Canto XI, ll. 25–27

| Ma perché frode è de l'uom proprio male, | But because fraud is an evil proper to man |

| più space a Dio; e però stan di sotto | it is more displeasing to God, and therefore |

| li frodolente, e più dolor li assale. | the fraudulent have a lower place, and greater pain assails them. |

The serial killers whose backgrounds and deeds we analyzed in the last chapter could easily be labeled as evil: all of them murdered repeatedly, and half of them subjected their victims to prolonged torture. Predictably, the word evil was used in the courtroom, in the media, and in the comments by the public when describing either the pain these victims were made to suffer or the men who had inflicted this cruelty. The victims of serial killers are almost invariably strangers; when their deaths are discovered, law enforcement and crime scene investigators become involved, headlines get written, and the community is alerted (and understandably frightened). This is public evil. But there are similar acts that take place within the family—and that often go undetected for long periods because the family is a sacrosanct unit not readily invaded by those outside.

English law is particularly famous for advancing the thesis that a man's home is his castle. This was underlined in a famous murder case in the English midlands in 1860, when a three-year-old boy, Saville Kent, was murdered and mutilated by one of the inhabitants in an upper-middle-class manor house. The local police were loath to examine the family, let alone to point the finger at one of its members. With great reluctance a Detective Wicher from London was finally summoned to investigate, even though this meant “violating a sacred space.”1 One of the local papers had this to say: “Unlike the tenant of a foreign domicile, the occupier of an English house, whether it be mansion or cottage, possesses the indisputable title against every kind of aggression upon his threshold…. It is this that converts the moorside cottage into a castle.”2 Thanks to Detective Wicher's unwanted intrusions, he was able to piece together who was the responsible party and why it was that the sleeping boy's throat was slit in the middle of the night, his body unceremoniously dumped in the family cesspool. It was not the butler. It was his sixteen-year-old half sister Constance, who had become morbidly jealous of the attention bestowed upon the little boy by her stepmother—her own mother having died, insane, when Constance was eight. What Wicher had the misfortune to uncover had been hidden behind a “mesh of deception and concealment.”3 His detective work earned him the opprobrium of the townspeople, who now had to confront the fact that “one of their own”—from the highly respectable family of Road Hill House—had murdered the boy. Just as in detective stories and murder mysteries—which the Road Hill House case actually inspired4—many family members were initially suspects, and each had something to hide, which led them to lie, dissimulate, and refuse to cooperate with the police, even if they were innocent.

Fast-forward 150 years, and the family is still the sanctuary and safe house it is—under ideal circumstances—supposed to be and usually is. But sometimes terrible things can go on inside the home that none on the outside are at all aware of. Similarly, when murder, mutilation, torture, crushing humiliation, and other forms of inhumane treatment within the family are eventually brought to light, we are as quick to respond with the term evil as our instant reaction—just as though the same kind of crime were committed by a stranger. Often our reaction is even stronger, because we inherently assume that parents, for example, would be far less likely to commit such an outrage against their own flesh and blood.

I had planned at first to title this chapter Parents from Hell, but I had to acknowledge that terrible crimes, including torture, may have their source in family members other than the biological parents: spouses, for instance, or siblings, surrogate parents and caretakers, and even children. Some of the examples here come from newspapers and magazines rather than from full biographies. From these briefer sources, we get to know more about the who and the how than about the why. Since this is a book that explores the “why” question, I apologize in advance for not being able to share as much about the underlying causes as you and I would like to know.

PARENTS FROM HELL

Recently in Austria, an incident came to light (literally) that is unparalleled in the annals of crime. Josef Fritzl, a seventy-three-year-old engineer in the southern Austrian town of Amstetten,5 fathered seven children by his wife Rosemarie. In 1977 he imprisoned one of his daughters, Elizabeth, age eighteen, in a bunker he had carefully constructed underneath his house (a project begun several years before her imprisonment). He first drugged her with ether, then dragged her into the bunker, handcuffing her at first to a metal pole—there either to be raped and fed, or not raped and starved. We can hear the words of Leonard Lake echoing in the walls: “Your choice!” She “chose” incest. In that dark cellar, Fritzl fathered yet another seven children through incest with Elizabeth. His daughter and her children did not see the light of day until twenty-four years later, when Elizabeth was let out for the first time, at age forty-two, because her first-born (then nineteen) had become gravely ill and was obviously medically unattended. The story came out when the girl was hospitalized.

This was not the first of Fritzl's offenses. Earlier, he had tossed one of Elizabeth's babies, allegedly a stillborn, into the furnace.6 He had once been in prison for rape years before. A woman from Linz came forward after the children had been freed accusing Fritzl of having raped her years ago.

We know very little about Fritzl's early life, other than that he grew up in the Nazi era and had a “domineering mother whom he loved desperately.”7 During his adult life, he had also been domineering, insisting on total obedience. He was good at lying, too—telling his wife that Elizabeth had “run away to join a Satanic cult” when she disappeared (to the cellar bunker just below where his wife was standing!) in 1977. Fritzl had apparently turned away from his wife when he felt the bloom was off the rose regarding her looks; she had also become good and tired of his bullying. Elizabeth at eighteen was prettier and, once a captive, left her father free from any worries that she would leave him.8 As for Elizabeth's children, they had spent their entire lives like the imaginary prisoners in Plato's Republic, chained in such a way that they could only see shadow-images in two dimensions cast by a fire in back of them like puppets between the fire and the prisoners.9 They had hitherto glimpsed the outside world only on the two-dimensional screen of the television and were dumbfounded when, released to the light of the day, they saw real three-dimensional cars and houses and, most astonishing of all, the sun. Equally astonishing to those of us familiar with American law, sex offenses older than ten years are wiped off the slate in Austria, and even Fritzl's crime carries a sentence no longer than fifteen years. So we are left with the “why” question.

Aside from Fritzl's boundless narcissism and psychopathy and his contemptuous disregard for the well-being of his fourteen children (Elizabeth, the six now shamed by their father's scandal, and the seven children born of incest and burdened not only with that shame but also with their enforced ignorance of the real world), was he also hoping to create a new race of people, all with blood-loyalty to Papa Fritzl? There is some precedent for this. In Philadelphia during the mid-1980s, self-styled preacher Gary Heidnick chained a number of black women to the wall of his cellar, where he tried to impregnate them with the goal of creating a race of people loyal to Papa Heidnick.10 The experiment was a flop: the tortured women didn't conceive, and Heidnick killed and dismembered them, burying their remains in the backyard. Heidnick committed suicide in prison, whereas Fritzl, in his post-capture photos, and although called “evil” in the press, appears gleeful.11

I can't help interjecting a note about evolutionary psychiatry at this point. It has to do with the idea of “fitness.” Fitness, from the standpoint of evolution, is a measure of how many offspring an animal leaves into the next generation. In the case of humans, this means how many living children you have—even if you've been a dreadful parent. An antisocial man killed in a barroom brawl at age thirty-three but who has fathered four kids he doesn't even know about shows more “fitness” than an eighty-year-old, law-abiding parent of two children. So Papa Fritzl, with his fourteen children (well, half of whom are also his grandchildren) showed greater “fitness”—more strands of his DNA into the next generation—than I with my two sons or you, the reader, with however many children you may have, which is probably a good deal fewer than fourteen. This helps explain why there is always a fair percentage of antisocial and psychopathic persons in the community. The less extreme examples manage to be successful: conning and swindling their way through life, doing things that fall a bit short of what we would call “evil.” Their number never dwindles; their “type” does not die out.12

When it comes to harming children, and even more so, to the killing of children, the measure of evil becomes almost meaningless. Nothing seems worse, so there are hardly any gradations. Still, some people—not all—tend to react more strongly when they hear of an older child being harmed than a newborn, because toddlers or young children have already begun to establish themselves as persons and to develop distinct personalities. Likewise, it seems futile to argue whether a parent harming or killing a child is worse than a stranger doing so—or vice versa. When parents kill a child, the act is a transgression of the most sacred bond: evil writ in the largest letters possible. Yet the ripple effect may be smaller, like a pebble tossed into a small pond, compared with a stranger killing a child, where the ripples spread out over a larger lake. For when a stranger kills a child, besides whatever suffering the child may have endured, there is then, added to the picture, the incalculable suffering of the parents and all the other relatives and family friends. Killing one's own child strikes us as monstrous precisely because it was a parent that did it. Killing someone else's child strikes us as monstrous because of the widespread “collateral” suffering by the family members, over and above whatever happened to the child.

It is the mark of the psychopath that Josef Fritzl, once his story came out, objected to being called a “monster” (as he was by the press and just about everybody else except the defense attorney) and pretended instead to be “crazy.” As for the monstrosity of his long imprisonment of his daughter, the incest, the imprisonment of her children, their being cut off from access to the outside world, here physical torture and psychological torture are combined. The horror of torturing of someone else's child has already been confronted in chapter 6.13 Because torturing a child seems like the lowest depth to which a human being can sink (I say “seems,” since there is always a depth still lower than any you can imagine), torturing one's own child may be, for most of us, evil's bottom-most layer—well below the lowest layer that Dante dared to envision in the Ninth Circle of his Inferno. This brings us to Theresa Knorr.

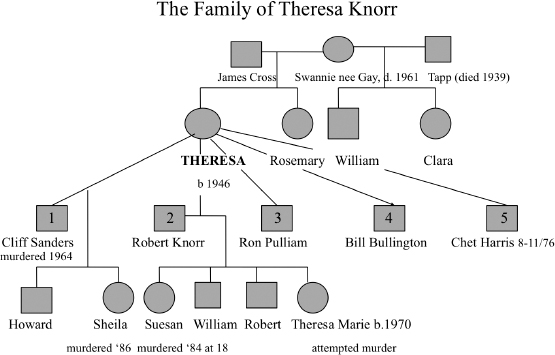

Theresa Jimmie Francine Cross Sanders Knorr Pulliam Harris, more conveniently known as Theresa Knorr (after her second husband), was born in California in 1946, the younger of two sisters (plus two older half-siblings by their mother's earlier marriage).14 She was jealous of her sister, even though she was the favorite of their mother, Swannie Cross. But when Theresa was fifteen, her mother collapsed and died in her arms, after which Theresa went into a deep depression.15 Her father became ill a few years later, which spurred Theresa to marry the first man who proposed to her. At eighteen she became Mrs. Clifford Sanders. They quickly had a son, Howard, but Theresa was inordinately possessive of Cliff and accused him of infidelity. On July 6, 1964 (the day after Cliff's birthday), Cliff decided to leave the marriage. As he was just about out the door, Theresa shot him in the back with a rifle, killing him. Already pregnant with their second child, she persuaded the court this was in “self-defense,” and she won an acquittal from Judge Charles Johnson. She and the judge were to meet several more times.

Theresa began to drink heavily, giving birth to a daughter, Sheila, in 1965. A year later she met a marine, Robert Knorr, got pregnant again, and discussed marriage. She gave birth to another daughter, Suesan, two months after she and Robert married. A son, Robert, came the next year in 1967. The marriage was failing because Robert's job took him away frequently. Theresa now became abusive toward the children: she would slap them for not being completely still and would lock them in the closet. At twenty-three she divorced for a second time and remarried two years later, this time to Ron Pulliam. That marriage lasted all of a year, as he resented her making him a “babysitter” for the three children while she went out partying, drinking, and, eventually, cheating on him—with Bill Bullington. Alcohol became her main consolation until she met yet another man willing to marry her: Chet Harris, who married her three days after they met and divorced her three months later. Judge Johnson presided over both the latter two divorces.

It is not recorded whether the judge was beginning to have second thoughts about the trustworthiness of Theresa's “self-defense” plea after she killed husband number 1. Stuck now with six children and no husband, Theresa began drinking more heavily than ever and became more abusive with her brood. At this point, there were more players in her life than in the average Shakespearean play. I have tried to make it easier for the reader to follow via a family diagram (see figure 8.1). Unfortunately, the children could do no right by their mother: if they said they loved her, she felt they were trying to appease her; if they failed to say so, she regarded them as evil.16 She beat them, punched the girls repeatedly, and threw knives at them, especially when Suesan ran away for a brief spell. Picked up by a truant officer, Suesan tried to tell the authorities about her mother's abusiveness, but Theresa said the girl was lying, and she was returned to her mother's tender mercies. By now Theresa, grossly overweight and no longer so attractive, became crazily jealous of her pretty daughters and began to force-feed them with macaroni and cheese so they would be fat and unattractive too. She would burn Suesan with cigarettes and claim the girl had “VD” and was a “witch.”

Figure 8.1

In 1984, when Suesan was eighteen, Theresa and her son Robert took Suesan to a remote spot in California's Sierra Mountains, where Theresa had Robert douse his sister with an accelerant (probably gasoline), setting her afire. Suesan's body was charred beyond recognition; Robert was warned he would be “next” if he ever told. Two years later, it was Sheila's turn: Theresa locked her in a closet and bound her limbs to a metal pole until she confessed that she had “VD.” The girl confessed, despite her innocence, but that won her only a brief reprieve. Theresa locked her in the closet again, this time leaving her to starve to death. The youngest daughter, Terry, had run away and was supporting herself by prostitution; when she tried to tell the police what went on in her home, she was not at first believed. Theresa was at last brought to trial and convicted in 1993 and sentenced to life in prison for the torture-killings that the judge called “callous beyond belief.”17 Because Suesan's body could not at first be identified, and because of the enforced secrecy and deceptiveness about Sheila's death, Theresa got away with murder for about seven years. At the time of her arrest she was working as a paid companion of an elderly woman.

There are many child murders as horrifying as Theresa's, their grotesqueness triggering the reaction of “evil.” Two morbidly religious mothers in Texas, for example, shocked the public—one with the murder of her two children by smashing their skulls with rocks; the other, by severing the arms of her ten-month-old daughter, intoning the words “Thank you Jesus, thank you Lord,” when the police came to take her away.18 But those mothers were certifiably insane. The level of evil becomes reduced when we take into consideration the mitigating circumstance of their madness. Like other psychotic mothers who murder very small children, the explanation (from a psychiatrist's point of view) for such behavior can lie in the overwhelming tasks of motherhood, coupled with the inability to let this difficulty register in one's consciousness (because of the psychosis). Hence the formation of a face-saving delusion: “I must consign these children to God,” or “This child is the devil and must be destroyed in order to save the world.” But Theresa Knorr was not insane. Twisted, paranoid, afire with jealousy…all of that, but not insane. As a cold and cruel torturer of her own daughters (and corrupter of her sons), Knorr belongs to the extreme end of the Gradations of Evil scale, where those who torture in a prolonged fashion reside, whether or not the end result is death.

The Knorr case is reminiscent of another case of child burning in 1983. A career criminal, Charles Rothenberg, when involved in a custody dispute with his ex-wife, decided to kill his six-year-old son, David, and himself. To that end, he gave the boy a sleeping pill, poured kerosene over his body in their motel room, kissed him good-bye, and set him on fire. Rescued by another guest, David suffered third-degree burns over 90 percent of his body, losing fingers, ears, nose, and genitals during the attack.19 Because the child survived (to which end thirty-five skin grafts were needed), Rothenberg received only a thirteen-year sentence for attempted—as opposed to completed—murder. As all too often happens in these “murder-suicide” cases, the parent loses his nerve; Rothenberg did not kill himself. But he at least confessed to what was called at the time “one of the most unforgettable crimes ever committed against a child”20 (this was a full year before Theresa Knorr swung into action). When he was released after seven years, Rothenberg said in a letter, “Do I deserve to be set free? No! It's an unforgivable act.”21

Terribly disfigured at first, David Rothenberg has made an amazingly good adjustment: after completing a film course at the University of California, he now hopes to pursue a directing career.22 He commented, “Charles is an evil man, and I feel that he should just take responsibility, because no one else lit the match.”23 That his father was able to confess and express remorse—and had not engaged in systematic torture on any previous occasions—does at least place him on a wider island of humanity than the one occupied by Theresa Knorr. Also the “why” question is a little less elusive in Rothenberg's case. Rothenberg had a worse background than Knorr's: his mother was a prostitute and he was raised in an orphanage. On the other hand, Knorr is the proverbial mystery wrapped in an enigma within a conundrum. There's no straight line one can draw from her mother's sudden death when Theresa was fifteen to the calculated torture of her daughters twenty years later. Rosemary, her sister, turned out well, as did her half-siblings. Alcohol certainly played a role—that was the “accelerant” Theresa used—but she drank to quell demons that were already circulating in her brain: loneliness, jealousy, paranoid thoughts. Perhaps there was some genetic flaw that lay behind her egocentricity that made her daughters, after her fourth husband left her (fifth, if you count her “de facto,” Bill Bullington), hated rivals instead of the solace of her lonely days. But we can only guess.

Perhaps because the concept of evil is so bound up with what is shocking and horrifying, we usually reserve the term for cases that are unlike anything we have ever heard of before. They are unique. Shooting a spouse caught in bed with a lover is murder, but it hardly passes the “uniqueness” test. Having seven children by one's own daughter and keeping them all locked up underground for twenty-four years is unique. A mother torturing her daughters for years on end, finally killing two, is unique.

Another, and more subtle, feature commonly found in families devastated by abysmal parenting is what I have called the Cat's Cradle Family Tree. The lines of relationship are so complex: so many marriages, divorces, children born of casual encounters, siblings, half-siblings, step-siblings, incest children, and the like, that there is no way to draw the family tree neatly on a piece of paper. The lines that go every which way—crisscrossing and overlapping—reflect the chaos and instability of these families. Often there is no set of values and rules that guides people's behavior and morals. If incest is “right,” then what is “wrong”? Murder is not “wrong.”

I once worked with a young woman in therapy whose father shot her mother to death in front of her and then told her, “What you saw didn't happen, and if you tell anyone, I'll kill you too!” The Cat's Cradle Family scenario shows up in the lives of many murderers, not just in cases of “Parents from Hell.” Other examples of complex family trees include Sante Kimes and Scott Peterson (chapter 4), Charles Manson (chapter 5), Ken McElroy and Tommy Lynn Sells (chapter 6), and David Ray and Leonard Lake (chapter 7). In the case of Sells, for example, who was Tommy's mother? His birth mother? The aunt his mother gave him to? The pedophile his aunt gave him to? And who was his father? Perhaps several of his “caretakers” read to him from the Bible, told him the right things to do. But children learn more from parental example than from words. Absent enduring, socially proper examples from loving parents, a child (especially a son) may grow up with little trust, great hatred, and no inner restraints. Anything is possible. Robert Knorr, the son Theresa Knorr ordered to burn his sister to death, later murdered a bartender.

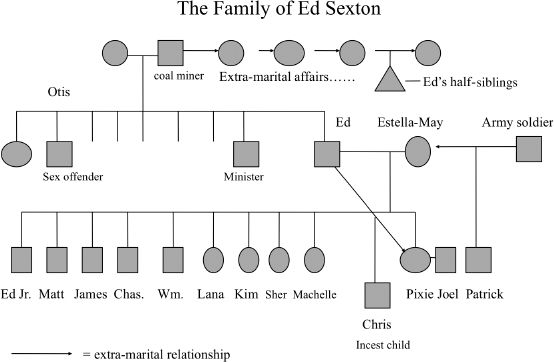

The next Parents from Hell case has these same chaotic features: unique cruelties and a twisted family tree. Figure 8.2 shows my best attempt to draw the undrawable.

Ed Sexton, born in 1942, was raised in the coal mining area of West Virginia. He was one of nine children, though there was an unknown number of half-siblings from his father's affairs with perhaps four other women. When he was ten, he set fires and killed cats and dogs. We don't know if he had the whole “triad” that included bed-wetting.

Figure 8.2

A juvenile delinquent, Ed was involved in thefts and robberies for which he spent some time in prison. Briefly in the army, he was given a dishonorable discharge for bad conduct.24 Once out of prison at twenty-nine, he married Estella May. They had a large number of children, as shown in Figure 8.2, but one was Estella May's by a soldier she met while he was en route to Vietnam, and another was fathered by Ed via incest. This daughter, Pixie, was forced to marry a man her age, so it would appear that her son was by her husband rather than by her father. Incest was rife in rural West Virginia, so it was said, and Ed tried to impregnate another daughter, Machelle, whom he raped when she was thirteen or fourteen—apparently without success (that is, without her conceiving).

Machelle may have tried to intervene when Ed went after her two younger sisters, Kim and Lana. Ed punished Machelle so severely, she had to be hospitalized. He had warned her: “You get the belt till you're sixteen, then my fist.” Actually, all the children got whipped and beaten regularly, as did Estella May, who gave as good as she got: she beat her sons continuously as well. She also held the girls down when they were being raped. Ed would beat his son Charles until he bled, making him stand naked in front of the whole family, and did the same with the other children. Ed himself ran around the house naked and encouraged the children to have sex with one another.

Another of Ed's punishments was to lock the children in a closet and spray roach-killer into the closet space. Now and then there would be a complaint, and inspectors from the health department would come over. Ed would then fake a disability, like multiple sclerosis or muscular dystrophy, and perch in his wheelchair as though unable to walk until the inspector left. Another of Ed's punishments was to tie the children up; some of them ended up lying in their own waste. He threatened to kill any of the children who dared talk to people on the outside. Ed smoked marijuana, and he was not stingy with the whiskey. He killed cats and dogs and, in the case of his daughter Sherri, he killed her pet rabbit—and then forced her to eat it. Ultimately he killed Pixie's husband, Joel, and she in turn killed the incest-child she had been made to pretend was Joel's.

One of the girls became a snitch. The news finally got out as to what was happening in the family, and both parents were arrested. In court, Ed was given a death sentence; Estella-May, life in prison.

As we saw in chapter 7, blame for an “evil” outcome is at times laid at the doorstep of foster parents or stepparents. On closer look, the stepparents might have been uncommonly caring and supportive, yet were still unable to stem the tide of adverse genetic factors (as with Gerald Stano). But sometimes stepparents really did seem to have been the main destructive force in a killer's early life (as with Charles Schmid). The wicked stepmother of the fairy tales is a figure born of real-life circumstances. Despite how kind and loving most stepparents are, there remains a small proportion—greater, nevertheless, than is true of birth parents—who kill25 or who psychologically ruin their stepchildren. The expression blood is thicker than water comes to life with particular vividness in homes where the natural children are treated with tenderness and the stepchildren with a cruelty beyond the imagination even of Hans Christian Andersen or the Brothers Grimm.

Jessica Schwarz, a truck driver in Florida, had two daughters: one by her first marriage, and another by her second husband, David Schwarz, also a truck driver. David brought to the marriage a son, Andrew, from a previous marriage to Ilene Logan.26 Ilene had been a go-go dancer who abused drugs and alcohol—and sometimes abused Andrew: she once, so it was alleged,27 hit him in the ear with a frying pan, leaving him deaf in one ear. She had various lovers, one of whom beat Andrew so badly that he had to be hospitalized. Those were the good times.

The bad times began when Andrew moved into his new home, with Jessica as stepmother. By all accounts, Jessica took good care of her two daughters, who slept in a well-appointed and well-kept bedroom. Andrew was stuck in a messy, closet-sized room—with a lock on the outside, so Jessica could, in effect, imprison him in his bedroom. Beyond that, the things Jessica did to Andrew, when added together, create a veritable textbook of sadism. She would yell at him, “I hate you,” or “I'm gonna tie you up and run you over.” She threatened to kill Andrew if he wanted to see his real mother, Ilene. She took to calling him “Jeffrey Dahmer” as though he were some monstrous younger version of the serial killer. She also called him “bastard,” “crackhead,” “bastard's baby,” and “fuck-face.” While she gave hardly any responsibilities to her daughters, Andrew was made to do most of the chores and usually with a sadistic twist: she made him clip the hedges of the lawn with a small scissors and clean his father's car with a toothbrush. She drove her daughters to school but made Andrew walk even in the rain, and she allowed no neighbors to take him in their cars. Andrew was made to stand in the yard and repeat over and over, “I'm no good, I'm a liar.” Jessica once made him wear a T-shirt at home on which was written “I'm a worthless piece of shit, don't talk to me.” The babysitter who was there offered to give him a sweater to put over the T-shirt so he would not have to admit to Jessica later that he had taken it off. Jessica once hit Andrew so hard he ended up with two black eyes and a broken nose, but she made him tell the school he had “fallen off his bike.”

The egregious failure of the local authorities to figure out the actual cause of his injuries and to take proper steps is whole other story. Jessica was once punished and made to do community service—picking up used soda cans—but she made Andrew do that work for her, forcing him to skip school on Thursdays in order to collect the cans. At times she would make the boy run down the street naked and would put tape over his mouth so that he couldn't speak to the neighbor children.

Jessica was intimidating toward her neighbors, most of whom were too frightened to warn the authorities what went on in the Schwarz household. One girl that did manage to speak to a detective about possible child abuse charges mentioned that Jessica would make Andrew sit at the dinner table with his mouth taped shut, while his sisters ate their dinner. Other neighborhood children spoke of Jessica setting a timer, and if Andrew didn't finish his supper in five minutes, she would put the dish on the floor next to the kitty litter box, making him eat it there like an animal.28

But what I found most shocking, and what would have brought tears to the eyes of the Marquis de Sade, was Jessica's forcing Andrew, if he failed to clean the kitchen to her satisfaction, to eat a roach. That alone would have earned her the seventy years in prison to which she was eventually sentenced—but she would have escaped justice altogether had she not gone the full distance and drowned Andrew in the family pool when he was ten. This is what the prosecuting attorney, Scott Cupp, had to say when Jessica was finally brought to trial: “I may not be able to define evil for you—not as a black-and-white statement lifted from the pages of a dictionary—but I can say without equivocation that I know it when I see it, and Jessica Schwarz will forever personify it in my eyes.”29

Recently, the author of Jessica's true-crime biography sent me some photographs from her teenage days, when she was Jessica L. Woods at Glen Cove High School in Long Island. The transformation from the sweet face in her high school yearbook to the tough-looking woman in her prison photo twenty-five years later seems at first astonishing, inexplicable. Her parents related in court, for example, that there was “no drug abuse or alcoholism in the family,” and that she had not herself been abused.30 But from collaterals we learn that there was indeed alcoholism in the family and that Jessica and her friends “dropped acid” (LSD) while in high school. Jessica moved in a social circle of “tough” young men and was herself known as “tough.” The picture that emerges is one that makes her transition into the sadistic bully she became not so inexplicable after all.

What is particularly poignant about the fate of Andrew Schwarz is that he was singled out for barbarous treatment, while Jessica Schwarz's own daughters, as Andrew could see for himself, were grossly favored. This situation is quite a contrast from the children of Fritzl, Knorr, and Sexton, who lived in what amounted to mini-concentration camps, all treated with equal savagery, almost all denied access to the outside world. They at least did not have to endure the added indignity of radical unfairness. But all these children suffered ego-crushing experiences—Andrew's lot simply being the worst, because Jessica reduced his status to that of a despised animal—not even a human animal—while her own daughters flourished. From a psychological standpoint, the lot of these children was in some respects worse than that of the victims in the Nazi camps—for those people usually came from loving families and knew that there were good people in the world. Many of those who survived made fairly good adjustments once they were liberated.31 The camp victims knew that the evil afflicting them came from the Nazis: a malignant group outside. For the children of Fritzl, Knorr, and Sexton, evil came in the form of one's own flesh-and-blood “protectors”—the parents. And those parents were their entire world. How could they later entrust themselves, as did Tennessee Williams's heroine in A Streetcar Named Desire—to the “kindness of strangers”?

When children are subjected to physical suffering at the hands of their parents,32 they tend to develop in one of two directions. Most are up to their necks in anger and hatred; some become violent toward others (this happens with boys more than with girls), while others take these strong emotions out on themselves and become depressed or even suicidal (this happens more with girls than with boys). Parental violence meted out to boys is a pretty reliable recipe for violence done later on by those boys. Just how reliable a recipe this is comes out clearly in a beautifully written book by criminology professor Lonnie Athens.33 Athens describes stages through which the battered child may go. First, the child is “brutalized”: severely beaten and humiliated or made to witness other family members enduring such treatment, or just encouraged by a parent to injure or kill anyone who “messes” with you. After “brutalization” comes “belligerency.” The idea of lashing out at others becomes absorbed into one's personality; it seems the appropriate philosophy for dealing with life's stresses. The next step is “violent performances.” At this stage—reached now in adolescence or early adult life—one progresses from violent thoughts to repeated violent acts against anyone who presses even lightly on one's sensitive buttons. At the end, we may see “virulence.” For Athens, this is a stage, mercifully not the inevitable consequence of parental violence, where some young persons go on to violence as a way of life by now so entrenched, so much a part of their nature, that there is no going back, no corrective treatment still available. The violence will surface as retaliation for the wrongs suffered. One cannot easily predict in advance whether the target will be the offending parent or, as is much more often the case, others on the outside who remind one of that parent. We saw this with Tommy Lynn Sells, when I asked him if he ever felt like killing his mother, given all the troubles he had after she abandoned him. Tommy said, startled that I could even think such a thought: “Anyone touch a hair of her head, he wouldn't last a minute; ya only got one mum!”

Sometimes, of course, even a daughter subjected to enough neglect and torture can pass through Athens's stages, though seldom as far as “virulence,” but certainly as far as “violent performances.” This was true in a famous British case of a girl who also “only had one mum” and who took out her hatred on others. She was widely regarded as an evil child, someone on the dark side of celebrity—so much so that everyone seemed oblivious to the primary evil in her case: the violence and sadism of her mother.

Mary Bell was born in Newcastle-upon-Tyne in northeast England, not far from the Scottish border. Betty, her mother, was a prostitute who gave birth to her when she was only sixteen. Betty was a professional dominatrix whose specialty was to whip her clients. This was a kind of controlled sadism from which she earned her keep. Her sadism was not confined to those men, however. She tried on many occasions to kill Mary before she even reached her first birthday. When Mary got a little older, she was pressed into service herself: her mother forced her to give fellatio to her “johns,” after which she would vomit the ejaculate. The men were invited to insert objects into Mary's rectum, a practice in which Betty also took part. On various occasions Betty would whip her daughter or try to drown her by pushing her head underwater. What few moments of respite Mary had from these atrocious acts were during the times Betty was in a psychiatric hospital. Some time after Mary was born, Betty began living with a de facto, Billy Bell, from whom Mary took her last name, though he was not her father. Betty never told Mary who her father was, nor is it at all likely she knew herself.34 Billy was a habitual criminal, arrested for armed robbery at some point, yet he treated Mary with gentleness and devotion: he was perhaps the only person in Mary's early life who did so.35 Betty, in contrast, would threaten her with dire consequences if she ever told what went on in the house. Hence the sexual abuse went undetected.

Her road paved with these jagged stones, it is not surprising that Mary turned to violence herself. She killed birds and cats. There is no indication that she set fires, though she did have one other element of the “triad”: she was enuretic and would often urinate on the floor on purpose, and then run away. When Mary was ten she gave the community a foretaste of what was to come: she threw her three-year-old cousin over an embankment. The boy survived, and her act was written off by the police as a childish prank.36 She then tried to strangle some little girls in a play area. But in May of 1968 she strangled to death a four-year-old boy, Martin Brown. Two months later—this time with a friend, Norma Bell (no relation) participating—the victim was Brian Howe, age three. Mary tried (unsuccessfully) to castrate Brian, apparently in revenge for the despicable sexual offenses that she had to endure. She even returned later to Brian's body and carved an “M” on his belly. As the story unfolded, it became known that Betty had tried on several occasions to throttle Mary into unconsciousness, so the murders Mary committed could be understood as reenactments of what had happened to her. And since Mary had survived these attempts, the line between unconsciousness and death was not neatly drawn in her mind—if indeed she grasped the finality of death at all at her age. She used to say that she liked hurting things that couldn't fight back.37

Both girls were soon apprehended. Norma showed some remorse; Mary did not. The court and the public regarded her for that reason as a vicious psychopath, “evil incarnate,” and as an example of Bad Seed. Because of her age, Mary was convicted of manslaughter due to diminished responsibility, rather than murder.38 For ten years she was consigned to a reformatory, then to two years in prison. Though sentenced originally to be detained at Her Majesty's Pleasure (which could amount to an indefinite period of incarceration), she appeared to have shown enough improvement after the twelve years to warrant release. As with the Archie McCafferty case (chapter 5), the public was outraged, all the more so when Mary was granted anonymity and a changed name.

Mary eventually married and had a daughter (in 1984). Her life story—ultimately one of rehabilitation and redemption—was portrayed with sympathy and psychological astuteness by Gitta Sereny, whose earlier writings had focused on evils of a different kind: the Nazi atrocities and Hitler's henchmen. She summed up: “Children are brought to the breaking point, and it is not their fault, but ours.” At first Mary herself was perplexed by the way her life had unfolded; she asked: “What made me what I am? What made me capable of evil?” Through Sereny's gentle but persistent efforts, Mary got back in touch with the sexual violation she endured, which she had for so long repressed. And it was when she became a mother herself that she could begin to grasp the enormity of her crime.39

The most likely paths she could have taken, given her history, were suicide and prostitution. That she became at first violent most likely is a reflection of some genetic influences (perhaps helped along by adverse factors during Betty's pregnancy) that made her impulsive and irritable. That she later became capable of redemption is related most likely to other and more favorable genetic influences that left her with a good capacity for compassion and reflection: these, then, interacted with what little she knew of kindness from her stepfather. Such a mixture of positive and negative influences is not rare. What is not easy to explain is why in Mary's case the good finally triumphed, despite the fact that she came from one of the worst homes imaginable, while in Jessica Schwarz's case, despite coming from a merely bad (though outwardly more ordinary) home, evil triumphed.

Mary's case also teaches us that, just as with mental illness, youth itself is a mitigating circumstance. And she was not an example of Bad Seed for two reasons: she was subjected to the unspeakable evil of her mother right up until the murders (which, paradoxically, rescued her: the court took her away from Betty and put her in the much more humane environment of the reformatory), and she did not become and remain a true psychopath, inclined to evil actions 24/7 like Jessica. There are cases that warrant the appellation of Bad Seed (as we shall see in the next chapter), but it is meaningless to apply such a label unless the home environment was uniformly favorable, the emerging personality clearly psychopathic, and there were no other factors present to explain it—not even complications during pregnancy—just the genes. Such cases are rare indeed.

The Mary Bell case illustrates another paradox: the noble principle that each man's house, be it mansion or cottage, is a sacred and inviolable space will now and again be set upside down by the Law of Unintended Consequences. Terrible things may go on in those mansions or cottages—whether the manor house of Saville Kent or the much humbler abode of Betty Bell—that remain unsuspected and undetected. This is because of the difficulty in learning what goes on in some of these “inviolable spaces” and the reluctance of the police to cross these sacred boundaries even when strong evidence comes to light. The transient evil of Mary Bell cost her twelve years of incarceration. This was fully justified by the circumstances. The perpetual evil of Betty Bell was left unpunished. She should have been sent to prison and had all parental rights terminated. Instead, and in a manner of speaking, she got away with murder. The law that safeguards the good majority protects, unintentionally, the Betty Bells as well.

Compared with birth parents, adoptive parents and foster parents are more at risk for mistreating the children under their care, just as stepparents are, and for the same reason: the lack of a blood tie to the children. Some of the most outrageous situations arise from households in which a young mother with an out-of-wedlock child—whose birth father may not even be known—now lives with an on-again off-again boyfriend. The boyfriend is sometimes referred to as the “stepfather,” but, to judge from his behavior, he is not a father in any meaningful sense of the word. His interest is in maintaining a sexual relationship with the young woman. The child in these real-life scenarios is an encumbrance in the path of the boyfriend's sexual ambitions, the more so if the child cries, soils itself, or misbehaves. This is a prescription for disaster. The risk for violent forms of child abuse skyrocket, but when and if the violence reaches the level of evil is unpredictable. We are all familiar with how much difference a half-inch makes in a gunshot case. A person shot in the mid-thigh is on crutches for six weeks with a broken femur. A person struck a half-inch toward the groin bleeds out from a severed femoral artery and dies.40 As with James Gleick's comments on chaos, small differences can make a big difference. If Jessica Schwarz made her stepson swallow some castor oil for misbehaving—and that was all—no one would have said “evil!” But she made him swallow a roach. Suddenly we are in the realm of evil. The next two cases are mansion-and-cottage versions of the same depressing story. Stepparents from Hell, Non-Blood-Parents from Hell, shielded by our noble legal system from the prying eyes of neighbors—and from the local Child Protective Services—until the day after tragedy strikes.

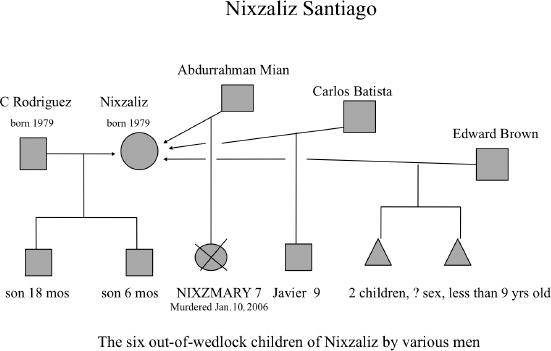

THE “COTTAGE” CASE

Cesar Rodriguez became the last of Nixzaliz Santiago's lovers and was the father of her two youngest children—both boys born twelve months apart. She lived with Cesar in a two-bedroom apartment in a poor section of Brooklyn, but she had been born in Puerto Rico in 1979, the same year Cesar was born. By the time she was twenty-seven, she had had six children by four different lovers—and almost a seventh, but the last pregnancy ended in a miscarriage in November 2005.41 What raised this couple from obscurity to nationwide public attention was the torture-murder of Nixzaliz's seven-year-old daughter, Nixzmary Brown, on January 10, 2006. Her mother did not know the father's full name; this was learned only at the subsequent trial. The family tree and its bewildering complexity are shown in figure 8.3, drawn to the best of my ability and with as much information as I could gather.

The biological father played no role whatever in the girl's life. She took her name (and not much else) from yet another of her mother's lovers, Edward Brown, by whom Nixzaliz had two other children. Nixzmary, who weighed only thirty-six pounds at her death—half what a normal seven-year-old girl should weigh—had tried to get some yogurt from the refrigerator one night. This was for the obvious reason: having been systematically starved by her “caretakers,” she was hungry. She also inadvertently jammed Cesar's computer printer with some of her toys. Enraged at her “badness,” Cesar stripped the child, plunged her head into cold water in the bathtub, and hit her head against the faucet. The latter blow gave her a hematoma (a pocket of bleeding in the brain) from which she died the following morning.

Figure 8.3

Poverty was not the reason Cesar and Nixzaliz reacted so strongly to the girl's attempt to take some food; the refrigerator was full. It was rather that they had not allowed her to eat a proper amount of food. In addition to not getting enough food, Nizmary was often locked in her room with only a litter box for a toilet. Earlier, Cesar had been in the habit of punishing Nixzmary on a daily basis by strapping her to a chair with duct tape, rope and bungee cords—and beating her. Her bruises were noticed by her teachers at school, who notified the ACS (Administration for Child Services). The ACS made no meaningful contact with the family; worse yet, the caseworker assigned to look into the family after hours, on January 10, decided to wait until the next morning. By that time, the girl was dead. Nixmary's body bore bruises all over, as well as “ugly cuts.”42

Cesar was tried first in court, and, as is customary in such cases, each adult blamed the other for inflicting the decisive wounds. It is much more likely that Cesar did the bulk of the damage, for which he was convicted only of first-degree manslaughter. The jury could not agree about the more serious possible charge of second-degree murder. It makes an interesting comment on the special semantics—just plain antics would be a better word—so often heard on the defense side in these cases. Cesar acknowledged in court that he slapped, spanked, and whipped Nixzmary with a belt, but “he didn't do it with intent to hurt.”43 No comment is necessary. By the time Nixzaliz and Cesar put in a call for medical help, the girl had already been dead for at least seven hours, so the mother, too, has much to answer for. As for the backgrounds of either adult, we know very little, so we cannot begin to answer the “why” question. Given the degree to which violence breeds violence, we can speculate that gentleness was not the main characteristic of their upbringing either. This seems like a good guess, because Cesar spoke as though Nixzmary was a wildly naughty child for whom the (as we experience it) monstrous punishments to which he subjected her were somehow normal, par for the course. At the murder trial of the mother, who blamed her daughter for her miscarriage and had called her a “devil,” Nixzaliz was convicted in October 2008 of manslaughter.

THE “MANSION” CASE

John and Linda Dollar's latest home (they changed residences many times) was in a small community some seventy miles north of Tampa, Florida. A spacious 3,800-square-foot abode with a three-car garage and a pool in the backyard, it was worlds away from the poor Brooklyn setting of Nixzaliz and Cesar. By the time the Dollars came to the world's attention, John was fifty-seven, an affluent real estate appraiser; his wife of fifty-one, a former businesswoman with a master's degree in education.44 Unable to have children of their own, they began adopting and ended up with eight children, mostly during the 1990s. The first, a daughter, was grown and out of the house by the time, in January 2005, the “troubles” came to the surface regarding the remaining seven kids.

The Dollars had started out in Tennessee, where they ran a private Christian school: the Mountain View Christian Academy in Strawberry Plains, a village of seven hundred some twenty miles northeast of Knoxville. They attended a nearby church but had a falling out with the pastor when he disagreed with their conviction that the world was coming to an end in the year 2000.45 If that were their only manifestation of religious fanaticism, the Dollars would have continued to live out their lives (even beyond 2000) in obscurity. But they had seriously twisted notions of how best to discipline children—though even these notions seem destined to remain unexposed, for they were in the habit of home-schooling their children and of confining them to the house—beyond the ken even of their neighbors, let alone any schoolteachers or caseworkers from Child Protective Services.

Of the seven children still in the Florida home, all were adolescents between twelve and seventeen. Two were the favorites of their adoptive parents and were treated well. The other five were treated quite differently. This would not have come to light but for the sixteen-year-old boy requiring the services of the local emergency room because of a head wound. He also had red marks around his neck. In addition, he was extremely underweight—and this sparked an investigation by the Citrus County sheriff's office.46 Meantime, the Dollars fled to a remote part of Utah in their SUV, only to be apprehended, thanks to their having made calls on their cell phone. They were apparently unaware that these gadgets also serve as global-positioning devices.

The authorities then discovered that all five of the less-favored adolescents were more than underweight: they were near death's door from being deliberately starved by the Dollars. Twin boys of fourteen, for example, had weights of thirty-six and thirty-eight pounds—eighty pounds less than they should have weighed, but quite in keeping with the standards of Auschwitz and Treblinka. Besides starving the children, and to ensure obedience, the Dollars took to torturing them with electric cattle prods, chains, bondage equipment, and hammers. They ripped out the toenails of one of the children with pliers, which made John Dollar's protestation in court that “it was not intentional that they be harmed in any way”47 doubly horrifying: once, because it simply is; and once again, because the Dollars, out of their morbid religious fanaticism, actually believed what they said. They were not liars.

The Dollars hit the feet of the five children with rubber mallets and canes and made them sleep in a closet with (shades of Jessica Schwarz) a lock on the outside. Or they affixed wind chimes to the bedroom door, so that if any of the unlucky five dared to sneak out in the middle of the night to garner a few extra calories from the refrigerator, the Dollars would be alerted and would swing into action. As for the boy whose condition called for emergency room intervention, investigators believed that John Dollar had grabbed the boy by the neck, raised him in the air, and then dropped him, such that he struck his head on the fireplace, sustaining a laceration.48

What it was about the three boys and two girls that made them fall out of favor with the Dollars was not made clear. At their trial the Dollars argued that they were merely carrying out their religious convictions. As John put it, “We are firm believers in the God almighty…and because of those principles, we were led to do certain things.”49 For their aggravated child abuse/torture of five children, the Dollars were each sentenced to fifteen years in prison. Linda Dollar informed the court that she had left home at sixteen because of her abusive and alcoholic father, and that her first marriage had ended because of (an unspecified) abuse.50 Given the millions of people whose early histories are replete with such conditions and worse, this cannot be the full explanation for Linda's behavior. Detective Lisa Wall sounded the right note on this matter when she said, “I will always remember the children, but will never understand what led the parents to such abuses.”51

As for the Dollars invoking God's name to justify their evil acts (what else can we call them?), one would like to think that religion-based, self-serving rationalizations about improving people by killing and torturing them have become a bit tiresome, especially after 9/11. But this is not so. I will burden you with one more example. In the West Yorkshire city of Bradford, the Crown Court found a Nigerian couple guilty of unlawful wounding and cruelty to their two sons.52 Their father had put pins through their tongues and lips, as well as pressing the tongue of one son with a pliers until the tongue swelled. The boys’ mouths had been cut with scalpel blades; both had also been bound and beaten. They were kept at home during school holidays so their wounds would not be seen. The father was a fanatical Christian preacher; his wife, also a religious extremist, would watch while her husband inflicted the injuries. He did so, he told the court, because, according to his reading of the Bible, God had had his tongue cut out. The judge, no more able than you or I to find any such passage in the Good Book, told the man: “You are calculated, determined, persistent, and cruel in the extreme…. You have sadistic tendencies and took pleasure in inflicting pain on your children. To all right-minded persons, in particular parents, the idea of causing injury to children is almost beyond belief.”53 Amen.

The parents described in the above vignettes all subjected their children or stepchildren to prolonged torture, meriting placement at the extreme end of the Gradations scale: Category 22. That category includes the act of physical torture, so the Fritzl case is atypical. Fritzl subjected Elizabeth to some physical torture in the beginning, but what followed was a predominantly psychological torture: imprisonment in a cellar for over half of her forty-two years, as well as the imprisonment of her children. We don't even know if he added, over and above the sexual torture of rape, a little nonsexual physical torture along the way, but the complete ruination of Elizabeth and the seven children surely puts him at the extreme end, regardless.

CHILDREN FROM HELL

The relationship between parents and children is a two-way street. So far we've seen some extreme examples of how parents’ acts can push their children to violence, but there are also children with genetic disadvantages, birth defects, or brain damage during pregnancy whose behavior is difficult, at times uncontrollable, and who have a very negative impact on their parents. The parents may become too punitive in response to a child's “wildness” or disobedience, resorting to harsh measures that only make things worse. A vicious cycle gets started, and one or the other—parent or child—may spin out of control, with tragic consequences. In still other families, the parents may remain in good control, consistently kind and understanding, with a disruptive child who goes on to become antisocial, even murderous. There are, in other words, a few “children from hell,” with whom the parents have done nothing out of the ordinary. These are children whose behavior, nevertheless, may even reach the level of “evil” because of some shocking act of manipulativeness or violence. Such an outcome is seen most clearly when an adopted child with many prenatal disadvantages is raised from day one by loving parents who manage not to lose control no matter what the child does. But this can certainly happen in families where the children are brought up by their birth parents. One of the examples I have chosen here concerns children raised by their birth parents; the other is about an adopted child.

THE MENENDEZ BROTHERS

E fu nomato Sassol Mascheroni

Se Tosco se’, ben sai omai chi fu.

And his name was Sassol Mascheroni

If you are Tuscan, you know who he was.

—Dante, Divine Comedy: Inferno54

The mansion-and-cottage analogy I used for the last two parent examples was a bit figurative. Nixzaliz and Cesar didn't live in anything as commodious as a cottage; the Dollars’ spacious home was a little short of a mansion. More literally, Lyle Menendez and his three-years-younger brother, Eric, murdered their parents in their twenty-three-room nothing-short-of-a-mansion mansion in the posh Beverly Hills section of Los Angeles. This was in August of 1989, when Lyle was twenty-one and Eric not quite eighteen. Their father, José, was forty-four; his attractive wife, Kitty, forty-seven. Their boys killed them execution style, using a 12-gauge Mossberg shotgun. They shot José first, then turned to Kitty, who found herself spattered by her husband's blood and brain tissue, before she, too, was dispatched with ten shots to various parts of her body. Mindful of the details required of a “perfect crime,” one of the sons then fired shots at the left knee of each parent, so that the murders would take on the appearance of a Mafia hit man at work.55 These touches did throw the police off the scent, who were reluctant to implicate the sons in this gruesome murder. The truth emerged only slowly over the ensuing months.

The Menendez parents were not perfect: José, a refugee from Castro's Cuba, was an ambitious, self-made millionaire who expected his sons to succeed at the best schools. He was as demanding of his sons as he was of his subordinates at work, which gave him the reputation of being a boss from hell. Kitty, American-born, supported her husband in these demands and contributed to the pressure that the boys felt to meet their parents’ high standards. Both parents helped the boys more than was appropriate with their homework; teachers noticed that the work they handed in from home was much better than what they were able to do in class. In their early teens, the brothers tried, unsuccessfully, to rape one of their young female cousins.

Lyle managed to get into Princeton, thanks to his father's influence, but he plagiarized a paper and was suspended for a year.56 Then, while working for his father, Lyle alienated people and was considered “nasty, arrogant, and self-centered.” Back at Princeton, Lyle got a friend to write papers for him, so he wouldn't fail. Kitty, meanwhile, was busy completing much of Eric's homework. Eric, too, was acquiring the reputation of being arrogant, loud, and rebellious. The year before the murders, the brothers began burglarizing homes in the exclusive area where their parents lived. The full recitation of their criminal actions would be too long to recite here; suffice it to say that José and Kitty were now threatening to write their sons out of their will, by way of convincing them how seriously they took their behavior. Kitty had learned from a therapist she had been seeing that her sons were “sociopaths,” lacking in conscience, and narcissistic. This was just a month before the murders. In retrospect it becomes clear that with the threat of disinheritance, the parents had signed their own death warrant.

Since the brothers were not at first considered guilty, they did inherit—and lost little time (four days to be precise) in engaging in a major spending spree, buying new cars, Rolex watches, jewelry, and…shotguns. Eric eventually confided in his therapist that “we did it,” adding that they took care to create the “perfect crime.” He mentioned that they were reluctant to kill their mother, but had to, since she was resting on his shoulder the night of the murder—and besides, he noted, with uncharacteristic compassion—she would be devastated with her husband gone. Eric's confession sounds disingenuous: after all, unless both parents were killed, the brothers would not have inherited everything. There was a long path between the murders, the realization by the police that the sons were the guilty parties, and the lengthy trials. The first trial actually ended in a mistrial, owing to the unfounded assertion of the defense attorney that the brothers had been violated sexually by their father.57 It was only at the second trial that both brothers were given life sentences. Since the Menendez parents were nothing at all like the Sextons, the Dollars, Betty Bell, or Jessica Schwarz, the “evil” in this case resides squarely in the sons. This was a case prompted by greed; specifically, what I call “accelerated inheritance,” such as Dante alludes to in the above passage regarding Sassol Mascheroni. There is no justified parricide (murder of a close relative) here, as there was in the case of Richard Jahnke Jr. (chapter 1).

“JOLLY JANE”

Though never formally adopted, Jane Toppan took the last name of Anne Toppan, the woman to whom she became an indentured servant around the time she was eight. Originally she was Honora Kelley, born in 1857, the younger of two daughters (there may have been other siblings) to Peter Kelley in Boston. Her father was a violent man and a severe alcoholic, who gave the two girls to an orphanage when Honora was six, their mother Bridgett having died of tuberculosis some years before. Ensconced two years later with the Toppans, Honora changed her first name also—to Jane. Both her father and her sister, Delia, died “insane,” which in that era meant some kind of psychosis, whose precise nature we do not know. Though Jane herself was not mentally ill until the end of her life, she began showing unmistakable psychopathic traits while at school. She was a pathological liar who spread nasty rumors about her classmates and told tall tales of a grandiose nature to the effect that, for example, her (nonexistent?) brother was a hero at Gettysburg singled out for honor by Lincoln, and that her (insane) sister was a legendary beauty affianced to an English lord.58 Released from her indentured status at eighteen, she trained as a nurse but was dismissed from nursing school for the same kinds of reasons that marred her reputation at grammar school: malicious gossip, compulsive lying—and perhaps also thievery. That dismissal was one of what seems in retrospect two turning points in her life at roughly the same time. She was also jilted by a prospective fiancé, following which, she became depressed and made several suicide gestures.

It was from this imperfect chrysalis that Jane emerged as the serial poisoner that we know today: responsible for the deaths of at least thirty-one persons, perhaps as many as a hundred. Most of these murders came in the course of her work as a private-duty nurse who, though never licensed in her profession, did manage to learn a thing or two about morphine, atropine, and arsenic. She killed almost exclusively those whom she knew. Her victims included her landlord (she then moved in with his widow) and her foster sister (whom Jane envied and hated), Elizabeth Toppan, who was at that time married to a Mr. Brigham. Later described as a pyromaniac, Jane set fires to several of the houses where she had worked. It was only after she had killed, one by one, the entire Davis family (with whom she had moved in with earlier), that suspicions were aroused enough to exhume the bodies. Though not mentally deranged at that time (she was forty-four), she was declared not guilty by reason of insanity, and was sent for life to an institution for the criminally insane in Taunton, Massachusetts.59

People at the time of her trial felt that nothing short of insanity could account for evildoing on such an appalling scale.60 A remarkable feature of her murders was that she experienced orgasm when her victims were dying from her poisons. In this respect she resembles Countess Erzsébet Báthory (mentioned in chapter 1), the only other woman I know of who can be described as a female serial sexual killer. As Jane rounded the turn of fifty, she showed paranoid traits, fearing that the hospital staff were, of all things, trying to poison her. Even toward the end of her long life (she died in the hospital in 1938), she would sometimes beckon to one of the nurses, urging her to “get the morphine, dearie, and we'll go out into the ward. You and I will have lots of fun seeing them die.”61 On the topic of evil, and comparing Jane with men who have committed serial sexual homicide, her biographer estimated that “though degrees of evil are difficult to gauge, the sheer malignancy she embodied was equal to that of her better known male counterparts.”62

In a book that attempts to rank the hundred most evil people ever to have lived, Jane is assigned the fiftieth spot, well below Hitler, Ivan the Terrible, and the Countess Báthory, but well above Leonard Lake, Ian Brady, and the Marquis de Sade.63 Though the Toppan name is no longer that well known among the public, Jane lives on secretly as the inspiration for the novel The Bad Seed by William March. This was later turned into a play and movie about a sociopathic child, who, despite having normal parents, became a serial poisoner at a young age.64 The real Jane Toppan may have been something of a Bad Seed, inheriting some unfavorable genes from her father, but as we have seen, there were many other negative forces acting on her after her birth: the untimely loss of her mother and her years as an orphan and then maidservant to the Toppans.

JEREMY BAMBER

Heredis flŸtus sub persona risus est.

An heir's grief is laughter under the mask.

—Publilius Syrus65

Coincidence or fate? On the very day I was writing this page about the murders of the Bamber family in a farmhouse northeast of London in August 1985, I thought it a good idea to check with Google about Jeremy Bamber's current fate. It had just been posted earlier that day, May 16, 2008, that Justice Tugendhat had declared, “These murders were exceptionally serious,” and added, “In my judgment, you ought to spend the whole of the rest of your life in prison, and I so order.”66

Jeremy, one of two children adopted by wealthy English landowners in Essex, was convicted of killing his adoptive parents, Neville and June Bamber, his adoptive sister Sheila, and her twin six-year-old boys, Dan and Nick Caffel by her ex-husband, Colin Caffel. The instrument was a rifle with a silencer. Jeremy was twenty-four at the time, and with all other heirs to the Bamber estate now dead, Jeremy was due to inherit their £400,000 estate. Both Jeremy and Sheila (twenty-seven at her death) had been adopted when they were about six months old from people who were considered normal and reputable. His birth father, for example, had been comptroller of stores at Buckingham Palace. Sheila had several nervous breakdowns after the twins were born and was felt to be a “paranoid schizophrenic,” though the illness may have been a postpartum psychosis of some sort. Earlier, she had enjoyed a modest success as a model in London. After a threat that she might have to give the boys into fosterage, she reacted with a flare-up of her illness.

Jeremy, at all events, insisted he was innocent, claiming that the killer was his “nutter” of a sister, who killed the other four and then turned the rifle on herself. Evidence gathered at the time suggested otherwise, and as there were no others in the house besides the family (including Jeremy), the only possible assailant was Jeremy himself.67 That is the way the Crown saw it, anyway, and Jeremy was sentenced to twenty-five years in prison—the sentence extended just now to life without parole.

The judge at the original trial said that Jeremy represented “evil almost beyond belief.”68 If Jeremy, who has protested his innocence all these years, is indeed guilty, he would be a better example of Bad Seed than Jane Toppan. By his own acknowledgement, he had enjoyed a secure and comfortable childhood, free of any neglect or abuse; his childhood memories were happy ones.69 And since he was not mentally ill, his psychopathic traits presumably must have stemmed from inherited or other prenatal sources. Some students of this famous crime currently favor Jeremy's claim and put the blame on the (allegedly) suicidal and mentally disturbed sister.70 Sheila, who also had a happy childhood, could not be considered a Bad Seed because she was not at all psychopathic. Her “inheritance” was simply a tendency to mental illness. So either Jeremy really is innocent after all, or he almost managed to stage the “perfect murder.”

We see a picture of him (readily available on the Internet) looking appropriately sad at the funeral. Was this feigned grief (as suggested by the Latin maxim above)? Or is the judge wrong all these years later, calling Jeremy “evil,” when he may not be? If Jeremy is ever released, albeit truly guilty, we can invoke another maxim by the same Latin author: Judex damnatur ubi nocens absolvitur—The judge is condemned when the guilty is absolved. Until such time as we know the truth, we at least know that in this case the only two possible suspects did what they did based solely on factors (psychopathy or psychosis) already in place the day they were born. To drop yet another Latin phrase used often at trials: Cui bono? Who benefits? If Sheila were truly suicidal at the prospect of losing her boys, she might have killed herself and maybe even the boys.71 But why the parents? No benefit to her there, even psychologically. But Jeremy almost got his hands on that £400,000. That's a lot of money even today; it was a lot more in 1985.

PATTIE COLUMBO AND THE VICIOUS CIRCLE

In what seemed at first to be a Bad Seed case—a young woman of nineteen raised in an excellent family, then conspiring with her lover to kill that family—on closer look doesn't appear so simple. Pattie Columbo was the elder of two children in a working-class Chicago family. Her father, Frank, was of Italian American and Catholic background; the mother, Mary, of English, Irish and Baptist background. When Pattie was seven her parents had a son, Michael. The parents were loving, generous, and indulgent but also strict and unyielding when it came to moral standards. The latter qualities didn't really come into the picture until Pattie reached puberty when she was ten or eleven. Like her mother, Pattie had terrible cramps before her period. She began to have nightmares in which her favorite dog fell into a roaring fireplace. Her formerly sweet behavior underwent a change: she became wildly aggressive—once smashing a hair dryer over the head of one of her girlfriends. Already at twelve she wore a lot of makeup and dressed in a vampish way. A doctor suggested birth control pills to her mother as a means of controlling Pattie's premenstrual pains, but her mother refused, thinking this would legitimize Pattie's premature experimentation with sex. Her father would make her change into more demure attire before going to school. Pattie rebelled, packing a miniskirt and low-cut blouse in her backpack, changing into her sexy clothes the minute she arrived.

A real head-turner, Pattie was statuesque, looked older than her age, was sultry and tough in front view; quite beautiful in profile. At sixteen she had a boyfriend, with whom she was at once seductive and moralistic. She refused sex and was vehemently opposed to his using pot or other drugs. For a time he dated another girl, which excited jealousy in Pattie to the point that she threatened to beat that girl up. She grew resentful when her parents would ask her to babysit for her brother. Her mother had to undergo an operation for colon cancer; when she returned home, Pattie was asked to help out around the house with chores. She refused, and her father became so angry he slapped her hard in the face. Feeling that she was no longer “Daddy's girl” and that he loved Michael more than her, she threatened to call the police. This was the beginning of the vicious circle. She made her erstwhile gentle father furious, his slap made her enraged and defiant, which made him even more furious, the whole situation spiraling out of control.

Pattie worked as a waitress at a restaurant next door to a Walgreen's drugstore, where she met the manager, Frank DeLuca, who was forty years old and married with five children. It was love, or at least lust, at first sight. They became inseparable. He taught her things about sex she never knew; she was the beautiful young girl he had hitherto only dreamed about. Pattie dropped out of high school a few months before graduation, much to the consternation of her parents, who were becoming aware of her infatuation with DeLuca.72 At eighteen Pattie moved in with DeLuca and his family. She and DeLuca would have sex in the marital bed while his wife, Marilyn, was out in the yard playing with the children. Pattie's father was so enraged at his daughter's immoral conduct and betrayal of his values that he charged over to Walgreen's with a rifle and threatened to kill DeLuca. Stopping just short of that, he swung the rifle at DeLuca, knocking out one of his teeth. Pattie retaliated by signing a warrant against her father for aggravated battery. The vicious circle was getting wider.

Finally, on May 4, 1976, Pattie and DeLuca, who by then had moved into an apartment of their own, went over to Pattie's parents’ home and shot to death her parents and thirteen-year-old brother. Michael was also stabbed ninety-seven times, apparently by Pattie. The shooting was probably done by DeLuca. The scene was amateurishly staged to look like a burglary gone bad. The police know that overkill of that sort indicates rage and hatred; professional criminals kill when they feel they have to, using much neater and more efficient means.

Pattie and DeLuca feigned innocence but were eventually arrested and tried in court. Both were convicted of triple murder and sentenced to two hundred to three hundred years in prison. The prosecution contended, “She killed her father and she killed her mother, and she killed her brother, which is the hat-trick of evil.”73 The judge told Pattie's relatives after the sentencing: “You're going to want to figure this out. Don't. Don't even try to understand the criminal mind. You can't understand it. Only criminals understand it.”74 Yet we do have to try to understand it. When Pattie's father once asked his priest, “What did we do wrong?” the priest told him: “Nothing. It could just be Bad Seed.”75 I don't think so. Maybe Pattie inherited some of her father's volatile temperament, which would have made the “raging hormones” of puberty more inflammatory than in a calmer girl. Then there was the vicious circle of parents and daughter each offending the sensibilities of the other, each handling the stronger stresses by physical means rather than by reaching accommodations through talking things out. Add to all this the important element of synergy: two impetuous lovers acting together in a way neither would have acted alone, and the path to murder becomes not so incomprehensible after all.76

In the thirty intervening years, Pattie has had a long time to cool down. Ensconced in Illinois’ Dwight Prison for Women, she has now completed college and spends her time fashioning study guide computer courses for some inmates and teaching other inmates to read. Dwight Prison lacks only a moat and a drawbridge to resemble a medieval castle. When I visited it, I noted that it was also uncommonly (for a prison) pretty on the inside. Pattie, it is said, still shows little remorse (and thus fails her chances at parole), but is popular among the women housed there: she is the queen of her new castle.

SPOUSES FROM HELL

In previous examples of husbands and wives whose spousal murders gained wide attention—and whose stories raised the specter of evil—we see people who were able to live for a time, if not in harmony, then at least in a kind of fragile truce. Nothing terrible happened until some event shook the marriage to its foundation and inspired murder. Discovery of infidelity was the triggering event for Clara Harris (chapter 2), whose behavior at work and at home was otherwise exemplary. Exposure of a reputation-shattering fraud was the turning point in the lives of Jean-Claude Romand (chapter 3) and Mark Hacking (chapter 4, note 44), neither of whom was quite the physician he made himself out to be. The desire for escape from a marriage gone stale into the excitement of an illicit affair, as it reached the boiling point and then some, propelled Kristin Rossum (chapter 4) and Jonathan Nyce (chapter 2) over the edge. It was debt that turned the moralistic crank John List (chapter 4) into a murderous crank. When he was finally identified eighteen years later, List's new wife swore that he had been a decent, honorable husband.