15

APPLICATIONS OF SCIENCE

Wednesday, 28 August 1940.

In Moscow, there was still no word from Nikolai Vavilov, now missing for three weeks, nor any hint about his fate. In New York, Colin MacLeod was coming to terms with failure; he had flogged himself as hard as he could, but was not going to crack the identity of the transforming principle during his last few days at the Rockefeller. And in Liverpool, certain products of British research were about to sail for America in a black metal deed box, under circumstances that could have been lifted from a spy thriller.

The box was the size of a small suitcase, with an unusually sturdy lock and holes drilled in its sides. It belonged to Sir Henry Tizard, physicist and leader of the top-secret British Scientific and Technical Mission to America. Inside were blueprints for a revolutionary ‘jet’ aircraft engine, clever fuses for bombs, a device to detect distant aircraft and submarines – and a brief memorandum that predicted a bomb with unimaginable destructive power.

Tizard was already in Washington, preparing the ground for a difficult meeting. America was still neutral, with powerful voices arguing against getting involved in the war in Europe. Tizard’s role was to persuade the US military that Britain would be an effective partner should America be sucked into the conflict.

The box joined him two weeks later, having crossed the Atlantic with an armed escort ordered to sink it rather than let it fall into enemy hands.* When Tizard lifted its lid on 12 September 1940, the Americans were immediately bowled over by one of the treasures inside. This was a bulky tube several inches long, so astonishingly brilliant that the American scientists who took it away wished that they had thought of it first (and some later claimed that they had). The genius of the device lay in a squat copper cylinder with an array of circular holes drilled in one end, rather like the cylinder of a revolver. This was the ‘cavity resonator magnetron’, invented six months earlier by John T. Randall and Harry Boot of the Physics Department at Birmingham University.

Harry Boot has only a brief, walk-on role in the story of DNA, but John Randall’s part is pivotal. Without him, the tangled saga of the double helix would have had a completely different ending.

Power and glory

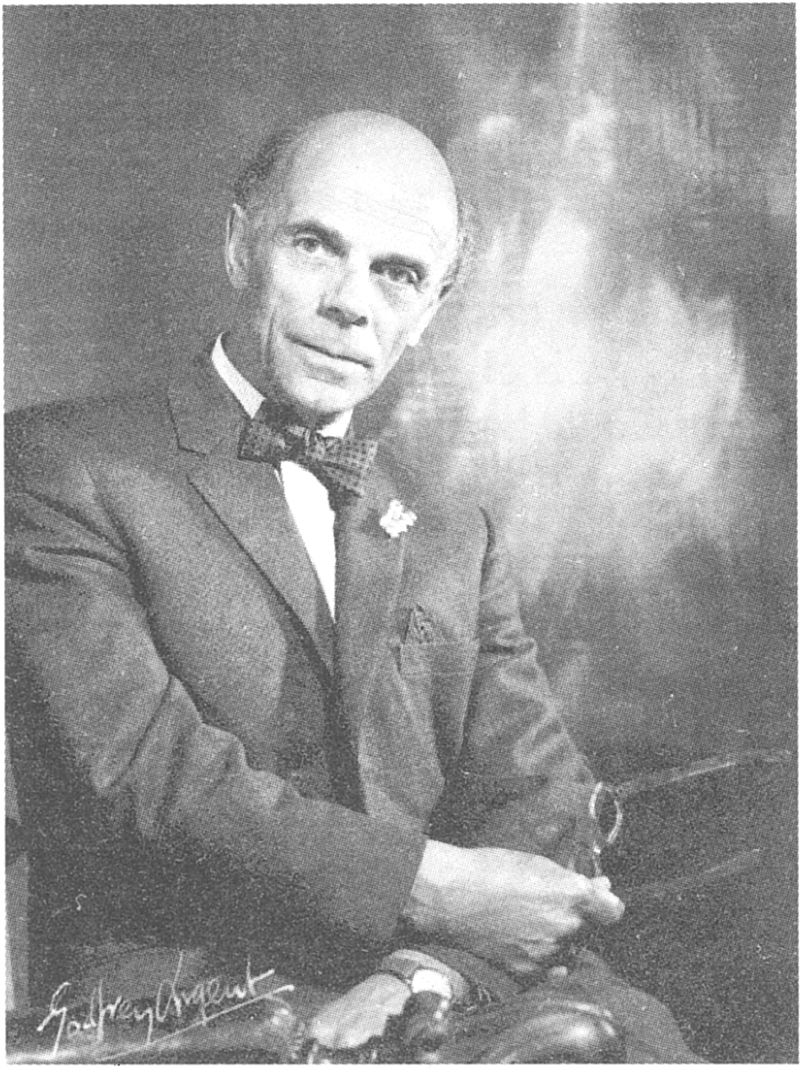

John Randall (Figure 15.1) was born in 1905, halfway between Liverpool and Manchester. He was seven years younger than Bill Astbury, with whom he shared his working-class origins, grammar-school education, and a career shaped by the Bragg dynasty. Randall studied physics at Manchester and graduated in 1922 with the best First of the year. He turned down the chance to do a Master’s with Lawrence Bragg because the Nobel laureate overawed him. Instead, he tackled a mundane aspect of X-ray crystallography that gave him no opportunity to shine. He failed to impress and later wrote, ‘They did not think well enough of me to keep me on.’ More bluntly, Bragg told Randall that his future lay in industry, not academia – a put-down which permanently clouded their relationship.

In 1926, aged twenty-one, Randall signed up with the General Electric Company in Wembley. His marriage to Doris Duckworth a couple of years later helped him to adapt to the ‘smooth South’ and to working in an ‘unusually talented group’ where rudeness and belligerence flowed as freely as clever ideas. He became an expert in ‘phosphors’ – luminescent powders that boost the light emitted by fluorescent tubes – and wrote a 300-page book about ‘X-ray and electron diffraction of amorphous solids’, which included rubber and wool.

Figure 15.1 John Randall.

All this enabled him to be rehabilitated into academia. J.D. Bernal wanted him in Cambridge, but could only pay half the going rate. In 1937, Randall won a Royal Society Fellowship and took it to the Physics Department at Birmingham under Mark Oliphant, an Australian nuclear physicist who had trained with Rutherford. Randall’s lab was a room with a sloping ceiling because it was tucked in under a raked lecture theatre; delicate instruments had to be recalibrated whenever the students overhead became restive and stamped their feet.

In 1938, Randall acquired a research assistant who wanted to do a PhD on luminescence. The applicant had rung Oliphant, who had supervised him as an undergraduate in Cambridge, to ask if there were any jobs going. Oliphant believed that he had potential, even though there was no hard evidence; the applicant had left Cambridge with a 2:2 in Physics. The newcomer was a tall, bespectacled, rather earnest twenty-five-year-old man called Maurice Wilkins (Figure 15.2). Oliphant told him that Randall was doing ‘interesting things’ with luminescence, and made the introductions. Randall was persuaded, and Wilkins signed up for a PhD in the Luminescence Lab.

They found each other engaging and stimulating company, but the PhD got off to a slow start which exposed Randall’s ruthless streak. Randall gave Wilkins a long list of photographs to prepare – for a backlog of papers that Randall was writing – and then told him to build his own apparatus for measuring luminescence. Then, just as Wilkins was getting into his stride during the last weeks of peace in summer 1939, Randall was called away urgently and left his new PhD student to cope on his own.

Figure 15.2 Maurice Wilkins (left), in discussion with Nobel Laureate Renato Dulbecco.

Randall’s new project was funded by a massive government grant which Oliphant had won against Lawrence Bragg, recently installed as Director of the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge. It was classified top secret. The aim was to make a powerful, accurate radar system small enough to fit in an aeroplane; a stroke of genius was required, as the existing equipment weighed a couple of tons and filled a large room.

Oliphant was impressed by Randall’s ability to think unconventionally and put him on the case, assisted by Harry Boot, a research student who, as a schoolboy, had built a Van der Graaf generator in his bedroom. The inspiration for the cavity resonance magnetron came from a second-hand book about the invention of radio, which Randall read while on holiday in Wales. The magnetron works on the same principle as an acoustic guitar, which is also a cavity resonator; substitute surges of electrons for the vibrations of the strings, and the holes drilled in the copper cylinder for the sound-box, and you have the basic concept for the ‘valve’ which Randall and Boot put together during the winter of 1939–40. The prototype was first tested on 20 February 1940, and immediately showed promise. A brilliant arc appeared around the business end; neon tubes several feet away burst into light without being switched on; a cigarette could be lit by bringing it close to the invisible beam; and the hand holding the cigarette became worryingly warm. Hundreds of prototypes later, they had a magnetron which blasted out microwave radiation that was 500 times more powerful than existing radar valves. It could see through cloud at night and pick out an aircraft over 200 miles away, a battleship at 60 miles and a surfaced U-boat at 30 miles – and it could fit into a night fighter.

Of all the tricks in Tizard’s black box, it was the Randall-Boot magnetron which captivated the Americans at that crucial moment in September 1940. During the war, American factories made over a million magnetrons for ships, aircraft and artillery. The device was decisive in winning the battles in the skies above Britain and Europe. No wonder that the Director of the US Office of Strategic Services described the magnetron as ‘the most valuable cargo ever to reach our shores’.

Meanwhile, back in Birmingham, Randall’s abandoned PhD student was having to manage by himself and was discovering that he thrived on neglect.

Lost soul

Maurice Wilkins was the middle of three children and a New Zealander by birth. His parents were Dubliners, with academics on his father’s side and a grandparental marriage which disintegrated so spectacularly that it was mentioned in Ulysses. New Zealand beckoned because his father, a school doctor, became bored with Ireland. He took his family to Pongoroa, set in rolling hills on the North Island, where Maurice was born ten days before Christmas 1916. The new baby was christened in a large silver bowl which his father had won as a cycling trophy.

Maurice enjoyed seven colourful years in the ‘Garden of Eden’ before his father fell out with ‘the authorities’ and took the family on a year-long ‘world cruise’ which ended with a new job in Birmingham. This was within striking distance of the Welsh mountains, where father and son continued their ‘Worship of the Hills’, walking and climbing at weekends. There were early hints of where Maurice’s curiosity might eventually take him. Aged twelve, he sketched the imaginary Radium Island, in the middle of the South Pacific and rich in uranium ore. Two things that he held dear were ingrained in childhood: an ‘almost religious’ reverence for science, and anger, inherited from his father, over the ‘poverty in the midst of plenty’ which the Depression was laying bare. He was also fascinated by optics, and hand-ground the lenses for his home-built but professional-quality astronomical telescope.

He won a scholarship to the local High School and nobody was surprised when, in 1935, he carried off an Entrance Scholarship at St John’s College, Cambridge to read Physics. Cambridge was more of a culture shock than he had expected – ‘great big buildings like citadels’ and a paranoid fear of ‘many clever people’. His first two years went smoothly, if not brilliantly. Best of all were the tutorials with Mark Oliphant, Rutherford’s right-hand man at the Cavendish who was about to be poached to the Chair in Physics at Birmingham. A major disappointment was J.D. Bernal, crystallographer extraordinaire, who relied on his ‘awesome charisma’ to carry him through his lectures; he would arrive late and stand enigmatically at the front for some minutes, reading a book.

Wilkins had been looking forward to the third year and Crystal Physics, but it was a catastrophe. The first dozen pages of his notebook show no hint of trouble; then several pages are torn out and the rest are blank. Wilkins’s melt-down was due to politics, ‘the most significant aspect of my Cambridge experience’. He had joined the Communists, led locally by Bernal who had often been a VIP visitor to the Soviet Union before the war. Disguised as ‘John J. Johns’ (in case university apparatchiks did not share his views on public engagement), Wilkins wrote a regular science feature for the Young Communist League’s magazine. He took to the streets in London under the banner, ‘Scholarships, not battleships’, and was the only undergraduate to join the Cambridge Scientists Anti-War Group. This group, also led by Bernal, was genuinely underground; they met in the basement of a café on King’s Parade, while the corrupt bourgeoisie enjoyed lunch above their heads.

Wilkins realised too late that Crystal Physics demanded more effort than ‘The secrets of the stars’ by John J. Johns, especially when he was summoned to explain why he had been writing ‘popular science for a left-wing youth paper’. What he called ‘my breakdown’ was diagnosed as a bout of depression. The result was the ‘very big shock’ of his 2:2 in Physics, which dashed any hope of doing research in Cambridge. The previously friendly Bernal now conspicuously kept his distance. As Wilkins later said, ‘I had to leave.’

Luckily, his prospects picked up after his phone call to Mark Oliphant in Birmingham. Wilkins’s first impressions of John Randall were strongly positive – ‘a small, upright man with clear, bright eyes and a lively energetic personality . . . full of interesting ideas about research . . . informal and ready to talk freely, even gossip, even about personal problems’. And Oliphant’s department, humming with both science and intrigue, was a thrilling place to be. When Wilkins called in to see Oliphant, he stubbed his toe on something heavy that had been dumped on the floor. It was a sack of uranium oxide.

And there was light

With Randall now working full-time and in secret on the magnetron, Wilkins was left to push ahead with his PhD unsupervised. He found the working conditions ideal: a compelling problem, the excitement of breaking completely new ground, a blank instruction sheet and nobody breathing down his neck. He made remarkably quick progress.

The Ministry of Home Security had moved on from its original bright ideas about applications for phosphors (e.g. making luminous collars to facilitate dog-walking during the blackout). Wilkins’s task, classified top secret, was to enhance the shining dot that marked the position of enemy aircraft on radar screens. Along the way, he wrote three masterly papers which killed off the current theory of phosphorescence and provided a convincing alternative. His work was described as ‘brilliant’ by one of the world’s leading theoretical physicists. With Oliphant’s approval, Wilkins added a punchy introduction and submitted the papers as his PhD thesis, a year early.

The PhD also taught him valuable lessons about life in general and John Randall in particular. Wilkins included Randall as co-author on one paper but not the other two, because he had nothing to do with them. Randall insisted that his name must be on all three. Wilkins was ‘very disturbed’ by the injustice – and took himself on ‘a long, slow wartime rail journey’ back to Cambridge, to consult the psychologist who had helped him through his depression. He was advised to let the boss have his way, as his career might later depend on Randall’s goodwill. Learning point for Wilkins: ‘I could not take it for granted that Randall would always act in my best interest.’

Apart from the friction over authorship, Wilkins’s relationship with Randall remained cordial. They and Henry Boot – who had been in the year below Wilkins at school – used to meet for lunch at the Students’ Union. The Official Secrets Act prevented discussion about the magnetron, but Wilkins had a rough idea of what was going on and could not help noticing the large horn-shaped structure which appeared on the roof above Randall’s lab.

After his PhD, Wilkins found himself at a loose end and on the receiving end of night bombing raids. His growing hatred of the Nazis caused a transformation that would have been unthinkable to the idealistic and naive ‘John J. Johns’ back in the ‘small world’ of the Cambridge Scientists Anti-War Group. Maurice Wilkins went to ask Oliphant about joining another project, even more secret and infinitely more destructive.

New World

Oliphant’s top project was cloaked in the camouflage of ordinariness. It was called ‘Tube Alloys’, a name chosen to be ‘meaningless, but with a specious feasibility’. Its origin was an eight-page document – the ‘Frisch-Peierls memorandum’ – that went to America in Tizard’s black box. Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls were both Jewish physicists who fled Germany in 1939 and came to Birmingham to work on nuclear fission. They theorised that fission could ‘go critical’ with just a few kilograms of a rare isotope of uranium that had an atomic weight of 235 (235U). Accordingly, the Tube Alloys project was set up to make the world’s first nuclear bomb.

Wilkins joined Tube Alloys in 1941. Oliphant set him working on the make-or-break problem of how to separate 235U from the non-explosive 238U, which makes up over 99 per cent of natural uranium. Wilkins’s brief was to turn uranium, normally a silvery metal as dense as gold, into a gas and to concentrate 235U using a diffusion barrier perforated with millions of tiny holes. He tried hard, with an array of bright steel tubes that passed through the ceiling of his lab and up one wall of the lecture theatre above, but two years later had got nowhere. In October 1944, it was decided on high that Oliphant’s team should move to the Radiation Laboratory at Berkeley, California, where facilities were better and time was not wasted by air-raids and power cuts. The ‘Manhattan Project’, as the American atom bomb programme was called, was a vast operation employing 130,000 people, all carefully parcelled up in ‘the greatest secrecy’.

Wilkins’s method still failed to produce useful quantities of 235U, but California was a fair swap for the edgy grey austerity of Birmingham. Instead of grabbing lunch with Randall and Boot in the Students’ Union, Wilkins could now enjoy a sandwich while looking across to the Bay Bridge and talking philosophy with new friends. And there was a woman in his life – Ruth, an art student who was bright, witty and shared his political views. They quickly ‘became close’. So close that Ruth fell pregnant; that Wilkins said they must keep the baby and get married; and that she agreed.

Summer 1945 was frantic for the Manhattan Project and life-changing for Wilkins. The first significant moment was when Harrie Massey, one of Oliphant’s team, gave him a book by Erwin Schrödinger, who had won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1933 and escaped from the Nazis a few years later. The book was small, but its title posed a huge question: What is Life?

It was the distillate of lectures that Schrödinger delivered in July 1944 at Trinity College in Dublin, where he was Director of Theoretical Physics. These lectures were a sensation: packed out every night with people off the streets as well as academics, dignitaries and the press. Schrödinger set out to demystify the processes of life by making them conform to the laws of quantum physics. His most famous sound-bite was the claim that genes are ‘aperiodic crystals’. Although he never explained what that meant, many believed that Schrödinger was a new messiah, bringing the hard clarity of physics to the anarchy of biology. Others found him unconvincing, like an oracle whose utterances had to be interpreted by the faithful.

Maurice Wilkins was one of those immediately seduced by the beauty of the writing and the power of the intellect that lay behind it. Genes and chromosomes had never crossed his path before. Suddenly, he was captivated by the thought of guiding his kind of science into the messy biological arena of genes and heredity. Schrödinger’s ‘aperiodic crystals’ rang a strangely familiar bell; the concept seemed ‘remarkably like the luminescent crystals I had studied before the War’. For now, though, he had work to finish, and ‘aperiodic crystals’ and genes were pushed into hibernation.

*

Around this time, Wilkins heard from John Randall, whom he had left behind in Birmingham. Randall had been through a rough patch and was unhappy and bitter, because the magnetron had left its inventors high and dry. The Americans had made off with it, modifying the design so that it could be mass-produced by American companies. The Admiralty, which funded Randall’s part of the radar programme, did not apply for a patent until January 1943, by which time the US Patents Office had already challenged the claim that Randall and Boot had invented it.

On top of that, Randall’s Royal Society Fellowship had run out, and even though he was the technological equivalent of a war hero, it was not extended. In desperation, he accepted an offer from Lawrence Bragg at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge for ‘half-time employment as a temporary lecturer’, with an absurdly heavy teaching load, no time for research and half his Fellowship salary. But it was better than the dole, so he moved to Cambridge in October 1943.

He and Harry Boot remained in touch while lawyers on both sides of the Atlantic continued wrangling over patents. In late summer 1944, Boot wrote with a pessimistic update, signing the letter ‘Harry (£££)’. He added a PS: ‘I’m afraid I haven’t yet got used to your new title’. Randall’s new title was ‘Professor’. He had escaped the menial teaching post at the Cavendish and moved north of the border, to the Chair of Natural Philosophy (Physics) at the University of St Andrew’s. He settled in quickly and started shaking the place up. And as soon as he had cobbled together enough money, he contacted his former PhD student, Maurice Wilkins, and offered him the post of lecturer.

Over in California, Wilkins’s relationship with Ruth had flourished after its first real test – the discovery that she was expecting their child. The second test came when Randall’s offer arrived. Wilkins turned that one down, but not the one that followed, with an increased salary offer. The war in Europe had just ended, and Ruth seemed to welcome the prospect of moving to Scotland. ‘I like rain,’ she said, and Wilkins began looking forward to returning to Britain with his wife and new baby.

Two bolts from the blue ruined his last few weeks in Berkeley. The first was a message from Ruth to go to a lawyer’s office, where he was presented with a $200 bill and their divorce papers, ready for him to sign. Wilkins was devastated and tortured himself with the thought that he should have ‘discussed the implications of marriage more thoroughly’. Ruth gave birth shortly after the divorce; her ex-husband saw his son once in hospital before she left Berkeley with the baby.

Then, on 6 August 1945, the news broke that Hiroshima had been destroyed by the atomic bomb nicknamed ‘Little Boy’. Like everyone else outside the Manhattan ‘Executive Board’, Wilkins had been kept perfectly in the dark. He did not know that the prototype – ‘Trinity’ – had been tested successfully in the deserts of New Mexico on 16 July. The news blackout was impressive, given that the flash was bright enough to be noticed by a woman 150 miles away, who happened to be blind. Initially, Wilkins was infected by the ‘joyful sense of achievement’ that swept through Berkeley – until a philosopher friend, who ‘did not look very happy’, confessed that he had always hoped that the bomb would fail. Wilkins wrote later, ‘I felt rather small, and gradually the penny dropped. I said, “Yes, you’re right.”’

A few days after that, Wilkins was on the boat for England, alone.

War work

The stock question, ‘What did you do during the war?’, would have received strikingly different responses from the three fledglings who, back in 1928, had flown Sir William Bragg’s nest at the Royal Institution.

J.D. Bernal lived up to his polymathic reputation, enlivened by his sense of adventure and a total disregard for his own safety. During the Blitz, he worked out how to distinguish a dud bomb from one with a delayed-action fuse that was still ticking – stimulating J.B.S. Haldane to write (on the back of a menu), ‘Desmond Bernal / Is not eternal / He may not escape from / The next bomb’. Bernal went on to model the impact of an intensive air-raid on an English industrial city, choosing Coventry (with its cathedral as the primary aiming-point) some five months before it all happened for real. Later came a rough crossing to the Normandy beaches in a motor torpedo boat on the afternoon of D-Day, and a particularly close encounter with a bomb on D+l; and, via Babylon, experiments with depth-charges in the jungles of Ceylon.

Kathleen Lonsdale had a much quieter time. As a pacifist and conscientious objector, she refused to report for Civil Defence duties and spent some months detained at His Majesty’s pleasure in Holloway Prison – a valuable experience, she claimed, because it helped her communication skills.

Bill Astbury found the war irksome. His main contribution to the war effort was teaching navigation to trainee RAF pilots. His research suffered two direct hits in January 1941, when the Ministry of Labour and National Service wrote to him requiring Florence Bell and his lab assistant Elwyn Beighton to report for military service. Astbury replied robustly, insisting that both were engaged on work of national importance and were ‘irreplaceable’, but the Man from the Ministry (a certain C.P. Snow) was unmoved. Both were plucked out of X-ray crystallography and retrained as radio operators; even worse, Bell then married a US Army lieutenant who later carried her off to Washington. Astbury managed to continue some experimental work, including a heroic labour of love by Miss A.M. Melland, working in Cambridge, who spent thirty days stringing up a microscopic array of over 1,250 giant chromosomes from the salivary glands of midge larvae. The array was rushed to Leeds, X-rayed by Astbury during an air-raid – and yielded nothing of interest.

On 11 March 1942, the three received bad news. Their patriarch, the Old Man’, had died quietly in his flat above the Royal Institution. Sir William Bragg was still ‘in his full mental vigour’, although there had been mutterings because ‘his kindliness had led him to welcome certain ambiguous advances from learned bodies in Nazi Germany . . . which, in his goodness of heart, he took at face value’. A curious situation for a man who had refused to collect his Nobel Prize in person because ‘Germans would be there’.

Blast from the past

Back in July 1942, the Journal of Heredity had printed an unusual paper, which would have lifted the spirits of its readers. It was based on what a sprightly eighty-six-year-old man could remember about ‘a unique summer afternoon of two-thirds of a century ago’. The interviewee was C.W. Eichling, still sporting the neat beard and moustache that he had first grown for the special horticultural mission of his youth, and the article was entitled ‘I talked with Mendel’.

Eichling had gone on to much greater things following the nine-month trip through Germany and Austria which brought him to Brünn and the Abbey of St Thomas in the summer of 1878. After working as a travelling salesman for Roempler, the exotic plantsman of Nancy, he moved to New Orleans and set up his own business. Roempler withered on the vine, but Eichling flourished; his Illustrated Plant and Seed Catalogue ran to over 100 pages, and ‘Eichling’s Superior Flat Dutch Cabbage’ and his ‘First and Best Peas’ were second to none.

Now, Eichling ‘looked back over 64 years to give us a glimpse of the first geneticist’. His account of his day in the sun with the genial bespectacled priest was an enthralling read for anyone with the faintest interest in genetics. The old man had two regrets: that he had failed to entice the ‘Founder of Genetics’ to break his vow of silence about the ‘little trick’ to perfect the abbey’s peas; and that ‘other plans’ had prevented him from fulfilling his promise to visit Mendel again.

‘I talked with Mendel’ was published to coincide with the 120th anniversary of Mendel’s birth on 22 July 1822. It would have delighted Nikolai Vavilov, but it is very unlikely that he ever saw that issue of the Journal of Heredity. Almost two years since his disappearance, there was still no news about his fate.

Shortly after Eichling’s paper appeared, it was announced in London that Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov had been elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society. This rare honour was intended not only to recognise Vavilov’s achievements and to give him succour, but also to remind the Soviet authorities that the eyes of the global scientific community were on them. It was impossible to tell whether the message reached either of its targets; the Society later admitted that Vavilov ‘probably did not know’ of his election.

Strangely, Vavilov’s plight failed to excite one of the few Fellows of the Royal Society who might have been able to pull strings inside Russia. J.D. ‘Sage’ Bernal, elected FRS in 1937, had kept in contact with top-level Soviet scientists, and in his 500-page book, The Social Function of Science (1939), praised ‘the beautiful example’ of Vavilov’s ‘bureau of plant industry’ and his ‘very thorough development of genetic principles’.

But, being a loyal Communist, Bernal was careful not to rock the Stalinist boat. The ‘controversy on the foundations of genetics’ which engaged Vavilov and Lysenko was relegated to a footnote in his book. It was nothing to get upset about; just a minor spat that had been ‘magnified out of all proportion’ by the capitalists who wished to discredit Soviet science.