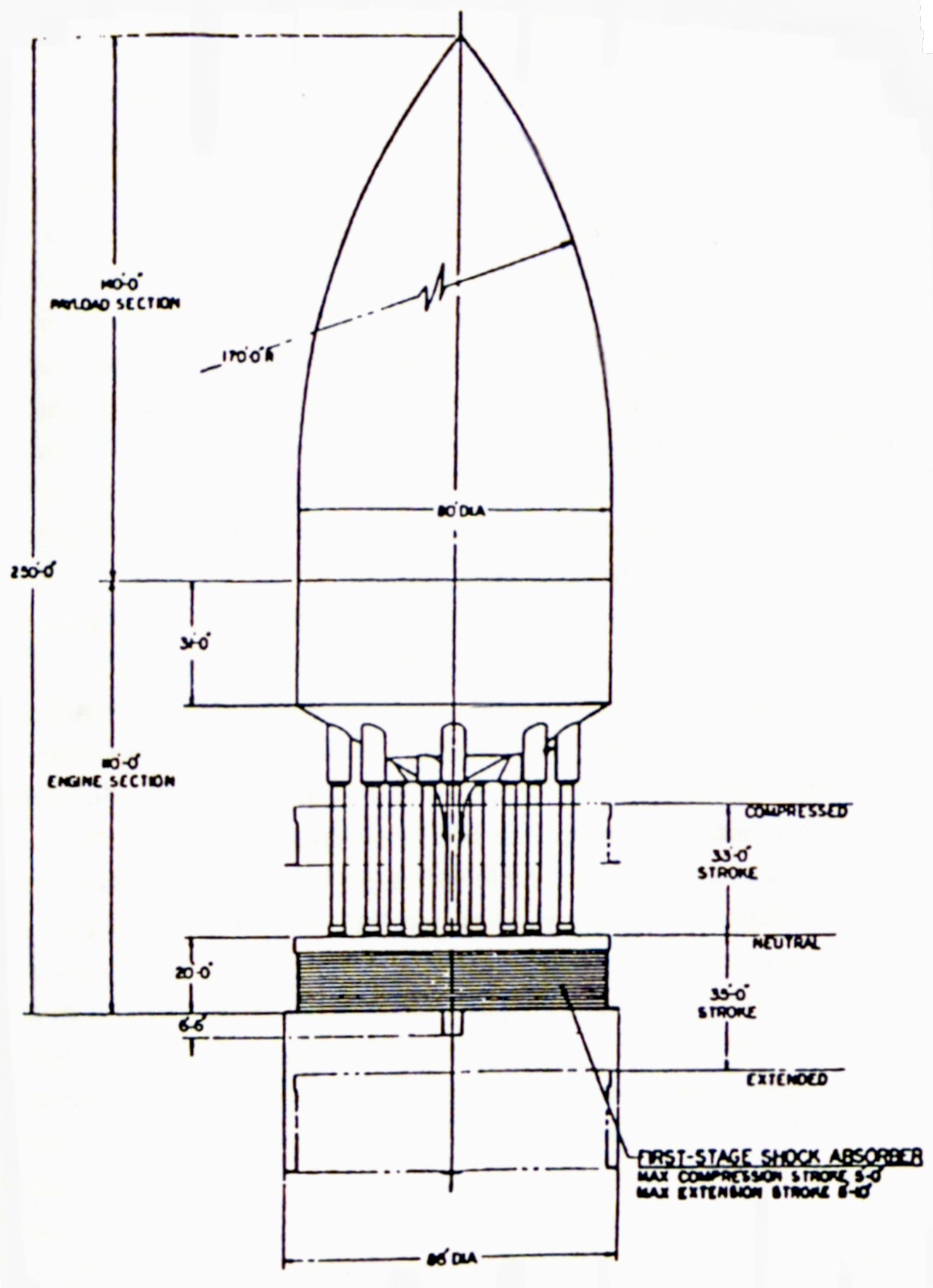

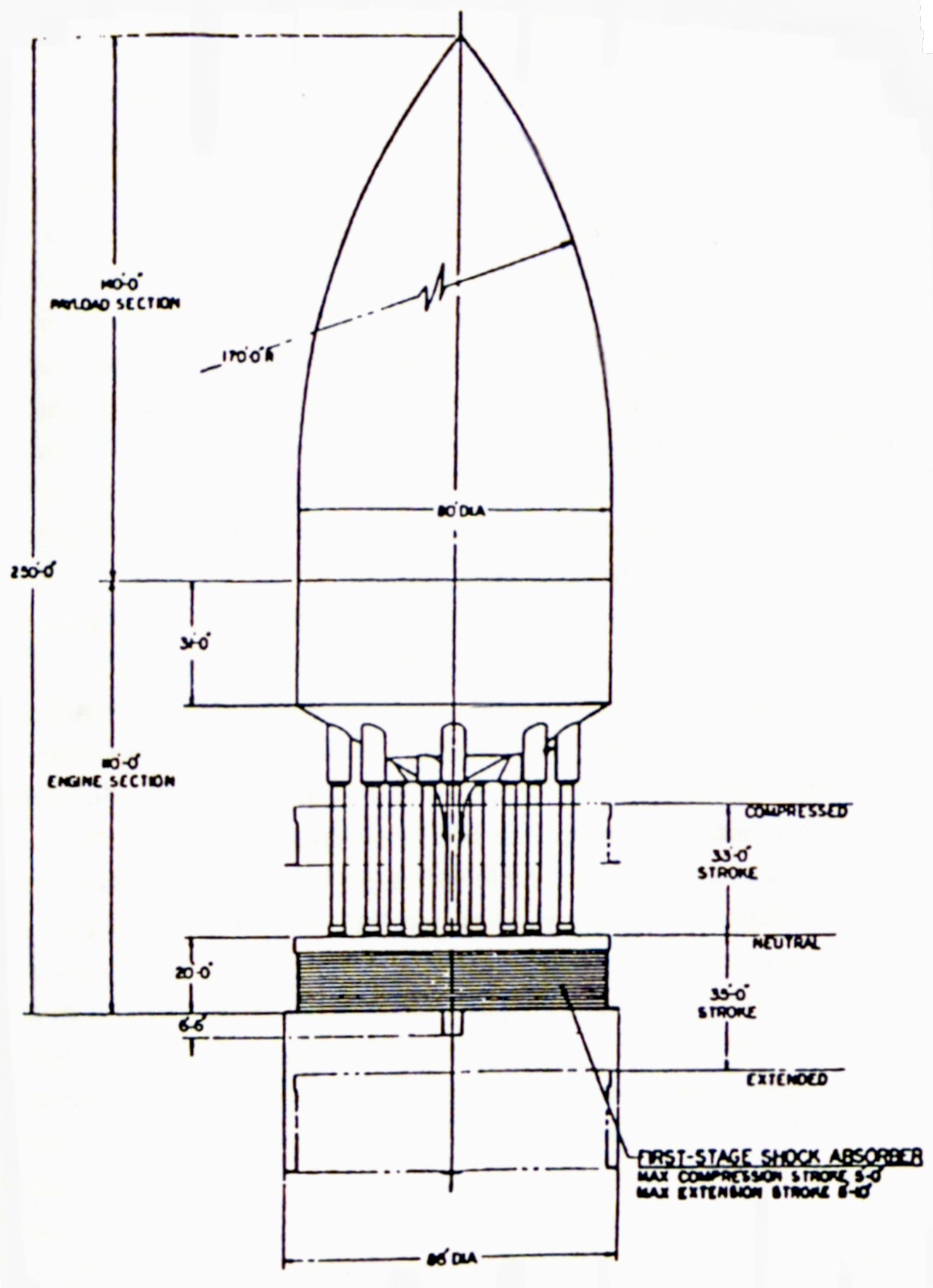

Four-thousand-ton Orion vehicle, military payload version, ca. 1962.

"From 1951 through to the atmospheric test-ban treaty, I participated in over one hundred atmospheric tests," says Don Prickett, now eighty-two and in excellent health. "We had a test series in Nevada every spring and a couple out in the Pacific every year. A test series out in Nevada might be eighteen, twenty shots. Anywhere from one kiloton to twenty, forty, fifty, something like that. I had my maximum dosage every shot, every test series. Once you hit that maximum, you didn't go near it again. I had two rads every series. Today you say two rads and people faint."

Don Prickett lives with his wife, Mary, in a log house that he and his father, a hard-rock miner and prospector, built by hand at an elevation of 7,500 feet in the San Juan Mountains near Durango, Colorado, above the trout-bearing waters of Vallecito Creek. His diet includes sourdough pancakes descended from a culture he started as a physics student in 1946. An active partner in several gold-mining ventures, he still does a little prospecting himself. "Don has always had various schemes for getting gold," says Lew Allen, his former boss at AFSWC, "hampered by two things: the price of gold has been lower for the last twenty or thirty years, and it's incredible how effective the early gold miners were."

Trained as a physicist and a prospector, Prickett worked with nuclear weapons for half a century: from uranium ore to weapons effects. "My father got quite involved in uranium prospecting," he explains. "He had a little diamond drill and he would trailer it around and poke some 100-, 200-foot holes. It was strictly radiation count with a Geiger counter, you had to get a sample of it and just see how hot it was. We found some stuff that was good, northeast of Albuquerque, but never quite good enough. All the good stuff was taken by the time we got out there looking around. At that time the AEC would jump on anything that looked good. You could count on them to help you sell it or they would buy it or tie it up."

Nuclear physics came naturally to Prickett. Not content with being a theoretician, or even an experimentalist, he wanted to tackle the full-scale development of atomic energy, firsthand. "When I was at Ohio State my biggest ambition was to get to be the test pilot on the nuclear-propelled aircraft," he says. During the 1950s, before returning to Albuquerque to succeed Ed Giller as director of research at AFSWC, Prickett worked on nuclear R&D out of the Pentagon. "Anything nuclear came across my desk," he explains. "If it didn't fit under blast, radiation or thermal, if it was effects on aircraft or effects on ships, or anything else, those were all my projects. I was the program director of them. I was there at the big one on Bikini." This was Castle Bravo, the first test of a solid-fuel, room-temperature, "deliverable" hydrogen bomb. Exploded on February 28, 1954, it yielded 15 megatons, almost three times what had been expected, producing a fireball more than three miles across.

"I had seen up until that time maybe fifty shots at least, atmospheric shots out at the test site, so I wasn't really startled," says Prickett, describing how, with Navy Captain George Malumphy, he maneuvered a remote-controlled merchant ship into the path of the bomb's fallout to test an automatic washdown system being developed for decontamination of surface craft. "I knew it was going to be big, but Malumphy and I were at least thirty miles from ground zero. And so when the order came on for countdown we put on our dark goggles. And sure enough it went off and it was a full two minutes anyway before we took off our goggles and then it was so awesome that all Malumphy could say was, 'My God, my God, my God!' "

The AEC set off the bombs, while the Department of Defense did their best to gain as much weapons-effects information as possible from every shot. Most of his projects, says Prickett, "were AEC development tests in which we hung on to get anything we could." Prickett's group chose another shot in the Castle series to test the structural response of a B-47 bomber to blast, by flying the aircraft dangerously close to where the bomb was scheduled to go off. "The AEC was just nervous as hell about us playing around out there on these shots with aircraft anywhere near them," he recalls. "They couldn't stand the publicity of having an accident so they were very, very conservative. We had done all the previous theoretical work and static testing on the B-47 at Wright Patterson and wanted to put it into position to get about eighty percent of design limit load for the blast effect. And so the project was approved even though the AEC was very unhappy about it. When it came time to position the aircraft, the AEC was in control of the safety end of it, and the trigger on the shot. We had a racetrack pattern set up with a radar control and checkpoints, so you know exactly where you're going to be within a second or so. When we came down to the final approval on it, before shot time, the AEC balked and said, 'You're too close. We don't believe your calculations, you're going to have to back off.' We said that will give us only fifty percent of the load, that ruins the project. And they said we don't care, that's all you are going to get. We didn't say anything, we said OK, and went back to talk to the test pilot who was flying the airplane. He knew how much work had gone into this. And he said, 'I'll take care of it. Don't worry. I'll take care of it.' After he hit his last checkpoint, he poured the coal on and got up into position where we wanted to be. And we got what we were after. But the AEC never knew about that."

In the spring of 1958, General Atomic s proposal for a bomb-propelled spaceship was hand-carried to the Pentagon by Ted. This was the only place, besides the AEC, where a project involving thousands of nuclear bombs could be discussed. "I received the initial proposal when I had the nuclear desk in B&D in the Pentagon," says Prickett. "I met Ted when that proposal came in. It was not very detailed, conceptual, as I remember, but enough to get our attention." The concept did not appear crazy to Don Prickett. In the overall spectrum of nuclear weapons effects, lifting 4,000 tons of Orion into orbit above a series of kiloton-yield explosions might not be too great a stretch. "It's one of those potentials that never got to its potential," he says. "We were all excited. We thought we had something that would eventually be something, but it wasn't politically correct. Everybody knew that it was reaching out, but that's the only way you can make big steps."

The Pentagon's problem was how to justify sponsorship of Orion in the absence of a specific military requirement for sending thousand-ton payloads into space. In anticipation of NASA, the distinctions between military and civilian space programs were being drawn. "It was a very long battle inside the White House as to whether the space program, post-Sputnik, was to be a civilian program or a military program," says Bruno Augenstein. "The majority vote went with NASA at that time, but it was a very complicated era. You had General LeMay calling for the Air Force to run the total national space program. At one time the Air Force proposed to form an interplanetary expedition force. That's how adventurous they were. Those were exciting times!" Assigning manned space exploration, on the scale of Orion, directly to the Air Force was politically untenable in 1958. The United States Army, with friends in high places, feared only one thing more than finding Soviet cosmonauts on the Moon: finding that the United States Air Force had arrived there first. The Army had relinquished nuclear weapons to the AEC in 1946; getting them to give up Wernher von Braun and his manned space program to NASA was still two years away in 1958.

ARPA's sponsorship of Orion assigned interim management to the Air Force, while reserving a seat at the head of the table for NASA, expected to step in and take the lead once its mandate from Congress was defined. When NASA support for Orion failed to materialize, the Air Force assumed responsibility by default. As ARPA's role in space was brought to a conclusion, toward the end of the Eisenhower administration, by Herbert York, military missions went to the Air Force and peaceful missions to NASA. Orion was caught in between—because of the bombs. "The situation of ARPA was reminiscent of the partition of Poland between Prussia and Russia in the 18th century," Freeman later explained. "Taylor's efforts to interest NASA in Orion during this period met with no success."[223] As Ted describes the predicament: "The Air Force people knew about nuclear weapon design in a lot of detail. NASA didn't understand the workings of Orion at all."

Four-thousand-ton

Orion vehicle, military payload version, ca. 1962.

Just as Ted had reassured his mother before going to work at Los Alamos that he would not be building weapons, Freeman reassured his mother, when taking the job at General Atomic, that Orion was not a warship, despite the bombs. "We are happy that we shall be under strictly nonmilitary auspices," he wrote from La Jolla in May 1958. "Luckily the military are so far quite convinced we are crazy, and we are not trying to alter this opinion."[224] Although this was true at higher political levels, the Air Force physicists in Albuquerque were enthusiastic supporters from the beginning and stayed with Orion until the end. The ARPA-funded contract was written up by the Air Force Research and Development Command, with day-to-day monitoring assigned to AFSWC, where it soon ended up in the hands of Air Force officers like Lew Allen, Ed Giller, and Don Prickett. "We nicknamed it 'Putt Putt,' " says Ed Giller. "Which always made the more formal types make a face."

Under AFSWC's auspices, the search was on for military applications that could justify advancing from a million-dollar feasibility study to the tens of millions it would take to begin development, starting with nuclear tests. The first place to go for long-range thinking on Air Force questions, in the late 1950s, was RAND, "a refuge for people who didn't get on with the establishment," as Freeman says. "The prospects of studying the military applications of a space vehicle with a payload of the order of magnitude you suggested certainly stimulated the interests of several people on our research staff," answered RAND in response to a request to suggest possible missions, "since the payload of the vehicle involved is about two orders of magnitude larger than any we have seriously considered in the past."[225] RAND reviewed Orion periodically over the next few years, and although generally enthusiastic about its technical feasibility, were never able to identify any immediate military requirement for anything that large. Unfortunately for Orion, RAND's analysts were well informed on the details of two secret programs—satellite reconnaissance and thermonuclear ICBMs—whose success would make the need for a manned surveillance or retaliatory platform obsolete.

"We have to face some kind of a moral or ethical problem, in deciding whether to lean for support mainly on the Air Force or on NASA," Freeman wrote in May 1959, as the first year's funding from ARPA came to an end. "The Air Force is naturally interested in our ship mainly as a military weapon, while NASA is supposed to be interested in scientific exploration. So ideally we ought to be working for NASA and avoiding the Air Force. However, in practice the issue is not so simple. Firstly, there is no doubt that as soon as our ship flies at all, both the Air Force and NASA will insist on having one; so it does not really make that much difference who pays for the initial development. Secondly, the Air Force is much less bureaucratic, and generally easier to work with. So we decided at least for the time being to stick with the Air Force. I think this was a wise decision. To imagine that a space-ship of this kind could be built without any military consequences would be only self-deception. Of course we are all sorry the military aspects have to come into the picture. But that is the way things are."[226]

Unlike the Apollo ships that carried astronauts to the Moon, Orion was an all-purpose, reusable craft. The same underlying vehicle could serve as merchant ship, research vessel, reconnaissance platform, orbital command center, or battleship, as circumstances changed. Possible military applications began with Freeman's original suggestion that "to have an observation post on the moon with a fair-sized telescope would be a rather important military advantage for the side which gets there first," and grew more ambitious, and at times implausible, from there.[227] "Space platforms should be examined also, as well as the movement of asteroids and the like," suggested Lew Allen in October of 1958.[228]

"After NASA was formed, the Air Force had to justify supporting Orion on the grounds that it had military significance," says Ted. "So I spent a lot of time thinking about that and really got carried away, on crazy doomsday machines—things like exploding bombs deep under the Moon's surface and blowing lunar rocks at the Soviet Union. There were versions of Orion in which the entire retaliatory ICBM force was in one vehicle, which was very hard, and any time anyone tried to fire at it, it would turn around and present its rear end at the bombs coming at it. We were doing something for the project that we didn't want to do but had to to keep it alive, we thought."

"In the early days of the project," remembers Pierre Noyes, "Freeman and Ted talked about whether it would have been wiser to sell NASA on the project and have it under civilian auspices from the start. It was clear that the main payoff would be in space exploration rather than military applications. But they were eager to get ahead with it and accepted Air Force sponsorship, which was available right away. In my view, their Faustian bargain had unfortunate consequences. Some horrendous projects came up as possible military missions. I even did a minor calculation about whether one of them would destroy the ozone layer. But, to my knowledge, neither Freeman nor Ted turned their minds to a serious search for a military mission. Had they done so, and knowing their talents, I suspect that they might have saved the project at the cost of an even more Faustian bargain."

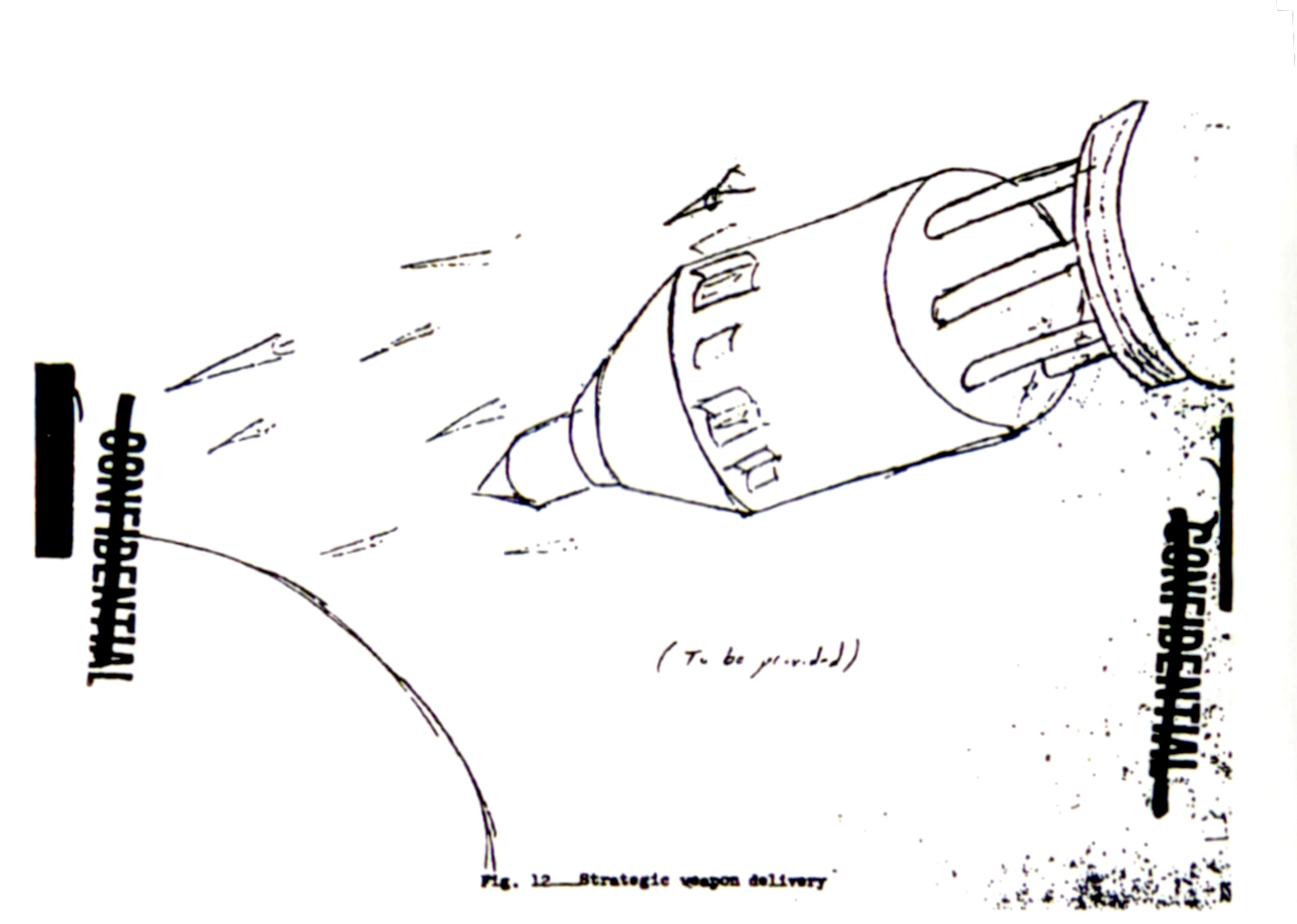

Multiple

independently targeted warheads are launched by a 4,000-ton Orion

vehicle that

has de-orbited from its station in deep space and entered a hyperbolic

Earth-encounter

trajectory to perform a retaliatory strike.

A May 1959 Air Force briefing revealed some "possible military uses of the Orion Vehicle," including reconnaissance and early-warning, electronic countermeasures ("possible to get a terrific number of jammers over a given area"), anti-ICBM ("possibility of putting many early intercept missiles in orbit awaiting use"), and "ICBM, orbital, or deep space weapons—orders of magnitude increase in warhead weights— clustered warheads—launch platforms, etc." Finally, there was "The Horrible weapon—1,650-ton continent-buster hanging over the enemy's head as a deterrent."[229] It was this possibility that came to the attention of Noyes.

In the 1950s, it was easy to build arbitrarily large, powerful hydrogen bombs, but difficult to build small ones. Exceptionally large bombs, however, inflicted diminishing returns, since immediate damage by blast and radiation is governed not only by the size of the bomb but by the distance to the horizon of the curving Earth. When the Soviets exploded a 58-megaton bomb in 1961 it raised concerns that a bomb this large "just blows a hole out of the atmosphere and you lose most of the explosive force," says Noyes. "But with a platform that could lift enormous weight, like Orion, you could go up high enough, and have a big enough explosion, to irradiate an enormous area. Because this would be above the ozone layer, you would think that the ultraviolet wouldn't get through. Well, you actually burn through the ozone layer, with the scale they were talking about. So then the question is, what happens to the ozone layer? That was why for a long time I wasn't worried about the ozone layer, because it was easy to show that it gets reestablished within a minute. Take it out, and it reforms again. It's very stable, if all you have are the constituents that are there naturally. What changes the picture completely are the chain reactions that the various industrial products make. But that's a more recent realization. That horrendous gadget would get through it, but if it was a cloudy day, it wouldn't be very good. It wasn't much of a weapon as far as I could see."

"There was a lot of controversy about that," remembers Ted, "not just whether the doomsday bomb payload for Orion was a good idea to think about, but technically, whether energy emitted by explosions in space would convert to high temperature by impact with the upper parts of the atmosphere and then reemit that energy at frequencies with a long range that would then hit the surface. There were people who argued that this was not possible. But there clearly are ways of designing the bomb in such a way that a substantial fraction of the energy that intercepts the earth strikes the surface as light and heat. The simple summary was that something on the scale of the payload that we visualized for the 4,000-ton vehicle could destroy half the earth. That was not viewed with enthusiasm by anybody that I can remember, but it was an interesting outer limit. It would play hell with the upper atmosphere. At that time—and I think now—people really had no good basis for figuring out what it would do."

Such thoughts were difficult to repress. "It was part of the addiction," says Ted. In his personal journal he noted: "Spent most of the day discussing effects of very high altitude, big explosions. George Stuart's IBM 704 code for calculating the thermal energy delivered to the ground is generally agreed to have the correct physics in it."[230] And three days later: "Had vile thoughts in the evening about how to use antimatter for wiping out populations. Perhaps someone should write a book called 101 Ways to Eliminate the Human Race and call it quits."[231]

The problem was how to distinguish the defensive from the offensive when deploying weapons in space. "Only delicate timing would determine whether satellite neutralizations were offensive or defensive," explained a secret telex on "Global Integration of Space Surveillance, Tracking, and Related Facilities," marked "For Eyes of the USAF Only," from the commander in chief of the Strategic Air Command in Omaha, Nebraska, on May 31, 1959.[232] Beyond the Moon, science would take the lead, but this did not preclude a role for the Air Force in deep space. "There presently exist no military requirements beyond cislunar space," a classified Air Force summary admitted in May 1959. "However, one must note that one reason there are no military requirements for a deep space vehicle is simply that no one has ever before seriously considered sending a large, manned, useful payload to this area for military purposes."[233]

This was not necessarily at odds with the nonmilitary goals of Freeman and Ted. "Because the Air Force was paying for it, we assumed we would have some military people on board," says Freeman. "But it would be as they do in the Antarctic when the Navy runs the Antarctic logistics for the science that's done there. It doesn't mean that the Navy does the science but they have a lot of Navy people around. So we expected it would be like that; Ted would have been the chief scientist, with some Air Force officers responsible for the operation of the ship."[234]

One of these officers would have been Captain Donald M. Mixson. "Mixson was an enthusiast. He'd have been the first man on board," says Don Prickett. Mixson and Prickett saw Orion as a way to sustain the type of creative, fast-moving effort that the proliferation of peacetime bureaucracy was bringing to an end. "Mixson and Prickett were fed up with the Air Force system and Orion was a way to put a burr under the Air Force saddle blanket," explains Brian Dunne. Mixson shuttled back and forth between Albuquerque, Washington, and La Jolla, giving endless briefings in support of Orion, and becoming the leading advocate for an Orion Deep Space Force.

Mixson, who wanted to help the physicists do physics and the engineers do engineering, instead spent much of his time fighting the bureaucracies that kept getting in the way. A typical difficulty, at the beginning of the ARPA contract, was how to get Orion documents that had been created while the project was under the auspices of the AEC transferred to Department of Defense custody, without physically sending the documents back to AEC headquarters, and then to Department of Defense headquarters, leaving the Orion scientists without access to their own work. "This was supposed to be impossible to accomplish this way until I agreed to personally sign for the documents," Mixson reported. "Solving this ridiculously simple problem took the best part of the 30th. Now I own the documents and have them out to GA on hand receipt. It is a continual source of amazement to me that technical types can move mountains but administrative people stumble over mole hills."[235]

Captain Mixson was devoted to weaving and painting in his spare time. "We had drinks or dinner at his house in Albuquerque quite often," says Ted, "and as soon as he got home, he would start weaving because most of the time he was angry at what had happened during the day, and he'd found that the way to relax was to weave as fast and furiously as he could." Mixson bent some regulations but adhered rigidly to others. Carroll Walsh once found a plastic bottle shaped like the still-secret 4,000-ton design. "I thought, holy smoke, there's the Orion! So I just sat it on my desk and never made any comments about it or anything like that," says Walsh. "And one time Mixson came here and saw that thing and had a fit! 'Oh! You, with a Q clearance! Wow! How could you do that?' And he took it home with him! He probably still has it, the hound dog!"

Mixson intermediated between the physicists in La Jolla who saw Orion as a way to visit Mars and the generals in Washington who saw Orion as a way to counter the Soviets on Earth. "Mixson was the point man on application, with Strategic Air Command and Air Research and Development Command," explains Don Prickett. "He was a tireless worker and stayed very close to SAC in terms of future system concepts." One of them was the deployment of an Orion fleet. Military Implications of the Orion Vehicle appeared in July of 1959 and was, according to a declassified Air Force summary, "largely the work of Mixson, aided by Dr. Taylor, Dr. Dyson, Dr. D. J. Peery, Major Lew Allen, Captain Jasper Welch, and First Lieutenant William Whittaker. The study examined the possibilities of establishing military aerospace forces with ORION ships and these were conceived as: (1) a low altitude force (2-hours, 1,000-mile orbits), (2) a moderate altitude force (24-hour orbits), and (3) a deep space force (the moon and beyond). The report recommended that the Air Force establish a requirement for the ORION vehicle in order to prevent the 'disastrous consequences' of an enemy first."[236]

Mixson gave four separate briefings on military applications of Orion, over just three days in July of 1959: "7 July: Briefing to ARDC staff personnel—about 20 people and a private meeting with General Davis. 8 July: Briefing to USAF Air Staff—about 50 people. 9 July: Briefing to Gen. Demler and his immediate staff. Briefing to AFCIN, about 25 people from Directorate of Targets, etc. They will poke around in USSR for indications that USSR is working on this."[237] No evidence of a Soviet Orion program turned up, but this did not dampen the enthusiasm of the Strategic Air Command. General Thomas S. Power, who had succeeded Curtis LeMay as SAC's commander in chief, initiated USAF QOR's (Qualitative Operational Requirements) for a "Strategic Aerospace Vehicle," a "Strategic Earth Orbital Base," and a "Strategic Space Command Post" with Orion in mind. Don Prickett flew out to General Atomic with Mixson for a briefing with General Power. "It was a wide-open discussion on potential and what we were going to do with it when we got it," says Prickett. "And Power of course didn't have any problem knowing what to do with it."

By 1960, the world's nuclear stockpile was estimated by John F Kennedy at 30 million kilotons, whose primary mission was to deter a first-strike attack. Orion offered an alternative to keeping all this firepower—some ten thousand times the total expended in World War II—on hair-trigger alert. Mixson's original study has yet to be declassified, but a later, anonymous General Atomic report on potential military applications of Orion appears incorporate his description of the Orion Deep Space Force:

Once a space ship is deployed in orbit it would remain there for the duration of its effective lifetime, say 15 to 20 years. Crews would be trained on the ground and deployed alternately, similar to the Blue and Gold team concept used for the Polaris submarines. A crew of 20 to 30 would be accommodated in each ship. An Earth-like shirt sleeve environment with artificial gravity systems together with ample sleeping accommodations and exercise and recreation equipment, would be provided in the space ship. Minor fabrication as well as limited module repair facilities would be provided on board.

On the order of 20 space ships would be deployed on a long-term basis. By deploying them in individual orbits in deep space, maximum security and warning can be obtained. At these altitudes, an enemy attack would require a day or more from launch to engagement. Assuming an enemy would find it necessary to attempt destruction of this force simultaneously with an attack on planetary targets, initiation of an attack against the deep space force would provide the United States with a relatively long early warning of an impending attack against its planetary forces. Furthermore, with the relatively long transit time for attacking systems, the space ships could take evasive action, employ decoys, or launch anti-missile weapons, providing a high degree of invulnerability of the retaliatory force.

Each space ship would constitute a self-sufficient deep space base, provided with the means of defending itself, carrying out an assigned strike or strikes, assessing damage to the targets, and retargeting and restriking as appropriate. The space ship can deorbit and depart on a hyperbolic earth encounter trajectory. At the appropriate time the weapons can be ejected from the space ship with only minimum total impulse required to provide individual guidance. After ejection and separation of weapons, the space ship can maneuver to clear the earth and return for damage assessment and possible restrikes, or continue its flight back to its station in deep space.

By placing the system on maneuvers, it would be possible to clearly indicate the United States' capability of retaliation without committing the force to offensive action. In fact, because of its remote station, the force would require on the order of 10 hours to carry out a strike, thereby providing a valid argument that such a force is useful as a retaliatory force only. This also provides insurance against an accidental attack which could not be recalled.[238]

"Such a capability, if fully exploited, might remove a substantial portion of the sphere of direct military activity away from inhabited areas of the opposing countries in much the same manner that seapower has," another General Atomic study concluded, echoing the argument that had struck such a responsive chord at SAC.[239] Mixson, according to Freeman Dyson, "had read Admiral Alfred T. Mahan's classic work, The Influence of Sea Power upon the French Revolution and Empire, and his imagination had been fired by Mahan's famous description of the British navy in the years of the Napoleonic Wars: 'Those far distant, storm-beaten ships, upon which the Grand Army never looked, stood between it and the dominion of the world.' "[240] Lew Allen, later chief of staff of the Air Force, remembers Mixson's Deep Space Force as "a very imaginative battle group in the sky idea, with these things running around," and admits that "somewhere in there I began to think we were losing touch with reality." Was it crazy to imagine stationing nuclear weapons 250,000 miles deep in space? Or is it crazier to keep them within minutes of their targets here on Earth?

"Orion would be more peaceful and probably less prone to going off half-cocked," says David Weiss, the aeronautical engineer and former test pilot who shared Mixson's enthusiasm for Deep Space Force. "We were looking at a multinational crew, the same sort of thing that's going on in NATO, and we would have had safeguards—a two-or three-key system in order to launch anything." The deterrent system we ended up with, instead, depended either on B-52 crews kept under constant alert, or on young men stationed underground in silos, or underwater in submarines, waiting, in the dark, for a coded signal telling them to launch. "At SAC, this was always the weak point," continues Weiss. "You were sitting there listening to your single side-band and it would come through either on a cell-call frequency, which is assigned to you, or on a barrage broadcast, and it would tell you to open up your target packets." There were about twenty minutes available to verify the extent of an enemy attack—or false alarm—before launching an irrevocable response. The threat was tangible. "I went to Vandenberg Air Force Base with Brian Dunne," remembers Jerry Astl, "and they invited me to go into the launching silo, with a Titan intercontinental missile sitting there with three nuclear warheads on it, waiting for a launch code. We went into the silo and could actually pet that damn sucker."

Instead of living underground like prairie dogs in North Dakota, or incommunicado in submarines, the Blue and Gold Orion crews would have spent their tours of duty on six-month rotation in orbits near the Moon—listening to 8-track tapes, picking up television broadcasts, and marking time by the sunrise progressing across the face of a distant Earth. With one eye on deep space and the other eye on Chicago and Semipalatinsk, the Orion fleet would have been ready not only to retaliate against the Soviet Union but to defend our planet, U.S. and U.S.S.R. alike, against impact by interplanetary debris.

Once Orion ships were in deep space orbit, the outer planets would be within easy reach. The temptation would have been impossible to resist. "When you would go out privately with people in the Air Force, here in La Jolla, and talk about what's Orion for, it was to explore space, no question about that," says Ted. The '60s might not have become "the sixties" had events unfolded as envisioned by Mixson and Prickett. The '50s might have just kept on going, thanks to Deep Space Force.