George Washington's 1796 musings about a United States so powerful that none could "make us afraid" reflected the fear that gripped the nation throughout the turbulent 1790s, a time of dire threats from without and bitter divisions within. They also put into words the first president's vision of an American empire invulnerable to such dangers. If the United States could avoid war for a generation, he reasoned, the growth in population and resources combined with its favorable geographic location would enable it "in a just cause, to bid defiance to any power on earth."1 Washington and his successor, John Adams, set important precedents in the management of foreign and national security policy. Conciliatory at the brink of war, they managed to avert hostilities with and wring important concessions from both England and France. They consolidated control of the western territories awarded in the 1783 peace treaty with Britain, laying a firm foundation for what Washington called the "future Grandeur of this rising Empire."2 The Federalists' conduct of U.S. foreign policy significantly shaped the new nation's institutions and political culture. Through skillful diplomacy and great good fortune, the United States emerged from a tumultuous decade much stronger than at the start.

During the first years under its new Constitution, the United States faced challenges in foreign relations unsurpassed in gravity until the mid-twentieth century. In 1792, Europe erupted in a war that for more than two decades would convulse much of the world in bitter ideological and military struggle. Americans agreed as a first principle of foreign policy that they must stay out of such wars, but neutrality afforded little shelter. Europe "intruded" on America "in every way," historian Lawrence Kaplan has written, "inspiring fear of reconquest by the mother country, offering opportunity along sparsely settled borderlands, arousing uncertainties over the alliance with a great power."3 The new nation depended on trade with Europe. The major belligerents attempted to use the United States as an instrument of their grand strategies and respected its neutrality only when expedient. The war also set loose profound divisions within the United States, and the internal strife in turn threatened America's ability to remain impartial toward the belligerents. Nor did the United States, while claiming neutrality, seek to insulate itself from the conflict. Rather, like small nations through history, it sought to exploit great-power rivalries to its own advantage. Sometimes brash and self-righteous in its demeanor toward the outside world, assertive in claiming its rights and aggressive in pursuing its goals, the nation throughout the 1790s was constantly embroiled in conflict. At times its very survival seemed at stake.

The United States in 1789 remained weak and vulnerable. When Washington assumed office, he presided over fewer than four million people, most of them concentrated along the Atlantic seaboard. The United States claimed vast territory in the West, and settlement had expanded rapidly in the Confederation period, but Spain still blocked access to the Mississippi River. The isolated frontier communities had only loose ties to the federal union. British and Spanish agents intrigued to detach them from the United States while encouraging the Indians to resist American expansion. Economically, the United States remained in a quasi-colonial status, a producer of raw materials dependent on European credits, markets, and manufactured goods. Washington and some of his top advisers believed that military power was essential to uphold the authority of the new government, maintain domestic order, and support the nation's diplomacy. But their efforts to create a military establishment were hampered by finances and an anti-militarist tradition deeply rooted in the colonial era. On the eve of war in Europe, the United States had no navy. Its regular army totaled fewer than five hundred men.

The Constitution at least partially corrected the structural weaknesses that had hampered the Confederation's conduct of foreign policy. It conferred on the central government authority to regulate commerce and conduct relations with other nations. Although powers were somewhat ambiguously divided between the executive and legislative branches, Washington sure-handedly established the principle of presidential direction of foreign policy.

The first president created a Department of State to handle the day-to-day management of foreign relations, as well as domestic matters not under the War and Treasury departments. His fellow Virginian Thomas Jefferson assumed the office of secretary, assisted by a staff of four with an annual budget of $8,000 (including his salary). The other cabinet officers, particularly the secretaries of war and treasury, inevitably ventured into foreign policy. Washington made it a practice to submit important questions to his entire cabinet, resolving the issue himself where major divisions occurred. In keeping with ideals of republican simplicity—and to save money—the administration did not appoint anyone to the rank of ambassador. That "may be the custom of the old world," Jefferson informed the emperor of Morocco, "but it is not ours."4 The "foreign service" consisted of a minister to France, chargés d'affaires in England, Spain, and Portugal, and an agent at Amsterdam. In 1790, the United States opened its first consulate in Bordeaux, a major source of arms, ammunition, and wine during the Revolution. That same year, it appointed twelve consuls and also named six foreigners as vice-consuls since there were not enough qualified Americans to fill the posts.5

A keen awareness of the nation's present weakness in no way clouded visions of its future greatness. The new government formulated ambitious objectives and pursued them doggedly. Conscious of the unusual fertility of the land and productivity of the people and viewing commerce as the natural basis for national wealth and power, American leaders worked vigorously to break down barriers that kept the new nation out of foreign markets. They moved quickly to gain control of the trans-Appalachian West, encouraging emigration and employing diplomatic pressure and military force to eliminate Native Americans and foreigners who stood in the way. Even in its infancy, the United States looked beyond existing boundaries, casting covetous eyes upon Spanish Florida and Louisiana (and even British Canada). Perceiving that in time a restless population that was doubling in size every twenty-two years would give it an advantage over foreign challengers, the Washington administration accepted the need for patience. But it prepared for the future by encouraging settlement of contested territory. Rationalizing their covetousness with the doctrine that superior institutions and ideology entitled them to whatever land they could use, Americans began to think in terms of an empire stretching from Atlantic to Pacific long before the population of existing boundaries was completed.6

The most urgent problem facing the new government was the threat of Indian war in the West. The "condition of the Indians to the United States is perhaps unlike that of any other two people in existence," Chief Justice John Marshall would later write, and clashing interests as well as incompatible concepts of sovereignty provoked conflict between them.7 Most of the tribes scattered through the trans-Appalachian West lived in communal settlements but roamed widely across the land as hunters. American frontier society, on the other hand, was anchored in agriculture, private property, and land ownership, and Americans conveniently rationalized that the Indians had sacrificed claim to the land by not using it properly. The Indians only grudgingly conceded U.S. sovereignty. Increasingly aware that they could not hold back American settlers, they sought to contain them in specified areas by banding together in loose confederations, signing treaties with the United States, seeking assistance from Britain or Spain, or attacking exposed frontier settlements. Following precedents set by the colonial governments, the United States had implicitly granted the Indians a measure of sovereignty and accorded them the status of independent nations through negotiations replete with elaborate ceremony and the signing of treaties. As a way of asserting federal authority for Indian affairs over the states, the Washington administration would do likewise. From its birth, however, the United States had vehemently—and contradictorily—insisted that the Indians were under its sovereignty and that Indian affairs were therefore internal matters. The various land ordinances enacted by the Confederation presumed U.S. sovereignty in the West and sought to provide for orderly and peaceful settlement. But the onrush of settlers and their steady encroachment on Indian lands provoked retaliatory attacks and preemptive strikes.

The Washington administration desperately sought to avoid war. With limited funds in the treasury and no army, the infant government was painfully aware that it could not afford and might not win such a war. At this time, Americans in the more settled, seacoast areas accepted the Enlightenment view that all mankind was of one species and capable of improvement. In addition, Washington and Secretary of War Henry Knox insisted that the United States, a bold experiment in republicanism closely watched by the whole world, must be true to its principles in dealing with the Indians. For the short term, the administration sought to avert war by diplomacy, building on the treaties negotiated under the Confederation to keep Indians and settlers apart and achieve cheap and peaceful expansion. For the long term, Knox promoted a policy of expansion with honor that would make available to the Indians the blessings of American civilization in return for their lands, a form of pacification through deculturation and assimilation.8

Washington's diplomacy achieved short-term results in the Southwest. The powerful Creeks had traditionally preserved their independence by playing European nations against each other. Eager to bind the autonomous groups that composed the tribe into a tighter union under his leadership and to fend off onrushing American settlers, the redoubtable half-breed Alexander McGillivray journeyed to New York in 1790 and amidst pomp and ceremony, including an audience with the Great Father himself (Washington), agreed to a treaty. In return for three million acres of land, the United States recognized the independence of the Creeks, promised to protect them from the incursions of its citizens, and agreed to boundaries. A seemingly innocent provision afforded a potentially powerful instrument for expansion with honor. "That the Creek nation may be led to a greater degree of civilization, and to become herdsmen and cultivators, instead of remaining in a state of hunters," the treaty solemnly affirmed, "the United States will from time to time furnish gratuitously the said nation with useful domestic animals and implements of husbandry."9 The United States also provided an annuity of $1,500. The bestowing of such gifts would help civilize the Indians and, in Knox's words, have the "salutary effect of attaching them to the interests of the United States."10 A secret protocol gave McGillivray control of trade and made him an agent of the United States with the rank of brigadier general and an annuity of $1,200.

In the short run, each party viewed the treaty as a success. It boosted the prestige of the new U.S. government, lured the Creeks from Spain, and averted conflict with the most powerful southwestern tribe. It appeared to the Creeks to recognize their sovereignty and protect them from American settlers, buying McGillivray time to develop tribal unity and strength. In fact, the state of Georgia did not respect the treaty and the United States would not or could not force it to do so. Boundaries were not drawn, and settlers continued to encroach on Creek lands. To entice McGillivray away from the United States, Spanish agents doubled the pension provided by Washington. The Creek leader died in 1793, his dream of union unrealized, conditions in the Southwest still unsettled.11

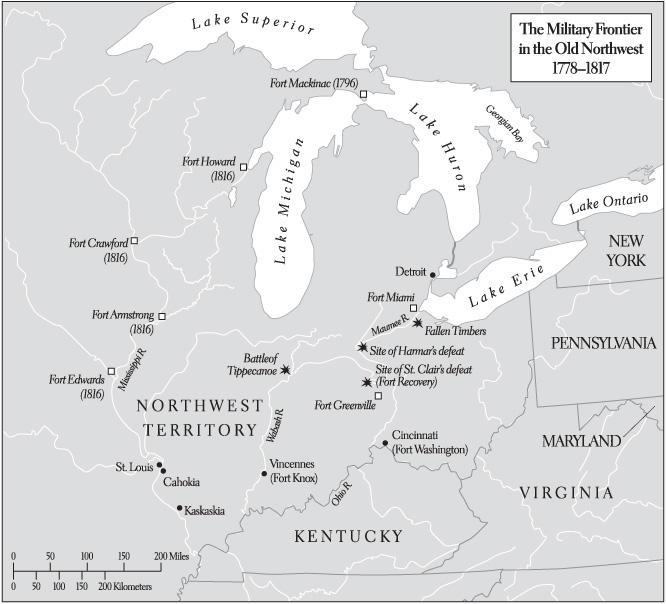

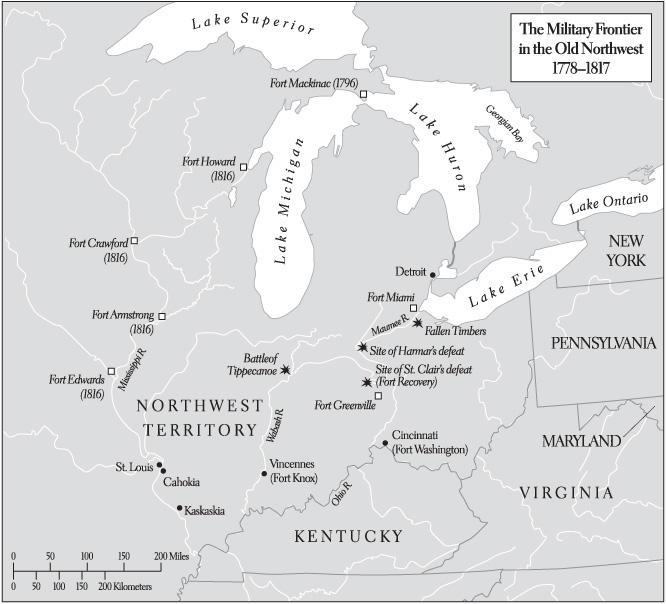

The Northwest was far more explosive. The Confederation government had signed treaties with Indians north of the Ohio River, but some tribes had refused to go along, and those who had were dissatisfied. With British encouragement, the Indians sought to create a buffer state in the Northwest. As settlers poured into the area, tensions increased. Frontier people generally viewed the Indians as inferior savages and expendable and preferred to eliminate rather than pacify them. Eventually, their view prevailed.

Eager to avoid war and uphold American honor, the Washington administration capitulated to pressure from land speculators and settlers in Kentucky and elsewhere along the frontier. The administration continued to negotiate with the Indians, but it approached them in a highhanded manner that made success unlikely: "This is the last offer that can be made," Knox warned the northwestern tribes. "If you do not embrace it now, your doom must be sealed forever."12 By backing its diplomacy with force, moreover, the administration blundered into the war it hoped to avoid. In 1790, to "strike terror into the minds of the Indians," Washington and Knox sent fifteen hundred men under Josiah Harmar deep into present-day Ohio and Indiana. Returning to its base after plundering Indian villages near the Maumee River, Harmar's force was ambushed and suffered heavy losses. To recoup its prestige among its own citizens and the Indians with whom it sought to negotiate, the administration escalated the conflict in 1791, sending fourteen hundred men under Gen.

Arthur St. Clair into Indian country north of Cincinnati. St. Clair's small and ill-prepared force was annihilated, losing nine hundred men in what has been called the worst defeat ever suffered by an American army.13 On the eve of war in Europe, the United States' position in the Northwest was more precarious than before, its prestige shattered.

The terrifying reality of slave revolt in the Caribbean and specter of slave rebellion at home further heightened American insecurity in the early 1790s. Inspired by the rhetoric of the French Revolution, slaves in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (the western third of the island of Hispaniola, present-day Haiti) rebelled against their masters in August 1791. At the height of the struggle, as many as one hundred thousand blacks faced forty thousand whites and mulattoes. The fury stirred by racial antagonism and the legacy of slavery produced a peculiarly savage conflict. Marching into battle playing African music and flying banners with the slogan DEATH TO ALL WHITES, the rebels burned plantations and massacred planter families.14

Americans' enthusiasm for revolution stopped well short of violent slave revolt, of course, and they viewed events in the West Indies with foreboding. Trade with Saint-Domingue was important, the exports of $3 million in 1790 more than twice those to metropolitan France. Friendship with France also encouraged sympathy for the planters. Some Americans worried that Britain might exploit the conflict on Saint-Domingue to enlarge its presence in the region. But the U.S. response to the revolution derived mainly from racial fears. At this time, attitudes toward slavery remained somewhat flexible, but those who favored emancipation saw it taking place gradually and peacefully. The shock of violent revolt on nearby islands provoked fears of a descent into "chaos and negroism" and the certainty, as Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton put it, of "calamitous" results. Southerners like Jefferson harbored morbid dread that revolt would extend to the United States, setting off a frenzy of violence that could only end in the "extermination of one or the other race." State legislatures voted funds to help the planters on Saint-Domingue suppress the rebellion. Stretching executive authority, the Washington administration advanced France $726 million in debt payments and sold arms to the planters.15

Such efforts were unavailing. The rebel victory in June 1793 sent shock waves to the North. Defeated French planters fled to the United States, bringing tales of massacre that spread panic throughout the South. While Jefferson privately fretted about the "bloody scenes" Americans would "wade through" in the future, southern states tightened slave codes and began to develop a positive defense of the "peculiar institution."16 Nervousness on the northwestern frontier was exceeded by the horror of slave revolt in the South.

Republican ideology looked upon political parties as disruptive, even evil, but partisan politics intruded into foreign policy early in Washington's first term, a development that the president himself never fully accepted and that, throughout the 1790s, significantly influenced and vastly complicated the new government's dealings with the outside world. The struggle centered around the dynamic personalities of Jefferson and Hamilton, but it reflected much deeper divisions within U.S. society. It assumed a level of special intensity because the participants shared with equal fervor the conviction of revolutionaries that each step they took might determine the destiny of the new nation.17 In addition, in a new nation any domestic or foreign policy decision could establish a lasting precedent.18

Tall, loose-jointed, somewhat awkward in manner and appearance, Jefferson was the embodiment of the southern landed gentry, an aristocrat by birth, an intellectual by temperament, a scholarly and retiring individual who hated open conflict but could be a fierce infighter. Small of stature, born out of wedlock in the West Indies, Hamilton struggled to obtain the social status Jefferson acquired by birth. Handsome and charming, a man of prodigious intellect and boundless energy, he was driven by insatiable ambitions and a compulsion to dominate. Jefferson represented the predominantly agricultural interests of the South and West. Optimistic by nature, a child of the Enlightenment, he had faith in popular government—at least the elitist form practiced in Virginia—viewed agriculture and commerce as the proper bases for national wealth, and was almost morbidly suspicious of the northeastern moneyed groups who prospered through speculation. To Hamilton, order was more important than liberty. A brilliant financier, he believed that political power should reside with those who had the largest stake in society. He attached himself to the financial elite Jefferson so distrusted. The dispute became deeply personal. Hamilton viewed Jefferson as devious and scheming. Jefferson was offended by Hamilton's arrogance and transparent ambition. He especially resented that the secretary of the treasury seemed to have Washington's ear.19

The Hamilton-Jefferson foreign policy struggle has often been portrayed in terms of a realist/idealist dichotomy, with Hamilton cast as the realist, more European than American in his thinking, coldly rational and keenly sensitive to the national interest and the limits of power, Jefferson as the archetypical American idealist, intent on spreading the nation's principles even at costs it could not afford. Such a construct, although useful, imposes a modern frame of reference on eighteenth-century ideas and practices and does not do justice to the complexity of the diplomacy of the two men or the conflict between them.20

Both shared the long-range goal of a strong nation, independent of the great powers of Europe, but they approached it from quite different perspectives, advocating coherent systems of political economy in which foreign and domestic policies were inextricably linked with sharply conflicting visions of what America should be. Hamilton was the more patient. He preferred to build national power and then "dictate the terms of the connection between the old world and the new."21 Modeling his system on that of England, he sought to establish a strong government and stable economy that would attract investment capital and promote manufactures. Through expansion of the home market he hoped in time to get around Britain's commercial restrictions and even challenge its supremacy, but for the moment he would acquiesce. His economic program hinged on revenues from trade with England, and he opposed anything that threatened it. Horrified at the excesses of the French Revolution, he condemned Jefferson's "womanish attachment" to France and increasingly saw England as a bastion of stable governing principles. More accurate than Jefferson and Madison in his assessment of American weakness and therefore more willing to make concessions to Britain, he pursued peace with a zeal that compromised American pride and honor and engaged in machinations that could have undermined American interests. His lust for power could be both reckless and destructive.

Deeply committed to perfecting the republican triumph of the Revolution, Jefferson and his compatriot James Madison, the intellectual force behind republicanism and leader in the House of Representatives, envisioned a youthful, vigorous, predominantly agricultural society composed of virtuous yeoman farmers. Their vision required the opening of foreign markets to absorb the produce of American farms and westward expansion to ensure the availability of sufficient land to sustain a burgeoning population. Britain stood as the major barrier to their dreams—it had "bound us in manacles, and very nearly defeated the object of our independence," Madison declaimed. Still, they were confident that a youthful, dynamic America could prevail over an England they saw as hopelessly corrupt and fundamentally rotten. Confirmed Anglophobes, they were certain from the experience with non-importation in the Revolutionary era that dependence on American necessities would force Britain to bend to economic pressure. They hoped to divert U.S. commerce to France. Although committed to free trade in theory, they proposed harsh discriminatory duties to force Britain to sign a commercial treaty.22

Jefferson and Madison were indeed idealists who dreamed of a world of like-minded republics. They were also internationalists with an abiding faith in progress who accepted, for the moment at least, the existing balance-of-power system and hoped to make it more peaceful and orderly through the negotiation of treaties promoting free trade and international law.23 Jefferson especially admired France and things French. He welcomed the French Revolution and urged closer ties with the new government. As a French diplomat pointed out, however, his liking for France stemmed in part from his detestation for England, and, in any event, Americans in general were "the sworn enemy of all the European peoples."24 He was also a tough-minded diplomatist, who advocated playing the European powers against each other to extract concessions. Jefferson and Madison saw Hamilton's policies as abject surrender to England. They viewed the secretary of the treasury and his cronies as tools "of British interests seeking to restore monarchy to America," an "enormous invisible conspiracy against the national welfare."25 In diplomacy, Jefferson was more independent than Hamilton and could be shrewdly manipulative, but his commitment to principle and his tendency to overestimate American power at times clouded his vision and limited his effectiveness.

The battle was joined when the new government took office. Conflict first broke out over Hamilton's bold initiative to centralize federal power and create a moneyed interest by funding the national debt and assuming state debts, but it quickly extended to foreign affairs. In 1789, an Anglo-Spanish dispute over British fur-trading settlements at Nootka Sound on Vancouver Island in the Pacific Northwest threatened war. Jefferson urged U.S. support for the side that offered the most in return. Hamilton did not openly dissent. Certain that American interests would best be served by siding with Great Britain, however, he confided in British secret agent George Beckwith (the secretary of the treasury was referred to as No. 7 in coded dispatches) that Jefferson's position did not represent U.S. policy. The differences became irrelevant when the threat of war receded, but they widened over commercial policy. Jefferson and Madison pushed for discriminatory duties against British commerce. Hamilton openly used his influence to block their passage in the Senate.26

Because of the sharp divisions within its own councils and primarily because of its continued weakness, the new government was little more successful than its predecessor in resolving the nation's major diplomatic problems. Britain in 1792 finally opened formal diplomatic relations, but Jefferson could not secure a commercial agreement or force implementation of the treaty of 1783. The United States was a relatively minor concern to Britain at this point. Content with the status quo, London did not take seriously Jefferson's threats of discrimination, in part because British officials correctly surmised that economic warfare would hurt America more than their own country, in part because of Hamilton's private assurances. In any event, Jefferson's bombastic rhetoric and uncompromising negotiating position left little room for compromise. The secretary of state fared no better with France and Spain. The French government refused even to negotiate a new commercial treaty and imposed discriminatory duties on tobacco and other American imports. Ignoring Jefferson's slightly veiled threats of war, Spain refused commercial concessions and would not discuss the disputed southern boundary and access to the Mississippi. On the eve of war in Europe, the position of the United States seemed anything but promising.

The outbreak of war in 1792 offered enticing opportunities to attain longstanding goals but posed new and ominous dangers to the independence and even survival of the republic. The Wars of the French Revolution and Napoleon differed dramatically from the chessboard engagements of the age of limited war. The French Revolution injected ideology and nationalism into traditional European power struggles, making the conflict more intense and all-consuming. Declaring war on Austria in August 1792, France launched a crusade to preserve revolutionary principles at home and extend them across the European continent. Alarmed by developments in Europe, England in February 1793 joined the Continental allies to block the spread of French power and the contaminating influence of French radicalism. Monarchical wars gave way to wars of nations; limited war to total war. The belligerents mobilized their entire populations not simply to defeat but to destroy their enemies, creating mass armies that fought with a new patriotic zeal. The conflict spread across the globe. Britain, as always, sought to strangle its adversary by controlling the seas. As with earlier imperial conflicts, colonies formed an integral part of the grand strategies of the belligerents. The war expanded to the Mediterranean, South Asia, and the Western Hemisphere.27

These wars of new ferocity and scope left the United States little margin for safety. The great powers of Europe viewed the new nation as little more than a pawn—albeit a potentially useful one—in their struggle for survival. Perceiving the United States as weak and unreliable, neither wanted it as an ally. Each preferred a benevolent neutrality that offered access to naval stores and foodstuffs, shipping as needed, and the use of U.S. ports and territory as bases for commerce raiding and attacks on enemy colonies. They sought to deny their enemy what they wanted for themselves. They were openly contemptuous of America's wish to retain commercial ties with both sides and insulate itself against the war. They blatantly interfered in U.S. politics and employed bribery, intimidation, and the threat of force to achieve their aims.

Americans had long agreed they must abstain from Europe's wars, and the new nation's still fragile position in 1793 underscored the urgency of neutrality. Individuals as different as Hamilton and Jefferson could readily agree, moreover, that to become too closely attached to either power could result in a loss of freedom of action, even independence. Sensitive to the balance-of-power system and their role in it, Americans also quickly perceived that, as in the Revolution, they might exploit European conflict to their own advantage. They also recognized that war would significantly increase demands for their products and might open ports previously closed. As a neutral the United States could trade with all nations, Jefferson observed with more than a touch of self-righteousness, and the "new world will fatten on the follies of the old."28

To proclaim neutrality was one thing, to implement it quite another. The United States was tied by treaty to France and by Hamilton's economic system to Britain, posing major threats to neutrality. Establishing a workable policy was also difficult because as a newly independent nation the United States lacked a body of precedent for dealing with the complex issues that arose. International law in the eighteenth century generally upheld the right of neutrals to trade with belligerents in non-contraband supplies and the sanctity of their territory from belligerent use for military purposes. It was codified only in bilateral treaties, however, which were routinely ignored in times of crisis. Within the general agreement on principles, there was considerable divergence in application. Following the practice of the small, seafaring nations of northern Europe, the United States interpreted neutral rights as broadly as possible. By contrast, Britain relied on sea power as its chief military instrument and interpreted such rights restrictively. Lacking a merchant marine and dependent on neutral carriers, the French accepted America's principles when it was useful, but when the United States veered in the direction of Britain, they reacted strongly. In the absence of courts to enforce international law and especially in the context of total war, power was the final arbiter. From 1793 to 1812, the United States could not maintain a neutrality acceptable to both sides. Whatever it did or refrained from doing, it provoked reprisals from one belligerent or the other.

Growing internal divisions also complicated implementation of a neutrality policy. Still sympathetic to France and seeing in the war an opportunity to free his country from commercial bondage to Britain, Jefferson persuaded himself that the United States could have both neutrality and the alliance with France. Increasingly alarmed by the radicalism of the French Revolution and more than ever persuaded that America's security and his own economic system demanded friendship with Britain, Hamilton leaned in the other direction, grandly indifferent to the consequences for France.29

The conflict surfaced when England and France went to war in 1793. In April, Washington requested his cabinet's advice on the issuance of a declaration of neutrality and the more prickly question of U.S. obligations under the 1778 alliance. Hoping to extract concessions from England, Jefferson urged delaying a statement of neutrality. Hamilton favored an immediate and unequivocal declaration, ostensibly to make America's position clear, in fact to avoid any grounds for conflict with London. The French alliance bound the signatories to guarantee each other's possessions in the Western Hemisphere and to admit privateers and prizes to their ports while denying such rights to their enemies. Acceptance of these obligations meant compromising U.S. neutrality; rejection risked antagonizing France. Hamilton advocated what amounted to unilateral abrogation of the alliance, arguing that the change in government in France rendered it void. Jefferson upheld the sanctity of treaties, claiming that they were negotiated by nations, not governments, and could not be scrapped at whim, but he was motivated as much by a desire to avoid offense to France as by respect for principle. He contended on a practical level that France would not ask the United States to fulfill its obligations, a prediction far off the mark. Washington eventually sided with Hamilton on the issuance of a declaration of neutrality and with Jefferson on the status of the French alliance, a compromise that satisfied neither of the antagonists but established the basis for a reasonably impartial neutrality.30

France and its newly appointed minister to the United States, Edmond Charles Genet, challenged the policy at the start. The Girondin government was certain that people across the world—particularly Americans—shared its revolutionary zeal and would assist its crusade to extend republicanism. Genet was instructed to conclude with the United States an "intimate concert" to "promote the Extension of the Empire of Liberty," holding out the prospect of "liberating" Spanish America and opening the Mississippi. Failing this, he was to act on his own to liberate Canada, the Floridas, and Louisiana, and was empowered to issue commissions to Americans to participate. He was also to obtain a $3 million advance payment on America's debt to France. While these matters were under negotiation, he was to secure the opening of U.S. ports to outfit French privateers and bring in enemy prizes. The instructions, if implemented, would have made the United States a de facto ally against England.31

The new minister's unsuitability for his position exceeded his chimerical instructions. A gifted linguist and musician, handsome, witty and charming, he was also a flamboyant and volatile individual who had already been thrown out of Catherine the Great's Russia for diplomatic indiscretions. Inflamed with the crusading zeal of the Girondins, he poorly understood the nation to which he was accredited, assuming mistakenly that popular sympathy for France entailed a willingness to risk war with England and that in the United States, as in his country, control of foreign relations resided with the legislature.

From the moment he came ashore, Genet was the proverbial bull in the china shop. Landing in Charleston, South Carolina, where he was widely feted by the governor and local citizenry, he commissioned four privateers that soon brought prizes into U.S. ports. The lavish entertainment he enjoyed along the land route to Philadelphia confirmed his belief that Americans supported his mission, a conclusion reinforced by early meetings with Jefferson. Hoping to persuade Genet to proceed cautiously lest he give Hamilton reason to adopt blatantly anti-French policies, the secretary of state took the minister into his confidence and spoke candidly, even indiscreetly, about U.S. politics, encouraging the Frenchman's illusions and ardor.

In fact, the two nations were on a collision course. After long and sometimes bitter debates and frequently over Jefferson's objections, the cabinet had hammered out a neutrality policy that construed American obligations under the French alliance as narrowly as possible. The United States denied France the right to outfit privateers or sell enemy prizes in its ports and ordered the release of prizes already brought in. It flatly rejected Genet's offer of a new commercial treaty, as well as his request for an advance payment on the debt, and ordered the arrest of Americans who had enlisted for service on French privateers.

The U.S. policies violated the spirit, if not the letter, of the alliance, giving Genet grounds for protest, but his blatant defiance of American orders undercut his cause. He responded intemperately to Jefferson's official statements, insisting that they did not reflect the will of the American people. Ignoring U.S. instructions, he commissioned a privateer, La Petite Democrate, under the government's nose in Philadelphia and began organizing expeditions to attack Louisiana by sea and land, the latter to be manned primarily by Kentuckians headed by revolutionary war hero George Rogers Clark. In defiance of Jefferson's request to delay sailing of the ship and while the cabinet was heatedly debating whether to forcibly stop its departure, he ordered La Petite Democrate out of reach of shore batteries and eventually to sea. Responding to repeated official protests, he threatened to take his case to the nation over the head of its president.

Genet's actions sparked a full-fledged, frequently nasty debate in the country at large. Supporters of France and its minister accused the government of pro-British sympathies and monarchical tendencies, calling them "Anglomen" and "monocrats." Those who defended the government denounced the opposition as tools of France and radical revolutionaries. The outlines of political parties began to take form. Jeffersonians took the name Republicans, Hamiltonians became Federalists. Political dialogue was impassioned, street brawls were not uncommon, and old friendships were severed. Newspapers aligned with Hamilton or Jefferson and frequently encouraged by them waged virulent war, debating the basic principles of government while indulging in name-calling and calumny from which even the demigod Washington was not immune. Discussions in the cabinet reflected the increasingly bitter mood of the nation, provoking a harried and thin-skinned president (the first of many holders of the office, in this regard) to explode that "by god he had rather be in his grave than in his present situation."32

The Genet affair ended in anticlimax and irony. By July 1793, the administration felt compelled to ask for his recall, even Jefferson agreeing that the appointment had been "calamitous" and confiding in Madison that he saw the "necessity of quitting a wreck which could not but sink all who cling to it."33 Hamilton and Knox sought to do it in a way that would discredit the French minister and his American supporters. Washington wisely sided with Jefferson, seeking to do so without alienating France. By the time the United States asked for his recall, the Girondins had been replaced by the Jacobins, who, though more radical at home, did not share their predecessors' zeal for a global crusade. Suffering disastrous defeats on land and sea and in desperate need of American food, the new government readily acceded, denouncing Genet's "giddiness." In one of those bizarre twists that marked the politics of the French Revolution, it accused him of complicity in an English plot. Had he returned home, he would likely have been guillotined. Aware of what awaited him, Genet requested, and as a humanitarian gesture was granted, asylum in the United States.34 He lived out his life as a gentleman farmer and unsuccessful amateur scientist in New York, becoming an American citizen in 1804 and marrying the daughter of New York governor George Clinton.

Genet's shenanigans were generally counterproductive. The escape of La Petite Democrate did not provoke British reprisals; the minister's grand scheme for the liberation of Louisiana quickly collapsed from shortage of funds and lack of American support. On the other hand, the cautious and at least mildly pro-British definition of neutral obligations set forth piecemeal by the Washington administration was enacted into law in 1794, forming the basis for U.S. neutrality policies into the twentieth century. Frustration with Genet contributed to Jefferson's decision to leave office in late 1793, removing from the cabinet a voice sympathetic to France and eventually contributing to a tilt in policy toward Britain.

More than anything else, the Genet mission exposed the fragility of American neutrality, the extent to which the European powers would go to undermine it, and the depth of internal conflict on foreign policy. It marked the beginning, rather than the end, of a twenty-year effort to steer clear of the European war while profiting from it, and it divided Americans into two deeply antagonistic factions.

Even while the Genet affair occupied center stage, the United States and Britain edged toward war. Still sometimes portrayed by Americans as the ruthless aggression of an arrogant great power against an innocent and vulnerable nation, the crisis of 1794 was considerably more complex in its origins. It provides, in fact, a classic example of the way in which conflicts of interest, exacerbated by intense nationalism on one side, a lack of attention on the other, and the ill-advised actions of poorly informed and sometimes panicky officials miles from the seat of government can create conditions for war even when the governments themselves have reason to avoid it. In this instance, war was averted, but only narrowly and only because both nations and especially the United States found compelling reason for restraint.

By early 1794, the long-simmering conflict along the Great Lakes threatened a clash of arms. Increasingly concerned with the explosive frontier, the British after St. Clair's defeat devised a "compromise" that would have set aside specified lands for the Indians in territory claimed by the United States. By this time, however, neither of the other parties was inclined to negotiate. Buoyed by their victory, the Indians demanded lands from the Canadian border to the Ohio River and murdered under flags of truce several U.S. agents sent to treat with them. Americans never understood the pride and suspicion with which the Indians viewed them. They would concede only limited territory to people Hamilton dismissed as "vagrants." Even after a humiliating defeat, they patronized the victors. They blamed the British for the tribes' exorbitant claims and violently protested their interference in what they viewed a purely internal matter.35

In the absence of a settlement, tensions flared. When nervous British officials in Canada learned that the United States was preparing another military expedition to be commanded by General "Mad Anthony" Wayne of Revolutionary War fame, they feared attacks on their frontier posts. Without London's approval, they incited the Indians to resist American advances. As a "defensive" measure, they sent troops to the Maumee River near present-day Detroit. What the British viewed as defensive, Americans regarded as further evidence of British perfidy and provocation. As Wayne moved north and British forces south, there was much loose talk of war.

Conflicts over issues of neutrality posed even more difficult problems. From its birth as a nation, the United States had claimed the right to trade with belligerents in non-contraband and defined contraband narrowly to include only specifically military items such as arms and ammunition. It also endorsed the principle that free ships make free goods, meaning that the private property of belligerents aboard neutral ships was immune from seizure. The United States insisted that these "rights" had sanction in international law and incorporated them into treaties with several European countries. But they served the national interest as well. Desperately in need of U.S. foodstuffs, France purchased large quantities of grain and permitted American ships to transport supplies from its West Indian colonies to its home ports, a right generally denied under mercantilist doctrine. Hundreds of American ships swarmed into the Caribbean and across the Atlantic to "fatten on the follies" of the Old World.

Americans' quest for profits ran afoul of Britain's grand strategy. Recognizing France's dependence on external sources of food, the British government set out to starve its enemy into submission, blockading French ports, broadening contraband to include food, and ordering the seizure of American ships carrying grain to France. The British did not want to drive the United States into the arms of France and thus agreed to purchase confiscated grain at fair prices. Preoccupied with the European war, increasingly alarmed at the burgeoning American trade with France, and badly misjudging the Washington administration's handling of Genet, they implemented their strategy in a high-handed and often brutal manner that threatened to provoke war. Without any warning and frequently exceeding their instructions, overzealous British officials in the West Indies seized 250 ships. Egged on by a system that permitted the captors personally to profit from such plunder, ship captains boarded American vessels, stripped them of their sails, and tore down their colors. Hastily assembled kangaroo courts condemned ships and cargoes. Captains and crews were confined, often without provisions. Some Americans were impressed into the Royal Navy; others died in captivity. Britain justified its efforts to curtail trade with France through its so-called Rule of 1756 declaring that trade illegal in time of peace was illegal in time of war. British officials later admitted, however, that the ship seizures of 1794 far exceeded the bounds of this rule.36

London's actions stirred powerful resentment in the United States. What seemed to Britons essential acts of war appeared to Americans a threat to their prosperity and a grievous affront to their dignity as an independent nation. Angry mobs in seaport cities attacked British sailors. In Charleston, a crowd tore down a statue of William Pitt the Elder that had survived the Revolution. Congress assembled in early 1794 in a mood of outrage. Madison's proposals in the House of Representatives for discrimination against British commerce failed in the Senate by the single vote of Vice President John Adams. Even Federalists spoke of war. An angry Congress proceeded to impose a temporary embargo on all foreign shipping and to discuss even more drastic measures such as repudiation of debts owed Britain and creation of a navy to defend American shipping.

The crisis of early 1794 posed a dilemma for the Washington administration. Most top officials regarded a British victory as essential to the preservation of stable government in Europe and hence to the well-being of the United States. On the other hand, they appreciated and indeed shared the rising public anger toward Britain and perceived that their political foes might use it to discredit them. Acquiescence in British high-handedness was unthinkable. Should Madison's quest for economic retaliation succeed, on the other hand, it might provoke a disastrous war. Without precedent to guide him, Washington took the initiative in addressing the crisis, agreeing to Hamilton's proposal to send a special mission to London to negotiate a settlement that might avert war and silence the opposition. Chief Justice John Jay, an experienced diplomat and staunch Federalist, was selected for the mission.37

Washington and his advisers perceived that an agreement might be costly. As was customary in a time when communications were slow and uncertain, Jay was given wide latitude. The only explicit requirements were that he agree to nothing that violated the French treaty of 1778 and that he secure access to trade with the British West Indies, both regarded as essential to appease the domestic opposition. He was also instructed to seek compensation for the recent seizures of vessels and cargoes, to settle issues left from the 1783 treaty, particularly British retention of the Northwest posts, and to conclude a commercial treaty that would resolve sticky questions of neutral rights. The administration appears not to have expected major concessions on matters concerning neutrality. It hoped rather to win enough in other areas to make concessions to the British palatable to its critics.

The British too were in a conciliatory mood, although within distinct limits. Preoccupied with events in Europe and with a political crisis at home, officials were caught off guard by the furious American reaction to ship seizures in the West Indies. Their military position on the Continent precarious, they had no need for war with the United States. Even before Jay arrived in London, they revoked the harsh orders that had led to the West Indian ship seizures. The government received Jay cordially. Its chief negotiator, Lord Grenville, sought to establish an effective working relationship with him. British leaders were prepared to make concessions to avoid conflict with the United States. To have given in on neutral rights would have denied them a vital weapon against France at a critical time, however, and on such issues they stood firm.

The settlement worked out during six months of sporadic and tedious but generally cordial negotiations reflected these influences. The British willingly abandoned an untenable position, agreeing to evacuate the Northwest posts. The treaty was silent on their relations with the Indians. To the annoyance of southern planters, it said nothing about compensation for slaves carried off during the Revolution. A boundary dispute in the Northeast and the question of pre-Revolutionary debts owed by Americans to British creditors were referred to mixed arbitral commissions.38

In view of its long-standing opposition to commercial concessions of any sort, Britain was surprisingly liberal in this area. In fact, the home island and especially the colonies depended on trade with the United States. The British Isles were opened to Americans on a most-favored-nation basis. American ships were permitted into British India with virtually no restrictions and also gained access to the much-coveted West Indian trade, although vessels were restricted to less than seventy tons and the Americans were forbidden to reexport certain products including even such items produced in the United States. On balance, for a nation still committed to mercantilist principles, the concessions were generous.

As Hamilton and Jay had feared, Britain stood firm on neutral rights. Grenville readily agreed to compensate the United States for ships and cargoes seized in the West Indies but would go no further. Jay conceded the substance, if not the principle, of British definitions of contraband and the Rule of 1756. For all practical purposes, he scrapped the principle of free ships and free goods and agreed to admit British privateers and prizes to American ports, a direct violation of the 1778 treaty.

Critics then and later have argued that Jay gave up more than was necessary and secured less than he should have in return. He was too eager for a settlement, they claim, and refused to hold out, bargain, or exploit his strengths and British weaknesses. Some scholars have also contended that Hamilton undercut Jay's position by confiding in the British minister to Washington, George Hammond, that the United States would not join a group of nations then forming an armed neutrality to defend their shipping against Britain.39 As in earlier cases, Hamilton's machinations cannot be condoned, but, in this instance, their practical effects appear limited. The armed neutrality lacked support from major European neutrals such as Russia. In any event, the United States had little to contribute or gain from it. Hamilton's assurances reached London only after the negotiations were all but concluded and told the British little they did not know. Jay was indeed anxious for a settlement. He might have gained a bit more by dragging out the negotiations. But on neutral rights Britain could not be moved. Their backs to the wall on the Continent and in the Caribbean, London officials could not relinquish their most effective weapon. Without an army or navy and standing to lose huge revenues from war with England, the United States could not make them do so.

Although desperate for peace, Hamilton and Washington were themselves keenly disappointed with the terms. For a time, the president hesitated to submit the document to the Senate, but he eventually rationalized that a bad treaty was better than none at all. He sent Jay's handiwork to the upper house without any recommendation, but he was so concerned with possible public reaction that he insisted it be considered in secret. The Senate approved the treaty by the barest majority, 20–10, and then only after the article on West Indian trade was excised because the limits on tonnage effectively eliminated American ships from the trans-Atlantic trade.

No other treaty in U.S. history has aroused such hostile public reaction or provoked such passionate debate, even though, ironically, the Jay Treaty brought the United States important concessions and served its interests well. The explanation must be sought not only in rampant political partisanship but also in ideology and the insecurities of a new and fragile nation.40 The treaty provoked such anger because it touched Americans in areas where they were most sensitive. The mere fact of negotiations with Britain was difficult for many to accept. To some Americans, Jay's concessions smacked of subservience. Moreover, to an extent that was not true in Europe, foreign policy in the United States was subject to debate by a public whose understanding of the issues and mechanisms was neither sophisticated nor nuanced, that sought clear-cut and definitive solutions, and defined outcomes in terms of victory and defeat. By the very nature of diplomacy, such high expectations were bound to be disappointed and the results to be received with something less than enthusiasm. American insecurity thus manifested itself in a frenzy of anger and an outpouring of patriotic fervor.

When the text of the treaty was published by a Republican newspaper less than a week after approval by the Senate, popular indignation swept the land. The aura of secrecy that had shrouded the treaty and its disclosure on the eve of emotional July 4 celebrations heightened the intensity of the reaction. Even in Federalist strongholds, the document and its author were publicly condemned. In towns and villages across the country, incensed citizens lowered flags to half mast and hangmen ceremoniously destroyed copies of the treaty. Burning effigies of that "damned arch traitor Jay" lit the night. The British minister was publicly insulted by a hostile crowd. When Hamilton took the stump in New York to defend the treaty, he was struck by a stone. Once again, the venerable Washington came under attack, irate critics labeling him a dupe and a fool and even accusing him of misusing public funds.

Outraged by the terms of the treaty and smelling political blood, Republican leaders fanned the popular indignation. Southerners and westerners, suspicious of Jay since his negotiations with Spain a decade earlier, saw their worst fears confirmed in the obnoxious document. Failure to deal with the issue of confiscated slaves and submission of the debt controversy to an arbitral commission touched southern interests directly. From the Republican point of view, the commercial treaty and the cave-in on neutral rights totally undermined the principles essential for a truly independent status for the United States. By prohibiting interference in Anglo-American trade for ten years, it surrendered the instrument—commercial discrimination—needed to attain that end. It represented a humiliating capitulation to the archenemy Britain and a slap in the face to France. Madison and Jefferson saw treaties as a means to reform the balance-of-power system and international law. To them, the Jay Treaty represented an abject retreat to the old ways. It was "unworthy [of] the voluntary acceptance of an Independent people," Madison fumed.41 Jefferson was more outspoken, denouncing the treaty as a "monument of folly and venality," an "infamous act," nothing more than a "treaty of alliance between England and the anglomen of this country against the legislature and people of the United States." Those who had been "Samsons in the field and Solomons in the council," he privately exclaimed, "have had their heads shorn by the harlot England."42

The treaty survived the storm. Hamilton, now a private citizen, joined Jay in mounting a vigorous and generally effective defense of their handiwork. Despite their compunctions about mobilizing a presumably ignorant public, the Federalists effectively rallied popular support, highlighting the concessions made by Britain and emphasizing that, whatever its deficiencies, the treaty preserved peace with the nation whose friendship was essential to U.S. prosperity and well-being.43 Perhaps persuaded by Hamilton and Jay, Washington overcame persistent reservations about ratifying the treaty. The bitter personal attacks on him by foes of the treaty probably contributed to his decision. A harried president finally signed the Jay Treaty in August 1795.

Defeated in the Senate and by the executive, the Republicans mounted a bitter rearguard effort that would delay implementation of the treaty for almost a year and raise important constitutional questions. Insisting that the House also had the power to approve treaties, a position Jefferson himself had explicitly rejected some years earlier, the Republican-controlled lower chamber demanded that the president submit to it all documents relating to negotiation of the treaty. Washington refused, setting an important precedent on executive privilege. The House quickly approved a resolution reaffirming its right to pass on any treaty requiring implementing legislation. Some Republicans shied away from direct confrontation with the president, however, and in April 1796 the House appropriated funds to implement the treaty by a narrow margin of three votes, setting a precedent that has never been challenged.

Remarkable and fortuitous economic and diplomatic gains facilitated public acceptance of the treaty. There is no better balm for wounded pride than prosperity. As a neutral carrier for both sides, the United States enjoyed a major economic boom in the aftermath of the treaty. Exports more then tripled between 1792 and 1796. "The affairs of Europe rain riches on us," one American exulted, "and it is as much as we can do to find dishes to catch the golden shower."44

While Jay was negotiating in London and the treaty was being debated at home, Wayne settled the future of the Northwest on U.S. terms. Following the St. Clair debacle, he gathered an imposing army eventually numbering 3,500 men and prepared his campaign with the utmost care. In August 1794, he routed a small force of Indians at Fallen Timbers near British-held Fort Miami. Despite earlier inciting them to battle, the British refused to back the Indians or even allow them into the fort when Wayne had them on the run. After a tense standoff outside the fort where, perhaps miraculously, neither Britons nor Americans fired a shot, Wayne systematically plundered Indian storehouses and burned villages in the Ohio country. In August 1795, he imposed on the defeated and dispirited tribes the Treaty of Greenville that confined them to a narrow strip of land along Lake Erie. It was certainly not expansion with honor, but in the eyes of most Americans the ends justified the means. Wayne's campaign crippled the hold of Indians and British in the Old Northwest, restoring the prestige of the American government and strengthening its hold on the Ohio country. Removal of the British was the last step in completing the process Wayne had begun, a point defenders of the Jay Treaty hammered home in speech after speech.45

An unanticipated and quite astounding diplomatic windfall from the Jay Treaty also eased its acceptance. A declining power, Spain found itself in a precarious position between the major European belligerents. Allied for a time with Britain, it changed sides when the advance of a French army into the Iberian peninsula threatened its very survival. Fearing British reprisals and suspecting—incorrectly, as it turned out—that the Jay Treaty portended an Anglo-American alliance that might bring combined expeditions against Spanish America, a panicky Madrid government moved quickly to appease the United States. The U.S. minister, Thomas Pinckney, was astute enough to seize the opportunity. In the Treaty of San Lorenzo, signed in October 1795 and sometimes called Pinckney's Treaty, Spain recognized the boundary claimed by the United States since 1783. It also granted the long-coveted access to the Mississippi and for three years the right to deposit goods at New Orleans for storage and transshipment without duties. Resolving at virtually no cost to the United States issues that had plagued Spanish-American relations and threatened the allegiance of the West, Pinckney's Treaty pacified the restless westerners and made the Jay Treaty more palatable.46

From the vantage point of more than two hundred years, the verdict on Jay's Treaty is unambiguous. Jay was dealt a weak hand and might have played it better. In seeking and pushing the treaty, Hamilton and Jay acted for blatantly partisan and self-serving reasons, promoting their grand design for foreign relations and domestic development. Their dire warnings of war may have been exaggerated. The most likely alternative to the treaty was a continued state of crisis and conflict that could have led to war. On the other hand, Republican ranting was also driven by partisanship and was certainly overstated. Diplomacy by its very nature requires concessions, a point Americans even then were inclined to forget. The circumstances of 1794 left little choice but to sacrifice on neutral rights. Jay secured concessions Jefferson could not get that turned out to be very important over the long run. Most important, Britain recognized U.S. independence in a way it had not in 1783. Rarely has a treaty so bad on the face of it produced such positive results. It initiated a period of sustained prosperity that in turn promoted stability and strength. It bound the Northwest and Southwest to a still very fragile federal union. It bought for a new and still weak nation that most priceless commodity—time.

Whatever its long-term benefits, the treaty afforded the United States no immediate respite. Conflict with France dominated the remainder of the decade, provoking a sustained diplomatic crisis, blatant French interference in American internal affairs, and an undeclared naval war. The war scare of 1798 heightened already bitter divisions at home. Federalist exploitation of the rage against France for partisan advantage provoked fierce Republican reaction that could not be silenced through repression. Suspicions on each side ran wild, Federalists claiming that Republicans were joining with France to bring the excesses of the French Revolution to America, Republicans insisting that the Federalists, allied with Britain, were seeking to destroy republicanism at home. The war scare also set the Federalists squabbling among themselves, producing cabinet intrigues and rumors of plots akin to coups.

Absorbed with the European war and its own internal politics, France viewed the United States as a nuisance and possible source of exploitation rather than a major concern. The Directory then in power represented the low point of the revolution, unpopular, divided against itself, and rife with corruption. French policy toward the United States, if indeed it could be called that, reflected the whim of the moment, a need for food, a lust for money. The French naturally protested the Jay Treaty, claiming they had been "betrayed and despoiled with impunity." But the treaty was as much pretext as cause for attacks on the United States that were reckless to the point of stupidity. Flushed with victories on the Continent, France arrogantly toyed with the United States and plundered its shipping, outraging a profoundly insecure people whose nerves were already frayed from years of mistreatment at the hands of the great powers.47

Following the Jay Treaty, France retaliated against the United States. Genet's successors, Joseph Fauchet and Pierre Adet, lobbied vigorously to defeat the treaty in the Senate and House, offering bribes to some congressmen. Failing, they tried intimidation to mitigate its effects. Proclaiming that the treaty of 1778 was no longer in effect and hinting ominously at a severance of diplomatic relations, they insisted that U.S. concessions to Britain compelled them to scrap the principle of free ships, free goods. They seized more than three hundred American ships in 1795 alone. Hoping to exploit popular anger with Jay's Treaty, they used the threat of war to secure the election of a more friendly government. Adet interfered in the election of 1796 in a way not since duplicated by a foreign representative by warning that war could be avoided only by the election of Jefferson. A furious Washington denounced French treatment of the United States as "outrageous beyond conception."48

French meddling provoked a sharp presidential response in the form of Washington's Farewell Address. Drafted partly by Hamilton, the president's statement was at one level a highly partisan political document timed to promote the Federalist cause in the approaching election. Washington's fervid warnings against the "insidious wiles of foreign influence" and "passionate attachments" to "permanent alliances" with other nations unmistakably alluded to the French connection and Adet's intrigues. They were designed, at least in part, to discredit the Republicans.49

At another level, the Farewell Address was a political testament, based on recent experience, in which the retiring president set forth principles to guide the nation in its formative years. Washington's admonitions against partisanship reflected his sincere and deep-seated fears of the perils of factionalism at a delicate stage in the national development. His references to alliances set forth a view common among Americans that their nation, founded on exceptional principles and favored by geography, could best achieve its destiny by preserving its freedom of action. Although it would later be used as a justification for isolationism, the Farewell Address was not an isolationist document. The word isolationism did not become fixed in the American political lexicon until the twentieth century. No one in the 1790s could have seriously entertained the notion of freedom from foreign involvement.50 Washington vigorously advocated commercial expansion. He also conceded that "temporary alliances" might be required in "extraordinary emergencies." Influenced by experience dating to the colonial period, he stressed the importance of an independent course free of emotional attachments and wherever possible binding political commitments to other nations. When the country had grown strong and the interior was tied closely to the Union, it would be able to fend off any threat, a blueprint for future empire.51

For whatever reason, Americans heeded Washington's warnings, and France's efforts to swing the election of 1796 backfired. The Federalists took the high ground of principle and nationalism, charging their opponents with serving a foreign power. Although it is impossible to weigh with any precision the impact of Adet's interference, it likely contributed to the Federalist victory. Despite a split between those Federalists supporting Vice President John Adams and those, including Hamilton, who preferred Thomas Pinckney, Adams won seventy-one electoral votes to sixty-eight for Jefferson. At a time when the runner-up automatically became vice president, the nation experienced the anomaly of its two top officials representing bitterly contending parties.

Failing to "revolutionize" the U.S. government, France sought to punish the upstart nation for its independence. Proclaiming that it would treat neutrals as neutrals allowed England to treat them, Paris officially sanctioned what had been going on for months, authorizing naval commanders and privateers to seize ships carrying British property. They quickly equaled the haul of 1795. Atrocities sometimes accompanied the seizures—one American ship captain was tortured with thumbscrews until he declared his cargo British property and liable for seizure. By 1797, French raiders boldly attacked U.S. ships off the coast of Long Island and Philadelphia. France also refused to receive the newly appointed U.S. minister, Charles C. Pinckney, insisting that an envoy would not be accredited until the United States redressed its grievances.52

In seeking to intimidate the United States, France badly misjudged the mood of the nation and the character of its new president. Sixty-one years old, vain, thin-skinned, and impulsive, John Adams was also a man of keen intelligence and considerable learning. In many ways, he was the most stubbornly independent of the Founders. Pessimistic in his view of human nature and conservative in his politics, he had been skeptical of the French Revolution from the outset.53 A staunch nationalist, he reacted indignantly to French high-handedness. And some of his advisers would have welcomed war. In awe of his predecessor, he retained not only the cabinet system but also Washington's cabinet: the querulous and narrow-minded Timothy Pickering as secretary of state and Oliver Wolcott, the mediocre Hamilton confidant, as secretary of the treasury. Adams never shared the pro-British sympathies of his colleagues. Short and plump, by his own admission "but an Ordinary Man," he lacked his illustrious predecessor's commanding presence. Unsure of himself in the presidency and deeply angered by France, he tolerated his advisers' virulently anti-French policies to the brink of war.

Adams's initial approach to France combined a willingness to employ force with an openness to negotiations. Shortly after taking office, he revived long-dormant plans to build a navy to protect U.S. shipping. Still hoping to avert war, he emulated Washington's 1794 approach to England by dispatching to France a special peace mission composed of John Marshall, Elbridge Gerry, and Charles C. Pinckney. He instructed his commissioners to ask compensation for the seizures of ships and cargoes, secure release from the articles of the 1778 treaty binding the United States to defend the French West Indies, and win French acceptance of the Jay Treaty. They were authorized to offer little in return.

Given American terms, a settlement would have been difficult under any circumstances, but the timing was especially inopportune. Revolutionary France was at the peak of its power. Napoleon Bonaparte had won great victories on the Continent. Britain was isolated and vulnerable. France was willing to settle with the United States, but it saw no need for haste. In need of money and accustomed to manipulating the small states of Europe through a "vast network of international plunder," the Directory set out to extort what it could from the United States. Its minister of foreign relations, the notorious Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, an aristocrat, former Roman Catholic bishop, and notorious womanizer, had lived in exile in the United States and had little respect for Americans. Certain that the new nation "merited no more consideration than Genoa or Geneva," he preferred at least for the moment a condition he described as "half friendly, half hostile," which permitted France to enrich itself by looting U.S. ships.54 A master of survival in the hurly-burly of French politics, conniving, above all venal, Talleyrand also hoped to enrich himself at American expense. He treated Adams's commissioners as representatives of a European vassal state. When the delegation arrived in France, it was told by mysterious agents identified only as X, Y, and Z that negotiations would proceed more smoothly if the United States paid a bribe of $250,000 and loaned France $12 million.55

The so-called XYZ mission failed not because France insulted American honor but because the U.S. diplomats concluded that no settlement was attainable. Pinckney's much publicized response—"No, no, not a sixpence"—did not reflect the initial view of the commissioners. They were prepared to pay a small douceur if persuaded that negotiations could succeed. Although doubtful the U.S. treasury could sustain a loan of the magnitude requested, they considered asking for new instructions if they could convince France to stop attacking American ships. Eventually, however, it became clear that Talleyrand had no intention of easing the pressure or compensating their country for earlier losses. Certain that their mission was hopeless, Pinckney and Marshall returned home, playing for all it was worth the role of aggrieved republicans whose honor had been insulted by a decadent old world.

The XYZ Affair set off a near hysterical reaction in the United States, providing an outlet for tensions built up over years of conflict with the Europeans. Adams was so incensed with the treatment of his diplomats that he began drafting a war message. Publication of correspondence relating to the mission unleashed a storm of patriotic indignation. Angry crowds burned Talleyrand in effigy and attacked supposed French sympathizers. Memorials of support for the president poured in from across the country. The once popular tricolor cockade gave way to the more traditional black cockade, French songs to American. Frenzied public gatherings sang new patriotic songs such as "Hail Columbia" and "Adams and Liberty" and drank toasts to the popular slogan "Millions for defense but not one cent for tribute." Militia rolls swelled. Old men joined patriotic patrols, while little boys played war against imaginary French soldiers. Exulting in the "most magical effects" of the XYZ furor on public attitudes, Federalists fanned the flames by disseminating rumors of French plans to invade the United States, incite slave uprisings in the South, and burn Philadelphia and massacre its women and children. Basking in the glow of unaccustomed popularity, Adams stoked the martial spirit. "The finger of destiny writes on the wall the word: 'War,' " he told one cheering audience.56

The president eventually settled for a policy of "qualified hostility." Some Republicans challenged the war fever—Jefferson sarcastically talked of the "XYZ dish cooked up by Marshall" to help the Federalists expand their power.57 With only a narrow majority in the House, Adams feared that a premature declaration might fail. Moreover, he learned from reliable sources that France did not want war, giving him pause. Although he remained willing to consider war, he determined to respond forcibly to French provocations without seeking a declaration. A firm American posture might persuade France to negotiate on more favorable terms or provoke the United States to declare war. Continued conflict might eventually goad Congress into acting.

Adams thus pushed through Congress a series of measures that led to the so-called Quasi-War with France. The 1778 treaty was unilaterally abrogated, an embargo placed on trade with France. Secretary of State Pickering reversed Washington's policy toward Saint-Domingue, cutting a deal with the independent black republic to restore trade and employing warships to help solidify its power.58 Congress approved the creation of a separate Department of the Navy, authorized the government to construct, purchase, or borrow a fleet of warships, approved the arming of merchant vessels and the commissioning of privateers, and permitted U.S. ships to attack armed French vessels anywhere on the high seas. Over the next two years, the United States and France waged an undeclared naval war, much of it in the Caribbean and West Indies, the center of U.S. trade with Europe and the focal point of British and French attacks on American shipping. Supported by a fleet of armed merchant-men, the infant U.S. Navy drove French warships from American coastal waters, convoyed merchant ships into the West Indies, and successfully fought numerous battles with French warships. Americans cheered with especial nationalist fervor the victory of Capt. Thomas Truxtun's Constellation over Insurgente, reputedly the fastest warship in the French navy.59

Adams's more belligerent advisers saw in the conflict with France a splendid opportunity to achieve larger objectives. The war scare provided a pretext for the standing army Federalists had long sought. In the summer of 1798, Congress authorized an army of fifty thousand men to be commanded by Washington in the event of hostilities. Federalists in the cabinet and Senate also sought to rid the nation of recent immigrants from France and other countries who were viewed as potential subversives—and even worse as Republican political fodder—enacting laws making it more difficult to acquire American citizenship and permitting the deportation of aliens deemed dangerous to public safety. Striking directly at the opposition, the Federalists passed several vaguely worded and blatantly repressive Sedition Acts that made it a federal crime to interfere with the operation of the government or publish any "false, scandalous and malicious writings" against its officials. Egged on by Hamilton, some extremists fantasized about an alliance with England and joint military operations against the Floridas, Louisiana, and French colonies in the West Indies.60

The war scare of 1798 waned as quickly as it had waxed. When the hostile U.S. reaction made clear the extent of his miscalculations, Talleyrand shifted direction. French officials feared driving the United States into the arms of England, solidifying the power of the Federalists, and denying France access to vital products. Already negotiating with Spain an agreement to regain Louisiana as part of a larger design to restore French power in North America, nervous officials perceived that war with the United States would invite an assault on Louisiana and destroy France's dreams of empire before implementation had begun. The demonstrated ability of the United States to defend its commerce reduced the profits from plunder, rendering the "half friendly, half hostile" policy counterproductive. As early as the summer of 1798, Talleyrand began sending out signals of reconciliation. His message grew stronger by the end of the year.

As belligerent as anyone at the outset, Adams in time broke with his more extreme colleagues. Gerry, who had remained in Paris, the Quaker George Logan, then on an unofficial and unauthorized peace mission in France, Adams's son John Quincy, and other U.S. diplomats in Europe all reported unmistakable signs of French interest in negotiations. Adams had never taken seriously the threat of a French invasion of the United States. Lord Nelson's destruction of the French fleet at Aboukir Bay in Egypt in October 1798 rendered it a practical impossibility. There was "no more prospect of seeing a French army here, than there is in Heaven," the president snarled.61