EPILOGUE

BEGINNINGS

IN JANUARY 1891, WITHIN TWO WEEKS OF SURRENDERING THEIR guns, Short Bull, Kicking Bear, and some two dozen other Ghost Dancers were arrested by the army and placed aboard a train to Chicago. On arrival, troops escorted them to Fort Sheridan, where they were held as “hostages” against future uprisings. The lodgings were not uncomfortable, and as Short Bull recounted later that year, the Indians were often “visited by General Miles who with all the officers made us as comfortable as could be, doing all in their power for us.”1

For all that, the Lakotas must have felt a sense of dread upon first seeing Fort Sheridan. The place comprised a 700-foot-long, two-and-a-half-story brick barracks, flanking a mock castle gatehouse, topped by a stone turret that, at 228 feet, was taller than any other building in greater Chicago. Designers patterned the turret after the bell tower in Saint Mark’s Square in Venice, but with enough mock arrow loops and buttresses to resemble a medieval battement. (It actually housed the fort’s water tower.)

Fort Sheridan was new—so new in fact that the imprisonment of Ghost Dancers was its first military duty. With its intentionally foreboding appearance, the architects had been commissioned to design it for enemies closer by. The looming tower guarded the shore of Lake Michigan not as an outpost of the Indian War to the west or to fend off foreign invaders from the east, but to suppress the nascent labor movement in Chicago.

In the aftermath of the Haymarket Bombing of 1886, many elites had anticipated a civil war between capital and labor. Marshall Field and other prominent businessmen of the Chicago Commercial Club had donated the land to the federal government with a petition for a fort; they wanted the army to be deployed quickly should fighting erupt between businessmen and the ranks of immigrants and unionists in the city. Construction began in 1887, and the final tiles were installed on the tower roof in 1891, the same year the Ghost Dancers arrived.

Three years later, in 1894, as Kiowas began to turn the Ghost Dance circle in Oklahoma and James Mooney was submitting the completed manuscript of his Ghost Dance book to his employer, the prophecy of class war came true to some extent. The army, once again under the command of General Nelson A. Miles, marched out from Fort Sheridan against strikers at the company town of Pullman, seized control of the rail yards, and ended a strike and shutdown that had paralyzed much of the nation’s rail network. The ensuing riots across the country killed thirty-four people.2

Even though Fort Sheridan had been built to crush civil insurrection, its use as a prison for Ghost Dancers was fitting. As we have seen, immigration and the emergence of new ethnic groups, worker unrest, and the persistence of Indian religions and communities were interlocking social and political challenges in the last decade of the nineteenth century. Despite the continuing presence of native-born white Americans in the ranks of labor, by 1890 the increasingly immigrant composition of the working classes seemed to signal a social crisis to many observers. The Ghost Dance had inspired panic in part because it came at a moment of profound cultural anxiety about assimilation, social order, and the alienation of the working masses from more well-to-do Americans. Fort Sheridan itself was a monument to the military solution many sought for dealing with immigrants and Indians alike.

The journey of the confined Ghost Dancers would take another turn through the workings of a popular entertainment devised both to soothe and, to a degree, exploit these profound anxieties. In the spring of 1891, William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, the onetime army scout and buffalo hunter who had achieved transatlantic celebrity as the impresario of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, arrived at Fort Sheridan. His show was preparing for another European tour, and he invited the prisoners to join them. When his energetic publicist, John M. Burke, followed up to press the matter, he made “such grand offers to see the ‘great country beyond the water’ with good salary that we all consented to go,” remembered Short Bull. Perhaps sealing the deal was Cody’s promise to reunite them with family members. The Ghost Dancers, isolated from their kin and far from home, were thrilled when Cody brought along sixty friends and relatives from Pine Ridge to accompany them overseas.

Crossing the Atlantic to Belgium, the Ghost Dancers and their families went to work in the modern entertainment industry. Short Bull made $25 per month (far better than the wages he earned as a freighter) to enact—or “re-enact,” as the show programs claimed—battlefield exploits at Little Big Horn and elsewhere. He and the others danced for paying crowds, sold handcrafts to collectors and souvenir hunters, and learned the ropes of modern show business and modern travel. After tours of Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands, the show moved on to Britain.

It was probably during the performances in Glasgow that autumn that Short Bull dictated his memoir to the show translator George Craeger. The holy man liked Buffalo Bill’s Wild West: “Ever since I have been with the Company I have been well treated and cared for, all of the promises made have been fulfilled.” Cody and the show managers “are our friends, and do all they can for us in every way.” There was food, clothing, work, and money, and “besides we go everywhere and see all the great works of the Country through which we travel.” Whatever complaints the Indians had were addressed at once, and “if we do not feel well, a doctor comes and looks after us.” If the holy man was bitter about events in South Dakota, he did not show it. He had only one complaint about Great Britain. “I like the English people but not their weather as it rains so much.”3

Short Bull’s career in the show led to other artistic endeavors. It was probably during this European tour that he first met the German artist Carl Henckel. In 1893 the two met again when Short Bull rejoined the Wild West show to work in Chicago outside the World’s Columbian Exposition. Henckel sketched a portrait of Short Bull, and the holy man sold him some of his ledger book drawings—including two of Annie Oakley. Short Bull and Cody reunited when Cody came to Pine Ridge in 1913 to reenact the Wounded Knee Massacre for his movie The Indian Wars. Short Bull assisted in the organizing and is said to have appeared in the film, although it is impossible to know for sure: the nitrate film degraded over time and no copy is known to exist.4

Cody titillated the press with tall tales of the Lakota survivors of the original massacre threatening to use real ammunition in the filming. This was pure publicity, with no basis in fact. The film departed from history in other ways as well. It contained no references to Wovoka’s teachings about work, farming, and education, and to avoid stirring the undying controversy over the massacre, the filmmaker whitewashed the atrocity, staging no bodies of women and children and perpetuating the fiction that the massacre was a “battle.”5

Back in South Dakota, in August 1891, the Wazhazha Brules had at last secured their transfer to Pine Ridge, and so Short Bull returned to Pass Creek when he left the Wild West show. In 1898 he and the other Wazhazhas moved away to join other onetime followers of Crazy Horse in founding the town of Wanblee, in the northeast corner of Pine Ridge Reservation, on Craven Creek. There in future years he spoke often about the Ghost Dance and earned money by selling paintings, drawings, and ethnographic information to visiting scholars and collectors.6

Although his memory of events seems to have shifted and become more mystical over time, Short Bull’s rendering of the teachings remained remarkably consistent. In 1906 he met with Natalie Curtis, a collector of Indian music. In a lyrical, mysterious account, he related to Curtis his geographic and spiritual journeys in the Ghost Dance, his passage through both the West and the spirit world, and the impact of these travels on his life.7

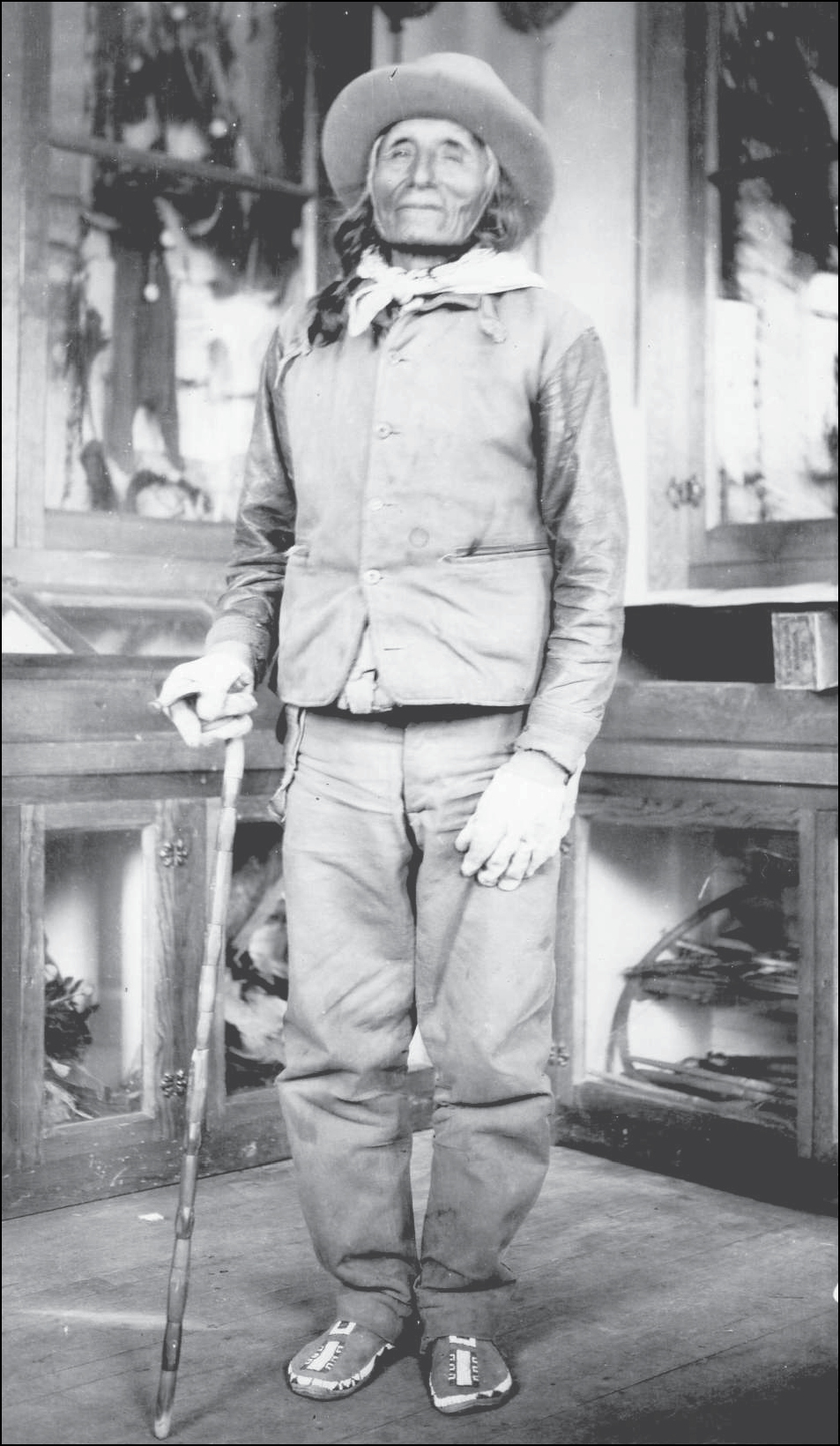

E.1. Short Bull at Saint Francis Mission, Rosebud Reservation, South Dakota, ca. 1892. Note the work gloves. Buechel Memorial Lakota Museum, Saint Francis, South Dakota.

He said nothing about the Ghost Dance code for good living. In 1909 he was sought out by the German artist Frederick Weygold, to whom he recounted his conversations with the prophet. In this interview, Short Bull almost seemed to depart from his earlier contention that the religion insisted on farming, schooling, and church. He quoted a seemingly nativist admonition from the prophet that believers should “abandon the way of the Whites” who “cursed us.” As Short Bull explained, “The Indians were made by the Great Mystery and only for living in a certain way and they should (therefore) not accept the ways of another people.” But it seems more likely that in relaying to Wegyold the teaching that believers should “abandon the ways of the Whites,” Short Bull (and, we may assume, Wovoka himself) meant that Indians should abandon the ways of unrespectable white men, of those who “cursed us.”8

This interpretation allows us to reconcile the command to set aside the ways of white people with the instructions that Short Bull said he delivered to followers before each Ghost Dance. As he told Weygold, all dancers were told, “Your children should go to school and learn. The old people should attend some religious worship and say prayers.” He instructed his followers to “draw something [from] the earth, too [that is, do some farming or gardening] and they should build houses to live in, and take good advice from respectable white men, too. Then do not kill each other!”9

In 1915, Short Bull dictated a narrative of his Ghost Dance experiences for Father Eugene Buechel, a Jesuit priest at Pine Ridge. He said that a trance overtook him in the dance circle and he saw “the Son of God,” who instructed him to teach the people, “under your clothes, always paint your bodies.” This cryptic but suggestive instruction may have been an exhortation to remain true to Indian ceremonies and traditions, even while assuming the clothes and trappings of white society. In other words, the Ghost Dance authorized Indians to become successful in the reservation era, even as it empowered them to resist the onslaught of assimilation.10

He remained mystified by the violence that consumed the religion. “Who would have thought that dancing could make such trouble?” he wondered to Buechel. “We had no thought of fighting; if we had meant to fight, would we not have carried arms? We went unarmed to the dance.”11

Known as a gentle, retiring man, Short Bull lived so long that the date of his death is something of a mystery. One account says that he died in 1915; another says 1923. Still another claims that he lived until 1935. Family lore maintains it was 1921. Whenever Short Bull left this earth, he carried with him throughout his life a profound religiosity, a strong work ethic, and a palpable sense of injustice over what had happened at Wounded Knee and in the whole sad travail of American conquest. “In this world the Great Father has given to the white man everything and to the Indian nothing, but it will not always be thus,” he prophesied to Natalie Curtis. “For ere long this world will be consumed in flame and pass away. Then, in the life after this, to the Indian shall all be given.”12

Viewing the Ghost Dance as a religion engaged with modernity, we should not be surprised at those turns in Short Bull’s biography that might otherwise seem strange—the passage of a Ghost Dance evangelist and holy man to earning wages on European tour with a Wild West show, working in the movies, and becoming a paid consultant to collectors and anthropologists. All of these pursuits were in keeping with the teachings of Wovoka, who encouraged his followers “to work all the time and not lie down in idleness,” either in jobs or on their own farms, and to be true to the cause of peace. To live by a religious code is a demanding task. Short Bull was human, and therefore not perfect. But to judge by the record he left us, he lived an exemplary Ghost Dance life.

AFTER LEAVING PINE RIDGE, WILLIAM SELWYN, THE YANKTON Dakota postmaster who fed inflammatory rumors about the Ghost Dance to officials, became renowned, and in many quarters reviled, for his land dealings at his home reservation in South Dakota, 200 miles east of Pine Ridge. When he called for the sale of the Pipestone Quarry—a sacred site entrusted to Yankton Dakotas for safekeeping by other tribes in decades past—he found powerful allies in Washington. He also earned the enmity of many Yanktons. Selwyn became adept at submitting language for congressional bills to Washington officials. Some that became law benefited him at the expense of other Yanktons and even allowed him to purchase particular parcels of land. Returning by train from a negotiation in Washington, one of his fellow Yanktons denounced Selwyn as a traitor to his people. Selwyn dropped him with a single punch to the head.

The identity of Selwyn’s antagonist is unknown; family lore identified him only as a maker of beautiful handwoven ropes. But others among Selwyn’s opponents were well known indeed. Leading their ranks was Selwyn’s own father, Chief Medicine Cow, who found himself campaigning against land cessions championed by his son.13

After 1900, Selwyn served as agency farmer at Yankton Reservation. He received cash payments on behalf of the tribe for rations and clothing, and he accumulated hundreds of acres of land.14

On August 22, 1905, Selwyn was repairing fences on his farm when a group of Dakota riders approached. According to family lore, he knew the men well. They came to deliver a traditional punishment ordered by the tribe. There was no appeal. He probably fought them, but they roped him around the middle and tied his hands behind his back. Then they galloped away, dragging Selwyn across the prairie, flaying him alive on thorn bushes, rocky outcrops, and finally against a long length of barbed-wire fence. His skin was practically gone when his family found his lifeless body—wrapped in a beautiful handwoven rope.

“We never pressed the issue,” recalled his son many years later, “because Dad was in deep. He knew what he was into.” His land dealings were at the root of his killing, but his part in Wounded Knee was not forgotten either. In 2009 another descendant concluded, “The Ghost Dance tragedy might not have happened at all had he kept his opinions to himself.”15

JOSEPH HORNED CLOUD LOST MANY FAMILY MEMBERS AT Wounded Knee. With those who survived, he settled at Pine Ridge. There was not much choice: the government confiscated much of the Cheyenne River Reservation, including the land on which the Horned Clouds had built cabins and grazed their stock. Thereafter, his life was punctuated by persistence and a good deal of protest, as if he carried with him an understandable need to recall the Seventh Cavalry’s brutal betrayal. Horned Cloud led the campaign for a monument to the victims of the massacre, and in 1903 he saw its dedication at the hilltop mass grave, where it yet stands. Ten years later, in 1913, he translated for Buffalo Bill Cody when the showman came to Pine Ridge to film his reenactment of Wounded Knee. Disenchanted with Cody’s misleading presentation of the massacre as a battle, he would protest the film’s many inaccuracies.16

In his life’s work, Horned Cloud transcended old grievances and embraced questions of faith and justice. A man of religious devotion, he became a catechist for the Catholic Church, on whose behalf he traveled across the country. In 1920 he appeared before a US House of Representatives committee and denounced, in scathing terms, the graft and corruption associated with the leasing of Indian land at Pine Ridge. He died later that year.17

AFTER PUBLISHING HIS MONUMENTAL GHOST DANCE STUDY in 1896, James Mooney spent more than two decades in research mostly on the Southern Plains, primarily among Kiowas, compiling studies of Kiowa heraldry and language, publishing more work on Cherokee myth, and organizing exhibitions of Indian artifacts and history at world’s fairs and expositions. By far his most captivating research was on the Peyote Religion, through which he began to imagine a very different kind of Indian history than had ever before been told.

Mooney’s writing about Indians, at least in the first half of his career, had been characterized by the romantic impulses of the salvage ethnologist: an overarching sense of decline in Indian societies, an assumption that all genuinely “Indian” ways were passing as Indians were gradually assimilated into white society, and an urgency to collect “authentic” Indian customs, languages, and artifacts before they irretrievably disappeared.18

The Ghost Dance had opened his eyes to the possibility of a new Indian religion, as authentic as the old, and his subsequent work on the Peyote Religion took him even further in this direction. Perhaps it was the Irish rejection of assimilation that allowed Mooney to imagine Indians doing the same. In any case, the longer he spent studying Peyotism, the less certain he was that Indians were destined to vanish. Like dance, peyote ritual fascinated him in part because it represented a means of strengthening and propagating Indian community and ceremony. It allowed Indians to adapt to modern reservation life and yet remain distinctive from whites. It allowed them, in other words, to be unassimilated and forthrightly Indian, even as it helped some believers prosper in modern occupations.19

Two articles he published on the subject suggested that his book about the Peyote Religion would rival his work on the Ghost Dance. But after this burst of energy and some promising results, he put the Peyote Religion on the shelf—or perhaps he merely kept his research secret. For many years, it ceased to appear in the progress reports he filed with the bureau. He never said why, but the reasons seem clear. Mooney had already alienated Indian agents with his defense of the Ghost Dance and other ceremonies. In 1903 he barely managed to fend off potentially career-ending charges that he had paid a Cheyenne pledger to pierce himself at a Sun Dance near Darlington. (The man had been pierced, but Mooney had not intervened in the ceremony.)20

Peyote proved at least as controversial as the Ghost Dance and the Sun Dance. Despite the fact that the Peyote Religion lacked either a millenarian prophecy or a central dance ritual—two features of the Ghost Dance that caused much official anxiety—government agents came to abhor it at least as much as other forms of Indian worship. Many confused it with the more dangerous mescal bean and considered peyote a narcotic (which it was not). When officials demanded, as early as 1886, that it be banned, the popularity of the Peyote Religion among Indians only expanded. In 1899, culminating over a decade of Indian agency efforts to disrupt peyote meetings, the state of Oklahoma outlawed peyote.21

In this climate, Mooney’s endorsement of peyote as a positive good earned him the enmity of missionaries and officials. “Mooney encourages Indians in heathenish dances and mescal dissipation,” wrote J. J. Methvin, the Southern Methodist missionary at Anadarko. According to Methvin’s sources, Mooney had been telling Indians that peyote was good for them and that their children should be educated at reservation schools instead of at Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. Methvin passed these rumors along to Richard Henry Pratt, founder and head of the Carlisle school and still a force in the making of Indian policy. Pratt, in turn, warned Secretary of the Interior Hoke Smith that Mooney “is not a fit person to be allowed among the Indians for any purpose.” Smith warned Powell to rein in Mooney.22

What Powell told Mooney is unknown. Apparently, the ethnologist continued to work with peyote believers on a variety of other projects, but his official reports ceased to mention peyote.

The boom finally came down in the closing days of World War I. Mooney was deeply opposed to the war. Like many Irish and American patriots, he saw the conflict as a struggle between imperial powers for world domination, and one whose effects were prejudicial to social tolerance and intellectual inquiry. In the United States, the war advanced a wave of anti-immigrant sentiment and support for the temperance cause. Late in 1917, both houses of Congress passed the Twentieth Amendment to the Constitution to ban the production, transport, and sale of alcohol, and they made similar efforts to regulate and ban other drugs, including opium, marijuana—and peyote. It was at this moment that Mooney’s long interest in peyote led him into a political ambush.

In February 1918, Congress convened hearings on a proposed federal law to ban peyote. Mooney, called as a primary witness, spoke eloquently in defense of the Peyote Religion. As he explained to the congressmen, younger, educated Indians found the religion helpful in restoring health and well-being, and they were the ones—not embittered old-timers—who built churches and led the movement. Peyote was used ceremonially and, he said, medicinally, but never recreationally. He had consumed peyote as part of his research “eight or ten times,” up to seven or eight buttons at once, and he had brought fifty pounds of peyote to Washington for chemical analysis. In all his time among Peyotists, he said, he had seen nothing that could be described as immorality. In fact, the religion forbade the drinking of whiskey and encouraged hard work. In his view, peyote was the sacrament of a religion that was “not a Christian religion, but a very close approximation” that might itself lead Indians to Christianity.23

“I favor the continuance of this peyote religion among the Indians as a religious ceremony,” concluded Mooney.

“Why?” asked a hostile congressman.

“Because it is their religion,” replied Mooney, adopting the language of the First Amendment. He also favored the religion, he said, “because they understand it, because it kills out whisky drinking among them, and because we have medical testimony that, as they use it, it is practically impossible to take an overdose, and because it does not result in a habit.”24

Mooney’s testimony was politely received, until he later returned to rebut the claims of several anti-peyote witnesses. As he finished, he was interrupted by another luminary in the room: Richard Henry Pratt. The founder of Carlisle Indian Industrial School had long since made it his mission to destroy Mooney’s reputation, and he had been lying in wait. “I feel I would like to say something about the gentleman who has just spoken,” Pratt blurted out. He then smeared Mooney with the allegation from fifteen years before that Mooney had paid a Cheyenne Indian to pierce himself in the Sun Dance at Darlington in 1903.

Mooney was furious. “General Pratt is old enough and has been in an official position long enough to know that he must investigate his statements before he declares them.” His charges were “an absolute falsehood” that had been “denied on investigation by every man who asserted it and he knows that.” Mooney offered to furnish documents to prove his case.

Pratt bragged that he, too, could present evidence. “You ethnologists egg on, frequent, illustrate, and exaggerate at the public expense, and so give the Indian race and their civilization a black eye in the public esteem.” He suggested that Mooney himself had fomented the Ghost Dance—“white men were its promoters if not its originators.” Now “this peyote craze” was “under the same impulse.”

“You can not furnish proof, because there is no proof,” snarled Mooney.

The chairman waved off the two antagonists and called the next witness.25

If the dispute seemed irrelevant to the chairman, it showcased a central disagreement between assimilationists like Pratt and the ethnologist-cum-activist James Mooney. To Pratt, Indianness had to vanish for Indians to become economic actors and citizens. Mooney had once thought the same. But by 1918 he had come to believe that while Indians would have to become workers, Indianness was flexible and adaptive, and also that Indian religion and ceremony were assets to those seeking to reconcile themselves to reservation lives through work and farming.

That fall, when Mooney returned to Oklahoma, he saw firsthand the deep appreciation of his efforts as separate delegations of Comanches, Wichitas, and Caddos traveled as far as sixty miles to see him. “My reception by my old Kiowa friends and other Indians was almost an ovation,” he wrote.26

The congressional hearings and the impending ban on peyote had energized these peyote believers. Throughout the state, Indians were organizing to defend their religion. A group of Oto, Kiowa, and Arapaho believers, including Mooney’s translator and consultant Cleaver Warden and the Ghost Dance leader Paul Boynton, convened in the town of Cheyenne, Oklahoma, to discuss the defense of peyote. Mooney joined them. Four years earlier, the peyote leader Jonathan Koshiway had led the incorporation under state law of the first peyote church—the First-Born Church of Christ—at Red Rock, Oklahoma. Now, in the summer of 1918, Koshiway attended the gathering at Cheyenne with charter in hand. According to lore within the movement, James Mooney helped persuade those present that incorporation under the law, like the First-Born Church of Christ, would provide legal protections for peyote believers. Mooney also, it is said, originated the name for the new organization. On October 10, the charter of the Native American Church was registered with the state of Oklahoma.27

Mooney, Warden, Boynton, and others had all learned lessons from defending the Ghost Dance that they now applied to the Peyote Religion. In their struggles to defend the teachings of Wovoka, believers had articulated them as “their religion,” and Ghost Dancers had even spoken of it as their “church.” Now Peyote believers, with many Ghost Dancers among them, were organized into a legally defined church, an institution with protected status under the US Constitution.

But opposition mounted. Even before the charter went to the state, missionaries and anti-peyote activists had been put on notice by that winter’s congressional hearing, and they had Mooney in their sights. In August a visiting missionary complained that one “Mr. Mooney of the Smithsonian Institute” was encouraging “old tribal customs” and the use of peyote. Church-based Indian uplift organizations began denouncing Mooney in their newsletters for “encouraging a demoralizing practice among the Indians.”28

In Oklahoma, Indian agents eagerly joined the anti-Mooney campaign, led by the superintendent of the Kiowa, Comanche, and Wichita reservation, C. V. Stinchecum—the same man who was at that moment persecuting Kiowa Ghost Dancers. Stinchecum assailed Mooney’s support for peyote and sent a telegram to his superiors demanding the anthropologist’s “immediate recall” to Washington. Commissioner of Indian Affairs Cato Sells obliged, banning Mooney from all Indian reservations. On October 23, 1918, Mooney was ordered to leave the Kiowa reservation and return at once to Washington.29

He never returned to Oklahoma, or to any Indian reservation. Mooney’s dissenting views, especially about the Peyote Religion and the role of scientists in a democratic republic, would now cost him a great deal, partly because he had few defenders in the profession. Powell had long since died. Anthropology was becoming more professional, requiring graduate training, and Mooney did not even have a college degree. Unable to hold an academic position, he never trained students, and no cadre of defenders emerged on his behalf. As a government employee in a nation gripped by assimilationist hysteria and denunciations of “foreign” influences and “un-American” thinking, Mooney, in his devotion to religious dissent and Indian autonomy, earned only unbending censure. Now effectively barred from Indian reservations, Mooney appealed twice to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs for permission to return to his research in Oklahoma. He met personally with Secretary of the Interior John Barton Payne. Early in 1921, Warren G. Harding succeeded Woodrow Wilson as president. Mooney appealed to the new commissioner of Indian affairs, Charles H. Burke. But all to no avail. Each appeal was blocked by his superiors at the Smithsonian Institution.30

Behind Mooney’s persistence was an ironclad belief in the utility and morality of science, including social science, as a method for locating and identifying the truth. In one of his final appeals, he stated that his disbarment had “left me in the position of a condemned criminal for a period of three years, to the demoralization of my best work, the undermining of my health and the injury of my reputation built up by years of honorable service in the bureau.” Not only was his heart condition “aggravated almost to suffocation point with any long confinement at the desk in the damper atmosphere of Washington,” not only had no ethnologist “ever before been held to the desk for as long a period or under such conditions,” but despite being “pledged before the scientific world” to investigate the Peyote Religion, the bureau was refusing to do its duty.31

In Mooney’s view, that pledge—to explore the Peyote Religion using the tools of science—required the pursuit of the truth, whatever it turned out to be. To turn away from peyote because it challenged conventional belief and assimilation policy would have been profoundly unscientific and immoral. To Mooney, if there was anything that modern society—“civilization”—offered to the world, it was the practice of good science. His disbarment hurt as a professional slight, but it also represented the triumph of politics over scientific inquiry. In the pursuit of truth that defined the purpose of civilization, the United States had failed.

Mooney’s defense of science was stalwart, but perhaps his greatest achievement was to have realized the essential humanity of Indians, grasped their authentic, ongoing contributions to religious experience in modern America, and aided in their protection. Mooney had become an intellectual partner to Indians in developing new tools for defending their religions from assimilationists. In this two-way process, Mooney had learned from Indians the value and meaning of Indian belief. What John Wesley Powell and others called “superstitions” and “primitive” beliefs came to represent to Mooney realms of spiritual practice that should be sheltered under the First Amendment.

He made his claims based on the US Constitution and traditions of religious tolerance—which he helped to expand—but Mooney’s religious sensibilities derived also from growing up Irish-American Catholic and Irish nationalist. He never articulated as theoretical positions the fundamentally anti-imperial and anti-colonial thinking about Indians that these origins helped him develop, but his form of relativistic thinking about religions came to predominate in the intellectual circles of Franz Boas, a Mooney contemporary and himself a German Jewish immigrant. Boas and his students would be a generation of “outsider” anthropologists with versions of double-consciousness even more pronounced than Mooney’s. Many of Boas’s students were immigrants or children of immigrants from eastern Europe, and many of them were Jewish. Among their contributions was the abandonment of racial theories of development and social evolution for what came to be called “cultural relativism,” an approach in which all cultures have meaning and coherence in and of themselves and all are of equal value. Such ideas have become critical to modern American thought; what were once ominous ethnic and racial differences have now been transformed into assets of cultural diversity, which we know as a modern virtue. Mooney’s work linked the old developmental models for religious thinking so favored by the generation of John Wesley Powell with the new sensibilities nurtured by Boas and his students.32

The Catholic who posed as an Irish healer in order to secure the medicine books of Eastern Cherokees and who became a Ghost Dancer among the Southern Arapahos, had come to identify profoundly with American Indian believers in peyote and other ceremonies and religions. When he threw down a gauntlet to the reigning doctrines of cultural evolution and assimilationism, however, he brought down upon himself the full fury of American disapproval.

Still battling to return to Oklahoma, ailing and confined to a rocking chair on the third floor of his home in Washington, James Mooney died on December 22, 1921, at the age of sixty.33

Upon hearing the news, the Native American Church of Clinton, Oklahoma, adopted a resolution hailing Mooney’s “great work and the numerous acts of kindness rendered by this great man, to the Indians in general, and especially to our tribes.” In the church’s view, Mooney’s life had been “spent with a view of bettering our conditions through the Native American Church… making us able to become better citizens and to defend our religion as he knew it.”34

James Mooney’s contributions to the Native American Church had begun in the Ghost Dance. Jack Wilson’s prophecy fired Mooney’s ethnological imagination. It carried him along a course on which he would embrace divergent religious traditions and even become their spokesman. The Ghost Dance inspired his greatest work, but by entering the door it opened for him, he became a pariah in Washington, where he needed elusive public approval to continue his work. The Ghost Dance made and then unmade James Mooney’s career.

For all the defeat he encountered, Mooney never quailed or retreated from his convictions. The Ghost Dance and Jack Wilson’s vision led him toward acknowledgment of Indian religions, defense of intellectual freedom, and a view of the world as a place of many religions—as a bigger, and dare we say it, newer world.

ABOUT 1894, JACK WILSON’S EIGHT-YEAR-OLD SON, TIMOTHY, was killed when he was run over by a wagon. Grief consumed the weather maker. The skies opened, and rivers of rain descended. Then the clouds parted, and the storm ceased.35

Exactly when the Ghost Dance stopped in Mason Valley is hard to say. In the fall of 1892, the Indian agent in Nevada suggested that enthusiasm for the Ghost Dance had begun to wane: “I am happy to report this craze as almost having subsided at its cradle.” Part of the reason for its decline appears to have been growing reticence. That same fall of 1892, the Arapaho Sitting Bull led another delegation of Arapaho and Cheyenne to the prophet and were told by him to stop doing the dance. In October 1893, Black Coyote and others dictated a letter through James Mooney to the prophet, asking for red paint and other tokens of the prophet and inquiring if indeed he wanted them to cease their devotions; the answer, if it came, has been lost to the record.36

Wovoka may have been retreating from his earlier teachings, or he may have been merely lowering their public profile. As we have seen, he was still receiving Lakota believers more than a decade later. In Nevada, dances may have gone on secretly. After Mooney’s visit in January 1892, Wovoka refused to speak to any other official or anthropologist. Perhaps he felt that his goals had been accomplished. Perhaps he no longer saw the point of talking to white people about his religion. Local tradition does not say when the dances stopped, only that they did.

Sometime after 1910, Jack Wilson’s father died. Numu Taivo had been a powerful doctor, and now his prowess passed to Wovoka, who also became a potent healer. On the back of his Ghost Dance prophecies, his skills as a doctor became widely renowned. Indians in Oklahoma and elsewhere wrote him hundreds of letters. Wilson (who was illiterate) answered this correspondence with the help of his friend Ed Dyer, the Nevada storekeeper who spoke fluent Paiute and had served as interpreter for Wovoka and James Mooney in 1892. Many letters from Plains Indians came to Wovoka with the help of another Ghost Dance acolyte. As Ed Dyer recalled, they were “almost invariably post-marked ‘Darlington, Oklahoma’ and written by one Grant Left-Hand, who appeared to function as a scribe for most of the Indian Nation.”37

Many supplicants wrote to request red ochre paint or magpie feathers. In keeping with their traditions, petitioners readily sent a “gift”—a fee in exchange for the promise of health—and Wilson made a small living from this mail-order medical practice. Among other requests, correspondents often asked for some article of Wilson’s clothing, even for the large sombrero he typically wore. As Dyer recalled, “I was very often called upon to send them his hat which he would remove forthwith from his head on hearing the nature of a request in a letter.” Wilson charged $20 for his hat and bought replacements from Dyer. “Although I did a steady and somewhat profitable business in hats, I envied him his mark-up which exceeded mine to a larcenous degree,” wrote the storekeeper. “But somehow this very human trait made him all the more likable.”38

Wovoka’s fame extended far and wide. On at least two occasions, in 1906 and again in 1916, he traveled to Oklahoma, where he received money and gifts—mocassins, vests, belts, gloves, buckskin breeches, and “other articles of finery”—that “would have made a collector of Indian hand work green with envy,” recalled Dyer. Among the Numu, too, he held a place of great esteem. His renown extended even to white doctors. In the 1920s, Dr. George Magee, the contract physician at the Walker River Reservation, often consulted with Wovoka about medical cases. Magee later recalled that Wilson “took care of the bulk of the Indians,” even as he sent appendicitis cases, serious fractures, or other “severe things” to Magee. Paiutes spoke of Wovoka’s magic; Magee was in awe of his “amazing” technical prowess, which enabled him to perform eyelid surgery with a piece of salt grass.39

Meanwhile, Americans were doing their best to remove the need for the weather maker’s magic. In 1905 the massive Truckee-Carson irrigation project, the first project of the newly founded US Bureau of Reclamation, diverted the voluminous Truckee River into the Carson River just north of Walker River Reservation to fulfill dreams of irrigating 350,000 acres. Only after the first water was delivered, however, did officials test the soil, whereupon they discovered that the plains of the Carson Sink rested on a very high water table. Adding millions of gallons to the surface raised the water level so much that the roots of crops were submerged and killed. The project was plagued by decades of lawsuits from disappointed settlers, and water from the project ultimately reached only 60,000 acres. In the end, the bureau created a small fraction of the farms it had once envisioned. When it came to renewing the earth, the superiorty of the first bureau project over the Ghost Dance was not at all clear.40

In contrast, Paiutes could point to Wovoka’s success, however limited it might be. The prophecy of a world without work was not fulfilled, but work itself improved for a time. The blizzards of 1889–1890 wiped out enough Nevada cattle to crush the open-range cattle industry. Ranchers who survived the calamity invested more money in irrigation to raise hay for winter cattle feed, which became one of the largest sectors of Paiute employment. Perhaps the earth was not renewed, but by the early 1900s Paiute wages had reached record highs as Walker River employers bid against one another for their labor.41

Nevertheless, the 1890s were years of continuing struggle for Northern Paiutes. As the Ghost Dance receded from public view, opium addiction bedeviled the community. Jack Wilson condemned both opium and alcohol consumption for the rest of his life.42

As the opium struggle made so clear, Wovoka’s prophecy and his religion could not save Indians from the perils of the twentieth century. In Yerington, Numus eventually found permanent homes at a “colony”—lands purchased for them by Congress in 1916—and later, in 1936, at Campbell Ranch, an 1,100-acre tract held in trust for Yerington Paiutes on which they could farm. But in Yerington and beyond, each generation of Indians since the prophet’s day has struggled against the combined threats of continuing land loss, assimilation campaigns, and racial prejudice. After Southern Arapahos accepted allotments and agreed to sell the remainder of their reservation to the government, Southern Cheyenne opposition was overcome by intimidation and fraud. Over 50 million acres passed into US hands, and the Southern Cheyenne–Southern Arapaho reservation ceased to exist. None of these sacrifices prevented the poverty that followed. In South Dakota, Indian people did no better. To this day, Pine Ridge, Rosebud, and other Lakota reservations consistently rank among the poorest communities in the United States.43

For all that, Paiutes, Arapahos, Cheyennes, and Lakotas have never ceased working for a better day. Lakotas have pursued a vigorous revival of the Sun Dance; Southern Arapahos restored their Sun Dance, the Offerings Lodge, in 2006. And among all these peoples flourish continuing efforts to restore languages, ceremonies, and traditions and to secure education, work, and health. The quest for a life both traditional and modern goes on.

In his time, confronting the ongoing calamities of conquest, Jack Wilson never stopped trying to heal the wounds of others. As late as the 1920s, he doctored one Numu survivor of a car crash, who later remembered that he awoke to find Jack Wilson standing over him with an eagle feather, having miraculously removed every piece of shattered windshield glass from his body. Throughout his life, Wovoka also remained an ardent advocate of hard work and education, positions that earned him some credit with Indian agents and other officials.44

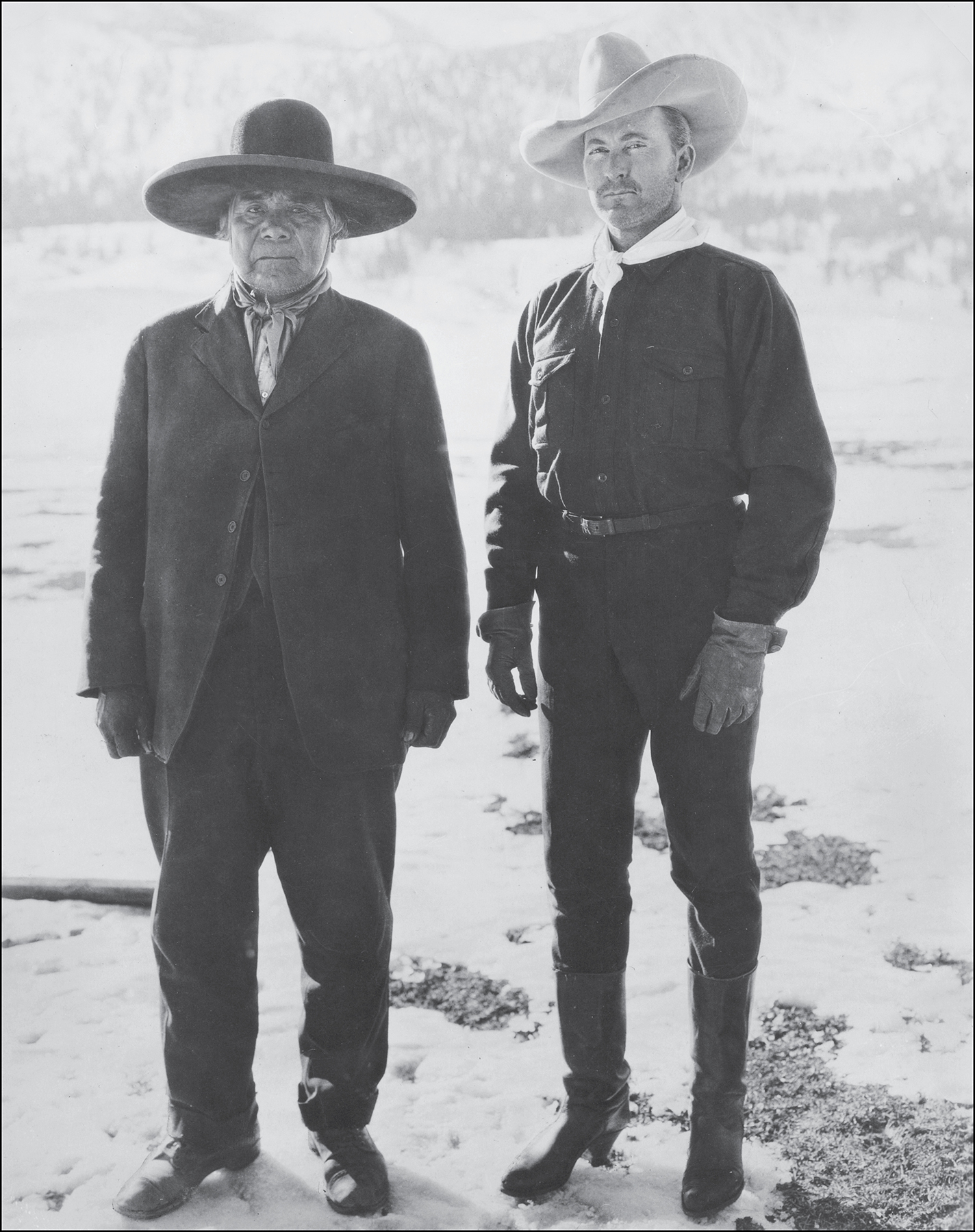

His fame endured among far-flung Indians. In 1924, Tim McCoy, Hollywood actor and director, filmed The Thundering Herd near Bishop, California. At the request of Northern Arapaho cast members, McCoy drove across the state line and returned with Wilson, who spoke to the cast about brotherhood, peace, and clean living before leading them in a dance and enjoying a feast in his honor.45

Late in life, the ailing healer told his followers not to worry, that when he died he would “shake the earth” to let them know he had reached heaven. He passed away in September 1932. Three months to the day after he died, a powerful earthquake rattled northern Nevada. Even his white acquaintances were awed. “Son of a gun, Jack!” remarked one. “Said he was gonna shake this world if he made it, and by God, he did!”46

ALTHOUGH HE COULD NOT KNOW IT, JACK WILSON’S FIGHT against the deadening hand of assimilation was practically won. Shortly before his posthumous earthquake in Nevada, political upheaval roiled the nation when Franklin Roosevelt won the 1932 presidential election, ushering in the New Deal, which would stem the assimilation policies of his predecessors for at least a generation. For the next twenty years, the government would encourage Indians to govern their own reservations and preserve their cultures. The tolerance that James Mooney had cultivated and that Jack Wilson and his followers had urged on the public was now official policy—at least for a time.47

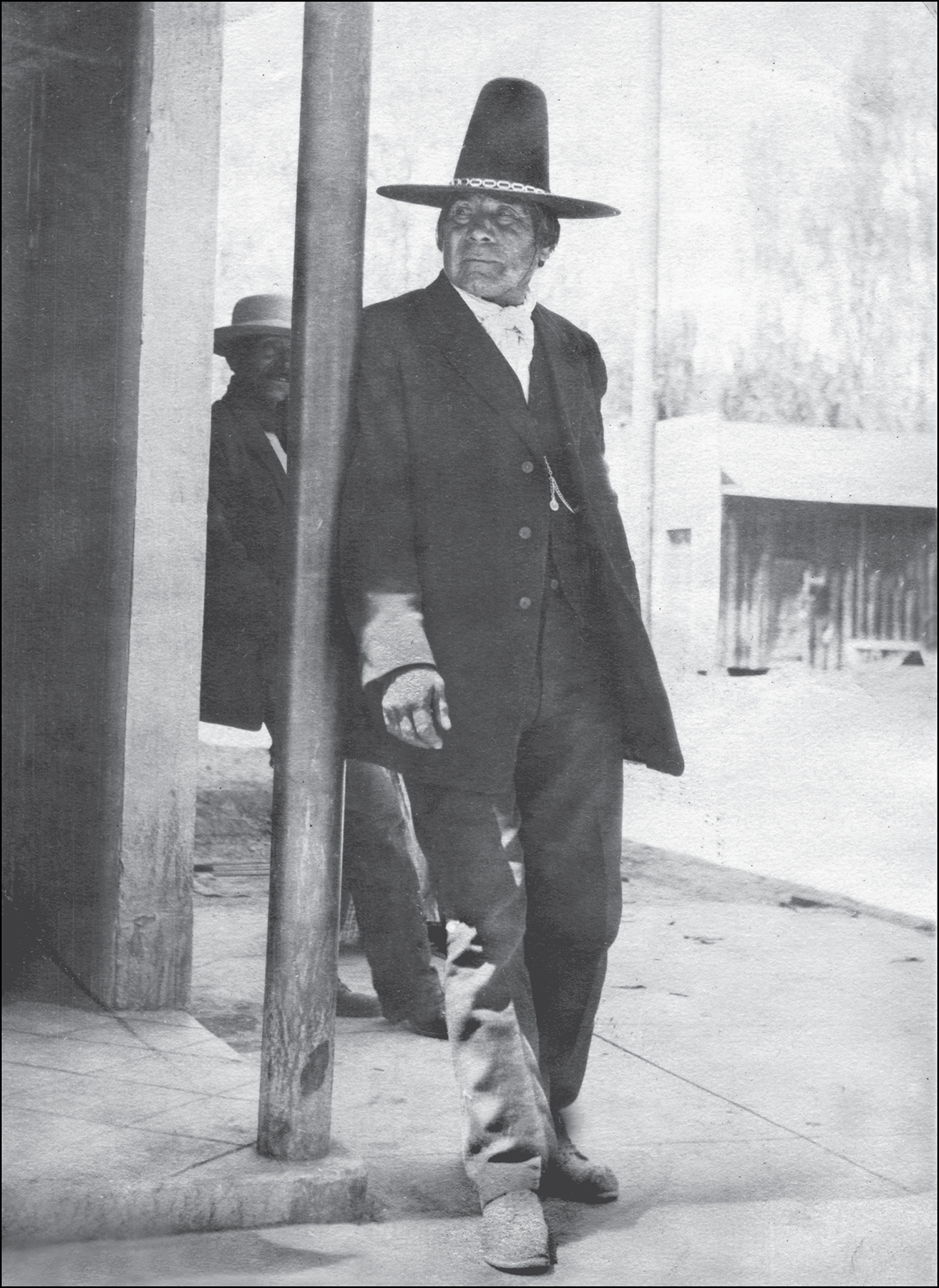

FIGURE E.2. Jack Wilson in Yerington, Nevada, ca. 1915. Nevada Historical Society.

FIGURE E.3. Wovoka and the Hollywood actor and director Tim McCoy, 1924. Nevada Historical Society.

Wilson and Mooney were not friends and did not know each other well. After their meeting at Walker River, their paths diverged, and they never met again and never corresponded. Wilson’s revelation started both men down paths, however, that would not only lead to their meeting but change their lives and in the end change American society too. Following them on their journeys, we have seen that their personal concerns often reflected the broader experience of region and nation. In the end, both men envisioned a multicultural America very different from their contemporaries’ ideal of a monolithic, English-speaking, Protestant country. In a sense, modern Americans who espouse pluralism as a social virtue carry on their teachings.

Although the Ghost Dance has been the coda for many stories of the frontier and Indian autonomy, we learn more by viewing it as a point of beginning. In following the entangled stories of Jack Wilson and James Mooney, Short Bull and Porcupine, Grant Left Hand and Moki, we have connected the Ghost Dance to the local crises that fomented it and the regional and national concerns that turned it into a much wider public emergency. We have also come to understand its surprising role in pushing scholars and the American public toward greater Indian autonomy and a broader acceptance of divergent religions and cultures.

The Ghost Dance events open a window on the United States at the dawn of the new century. The era saw not only a wholesale transformation in Indian policy but also an epochal shift in American understandings of the nation’s future. The Ghost Dance story points to a nascent current of thought that would often be marginal but never extinguished in the century to follow: the idea that difference truly is America’s great strength. Jack Wilson saw the meeting of cultures within our borders as a good thing. For James Mooney, the nation was an experimental borderland, and the lesson of the Ghost Dance was to not fear examining the results and learning the lessons of our many cross-cultural meetings. It was a teaching that would resonate through the entire century that followed.