24

PHOTO FINISH

Maurice Wilkins spent most of January 1953 in limbo. Rosalind Franklin and Ray Gosling were still shut away incommunicado. The date had been fixed for Franklin’s farewell seminar – 28 January – but an attack of flu had delayed her departure and nobody knew when she would finally leave. Wilkins planned to re-form his DNA group as soon as she had gone, but to avoid trouble in the meantime, was keeping well away from X-ray crystallography. Instead, he had gone back to his microscopes. And while using them to measure the DNA content in individual chromosomes, he rediscovered why living things had lured him away from physics, and experienced again the forgotten pleasure of talking science with friends.

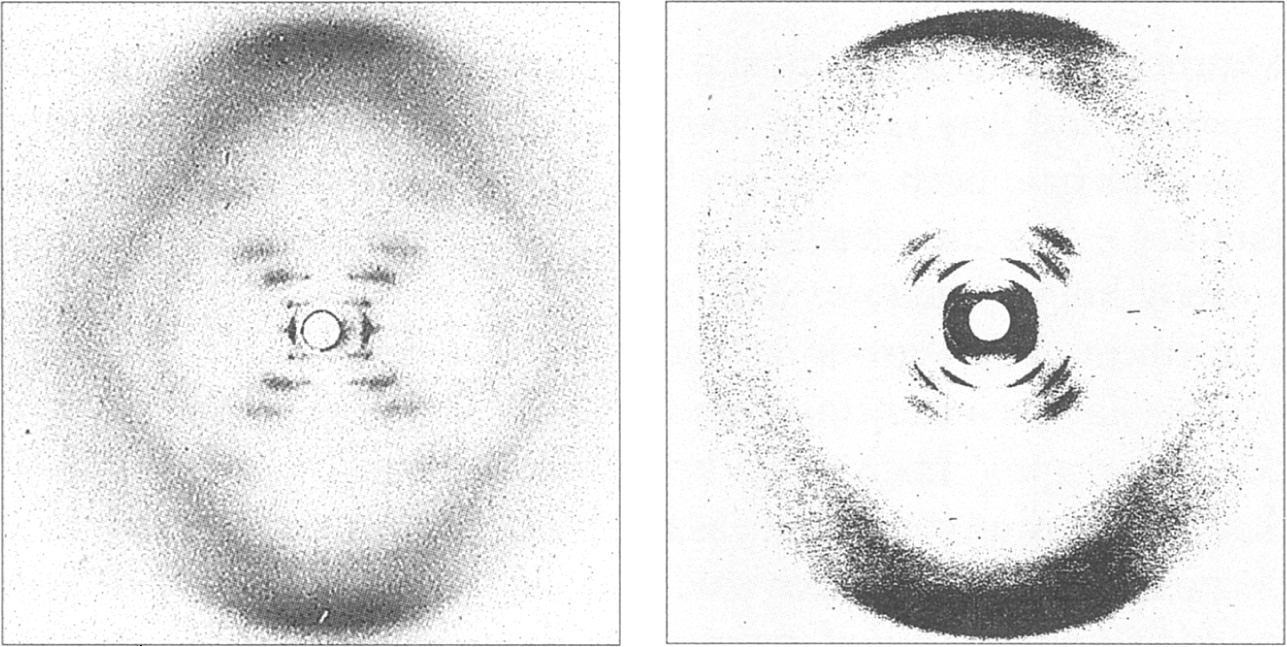

Something ‘extraordinary’ happened in late January. Without warning, Ray Gosling came to find Wilkins and presented him with an X-ray diffraction photograph from Rosalind Franklin. The image was as extraordinary as the act of being given it: a beautifully clear, capital X of the B form of DNA (Figure 24.1). Gosling insisted that it was for Wilkins, and that it was his to do with as he wished. He left Wilkins stunned.

The photograph had an intriguing provenance. It had been taken almost nine months earlier, with a sixty-hour exposure that began on the evening of 1 May 1952 when Gosling mounted some wet DNA fibres on the bent paperclip. This date should have been a red-letter day for British science. Bill Astbury had organised a one-day symposium on protein structure at the Royal Society, built around an eminent speaker from the USA. Unfortunately, the US State Department believed that it was not in America’s interest for the speaker, who had Communist leanings and was a security threat, to leave the country. They therefore refused Dr Linus Pauling’s application for a visa, leaving a massive hole in Astbury’s conference programme.

In retrospect, that day was also fascinating for a more parochial reason. Rosalind Franklin had been there, assailed by doubts about the A structure, and told Wilkins that DNA could not possibly be helical. Yet this photograph, taken that same evening, was shouting ‘Look at me – I’m helical!’ just as loudly as Wilkins’s original A image had declared its crystallinity.

Figure 24.1 X-ray diffraction images of the B form of DNA, showing the X-shaped pattern characteristic of a helical molecule. Left: Photograph 51. Right: Wilkins’s photograph of ‘orientated’ squid sperm.

This was the picture that Franklin indexed as ‘Photograph 51’. It became one of the iconic scientific images of the twentieth century and created a moment of high drama in James Watson’s Double Helix. However, Wilkins’s account of what happened to it was unsensational. He did nothing immediately, intending to wait until after Franklin had gone. A few days later, he recalled, Watson visited King’s, and Wilkins stopped him in the corridor and showed him the photograph. He did not record Watson’s reaction but noted that he ‘seemed to be in a hurry to leave’. Wilkins remembered saying that he thought that Chargaff’s base ratios were the key to the structure of DNA, and Watson replied ‘So do I’ as he dashed off.

Franklin’s farewell seminar on 28 January was ‘exceptionally long’ – an hour and three-quarters. She and Gosling had clearly put in a vast amount of effort, but Wilkins thought that ‘it did not add up’. She stuck religiously to the brief that Randall had given her – the A form, and nothing else – and talked at length about delving through the entrails of Patterson analyses to find the structures that made it crystalline. They had built a scale model in perspex of the supposed ‘unit cell’ of the crystal structure – ‘big enough to sit in’, as Wilkins said – but had no clear idea how the DNA molecules were packed into it, or what they looked like. The word ‘helix’ was not mentioned, and Photograph 51 never appeared on the screen. Afterwards, Wilkins asked her about the helical form that stood out in some of her photographs. That was the B form, she replied, and it was a helix; this one, the A form, was not. Taken aback by her sudden retreat from her ‘anti-helical’ position, Wilkins sat down and said no more.

Behind the closed door, Franklin and Gosling had finished studying the effects of water on DNA structure, which took them from their damp A form to the wet B that should have been Wilkins’s property. Now that she had extracted everything she needed from Photograph 51, she was happy to let Wilkins have it. It was a nice geste d’adieu- even if she could not bear to hand it to him herself.

After Franklin’s farewell seminar – and still with no indication of when she would actually go – Wilkins wrote a depressed note to Crick. ‘Rosie’s colloquium made me a bit sicker,’ he complained. ‘God knows what will become of all this business.’ He said he would scribble down what he could remember and pass it on. Wilkins also thanked Crick for the ‘almost daily shoal of letters’ asking him to stay in Portugal Place. At last, he could accept the invitation and looked forward, just as in the old days, to ‘a jolly, light-hearted weekend of sociability.’ He was to be cruelly disappointed.

Those waiting for him at the Cricks’ house were not Francis and Odile, but Watson and Crick. They began by handing him a typed manuscript and asking if he could see what was wrong with it. The manuscript was by Linus Pauling and Robert B. Corey of Caltech and reported their structure for DNA. This should have been a bombshell but Crick and Watson were upbeat and smug, obviously convinced that it was fatally flawed. Wilkins quickly scanned the structure – three intertwined helical strands with the phosphates innermost, just like the doomed Crick-Watson model of a year earlier – and then noticed that the chemical composition contained no sodium, which was always associated with DNA. He pointed this out and Crick exclaimed ‘Exactly!’, as though Wilkins ‘had shown special insight . . . like a schoolboy at an oral exam who happens to guess right’. This left Wilkins feeling patronised. Then Crick and Watson got down to the real reason they had summoned him to Cambridge.

Pauling was sitting pretty in Pasadena, certain that he had cracked the structure of DNA and still oblivious of the surprisingly basic blunders in his model. Crick and Watson had gained privileged access to the manuscript because Pauling had sent a copy to his son Peter, sharing their office in the Cavendish. The paper was soon to be published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science – when all the errors would stand revealed and an embarrassed Pauling would quickly be back in the race.

This left Crick and Watson just a few weeks to solve the structure and beat Pauling, so they wanted Wilkins to let them start building DNA models again. During the year-long moratorium, King’s had done nothing useful with DNA: no papers published, not even a consensus over whether or not it was a helix – and no models built with the templates which Crick and Watson had generously donated. Now, even Bragg wanted the Cavendish to pick up DNA again. Pauling had also sent him a copy of his paper ‘out of courtesy’, and Sir Lawrence was determined to avoid a repetition of his humiliation over the alpha-helix.

Wilkins was floored by their ‘horrible’ request and the prospect of a ‘London-Cambridge Rat Race’. He wrote later that ‘science had to march on’ and that he had ‘no alternative but to accept their position’. The promise of the ‘jolly’ weekend with the Cricks had evaporated. Disillusioned and angry, Wilkins got up to leave. Crick had ‘the sense not to press me to stay’ but Watson followed Wilkins out into the street and ‘expressed his regrets’. Wilkins was ‘not very receptive’, and went straight to the station.

Also-ran

John Randall heard about Pauling’s DNA model before Bragg, but without knowing any details of the structure. In early January 1953, he received a letter that Pauling had sent on the same day he posted his manuscript off to PNAS. Pauling first apologised for being too busy to attend a meeting that Randall was organising, and then added a coda that smelled of smugness and revenge – and reminded Randall of his refusal to share Wilkins’s DNA photographs. ‘Professor Corey and I are especially happy during this holiday season . . . we have discovered a structure of DNA which we have submitted for publication.’ He admitted that ‘our X-ray photographs are not especially good . . . but good enough to permit the derivation of our structure’.

Watson later wrote that Pauling’s ‘unbeatable combination of a prodigious mind and an infectious grin’ left many of his colleagues waiting quietly for ‘the day when he would fall flat on his face by botching something important’. Although Pauling did not know it, that day was fast approaching. His triumphant DNA structure was not just bad, it was dreadful. As well as the inside-out misplacing of the backbone and the absence of sodium which Wilkins had spotted, Pauling had invented hitherto unknown properties for the phosphate groups that supposedly made up the core. According to the laws of chemistry (which Pauling had helped to formulate), the molecule would not be acidic (despite there being a clue in the name, ‘deoxyribonucleic nucleic acid’), and the three strands could not be held together (one critic later said that Pauling’s structure would ‘explode’).

How could the brilliant Pauling, with his vast knowledge of chemistry, have made such elementary blunders? Wilkins later described his efforts as ‘pretty lamentable’ and suggested that ‘he just didn’t try’. Pauling was also the victim of his own furious drive to win yet another race, and in the process cut corners to a degree that causes ideas travelling too fast to skid out of control. For now, though, while his paper was incubating in press at PNAS, Pauling’s reputation was intact. And Watson and Crick were not going to spoil his peace by telling him where he had gone wrong.

Even before it was published, Pauling’s absurd model had important consequences. It whipped Watson and Crick into a frenzy, completed their transformation from collaborators with King’s into competitors, and drove a wedge between them and Maurice Wilkins.

This left them in a perilous situation. To build a new model, they needed hard data – molecular dimensions, angles, distances. Both men had done experiments with X-ray crystallography – Crick with proteins, and Watson with TMV – but they had no hands-on experience with DNA, which was a much greater challenge. Until now, all their structural information about DNA was second-hand, and almost exclusively filched from King’s. Crick had joked about their ‘burglary’ of results from Wilkins, Franklin and Gosling, but the ‘people at King’s’ saw no humour in their behaviour. And now they had estranged Wilkins, their only conduit of intelligence from King’s. Realistically, King’s would remain their sole source of inside knowledge about DNA. So how could they now get their hands on it?

This prompts us to revisit the day in February 1953, already described by Wilkins in rather bland terms (page 328), when Watson called into King’s and saw for himself the unmistakable ‘helical cross’ in Photograph 51. Watson’s story is radically different.

He had gone to London to see a friend at the Hammersmith Hospital, and had taken a copy of Pauling’s manuscript, which at that stage had only been seen by the inner circle at the Cavendish. On the way home, he diverted to King’s, intending to show Pauling’s paper to Wilkins. He was busy, so Watson decided to discuss it with Rosalind Franklin. He pushed into her office without knocking and found her busy measuring an X-ray photo on a light box; he noted that she was clearly not happy to be interrupted. Watson asked her if she wanted to see Pauling’s manuscript and then, rather than put her to the test as he and Crick had done with Wilkins, ‘immediately explained where Linus had gone astray’. He also pointed out that Pauling’s model, like their own, contained three strands of helical DNA. Franklin became ‘increasingly annoyed with my recurring references to helical structures’ and insisted that her own X-rays showed ‘not a shred of evidence for a helix’.

At that point, Watson ‘decided to risk a full explosion’, and ‘implied that she was incompetent in interpreting X-ray pictures’. This was the provocation that pushed her over the edge. ‘Suddenly Rosy [sic] came from behind the lab bench . . . and began moving towards me. Fearing that in her hot anger she might strike me, I grabbed up the Pauling manuscript and hastily retreated.’ At the door, he ran into Wilkins; as they walked away, Watson told him that his arrival ‘might have prevented Rosy from assaulting me’. According to Watson, Wilkins said that she had ‘made a similar lunge towards him’ following an argument some months earlier.

By Watson’s account, that shared experience ‘opened up Maurice to a degree that I had not seen before’. Wilkins told him that Franklin had been gathering evidence for a distinct structure of wet DNA that she called the ‘B form’. As this was news to him, Watson asked what the pattern looked like. Wilkins ‘went into an adjacent room’ and collected his print of Photograph 51. The effect on Watson was immediate and electric: ‘the instant I saw the picture, my mouth fell open and my pulse began to race’. Here was rock-solid evidence for a helix, and so clearly drawn that all its vital statistics could be derived.

Wilkins then took Watson for another supper in Soho. Despite a bottle of Chablis and unrelenting interrogation by Watson, Wilkins avoided revealing the exact dimensions of the helix, or how many chains he thought were intertwined, or how the bases might be brought together.

On the train home to Cambridge, Watson sketched what he could remember of the big black X on the margin of his newspaper, and tried to decide whether the structure contained three chains – still the general assumption – or only two. By the time he had cycled back to Clare College and climbed over the back gate into Memorial Court, he had made up his mind to go for two chains, and that ‘Francis would have to agree’.

On the quiet

Early March 1953, and the tempo was quickening at King’s. Unusually restless, Maurice Wilkins was feeling ‘the pressure of necessity’ and had a premonition of ‘history in the air’. The sense of urgency was heightened because he had heard nothing from Cambridge since Watson’s visit to King’s at the end of January.

Wilkins had been thinking about Chargaff’s mysterious ratios and the possible significance of A = T and C = G. He wondered whether these pairs of bases could be physically linked in the DNA molecule, and mentally sketched out a structure in which the pairs of bases lay in the same horizontal plane, as if on a tabletop, perpendicular to the long axis of the molecule. They formed the core of the structure, but he could not see how they would be tied together – and the cumbersome edifice which hovered in his imagination contained not two or three helical strands of DNA, but four.

On the practical side, he was at last mobilising his troops. Franklin’s departure was now imminent, and Randall had given his approval for a full-frontal assault on DNA. Alex Stokes rejoined the campaign, and two other crystallographers – Bill Seeds and the heavy-duty Herbert Wilson – came on board. Wilkins had found another source of top-quality DNA, which was fortunate, as he was about to discover that Franklin and Gosling had used up the last of Signer’s stock. He had visited Harriet Ephrussi-Taylor in Paris, where the photograph of Oswald Avery smiled benignly down on them from the wall of her office. Appropriately enough, Ephrussi-Taylor extracted her DNA from bacteria (E. coli as well as pneumococci) and had shown that it had the power to transform. Back at King’s, this ‘real live genetical material’ behaved as impeccably as Signer’s, yielding a beautiful ‘helical cross’ B pattern identical to that in Photograph 51.

On Saturday 7 March, Wilkins wrote to ‘My dear Francis’ – a salutation that he later admitted felt awkward. The top news – ‘I think you will be interested to know that our dark lady leaves us next week’ – meant that Wilkins was now making up for lost time. ‘Most of the three-dimensional work is already in our hands . . . the decks are clear and we can put all hands to the pumps [for] a general offensive on Nature’s secret on all fronts: models, theoretical chemistry, X-ray crystallography.’ He ended, ‘It won’t be long now . . . Yours ever, M.’

Wilkins may have hoped to subdue Crick and Watson with this display of superior firepower, especially as they could not generate any data of their own and relied on crumbs scavenged from King’s. However, his letter had the opposite effect when Crick opened it on the morning of Monday 9 March. Wilkins’s prediction that ‘it won’t be long now’ was painfully accurate, because Cambridge had already won the rat race.

In fact, Watson and Crick were already back in the running when Crick invited Wilkins up to Cambridge to extract his blessing to their resumption of model-building. On the morning of Saturday 31 January – the day after his confrontation with ‘Rosy’ and supper with Wilkins in Soho – Watson had taken his case to the top. Sir Lawrence Bragg listened to the evidence, agreed that the moratorium must end, and gave Watson permission to drop his TMV work and build models of DNA. Crick could also contribute, while finishing off his PhD on proteins.

Watson took his designs for the purine and pyrimidine templates, to be cut out of tin sheet, down to the Cavendish’s machine-room and was told that the work would take a couple of weeks; a few days more were needed because he forgot to order the phosphorus atoms. Initially, Watson worked in a dispiriting knowledge vacuum. ‘No fresh facts came to chase away the stale taste of last winter’s debacle’ – their disastrous inside-out model of December 1951 that had provoked Bragg’s moratorium. Watson complained that ‘Francis and I remained closed off from the experimental data’. An alternative interpretation is that they had ridden roughshod over a former friend and collaborator and had severed their links with the only place on the planet capable of generating the information that they needed to move on.

Fortunately for them, that embargo was soon broken, with the gift of a crucial nugget that Franklin and Gosling had dug out during their months of Patterson analyses on the A form. This was a string of numbers describing the ‘space group’ which gave the A form its crystalline appearance, together with its crystallographic designation, ‘C2’. This meant nothing to Watson, and despite her years of experience, Franklin also missed its significance. But Crick had met ‘C2’ before, deep in the structure of horse haemoglobin, and knew that it could represent a structure containing two chains that ran in opposite directions. This was powerful evidence that DNA consists of two strands, and the ‘anti-parallel’ configuration (one strand running ‘up’ and the other ‘down’) later proved essential in understanding how DNA works.

This breakthrough fired up Watson and Crick with new energy for their attack on the two-chain model of DNA. As this took shape, it could be ‘checked directly with Rosy’s precise measurements’. Watson later admitted that ‘Rosy, of course, did not directly give us the data . . . For that matter, no one at King’s realised they were in our hands.’ Max Perutz had come to their rescue. As a member of the MRC Biophysics Committee, he had been on the annual site visit to King’s back in December and had just received his copy of the progress report, which included Franklin’s calculations on the A structure. Perutz saw nothing wrong in handing the report over to Watson and Crick.

Even though Franklin had explained at length why the phosphate-sugar backbones could only be on the outside of the DNA structure, Watson began by putting them at the heart of his new two-strand model. He persisted for some days (breaking off periodically to play tennis), even though the results ‘looked stereochemically even more unsatisfactory’ than their previous effort. Then, over supper in the Cricks’ basement dining room, Crick suggested putting the phosphates outermost; the next morning, while contemplating a ‘particularly repulsive backbone-centred model’, Watson at last picked up Franklin’s cue.

He constructed a short section of two helical backbones of phosphate-sugar, like one turn of a spiral staircase but with all the steps missing. There was a void up the middle because the machine-shop had still not delivered the tin-plate cutouts of the bases. That void could be filled with a spiral stack of steps consisting of pairs of bases, one attached to each backbone, but there was an obvious problem. The overall shape of DNA had to be a smooth cylinder, but because the two-ringed purines (A and G) were larger than the single-ringed pyrimidines (C and T), the steps made of pairs of bases would have unequal widths. The backbones would have to bulge outwards to accommodate the widest steps (purine-purine), and be pulled in around the narrowest (two pyrimidines). The outline of DNA would not be cylindrical but lumpy, like a python that has swallowed rats of different sizes.

It was at this point that Wilkins had come to Cambridge, naively believing that this would be a weekend of bonhomie and gastronomy with Francis and Odile. After their discussion turned sour, Watson followed Wilkins out into the street to apologise, but his later account of the visit does not show much remorse. ‘Maurice’s slow answer emerged as no, he wouldn’t mind our building models . . . Even if his answer had been yes, our model-building would have gone ahead.’

And so Watson continued, interrupted by tennis, popsies, sherry parties and a trip to the local fleapit to see the heavily censored Ecstasy. There were still no templates from the machine-room, so Watson copied out the structures of the bases from Norman Davidson’s benchtop bible, The Biochemistry of the Nucleic Acids, and cut their shapes out of stiff card so that he could try to fit them together on his desk. Somehow, he and Crick had forgotten about John Griffith’s prediction that specific pairs of bases could be pulled together by hydrogen bonding. Now, Watson thought about hydrogen bonding again and, as Crick had done, first wondered whether each base could attract itself. He spent an excited night awake ‘with pairs of adenine residues whirling in front of my closed eyes’, only for that notion to be ‘torn to shreds’ the next morning by Jerry Donohue, the American crystallographer who now shared their office.

It was Donohue who gave Watson the crucial nudge which finally set him off down the short but thrilling home straight to the winning post. Each of the bases exists in two chemical forms, thanks to a hydrogen atom which can dodge from one position on the molecule to another; this switch instantly changes the anchor-points for hydrogen bonding. Watson had copied out the bases’ structures from Davidson’s book, which showed an odd selection of the two forms. Donohue’s winning tip was to use just one version – the ‘keto’ form – which according to recent research was the one that occurred in real life. Watson spent the afternoon redrawing the keto versions of the bases and fiddling with his card cutouts, but the bolt of inspiration did not hit him until he had slept on it all.

First thing the next morning, Saturday 28 February 1953, Watson cleared a space on his desk for his card cutouts and began sliding the shapes around. This unleashed not just a eureka moment, but a string of them.

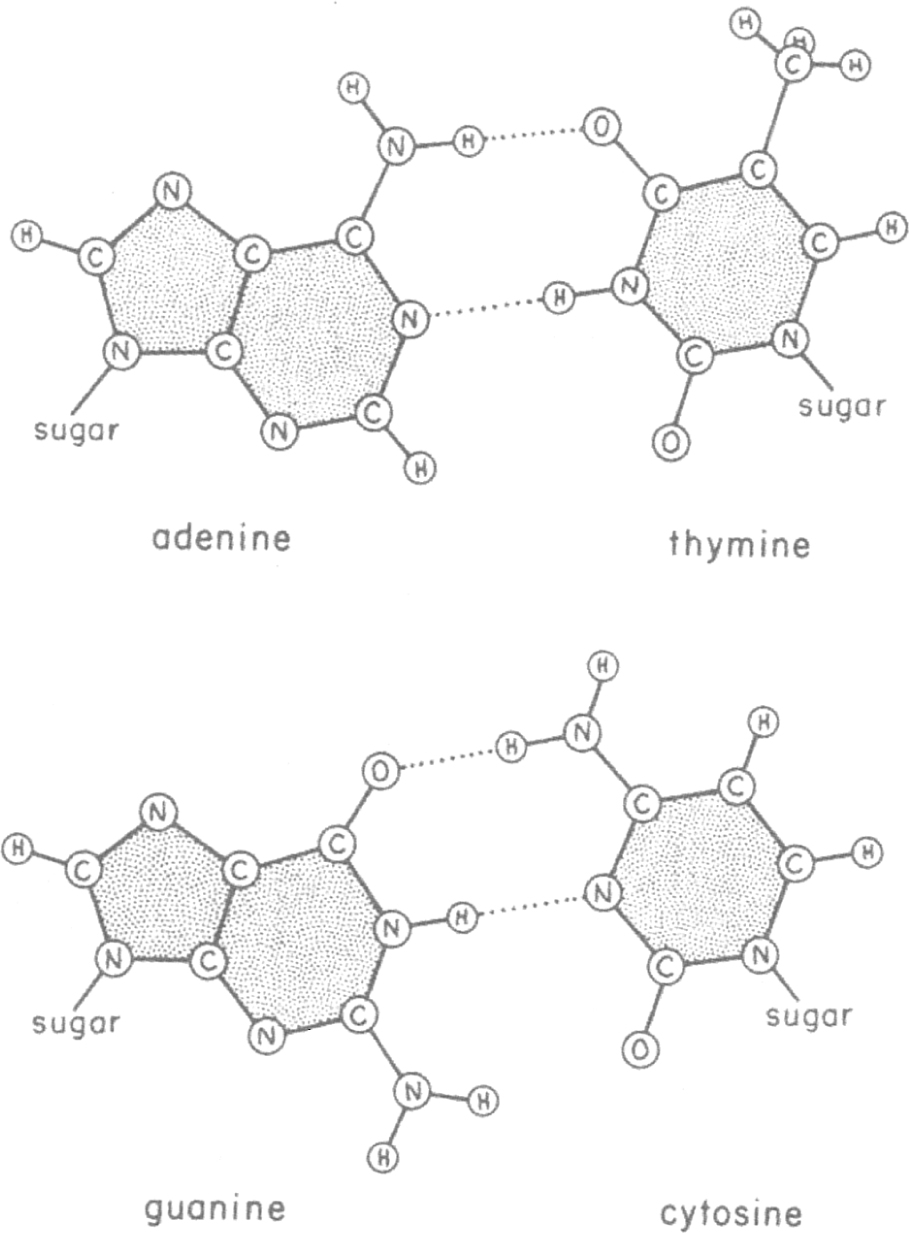

‘Suddenly, I became aware that an adenine-thymine pair held together by two hydrogen bonds was identical in shape to a guanine-cytosine pair.’ The hydrogen bonds lined up naturally, ‘with no fudging required’ (Figure 24.2). Instantly, Chargaff’s rules – A = T, C= G – made perfect sense, and a mechanism to explain how DNA replicated itself sprang into his mind. ‘It was thus very easy to visualise how a single chain could be the template for the synthesis of a chain with a complementary sequence.’

As soon as Jerry Donohue arrived, Watson made him check the structures; he found ‘no objection’ and Watson’s spirits ‘skyrocketed’. And when Crick turned up, he only got halfway through the door before Watson ‘let loose that everything was in our hands’. They spent the morning trying to find errors in Watson’s scheme, and failed. Elated, they adjourned to the pub for lunch. Watson later wrote that he felt ‘slightly queasy’ when ‘Francis winged into the Eagle to tell everyone within hearing distance that we had found the secret of life’.

Figure 24.2 Hydrogen bonding (dotted lines) linking adenine with thymine and cytosine with guanine, to bridge the two helical strands of DNA. It was later realised that there are three hydrogen bonds between cytosine and guanine.

Crick’s recollection of these momentous events diverges in places from Watson’s. The revelation about base-pairing was, according to Crick, a simultaneous and shared experience: ‘Jerry and Jim were by the blackboard and I was by my desk, and we suddenly thought, well perhaps we could explain the 1:1 ratios by pairing the bases . . . At that point, all three of us were in possession of the idea . . . It was the next day that Jim came in and did it.’

And sadly, Crick had ‘no recollection’ of that glorious moment when he supposedly informed the lunchtime drinkers in the Eagle that they had solved the mystery of life. He did, however, remember telling Odile that they had made a ‘big discovery’, but as he was forever saying things like that, she thought nothing of it.

Bragg was in bed with flu when he heard the news but was ‘immediately enthusiastic’ and instantly became ‘one of our strongest supporters’. The machine-room was slower to respond. The metal base templates were not delivered until the first week of March. Four days of frantic but painstaking work on the model followed, building-block by building-block, and then checking the position of each atom. When they finished on the morning of Saturday 7 March, Crick ‘just went straight home and to bed’.

They were back in the lab on the morning of Monday 9 March. Their model was standing on the bench top in Crick’s line of sight as he opened the letter from Maurice Wilkins which began ‘My dear Francis’ and went on to tell him that ‘the dark lady’ was leaving and that ‘It won’t be long now’. Neither Crick nor Watson had the heart to break the news to Wilkins, so they asked someone else to do it.

Scooped

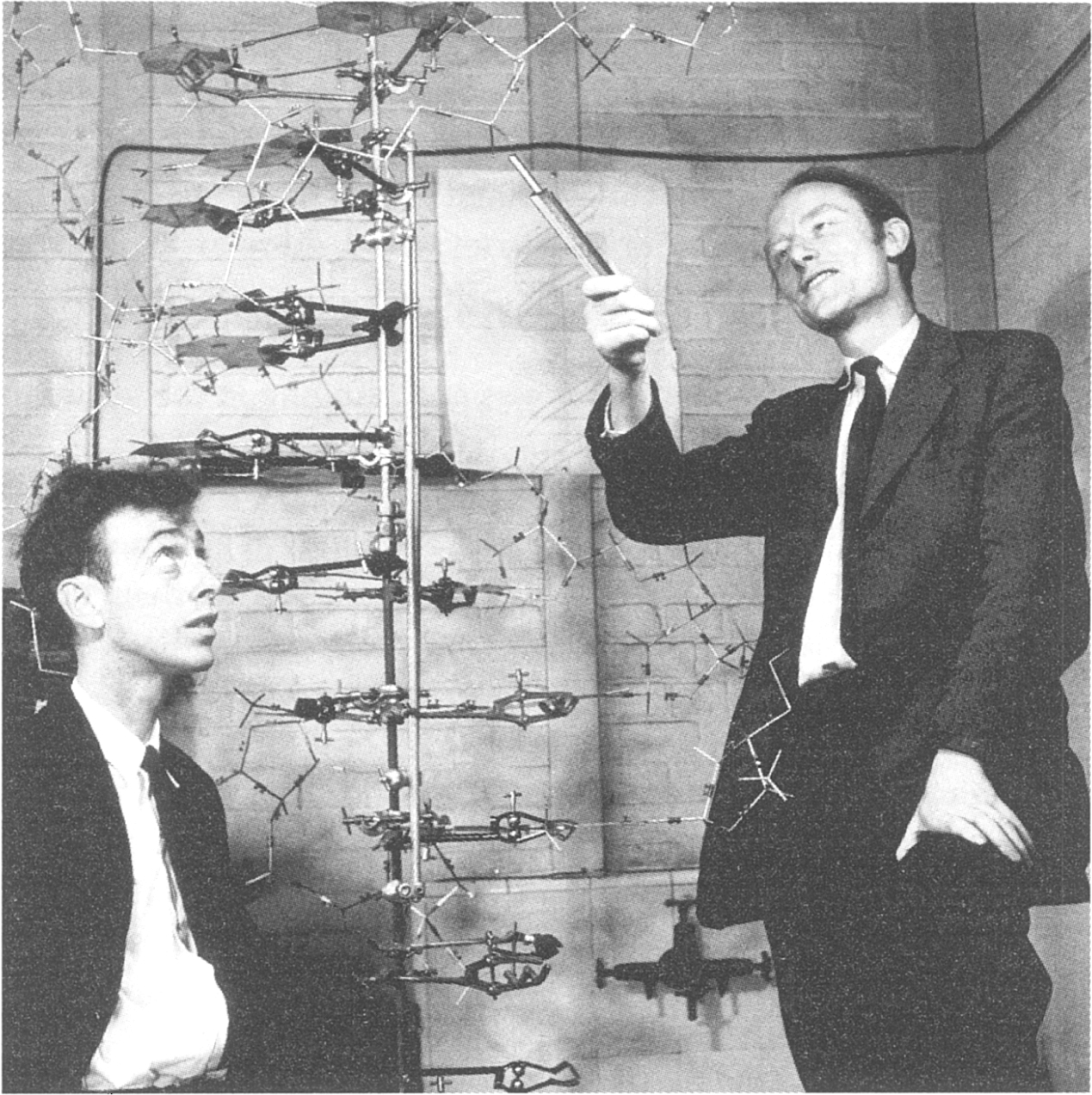

On Thursday 12 March, John Kendrew rang Maurice Wilkins and invited him up to the Cavendish to see the new Watson-Crick model of DNA. Kendrew revealed little – two strands, held together by hydrogen bonds between pairs of bases – but Wilkins instantly felt ‘tension in the air’ and was ‘on a train to Cambridge straight away’.

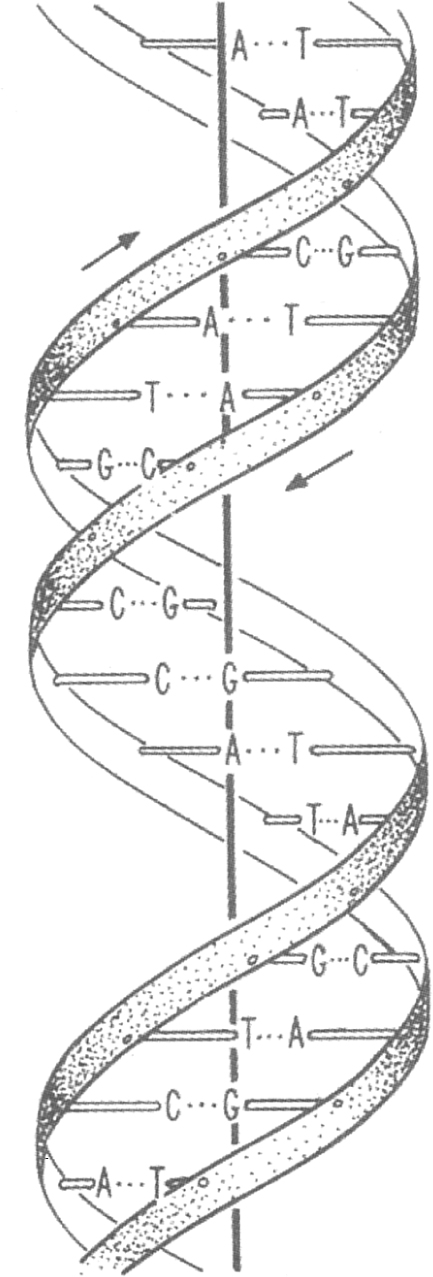

The model was almost six feet high, even though it only represented a single turn of the double helix (Figure 24.3). Gazing up at it, Wilkins saw some familiar features – the helical backbones of sugar-phosphate spiralling vertically and placed outermost, with the bases lying horizontally in the core of the structure. There were also some alien touches – only two strands of DNA, not three, and a stroke of pure brilliance in the construction of the steps in the spiral staircase. All the steps were identical in width, because an adenine joined to a thymine by hydrogen bonds is precisely the same length as a cytosine linked to a guanine. This meant that the two backbones spiralled evenly around each other, always the same distance apart.

Figure 24.3 Jim Watson and Francis Crick with their model of the double helix, April 1953.

Watson watched Wilkins, lost in thought, while Crick talked non-stop about the unique features of the double helix. Watson had feared some sort of backlash because, as he put it, ‘we had seized part of the glory which should have gone in full to Wilkins and his younger colleagues’. But, according to Watson, Wilkins looked at the model and then went back to London ‘with not a hint of bitterness’. Either Watson or his memory edited out an unpleasant exchange that Wilkins later described as ‘an angry outburst’. This came when Crick and Watson asked Wilkins, still contemplating the double helix, if he wanted to be the third author on the paper which they were writing for Nature about their structure.

Until that moment, Wilkins had been ‘rather stunned’ by the model, which to him seemed to say, ‘I know I am right.’ Their question about co-authorship brought him back to earth with a nasty bump. He realised how ‘possessive’ he felt about DNA and the ‘deeply satisfying times’ it had given him – and also how much of the model was derived from ‘work done at King’s’. Instead of thanking them for their offer, Wilkins made clear his bitterness, which Crick told him was ‘unfair’. The untouchable question of who had done what was still hanging in the air when Wilkins left to return to London.

At King’s the next day, Wilkins told ‘everybody’. There was general dismay and anger that Crick and Watson had got there first, especially as they had done none of the experiments themselves. Ray Gosling was ‘quite upset at being scooped’, while Randall was as furious as ‘a scalded cat’. After the weekend, Gosling took the news to Rosalind Franklin, who had finally packed her trunk and said goodbye to the circus, and was settling in on her first day at Birkbeck. She reacted with equanimity: ‘We all stand on the shoulders of others.’ And then, even though Randall had barred her from working on DNA or with Gosling after leaving King’s, she and Gosling sat down to revise a manuscript which had been in preparation for the last month.

They had finished their big paper on the influence of the water content of DNA in mid-February. On 23 February, Franklin’s lab book shows that she had dug out her own copy of Photograph 51. This was forbidden fruit, because Randall had allocated the B form to Wilkins, but she now began to analyse it in detail. She quickly concluded that it was indeed helical – and decided, from the new data, that it must consist of two strands, not three. From her lab book entries, it is clear that she was convinced that Chargaff’s base ratios were significant, but she stopped short of spotting that a purine would pair up with a pyrimidine – the revelation that could have led her to the double helix ahead of Watson and Crick.

But now, armed with the information about the model that Wilkins had brought back from Cambridge, she could check to see whether it fitted the Patterson analyses that she and Gosling had laboured over for months. She and Gosling set to work.

On Wednesday 18 March, Wilkins received a copy of the draft paper from Francis Crick. He read it carefully, then sat down and dashed off a reply. ‘I think you’re a pair of old rogues,’ he wrote, ‘but you may well have something. I like the idea.’ Wilkins made a watered-down reference to his ‘angry outburst’ in front of the model. ‘I was a bit peeved because I was convinced that the 1:1 purine pyrimidine ratio was significant and as I was back on helical schemes I might, given a little time, have got it.’ Philosophically, he added, ‘But there is no point grousing. It’s a very exciting notion and who the hell got it isn’t what matters.’ Nonetheless, King’s deserved recognition for all that they had done. ‘We would like to publish a brief note with a picture showing the general helical case alongside your model. I can have the whole thing ready in a few days.’

At that point, Wilkins broke off, only to return to the letter a short while later. ‘Just heard this moment of a new entrant to the helical rat-race.’ Franklin and Gosling had contacted him because they had already written a paper, or as Wilkins put it, ‘served up a rehash of our ideas of 12 months ago’. His ill-feeling against Franklin had apparently evaporated. ‘It seems that they should publish something (they have it all written). So at least three short articles in Nature. Christ!’ He signed off, ‘As one rat to another, good racing. M.’

Things moved very rapidly through the end of that week, at various levels. Up in the stratosphere, civilised words were exchanged over lunch in the Athenaeum between John Randall and the joint editors of Nature, Jack Brimble and Arthur Gale, and a gentlemen’s accommodation was swiftly reached. King’s would be given a few days’ grace to write up their two papers, and all three would appear as a job lot in Nature on 25 April 1953.

Meanwhile, down on the shopfloor, there was a frenzy of writing and rewriting. On Monday 23 March, Wilkins scribbled a note to Crick, complaining that he was ‘so browned off with the whole madhouse that I don’t really care much about what happens’. His paper, co-written with Alex Stokes and Herbert Wilson, was ready to be sent to Nature. So was ‘Rosie’s thing’ – an alternative analysis of the B form (Wilkins hoped that the editors would not ‘spot the duplication’) which, as Gosling later said, showed ‘to our great satisfaction and delight’ that it fitted beautifully with a two-chain helical structure.

King’s won the last-minute scramble to finish and send off the papers. On Thursday 26 March, Wilkins wrote an elated postcard to Crick: ‘You will be relieved (I am) to hear that all is safe in the hands of Gale.’ This was despite ‘a frantic rush at the last moment: no typist and two missing figures which after a long search turned up in Randall’s bag and in Rosie’s room’.

Typists were also in absentia at the Cavendish a couple of days later, although by then it was Saturday afternoon. Watson’s sister Elizabeth, visiting Cambridge en route to Paris and Tokyo, was pressed into service on the pretext that her role was crucial to ‘the most important event in biology since Darwin’s book’. Even with Crick and Watson standing over her, the manuscript did not take long to type, as it was barely 900 words long; it was accompanied by an elegant figure of the double helix, drawn by Odile Crick.

The paper was checked by Bragg the following Tuesday 31 March, and sent off to Nature first thing the next morning, April Fool’s Day. A visiting dignitary from the Rockefeller captured the ‘great air of excitement’ in the Cavendish, with the ‘young and somewhat mad hatters’ and their ‘huge model’, which had come out of ‘the beautiful X-ray diagrams produced in Randall’s lab, and some of the work in Cambridge’.

In early April, two visitors called into Cambridge to inspect the Watson-Crick double helix. The first was Linus Pauling, on his way to a conference in Brussels. There was no sign of his usual cocky showmanship; on arrival in Brussels, he wrote home to his wife and ended his letter reflectively, ‘I think that our structure is probably wrong, and theirs probably right.’ The second visitor was Rosalind Franklin. Watson was surprised to see how ‘gracefully’ she agreed that the double helix must be right. It was as though the dramatic confrontation in King’s which Watson described in such graphic detail had never happened.

Soon after the Watson-Crick paper was dispatched to Nature, Watson ignored Crick’s protestations that they still had work to do and went to Paris with his sister. Elizabeth’s destination was Japan, to marry ‘an American she had known in college’. Brother and sister had always been close, and these were their last few days together in ‘the carefree spirit that had marked our escape from the Middle West’. Watson bought her an expensive umbrella in Faubourg St Honoré, as a wedding present. Just before she flew on, they celebrated Watson’s birthday on 6 April. It was his twenty-fifth, and by his own assessment, he was now ‘too old to be unusual’.

Print run

As is usual for Nature, the issue of 25 April 1953 covered a broad base, including the virus that caused ‘trashy leaf’ in tobacco plants, glucose uptake in the gut, radium on the ocean floor and – of interest to Rosalind Franklin in her previous life – a form of carbon that chewed its way into the brickwork of blast-furnaces. But the undisputed centrepiece that week was a trilogy of papers about the structure of DNA.

The third in the pecking order was by Franklin and Gosling, from the MRC Biophysics Unit at King’s (an asterisk beside Franklin’s name indicated that her present workplace was Birkbeck College). Their article consisted of two pages of heavyweight mathematical analyses of the B form; discussion of the A form was deferred to another paper in press. The B form was illustrated by Photograph 51, which showed ‘in striking manner the features of helical structures first worked out in this laboratory by Stokes’. They were careful to point out that ‘Stokes and Wilkins were the first to propose such structures for nucleic acid fibres, although a helical structure had previously been suggested by Furberg’. The Patterson analyses had led them to conclude that DNA was ‘probably helical’, containing two co-axial chains with the phosphate groups lying outermost and the bases inside. This was ‘not inconsistent with the model proposed by Watson and Crick’. They ended, ‘We are grateful to Professor J.T. Randall for his interest, and to Drs F.H.C. Crick, A.R. Stokes and M.H.F. Wilkins for discussion.’

Wilkins, Stokes and Wilson reached much the same verdict through a different mathematical pathway, the Bessel derivation which Stokes had worked out on the train home and never published. Their theoretical prediction of an X-shaped diffraction pattern was best seen in ‘the exceptional photograph obtained by our colleagues RE Franklin and RG Gosling’, shown in the accompanying paper. The structure of DNA had moved on from Astbury’s pile of pennies, to ‘a spiral staircase with the core removed’, and there appeared to be ‘reasonable agreement with the kind of model described by Watson and Crick’. Crucially, the basic structure of DNA was identical in a wide range of species – mammals, fish, wheat, bacteria and even a bacteriophage virus – and the fact that live spermatozoa showed the same X-ray pattern strongly suggested that this was the form of DNA which occurred in vivo. At the end, Wilkins et al thanked ‘our colleagues, R.E. Franklin and R.G. Gosling; and Dr J.D. Watson and Mr F.H.C. Crick for stimulation’.

And so to the paper which eclipsed the other two; the one that everybody knows about even if they have never read it. Compared with the others, it was short and sweet: a paragon of clarity and conciseness that contains two of the most famous sentences in the scientific literature of the twentieth century. The first was its carefully understated opening, ‘We wish to suggest a structure for DNA. This structure has novel features which are of considerable biological interest.’ Watson and Crick began by demolishing Pauling’s three-stranded model, and also the ‘rather ill-defined’ structure by Bruce Fraser which preceded it. Their own vision was ‘radically different’: two helical chains winding around the same axis, the phosphate-sugar backbones outermost and the bases stacked horizontally up the core. The ‘novel feature’ was ‘the manner in which the two chains are held together by hydrogen bonding between specific pairs of purine and pyrimidine bases’, namely A with T and C with G. This tallied with experimental measurements of bases in DNA, but they did not mention Chargaff by name. The double helix was ‘roughly compatible’ with previously published information and, significantly, with the ‘more exact results’ in the two accompanying papers. Watson and Crick stated that ‘We were not aware of the details of the results presented there when we devised our structure, which rests mainly though not entirely on published experimental data and stereochemical arguments.’

Their double helix was not just neat stereochemically. It was the inviolable pairing of the bases that gave it ‘considerable biological interest’. They acknowledged this with another throw-away line to go down in history: ‘It has not escaped our notice that the specific pairing we have postulated immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material.’

Like the others, Watson and Crick ended with thanks. ‘We have been stimulated by a knowledge of the general nature of the unpublished experimental results and ideas of Dr M.H.F. Wilkins, Dr R.E. Franklin and their co-workers at King’s College, London.’

Their paper was brief because of its economical prose, but mainly because it was not burdened by descriptions of the experiments and analyses that led them to their structure. Most of the necessary data could be found in the papers by Wilkins and Franklin. And the claim by Watson and Crick that ‘we were not aware of the details of the results’ was not challenged by any of those who knew it to be a lie.

Some discoveries just look right from the moment that they are unveiled. The double helix (Figure 24.4) was one of those: beautiful, elegant and with a stroke of pure genius in the way that A paired with T and C with G – so obvious, as soon as it was pointed out, that it had to be the truth.

A few wise men immediately spotted the wider implications. Max Delbrück wrote to Watson: ‘If the suggestion concerning the nature of replication has any validity at all, then all hell will break loose and theoretical biology will enter a most tumultuous phase.’ Linus Pauling thought that ‘their formulation of the structure’ would turn out to be ‘the greatest development in the field of molecular genetics in recent years’. And the entire Biochemistry Department at Oxford descended on Cambridge en masse to pay homage to the model. On their return, they sent a telegram which read simply ‘Congratulations’, from a sender identified as ‘Gene’. Others believed that this should have read, ‘Be careful’, from ‘God’.

Figure 24.4 Schematic drawing of the double helix, showing the deoxyribose-phosphate backbones as ribbons, bridged by the hydrogen bonds (dotted lines) joining the complementary bases, A with T and C with G. The two DNA strands are ‘anti-parallel’, one running ‘up’ and the other ‘down’.

On first seeing the Watson-Crick paper, Sir Lawrence Bragg had confessed that ‘It’s all Greek to me’, but was soon bubbling over with the excitement of the newly converted. In Watson’s words, he quickly ‘got out of control’ and was feeding the story to the lay press as well as the scientific community. This gave Watson an attack of cold feet and what might almost have been a spasm of guilty conscience, because ‘there are still those who think we pirated data and I’m of the belief that a few enemies are worse than a few admirers’. His conclusion was, ‘So the less publicity, the better.’

A few weeks later, Watson was invited to talk about their paper at the Hardy Club in Cambridge. Obtunded by dinner at Peter-house and overlubricated by sherry, he gave what Crick judged to be ‘an adequate description’ of their triumph. At the end, Watson was overcome with emotion and, very unusually, was lost for words. Gazing up at the double helix on the screen, all he could manage was: ‘It’s so beautiful.’

Maurice Wilkins was also there and sat through Watson’s talk, increasingly ‘puzzled’ that there was no reference to any of the work done in Randall’s Biophysics Unit. Afterwards, Watson came to find Wilkins and said he was sorry for having ‘forgotten to mention King’s’.