Canto XII, ll. 46–51

| Ma ficca li occhi a valle, ché s'approccia | But probe the valley with your sight, for we |

| la riviera del sangue in la qual bolle | are approaching the river of blood, in which are boiling |

| qual che per vïolenza in altrui noccia | those who harm others with violence. |

| Oh cieca cupidigia e ira folle, | Oh blind cupidity and mad rage, |

| Che sì ci sproni ne la vita corte | that so spur us in this short life, |

| E ne l'etterna poi sì mal c'immole! | and then in the eternal one, cook us so evilly! |

As we have just seen, the Gradations of Evil scale includes a category where evil is not present at all, plus twenty-one others. The higher the number, the more likely people will use the word evil in describing the murders and other acts belonging to that category. We then reduced those twenty-one categories to five groups: the impulsive without psychopathic traits, the impulsive with a few psychopathic traits, those showing malice aforethought and many psychopathic traits, psychopaths committing multiple violent crimes, and finally, psychopaths committing either torture alone or else serial sexual murders that also include torture.

To simplify matters even further, we could speak of just two very broad groups: those with few or no psychopathic traits versus those with many or full-blown psychopathic traits. Another broad division concerns those who acted on impulse and those who planned the hurt or the violence they then committed. Here we will turn our attention to impulsive persons whose evil acts were not accompanied by psychopathic traits, or, if they were, the traits are minor. As always, I am using the word evil here in response to the reactions of the public in general and to the reactions of the people who came to be involved with the various cases, including journalists, members of the court, and relatives of the victims.

In the courts and in books about crime, certain phrases are used over and over that have almost identical meaning. An impulse crime may also be spoken of as a crime of passion or a crime done in the heat of passion. The “passion” may concern a love relationship and sexual passion or may mean no more than a strong emotion of any kind, such as anger or rage. A less commonly used word is expressive—which merely indicates that the act was done by way of expressing some intense feeling. Crimes preceded by planning, and done with malice aforethought—that is, with the conscious intention of hurting another person—are often called instrumental crimes. This does not mean the crime was carried out using an instrument; rather, the crime itself was the “instrument” for achieving some goal. Hiring a hit man to kill a spouse so as to free oneself to be with a lover is, for example, the “instrument” the killer uses to carry out his or her plan of a new life with the other partner. This is quite different from the situation, mentioned in the last chapter, where a woman tells her husband “out of the blue” she is leaving him, and, as she tries to leave the house, he kills her with a blunt object. In that example, the crime is said to be impulsive/expressive/done in the heat of passion.

JEALOUSY AND OTHER CRIMES OF PASSION

People are more tempted to use the word evil when speaking of a crime that not only involves great cruelty but is also preceded by conscious intention. The same is true for acts of cruelty, often carried out within a family, that go unnoticed because the authorities are not summoned. Crimes of intention are placed under the heading of instrumental. The term premeditated is regularly used in the same connection.1 Rape, kidnap, and robbery would come under the heading of instrumental crimes. Acts of this sort are most often premeditated, in contrast to crimes or other damaging actions that are called expressive, where the common characteristics are lack of forethought and spontaneity. These acts are said to have been done in the heat of passion.2

Before people regard an event as evil, they are apt to take into consideration the motive that seemed to have set the harmful act in motion. Certain motives are regarded as more understandable and more forgivable; others are regarded as more vile and inhuman.

To get a better grasp on why we tend in our minds to create a hierarchy of more or less forgivable acts—in effect, lesser or greater evils—we can take a brief page from psychiatry; specifically, from the comments of Sigmund Freud.

Toward the end of his long life, Freud was approached by a journalist who inquired of the great man what life was all about. I suspect the man expected a rather lengthy disquisition—distilled presumably from Freud's half century of exploration into the human mind. What the journalist got was two words. Well, three, if you count the “and.” Freud said: “Liebe und Arbeit”—Love and Work. When matters go very wrong in the sphere of love, we may find jealousy. And where jealousy is extreme, serious crimes including murder can be the outcome and may occur quite suddenly—literally in the heat of passion. Stalking an intimate partner following a rejection is another act of love-gone-wrong—one that may also escalate to a serious crime or murder, though here there is more conscious planning—making the stalker's actions “instrumental.”

In everyday speech people do not always make fine distinctions between jealousy and envy. This was apparently so in Old Testament times, when the term qin'ah was used for both words and also meant “ardor” or “heat,” in the emotional sense. The equation between passion and heat goes back to our earliest days. The equation worked (as it still does) in both directions: we burn with passionate love; if the love turns sour, we burn with anger (and the switch can happen in the fraction of a second). The Romans also made little distinction between jealousy and envy, using the word invidia for both. For them, the root meaning was to see (vidŸre) in a negative way; figuratively, to look upon someone with the evil eye. But currently envy is usually reserved for two-person situations—where you have something (your Ferrari) that I wish I had (instead of my Chevy)—in this case, coveting your neighbor's car. Jealousy refers more to a three-person situation: I resent you because I thought you loved me, but now I see you have turned away from me and love another. I have lost you and I hate the other for having taken you from me—or I hate you for having deserted me for that other person. Because each of us can identify with how devastating it is to lose the object of one's love, especially in the context of a long partnership or marriage, we tend to be less shocked when we hear that jealousy was the motive for a murder. We also realize that a loss in a love relationship is harder to replace than loss of a job. This makes us more sympathetic in the case of a jealousy murder (especially if the killer found a spouse in bed with a lover) than with a workplace murder where the killer shot the boss after being fired. The word evil is not so often used when commenting about a jealousy murder, unless the circumstances are extraordinary. Two examples might be: the victim had in reality done nothing to evoke jealousy,3 or the victim had indeed cheated on the killer—who nevertheless resorted to extremes of mutilation or torture in exacting “revenge.” Absent this kind of excess, jealousy murders seem the least evil and fit into the lowest categories of the Gradations of Evil scale: Category 2, or perhaps a little higher.

There are other types of spontaneous, or “expressive” violence and murder unrelated to jealousy: violence during a brawl or in the course of an argument. Family fights that end in murder belong in this category; we shall see a few such examples in chapter 8. Murders of this type seem more avoidable and often enough closer to what we mean by evil. Many of the spur-of-the-moment murders and other acts of violence committed by people with severe mental illness fall under this expressive heading and are sometimes so spectacular as to smack of evil—until we learn that the person in question was acting under the command of imaginary voices or something similar. This was the case with the young man who threw his father's head out the window—or with another mentally ill person who slit open her mother's abdomen in the belief that the mother's exterior was the devil and that the “good” mother was inside, waiting to be released.

When things go very wrong in the sphere of work, we may find a different set of responses, and different motives for criminal acts. Greed is a common motive, as in arson carried out in the expectation of getting the insurance money, as well as in the more mundane crimes of theft, burglary, and robbery. The motives behind certain work-related murders are to get rid of a business rival or to avenge a real or fancied wrong—of which retaliation for being fired is a common example. Schoolwork is work, too, in the broader sense of the word; many of the mass murders committed on campus are in retaliation for being dismissed from high school or college for failed grades. Mass murders are almost universally regarded as evil no matter the motive (which is almost always revenge), and no matter if mental illness is a factor—given the enormous amount of destruction and loss of innocent life occurring in the wake of such crimes.4 In all but the rarest of cases, these murders are instrumental.

Before we flesh out the theme of jealousy with actual examples, it should be recognized that both an expressive and an instrumental motive may get compressed together in one violent episode. This may happen when someone else's action ignites an overwhelming rage, sparked usually by an intolerable feeling of humiliation and a consuming hunger for revenge (the “expressive,” heat-of-passion component). This is quickly followed by a methodical plan to undo the humiliation by a violent act (short of or including murder) that will then “even the score” and restore the person's sense of self-worth. The accomplished forensic psychologist Reid Meloy has written about this reaction, and the crimes that occur in the aftermath, under the heading of catathymic crisis.5 There is a close connection between this violence-inducing crisis and what Jack Katz had spoken about under the heading of “righteous slaughter.”6

JEALOUSY—WHERE ITS POWER COMES FROM

An Evolutionary Look

Jealousy is best understood as the extreme of an emotional state for which our brains are wired to safeguard what is most precious to us: a sexual mate by whom we hope to have children who will carry our genes (half of them, anyway) into the next generation. For most of us, this is our best hope of immortality. A few geniuses can manage immortality of a different kind without children—like Michelangelo or Beethoven or Schubert. Most of us, however, rely on our children. Our brain has not changed appreciably from the days long back in the African savannah from which we began to spread out some fifty thousand years ago. In that setting, survival of the group and of the individuals within the group was dependent upon division of labor between the sexes. Women bore children and nurtured them. Men safeguarded the perimeter and hunted and gathered for food supplies to guarantee the group's survival.7 It has been important for men to have assurances that the children they are working to support are truly their own. For women it has been important to have assurances that their mates will be loyal and devoted to them during the vulnerable period when their children are small and need maximal care and protection. Jealousy relates to the resentment stirred up if a man loses his sexual partner and if he is forced to worry that the children he has been working to support really belonged to some other man. For the woman, she, too, will feel threatened if she loses her sexual partner, but she will feel especially threatened if she is abandoned and left without the vital support she needs when her children are young and helpless. It is an elementary fact that women at least know that the children they bear are indeed their own. Fatherhood is a dicey business—for which reason men go to great lengths to ensure that they are truly the fathers of the children born to their mates. Until DNA testing became available the mid-1980s to resolve paternity disputes, just about the only men who could be completely certain of their paternity were the Ottoman sultans.8 Each sultan had a harem (the word means “forbidden”) safeguarded by eunuchs (of a different race than that of the sultan, to further guard against cheating). Girls were brought into the gilded prison of the harem before puberty, to be “harvested” when they reached childbearing age by the sultan and only the sultan. Other men have had to make do with long engagements, preceded by the careful guarding of a girl's chastity via the vigilance of her father and brothers. Marriages in many cultures were arranged. Prior “dating” was unheard of; virginity of the bride was demanded. Sexual cheating by a spouse, that is, adultery, was punished with great severity or even by death. Socially we've come a long ways. But our brains, having evolved to ensure the continuity of our treasured genes, are still prone to react with violence when faced with the fact—or even the hint—of sexual betrayal. There are still many parts of the world where killing a mate caught in bed with another sexual partner is not even considered a crime. Sometimes, even killing when there is no more than a suspicion of infidelity may be tolerated as a “justified homicide.” When I was in Bogotá, Colombia, many years ago, I read on page 7 of the local paper a two-inch column describing how a judge shot his wife to death at a cocktail party when he saw her “looking at another man” (hard for a wife to avoid when she is hostess at a large party). In that locale the incident was not a crime, nor was the judge reprimanded.

There are still other reasons why either the fact or the worry about sexual betrayal may make jealousy rise to such a fever pitch. One's chances of finding a replacement for an abandoning mate may be drastically lowered because of one's (advanced) age, disadvantaged social position, or unattractiveness of physique, personality, and behavior. To be young, high in social rank, well to do, good looking, and pleasing in personality is to be less vulnerable (usually) to feeling murderous jealousy. There are exceptions, however. If a person occupies high public office or a prominent social position, betrayal may cause such loss of face, such public humiliation that drastic action (including the murder of the deserting mate) may seem, to the victim at least, the only acceptable solution. This was the situation with Shakespeare's Othello. As a Venetian general and governor of Cyprus, he could easily have found another woman to marry, once he thought Desdemona had cheated on him with Cassio. Of course the audience knows that Desdemona has done no such thing, and that it was the evil, scheming Iago who planted the seed of jealousy in his hated superior. But in the culture of that place and time, and because of his public visibility, Othello could not shrug off being cuckolded with calm and grace. To save face, Othello kills his wife. We see this as murder. Othello would see his act as the simple administration of summary justice—until, that is, Desdemona's handmaiden makes Othello aware of Iago's treachery. Now faced with having murdered, rather than “rightfully killed,” his wife because of his baseless suspicions, Othello commits suicide.

The power of Shakespeare's play stems in no small part from the plot's similarity to what happens all too often in real life and is based on feelings with which almost all of us have one time or another struggled. In Verdi's opera Othello we see the instantaneous switch from burning love to burning anger. We sense the fatal consequences that jealousy will swiftly bring in its train. The very adjective we use—“burning”—describes perfectly the powerful impulses here: the consuming urge to make love and the explosive urge to kill, separated only by a razor-thin partition in the jealous soul.

We should not overlook yet another factor that can raise jealousy to the point of murder. This is the phenomenon sometimes spoken of as a grand passion, sometimes as an obsessive love. It is more a characteristic of the young—who may fall in love with such intensity (as in Romeo and Juliet) that no other person on earth could ever satisfy as a replacement for the beloved.9 This kind of love harkens back to the uniqueness of the bond between mother and infant in its earliest days—for whom, after all, mother is the only irreplaceable figure. But whatever its psychological underpinnings, this kind of all-consuming (and to that extent, morbid) love can readily inspire the urge toward murder and suicide, should the beloved suddenly desert one for another. One is reminded of the Spanish saying: el raton que no sabe mas de un agujero, el gato lo coge presto—the mouse that only knows one hole, the cat catches quickly. This is the situation with the person who knows one and only one option, one solution, to the quest for a mate. When one loses their beloved—especially if the beloved has rejected one for another—life loses all meaning. Reduced to one option, there is only death, and whether that occurs by suicide, murder, or murder-suicide is a mere detail. The technicality of interest here is that because two of the choices involve murder, the issue of evil is evoked.

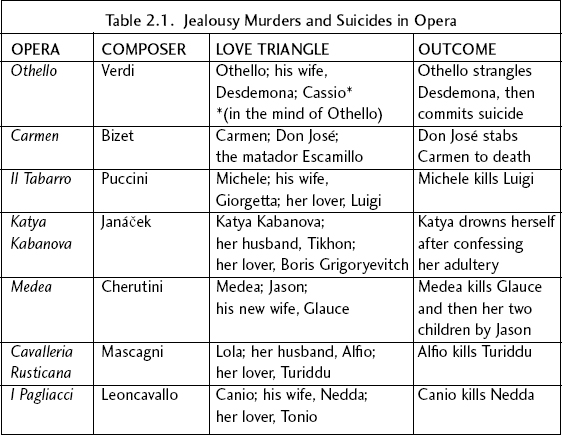

There are many examples of jealousy murder to be found in the crime literature, to say nothing of the less-prominent cases in magazines and daily newspapers. These cases have a way of touching us, because they can so easily stimulate the thought that there but for the grace of God go I. Our susceptibility to jealousy is a quality shared by all peoples from all cultures—and this is why we find it so often the major theme of operas, plays, and novels. The table below shows the details from just seven among the hundreds of operas built around jealousy.

We can speak of a biological push in the direction of jealousy, when we view this emotion as an early-warning device that evolution steered us to by way of minimizing the tendency to cheat. As a species, we are inclined—men probably more so than women—to a certain measure of sexual promiscuity. The poet Dorothy Parker10 understood this as well as any evolutionary psychologist, when she penned her famous quatrain:

Higgimus hoggamus

Women—monogamous;

Hoggamus higgamus

Men are polygamous.

Chimpanzees—our closest primate cousins—are notably more promiscuous than humans;11 geese and prairie voles (small mouselike creatures), in contrast, mate for life. We occupy a position in between, perhaps nearer to the geese and voles. Chimpanzees would think operas about jealousy were crazy; prairie voles wouldn't understand what they were all about. Most human cultures encourage us strongly to mate for life, which for many will create a conflict between what we ought to do and what we might like to do. The rules we are supposed to live by were given to us long ago: the Old Testament tells us “Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor's wife nor his maidservant.”12 Those who recite the Lord's Prayer ask of him: “Lead us not into temptation.”13

JEALOUSY MURDERS

The jealousy murders described in this section are of the expressive, or heat-of-passion type, driven by sudden impulse and showing little or no planning. What planning was involved, if any, had mostly to do with hiding evidence so as to escape being brought to justice.

George Skiadopoulos

The story concerns a wild and beautiful “pin-up” girl, Julie Scully, who had modeled for magazines and then married a wealthy businessman, Tim Nist. Men found Julie “foxy,” but she was also very bright and had a fabulous memory. Still, she abused drugs, had a theatrical temperament, and was one of those people whose engine required novelty and thrills to keep it running. She became bored with her husband after a few years, and while on a cruise in the Caribbean, she met a younger Greek sailor, George Skiadopoulos, with whom she quickly fell in love. Soon after, Julie and Tim divorced. Julie began to live with George. An intensely jealous man, George would listen in on her phone calls and became argumentative—even with Julie's mother, whom he once tried to choke. Tim, who was still in Julie's life because of their daughter, advised Julie's mother to press charges. As a result George was made to return to Greece, where he implored Julie to join him. This she did, but she found the little town where George lived wearying and dull. She insisted on returning to the United States to see her daughter, realizing that she no longer loved George anyway. At this point George lured her to a remote spot, strangled her to death, and dismembered her, throwing her body parts into the Aegean Sea. Police saw through his claim that she just “went missing,” and he was sentenced to life in prison without parole. The dramatic nature of the murder gives it the ring of evil, though Skiadopoulos's flaws were those of jealousy, anger, and impulsiveness—plus, in linking his fate to Julie, he had tackled more than he could handle. I placed him in Category 2 on my scale. His story resonates remarkably with that of Carmen, the seductive gypsy so similar to his Julie, whom George, as the counterpart of Don José, killed the moment she flung him aside.14

Clara Harris

The only child of an affluent Colombian family, Clara Suarez Harris became a dentist and married another dentist, David Harris. They lived and flourished in an upscale enclave in Houston, Texas. Childless for several years, Clara eventually had twins. A tall, attractive woman, she got busier than ever with motherhood and her practice. David felt sidelined and entered into an affair with his receptionist, Gail Bridges. They were not very discreet, and word got out to Clara. Thanks to a private investigator, Clara discovered that David and Gail had checked into a hotel. She drove there, and when she saw the two emerge from the hotel, she revved up her car and drove into her husband, running over him three times, killing him. Like other jealousy murders where someone suddenly “snaps,” Clara Harris is not so different from Jean Harris (no relation to Clara) who murdered Dr. Tarnower, or George Skiadopoulos. But there was a modest degree of intentionality in her act (driving to where she assumed he and the other woman would be and thus putting herself into a state of higher emotion and risk for violence). Also, there was a measure of “overkill”: backing up her car in order to run him over two more times as he lay on the road.15 Taking these aspects into consideration, I placed her in Category 6.

Jeremy Akers

Born in Mississippi to a working-class family, Jeremy Akers was a straight-A student, a bodybuilder, and a highly competitive man. Self-conscious about his height, he became an “overachiever”—working twice as hard as necessary to achieve his potential. He graduated law school and served in Vietnam, winning several medals. Upon his return he married Nancy Richards, who came from a wealthy family in the northeast. Her parents were against the marriage because of his abrasive, hot-tempered behavior. Macho to the point almost of caricature, Akers was brash, domineering, and opinionated, but also jealous and possessive. The marriage began to deteriorate. Nancy was depressed after the birth of her third child and she gained a great deal of weight. Her husband grew critical and disparaging, even though she managed to get back down to her original weight and underwent some cosmetic surgery. Ever more dissatisfied in her marriage, she struck up an acquaintance with a truck driver, Jim Lemke, twenty years her junior. Love of writing formed part of their bond: he wrote poetry, Nancy wrote novels. They became lovers, and for a time Jim even lived in the Akers's own home, as though he were just a “friend.” Jeremy suspected Nancy's infidelity despite Jim's denial of it, and his already jealous feelings escalated when Nancy sued for divorce. Jeremy begged her to reconcile, but she refused and went to live elsewhere with Jim—despite Jeremy's warning that he would kill her rather than submit to divorce. Finally, after luring Nancy back to their house under the pretext of discussing divorce details, Jeremy shot her to death with a .38, which he then turned on himself, committing suicide a few hours later.16 Here is another example of an “evil” act by someone no one considered evil (nasty, maybe, but not evil). Pride and jealousy contributed to his conviction that there was “no other option” but murder—the “righteous slaughter” of which Professor Katz wrote. Besides Jeremy's intense egotism, there was careful planning here, as well as deceit (tricking Nancy to return to their house), making this case appropriate for Category 7 of the scale.

Jonathan Nyce

The eldest of four boys from a working-class family in Pennsylvania, Jonathan Nyce was studious, quiet, awkward, and lacked confidence around girls. He suffered no abuse or losses during his formative years. An excellent student, he eventually earned a doctorate in molecular biology. As an asthmatic himself, he turned his efforts to asthma research. His first marriage failed after seven years. He then began corresponding with a Filipino girl, Mechily Riviera, and eventually flew to Manila to meet her and propose marriage—which she accepted. At forty, he was twice her age, but he pretended to be thirty-two. In the early 1990s they had two children, and Jeremy founded a company for producing what he hoped would be an asthma cure. He obtained considerable venture capital, and they moved to a huge house, living in luxurious circumstances. The business began to fail, however, especially when venture capital dried up after 9/11. Even so, Jonathan installed a gym inside their house because he worried that Mechily would attract other men if she went to the local gym. She was, after all, very attractive. But the real problem resided in his behavior toward her. He limited her freedom as though she were a harem concubine; to make matters worse, she found out he had lied about his age. And money problems aggravated the situation.

In these unsettled circumstances, Mechily developed an attraction for the landscape gardener she had hired. Again she ended up with a man who lied to her, only this time, the lie concerned his name. She knew him only by one of his aliases, “Enyo,” though his real name was Miguel DeJesus. Jonathan—already depressed because he was voted out of the directorship of his company—suspected Mechily was cheating on him. This was confirmed by a private investigator. One night, when Mechily came home late after having been with Miguel, Jonathan smashed her skull with a baseball bat. Placing her body into the driver's seat of his car, he then pushed the car down an embankment, and told the police that her death resulted from an accident. When the real cause was discovered, he was arrested and then convicted—though the judge was unusually lenient, sentencing him to only five years for “passion/manslaughter.” He continues to deny having killed his wife. The murder was impulsive but was followed by “staging” of the crime scene—to fool the police and to escape arrest: an “expressive” act followed by an “instrumental” act. Still, Dr. Nyce, though jealous and narcissistic, was not psychopathic.17 The case fits in Category 8 of the scale.

IMPULSE MURDERS OF OTHER TYPES: EMPHASIS ON RAGE

Murders done on the spur of the moment do not all derive from jealousy. The driving force can be rage that is ignited in a few seconds, or it can be a smoldering anger that gradually builds up and crosses the threshold into murderous rage. The following murder was done in a state of what is called “blind rage”—a state in which all semblance of rationality and self-control is momentarily lost. It is as if someone were driving a car without brakes, the accelerator pedal to the floorboard, and with a blindfold firmly in place. The trigger can be an overpowering humiliation or else a feeling of entrapment in an intolerable life situation. Most of the people in these situations have no psychopathic traits. But as we ascend to the higher categories on the scale, we see some extreme egocentricity along with a few psychopathic traits (such as callousness or a lack of remorse). We are dealing with evil acts—committed by people whom others would rarely call “evil” in any general, day-in day-out way. As we shall see, in some of the cases, rage led to repeated stabbing with mutilation of the body or to destruction of the body through burning. As we try to imagine what the victims must have felt in such circumstances, the notion of “evil” comes more quickly to mind than if the murders were (relatively) painless, say, from a stab to the heart or a shot to the temple.

Susan Cummings

One of fraternal twin daughters born to a billionaire arms dealer and his Swiss wife, Susan Cummings lived on a huge rural estate in Virginia where she owned and managed a horse farm. Whereas her sister was pretty and popular, Susan seldom dated and was shy, tomboyish, and not as attractive. She fell in love with an Argentine polo expert, Roberto Villegas, hired originally to teach her how to play. He had come from a poor background but now moved among the people in Virginia's well-to-do “horsey set.” In 1995 they moved in together, but the “honeymoon period” was short-lived. Each became increasingly irritated with the other. Roberto was ill-tempered and verbally abusive. Rumor had it that he was also cheating on Susan. She became sexually indifferent and tended to alienate him as well as others by her tightness with money. Local farmers would complain, for example, that she haggled over a $5,000 horse, offering only $500, despite being immensely rich. By 1997, the situation between the two became explosive, culminating in Susan shooting Roberto to death (with four bullets) in her kitchen. Her upbringing with her arms-dealer father had made her quite handy with her 9mm Walther semiautomatic. Claiming she had acted in self-defense, she showed some cuts on her body and produced a knife when apprehended. Some thought she had done the cutting herself to make her reaction seem more justified. Though declared guilty of manslaughter at the trial, she was sentenced to a mere sixty days in jail.18 Hers is not the story of an inoffensive woman maltreated by a bitter and vindictive brute, the way Heathcliff treated Cathy's daughter in Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights.19 Roberto was no ideal mate, but Susan contributed in good measure to the tension that finally precipitated the murder. For this reason I felt her story conformed to that of Category 4 of the scale: killing in self-defense, but extremely provocative toward the victim.

Robert Rowe

Robert Rowe was an attorney, one of two brothers raised in a Protestant family. He married a Catholic woman, Mary, over the stringent objections of his bigoted mother. They had two sons: Bobby, the normal one, and Chris, who was born blind and deaf, owing to Mary's having contracted rubella early in that pregnancy. Robert proved unusually stoical in the face of so handicapped a child. He formed a support group for other similarly affected couples, who took inspiration from his cheerfulness and self-transcendence. When he was forty, he and Mary adopted a girl, Jenny. Rowe's mother died three years later, but not before humiliating him with her “confession” that she wished she could have aborted him as she had done with her first two pregnancies. Added to that, she told him she saw him as just a lowly bureaucrat, a fake, and the head of a damaged household. As her final coup, she disinherited him, leaving what little she had to his brother, Kenny. Robert had several disturbing dreams in which his mother urged him to kill his whole family. He became seriously depressed, began to hear voices, and once fled the house after he had started to pick up a kitchen knife.

Under the care of a psychiatrist, he was given medications for depression and anxiety. No longer able to work as an attorney, he took a job as a cab driver in New York. Through his carelessness, his cab was stolen, so the $25,000 he spent for the taxi medallion was lost. Reduced to being a house husband while Mary worked, he sunk deeper into depression, and deeper still when he learned that Bobby, his “normal” son, had a congenital hip disease that might consign him to a wheelchair. Robert stopped taking his medication, causing him to plunge to the very bottom of depression and despair. He thought of placing Chris in an institution, but Mary wouldn't hear of it. It was this endlessly deteriorating situation that culminated in February of 1978 with his taking a baseball bat and crushing to death his three children. When Mary came home, he put a blindfold on her, telling her he had a “big surprise” for her—the surprise was killing her with the bat as well. Rowe then made a suicide attempt with gas from the oven but was rescued by a neighbor who summoned help. He confessed to the murder of his family and was sent to a forensic hospital.

Released three years later, he was able to gradually rebuild his life. He remarried and had a son. Rowe died five years later at age sixty-eight. His is the story of murder under tragic circumstances, remorse, and redemption. Though he had been temporarily in the grips of a psychotic depression20 (one in which he heard voices), Rowe had no psychopathic characteristics. His case corresponds to Category 5 on the scale: desperate persons who have killed (usually relatives) but who are without psychopathic traits. What made the murder appear more “evil” was the public's reaction to the bludgeoning of one's whole family with a blunt instrument. There was also some premeditation—in the blindfolding of his wife so that she would have no idea what he had in store for her.21

Susan Wright

As a young and pretty woman of eighteen, Susan Wyche had worked for a time as a go-go dancer. Jeff Wright, who had met her at the discotheque where she worked, became enamored of her. In the stormy affair that ensued, she became pregnant, but to her irritation Jeff put off marrying her till she was eight months along. Jeff was a fairly successful salesman, so they were able to live in a pleasant area of Houston, Texas. But Jeff was addicted to cocaine and to other women. These avocations were ruinous to their finances. Susan caught a sexually transmitted disease as a result of one of his escapades. She also complained that he was physically abusive, partly because, infidelity aside, he was very jealous of her. The abuse history was corroborated by her mother and denied by his mother.

In January of 2003 Susan's anger reached the boiling point. One evening she enticed Jeff with the promise of sex into a bondage game in which he let himself be tied to the four corners of the bed. In a paroxysm of rage, Susan then sliced at his penis and stabbed him almost two hundred times all over his body. Becoming panicky, she then dragged his body to their backyard where Jeff had for some reason dug a pit. She placed his body there, thinking to tell people he had “disappeared.” Their dog dug up the body a few days later. At the trial that took place after her arrest, the prosecution argued that she killed him for insurance money, but this was far-fetched. If the burial had been successful, Jeff would not have been declared officially dead for seven years. The defense argued that she was a battered woman who had “lost it” in a fit of rage but had to resort to trickery because he was twice her size and much stronger. Some courts, recognizing the “unfair fight” element when a large man is abusive to a small woman, show leniency; others do not. Susan was given a twenty-five-year sentence with the possibility of release in half that time. She was not psychopathic. The case has the features of an impulse murder, but some planning was evident just before and just after the attack as a result of her physical weakness compared to her husband's size and strength.22 Category 5 seems the appropriate level for Susan Wright.

Ed Gingerich

Married to an Old Order Amish wife from the Pennsylvania Amish community, Ed Gingerich was befriended by an evangelical Christian man, David Lindsey, from the surrounding non-Amish population. David hoped to proselytize Ed, who in the process began to feel torn between the two ways of life. Ed had ambitions to be more “free,” like the “English”—as he called the non-Amish people, yet he felt strong ties to the Amish ways, which included avoidance of cars, telephones, electricity, and doctors from the outside. In this context Ed suffered a nervous breakdown and began to have visions and dreams about leaving the old religion. He was sometimes abusive to his wife, Katie. Though the breakdown led at first to Ed's going to a conventional hospital, his wife and brother persuaded him to stop taking the medications the doctors there had given him. Instead they insisted he see an Amish chiropractor and healer who prescribed molasses for his condition (as the healer did for all other conditions as well). Ed's paranoid preoccupations with visions and the devil quickly resumed. He became combative at times or would crawl on the floor sobbing. In 1993 Ed had wanted to attend a wedding, but Katie insisted he go instead to an herbalist far away.

That man was honest enough to say he could offer nothing of help, urging that Ed be hospitalized instead. The family refused, forcing him to see the molasses doctor instead. The actual day of the wedding, Ed became enraged and beat Katie to death with his fists, tore her abdominal organs out in front of his children, and smashed her skull. At trial he was called “guilty of involuntary manslaughter, but mentally ill,” and was sent to a forensic hospital unit in a Pennsylvania prison, where he spent about two years. It was discovered that when Ed was about ten, he had fallen off a horse and was unconscious for a time; this may have played some role in his eventual breakdown. Some people in his community still consider him an unstable and potentially violent man.23 The Gingerich case conforms to Category 6*: impetuous, hotheaded murderers, yet without psychopathic features. I add an asterisk here to draw attention to the presence of mental illness. In the last section of this chapter, I will have more to say about the way certain crimes committed by the mentally ill elicit from us the reaction: evil! more predictably than do the crimes of others.

Dr. Bruce Rowan

The youngest in a large Idaho family, Bruce Rowan had been depressed most of his life, grappling with suicidal feelings and convictions of being “unworthy.” His depression continued through his medical school days, in the middle of which he was hospitalized briefly because of suicidal thoughts. At one point he made a suicide attempt with pills. He had a girlfriend, Debbie, who stood by him, partly out of love, partly out of fear that if she were to leave him he would kill himself. They married, and for a while they went around the world doing charitable work among the poor in various countries. Once back in the United States they adopted a baby girl. His wife wanted to get a house and settle down. Bruce was still eager to roam the world, his lofty ambition—to help the poor—being driven in part by the hope this would alleviate his chronic feelings of unworthiness. Debbie of course spent considerable time with the baby. Bruce grew increasingly resentful at having to do chores around the house and at having less “quality time” with his wife.

In March of 1998 his resentment crossed a threshold into rage, and he killed Debbie with an axe. He then put her body into their car, pushing it down a hill to make it appear as an accident. Afterward he stabbed himself in the abdomen, using his medical knowledge to avoid spots that might prove fatal. All this happened the day a half-million-dollar insurance policy he had taken out for Debbie (for which he was beneficiary) had come due. At trial Dr. Rowan was declared not guilty by reason of mental illness and was sent to a forensic hospital. His long-standing depression outweighed, in effect, the planning that accompanied what was otherwise primarily an impulse murder born of rage. The lenient decision was in all likelihood a reflection of his being, in general, neither psychopathic nor sadistic, despite his extreme egocentricity.24 The Rowan case fits into Category 7 on the scale: highly narcissistic but not distinctly psychopathic persons, often with a psychotic core, who kill loved ones or family members. Killing his wife with an axe, even factoring out the “staging” of the murder to resemble an accident and the insurance windfall, was enough to earn the label of “evil” from the public, even more so because the killer was a physician who once had taken the Hippocratic Oath: Do No Harm.

Gang Lu

One of four children from a middle-class family in mainland China, Gang was an outstanding student. This enabled him to attend an American university for graduate studies in physics. Enrolled at the University of Iowa, he earned his doctorate, but he had hoped to get a certain physics prize as well. He was barely beaten out for the prize by another Chinese student, Lin-hua Shan. Gang became progressively embittered and paranoid, insisting that the heads of the physics department had been conspiring against him to deny him the prize. In the fall of 1991, twenty-eight-year-old Gang obtained a pistol permit, not a difficult accomplishment in this country for someone with a “clean record.” Then in November, Gang calmly shot to death the chairman of the physics department, a professor who had sat in when Gang defended his PhD thesis, yet another professor who was his mentor, a female dean who Gang regarded as “dismissive” of his (frankly paranoid) letters of appeal, and last but not least, his archrival, Lin-Hua Shan. He then committed suicide.

People who knew him on campus described his personality as a collection of the following traits: combative, argumentative, envious, bitter, difficult to live with, shy, a “loner,” quiet, brooding, resentful, slovenly, “know-it-all,” self-centered, nit-picking, abrasive, rigid, aloof, critical, hotheaded, a “spoil-sport,” overly proud, and paranoid. A devotee of pornographic and violent films, Gang was narcissistic and possibly personally repellent, but he was not psychopathic. This configuration is very common in persons committing mass murder—a topic I will expand upon later. We know less about the personal lives of mass murderers than we do about most other types of murderers, because they usually die at the time of the murders, either by their own hand or by the police. The appropriate category for Gang Lu would be 8: non-psychopathic murderers with smoldering rage, who kill when the rage is ignited. The general sentiment surrounding this case; namely, that an evil had been committed, reflected both the enormity of the crime—five lives lost—and the fact that the victims were all highly placed and highly valued members of the academic community.25

IMPULSE MURDERS AMONG THE MENTALLY ILL

In commenting on murderous or other violent acts by mentally ill persons—acts that reach the level of “evil” in the public's opinion—our first task is to try to take the vagueness out of the inherently vague phrase “mentally ill.” People in ordinary life are inclined to call anyone “crazy” or “mentally ill” who commits a violent act of particular gruesomeness, especially if it is unprovoked. Someone who castrates a man and then eats the genitals or other body parts will unfailingly be called “crazy” not only by the public and by journalists covering the story, but also by most judges who might preside at the subsequent trial. But this is because the act was so repugnant and primitive, nauseating, even, and so rare, that it goes beyond the imagination of most people to think such a person could be “sane.” Sane, however, is no longer a psychiatric term so much as a legal term, indicating that the person in question knew right from wrong and understood the nature of his act.26 Most mentally ill people are not so far out of touch with reality as to lose those distinctions, so legal insanity is rare indeed. For our purposes, we will restrict the phrase mentally ill just to those persons who suffer from a condition that, for some extended period, causes them to be in poor contact with reality and to suffer certain symptoms such as delusions, hallucinations, and peculiarities of speech—as seen commonly in schizophrenics or people with a mood disorder so profound as to cause the rapid-fire speech and grandiose ideas typical of the manic person. The extreme self-disparaging thoughts of the seriously depressed or melancholic person would be another type of mental illness, as we saw with Robert Rowe and Dr. Rowan in the examples above. In some mentally ill people, both thought and mood are morbidly affected.

I recall a particular case as an example. A woman had been in a psychiatric hospital shortly after her husband divorced her. Now at home, she fell into a deep depression, but she also came to believe that her ex-husband, who lived miles away, was sending poisonous rays from his eyes that went through her windows and made her ill. Another example: a man took his rifle and shot his neighbor, convinced that God had commanded him to kill “Satan” (the neighbor having, in his mind, somehow morphed into the devil) so that the world could be “saved.” Every so often one will hear of a mentally ill man who stabs his pregnant fiancée or wife to death, believing that God, or perhaps some secret terrorist organization, has ordered that the woman die because she is “really” the whore of Babylon or else the enemy of the state, who must be killed so as not to bring destruction upon the world. These are all examples of mental illness. Although the bulk of mentally ill people, defined in this way, suffer from schizophrenia (which primarily affects thought processes) or manic-depression (which primarily affects mood), some will develop conditions with similar symptoms that result from serious head injury or from abusing drugs such as methamphetamine, cocaine, LSD, or alcohol. Extremely heavy, repeated use of marijuana can induce mental illness of this sort as well. All these conditions come under the heading of “psychosis,” which is simply a technical term indicating a condition that seriously disturbs one's grip on reality. When a psychosis is connected with a chronic condition such as schizophrenia, the more serious forms of mood disorder, or head injury, we are on more certain ground in speaking of mental illness. The situation becomes more murky and controversial in many cases of drug abuse, because of the seemingly voluntary nature of the abuse. One could presumably have chosen not to get drunk and therefore chosen not to have committed whatever act of violence the alcohol “made” him do (as the offender might try to argue in court). Public opinion is divided on this point. There was a young man from North Carolina, some years ago, for example, who got drunk, and while inebriated shot his rifle through his car window as he was driving, killing a passenger in a car that had been driving alongside his. In court, the shooter was called by his attorney “temporarily mentally ill because of the alcohol” and thus not capable of exercising judgment as to right or wrong—hence not responsible. Surprisingly (surprising to me, anyway) the judge accepted this interpretation and sent the man to some treatment program rather than to prison. In my view, the man had effectively willed himself into a state of lowered self-control, where he was more at risk to do something foolish and dangerous—and was therefore doubly guilty and doubly dangerous.

But if we now turn our attention to the unequivocally and chronically mentally ill, controversy and disagreement will evaporate. It turns out that some of the most horrifying and repellent acts of violence, where the word evil comes immediately to almost everyone's mind, are committed by mentally ill—especially schizophrenic—people. Those laboring under bizarre delusions or who have succumbed to psychotic rage may act as though freed from all inhibition, or as though the victims they are attacking or mutilating are not really “people” at all. All restraints are off; no “punishment” is too great. And when a psychotic person commits mayhem in this way, through dismemberment, cannibalism, mutilating disfigurement, and the like—the scene will be splashed on the front page of the tabloids as a combined titillation and warning about what shocking things crazy people are capable of. And herein lies a problem of immense consequence to the general public. In the minds of many people, events that make headlines appear to be precisely the kinds of events that “happen all the time” against which we must be perennially on guard. Yet the hard facts and the statistics tell a different story—one that has great meaning for our discussion of mental illness, evil, and the supposed overlap between the two. Apart from the crimes of serial killers and mass murderers (most of whom are disgruntled loners but not necessarily psychotic), it so happens that the term evil is applied with particular frequency to certain acts of violence by the mentally ill. We saw this in two of the examples above: the schizophrenic man, Ed Gingerich, and the psychotically depressed man, Dr. Rowe. But if we looked at our entire population, what would we see?

In the whole population of America, there were about 20,000 murders in a year during the 1992–1998 period. This decreased to approximately 17,000 in 2003.27 If one looks at the larger number of victims of violent crime in that year (since most victims survived), 480,000—one in five—needed care in an emergency room or in a hospital. The offenders were usually an intimate partner (48 percent) or family member (32 percent), and less often a stranger (20 percent). Firearms were the instruments behind most of the murders (72 percent) in the United States. Most of the killers were male (90 percent) as were the victims (77 percent). The murder rate per 100,000 persons dropped from about ten (1972–1994) to five and a half or six in recent years. Whereas most murderers in Sweden had a record of mental illness (90 percent), the figure is very low in the United States owing largely to the much easier access to guns in this country such that many mentally fit people can easily obtain pistols or rifles. The best recent estimates for the number of homicides committed by those with “severe persistent mental illness” in the United States suggest a figure of about 1,000 per year. Compared with the figure of 17,000 in the year 1998, this would mean approximately 6 percent of the murders were committed by the severely mentally ill. This number is misleading, however, because the mentally ill without substance abuse account for barely 3 percent of the murders; those who abuse alcohol or other drugs may account for 9 percent to even 15 percent.28 In Britain as well, one is much more likely to be killed by an alcoholic than by a “crazy person.”29

Another important figure to keep in mind is that the rate of violence (including the much larger number of minor to moderate injuries, not just the rare murders) among the mentally ill (among schizophrenic and manic-depressive persons, for example) is about 3 to 5 percent.30 Of one hundred mentally ill people, if followed for several years after release from a hospitalization in the United States, three to five will have engaged in a violent act—meaning that ninety-five to ninety-seven will not have done so. This should be reassuring to the public, who may fear the risk posed by the mentally ill.31 But it is not. Why? To begin with, most acts of violence by the mentally ill are done on impulse, lending them a disturbingly unpredictable, and thus more frightening, quality. Secondly, their violent acts, rare though they be, all too often are not only unpredictable but unnerving and spectacular. And the headlines will often contain the word evil. It is not easy to avoid sensationalism in describing these headline-grabbing cases. The examples I am about to relate I have accordingly toned down as much as I can without obscuring the nature of the violent acts altogether.

In a case that earned national attention, a schizophrenic man, Andrew Goldstein, pushed a woman, Kendra Webdale, off a New York City subway platform into the path of an oncoming train, killing her. He had lived for a time in a supervised residential setting where he took his prescribed antipsychotic medications, but after a time he chose to live on his own. From that point on he stopped taking his medications and relapsed, experiencing delusions and hallucinations, and engaging in unprovoked aggressive behaviors. There were many emergency-room visits and a “revolving-door” situation where he would spend a little time in the supervised residence and then leave of his own accord, always neglecting to take his medications when on his own, and always spiraling down into active psychosis as a result. The death of the woman he pushed later spurred legislators to enact “Kendra's Law,” authorizing long-term assisted outpatient treatment for patients with severe mental illness.32 The program, where implemented, has had good success in reducing (though by no means eliminating) the frequency of harmful behaviors.33

In a news item from Seattle in March of 2007: “a mentally troubled woman accused of drowning her six-year-old daughter, cutting off her head and throwing the remains off a bridge, has pleaded guilty to first-degree murder.”34

A schizophrenic man in his forties, with a long record of being abusive toward his mother—physically attacking her on a number of occasions—had been in and out of mental institutions many times. In a similar pattern to Andrew Goldstein's case, above, he would be released, would stop taking his medications, and would then experience a relapse. In his psychotic state, he imagined the FBI was following him and that he could save the world by getting people to give up their money and credit cards, since without them, “there would be no war or crime.” He would walk around the city looking for the rainbow or else feeling he had turned into a bear. Finally, he began to believe his mother was “Satan,” and in that state of mind, he attacked her with a knife, stabbing her many times and cutting out both her eyes—with the rationale that “now the World could see again.” He felt compelled to attack his mother in this way so as to satisfy terrifying hallucinatory voices, as if from God, commanding that he “kill Satan.” Shortly before the fatal attack he had complained in a hospital emergency room that radioactive emissions from a satellite were entering his brain and bothering him, making him feel that his own life was in danger. The murder was characterized as an evil act by the media immediately thereafter, but public reaction softened when it became apparent that the man was severely psychotic. Neighbors testified that when he was taking his medication, he was polite and friendly and helpful toward his mother, with whom he lived during his adult years when not in hospital.

A man in his late twenties had recently become a father. The burdens of the new responsibilities and demands that accompany fatherhood—being able to relate lovingly to the infant, working consistently so as to support the growing family, accepting the necessary shift of attention on the part of his wife toward the new baby—pushed this fragile man beyond his coping capacity. Already struggling with depression before he married, he now fell into a psychotic depression. Hearing God's voice urging him to destroy both himself and the infant so as to save the world from even bigger destruction, he jumped out the window, clutching his six-month-old son. He survived; the infant did not. The man was then sent by the courts to a forensic hospital.

Though marijuana is not often implicated in crimes of the “heinous” or “depraved” sort that would place them in the realm of “evil,” heavy use in vulnerable persons may result in violent acts. A gifted young artist, for example, began to abuse marijuana several times a day every day in a deteriorating family context, one aspect of which was his mother having become extremely seductive toward him after the death of his father. As his tension mounted and his self-control weakened under the influence of the cannabis, he one day “lost it,” and on impulse bludgeoned his mother to death. While smoking the marijuana so heavily, he began to show psychotic symptoms: delusions that his mother was the devil and that it was his mission to kill her. He has now spent many years off marijuana and on appropriate medication in a forensic hospital, where he has made an excellent adjustment. He has had one-man shows of his paintings in various galleries. In this case, what made for such a favorable recovery was the absence of psychopathic traits, along with the freedom from psychotic thinking, once he stopped the marijuana.

Heavy marijuana abuse in a psychopathic person can lead to a quite different result, and to the kinds of violent crimes that in the public eye smack of evil. This was the case with what the papers described as the “grisly slaying of dancer, Monica Berle” in 1989.35 Her killer, who had met the dancer through a friend and who had begun to live with her, both used and dealt marijuana heavily. He had developed grandiose delusions, imagining he was “the Lord,” whose mission he felt was to “take leadership of the satanic cultists to make sure they do everything that has to be done to destroy all those people who disagree with my church…those who call me evil, who say I am not the New Lord.” He called himself “966” because he said that three lords came floating out of a wall to appear to him in 1966. After killing the dancer, he dismembered her body, boiled her head in a kitchen pot, and placed bits of her flesh in buckets he then kept in storage facilities. Having cooked her flesh, he then, in an act of grotesque generosity, dispensed some to the homeless in his neighborhood as “meat.” As an earlier indication of his contempt for the suffering of living creatures, throughout his adolescent and adult years he had tortured cats and dogs. This may have served as a prelude to the manner in which he murdered and desecrated his victim. Because this man was psychopathic, but had been psychotic only temporarily owing to the effects of drug abuse, he should be placed in Category 16: multiple vicious acts that may include murder. Curiously, he did not, to the best of our knowledge, indulge in cannibalism himself. Instead, he dismembered his victim's body to destroy evidence. That he gave some of her flesh to strangers as though it were properly edible meat created a kind of cannibalism-by-proxy. This, of course, also contributed to the disappearance of her body, so as to thwart the authorities in their prosecution of the case.

Sometimes chronic abuse of powerful illicit drugs such as “crack” cocaine can lead to a psychotic state resembling paranoid schizophrenia: delusions of persecution are prominent, as are hallucinations commanding one to commit violent acts. Whether Lom Luong was hearing such voices is not known, but he was a heavy crack user. He had gotten into an argument with his wife (both were immigrants from Vietnam) and one day threw all four children off a bridge in Mobile, Alabama. Their ages ranged from three to just four months. He initially confessed, then retracted, claiming a certain woman had taken the children to feed and clothe them. But then over a period of several days, the bodies of the four children were found. Luong was called a “monster” in the press, and people who were against the death penalty wrote letters stating that they were still basically against it but wanted to make an exception in Luong's case.36 Luong's murder of his children, shocking because he killed all four at once, made headlines—but only briefly, because of his humble socioeconomic position. The situation was quite different when Andrea Yates drowned all five of her children in Texas in June of 2001. She had been valedictorian of her high school class and had worked as a nurse until she married Russell Yates in 1993. Her husband persuaded her to remain at home caring for the children, even home-schooling and home-churching them. Russell was a computer specialist at NASA earning what was then an upper-middle-class income. For a time, however, he insisted they all live in a Greyhound bus that he had converted into a mobile home. There was a family history of depression on Andrea's side; she'd had postpartum depression (leading to a suicide attempt) after the birth of her fourth child, and a more severe depression after the last child, who was only six months old. It couldn't have been easy to live—almost imprisoned—in such cramped quarters.

This may have contributed to her final depression, which reached psychotic proportions. She heard voices and had felt for some time like killing her children, which was most inconsistent with her otherwise unusually caring nature. The psychiatric care she received toward the end was not of the best quality: she was given two different antidepressants and an antipsychotic drug, but the latter was dropped, unwisely as it turned out, shortly before the murders. By that time, the family had moved to a house—where she drowned her children one by one in the bathtub.37 Granted that killing four or five of one's children makes a bigger impact on the public than killing only one, the publicity in the Yates case, in contrast to the Luong case, was a function of the higher social position of Andrea and her family. Described as a “shy woman, bereft of self-esteem, overwhelmed by raising her five children with little help, yet unable to admit her frustration,”38 she, as a person, hardly met any of our criteria for “evil.” Once the matter came to trial, the shocking nature of the act, however, coupled with the publicity, led to an initial rejection of the insanity defense and to a sentence of life imprisonment. This was eventually overturned, and Andrea was sent to a forensic hospital, where she should have been sent in the first place.

There is something about cannibalism in the course of a crime that many of us react to with a revulsion more intense even than our reaction to incest, and not matched by any other act of violence, with the exception possibly of castration or other types of mutilation. Perhaps this has to do with the primitive nature of cannibalism, as though it represents our earliest, yet socially taboo, longing. In my psychoanalytic training, I was taught the developmental stages through which, in Freud's understanding, the infant passed on the way to psychological maturity. The first stage was called oral cannibalism, based on the assumption that the newborn wanted not merely to suckle at its mother's breast but to devour all of her. But newborns can't talk; they can only give us hints about what they're longing for. I think the jury is still out on this one. But I understand how predictable it is that we shudder when we hear about cannibalism: the crime involves, after all, the total annihilation of a human being—someone just like ourselves—not by an alligator or a tiger (which we don't hold to the same standard) but by another human being who was willing to trample on this most sacred prohibition in the social code. This is what underlies, I believe, the universal reaction of horror, and of evil, when we hear of a cannibal murder—especially when committed by a “crazy” person acting on impulse. He could, to our way of thinking, attack anyone at any time in a totally unpredictable fashion. When twenty-one-year-old Mark Sappington began killing on impulse and then cannibalizing four people in Kansas City, Kansas, and drinking their blood as well, he quickly earned the soubriquet “the Kansas City Vampire.”39 Sappington was schizophrenic: someone whom most people knew as a charming young man with a ready wit. But under the influence of his psychosis, he heard voices commanding him to drink the blood and devour the flesh of whichever stranger he might meet next on the street. Some of the victims, however, were people he knew. As with many high-profile and particularly horrific crimes by mentally ill persons, the disposition in court is a mixed one: he will be held in a forensic hospital—but for the rest of his life.

Despite improvements in the care of the severely mentally ill over the past twenty years, imperfections in psychiatry and the law still allow some dangerous persons to slip through the cracks. We are, however, much more aware of risk factors in mentally ill people that either lower or heighten the likelihood of a violent outbreak. Many of these factors have been worked out by law enforcement personnel40 and by mental health professionals.41 Some of the risk factors one watches for in trying to predict violence in the mentally ill include command hallucinations (in which a person hears a “voice” urging him to do a certain act, often enough a violent act); delusions of persecution (the belief that people are out to do you harm, for example); recent purchase of a weapon or camouflage gear; fantasies of revenge; abuse of alcohol or drugs; a criminal history—especially if marked by previous episodes of violence; head trauma; being male; and conditions such as schizophrenia or manic-depression. Other risk factors include personality abnormalities where certain traits are in abundance, such as paranoia, antisocial behavior, or psychopathic behavior. Mentally ill people showing only a few of these factors may be no more at risk for violence—much less for murder—than any average person. Others, showing many such factors, especially if previous violence and recent drug abuse are in the picture, are at far higher risk. In some tragic cases, however, our awareness of just how many of these red flags were present is raised only after a violent or lethal act has occurred. The next example shows how a tragedy could have been averted, had we known beforehand what we knew only in retrospect.

A thirty-nine-year-old man had first been diagnosed as schizophrenic when he was twenty-two. He had been in and out of hospitals numerous times in the interval, sometimes because of outbursts of anger and violence toward his parents. He had never worked and lived at home all during this period. It was his refusal to keep taking the medications he had been given that led to his becoming actively psychotic again and again, ending up for brief stays in the hospital on each such occasion. He would often hear accusatory voices and felt people were “after him.” He had peculiar habits, such as wandering the streets at all hours, picking up cigarette butts, or taking twenty showers a day. His parents divorced during his adolescence, after which he lived alone with his mother. It was when she had to be placed in a nursing home that his life unraveled once again. By this stage, his mother had grown afraid of him and insisted he not visit her. When he attempted to do so, he was restrained by the staff, toward whom he then lashed out, necessitating police intervention. This happened twice, and both times he was taken to an emergency room to have his mental state evaluated. He was then admitted for observation and given appropriate medications, but was released after two days. Little inquiry was made into his lengthy psychiatric history. Nursing a grudge against the first psychiatrist who had examined him years before—and who had recommended he be hospitalized involuntarily—he now decided to rob that doctor and use the money to spirit his mother and himself far away where they could continue to live together. To that end, just two weeks after the episodes of violence at the nursing home, he gained entrance to the doctor's office, carrying a suitcase filled with knives, duct tape, and other paraphernalia related to a crime and to escape. Whether his initial intention was to harm or kill the doctor was unclear, but he did begin to attack the doctor with knives. Hearing the commotion, a doctor who shared the office suite ran to the rescue of her partner—only to be attacked by the man with a meat cleaver and knives, and with greater force than had been used against the first doctor. The first doctor survived. The second died. Whereas a good deal of planning went into the attempted robbery of the first doctor, the murder of the woman was done on impulse. The attacker escaped from the building and was at large for several days before he was captured. Given that the victim was a well-known and highly respected psychologist, her murder instantly became headline news.42 The first headlines were all the more glaring because the “madman was still on the loose,” a phrase that maximized the element of fear in the public.

As for the killer, the thorough examination he underwent after the murder showed that he had—with the exception of drug abuse—almost every known risk factor for predicting violence (including those specific for the mentally ill). There was a fantasized rehearsal of the crime, acquisition of weapons, lowered inhibition (thanks to his having stopped taking his medication), obsessional preoccupation with the doctor from the past, recent and past violence, involuntary hospitalizations on many occasions, a perception of injustice, active delusions, and command-type hallucinations. These were all within the context of chronic paranoid schizophrenia, in a male, where the risk is greater than it would be for a female. Unfortunately, the emergency room doctors who saw this man in the days before the murder had neither the time nor perhaps the intuitive sense to know that this man was at high risk for imminent violence. He belonged to a small group of mentally ill persons whose risk for violence in the near future was perhaps 90 percent, though their risk for actual murder would be much lower. He did not belong to the vastly larger group of mentally ill people for whom the violence risk was 1 or 2 percent, and for murder risk—negligible. Doctors in private practice don't have metal detectors as you enter their offices, nor would they always be of help. Dr. Wayne Fenton, associate director of the National Institute of Mental Health in Maryland, was killed by a schizophrenic patient he saw in his private office in 2006; the patient had used only his fists.43

What is hard for the public to understand is that for any given individual, going about the business of ordinary life, the risk of being harmed seriously, let alone killed, by a mentally ill person who has gone berserk is of about the same order as being killed by lightning. Yet the first seems evil and disproportionately high; the lightning strike we regard (more accurately) as bad luck and exceedingly rare. This has much to do, I believe, with the fact that within the animal kingdom, the animal of greatest danger to a human being is of course another human being. And since we are the only animal capable of evil, death—especially a brutal one born of impulsive rage at the hands of our fellow man—is often interpreted as…evil.

To put this point in clearer perspective, the public's emotional reaction to a shocking murder, especially to one that involves mutilation, extreme suffering, and degradation of the victim(s), torture, and the like, is altogether understandable. Accompanying this emotional reaction is, often enough, the word evil. Evil, when we say the word, is the verbal counterpart of the horror certain acts elicit. The public needs no education about this: the reaction is part of our culture, part of our nature. I say “our” here, referring to the fact that the vast majority of people, whatever murderous thoughts they may have from time to time when angered or grievously disappointed, do not lose control and do something evil. People have less reason to be afraid of the mentally ill person who kills a family member, however gruesomely, than of a psychopathic serial killer or a recidivist rapist—whose danger to the public is far greater. In between the once-in-a-lifetime act of the psychotic person who kills a parent and the psychopathic killer is the mentally ill person who is violence-prone and resistant to treatment. He, like the schizophrenic man who bludgeoned the psychologist, lives in a chaotic manner, does not comply with his treatment regimen, and is at great risk of harming others in the future. The mentally ill person committing an act of the sort we call evil is responsible for that act—but is considered to show “diminished responsibility” because of the illness. A good deal of the responsibility in a case such as that of the man who killed the psychologist rests on the shoulders of the “system” that was imprudent in releasing him from residential care in the first place. He had a long track record of defying medical advice and of menacing others. The medical system had a long track record of failing to ensure that he was kept within the four walls of a hospital setting—that protected him from his tendency to become ill and violent again, and that protected the public from what he was likely to do if prematurely released into the community.