that small groups of men can escape from their neighbors and from their governments, to go and live as they please in the wilderness. A truly isolated, small, and creative society will never again be possible on this planet.

I think the much abused argument, "if we don't do it the Russians will get there first," has, in this case, some force. But I would wish to pursue the work with equal intensity if no Russian program of space-exploration existed. My purpose, and my belief, is that the bombs that killed and maimed at Hiroshima and Nagasaki shall one day open the skies to man.[211]

Page

1 of A Space-Traveler's Manifesto, July 5, 1958.

On June 28 the last General Atomic employees left the Barnard Street School and moved to the new laboratory site. It was an easy walk to the bluffs at Torrey Pines, where on most afternoons a strong breeze blew in from the cool Pacific as the inland mesas baked in the Southern California sun. A narrow strip of eroded upland, just north of La Jolla Farms, was home to the Torrey Pines Glider Club, an informal group of enthusiasts who shared the ownership, upkeep, and operation of a two-seater, wood-framed, fabric-covered sailplane and a war-surplus gas-powered winch. On weekends, if the wind was blowing and enough volunteers showed up, the glider was assembled at one end of an undulating, unpaved landing strip whose other end disappeared off the edge of a cliff. A signal was given to the winch operator, and then with a full-throttle roar and a smoking clutch the quarter-mile cable went taut. The glider, its handlers running beside it as it picked up speed, was launched upward at a steep angle, dropping the towline shortly before it passed over the winch at the edge of the cliff. If skills and conditions were favorable, you could glide for miles, coasting along the updrafts up to Del Mar or beyond; if you or the wind failed, you landed on the beach and the glider was disassembled and carried in pieces up one of the steep canyons that permeated the sandstone cliffs.

Early in the summer of 1958, Freeman struck up a conversation with some of the ground crew and decided to join the club. The weekends that one year later he would spend helping to fly the explosive-driven models of Orion at Point Loma he now spent gliding at Torrey Pines. "I was out in the sun and wind for eleven hours, from 8:30 till 7:30," he reported on July 13, two weeks after the ARPA announcement was made. "I came out to put the glider together in the morning and stayed to take it apart in the evening. Most of the day I spent just doing odd jobs, pulling the towing wire, wheeling the glider around, and so forth. What I like about gliding is that most of the time when you are not flying there are lots of jobs to do and it is a friendly group of people. Of course the best part of the day was the two flights. One lasted 15 minutes and the other ten. We fly up on a wire which is pulled by a winch, then let go of the wire and sail around in the wind where it rises over the cliffs. Today it was a good strong wind and we could stay up as long as we liked, with the ocean far below on one side, the yellow cliffs on the other."[212]

On August 2, after making three flights, Freeman reported that "the controls are very peculiar. One expects it to steer like a car but it doesn't. You move the control and nothing happens for about two seconds. Then it starts to turn much too fast and you have to turn it back hard the other way. I am still scared of it and that makes it exciting."[213] The lag in response time was similar to that of the control system that Freeman had recently analyzed for a two-bombs-per-second Orion: you steered the ship by shifting the position of the bombs, but had to allow a few pulse cycles for the course changes to take effect. Freeman also learned to operate the winch. "It is a fearsome machine, you have to jam down the accelerator until it screams at a certain pitch (there is no speedometer) and then let it go gradually up. I always was much more scared of the winch than of the glider. But today I gave about ten winch-tows and the pilots said they were satisfactory. So I am now 'checked out on the winch.' "[214]

The cooperative, adventurous spirit of the glider club was exactly what Freeman believed was required for the colonization of space. By summoning the courage to be winched off a cliff at 60 mph, his chances were improved of being aboard Orion when the signal was given to launch. "I had five flights and I feel better at it every time," he reported on August 16. "I am not scared as I was at first and that helps. Especially I enjoy the landings and I am beginning to be able to hit the intended spot."[215]

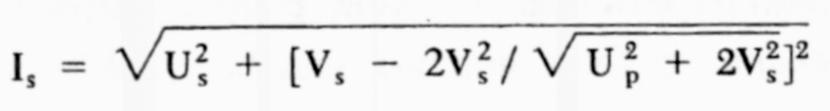

That same weekend, Freeman finished a twelve-page report, Trips to Satellites of the Outer Planets, concerning the feasibility of going to the moons of Jupiter or Saturn and back. Freeman's view of Orion's "velocity decrement to land on satellite" looks like this:[216]

"The satellites of the outer planets are the only places where we know for certain that hydrogen exists in abundance and is accessible to a spaceship," wrote Freeman in the introduction to his report. "In addition, the satellites would be able to supply unlimited quantities of the other light elements, carbon, nitrogen and oxygen, which are necessary to maintain life and also useful as propellants. The high escape velocities of the outer planets, while an obstacle to landing on the surfaces of these planets, are a great help to landing on their satellites.[217]

"The general nature of the maneuvers is as follows," Freeman explained. "The ship takes off from earth in a direction parallel to earth's orbital velocity, at a time when this will put the ship into a hyperbolic orbit intercepting the planet P. The ship approaches the planet as close as possible to its surface, and there makes a velocity-change bringing it into an elliptical orbit about the planet. The elliptical orbit is chosen so that the ship arrives at the satellite orbit tangentially. A final velocity-change at the satellite surface is required for landing on the satellite."[218]

The compelling reason to land on a satellite would be to pick up propellant. Two obvious other sources were out: the gas-giant planets are too big to land on; comets are moving too fast and too hard to find. The moons of Jupiter and Saturn looked to be the best places to stop. "They definitely do have the right stuff, and we know where they are," says Freeman. "The problem with the satellites of Jupiter is just that the gravitational field of Jupiter is so strong. So it's hard to get a velocity match, once you dive in toward Jupiter you are going so fast it is difficult to match with a satellite. So the satellites of Saturn are easier, because Saturn is not as big.

"We knew very little about the satellites in those days. Enceladus looked particularly good. It was known to have a density of .618, so it clearly had to be made of ice plus hydrocarbons, really light things, which were what you need both for biology and for propellant, so you could imagine growing your vegetables there. Five-one-thousandths g on Enceladus is a very gentle gravity—just enough so that you won't jump off."

After calculating the details for several representative trips Freeman noted, "The meaning of these numbers may be roughly summarized as follows. Round-trip voyages to satellites of Jupiter in 2 years require total velocity increments of the order of 60 km/sec. Round trips to satellites of Saturn in 3 years require total increments of 80 km/sec. For the Orion system, working at an effective exhaust velocity of 50 km/sec, these trips need mass ratios of 3.3 and 5.0 respectively. The design of the ship would have to be quite different from that of the original model which is supposed to reach 20 km/sec. with a mass-ratio of 1.5. But there seems to be no compelling reason why ships with mass-ratios of 3.3 or 5.0 should not be built."[219] Each velocity change adds a certain cost in bombs, and each bomb adds a certain cost in takeoff mass. The mass ratio is the ratio of the mass you start out with to the mass you have left when you get back. The mass ratio for an Apollo return trip to the Moon is about 600 to 1.

Freeman saw two ways to improve the situation for Orion: first, use atmospheric braking to reduce the number of bombs. A lot of fuel is consumed in slowing down when you get to Saturn, and then slowing down again when you return to orbit Earth. "It is quite likely that velocity decrements can be made by sweeping through the outer layers of planetary atmospheres without expenditure of propellant," he noted. "If this is possible, the effective velocity increment needed for a round trip is very substantially reduced."[220] The return of Orion after a voyage to the outer planets would be almost as spectacular as its launch had been three years before: approaching Earth at 30 km/sec (60,000 mph) the ship would present its pusher plate toward Earth and fire off a rapid series of bombs, changing course into an elliptical orbit that would graze the upper atmosphere in a series of fiery bursts of atmospheric drag.

The second part of the strategy is to gather propellant for the return trip at the destination, thereby reducing the average takeoff weight of the bombs. "We assume that we can use as propellant either ice, ammonia, or hydrocarbons," wrote Freeman, explaining why Enceladus was such a good place to stop. "We suppose that each propulsion unit contains one-third of its mass in the form of the bomb and other fabricated parts, and two-thirds of its mass in the form of propellant. This means that, when propellant refueling is possible, only one-third of the mass required for the homeward trip need be carried out from Earth." When you put these numbers together the end results were astonishing: "With the use of atmospheric drag a round trip to satellites of either Jupiter or Saturn could be made with a total velocity increment of the order of 40 km/sec. With refueling and braking, all the satellites become accessible with a round-trip mass-ratio less than 2."[221]

This meant that the first-generation, 20 km/sec ship designed for a shakedown cruise to Mars could easily become a 40 km/sec ship that would depart for the outer planets in a few more years. Orion's motto, "Saturn by 1970," was coined. "The Orion system, peculiarly well suited to take maximum advantage of the laws of celestial mechanics, makes possible round-trips to satellites of Jupiter in 2 years, or to satellites of Saturn in 3 years, with takeoff and landing on the ground at both ends," Freeman noted in concluding his report. "Using the outer planets as hitching-posts, we can make round-trips to their satellites with overall velocity increments which are spectacularly small. The probability that we can refuel with propellant on the satellites makes such trips hardly more formidable than voyages to Mars."[222]

"The mission was the grand tour of the solar system," remembers Harris Mayer. "But we also thought of it as a real commercial enterprise, because of the payloads you could carry. And you could bring back things from space to the earth. At that time, 1958, we were not worried about taking off from the ground. We knew how to make nuclear explosions in the atmosphere, and the characteristics are different than in space and we could take advantage of it. So it wasn't until much later that you had to get this thing up into space some other way."

"Oh, yes, he wanted to go," says Mayer concerning Freeman's plans. "I was chicken. Look, I knew enough about the space business, that this was dangerous. You had to be crazy to go. The astronauts today are very, very adventurous and brave people. But Enceladus was the one he wanted to go to then. What was remarkable is that he would come and talk to me and it was as if everything were all done."

Forty years later, Freeman and I review a two-page handwritten General Atomic calculation sheet, "Outer Planet Satellites," dating from 1958 or 1959. It lists, for nine different satellites, ten different parameters such as orbital velocity, escape velocity, density, and gravity that determine the suitability of the satellites as places to land. Freeman smiles as he carefully studies the numbers.

"Enceladus still looks good," he says.