CHAPTER 6

SEEKERS FROM A SHATTERED LAND

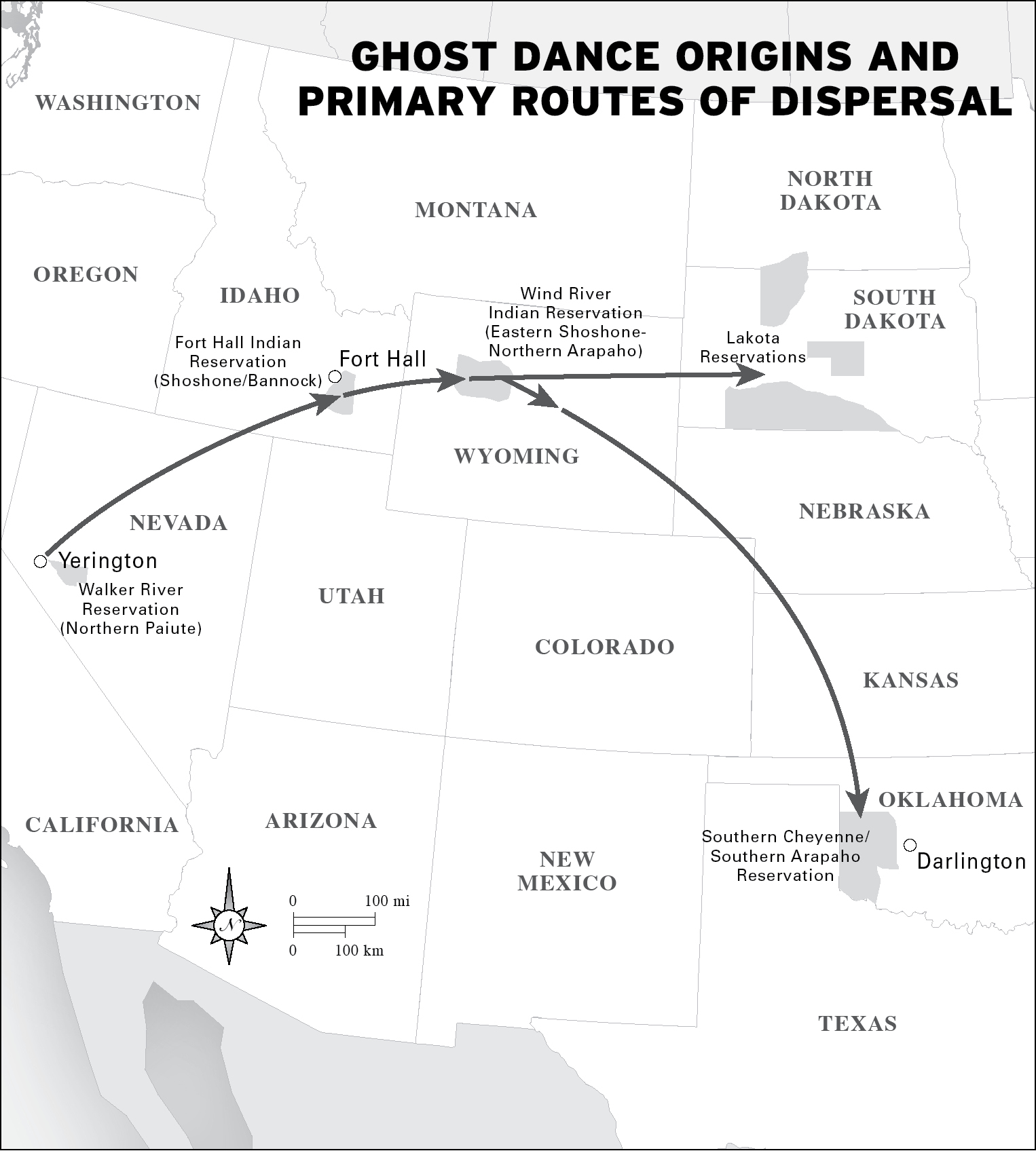

THE GHOST DANCE WAS KINDLED AS EARLY AS 1888, WHEN rumors of Wovoka’s prophecy began to travel along the bands of steel that tied the Great Basin to the Great Plains and the world. By the fall of 1889, the Ghost Dance in Nevada had become a roaring fire, fueled by the joy and exhilaration of widely scattered people who came to hear Wilson’s teachings and then dispersed like so many sparks. Where they touched down, new ritual fires often erupted, and from these still more sparks spread to ignite devotions nearby. East of the Rocky Mountains, two such blazes burned so bright as to become beacons of the new religion across the Great Plains. On the Northern Plains, in South Dakota, thousands of Lakota Sioux became enthralled with Jack Wilson’s promise of renewal and relief. On the Southern Plains, in Indian Territory—today’s Oklahoma—Southern Arapahos took up the religion with at least as much enthusiasm as Lakotas.

By following the religion as it developed among Lakotas and Southern Arapahos after it shifted to the Plains, we can avoid a common mistake. Too many histories of the Ghost Dance focus on Pine Ridge and relentlessly narrow their view of it as the story approaches Wounded Knee, stripping away its complexities and turning to political and military concerns, until the religion is so diminished as to fit in the sights of a Hotchkiss gun. Although Americans forced the Ghost Dance into a cul-de-sac at Wounded Knee, that would prove to be only one chapter in its complicated history. The religion went many places from Nevada and flourished on dozens of Indian reservations. By comparing Lakota and Southern Arapaho responses to the new teachings, we can better understand what the religion meant to Indian believers and why, in spite of the catastrophe at Pine Ridge, it flourished for decades elsewhere.

MAP 6.1. Ghost Dance Origins and Primary Routes of Dispersal, 1889–1890

In the end, the Ghost Dance offered believers, not an immediate and violent rejection of American governance, but an intense spiritual and emotional experience that facilitated their accommodation to American dominance in many areas of Indian life while simultaneously allowing them to seek out health and prosperity on Indian terms. The Ghost Dance, in other words, helped many believers accept conquest while strengthening their resolve to resist assimilation.

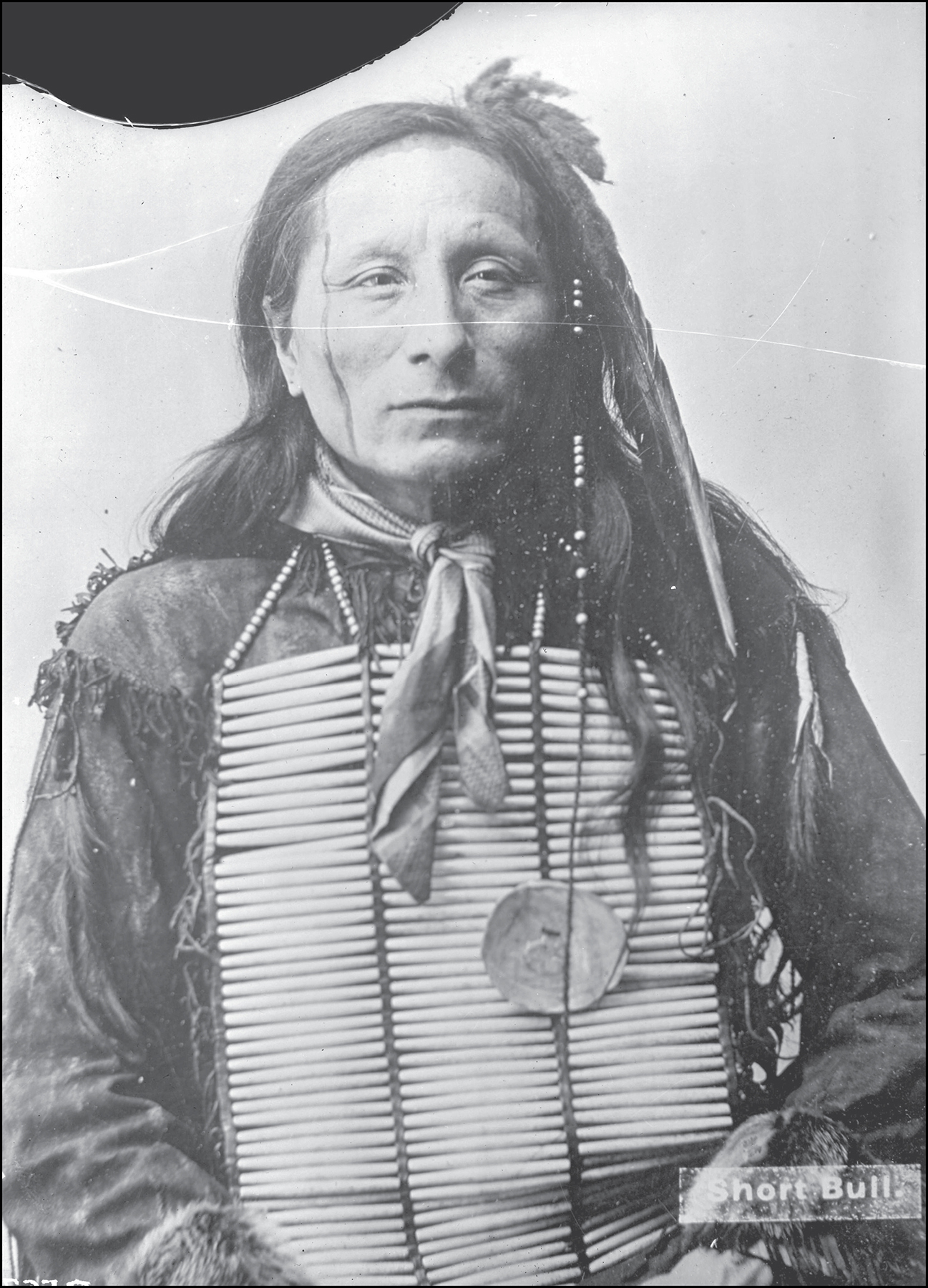

IN THE FALL OF 1889, A MAN NAMED SHORT BULL SET OUT FROM the Brule Lakota Reservation at Rosebud, South Dakota, to investigate reports of the new religion. Along the way to Nevada, he would ride trains and wagons with a diverse array of fellow seekers from far-flung places, including a group of fellow Lakota (Western) Sioux, also from South Dakota. From Wyoming came a Northern Arapaho named Singing Grass (who spoke English, a particularly valuable asset to the group); the Northern Cheyenne mystic Porcupine, from Montana; a charismatic Southern Arapaho who would become a major evangelist; and dozens of others who are lost to history.

The hardships endured in the Indian communities these men left behind on the Plains had created fertile soil for the seeds of the new teachings they would bring back. In Oklahoma, a woman named Moki grieved for her children. Her husband, Grant Left Hand, fought back his own sorrow as he worked as a clerk in the traders’ store. Nearby, a man named Black Coyote, the chief of police on his reservation, redoubled his efforts to rise from his humble beginnings even though opportunities for wealth and advancement were declining all around him. These Indians and dozens of others would soon be crisscrossing their reservations and the Far West searching out Wovoka’s teachings and carrying them to others.

Why did so many from the Great Plains embark on quests to find the new religion at this moment at the close of the 1880s? And why were so many eager to hear its message? East of the Rocky Mountains, the tribes where the religion took hold were scattered along an arc that encompassed most of the Plains and included Southern Cheyennes and Southern Arapahos as well as Kiowas, Kiowa Apaches, Caddos, Pawnees, Lakota Sioux, Northern Arapahos, Northern Shoshones, and Northern Cheyennes. The vast grassland that was their home stretched from northern Texas well into Canada, and east from the Rocky Mountains for 500 miles. Although its very name—the Great Plains—conjures images of unlimited space, for Indian people the 1880s had been a decade of crushing new limits. The disasters that had befallen Paiutes were replicated and sometimes amplified on the Plains, where every single Ghost Dance tribe was confined to a reservation, their old lands stripped away by voracious white settlers and their autonomy smothered in a reeking dependency on federal annuities and rations. With their children dying in waves of illness, their religions under siege by zealous missionaries, and their old economy in ruins—they had even fewer means of making a living than Wovoka’s people—they found it nearly impossible to imagine a future for themselves. The appeal of the Ghost Dance was the way it addressed these challenges, offering both a means to survive this harsh era and a hope of ending it in a millennium of earthly renewal.

FOR PLAINS PEOPLES, IT WAS TIME FOR EMBRACING DEFEAT. FROM north to south, Indians of the Plains had seen their autonomy vaporize in a frighteningly brief period. We might begin with Short Bull’s people, the Western Sioux, who would provide most of South Dakota’s Ghost Dancers. They were nomads who migrated from their earlier homes in Minnesota onto the Plains in the seventeenth century in pursuit of beaver pelts for trade with Europeans; by the eighteenth century, their westward expansion was vigorously fueled by trade in buffalo robes for guns and other goods. As they moved across the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers, the Lakota ascended a high, arid grassland on the western boundary of the Plains at the base of the Rocky Mountains. This grassland sits 6,500 feet above sea level, and the mountains soar up to 14,000 feet, casting a rain shadow eastward for hundreds of miles. In the sheltered river valleys of the Missouri, the Platte, the Republican, the Loupe, and other rivers, early occupants of the region—Mandans, Hidatsa, Arikaras, and Pawnees—had built earth-lodge villages, planted maize, beans, and squash, and hunted the surrounding country for meat and hides. For centuries these horticultural villagers had outnumbered the smaller groups of nomads and dominated the region.

By 1700, the intrusion of horses into this landscape had begun to revolutionize Indian economy and society, allowing them to turn grass and sunlight into speed and mobility. With the expansion of markets for buffalo robes in the United States and Europe, the gun trade increased as well. Meanwhile, new diseases like smallpox and influenza proved deadlier in the dense earth-lodge towns than in far-flung nomad camps. As these forces diminished the horticultural villages and forced them to cede territory, the bison-hunting nomadic villages, notably Lakotas, dramatically expanded in size and power.1

These were no aimless wanderers, but mobility was key to their success. They moved across and controlled the high plains by anchoring their lodge-skin villages in river valleys, which provided not only water for people and horses but also meadows for pasture, wood for cooking, and shelter from fierce winter storms. Over the course of two centuries, the Western Sioux spread up the broad gradient of the Great Plains until they reached the Rocky Mountains.2

Short Bull was a Brule (or Sicanju) Lakota, and a wicasa wakan, or holy man. Slight and small, he was born beside the Niobrara River, in today’s western Nebraska, around 1847, when the seven tribes of the Lakotas were at the height of their power. The westernmost of these tribes, the pioneers of the advance onto the Plains, were the Oglalas and Short Bull’s own Brule, but close behind and closely related were the Hunkpapas, Sihasapas, Two Kettles, Sans Arcs, and Minneconjous. Fiercely independent, numerous, and well armed, Lakotas pushed aside some enemies in their westward advance and made new pacts with others, until they had carved out a vast realm that covered most of the Northern Plains, including South Dakota, North Dakota, and eastern Montana, and extending southward through most of Wyoming and Nebraska.3

It fell to Short Bull’s generation to resist the American expansion that followed in the tracks of the Lakotas, who were reluctant to surrender lands or autonomy. Like many of his generation, he had fought in the wars against Pawnees and Crows, and now he returned to battle, this time against the American troops and settlers in the campaigns that Americans called the Plains Indian Wars.

FIGURE 6.1. Short Bull, ca. 1891. Denver Public Library, Western History Collection, B-567.

Indian resistance, for all its heroism, faced high obstacles. It had been the environmental revolution of the horse that brought the Plains nomads to the apex of their power: the speed and power of their mounts allowed them to cover more territory, hunt more bison, and carry more provisions than when they moved on foot. However, a second environmental revolution, the cheap transport across the region made possible by coal-powered railroads, brought their desolation. During the Civil War, the Union Pacific Railroad extended its tracks into the southern reaches of Lakota territory, in today’s Nebraska. Now animals and land that had been too remote from markets to be valuable could be converted to commodities like meat, hides, and grain. Chicago and St. Louis, like Virginia City, began to funnel resources from a vast swath of Indian country to the world market. The rails drew farmers, ranchers, cowboys, buffalo hunters, and others in such numbers that Nebraska became a state by 1866. For Indians, the results were devastating.

The region’s wildlife declined so rapidly as to stagger the imagination. In 1790, the Plains probably supported 30 million bison, along with abundant elk, deer, antelope, mountain sheep, and wolves. Trade in bison robes and hides, the expansion of cattle, and the settlement of the eastern prairies all cut deep into the herds. Between 1871 and 1878, some 5 million bison vanished from the Southern Plains. In the same period, millions more disappeared from the north. The last buffalo hunt among Short Bull’s people occurred in 1883. In 1889, William Hornaday, an American naturalist, conducted a census of bison over the entire Plains. He found 25 in the Texas Panhandle, 20 in Colorado, and 236 in Wyoming and Yellowstone National Park.4

Meanwhile, anticipating and facilitating the flood of settlement, the US government had mostly removed Indians from lands that whites coveted. The 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie established the Great Sioux Reservation and a series of government agencies to keep the Sioux away from emigrant trails and the railroad along the Platte River in Nebraska. Red Cloud, Spotted Tail, and Man-Whose-Enemies-Are-Afraid-of-His-Horses (who became known in the history books as “Man-Afraid-of-His-Horses”), along with their followers, began making homes on the reservation, a 25-million-acre tract of land that lay west of the Missouri River and encompassed most of the western half of the future South Dakota.5

Bands from these reservations would hunt and visit outside reservation boundaries in the early 1870s, but other Sioux bands sought to remain completely independent of the United States and refused to report to agencies or be bound by reservation limits. Led by Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and others, these Lakotas stayed free in the north. In 1876, when Custer ventured out to force them to the reservation, the holy man Short Bull was in the crush of horsemen who charged across the Little Big Horn River and drove the bluecoats down. Only when the US Army subsequently closed in on them in 1877 did Crazy Horse lead his followers to the reservation. Sitting Bull and his people ventured to Canada instead, then returned in 1881. Many of these later arrivals to the reservation had never been defeated by US forces and only surrendered because the buffalo were gone and the people were starving.6

Short Bull, who aligned with Crazy Horse, surrendered around 1877 and came to live with the other Brules at the Rosebud Agency, part of the Great Sioux Reservation. (Until the Great Sioux Reservation was broken up into smaller reservations in 1889, different tribes of Lakotas lived on the same reservation but were assigned to different administrative centers, or agencies, to secure their rations.) In Short Bull’s time, Lakotas lived in tiyospaye—small camps organized by extended family—and their acknowledged leader was a tiyospaye chief. When Lakotas gathered on the reservations, they eventually spread out in small settlements across the landscape in their old (and some new) tiyospaye camps. Many of these camps would later become towns.7

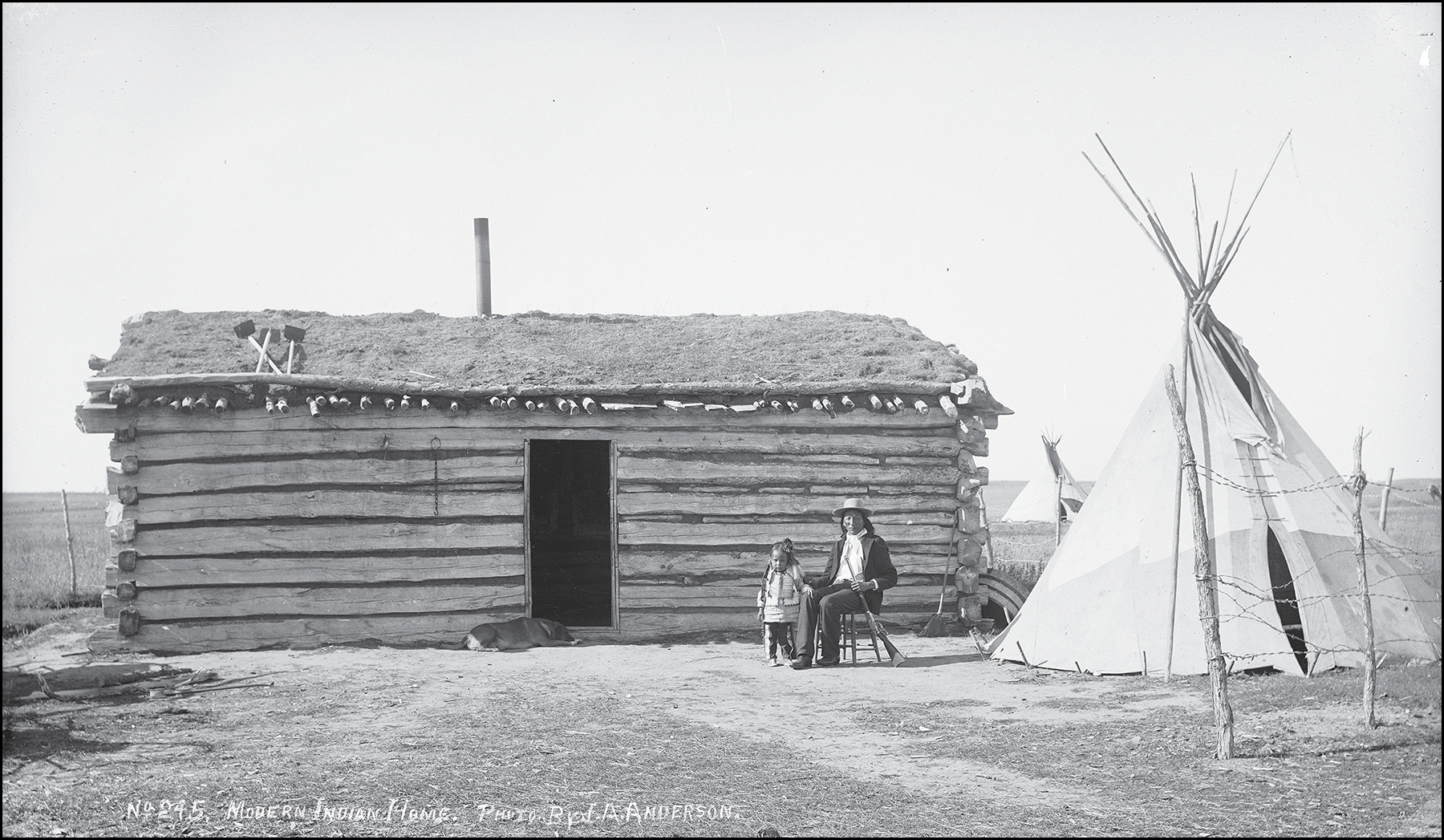

Meanwhile, Lakotas settled in small clusters of cabins and lodges along streams and rivers across the reservation. They built log cabins because they preferred them in the winter, but in the warm months—and sometimes even year-round—tipis still sprang up beside the cabins as owners entertained visiting guests or took to the old lodges themselves. Those leaders better disposed toward Americans settled nearest the agencies. Other bands settled in the hinterlands; Sitting Bull, for example, finally built a cabin on South Dakota’s Grand River, forty miles from the agency at Fort Yates. Along with the rest of the Brule band of Chief Lip, Short Bull built a cabin near Pass Creek, at the western edge of the Rosebud Reservation, keeping as far away as possible from the agent’s influence.8

SOUTHWARD ON THE PLAINS, THE STORY WAS MUCH THE SAME: nomadic peoples saw their power expand in the first half of the nineteenth century and collapse soon after. Cheyennes and Arapahos preceded Lakotas by at least a century in moving west out of Minnesota and onto the grasslands, where they eventually hunted bison from horseback. By 1850, they had allied with one another and gained control of most of today’s Colorado and Kansas. Farther west, groups of Shoshones left their home in the northern Rockies in the sixteenth century and ventured east and south into Texas, where they became Comanches. With the advent of horses and mounted bison hunting, they allied with Kiowas and Kiowa Apaches and attained supremacy over a vast region that stretched from today’s Oklahoma southward for hundreds of miles, deep into Mexico.9

Violence (US Army attacks began as early as the 1850s) and starvation (from the decline of bison in the 1870s) ultimately pushed all these peoples to reservations. Cheyennes and Arapahos split into northern and southern divisions; Northern Cheyennes and Northern Arapahos took up assigned lands in Montana and Wyoming, respectively, in the late 1870s. Earlier, beginning in 1870, Southern Arapahos and Southern Cheyennes began sharing an Oklahoma reservation of some 4.2 million acres in the western short-grass prairie. By 1875, Kiowas and Kiowa Apaches had accepted lands on the southern edge of the Southern Cheyenne–Southern Arapaho reservation. Their allies, the Comanches, settled there as well the same year.10

By this time, Oklahoma was a giant patchwork of Indian reservations. Since the Cherokee Removal in the 1830s, authorities had been assigning Indians to reservations in what was then called Indian Territory to ensure efficient management and more rapid assimilation. Southern Cheyenne and Southern Arapaho occupied the western end of this territory; to the east were more than a dozen other Indian peoples who had been shunted there. In addition to the so-called Five Civilized Tribes—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole—Indian Territory was now occupied by a wide range of prairie, Great Lakes, and other Indians, including Wichitas, Caddos, Tonkawas, Poncas, Otoes, Missouris, Iowas, Sac and Foxes, Kickapoos, Pottawatomies, Kaws, Osages, Shawnees, and Pawnees. Widely divergent in culture and language, and often historically opposed to one another, all Indian peoples in Oklahoma now faced similar conditions of reservation life and economy. New ideas spread easily in such a population, and the Southern Plains would be a particularly fertile seedbed for Indian religious revival, and especially the Ghost Dance.11

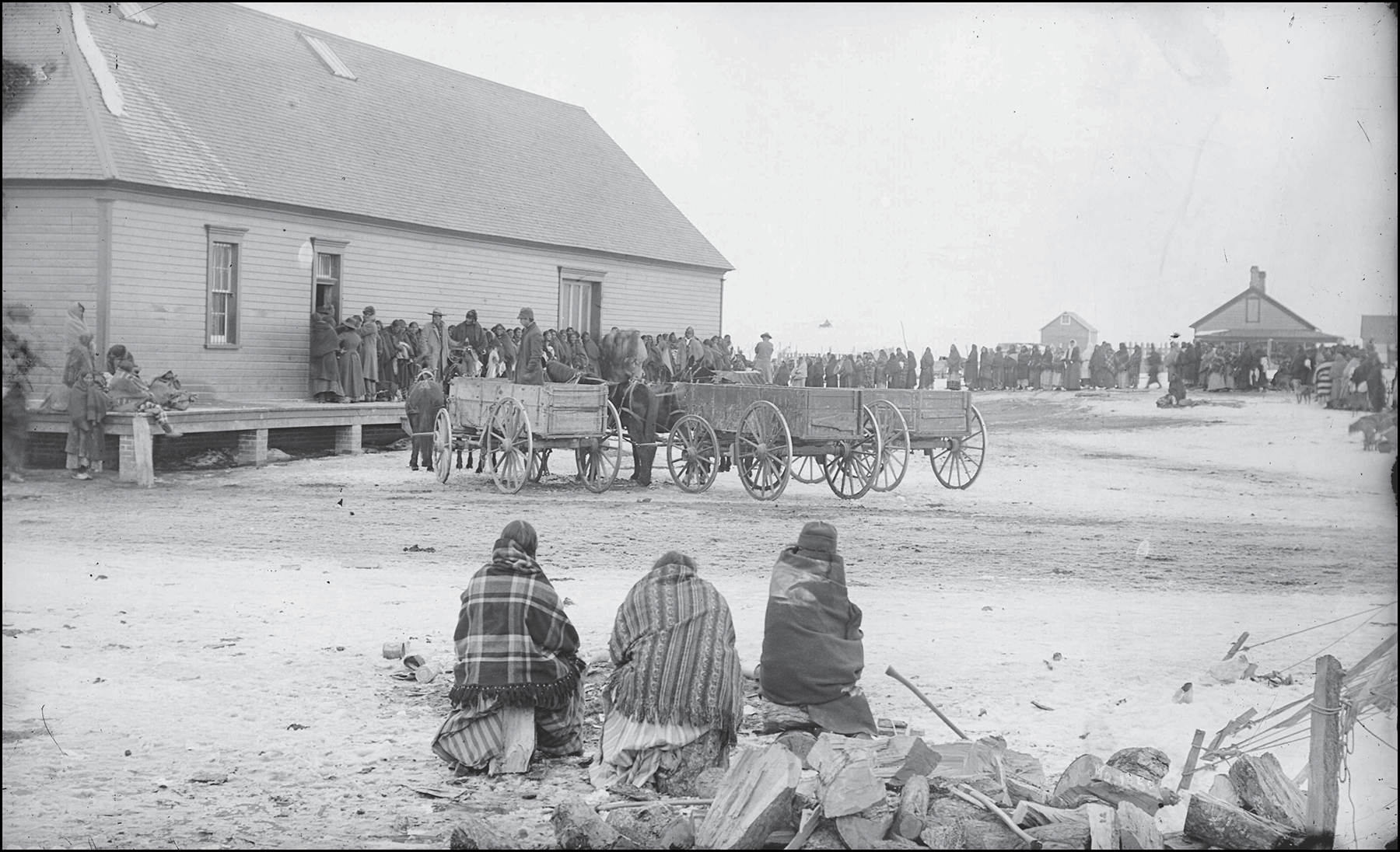

The desperation that would drive believers to the circle was not yet a foregone conclusion. In and of themselves, reservations did not spell the end of all the old ways. Lakotas ventured away from the Great Sioux Reservation to hunt as late as 1876, and hunting, gathering, and nomadic movement continued even within some reservation boundaries into the 1880s. But the new economy that now characterized the Plains soon strangled whatever was left of Indian autonomy. Farmers broke the short-grass plains with new steel plows to replace the buffalo grass with corn and wheat, and cattle supplanted bison as the region’s most populous large animal. Having lost much of their onetime realm to the new state of Nebraska in 1866, Lakotas lost most of the rest of their lands in 1889 when they were incorporated into the states of Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota, and, of course, South Dakota, where most Lakotas were confined to reservations. Reduced to fewer than 25,000 people, they were the most numerous of the Plains tribes, and yet they were a tiny community of Indians in what had become a settler country. In 1890 the census recorded 300,000 non-Indians in South Dakota, and over 1 million in Nebraska. Well over $100 million worth of cattle, horses, pigs, sheep, and mules grazed the old bison range in those two states alone.12

On the warmer central and southern plains, in the onetime homelands of the Arapaho, Cheyenne, Kiowa, and Comanche, farm and ranch settlement proceeded even faster than in Nebraska and the Dakotas. By 1890, Colorado, Kansas, and Texas were even more populous and had more farms than South Dakota and Nebraska, and almost all Indians who had resided there had been transported to Oklahoma. Hemmed into their reservations, the best land now firmly in the hands of settlers who grossly outnumbered them, Indians had long since given up armed resistance. The Plains Indian Wars were over.13

But settlers were not done taking Indian land. Between 1880 and 1890, Americans responded to drought and the stuttering economy of grain and glut with a renewed, highly energetic white invasion of remaining Indian lands second only to the invasion that had forced them onto reservations in the first place. Plains farmers pumped billions of bushels of wheat and corn into world markets. By the late 1880s, as drought gripped the Plains, crop prices plummeted, leaving many farmers unable to pay their debts. Kansas, South Dakota, and Nebraska farmers flocked to the Farmers’ Alliance, a Populist political movement that sought new forms of government intervention to save them from crushing market and climatic forces.14

In these conditions, the last thing farmers needed was more farms to produce more grain and drive prices even lower. But the millenarian belief in farm creation as the advancement of civilization inspired angry Populists to demand that still more land be opened to white settlement. Passage of the Dawes Act in 1887 gave Congress and the White House the authority to force Indians to sell most of their reservations (retaining 160 acres for each head of household and smaller amounts for dependent children), and settlers on the Plains urged authorities to do just that. Thus, the Populist movement lent its energies to the destruction of the Great Sioux Reservation and the Indian reservations in Oklahoma, forcing on Indians massive land transfers and renewing settler incursions—“land rushes”—onto reservations that only a few years before had been promised as exclusive Indian land. After the first Oklahoma land rush in 1889, the territory was settled at least as rapidly as had happened in the Dakotas. The 1890 census recorded over 8,800 farms in Oklahoma, comprising over 1.5 million acres, valued at $8.5 million. In 1880, there had been less than 300 miles of railroad in Oklahoma; by 1890, over 1,200 miles of track had been laid.15

And still the Americans wanted more. In 1888 Congress sent commissioners west to demand massive land sales by Lakotas, and in 1889 it created the Jerome Commission to arrange the purchase of land from Oklahoma tribes, including the Southern Arapahos. These were one-sided negotiations in which commissioners held all the cards. Indians knew that if they did not agree to sell their land, the Americans could just take it. Rumors of a messiah in the West were thus circulating among Plains Indians at the very moment they were forced to confront new, enormous land grabs.16

Across Oklahoma and the entire Plains, new physical boundaries demarcated a radical reorganization of space. In 1874, the Glidden Manufacturing Company of DeKalb, Illinois, became the first producer of barbed wire. Despite the constraints of manufacturing by hand, it sold a remarkable 10,000 pounds of wire that year. As western farmers and ranchers realized the utility of “bob wire” for managing the movements of animals and people on the almost treeless (and therefore woodless and fenceless) plains, sales skyrocketed. In 1879 alone, the now fully mechanized company produced over 50 million pounds of wire.17

On their reservations, Lakotas, Cheyennes, Arapahos, and other Indians were isolated in a landscape that was deeply familiar but from which they were also increasingly estranged. Some Indians who traveled between the Northern and Southern Plains remarked that the open prairie they had crossed only fifteen years before was “now thickly settled, covered with wire fences, and has railroads in all directions.”18

At the same time, across the entire plains, north and south, overstocking of the range had shattered the grassland. Cattle were probably never as numerous there as bison, but they nonetheless exacted a heavy toll, partly because of their grazing habits. Because bison eat almost entirely grass and ignore certain kinds of forbs and sedges, other animals can flourish amid even large bison herds. Cattle, in contrast, graze a wider array of plant species than bison, demolishing grass, forbs, and sedges alike. Bison and cattle both seek river valleys for water and shelter, but bison tend to spread out, away from riverbanks, to graze. Cattle herds congregate in much greater numbers along river bottoms and are reluctant to move away from there even when the grass is gone. In the 1880s, they trampled riparian zones, grazed meadows bare, and stripped riparian forests of their bark until all that remained of many a prairie stream was a mud flat punctuated with dead trees. As cattle replaced bison, they joined a host of other forces reshaping the Great Plains, including relentless hunting by millions of white settlers. In the skies and on the ground, not only buffalo but dozens of species that had cohabited with the great herds all but disappeared. The call of the curlew and the bugling of elk gave way in most places to the lowing of cattle—or silence.19

Confined within reservation boundaries, Plains Indian people no longer migrated between river valleys, but to the abstracted river of money: the hunt for game and plants gave way to the hunt for dollars and work. In itself, this was not an insurmountable challenge. Lakotas, Arapahos, and other Plains Indians had a centuries-long tradition not only as independent hunters but as sellers of pemmican and furs to white and Indian merchants. They were no strangers to markets.

But by the 1880s, when Paiutes in Nevada were selling fish, pine nuts, and firewood in settler towns and cities, Plains Indians no longer had much that white buyers wanted—except land. Paiutes could sell their own labor, but almost no wage work was available to the Western Sioux, Southern Arapahos, and other Plains Indians. Their reservations remained remote from the cities, towns, and farms where work might have been available. Even when settlements were not out of reach, the government banned Plains Indians from leaving reservations without permission—which was seldom given.

Lakotas and most other Plains Indians thus had few sources of money. For paid work, they turned to the Indian agency, which employed them in freighting, road building, woodcutting, police service, and the occasional construction of schools, churches, and other buildings. But at best, the reservations generated only a few dozen such jobs. Some Oglala Lakotas, Pawnees, and a few others found employment in Wild West shows. At Pine Ridge, these shows employed far more Lakotas than the agency did: in 1889, 200 Lakota men (and still more women and children in their families) departed the reservation to work with show companies, an industry that paid them tens of thousands of dollars. But only a tiny proportion of all Indians could work in such entertainments.20

The scarcity of work led to desperate responses when jobs did become available. By the early 1880s, men flocked to building sites in the Southern Cheyenne camps at Darlington, in Indian Territory, in such numbers that supervisors had to monitor the stone-hauling, brick-making, and lime-burning operations to ensure that all the men on the job had in fact been hired. By the time Jack Wilson’s prophecies began to emanate from the Walker River country in 1889, Northern Arapahos at Wind River Reservation were cutting wood and hay, hauling coal, digging irrigation ditches for the government, and scrambling for practically any paying job.21

As early as the late 1870s and continuing through the 1890s, Indian men acquired wagons and teams and hauled millions of pounds of goods at Lakota reservations as well as on the Southern Cheyenne–Southern Arapaho reservation in Oklahoma and on the Northern Cheyenne and Crow reservations in Montana. Among the men who undertook the freighting business was Short Bull, who was driving shipments between Valentine, Nebraska, and the Rosebud Agency in South Dakota by 1889. “The Indians make good freighters,” observed the agent at Pine Ridge in 1888. “They like the business and apparently never tire of it.”22

In all these places, Indian entrepreneurs branched out in a variety of ways to make a little money. By 1890, some at Pine Ridge and elsewhere were producing goods for a nascent craft industry, selling moccasins and beadwork to traders who supplied a growing market for Indian curios. Others scrambled to sell other goods. In 1886, as eastern manufacturers bought up buffalo bones and ground them into fertilizer, Brule Lakotas at Rosebud Reservation gathered up 330 tons of buffalo bones and sold them for $8 a ton. Others tried to charge whites for using Indian land. In Oklahoma, Southern Arapahos launched an ultimately unsuccessful effort to tax the aggressive Texas cattle outfits that trespassed on their reservation. Subsequent agreements to lease grassland were also mostly unsuccessful; American cattlemen refused to hire Indians as cowboys and drove small Arapaho herds (from the handful of Indians who acquired cattle in the 1880s) away with their own.23

To compensate for the lack of money, some Plains Indians—like their Paiute contemporaries in Nevada—made serious, often enthusiastic efforts at farming, in imitation of the comparatively wealthy and powerful Americans nearby. At Wind River Reservation, Northern Arapahos cut irrigation ditches with a shared plow in the early 1880s. By 1886, Northern Arapaho chiefs in Wyoming and Southern Arapaho chiefs in Oklahoma oversaw large fields and gardens where their families and followers produced hay for market and food for the community. Lakota teamsters pooled their earnings to buy communal farm implements at Rosebud and also at Pine Ridge, where Indian farmers grew 21,000 bushels of corn and 6,000 bushels of potatoes in 1888. Even the Hunkpapa Lakota leader Sitting Bull, who was widely considered a staunch opponent of farming, made at least some of his living on the reservation as most Lakotas did—through a mix of rations, produce from his home garden, and income from raising cattle, hay, and oats. In Oklahoma, aspiring Arapaho and Cheyenne cultivators, in the absence of plows and harrows, chopped through the prairie with hand axes and worked the soil with their fingers.24

Across the Plains, as Indian children born in the reservation era matured, Indians grew ever more oriented toward wage work and farming. Compelled by government agents to attend reservation day schools or sent away to government boarding schools like the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, Indian children received an education that was overwhelmingly vocational. Boys’ instruction emphasized tasks like baking, carpentry, and livestock management, and girls learned laundry, sewing, and cooking. They also learned about agriculture, their education thoroughly imbued with the American veneration of farming as the bulwark of democracy, the guarantor of independence, and the source of wealth and respectability.25

FIGURE 6.2. Lakota man and child at home on Rosebud Reservation, ca. 1891. By the time the Ghost Dance arrived, most Lakotas had built log homes, and many were attempting to farm. Note the hoes on the roof. Nebraska State Historical Society, RG2969-PH-2–206.

But with work scarce and seasonal and farms increasingly unreliable in the drying climate, most Indians on the Plains turned more and more often to rations; that dependency allowed American authorities routinely to deploy their immense power—to withhold rations to compel “progressive” behavior—to starve Indians and crush their resistance. Where once Indians were self-sustaining, now they depended on distant flour mills, canneries, and plantations for their sustenance. Like laborers in distant cities, Indians were among the first people in the world to depend on industrialized food for their survival.

Rations were not welfare, however; they were written into agreements with the US government as payment for land ceded by Indians. However unfair and inadequate, they were the product of a market transaction between Indians and Americans. They were also modern commodities, paid for by the US Congress and delivered to Indian reservations by private contractors. These meager allotments of clothing, flour, beef, corn, beans, coffee, and sugar, together with a few farm implements, were all that kept Indians from freezing and starving to death; after the ration cuts of 1889, they did not even accomplish that much. Lakotas especially could see the impact of poor food on their ailing bodies. “Physically, they are wrecks of what they once were,” observed the teacher Elaine Goodale. Southern Arapahos, too, saw their beef ration cut in half in 1889. Forced to create new recipes from poverty rations, Lakotas, Arapahos, and other Plains Indians fried flour in lard to produce what became known as fry bread, a food that fills stomachs but has little nutritional value. It became a staple of reservations, a potent sign of the transformation of Indian villages into market-dependent communities with little or no money.26

FIGURE 6.3. Lining up for rations at Pine Ridge, 1891. Denver Public Library, Western History Collection, X-31388.

In the drought that wracked Nevada in 1888–1889, Jack Wilson awoke from his trance journeys across the Milky Way with ice in his hand. In 1890, Lakotas would testify that some Ghost Dancers returned from heaven clutching buffalo meat.27

LIKE ALL PEOPLES, INDIANS SAW THEIR SPIRITUAL CONDITION as one explanation for their economic and political hardships, and many sought religious solutions. Some turned to customary ritual with increased fervor, praying to renew the earth and revive their old autonomy. The Lakota word connoting the sacred or the holy, wakan, refers more broadly to spirit power, or the sources of spiritual power, that surrounded all Lakotas at all times. Collectively, these were known as Wakan Tanka, the Great Mysteries. Now holy men like Short Bull led devoted followers in rededicating themselves to ritual observance and the teachings of White Buffalo Calf Woman, a powerful spirit being who had arrived among the people in the distant past and presented them with the Sacred Pipe, which became a key element of Lakota ritual. Along with this gift, White Buffalo Calf Woman had advised the people to learn the seven major Lakota ceremonies that subsequently were given them to ensure growth and prosperity.28

The Sun Dance was the most prominent and popular of these ceremonies—and the primary communal religious gathering by the nineteenth century. In the dance, individual dancers made offerings to spirits, most notably Wi, the Sun, the Revered One, also called Our Father, patron of the four great Lakota virtues of bravery, fortitude, generosity, and fidelity. Other spirits manifested during the dance as well, including Grandfather Buffalo, who was essential to virtually every aspect of Lakota life. Grandfather Buffalo was the spirit of the Earth, the force from whom all buffalo came into this world, the patron of domestic affairs, ceremonies, and sexual relations, and as the chief of all animals, the one who controlled the chase. He presided over the Sun Dance and received many prayers and sacrifices.29

Lakotas propitiated these and other spirits at summer Sun Dance gatherings through sacrifices made in the space between a circular sacred arbor and a tree cut down and re-erected at the center (the tree marking the center of the world, and its axis). Offerings to the spirits might include only fasting and dancing, but the Sun Dance was famous (or notorious) among Americans for another kind of offering. A holy man would pierce the chests or back muscles of a select group of pledgers, who had specially prepared for the event, using an awl connected by a rawhide thong to the central tree, to a buffalo skull, or even to posts erected near the tree. With skewers in their chests or backs, and blood streaming down in sacrifice to Wi, all of the pledgers stared at the sun and danced until they tore themselves free. Though piercing was restricted to men, women and children could join the devotions by dancing and staring at the sun. With these personal sacrifices, Lakotas implored the spirits to take pity on them and fulfill their requests for success in hunting and war, or offered thanks for the recovery of family members from illness or other misfortune.30

Lakotas flocked to the Sun Dance in the 1880s, when they were still new to reservation life and the future seemed hopeless to many. The continuing popularity of the ritual and participants’ energy and enthusiasm may partly explain why it attracted so much government hostility. Soon, however, the ceremony and the holy men who led it fell victim to assimilation policy. Missionaries and other ardent Christians tended to see holy men and all ceremonial leaders as competition for Indian souls and as the devil’s minions, and Short Bull and others found themselves in confrontations with them almost from the minute they took up reservation life. In 1879, the agent at Rosebud announced a ban on the Sun Dance. Short Bull joined with another man named Two Heart to lead a group of Lakota dissidents north in an effort to reach Sitting Bull’s camp in Canada, where they could worship in peace. But the army caught them, and by the fall they were back at Rosebud.31

In his campaign against the Sun Dance, the Rosebud agent was operating only on his own authority. But a broader ban soon followed. In 1882, Secretary of the Interior Henry Teller explicitly banned “the old heathenish dances” among all Indians and instructed Indian agents to compel holy men to “discontinue their practices.” Teller, like most Indian agents and many other Americans, saw holy men as frauds who kept Indian children from school, manipulated Indian superstitions by employing “various artifices and devices to keep the people under their influence,” and persisted in “using their conjurers’ arts to prevent the people from abandoning their heathenish rites and customs.” Under his new guidelines, agents among the Lakotas initiated a vigorous campaign against holy men, refusing rations to people who participated in the Sun Dance and threatening them with starvation. They ordered the Indian police—handpicked and commanded by the agents—to raid Sun Dance gatherings and harass holy men. When the police met resistance, they assaulted leading holy men and dancers and dragged them to jail. In 1881, the agent at Crow Creek ordered police to put a stop to “a barbarous festival” featuring “an immoral dance”—probably a Sun Dance. The officers shut down the ritual, in the words of the agent, with “a characteristic ‘knock down and drag out’ of the principal offenders.”32

Far more than the ritual itself was lost in the Sun Dance ban. The Sun Dance expressed and maintained community well-being in a host of ways, and the ban weakened holy men as a tribal institution. Without property sacrifices—gifts from pledgers who needed holy men to serve as their mentors—their wealth declined.

More broadly, the ban ramped up social friction. A Sun Dance was usually accompanied by a large-scale transfer of goods from richer Lakotas to poorer members of the tribe. Each year’s dance was sponsored by a person who had taken a vow to Wi to host the ceremony, often in return for deliverance from danger or illness. As the date for the dance approached, the sponsor sacrificed all of his property by surrendering it to the needy. Other wealthy people also gave generously to the poor as the ceremony progressed. Each gift of horses, buffalo robes, or richly beaded cloth from rich to poor encouraged the spirits to be similarly kind to Lakotas, or as Lakotas put it, “to take pity” on them. Thus, the “vast amount” of wealth that changed hands during the ritual eased tensions among Lakotas and bound them together in reciprocal obligation.33

The dance also created a space for other functions that might or might not have been related to spiritual matters. Many holy men and women were among the large, convivial crowd that massed around the sacred arbor, and they took the opportunity to see to the people’s spiritual well-being through a wide array of other rituals and ceremonies. Ailments were healed, and seekers took up vision quests—solitary ventures to remote places for fasting, in hopes of an encounter with spirits—with help from holy men. The community also tended to its politics: new chiefs were elevated, new police or camp marshals were selected, and men’s societies and ceremonial organizations were convened. In its ritual and social expressions, the Sun Dance regenerated the community.34

For Lakotas and others, the Sun Dance—always the most heavily attended of their communal events—was a spiritual request for buffalo and generalized abundance. As bison receded and the old ecology and economy of the Plains collapsed, Indians performed the ritual with ever greater intensity. In the decade before Wovoka’s prophecies began circulating, the gatherings were vast. In 1880, the ceremonial circle of the Oglala Sun Dance contained 700 lodges and was six miles in circumference. In 1882, when the Sun Dance convened at Rosebud (probably with Short Bull in attendance), the camp was three-quarters of a mile in diameter as 9,000 people—almost one-third of the Lakotas on earth—assembled for the devotions. After the ban was announced the following year, the next public Sun Dance would not be held until 1951.35

Meanwhile, on the Southern Plains the ban on the Sun Dance was less rigorously enforced. The Arapaho Sun Dance, known as the Offerings Lodge, maintained a public face far longer than the Lakota Sun Dance and was performed openly as late as 1902.36 A number of factors kept religious conflicts from becoming as severe in the south as they already were in the north. Agents watched Lakotas closely because there were 18,000 of them—substantially more than for any other Plains tribe. By contrast, Indian nations in Oklahoma were smaller. There were only 1,100 Southern Arapahos in 1890, and the combined population of the Southern Cheyenne–Southern Arapaho reservation was only about 3,500. There were other Indian tribes in Oklahoma, and eventually, though they would take some time to form, multi-tribal coalitions would emerge to resist ceremonial proscriptions. These differences in population tended to make religious arguments with the government much louder in the north than in the south. Self-conscious, perhaps, about their small numbers, Southern Arapahos became adept negotiators. A large proportion of them acceded to agency demands to send their children to school, for example, perhaps as a strategy to maintain their religious ceremonies. Lakota responses to agency demands tended to be far more variable and, at times, contentious.

For their part, the Southern Arapaho agents in these years appear to have adopted a policy of gradually phasing out the old religion rather than abolishing it all at once. Their relative passivity toward Southern Arapahos probably stemmed in part from their preoccupation with Southern Cheyennes. The two tribes shared one reservation and one agent, whose attention well into the 1880s was focused on confrontations with mostly Southern Cheyenne men who threatened raids and other hostilities off the reservation. The agents seem to have remained almost ambivalent about the Offerings Lodge. When the agent D. B. Dyer attended the ceremony in 1885, he proclaimed the dancers’ intense devotion “worthy of a better religion” but also acknowledged the “indomitable heroism” of their sacrifice.37

Even such limited tolerance as this was in short supply elsewhere in Oklahoma. In 1887, the Kiowa agent authorized a Sun Dance without piercing and “with a distinct understanding that it should be the last.” When Kiowas attempted to hold another Sun Dance in 1890, they were intimidated out of it by their agent’s hostility and rumors of an attack by soldiers from nearby Fort Sill. In Darlington, the forebearance of the agent did not last. Although Southern Arapahos were still hosting the Offerings Lodge in 1902, it soon vanished, not to reappear until 2006. In these ways, the reservation period initiated severe persecution of ceremonies across the entire Plains. Like the Offerings Lodge of the Arapaho and the Sun Dance of the Lakota, the religious traditions of other tribes, from the Comanches of Oklahoma to the Blackfeet of Montana, soon became targets for eradication.38

Even when a celebration of the Sun Dance or another ceremony occasionally slipped through the wall of religious suppression, the poverty of reservation life militated against the old religions, all of which required property sacrifices that fewer and fewer Indians could muster. For example, among Southern Arapahos, the Offerings Lodge had to be sponsored by a married couple who had achieved seniority in a hierarchical system of sacred societies, or “medicine lodges.” Staging the Offerings Lodge required the cooperation of the entire medicine lodge hierarchy, which itself undergirded the social order and depended on chains of property sacrifice. Without a steady supply of horses, hides, and other goods, the stream of property sacrifices proved ever harder to sustain.39

EVEN THOUGH SOUTHERN ARAPAHOS PROVED BETTER ABLE THAN many others to withstand the attack on the Sun Dance, the ban on Indian ceremonies and the persecution of the holy men and women who led them demoralized Plains societies everywhere. Among Lakotas, such measures threatened to sever the connections between powerful spirits and the Lakota community. We may assume that Short Bull, like other holy men, was still leading the Sun Dance, or trying to, after the ban was imposed, directing the ritual in secret. It is impossible to tell how successful such events were. However many people the ceremony drew under these conditions, it was no longer a communal festival. For the first time in memory there were compelling reasons not to attend, for doing so earned the ire of officials and police, who confiscated the property and rations of those who danced. The ban on the Sun Dance thus brought fragmentation, alienation, and spiritual isolation.

The proscription on piercing and devotion not only deprived holy men of an important arena for ministering to their people but impoverished them by halting the payments for their mentorship. For all other Indians, the ban was an abject disaster. In old times, a man with sufficient means could pray for the salvation of his loved ones from hunger, sickness, or the hatred of their enemies by vowing to perform the Sun Dance, thus invoking the aid of the Sun and Wakan Tanka. But with the ban on the ritual, such vows could not be fulfilled. Agents were familiar with the problem, but simply—devastatingly—ordered their charges not to make any more vows.40

As the desperation of Lakotas mounted at the close of the 1880s, holy men like Short Bull looked for a way to rebalance relationships with Wakan Tanka, to set the world to rights and restore the freedom and well-being of their people. Bison eradication had uprooted and deracinated a religion that honored and requested assistance from Sun, Grandfather Buffalo, and the rest of creation. The spirits still came to seekers; in the Sun Dance circle and on vision quests, Lakotas still encountered Buffalo, Bear, Elk, Badger, and others. But the near-extinction of animals, along with their vanishing autonomy and mounting poverty, left Lakotas asking which ritual measures could restore the balance of forces and regain for them the pity of spirits who not so long ago had made them the most powerful Indians on the Northern Plains.

In this context of a beleaguered old religion and profound economic and social crises, new rites and religions beckoned, and the decades leading up to the Ghost Dance were a period of pronounced religious turbulence. A movement based on a curing ceremony known as the Midewiwin, or Medicine Dance, had burned through the Great Lakes region in the late 1700s, and as the United States pushed Kickapoos, Potowatomis, and Sac and Foxes from the Great Lakes to the Plains, they carried the movement to Iowas, Dakotas, Poncas, and other Plains peoples. Sometime before 1860, another shamanistic movement known as the Grass Dance spread from the Omahas westward across the Plains. The Grass Dance eventually lost most of its religious features, but elements of it were combined with the Medicine Dance to create still another religious movement, the Dream Dance, which first took hold among the Santee Sioux in Minnesota in the late 1870s. Seeking goodwill, health, earthly renewal, and the return of the old ways through prayer and singing, the Dream Dance spread south, reaching tribes in Kansas and Oklahoma by the 1880s.41

Oklahoma in particular proved a hotbed of revivalism and millennialism well before Wovoka’s prophecies arrived. Spiritual longing arose among its thousands of impoverished Indians, almost all of them relocated from other regions or confined to shattered fragments of former homelands. Ranks of shamans, seers, prophets, and evangelists emerged, heralding new intertribal religious movements. Some of these arose in defense of traditional religions. Others promised to restore bison and the old ways. Still others proposed banishing white people from the earth. As early as 1881, Keeps-His-Name-Always, a young Kiowa, began to prophesy the return of the bison and the destruction of settlers and instructed followers in sacred prayer and ritual to fulfill the prophecy. The prophet died in 1882, but in 1887 another Kiowa, In-the-Middle, claiming to be his heir, revived the prophecy. In-the-Middle promised that the day was fast approaching when white people would be eliminated and the bison would return, and Kiowas flocked to his camp on Elk Creek to await the happy hour. When the prophecy failed, they returned to their homes, deeply disappointed. Two years later, in 1889, In-the-Middle hailed news of the Ghost Dance prophecy as a fulfillment of his own visions.42

The Kiowa prophecies no doubt found their way across Oklahoma to the Southern Cheyenne–Southern Arapaho reservation, where the Ghost Dance was soon to blossom, for in spite of agents’ attempts to limit intertribal contact, Indians in western Oklahoma frequently socialized and often intermarried. Thus, between the Dream Dance and the Kiowa prophecies, religions that promised the return of the old ways and the renewal of the earth had become a Great Plains tradition well before Wovoka’s teachings arrived.

To be sure, not all of the emergent movements were as apocalyptic as the Kiowa prophecies. Another set of practices and beliefs that had a far wider impact emerged about the same time. When authorities became aware of the Peyote Religion a decade or so later, they spoke of peyote as an hallucinogen. Believers, even now, refer to peyote as a sacred herb, a living spirit, even a part of God, who brings enlightenment, teaches righteous living, and ensures well-being.43

The Peyote Religion addressed the problem of reservation confinement and surveillance by allowing believers access to spirit power even when they could not move beyond reservation boundaries and remained under the nominal control of the agent. The key element in the Peyote Religion was the flower of the peyote cactus, Lophophora williamsii, a plant native to northern Mexico and southern Texas and for millennia widely used as a ritual cure in Mexico. Peyote came to Oklahoma with those Indians who had made raids into Mexico or lived there prior to the reservation period, primarily the Comanche, Kiowa, and Kiowa Apaches, all of whom had become familiar with the powers of peyote to relieve pain and provide powerful visions. Peyote served spiritual needs specifically brought on by the reservation era. Men of Plains societies struggled to pursue vision quests at sacred sites because many of them, now beyond reservation borders and bounded in barbed wire, were off limits to Indians and dangerous to visit. Peyote empowered believers to achieve a visionary state in a short period of time, in a ceremony held inside a lodge and easily hidden from agents, obviating the need to venture far afield or risk injury or arrest for leaving the reservation in a days-long, solitary ordeal.44

Peyote use had become institutionalized in Indian Territory by the early 1880s in a standard ritual pioneered by Quanah Parker, the last free war chief of the Comanches and the leading Comanche chief in the reservation period. Central to the Peyote Religion were all-night ceremonies involving small groups of people who gathered in a tipi to sing, eat peyote, and pray, often to Jesus. In the words of one of its preeminent historians, the ceremony had “overtones of Christianity, but [was] so different from all Christian sects that it would provoke them all to do their best to eradicate it.”45

Given the enthusiasm of evangelists and the proximity of tribes in the increasingly crowded Indian Territory, it did not take long for peyote devotions to spread. Quanah Parker himself led peyote meetings among the Southern Arapaho in 1884. Soon thereafter, a twenty-two-year-old Arapaho and former Carlisle student named Jock Bull Bear began learning the ritual from Parker. Meanwhile, a Southern Arapaho man, Medicine Bird, studied the ritual with Plains Apaches and in 1888 innovated a version that became widely accepted in Arapaho communities.46

By the 1880s, then, Plains religious life was infused with a broad range of traditional and new beliefs, from apocalypticism to the more contemplative and ethical teachings of the Peyote Religion.

As Christian missionaries increasingly intruded into this landscape that echoed with teachings old and new, Indian religions certainly grappled with the meanings of Christianity too. In 1869—the very moment when many of the Plains tribes began seriously to consider moving to reservations—President Ulysses S. Grant had articulated his Peace Policy, which placed reservations in the hands of Christian churches. Under the policy, any church that did the work of running a reservation gained exclusive control over it, including the power to select teachers for reservation schools, bar competing churches from the reservation, and appoint agents (who were themselves missionaries). The Peace Policy was applied in Nevada as well, but missionaries there paid little attention to Northern Paiutes, most of whom did not live on reservations anyway.47

Indians on the Plains were more systematically confined to reservations than Indians in the Great Basin, and Plains reservations were supervised primarily by Protestant missionaries for over a decade after 1869. Thus, evangelical Christianity had a presence in and near Plains Indian communities that it never had in the Great Basin (except in the few places where Mormon missionaries were present). Under this policy, the first agents appointed for the Southern Cheyenne–Southern Arapaho reservation, in 1870, were two devout Quakers, Brinton Darlington and John D. Miles.

Both men dedicated their missionary efforts primarily to the Southern Cheyenne. Ten years later, in 1880, missionaries from the General Conference of Mennonites began preaching to Southern Arapahos at a mission station at Shelly, on the Washita River, and opened schools for them at Darlington and Cantonment and the Indian Industrial School in Kansas. Among neighboring tribes, Southern Methodists and Baptists had taken up residence by the time Wovoka’s prophecies took hold.48

All these efforts met mixed results. Mennonites did not achieve their first convert until 1888, and as late as 1900 only about forty Arapahos had declared their faith as Mennonites. Southern Methodists gained a few prominent Kiowa converts in 1888, but had little success in the years following. And yet, even as most Indians proved reluctant to take up Christianity, some seized opportunities to explore it on their own terms. Four Southern Plains warriors, held as prisoners after the Red River War of 1874–1875, volunteered for a year of Christian study in New York, and at least one preached the gospel on his return.49

Such stories suggest the powerful ambivalence of Indian communities toward New Testament instruction. On the one hand, many Indians on the Plains were interested in Christian teaching and many experimented with Christian belief and practice. Their reasons were as diverse as the people themselves. Some were genuinely moved by Christian preaching and faith. Some solicited missionaries to serve as allies in their negotiations with the government and provide instruction in English and literacy, key tools for negotiating Indian rights in the reservation era. Many Indians believed that Christianity undergirded the military and economic success of the American people (a belief they shared with most Americans). Since Americans possessed great wealth and ingenuity and defeated one Indian enemy after another, some Cheyennes, Arapahos, Lakotas, and others came to regard the spirit powers of Americans as formidable and potentially worth adopting—or adapting—for their own uses. Partly for such reasons, white and Indian missionaries across the Plains found audiences, however small, of Indian peoples who were often willing to engage and even affiliate with Christian churches, while retaining ties to their old religions.

Thus, even where Christianity did not find ready converts it had influence. And yet, as the growth of the Peyote Religion suggests, even some of those most willing to embrace certain Christian ideals rejected the straitjacket of Victorian Protestantism, preferring new religious forms that combined Indian traditions with new beliefs. In part, such efforts were grounded in the continuing fight against assimilation. All Indians wanted health and prosperity and success in the reservation era, but on terms that were distinctly Indian. In the fight to preserve Indian ways, religion moved to the fore as a furious battleground of ideas and practices, as exemplified in the growing fight over the Peyote Religion and other forms of Indian religiosity.

THIS PHENOMENON OF SIMULTANEOUS ENTHUSIASM FOR RELIGIOUS innovation and resistance to assimilation was also common on the Northern Plains, but with key differences. For one thing, the Peyote Religion did not come north for some time. Also, in the years leading up to the Ghost Dance, Lakotas faced a more concerted advance by missionaries, an onslaught of doctrinaire Christianity that seemed to underscore and backstop the economic and political revolutions sweeping the Plains.

At first, Christianity made slow progress among the Western Sioux. In 1871, Oglalas at the Red Cloud Agency received J. W. Wham, Episcopalian, as their first agent, and Congregationalists established a mission at Cheyenne River the following year. Until later in the decade, however, most Lakotas remained far to the north, well away from agents, missionaries, and even the Great Sioux Reservation, and the churches had limited influence. But once all Indians had been confined to the reservation, Christian missionaries consolidated their authority. Catholics asserted control of Standing Rock in 1876. At Rosebud, Cheyenne River, and Pine Ridge, Episcopalians seized command of preaching, schools, and reservation agencies by the late 1870s.50

Although many of the missionaries were forceful in their demands that Indians attend church and receive baptism, conversions and church membership lagged among Lakotas until the early 1880s. At that point, Sitting Bull’s people, the last of the Lakotas to refuse to move to reservations, finally returned from Canada. At about the same time, the Peace Policy ended; agencies were returned to government control, with agents appointed by the party that won the White House. With reservations no longer allocated to particular churches, and with churches no longer able to exclude others from the reservations they occupied, the Christian denominations began to compete with one another for Indian converts. The result was a religious free-for-all as Catholics, Episcopalians, Presbyterians, and Congregationalists vied for Indian hearts, urging them not only to abandon “heathenish practices” but also to avoid competing churches. From 1881 to 1890, the number of churches at Lakota agencies mushroomed from six to thirty-one, and the number of missionaries from six to fifty-four.51

Significantly, these churches also looked to Indian converts to evangelize Lakotas. Catholics appointed Lakota catechists. Yankton Dakotas, eastern relatives of the Western Sioux, proved particularly influential in spreading the Christian gospels. The Yanktons lost their old homelands in Iowa and eastern Dakota Territory by 1858, when they took up a reservation on the Missouri River at today’s Yankton, South Dakota, some 200 miles east of the Lakotas. Congregationalist missionaries among them appointed Dakota preachers—“lay ministers” like the influential Elias Gilbert—to proselytize among their Lakota kinsmen. But an even more influential group of Episcopalian Dakotas soon took posts among the Western Sioux.52

In 1870, Tipi Sapa, the son of Chief Saswe of the Yankton Dakotas, was converted to Christianity by Episcopalian missionaries and took the name Philip J. Deloria. Subsequently, he studied for the ministry at Nebraska College and in Minnesota. By 1885, with the Peace Policy abandoned and missionaries from competing churches sharing reservations, Deloria had become the Episcopal minister at the Standing Rock Agency, where Sitting Bull’s people had settled. The Dakota and Lakota languages are related and mutually intelligible; though he preached in Dakota, Deloria’s message resonated with his Lakota congregation.

Another mixed-blood Dakota Episcopalian, Charles S. Cook, studied in Nebraska and at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, before becoming deacon at the Pine Ridge Agency in 1885, and then priest in 1886.

Finally, a third convert, Ojan, moved to Pine Ridge, where he became a schoolteacher. The son of a Dakota chief named Medicine Cow, Ojan had taken the name William T. Selwyn and also studied in the East. As we shall see, he never rose in the church, but his closeness to the institution, his powerful backers in the East, and his education would give him a large and unfortunate influence on American perceptions of the Ghost Dance.53

Meanwhile, whether because so many missionaries were preaching in the Dakota language or for some other reason, in the 1880s Lakotas suddenly became more willing than most Cheyennes and Arapahos to join churches. Indeed, an especially salient feature of this region where the Ghost Dance fervor became pronounced was that so many Lakotas had joined Christian churches by the time it arrived that a leading Lakota chief named Big Road would relate to a journalist, “Most of the Indians here belong to the church.” If church attendance was not quite what he claimed, the numbers suggest that Christianity did have a strong hold by 1890. Beginning with only a few hundred Lakota Christians in 1880, church officials claimed by 1889 that 4,757 souls among the 18,000 Western Sioux were Christians. Of the 5,611 Lakotas at Pine Ridge, almost half—2,213—were said to be attending church regularly, and the other Sioux reservations reported similar growth in church attendance.54

With good reason, scholars have been cautious with these figures and sometimes dismissed them as unreliable. Indian agents and missionaries often worked in concert, with agents refusing rations to those who did not go to church. Even for those who went voluntarily, baptism and enthusiastic devotion did not always signify conventional conversion. Lakotas, like other Indians, adhered to few orthodoxies in spiritual matters. The central requirement of Lakota religion was (and is) that every individual access the Great Mysteries, Wakan Tanka, by persuading the spirits to take pity on her or him. In this universe, rituals are carefully monitored and guided by holy men, but new beliefs may be incorporated alongside traditional beliefs if found to be helpful and consistent. On the reservation, Lakotas experimented with Christian ideas and practices in an effort to acquire the power of their conquerors without abandoning the old religion. So it was that even seemingly devout church members practiced elements of the old religion, from vision quests to healing rituals, leading missionaries to express frustration at the absence of what they considered “real” Christianity among converts.55

Although the number of Sioux converts should not be accepted without question, neither should it be rejected outright. The documentary record contains too many accounts of dedicated Lakota catechists and deacons, late-night meetings of the Brothers of Saint Andrew and the Sisters of Saint Mary, and donations for new churches from Lakotas with no money simply to dismiss their faith as false. Hunts His Enemy, an esteemed warrior and holy man, took the name George Sword and became a deacon in the Episcopalian Church but never ceased to be wary of the old spirit powers. Many, perhaps even most, Lakotas retained at least some of the old beliefs, but to these they added Christian faith. Baptism and church attendance alone may not have been indicative of the kind of conversion idealized by missionaries, but the fact that so many Lakotas could be counted among the faithful provides evidence of the popularity of Christianity among them.56

The ubiquity of missionary teachings and Christian precepts on the Plains helps to explain a key aspect of the response to Wovoka’s teachings in the region: the widespread association of the Ghost Dance, not just with a messiah, but especially with Jesus. Jack Wilson prophesied a messiah, but he did not mention Christ or Jesus in his meeting with Arthur Chapman, the army scout who sought him out in 1890, or when he met (as we shall see) with James Mooney in 1892. A Paiute contemporary claimed that the prophet never referred to Jesus, not even in later years. It seems possible that Wovoka anticipated some other messiah than the Son of Man.57

But Plains believers mentioned Jesus or Christ frequently in their Ghost Dance teachings, perhaps because they gained more exposure to Christianity from missionaries, who were more numerous on the Plains than in Nevada. When word came from the west that a redeemer was on his way to save his Indian children, some Plains believers were quick—much quicker than Paiutes—to call him Christ. Lakota visionaries frequently met Christ in their Ghost Dance visions. According to a white observer among the Northern Cheyenne, they called the religion “the Dance to Christ,” and of course Christ appeared regularly in Porcupine’s account of his journey to Nevada. He and some others seem to have maintained that Wovoka himself was the savior. The Jesus of Ghost Dance visions differed substantially, however, from the Christ extolled by missionaries, and some Ghost Dancers claimed that their messiah was a different presence altogether. Nevertheless, references to Jesus were so pervasive on the Plains as to lead at least some observers to believe that the religion could be co-opted by authorities. In Oklahoma, Lieutenant Hugh Lenox Scott of the US Seventh Cavalry attended Ghost Dances and spoke often with leading evangelists. Many years later, he recalled the trances of Southern Arapahos who had “gone above in conference with Jesus,” and he lamented the failure of missionaries to seize the opportunity when “the name of Jesus was on every tongue.” “Had I been a missionary,” he maintained, “I could have led every Indian on the Plains into the Church.”58

IN OTHER CIRCUMSTANCES, HOLY MEN LIKE SHORT BULL OF THE Brule Lakota might have more easily accommodated themselves to the growth of Christianity. It would have been possible to integrate some Christian teachings into Lakota religion, or for the two religions to coexist in ways that would have allowed holy men to retain authority for the many Lakotas who continued to require their guidance. But intolerance of Indian religions by officials and missionaries made such accommodation difficult, if not impossible. Unless Indians found some way to resist, the pressure of assimilation, and especially the ban on the Sun Dance and other rituals, would be a death blow to their religion.

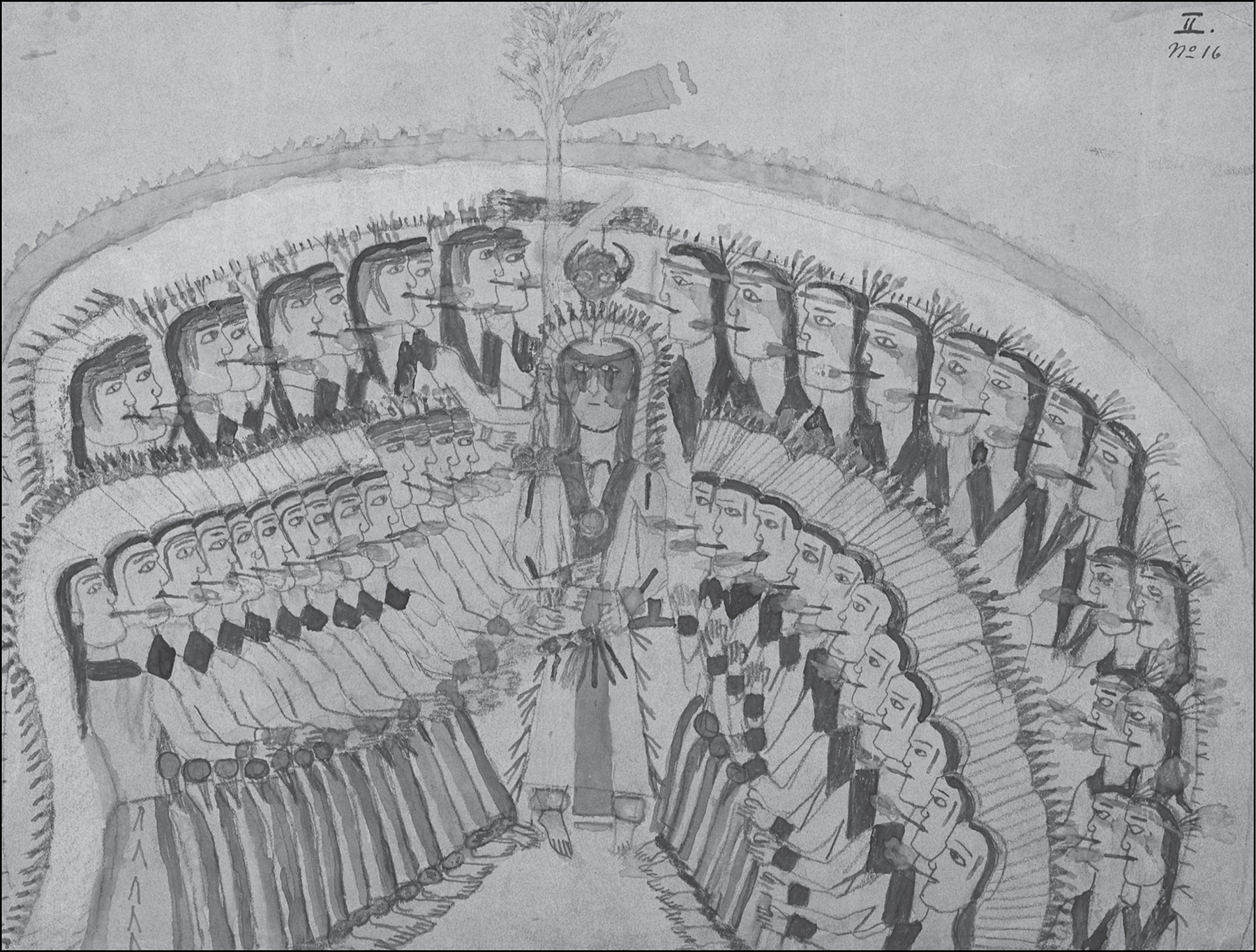

After Wounded Knee, Short Bull would spend several years touring Europe and the East with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. His colorful, evocative drawings of Lakota dances, enhanced by his notoriety as a leader of the Ghost Dance, made him a favorite of European collectors. Aficionados of Indian art and culture sought him out for years after. The German collector Frederick Weygold visited him at Rosebud in 1909 and either commissioned or was given a watercolor image of the Sun Dance. Rendered in vivid red and blue and accented with inky black, the vibrant painting suggests the energy and communal bonds of the ritual and the world that took shape around it. The image is dominated by forty-nine dancers in two ranks, all clutching eagle bone whistles with eagle plumes at the end that flutter like smoke as the whistles blow, invoking the voice of Eagle, himself one of the Wakan Tanka. The balance of the dancers gathered around the re-erected tree, ornamented with gifts to the Sun, suggests the power and meaning of the tree: when the tree went up, the world was made complete. A powerful degree of community is suggested by the close ranks of dancers, with their similarly painted faces and whistles, all oriented toward the center and united in ritual devotion. At the center, staring out at the viewer and holding the sacred pipe, is the holy man and intercessor in charge of the ritual, perhaps Short Bull himself. The image conveys a powerful sense of longing and sorrow, not only for the ritual, but for the world it once called into being.59

FIGURE 6.4. The Sun Dance, as painted by Short Bull, 1909. Museum Für Völkerkunde zu Leipzig.

So with many other people on the Plains. The Ghost Dance flowered in the empty space that remained when the Sun Dance receded.60 From this radically transformed landscape, desiccated by drought and poverty, Lakotas sent their emissaries west in search of the new religion. Short Bull’s quest was in many ways a continuation of the religious struggle that had overtaken the reservations as the bison vanished and poverty mounted. Wovoka’s prophecy promised a restoration of the ceremonial circle shattered by the ban on customary religion and a new balance between people and spiritual forces to ensure abundance, peace, and freedom. This hope drew Short Bull and other Brules and Oglalas westward to Nevada, along with Cheyennes, Arapahos, Shoshones, and others, in search of a way not only to save their own authority but to bridge the looming abyss that had opened in the spiritual and communal lives of America’s Plains Indians.