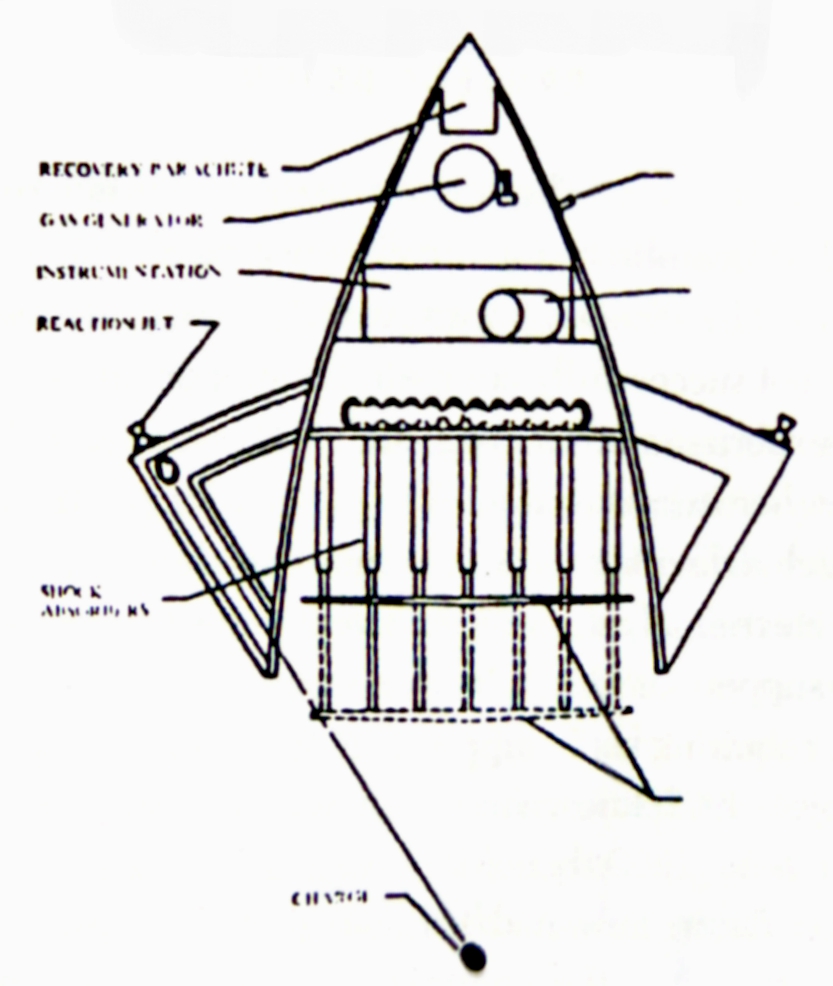

Twenty-ton test vehicle: 21 feet in diameter; 35 feet in height, number of charges, yield, and date unknown.

"General Atomic has chosen to cling firmly to the concept of a manned ship," Lew Allen noted in October of 1958.[241] The thinking at the time was to launch from an armored barge out at sea, after some initial tests in an isolated area of the Nevada Test Site known as Jackass Flats. "The general idea was to have people on board all the time," Freeman remembers. "I think forty was the standard number. It was like a submarine, with three men for each job. There certainly would be tests involving a few bombs, maybe going up a couple of miles, but if you wanted a full-scale flight then you might as well go the whole way."

"We assumed it would be somewhere near La Jolla in the Pacific," Freeman answers, when asked about the location of the launch. "The bombs in the beginning were fairly low yield. The barge would have to be built like a battleship, but you want it to stay afloat." The ascent into orbit would be under automatic control, with no intermediate course to choose from, during those initial six to eight minutes, between straight up or aborting the flight. "The latest steering scheme for the full-scale vehicle," Second Lieutenant Ron Prater reported in April 1959, "is to place a chemical rocket at die very nose of the ship, mounted so that it will rotate to point in any direction perpendicular to the main axis of the ship."[242]

Once Orion was out in space, its navigators would plot the ship's current position and calculate future maneuvers and course corrections in advance. "That's what you needed these forty guys for," explains Freeman. "They would have been using a sextant and working out the navigation on graph paper." Among the surviving Orion documents are hundreds of pages plotting optimum trajectories for high-thrust Earth orbit maneuvers, Mars visits, Jupiter and Saturn encounters, satellite rendezvous missions, and lunar colony support—all worked up by hand on light-green Keuffel & Esser graph paper. Orion would be steered by the stars.

In September of 1959 it was decided to bring someone on board to start thinking about test flights, and that person was aeronautical engineer David Weiss. "They were looking for someone with a background in flight testing," he remembers. "And I was a little misled in that I believed Freddy de Hoffmann had a very short time scale. They were talking about flying it in two or three years. I've been into flight-test projects where, on an experimental airplane, we knew even three or four years ahead of time what it was going to look like, enough for them to start building simulators for us to fly. So, that's what I had looked forward to. Hopefully I would have flown the damned thing."

Weiss is a third-generation military pilot, born in 1929. "I lied about my age for the Air Force," he explains, "and wound up getting some B-29 experience in World War II." His uncle flew B-17s. His father, later a pilot for Luddington Airlines, trained in the U.S. Army Air Service under Billy Mitchell, who led an armada of nearly 1,500 airplanes in World War I. After the war Mitchell argued so vehemently for an independent Air Force that he was court-martialed for insubordination in 1925. David Weiss's grandfather had worked for the other side in 1918, flying giant Riesenflugzeuge, or R-planes, four-engine metal bombers that could carry up to 4,000 pounds of bombs. "They bombed Paris from just over 20,000 feet," says Weiss. "The Allies couldn't reach them in the fighters. They had electrically heated flying suits, and they had oxygen, but not enough, so that on the way in to the target, the bombardier had the oxygen and on the way back, the pilot had the oxygen because he had to land the airplane. They were bombing the Paris rail yard and doing it in a very civilized manner by calling the French over the telephone and telling them at what time they would arrive.

Weiss believed in Orion not only as a retaliatory deterrent, but as a boost-phase anti-ballistic missile shield. "You could park several of these ships in orbit," he says, "and from there, the propulsion and dynamics looked excellent, in terms of knocking things down. The atmosphere was working with you rather than against you, because you could see stuff coming up. You'd do it with depleted uranium rods, to just simply shred them, or use high explosives, and whatever didn't collide with an ascending ICBM would then hit the atmosphere and burn up. It really was a much better way to do ABM, there's no question about that."

After graduate school, Weiss took a job test-flying Convair B-36 bombers, the six-engine, propeller-driven monsters that served, briefly, as the means of delivering first-generation, 42,000-pound hydrogen bombs. Later retrofitted with an additional four jet engines, the B-36 had a wingspan of 20 feet greater than a Boeing 747 and could cruise at 50,000 feet. "Some of the heavy takeoffs we did were at an unheard-of over 500,000 pounds—that's 250 tons, and starting to approach Orion size," he explains. "We did fifty-hour flights, which would take us 10,000 miles easily, and would have reached any target of interest at that time. Going out of a place like Thule that's a round-trip to almost anywhere—assuming Thule was there when you got back." Weiss then taught aircraft and missile design at the University of Michigan, and in 1959 he followed his colleague David Peery to General Atomic. "Peery couldn't really describe Orion, but he said 'It'll do for us in the space age what the B-36 is doing right now.' And that's what clinched it in terms of coming to San Diego," says Weiss.

Project Orion's plans, at the end of 1958, were to start off by launching a 50-foot-high, dome-shaped, 50- to 100-ton unmanned "recoverable test vehicle," with a 40-foot-diameter pusher plate, propelled to an altitude of 125,000 feet by 100 to 200 explosions ranging from .003 to .5 kiloton in yield. An "orbital test vehicle" was to weigh 880 tons and would be 80 feet in diameter and 120 feet in height, propelled into a 300-mile orbit by 800 bombs of .03 to 3-kiloton yield. This trial-sized Orion was still estimated to be capable of carrying 80 tons to Mars orbit with a 300-mile Earth-orbit return. By the end of the first year it was evident that the leap to 50- and 880-ton test vehicles was too ambitious and "a step by step progression to the full scale 4,000-ton vehicle" was in the works.[243] The first step, as proposed to ARPA in the spring of 1959, would be "a small scale model with a pusher about 10 feet in diameter and the whole model weighing about 5 tons. The model would be taken up to high altitude by airplane or balloons in order to reduce drag effects where it would be released. Propulsion would be by a few high explosive shots culminating, perhaps, in 3 or 4 very small atomic shots."[244] Plans called for launching this model by June 1960. The next step would be an unmanned 40-foot-diameter model weighing 400 tons, "which will carry a useful payload of 60 tons into orbit using 500 one-hundred-ton atomic shots."[245] This was scheduled for completion early in 1962.

The first million dollars from ARPA was set to run out on May 30, 1959. "Ted Taylor and I will now spend a week doing battle for our project," Freeman wrote while flying from San Diego to Washington on April 26, 1959. "We shall see various potentates in the Air Force and the Government. They may (a) cut off the funds when our contract expires next month, (b) continue as we are with a gentle expansion, or (c) decree a major and rapid expansion. We shall argue for (c) and hope to get (b)."[246]

They got (b). At the final briefing on April 30, 1959, AFSWC and General Atomic jointly requested an additional $5,600,000 to continue the project for another year. According to Mixson, this "reflected the high level of confidence and enthusiasm in the workability of the propulsion concept and a feeling of urgency that grew out of the dawning knowledge that this project was of great and immediate—if not decisive—importance to the nation's defense effort. The feeling was bolstered by the release to the press of the capabilities of the propulsion scheme, which suggested that if other nations were not already interested in this concept they soon would be."[247] ARPA granted an additional $400,000 to sustain the project through September 14, 1959. During this period there was intense debate in Washington over how ARPA's space activities would be divided lip, and to what extent Orion would play a role in space exploration and defense.

"The people in Washington sent down a committee of inquisitors to find out if our claims for this space-ship are technically sound," Freeman reported from La Jolla on July 4, 1959. "We spent a lot of time answering their questions and arguing with them. They seemed quite favorably impressed. But Washington will not make up its mind what to do about us until August."[248] The political arguments remained unresolved. Committing the Air Force to a large manned space project would alienate both NASA, who had already been promised the Moon, and congressional critics looking for evidence of Pentagon excess. Yet there were equal political liabilities to committing NASA, should they accept custody of Orion, to a project involving so many bombs. There were good reasons for just letting the whole thing drop. Since Orion had friends in high places the project was kept on life support.

At the end of July, Lew Allen flew to Washington to argue in favor of Orion before the propulsion panel of the Air Force Scientific Advisory Board. "ARPA has about decided to proceed at $120k/month," he reported. One of the objections under consideration by the advisory board was that since Eisenhower had committed the United States, unilaterally, to a moratorium on all nuclear tests as of October 31, 1958, there was no point proceeding with Orion as long as the moratorium was in effect. "I believe this is a little shortsighted," countered Allen. "If we believed we would never use bombs there would be no point in proceeding with Putt-Putt at all. I'm sure that on some basis we will do limited, maybe peaceful, testing. We should proceed as if this were the case."[249]

"Our space-ship project is going through a rough time," Freeman reported on August 14. "We have still not had our budget approved for next year, and there is a possibility we may get the axe."[250] A compromise was reached that saved the project, but not by much. ARPA would support Orion at its current level, under the auspices of AFSWC, for another year, but during that time would transfer the project either to NASA or to the Air Force. Neither organization was enthusiastic about sponsoring the project on its own. "It was felt at command headquarters that the Air Force would not be unduly concerned if the project management passed from ARPA to NASA," notes the Air Force account compiled in 1964.[251] For the Air Force to advance Orion beyond a feasibility study, they would either have to come up with an unequivocal military requirement, enlist the cooperation of NASA, or both.

Twenty-ton

test vehicle: 21 feet in diameter; 35 feet in height, number of

charges, yield,

and date unknown.

In late August of 1959, ARPA granted another $1,000,000 to extend the original contract for a further twelve months. On September 23, 1959, Herbert York, now Eisenhower's Director of Defense Research and Engineering, a new top-level position with direct financial authority over some 80,000 individual projects, announced "a plan for the progressive and orderly transfer of space projects from the Advanced Research Projects Agency to the military departments."[252] In a telegram to de Hoffmann and Ted Taylor, Art Rolander (former counsel to the AEC, who had acted against Oppenheimer during his security hearings in 1954, and was now General Atomic s vice president and Washington office manager) added that "this means that the Air Force now has the responsibility for 'Space.' Will explain Orion implications upon my return."[253] Orion would go to the Air Force unless NASA could be persuaded to take the reins.

On January 29, 1960, York wrote to NASA headquarters seeking their assistance in disengaging Orion, in whole or in part, from the Department of Defense. The answer was no. "Although the ORION propulsion device embraces a very interesting theoretical concept, it appears to suffer from such major research and development problems that it would not successfully compete for support in the context of our entire space experimentation program," NASA responded, on February 10. "Among other uncertainties, the question of political approval for ever using such a device seems to weigh heavily in the balance against it. It would be extremely difficult to divert funds from nearer term projects for the support of ORION. We would not, therefore, favor any arrangement requiring such support."[254] NASA was out.

ARPA Project 4977, known as Orion, was transferred to the Air Force effective March 10, 1960, becoming Air Force Project 3775. The good news was that Orion now had a home, with AFSWC as a directing agency rather than just the contract monitor for an ARPA feasibility study that was already in its second year. The bad news was that Orion was now removed from the mainstream of the national space exploration effort, with decreasing chances, despite continued technical recommendations at high levels, of ever getting the political go-ahead. "Orion had to either be adopted as the principal means of getting to the moon or else it wouldn't fly," Freeman explains. "It was either us or Wernher von Braun's big rockets. Once the decision was made to go ahead with the Apollo system and Saturn 5, then it meant we were out." The decision to favor Apollo over Orion was made long before Kennedy made his public announcement, on May 25, 1961, that the United States was going to land men on the Moon by the end of 1969.

The Air Force faced an increasingly difficult struggle to justify a role for the military in deep space. "When ARPA decided to turn it over to the Air Force then it became, effectively, a military project," says Freeman. "Although the Air Force was reasonable about it. They understood that it was really a fraud and they were supporting it for reasons they couldn't openly acknowledge. By law, the Air Force was not supposed to support anything except for military requirements and I couldn't see any military requirements for this that made any sense. Once it belonged to the Air Force you could never do what I wanted it to do. As soon as it grew big it would attract political attention and then it would be resisted because no one really wanted the Air Force to have a big new weapons system like that. That was the point at which I gave up my hopes that it would really take us to Saturn. When I left at the end of that year, the project was still going strong. But I think politically it had already failed by that time."

Back in La Jolla, progress was being made against the major technical problems: ablation, shock absorbers, pusher-plate engineering, and pulse-unit design. Thanks to formal and informal collaboration between General Atomic physicists and their colleagues at the AEC's weapons laboratories, smaller and more directional nuclear explosives were in the works. Numerical models continued to evolve, and, when the test moratorium was lifted, these codes were verified by the explosion of actual bombs. "We should think of Orion as paving its own way through the nuclear explosion test ban, rather than simply waiting for it to disappear," suggested Ted.[255]

As bombs became smaller and their output better collimated, it became possible to contemplate smaller vehicles, so that even as expectations of full-scale funding diminished, hopes for a proof-of-principle test flight remained. "Confidence in the propulsion concept has risen so high that the initiation of a program leading to the construction and flight of a research vehicle is now warranted," AFSWC announced on April 1, 1960, proposing "a nuclear test vehicle capable of orbiting a 200-ton payload in the 1965-66 time period."[256] The financial plan, expected to be endorsed by the Scientific Advisory Board, called for $4,800,000 for fiscal year '61 and $55,000,000 for fiscal year '62 and envisioned "placing the Research Test Vehicle in orbit by fiscal year '65."[257] Mixson supplied the requisite military justification: "The successful completion of this project will satisfy some or all of the requirements of General Operational Requirement 173, An Advanced Strategic Space Weapon System; General Operational Requirement 156, Ballistic Missile Defense System; and such other GORs as pertain to the utilization of space systems for combat, reconnaissance, surveillance, communication, and navigation."[258]

"The Air Force, from the chief of staff on down, were all charged up and ready to go at the end of the first year," remembers Ted. In the fall of 1960, Ted's optimism rose further with the hope that a new administration in Washington might take a more active approach to space. "Marshall Rosenbluth reported that Kantrowitz, now on a committee advising Kennedy, reports the committee wants to establish a 1-A priority for Orion," Ted noted in his journal on November 7, 1960. "I fervently hope Kennedy wins tomorrow!"[259] Kennedy did win, and in January 1961, Jerome Wiesner, chairman of the incoming president's Ad Hoc Committee on Space, issued a report. "We must encourage entirely new ideas which might lead to real breakthroughs," he advised. "One such idea is the Orion proposal to utilize a large number of small nuclear bombs."[260] But by this time the foundations of the Apollo program were already in place. Mars and Saturn would have to wait.

The president-elect also commissioned a more detailed space policy study, reporting to General Bernard Schriever, commander of the Air Force Ballistic Missile Division, and organized by Air Force assistant secretary Trevor Gardner, who asked Ted to lead the group. The study, "which apparently has been specifically requested by Kennedy," was to occupy a full two months, Ted noted on November 15. "So, I'm caught between the devil and the deep blue sea—the worst time in the Orion project's history for me to be taking off for a couple of months on the one hand, and the possibly crucial importance of being in on the workings of this committee on the other."[261]

Ted accepted the assignment, and succeeded in guiding the uniformly distinguished but otherwise disparate members of the Gardner Committee to a consensus calling for the Air Force to move boldly into space. "Economical space travel on an enormous scale seems to me to be a certainty before the end of the century," he noted privately. "What we're doing now with chemical rockets seems quantitatively analogous to flying cargo across the country in a Boeing 707, and throwing away the airplane at the end of the trip! I expect to see the day when a round-trip to the moon will cost less than an airplane trip around the world costs now."[262]

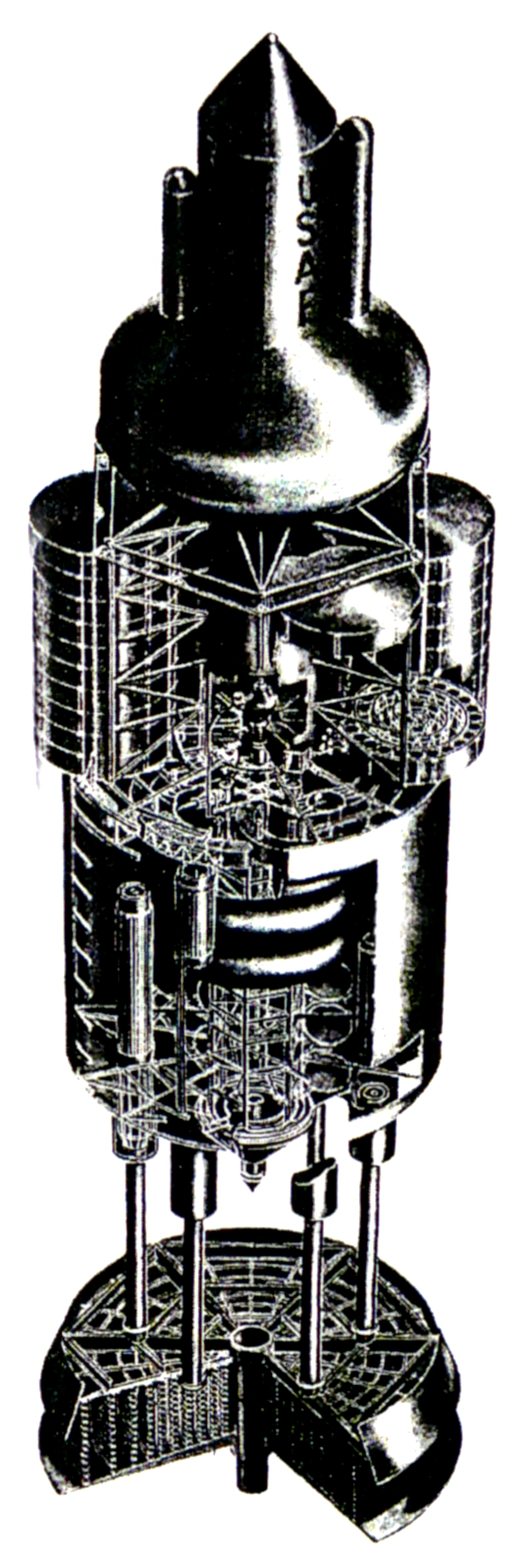

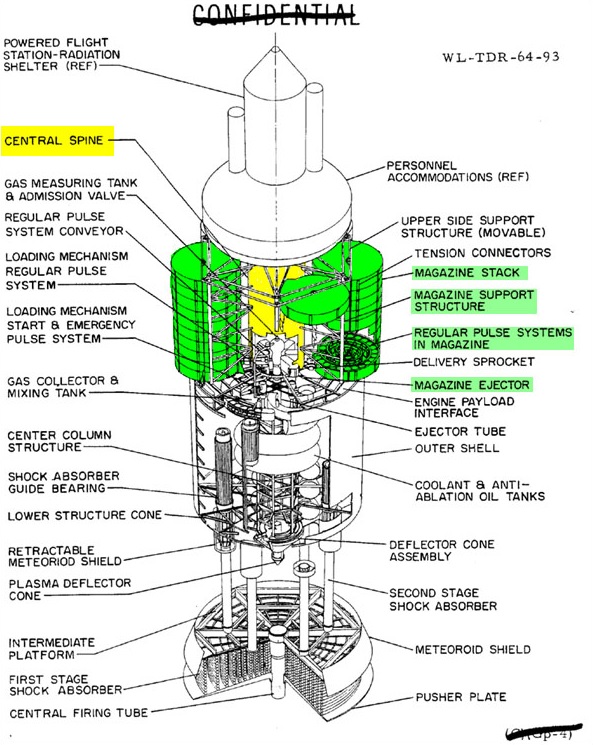

U.S.

Air Force military payload version of a

10-meter-diameter Orion vehicle: pulse units are stored in

individual helical magazines.

The meetings began in Los Alamos on December 4, in temporary quarters provided by Norris Bradbury in a facility that had been built to house the new IBM supercomputer, due to arrive in March. After a week of preliminary discussions Ted reported that the group had set three major goals: "1) Establishment of a manned orbited space laboratory, probably via orbital rendezvous & assembly, using chemical rockets; 2) Establishment of a permanent manned lunar base; 3) Carry out a manned expedition to the surface of Mars."[263] A week later he was able to add that "Bruno Augenstein, Keith Brueckner, and I came up with the notion of a manned round-trip to the moon's surface, using Atlas-Centaur, and rendezvousing both in orbit around the earth and in orbit around the moon. Concluded that three men could be landed and return to earth orbit in a 5,000 lb. final wt. vehicle, using ten Atlas Centaurs in all. Could this be done by the end of 1964??"[264]

After "much discussion of military vs. nonmilitary aspects of space," the group reached a "general conclusion that a dividing line really does not exist."[265] By the end of January, when the group was writing up its final report, Ted noted that "we are certainly all agreed now that the Air Force should go all out for man in space."[266] In conjunction with the Los Alamos working group, Cardner invited a supplemental advisory group (of "face cards," as he called them) to meet in Washington, where Ted presented a summary of the envisioned space program for review. "Charles Lindbergh was on that committee, he had all the clearances," remembers Ted. "I took an instant strong liking to him—the famous boyish grin is still there, though he is in his early fifties. He seemed intensely interested, particularly in the possibilities for manned space travel.[267] We talked about how Orion worked and how it was an important part of the space study committee findings that Orion should go, for half an hour or an hour in several walks around the Pentagon, mostly on the third floor." When the committee's final report was issued and presented in a series of briefings in Washington at the end of March, it was well received. "We've kicked a field goal," Trevor Gardner told Ted.[268]

"The consensus among the members of the committee was to go for this several-hundred-million-dollar proof test of Orion," Ted recalls. "That didn't change the course of anything, but it was a real high point, because it looked as though the project was going to go. We had this prestigious Air Force committee recommending building Orion and opening up the whole solar system. We would manage it from San Diego and at that time the plan was to take off from Jackass Flats. The assembly would be down there with the construction by a variety of contractors. That was the peak of my expectations of actually participating."

A list of 105 individuals, with security clearances, who attended a Project Orion briefing at the Air Force Ballistic Missile Division in Los Angeles reveals the contractors who were standing by. There were four representatives from Boeing, five from Convair, six from Firestone, four from Hughes, four from McDonnell, three from Lockheed, three from Martin, five from Northrop, twelve from North American Aviation, and six from Norair.[269] Things would have been hopping at Jackass Flats. "We were trying to shift the scale of effort and build things, in particular what we called the twenty-ton flying model, an actual model of the whole thing, and fly that up through the atmosphere, with very small nuclear explosions, after ground testing with high explosive," explains Ted. "The idea was that we could mock up the mechanical effects by detonating sheet high explosive of the right type and density and thickness to get any kind of a pulse that we wanted, with the shock-absorber system upside down on the ground.

"We had designs with maybe a hundred explosions, basically a scaled-up version of the Putt-Putt. We'd then use shaped high explosive charges, so the pulses would be stretched out. We would know that it could take the initial shocks, but then would it take the momentum transfer? All the way to the top, repeatedly, and would it fly? The delivery systems for the explosives and so on, of that twenty-ton model, became a sharp focus, the next thing we'd do. We were planning to do that the next year, but that got to be pretty big money, probably ten million dollars a year."

"The whole time between 1960 and 1964, this thing was coming along well," remembers Don Prickett. "The theoretical work was paying off and you got to the point where you had a little test program that sort of gets you interested. But the scale-up, the money it took to go beyond that, was an order of magnitude more. We could have done some more engineering and theoretical work at a slower pace. But we all felt it was time to make a step forward in the engineering end, and that was to go to bigger models. That's a lot more money, and you need another test base somewhere. Jackass Flats gave us security and avoided the press."

Jackass Flats, designated Area 25 of the Nevada Test Site, lies seventy-five miles northwest of Las Vegas, over the Funeral Mountains and across the Amargosa Desert from Death Valley, between Yucca Mountain and Yucca Flat. "They did a lot of strange things in Nevada," says Bud Pyatt. Some of the strangest things were done at Jackass Flats. It was the site for a series of open-core reactors (named Kiwi, after the flightless bird) that were tested for application to nuclear-powered rockets, with one million gallons of liquid hydrogen propellant stored on site. Larger Orion tests would probably have had to move to the South Pacific, but Jackass Flats, only 300 miles from La Jolla, was the perfect place to start things off. "I get very excited right now just thinking about that thing being out there and flying it," says Ted. "Not because it was nuclear, but because we would then want to go nuclear in flight-testing the real thing, that is, the 4,000-ton vehicle scaled down to a couple of hundred tons."

By late 1961 bomb design had improved to where the propellant could be collimated within a cone of 22.5 degrees, allowing a standoff distance of 75 feet for a 200-ton ship with a pusher plate diameter of 30 feet. Some 800 pulse units weighing 220 pounds each would deliver a 44 ft/sec kick every 3/4 of a second, for an acceleration of about 2 g.[270] This test vehicle would have been unmanned, so Dave Weiss would still have had to wait for a chance at a first flight. He did, however, plot Orion's course. In addition to engineering studies such as ORION Charge-Propellant Fire Control, he produced a series of mission studies such as Maneuvering Technique for Changing the Plane of Circular Orbits with Minimum Fuel Expenditure; Computation Techniques for Fast Transit Earth-Mars Trips; A General Discussion of Earth-Mars Interplanetary Round-Trips; Arrested Rendezvous, a New Concept; and Comments on Use of Lunar or Planetary Material for ORION Propellant. "NASA was very jealous about the idea of these round-trips to Mars," he says.

Weiss also did the pre-design and weapons configuration on a large scale model of Orion, constructed at the request of SAC, that was presented by General Thomas Power to President Kennedy at Vandenberg Air Force Base in early 1962. This model—"Corvette sized," according to Weiss—was built by a subcontractor in San Diego at a cost of $75,000 and appeared only briefly at General Atomic before being packed up for shipment to Vandenberg late one Friday night. "We suddenly got word that the government wanted this thing up in Vandenberg," remembers Ted. Some remember the model as "bristling with bombs," others that it was equipped with 5-inch guns. The cutaway exposed the command centers and quarters for the crew—"Big enough so that at least one person, I think maybe a couple, were inside the model when Kennedy was there," says Ted. "It was an interesting model," says Weiss. "We had warheads of various caliber. I pretty well standardized on something around twenty-five megatons; we had a bunch of them, enough to make it suicidal for anybody to even contemplate going after either the Orion or simply doing a first strike on the United States. We also had Casabas shown on the model—something Kennedy had never heard of.

"We designed a reentry vehicle to go along with the thing, and these are the vehicles that we had in the scale model," Weiss explains, referring to a number of auxiliary space-shuttle-like landing craft. "And Kennedy was impressed with them; they'd hold about as many people as he'd ever put on a PT boat." Here at least was something on a scale that Kennedy could relate to; by most accounts the scale of Battleship Orion left him questioning the sanity of the project and certainly did not win his support. "We were looking at the scale model—and this was when Kennedy was there—just simply discussing how powerful it could be," remembers Weiss. "And I said, 'Well, it would take out every Russian city over the population of 200,000 if we wanted to build the next larger model. We'd have enough weapons to do that.' " According to Ted, "Kennedy was shown a model of Orion that had 500 Minuteman-style warheads on it, and the means for propelling them out with directional explosives. He was absolutely appalled that that was going on, had no use for it. So not everybody greeted the project with enthusiasm. They did when it was presented as a way of exploring space and mostly were very disapproving when it was presented as a space battleship or anything like that."

The model disappeared from sight. Doug Fouquet, who had served as General Curtis LeMay's public information officer at the Strategic Air Command from 1953 to 1955 before becoming public relations director at General Atomic, says that "it had a lot of compartments, it was like the Enterprise on Star Trek." He remembers it being flown up to SAC headquarters "in the hold of a C-97 and that de Hoffmann requested him to accompany it but he turned the assignment down. Weiss, who last saw it "up in Vannieland" thinks "it's probably sealed up in a box in one of these salt mines that they keep stuff in. God only knows where, it could even be at SAC " He remembers that in 1967, just before he left General Atomic, "some people came and talked to some of the Orion people; they talked to me, and they knew about the model. And I asked one of them, 'Do you know where it is?' He answered, 'If I knew, I couldn't even tell you.' "

The delivery of that model to SAC headquarters may have been Orion's final flight. "Although I'd love the first flight bonus, the whole thing was a moot point," Weiss now admits about the dreams of forty years ago to be aboard Orion when it launched. "Unlike an airplane, the Orion vehicle would have the glide ratio of a rock and must either reach orbit or be 'splashed' or 'smashed' as safely as possible. Unless a pilot could uniquely operate or save the vehicle better than any on-board triple-redundant flight management system, he has no business being aboard. The worst experimental accidents seem to often be accompanied by having more than the minimum human crew complement aboard. The time to introduce observers and/or flight crew is after Orion is in orbit and after the space worthiness of the vehicle has been determined and deemed adequate for its next mission by inspection and repair. Needless to say, many in the military do not agree with an unmanned launch; and particularly that the first people to board it in orbit should be engineers!"