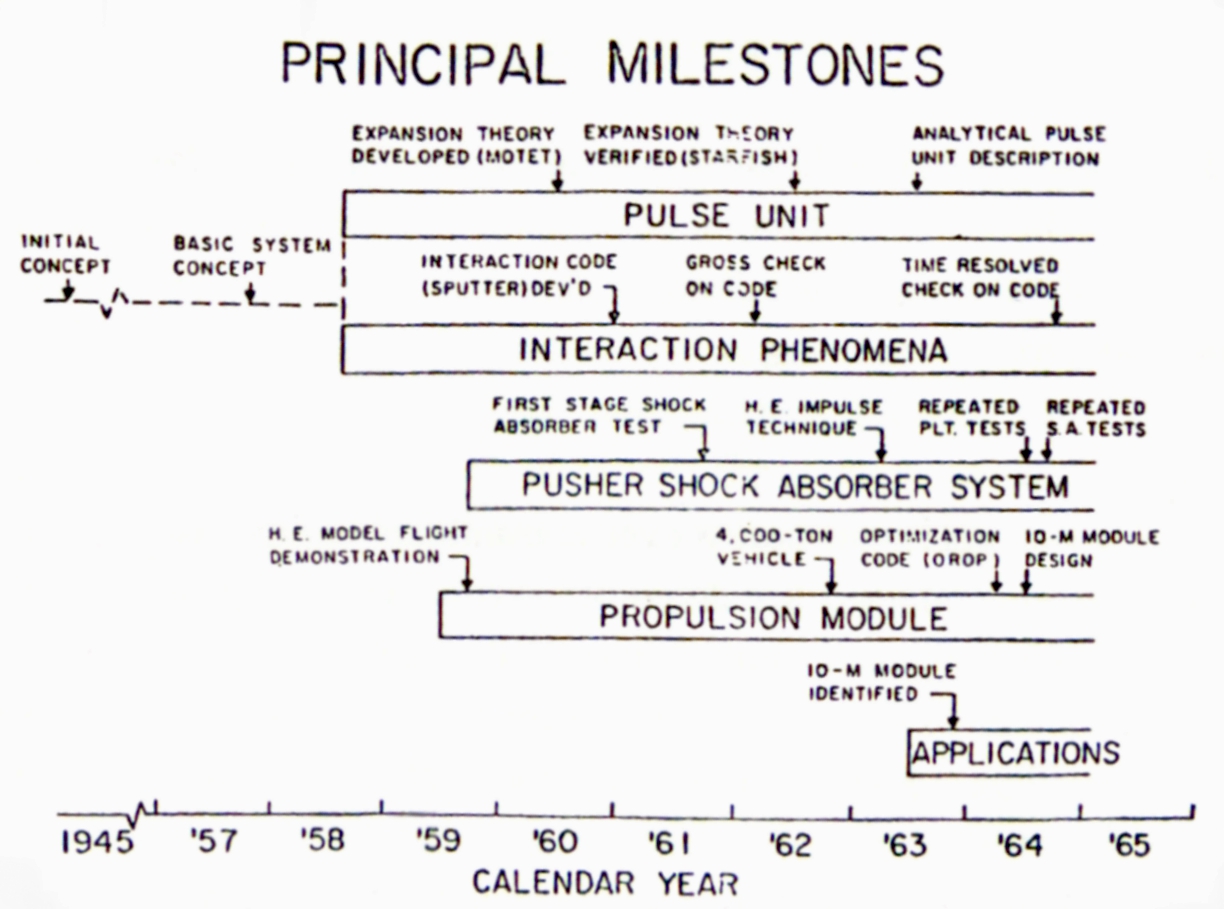

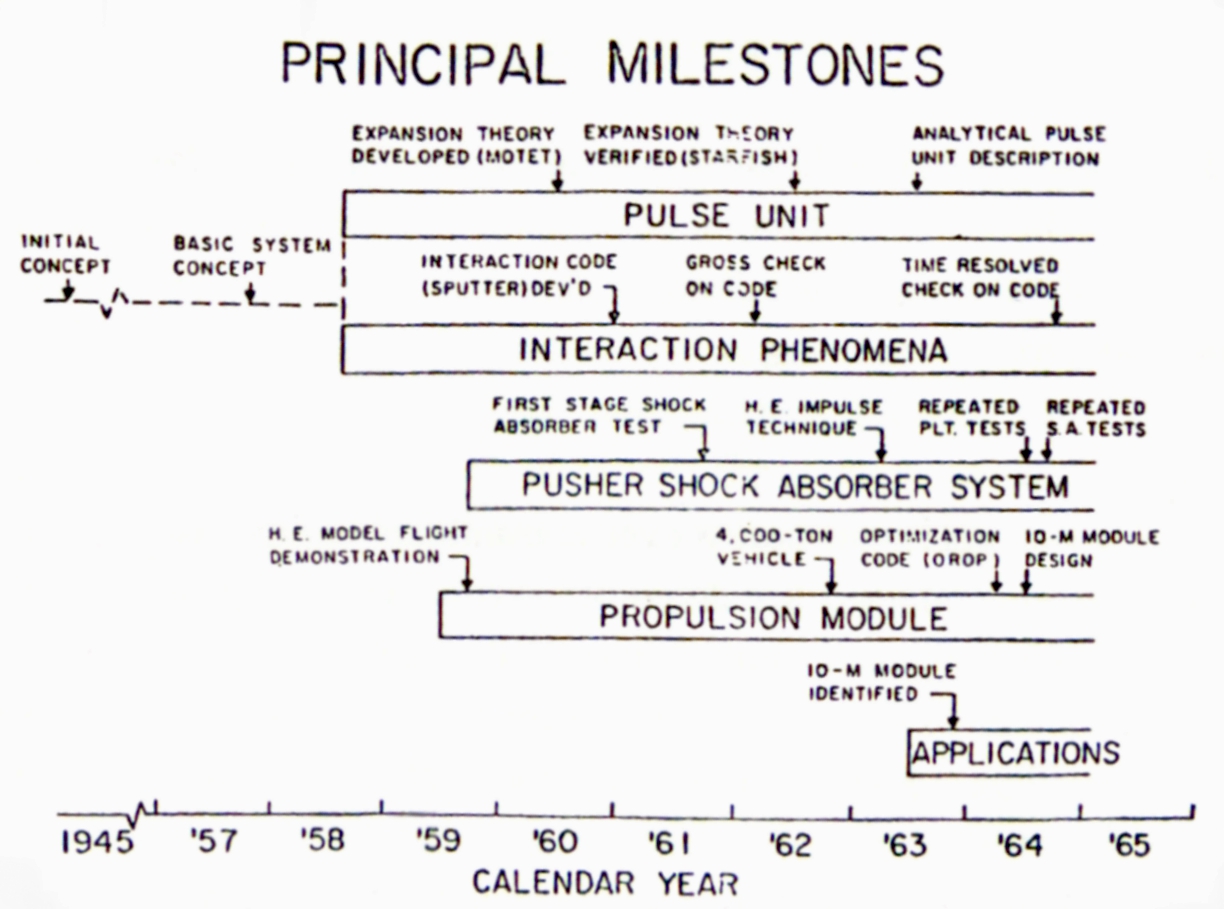

Project Orion milestones, 1957-1965, along five related theoretical and experimental design/development tracks.

NASA's support for Orion was short-lived. Huntsville remained enthusiastic, and Wernher von Braun even issued a white paper, Nuclear Pulse Propulsion System—Its Potential Value to NASA, which, although eventually leaked to the Air Force, was "withheld from general circulation for several months."[325] But without support from Washington, Huntsville could do little else. "NASA headquarters is fighting any further support with a vigor which I think is way out of proportion to the low level of support which Huntsville is proposing," Ted reported to Freeman at the end of 1963. "Many people in NASA like to string everything out in a line, which makes it unthinkable to them that serious work should be started on ORION until after a nuclear rocket is carrying useful payloads around. Some officials even suggest that a good time for ORION might be about 1990!"[326]

Ted regarded Project Orion's struggles as an example of Fermi's Law: "If you don't fail a good part of the time you're not doing your job." Orion succeeded in advancing science, but failed to advance against politics, because it pushed too many limits at once. "Orion had a unique ability to antagonize simultaneously the four most powerful sections of the Washington establishment," Freeman explained upon the death of the project in March of 1965. "The remarkable thing is that, against such odds, with its future never assured for more than a few months at a time, the project survived as long as it did."[327] Freeman held four groups of people responsible: the Defense Department, the heads of NASA, the promoters of the test-ban treaty, and the scientific community as a whole. Two other groups—the AFC and the general public—stood by at the execution, one of them unwilling and the other unable to help.

The Department of Defense—excepting the physicists at AFSWC, the adventurers at ARPA, and the Deep Space Warriors at SAC—viewed Orion either as subverting bombs and dollars for nonmilitary purposes, or as the ultimate in expensive weapons systems removed from fighting real wars on the ground. NASA—excepting a minority at Huntsville—viewed Orion as a reckless leap beyond Apollo, an unaffordable competitor to Rover, and an unacceptable public relations risk because of the bombs. The test-ban establishment—excepting Hans Bethe—either ignored Orion completely or viewed it as a dangerous extension of the arms race, the promise of peaceful explosions in space a loophole best left closed. The scientific establishment had no reason to defend a project that was too deeply classified to openly advance science in space. The AEC, absent from Freeman's list of critics, supported Orion initially but then grew increasingly ambivalent about a bomb-driven project that did not belong to one of its own labs.

The public learned little about Orion until the project was at an end. "For reasons which I always find elusive, the Defense Department is very touchy about dissemination of Orion information to the public," pondered Ted in 1963. "I frankly think that this is because they are afraid of an upsurge of public support."[328] Lew Allen remembers a flight from California to Washington, when "Ted got up and explained to the entire body of the airplane what this idea was, and asked would they think it was worth the money for them to have a dollar of their taxes a year go to funding this project, to see if they could really make it work to go to the planets. And needless to say, he got an overwhelming vote for it from the entire airplane.

The amount of money spent on Orion—$10.4 million over seven years[329], supplemented by about $1 million contributed by General Atomic during periods when outside funds were scarce—was trivial in proportion to the debate over its cost. The government's contributions were as follows (not including AFSWC's staff and logistical support): AEC—$5,000; ARPA—$2,325,000; AF/DOD—$8,070,000; NASA—$100,000. Even the much larger sums requested in hopes of advancing to nuclear tests and working models were modest by the standards of NASA, the AEC, or the Department of Defense. "When you look at some of the early budgets that were proposed for Orion, it's almost absurd," says Bruno Augenstein. "A few tens of millions of dollars? When you think of what was being spent on other programs at the time, many of which were not successful, it is fascinating."

At its peak, the project employed fifty people at General Atomic and was spending $150,000 a month. Throughout seven years of work, nothing turned up that conflicted fundamentally with the optimism of 1958. "The end result was a rather firm technical basis for believing that vehicles of this type could be developed, tested, and flown," Freeman claims. "The technical findings of the project have not been seriously challenged by anybody. Its major troubles have been, from the beginning, political. The level of scientific and engineering talent devoted to it was, for a classified project, unusually high."[330] The endless succession of obstacles discouraged the scientists in La Jolla and frustrated the project officers in Albuquerque, who were impatient to move ahead. "Orion, in its current status within the DOD, is plagued primarily with non-technical or pseudo-technical problems (no military mission, large development costs, need for nuclear tests, difficult to flight test, etc., etc., ad infinitum)," complained Ron Prater, who had taken over after Don Mixson had been transferred to the Strategic Air Command. "The real technical problems are currently relatively well in hand."[331]

Upon President Kennedy's inauguration in January of 1961 there was a changing of the guard at the Pentagon, with Robert S. McNamara becoming secretary of defense. Much had changed since 1958. The initial shock over Sputnik had subsided and the clandestine arms and surveillance race, being fought with unmanned missiles and satellites, had been eclipsed by the public spectacle of manned space flight, which now belonged to NASA, not the Department of Defense. Orion was a relic of the Air Force's once-grand designs. "McNamara was against these Air Force extravaganzas," explains Freeman. "He wanted the military to concentrate on doing down-to-earth things, fighting real wars rather than playing around with technical toys. He was always an enemy of the Air Force and a friend of the Army, more or less."

Project

Orion milestones, 1957-1965, along five

related theoretical and experimental design/development tracks.

When Orion was transferred from ARPA to the Air Force, the contract, administered by the Research Directorate of the Physics Division at AFSWC, officially fell under the Ballistic Missile Division of the Air Research and Development Command. In April 1961 the Air Force was reorganized, with Orion going to the Space Systems Division of the newly created Air Force Systems Command. Orion was neither a satellite nor a missile, and whenever its budget rose above $2 million, the threshold requiring Department of Defense approval, it stood out like a sore thumb. AFSWC did its best to shelter Orion from its critics, but the project found itself in trouble every time it tried to grow. Whenever Orion officials asked for an amount like $30 million, the response was either that this was too much for a feasibility study, or too little for the development of anything in space. "Every time you push a number into the next column, it gets attention," says Ed Ciller. "We had to either get on or get off the pot," adds Don Prickett, "and what they said was get off the pot."

In May of 1961, Harold Brown, formerly director of Livermore, succeeded Herbert York as director of Defense Research and Engineering, or DDR&E, where the real decisions about Pentagon spending on programs like Orion were being made. "In the early '60s, the military departments ran in a very different way than they are running today," explains Augenstein, who served under Harold Brown. "In those days, DDR&E had a very complete authority over the military programs. We could insert programs into the Air Force budget and remove programs from the Air Force budget. It doesn't have that authority today. So the Air Force was in a real sense under Brown's thumb in those days. Harold was not, as I recall, a supporter of Orion. He kept asking, 'What's it going to be used for? And who needs it?' "

On August 30, 1961, the Soviets announced a resumption of nuclear testing, and on September 1, 1961, they ended the thirty-four-month moratorium with a 150-kiloton atmospheric test. Additional tests followed on September 4 and 5, prompting Kennedy (whose first reaction was "unprintable") to announce that the United States would resume testing as well. There was an intense, behind-the-scenes debate over whether to set off as many bombs as quickly as possible, demonstrating that the United States had not been caught off guard, or exercise restraint. This was Orion's chance.

By the end of September Orion's project officers were ready with plans for a series of seven nuclear tests, using 20-foot-diameter pusher plates and low-yield, spherical-assembly bombs. Three tests would be performed in vacuum tanks and four would be lofted by rocket to an altitude of 200,000 feet. These plans generated considerable interest within the AEC and Department of Defense, including preliminary approval from Harold Brown, but no agreement over who would supply the funds. By November of 1961 Orion officials at AFSWC and General Atomic had revised their proposals and were seeking $15 million in emergency funding to conduct five tests that would be lifted by balloons and two that would be exploded in underground tanks. Permission to use White Sands Missile Range for the balloon shots had been obtained, distinguishing the Orion experiments from the ongoing Nevada weapons tests.

The amount of money was reasonable and the experiments well thought out. The AEC was discovering that underground tunnels were expensive to dig, difficult to instrument, and prone to "containment" problems. Orion offered a plausible justification for testing at high altitude or in space, and the tests could help answer questions about X-ray ablation and high-altitude electromagnetic effects that were critical to warhead survival and missile defense. The Soviets had exploded fifty more bombs by the second week of November, and the hawks at SAC were pointing to Soviet duplicity about test preparations during the moratorium as justifying deployment of Orion as a show of force. Livermore and Los Alamos were prepared to supply the sub-kiloton devices, to be designated as propulsion tests, not weapons tests, keeping the door open should NASA change its mind. Everything was set to go.

Harold Brown, however, decided it was time to get Orion's nose out of the Defense Department tent. "On 28 December 1961, the Department of Defense disapproved emergency funds for Project ORION, relinquished its support of the project, and authorized the expenditure of up to $98,000 over a period of 60 days to terminate it," AFSWC's historians reported.[332] On January 1, 1962, Space Systems Division advised the Special Weapons Center to proceed accordingly unless otherwise instructed within forty-eight hours. With no further word from the Pentagon, AFSWC had no choice but to start closing things down. The deciding factor was probably not the emergency funding requested for the 1962 test series but the $33,250,000 budget that had already been submitted to the Department of Defense for fiscal year 1963. Hundreds of millions of dollars (including what DDR&E referred to as "astronomical" plutonium costs) might be next.

"Orion was an answer to a completely unstated question, and I think that had a lot to do with its lukewarm reception," says Augenstein. "The McNamara regime was very heavily focused on the notion of finding a justifiable role for these things. A lot of interesting capabilities went by the wayside. Harold Brown had a very strict rule that if there wasn't some stated military justification for a program, he wasn't going to fund it. Orion certainly came within that rubric as far as he was concerned."

"The Orion program, on paper, worked better and better the bigger it got," Augenstein continues. "And that was a novel thought to a lot of people. When something had to be four thousand tons to be superior to any contemporary system, that didn't lead to a lot of jubilation, because you knew you had to take a lot of steps to get there, and those steps are going to be expensive. Orion was a victim of external circumstances that had little to do with the pros and cons of the program itself. There were a lot of powerful forces in Washington at that time: NASA with its manned program, the DOD and USAF with their circumscribed and covert programs, which they didn't want to jeopardize in any sense. There was a manned Apollo program in NASA and the DOD space program was tied up in this very covert National Reconnaissance Office, NRO. The fact that Orion was a manned program, in the Air Force, played a counterproductive role with NASA in the end."

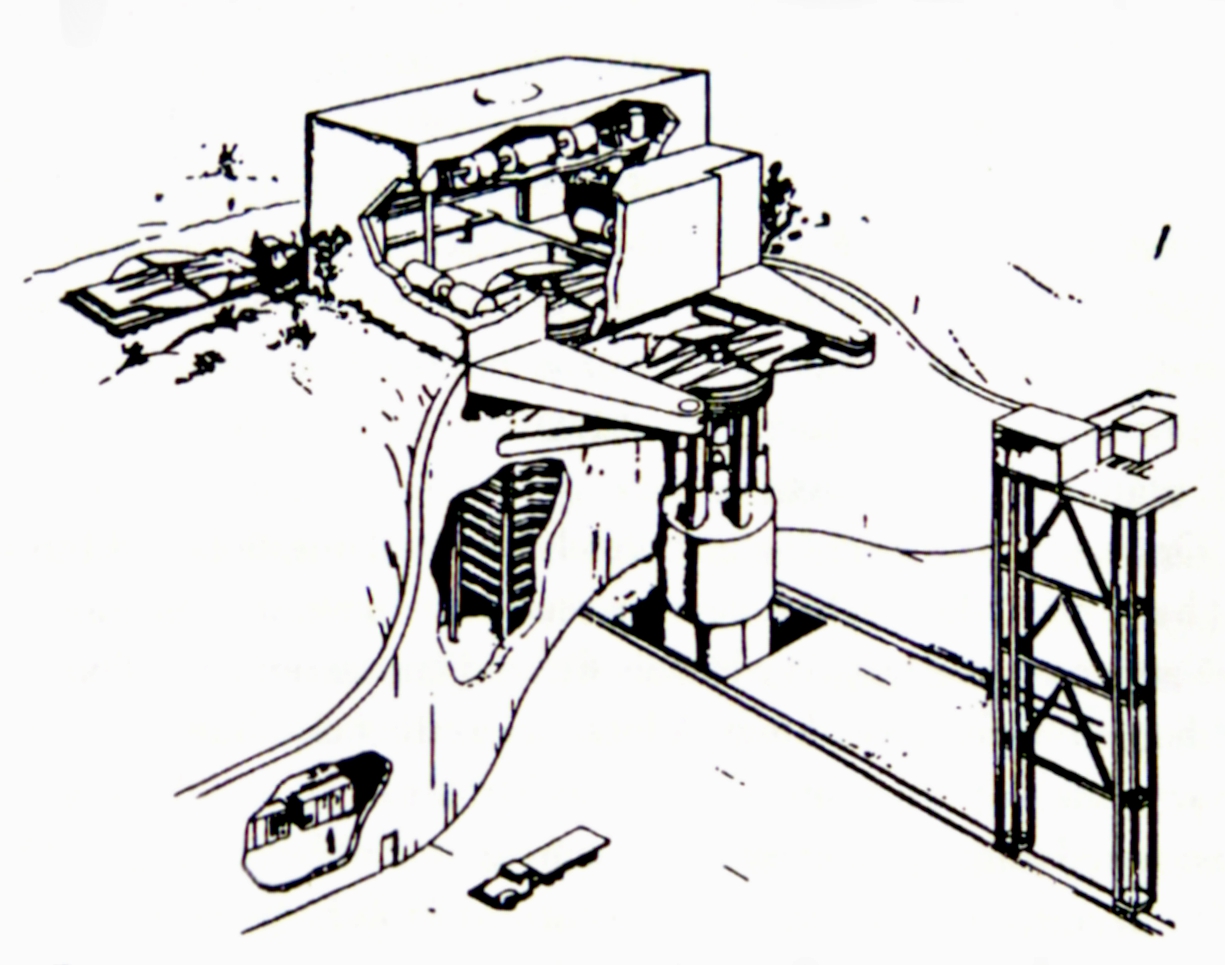

Repetitive high-explosive test facility designed by Hans Amtmann and Ed Day in 1964 to allow pulse-per-second testing of a full-size 10-meter Orion engine on the ground.

Orion was rescued, at the beginning of 1962, by its allies in Washington, aided by the realization that the work at General Atomic had implications for certain immediate problems of nuclear defense. "Clearly the feasibility of Orion has not been established," Hans Bethe cabled to Joseph Charyk, undersecretary of the Air Force, on January 18, 1962. "However, the project seems far more feasible today than it did when work was started. With a concept as radical as this, the development usually goes the other way, namely that the problem looks more difficult after three years of work than at the beginning. It seems to me that the funds requested, some $2 million, are sufficiently small that a way should be found to make them available and to continue the work of this excellent group."[333] The Air Force agreed. "We have taken steps to reprogram funds to keep the technical group at General Atomics active," Charyk answered. "Work will be primarily oriented toward the fundamental problems of ablation and the energy-focusing mechanism. Both of these areas, we believe, may contain fundamental payoffs, not only in the propulsion area but in relation to their possible application in focused energy weapons, nuclear effect on re-entry vehicles, and discrimination in the area of decoys and penetration aids."[334] This last point was critical: when faced with a cluster of incoming objects, how do you distinguish the warheads from the decoys? With radar you cannot tell the difference between a bomb and a balloon, but by flooding incoming targets with a bomb-driven pulse of directed radiation it becomes possible to distinguish—or even incapacitate—them at a distance that remains as deeply classified in 2001 as in 1961.

By August of 1962 Orion had received an additional $1,795,000 from the Air Force and was lobbying for further support. Orion officials appeared before the Congressional Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, and a five-year technology development plan contained renewed proposals for nuclear tests. General Power at SAC, not to be outdone, endorsed a ten-year program that would spend $4.5 billion on building a deep-space fleet by 1973. General Atomic started making arrangements with the AEC to perform the initial tests. But in late September AFSWC received word that Harold Brown had decided against the test program "on the grounds that there was no military mission for man in space."[335] On November 2, McNamara officially disapproved the proposed Orion tests.

Orion was being squeezed to death between two opposing extremes: too little interest from NASA and too much interest from the Strategic Air Command. "Those big briefings by SAC with a hundred slides of variations, themes, and more variations on the theme 'whoever develops Orion will rule the world' had a very negative effect on a lot of people," says Ted, "and I think that had a lot to do with it being easy to kill." Ted remembers the 8-foot-high model of an Orion battleship being displayed in a classified area of the Pentagon either shortly before or after being presented to President Kennedy at Vandenberg Air Force Base in early 1962. "Many who saw it in Washington were appalled," he says. "Making that model was a serious mistake."[336] The Department of Defense was willing to sustain Orion as a theoretical study, but without a firm military requirement or the commitment of NASA to a civilian mission they were not going to let it off the ground.

Thomas Power's Qualitative Operational Requirement (QOR) of January 1961, calling for a Strategic Earth Orbital Base "capable of sustaining extremely heavy, composite payloads from low orbits to lunar distances and beyond," whose "integrated facilities and systems for effective mission accomplishment must include all functions that permit survival, surveillance, and weapons delivery... unrestricted by propulsion or payload limitations," was not the kind of requirement that DDR&E had in mind.[337] "Men as wise and critical as Harold Brown and McNamara could easily see that the military applications of Orion are either spurious or positively undesirable," Freeman observed.[338] Every few months the project came up for review by one advisory panel or another, and the recommendations were generally the same: the science was sound but its application was undefined.

"There is certainly a chance that a clear-cut need will emerge for a propulsion system with a high specific impulse and large thrust," concluded the Air Force Scientific Advisory Board in 1964. "If that should happen, it would be desirable to have at least one approach sufficiently far advanced in research and development, so that the U.S. could proceed quickly and confidently toward that goal. ORION is one of the very few concepts that hold promise for this purpose. For these reasons the majority of the Panel members feel that the decision should be made to pursue ORION through its next logical step. If a need for ORION should eventuate, the Panel believes that the need is as likely to be in the peaceful exploration of space as in the military use of space. For this reason, the Panel feels that, in the future, sponsorship (funding) of ORION should come jointly from NASA and the Air Force. The Panel recommends that the Air Force try to bring about this change."[339]

A series of meetings were held January 13-16, 1964, in Huntsville, attended by officials from NASA, AFSWC, and General Atomic. NASA officials were told that "Fiscal Year 1965 signified the end of the line' for ORION under exploratory development." The Air Force would be proposing an advanced development program for Orion in fiscal year 1966, but, to gain approval from the secretary of defense, "the Space Administration would have to express strong support." The result was the "full support of Dr. von Braun contrary to persistent opposition from Mr. Finger."[340] Huntsville's conclusion, based on the past six months of mission studies, that Orion would outperform Rover/NERVA had little effect either on NASA Deputy Administrator Hugh Dryden, NASA Director James Webb, or the joint AEC-NASA Space Nuclear Propulsion Office (SNPO). NASA's Office of Manned Space Flight (OMSF), led by George E. Mueller, architect of the Apollo program, sided with Huntsville and von Braun. "The in-house battle was bitter and hard-fought between OMSF and Nuclear Rocket interests (and NASA management)," says Nance. "OMSF had convinced themselves that on practically every mission criterion of importance, Orion scored significantly better than any propulsion system under consideration. Mueller and von Braun went down swinging. Dryden and Finger emerged the champions."[341]

The Air Force, giving up on NASA, began preparing to shut things down. "In accordance with guidance from HQ, USAF the proposed effort has been designed to bring the research program to a logical stopping point at the end of FY 64," AFSWC officials explained in requesting a final $2,820,000 to bring Project Orion to a close. "The end result of this procurement will be a complete series of mothball' reports summarizing in detailed handbook form the results of all previous research in nuclear impulse propulsion. Such handbooks will preserve the essential data from this project in a systematic form and will allow the project research to be discontinued and restarted later, if so desired, with a minimum loss of continuity."[342]

Ted and the AFSWC gang kept lobbying the Pentagon, while Nance kept lobbying NASA. "The Air Force and General Atomic were able to pick up strong support within DOD," inside sources reported. "However, the Defense Department still felt it could not afford to continue supporting this effort without, in effect, putting the military in space. But it did give its blessings to a proposed joint effort with NASA and the AEC.[343]

General Atomic and AFSWC proposed a two-year continuation of proof-of-principle research, including three underground nuclear tests, for a total cost of $12 million split between fiscal years 1966 and 1967. DOD was asked to put up $8 million and the AEC $4 million. DOD responded that it would be willing to supply half of the requested $8 million, provided NASA would supply the other half. The AEC refused to advance any funding, but confirmed that if DOD and NASA agreed to cooperate on Orion, AEC would contribute the bombs. "Los Alamos was willing to talk," says test director William Ogle of their response toward Orion, "but in general took the attitude bring money and then we will play.' "[344] Orion's fate was in NASA's hands. "The result of the DOD and AEC positions has been to hang the fate of the program on NASA as the only agency that could justify a mission requirement for a nuclear pulse vehicle," Missile/Space Daily reported. "A Pentagon source said, 'If NASA says no, it's out.' "[345]

By this time there was strong support for Orion not only from NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville but also from NASA's Ames Research Center in California, where a parallel study of Orion had issued a favorable report. The showdown came on July 17, 1964, at the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory in Livermore, California, when briefings on Orion were presented to NASA officials by Air Force, Los Alamos, and General Atomic personnel. Before the meetings, Hugh Dryden circulated a memo outlining NASA's "official position"[346] that "in view of the shortage of NASA funds for both Fiscal Years 1964 and 1965, we are having to curtail a number of important projects which we believe offer much earlier possibilities of utilization than would Project ORION. Therefore, we do not expect to undertake any follow-on effort on that project in either of these two fiscal years."[347]

"The purpose of the meeting was to acquaint the NASA representatives with the current status of Orion and proposed future plans and to solicit their interest and support," the Air Force explained. "Based on the comments of NASA representatives, it is apparent that the latter portion of the meeting objective was not achieved. No further action expressing interest or support by NASA of the Orion concept is anticipated."[348] The Air Force then went back to General Atomic for their "rock bottom" cost to maintain a "minimum but meaningful" effort. General Atomic answered $500,000 to $1 million, without nuclear tests. According to Aviation Week, "The Air Force then approached NASA—this time unofficially—with a compromise proposal: each would put up $500,000 to keep Orion going through fiscal year 1966. Again NASA refused."[349] One NASA official told Missiles and Rockets that Orion "probably is the only concept we have now that might permit manned missions to planets other than Mars" and another inside source commented that "you wouldn't expect this kind of furor to be raised over a piddling amount like that unless some people are afraid nuclear pulse will work."[350]

Hope was running out. "Unless Jim Webb's or Harold Brown's mind can be changed during the next couple of months," Ted reported in early July, "ORION is likely to disappear as a government project as of January 1 of next year."[351] Ted, now chairman of General Atomics nascent Department of High Energy Fluid Dynamics—"because we reached a point where more money was coming in on nuclear weapons effects than on Orion"—decided to take a break. At the end of the summer, he took his family, including four children and a dog, up to the headwaters of the San Joaquin River near Huntington Lake in the Sierra Nevada, where they hiked to a remote campsite and settled in. After a couple of days in camp, remembers Ted, "we were sitting there cooking breakfast and here comes a young man with torn pants and his suit coat draped over his arm, carrying a big manila envelope, and in the manila envelope was an invitation to go out and see Harold Brown and General Donnelly at the Pentagon about a job." The messenger was Dan Baker, assistant to Art Rolander, General Atomics chief counsel in Washington. "He had a terrible struggle getting up there," says Ted. "He ran into a rattlesnake, which he thought threatened him, but he delivered his envelope, we gave him some pancakes, and he went back down the path to the road."

The job was a new position as Deputy Director (Scientific) at the Defense Atomic Support Agency (DASA), the division of the Pentagon responsible for everything nuclear, from maintaining the stockpile to weapons testing to theoretical work on weapons effects. "I was being told, in effect, 'If you don't like the way it's working, come and fix it,' " says Ted.[352] With the encouragement of General Atomic, he accepted the job, relinquished his stock options, uprooted his family, and moved to Washington. "It was a new job where a civilian was given in-line authority over all the R&D and weapons effects, so that I had the rank of a two-star general in the bowels of the Pentagon." Ted came up with one last plan to save Orion—the plan that Niels Bohr had suggested five years earlier at the Hotel Del Charro.

Besides the opposition from NASA and DDR&E, Orion now faced the Limited Test Ban Treaty of 1963, precluding flight-testing Orion with real bombs. "The treaty, however, provides procedures for its own amendment," wrote Paul Shipps in March 1965, "and the spirit of the treaty is clearly not to prevent the development of advanced space propulsion nor to hinder the scientific exploration of space."[353] If the Air Force could not justify launching Orion against the Russians, why not launch Orion with the Russians? "Those of us working on the project believed that it should be carried through those test phases that were not prohibited by the treaty, because we were convinced that the practicality of the concept could be so tested in detail," Ted explained. "If the tests were successful, we argued, then the United States would have a sound basis for proposing what most of us had hoped for all along: a truly international effort to explore space on a big scale."[354]

Ted remembers giving "an impassioned plea for going after Orion on the grounds that Apollo, which was quite far along by 1965, was a dead end. If it looked practical after another three years of hard work, we would follow through with the Russians on a round-trip to Mars, with the Saturn 5 booster taking the Orion engine up in two or three pieces, rendezvousing in orbit and then getting out far enough so there would be no hazard of radioactive material being dumped on the earth. The ship would be on its way to Mars, at escape velocity, before it went nuclear." The joint U.S.-U.S.S.R. Orion mission that Niels Bohr—who died in November 1962—and others believed in might have had a chance, if the issue of weapons testing and deployment in space could have been resolved. Andrei Sakharov, in his memoirs, describes "A Meeting of Party and Government Leaders with the Atomic Scientists" convened by Khrushchev on July 10, 1961. "I went on to describe some of my department's more exotic projects," says Sakharov, "such as the use of nuclear explosions to power spacecraft and other 'science fiction' schemes."[355] Ted later became friends, in Vienna, with a Soviet nuclear physicist, Vladimir Shmelev, of the Kurchatov Institute, who admitted to having monitored what the Orion group was up to, but as far as Ted knows the Soviet weapons community never developed any equivalent project in response.

In early 1965, there were three developments in Orion's favor. Nance succeeded in getting the basic operating capabilities of the smaller Saturn-boosted Orion vehicles declassified, allowing limited discussion of the idea in public and in the open literature, minus technical details. Ted secured a commitment from DASA to support at least one underground nuclear test. There was growing determination in NASA to look at manned missions beyond the Moon, and official recognition that available vehicles were ill-suited to the job. "There appears to be a growing feeling within NASA that 400-500 day Mars missions are too long," explained Missile/Space Daily in a report on renewed interest in Orion, "both from the standpoint of reliability and a space crew's mental health."[356]

Ted found an ally in Lieutenant Colonel John R. Burke, of the Air Force's Nuclear Power Division, who came from the nuclear-powered aircraft project and had been a consultant, at AEC headquarters, to Harry Finger on radiation effects. Burke, who later went to work for NASA, understood Finger's reasons for opposing Orion—"You can't blame him, he had his career and his position in NASA based on the NERVA engine"—but sided with Ted because "Orion had so much more capability than NERVA, and in reality they were both in about the same stage of development."

"ORION is not 'just another' advanced propulsion system," Burke argued in January 1965. "Practically every DOD/Air Force and NASA evaluation over the past 3 years has concluded that ORION provides the only capability for missions well beyond those achievable with chemical or nuclear rocket propulsion. The results point to a technique of rapidly traversing interplanetary distances substantially superior to any other method known today. Although the Department of Defense supports the concept as being technically sound, without NASA support the DOD and Air Force will not continue the program. All work on ORION technology is therefore scheduled to cease in April 1965."[357]

Orion's future depended on conducting a nuclear test to find out whether the ablation predictions were sound. Ted Taylor and Moe Scharff designed an asymmetric, low-yield nuclear device—called Low Energy Nuclear Source, or LENS—which would fire a jet of high-velocity plasma at a sample pusher plate: a nuclear version of the high-explosive implosion tubes developed by Brian Dunne. Directing the energy equivalent of about a hundred tons of high explosive at an 8-foot-diameter pusher plate 20 feet away, it would finally give some indication whether ablation was survivable or not.

"Even Harold Brown was ready to sign off," Ted wrote to Freeman.[358] The proposal was so clearly within the sphere of DASA's immediate responsibility, and within the bounds of the test-ban treaty, that everyone could get on board. "There was a moment in time, about six weeks, in which NASA, the AEC, and the key people following Orion agreed to fund a program in which all testing was done underground, not trying to fly a model or anything like that, a single test of our capacity to predict the effect of this material as it hit the pusher," remembers Ted. "General Atomic made a proposal for a three-year practicality demonstration program, and if that were successful so that things looked at least as good for Orion as they did at the start, then we'd go to the Russians and say let's do it together. And then NASA fell out of bed."

According to Nance, who spoke with NASA deputy administrator Earl Hilbum, the reasons for the negative decision, despite "no technical or mission objections," were that NASA had "no requirement for manned planetary missions," and that "if a big expansion is wanted it must be a political decision of Congress, not an internal NASA question."[359] The decision, by all accounts, was close. "There were a lot of people down at Huntsville that were very much in favor of Orion," says Burke, "and there were a few people at headquarters, but like everybody else their hands were tied, and that was the end of it. Harry was a smart, capable individual and knew his way around NASA and the rest of it. So he prevailed, and we lost."

In February 1965, the Orion staff at General Atomic was down to nine and "formal research on this project was brought to a close."[360] The only remaining effort was to close out the project's records and produce a final report. On June 30, 1965, Major John O. Berga of the Air Force Weapons laboratory issued a terse, one-page Plan Change: "Objective. To establish the inherent feasibility of Nuclear Impulse Propulsion and to maintain currency in the technologies of other nuclear propulsion concepts. Results: None. This Project is hereby terminated."[361] Orion was at an end.

Freeman completed his obituary on March 1, published four months later in Science under the title "Death of a Project: Research is stopped on a system of space propulsion which broke all the rules of the political game." He summarized where the project succeeded and why it failed. "I understand that there is now no chance at all of saving ORION as a project," he explained to Stan Ulam. "My concern is to make sure that the public knows what has happened, so that they will be ready to come back to these ideas when the time is ripe."[362]

He sent a copy to Robert Oppenheimer, describing it as "a partial answer to the question 'What does Christopher Robin do in the mornings?' "—a reference to the early days of the project, when his absences from the Institute in Princeton were as mysterious as Christopher Robin's absences from the 100-acre wood. "You will perhaps recognize the mixture of technical wisdom and political innocence with which we came to San Diego in 1958, as similar to the Los Alamos of 1943. You had to learn political wisdom by success, and we by failure. Often I do not know whether to be glad or sorry that we escaped the responsibilities of succeeding."[363]

"The men who began the project in 1958," Freeman wrote, "aimed to create a propulsion system commensurate with the real size of the task of exploring the solar system, at a cost which would be politically acceptable, and they believe they have demonstrated the way to do it."[364] But, after the initial euphoria came to an end, "there was no more brave talk of manned expeditions to Mars by 1965, and of sampling the rings of Saturn by 1970. What would have happened to us if the government had given full support to us in 1959, as it did to a similar bunch of amateurs in Los Alamos in 1943? Would we have achieved by now a cheap and rapid transportation system extending all over the Solar System? Or are we lucky to have our dreams intact?"[365]