can you tell us which direction we are taking

caz we waan no whé paat we guen;

bisétuna nasú busini halía badúa lañ;

queremos saber nuestra dirección

whé paat we guen …

If a poem is supposed to consist of exactly the right words and no others, then there are multiple worlds in which poems are never quite finished, never quite closed. In some of these worlds poets use writing, but there is nothing about writing, in and of itself, that requires a text to be fixed for all times and places. Writing, like speaking, is a performance.

If poetics is supposed to belong to the interior of language, as opposed to the exterior realm of referentiality, then there are multiple worlds in which being a verbal artist means pursuing a dual career in poetics and semantics. This does not mean bringing words and their objects into ever closer alignment, but rather playing on the differences. The sounding of different voices does not require putting multiple poets on the same bill, but takes place in the poem at hand. If the poem is written there may be multiple graphic moves in the same text, and these need not be in synchrony with the voices.

If literature means the world of letters, Greco-Roman alphabetic letters, then the poets of these other worlds are not producers of literature. Some of them do use the alphabet, but not necessarily for the purposes intended by lettered invaders and evangelists. For those looking outward from the inside of the Greco-Roman heritage, composing verse with its rhymes blanked, its meter freed, and its breaths notated is not quite enough to open the boundaries between worlds. There is still this recurring desire to close in on exactly the right words. For other poets in other worlds, paraphrase has never been a heresy and translation has never been treasonous.

In geographical terms, alternative poetries completely surround the world of letters and are practiced in the very precincts of its culture capitals. The examples presented here happen to come from speakers and writers of Mayan languages, who number well over six million today. Their homelands lie in Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Belize, and Mexico, and they also have communities in south Florida, Houston, Los Angeles, and the San Francisco Bay Area. The earliest evidence for poetry in their world is a brief text on the back of a jade plaque, written in the Mayan script.1 Included is a date, with the number of the year given as 3483. For those of us who come from within the world of letters that was 320 A.D., before there was any such thing as English literature.

An excellent introduction to Mayan poetics may be found in a sixteenth-century work known as Popol Vuh or “Council Book,” from the highlands of Guatemala.2 It is written in the Mayan language known as Quiché or K’iche’, but in the letters of the Roman alphabet. The authors chose letters in the aftermath of the European invasion, when books written in the Mayan script were subject to being confiscated and burned. They give their lessons in poetics in the course of telling the story of how the gods prepared the world for human beings, and how human beings built towns and kingdoms. Their lessons take the form of examples, but instead of quoting poems by famous authors they offer hypothetical poems of the kinds humans might have performed at different stages in their condition as poets.

From the very beginning the gods wanted to make beings who could speak to them, but their expectations were only partly linguistic. Yes, they did want beings who could put the adjective ch’ipa (newborn) in front of the noun kaqulja (thunderbolt) and say ch’ipa kaqulja, referring to a fulgurite (a glassy stone formed where lightning strikes the ground). And yes, they wanted beings who could combine the stem tz’aq- (make) with the suffix -ol (-er) and say tz’aqol (maker). But their expectations were also poetic. They didn’t yearn to hear complete sentences so much as they wanted to hear phrases or words in parallel pairs, such as ch’ipa kaqulja, raxa kaqulja, “newborn thunderbolt, sudden thunderbolt,” and tz’aqol, b’itol, “maker, modeler.” When they made the beings that became today’s animals and tried to teach them to speak this way, each species made a different sound. Worse yet, a given species simply repeated its cry, as if to say something like tz’aqol, tz’aqol instead of tz’aqol, b’itol. Some animals, especially birds, received their names from their cries. The whippoorwill, which says xpurpuweq, xpurpuweq, is now called purpuweq. The laughing falcon, which says wak ko, wak ko, is called wak.

The whippoorwill can index its own presence with its call, but it can neither name the laughing falcon nor pretend to be one. For Mayans, it is only in this compartmentalized, subhuman domain that wordlike sounds can stay in tidy, isomorphic relationships with their meanings. Once purpuweq and wak become words in a real language, a poet who names the purpuweq may also call it chajal tikon, “guardian of the plants.” Instead of naming the wak straight out, the poet may say jun nima tz’ikin, ri wak ub’i, “a large bird, the laughing falcon by name.” Europeans once imagined a time, lasting from Eden until Babel, when humans spoke a single, original language composed of words that were intrinsically and unambiguously tied to distinct objects. For Mayans this would be a world before language, and certainly a world before poetry.

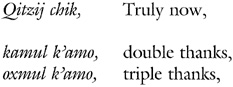

After four tries the gods succeed at making real humans, four of them. When they ask these four to talk about themselves, they get a poem in reply. It opens as shown below, with a monostich followed by a distich whose lines are parallel in both syntax and meaning:

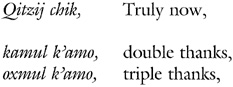

The pairing of words or phrases is by far the commonest gesture in parallel verse, whether it be Mayan or Chinese or else from the ancient Middle East. Equally widespread is the use of a monostich to provide a frame, as in this example, or to mark internal transitions.3 The gods would have been perfectly happy with a composition that followed the first distich with a succession of other distichs of similar construction, but they had unwittingly created poets who were more than versifiers. Even the distich has a twist to it, playing off form against meaning by pairing “double” with “triple.” The poem continues with a tristich that has a playful turbulence in its syntax, with each line structured slightly differently from the others. Then comes a tetrastich, the rarest of the forms employed so far, but its unusual length is compensated by the uniformity of its syntax:

In verse of this kind groups of parallel lines can be isometrical, as in the case of the four-syllable lines that make up the distich, but they can just as well be heterometrical, as in the case of the lines of six, five, and four syllables that make up the tristich. In the passage as a whole, lines range from three syllables (in the monostich and the first line of the tetrastich) to twice that number (in the first line of the tristich). There are rhythms here, but they are temporary rhythms created by temporary alignments of syntax and therefore of meaning. There are rhymes as well, in the broad sense of recurring combinations of consonants and vowels, but again they are aligned with syntax and meaning. The effect is to foreground the parts of parallel lines that do not rhyme, which is to say, the morphemes or words that change from one line to the next without changing their position within the line. In the distich, everything rhymes except for the morphemes ka- and ox-, equivalent to “dou-” and “tri-” in the translation. In the tetrastich, the repetition of the morphemes k- (incomplete aspect), -oj- (first-person plural), and -ik (clause-final verb ending) places the emphasis on the contrasting verb stems they enclose.

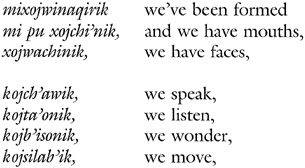

The first sentence uttered by the first human beings is not yet over, and as it continues they add a few more poetic moves to the ones they’ve tried already. In syntactic terms their next line is a monostich, contrasting in structure with the lines that immediately precede and follow it, but in semantic terms it forms a tristich with the syntactic distich that follows it, creating a momentary tension between form and meaning:

The first of the two distichs harbors a slight syntactic change of its own, adding mi (perfect aspect) and pu (a conjunction) in front of the verb in the second line, and each of its lines harbors a smaller-scale distich, composed of naj nakaj (far near) in one and nim ch’utin (great small) in the other. The latter line is the longest in the whole sentence, running to seven syllables, but the first line of the final distich drops all the way back to three, returning to the shortness of the monostich that began the sentence.

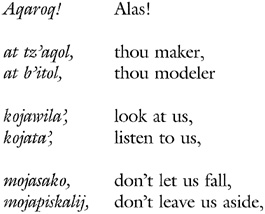

Each of the poetic moves in this first of all human sentences can be found elsewhere in Quiche and other Mayan poetry, whether ancient or contemporary, but seldom are so many different moves employed in so short a time. This is the performance of beings who have, for the moment, complete understanding of everything in the world, and the utterance itself is a poetic tour de force. The gods are alarmed by what they have wrought and decide to cloud the vision of the first humans. After that “it was only from close up that they could see what was there with any clarity,” and with this came a decline in their poetic abilities. Reduced to mortals who could only communicate with the gods from a distance, they began their first prayer as follows:

After the opening monostich, consisting of a lament called out to unseen gods in the distance, comes an unbroken series of distichs that rolls on for many more lines beyond the ones quoted here. The first distich is isometrical, but the rest at least have the virtue of having unequal hemistichs.

After a long period of wandering in darkness, humans recover some of their lost understanding. They become dreamers and diviners, and they also learn how to use ilob’al, “instruments for seeing,” such as crystals and books. At the same time they regain their former poetic skills, but unlike the first poets they don’t squander all their best moves in just a few lines.

One of the effects of parallel verse is what the Sinologist James Hightower called “verbal polyphony.”4 This effect is prominent in Russian folk poetry, but M. M. Bakhtin left that out of consideration when he set up an antithesis between poetry, which he declared to be monological, and the dialogical or polyphonic discourse of the novel. Tracing dialogical effects all the way down to the scale of individual words, he noted that a given word exists in an environment of other words that could have been used with reference to the same object, and that these other words may come to the mind of the hearer or reader.5 What happens in parallel verse is that one or more of these other words is actually given voice. Consider this distich from the opening of the Popol Vuh:

Waral xchqatz’b’a wi

xchiqatikib’a wi Ojer Tzij.

Here we shall inscribe

we shall implant the Ancient Word.

By using the stem tz’ib’- in the first line, the authors refer to writing without venturing into figurative usage. But then, in the second line, they use the stem tiki-, which refers to planting—not in the sense of sowing seeds that will become something else, but in the sense of planting (or transplanting) something that is already a plant in its own right. That something is the Ancient Word, which the authors are transplanting from one book, written in the words and syllables of the Mayan script, into another book, written in the consonants and vowels of the Roman script. In both cases the signs in the graphic field are planted in rows.

The completion of a group of parallel lines that share a common object does not imply that all has been said that could be said about it. In other passages about writing, the authors of the Popol Vuh use other words they could have used here. For example, they might have added a phrase that included the word retal, “sign, mark, trace,” which refers to a clue left behind by a past act, such as a footprint. Or they might have made use of wuj, literally “paper” but a metonym for “book.” If they had been inscribing a wood or stone surface instead of paper, they might have invoked k’ot (carving), a stem they later pair with tz’ib’ (writing) when referring to the scribal profession.

It could be argued that the choice the authors actually made in the passage quoted above, to pair planting with writing, ultimately clarifies what they are proposing to do. But the notion of planting serves this purpose only by way of a figurative detour that leaves a residue of additional meanings that would only complicate matters if we stopped to explore them. If we want parallel lines to bring their common object into focus with a minimum of complication, a better example is provided by passages in which the authors pair the word poy, which refers to dolls or manikins but doesn’t tell us what they are made of, with ajamche’, which refers to woodcarvings but doesn’t tell us, by itself, that the woodcarvings in question are manikins. The Sinologist Peter Boodberg compared the effect of this kind of distich to stereoscopic vision,6 a notion that has been picked up by various students of parallelism. But I think Jean-Jacques Rousseau came closer to the mark when he wrote, “The successive impressions of discourse, which strike a redoubled blow, produce a different feeling from that of the continuous presence of the same object, which can be taken in at a single glance.”7 It needs to be added that there is no moment at which the successive blows of discourse hammer out a complete object, but only a moment in the course of a performance at which writers or speakers either stop or move on to something else.

In some passages the writers of the Popol Vuh leave their “manikins, woodcarvings” behind right away, but in others they add such statements as xewinaq wachinik, xewinaq tzijonik puch, “They were human in looks, they were human in speech as well.” It might be claimed that this distich clarifies the picture further, even beyond what the addition of “woodcarvings” did for “manikins,” but it also has the potential for contradicting an image we had already formed and replacing it with a new (and still incomplete) image, or making us wonder whether someone is ventriloquizing the manikins, which now sound like puppets, and so on. Instead of being present continuously, the object never quite becomes identical with itself.

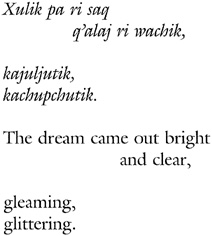

There are times when parallel words or phrases, instead of constructing an object out of its parts or aspects, converge on saying nearly the same thing about it. The example given below also happens to shed light on how contemporary speakers of Quiché construct the relationship between language and experience. It comes from a conversation in which Barbara Tedlock and myself were learning how to talk about dreams from Andrés Xiloj Peruch, a diviner. When we asked whether one could describe a q’alaj wachik (clear dream) as kajuljutik (shining or gleaming), he began with a charitable “yes” but then suggested a more acceptable statement:

Thus he produced the word saq, “light, white, bright,” to make a pair with a word from our question, q’alaj, which refers to clarity (as opposed to obscurity) and can be used to describe discourse. Then he took the onomatopoeic verb kajuljutik, whose reduplicated stem (julju-) gives it the character of a small-scale distich, and added a second verb with a reduplicated stem (chupchu-). Both verbs indicate some degree of fluctuation in the reception of this “bright and clear” dream, but with a slight difference. Julju- carries a sense of acuteness that includes the prickliness of spines and the piquancy of chili, while chupchu- is less fine-grained, evoking sensations that include the flickering of a candle and the splashing of water. The effect of the sentence as a whole is to raise the discontinuity of the “presence of the same object” to a high frequency. To paraphrase (and subvert) Charles Olson’s version of the famous dictum of Edward Dahlberg, one perception immediately and directly leads to a separate perception of the same object.8

The convergence of meaning in Xiloj’s statement is supported not only by vocabulary and syntax, but also by the assonance and alliteration that link saq with q’alaj and kajuljutik with kachupchutik. But there are other moments in which resonances of this kind are used to rhyme words that are parallel neither in syntax nor in meaning. The purpose is not to answer the demands of a rhyme scheme, but to make a pun. The Quiche term for punning is sakb’al tzij, “word dice.” Winning combinations of words that share sounds create a sudden shift in meaning that is nevertheless appropriate to the matter at hand. Hearing such a shift provokes neither groans nor outright laughter, but a chuckle or “ah” or “hm” of recognition. Diviners often interpret the Quiche calendar by speaking the number and name of a given date and then giving its augury by playing on the name.9 Here are three successive dates, each accompanied by two alternative auguries:

There are times when phrases that are properly parallel in their syntax and meaning nevertheless stand at a considerable distance from one another, opening up a whole range of distinct objects between them. The following example, from the Popol Vuh, evokes the powers of shamans:

Xa kinawal,

Xa kipus xbd’anataj wi.

Their genius alone

their sharpness alone got it done.

To possess nawal is to possess genius in the old sense of the word, adding the powers of a spirit familiar to one’s own. A second power is pus, literally referring to the cutting open of sacrificial flesh but here understood as the ability to reveal, with a single stroke, something deeply hidden. As a pair these words imply a range of shamanic powers, not because they comprise two grand categories into which everything else fits but because they form a pair of complementary metonyms. The authors could have made a further power explicit by adding (for example) xa kitzij, “their words alone,” but instead they chose to use this phrase elsewhere.

In Mayan languages, as in Chinese, complementary metonyms may be compressed into a single word. Here are some Quiche examples, hyphenated to show the locations of suppressed word boundaries; each is followed by a literal English rendering and an explanation:

Even when Mayans make long lists instead of stating a double metonymy, they seem to let some items that could be on the list remain implicit, as if resisting totalization. The authors of the Popol Vuh stop at either nine or thirteen generations when they list the predecessors of the current holders of noble titles, not because the historical total for any lineage was nine or thirteen, but because these numbers belong to a poetics of quantity, one that continues to be followed in present-day invocations of ancestors.10 The names not mentioned in the Popol Vuh, though perhaps not all of them, can be found by consulting other sixteenth-century sources. There are several documents containing overlapping lists, no two of which are identical in their choices.

Proper names would seem to have at least the potential for bringing words and objects into stable, isomorphic relationships, but they are not exempt from the poetics of saying things in more than one way. Mayan speakers and writers are fond of undoing the “proper name effect,” which, to quote Peggy Kamuf’s translation of Claude Lévesque’s quotation of Jacques Derrida, is manifested by “any signified whose signifier cannot vary nor let itself be translated into another signifier without loss of meaning,” which is to say without the loss of one-on-one referentiality.11 When the authors of the Popol Vuh invoke a proper name that might seem foreign or otherwise opaque to their readers, they often gloss it instead of allowing it to remain in isolation. In telling an animal tale they introduce one of the characters by writing, Tamasul u b’i, ri xpeq, or “Tamazul is his name, the toad.” Thus they treat their version of tamazulin, the ordinary Nahuatl (Aztec) term for a toad, as a proper name, but then demystify this name by supplying xpeq, the ordinary Quiché term for the same animal. In the course of telling how the name of the god Hacauitz came to be given to a mountain, they produce the following pair of phrases:

Mana pa k’echelaj xk’oje wi Jakawitz,

xa saqi juyub’ xewax wi Jakawitz.

Hacauitz didn’t stay in the forest,

Hacauitz was hidden instead on a bald mountain.

Here they show their knowledge of Chol, a Mayan language in which jaka witz is literally “stripped mountain,” a condition described by saqi juyub’, “bare (or plain) mountain,” in Quiché. The effect they create is something like that of disturbing the properness of the name Chicago, which comes from an Algonkian language, by remarking, “Chicago was founded in a place where wild garlic once grew.”

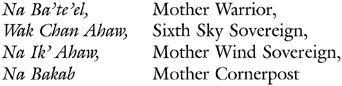

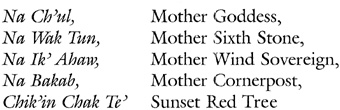

Another way Mayans dispel the properness of names is to multiply them. This is not simply a matter of using both a name and a surname (Robert and Creeley), but it does resemble the cases of a name and nickname (Robert and Bob) or a name and an epithet (Buffalo and Nickel City). What remains different is that a single proper name, unless it forms part of a list of persons or places that parallel one another, is likely to be denied self-sufficiency. Instead of replacing some other name, a nickname or epithet is invoked alongside it, as if to say “Robert Bob” or “Buffalo Nickel City.” An eighth-century picture of a Mayan noblewoman at the site of Yaxchilán, in Chiapas, is captioned as follows:12

The use of the Mother and/or Sovereign titles with each of the four names equalizes them, making it impossible to tell the difference between primary names and secondary epithets (if indeed there is any). The caption for another picture of the same woman utilizes some of the same words and adds others:

For the original writers and readers of these captions, the multiple names may have evoked discontinuous aspects of this woman’s history, personality, or powers. In other words, the effect would have been different from that of the continuous presence of the “same” person.

Whether parallel words or phrases refer to the same (although intermittently present) object, or else point to objects other than the particular ones they name, they constantly work against the notion that an isomorphism between words and their objects could actually be realized. To paraphrase (and invert) Charles Olson’s version of the famous dictum of Robert Creeley, this is a poetics in which form is always other than an extension of content.13

A parallel poetics stands opposed to the philosophical or scientific project of developing an object language whose meanings have been shorn of all synonymy and polysemy. At the same time it stands opposed to the literary project of protecting poems against the “heresy of paraphrase” by treating them as if they were Scripture, composed of precisely the right words and no others. To paraphrase (and invert) Charles Bernstein’s rephrasing of the orthodox position of I. A. Richards and/or Cleanth Brooks, a parallel poetics is one in which a poem not said in any other way is not a poem in the first place.14

In a poetics that always stands ready, once something has been said, to find other ways to say it, there can be no fetishization of verbatim quotation, which lies at the very heart of the Western commodification of words. In the Mayan case not even writing, whether in the Mayan script or the Roman alphabet, carries with it a need for exact quotation. When Mayan authors cite previous texts, and even when they cite earlier passages in the same text, they unfailingly construct paraphrases. Such is the case at the site of Palenque, in Chiapas, where three eighth-century temples contain texts that tell a long story whose episodes are partly different and partly overlapped from one temple to the next. Among the events are the formation of the present world by the gods and the deeds of kings who claim divine inspiration, but the text is not what we would call Scripture. In the overlapping episodes not a single sentence is repeated verbatim from one temple to another. Smaller-scale examples of paraphrase occur in the dialogues among characters in the Popol Vuh. When spoken messages are sent through third parties, the words that are quoted as having been sent and those that are quoted as having been delivered never match one another verbatim. This is true even in an episode in which the senders are described as having messengers who “repeated their words, in just the same order.” Here are before and after versions of a sentence from the message:

Chikik’am k’u uloq ri kichoqonisan.

So they must bring along their sports gear.

Chik’am uloq ri ronojel ketz’ab’al.

He must bring along all their gaming equipment.

It would have been easy for the authors to match the quotations letter for letter, since they occur on the same page, but they didn’t bother. The two sentences are at least parallel, or put together “in the same order,” and they share a focus on sports equipment.

Our own notions of accurate quotation have been shaped, in part, by print technology, which finds its purest expression in the exact reproduction of Scripture and other canonized texts. The technology of sound recording is a further chapter in the same grand story of representation, but it produces a surplus of aural information that causes problems for text-based researchers who turn their attention to recorded speech. Folklorists have a way of making “oral formulaic composition” sound like a primitive predecessor of typesetting, providing a partial remedy for the crisis of memory that supposedly afflicts the members of oral cultures. Linguists have a way of making “performance” sound as though it were an optional addition to a standard software package, one that would otherwise print out a perfectly normal text. Meanwhile, in the poetics of parallelism, variation is not something that waits for a later performance of the same poem, but is required for the production of this poem, or any poem, in the first place.

Translation caused anxiety long before the current critique of representations, especially the translation of poetry. Roman Jakobson pointed the way to a new construction of this problem, suggesting that the process of rewording might be called intralingual translation.15 Here we may add that within parallel verse, not only in theory but in practice, the further step to interlingual translation may take place, with words from two different languages dividing an object between them. In the simplest case the passage from one parallel phrase to the next entails the replacement of a single word with its near-equivalent in another language.

The epigram to this essay changes languages by whole phrases, passing from standard English to Belizean Creole to Garífuna (an Amerindian language spoken by Belizean blacks whose ancestors learned it on St. Vincent) to Spanish and then back to Creole, ironically bypassing the indigenous language of Belize (Mopán Maya).16 In the macaronic verse of medieval Europe, the changes took place between Latin and the local vernacular. Quiché writers of the sixteenth century sometimes paired words from Nahuatl (the language of the Aztecs) with Quiché equivalents. In the Popol Vuh two terms for a royal house or lineage, chinamit (from Nahuatl chinamitl) and nimja (Quiché), are paired in e oxib’ chinamit, oxib’ puch nimja, which might be translated as “those of the three casas grandes and three great houses.” In contemporary discourse Spanish has taken the place of Nahuatl, as in this double question from a story told by Vicente de León Abac of Momostenango: Jasa ri kab’anoq chech? De que consiste? This is something like saying, “What could be happening to them? Was ist das?”

Here we have entered a realm in which the popular notion of an enmity between poetry and translation does not apply. To quote Robert Frost’s famous phrasing of this notion, as remembered by Edwin Honig in conversation with Octavio Paz, “Poetry is what gets lost in translation.”17 As Andrew Schelling remembers this exchange, Paz countered Honig by paraphrasing Frost, saying, “Poetry is what is translated.” To take this statement a step further and paraphrase it for purposes of the present discussion, poetry is translation.

Frost’s notion is an ethnocentric one, rooted in a poetic tradition that has devoted much of its energy to manipulating linguistic sounds at a level below that of words and syntax, which is to say below the level of segments that have already begun to carry meaning. This is the level that is most resistant to translation—unless we do as Louis Zukofsky did, finding English meanings to fit the sounds of Catullus. But in a tradition that does its main work above the phonetic level, translation is one of the principal means by which poems are constructed in the first place. Translation into a further language at a later date, like nonverbatim quotation at a later date, then becomes a continuation of a process already under way in the poem itself.

Keeping parallel phrases parallel solves one kind of translation problem but raises others, among them the question of graphic representation. To speak of “parallel lines” is to speak the language of alphabetic writing even before the letters are arranged in lines on a page. For well over a thousand years, Mayan poetry was written in a graphic code that looks quite different from the one in which the texts quoted so far have been cast. In his Mayan Letters, Olson first suggested that “the glyphs were the alphabet of [Mayan] books,” which “puts the whole thing back into the spoken language.” Four days later he wrote, “A Maya glyph is more pertinent to our purposes than anything else,” because “these people … had forms which unfolded directly from content.”18 Taken together, these statements project the dream of a writing system that is transparent to language and the world at one and the same time. As it turns out the signs of Mayan writing do notate linguistic sounds, but they do not constitute an alphabet. And, though some signs do take their forms from objects in the world, they rarely mean what they look like.

Instead of notating consonants and vowels, Mayan signs go by syllables and whole words. And where an alphabet constitutes a closed code, fixed at a small number of signs that are (ideally) isomorphic with the sounds they notate, Mayan signs (like Egyptian and Chinese signs) are abundant, providing multiple ways of spelling any given syllable or word. This kind of script is reader-friendly in its own particular ways, permitting the annotation of a word sign with a syllabic hint as to its pronunciation, or permitting a reader to recall a forgotten sign or learn a new one by comparing two different spellings in places where the text would seem to demand the same word. It is also writer-friendly, presenting choices that are more than a matter of calligraphy or typography. Here we need a new term or two, perhaps polygraphy or diagraphism. Just as a Mayan poem reminds the hearer that different words can be used with reference to the same object, so a Mayan text reminds the reader that different signs can be used for the same syllables or words.

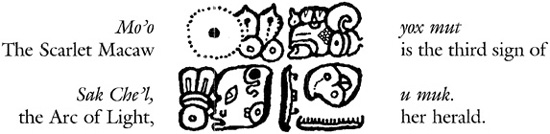

When a Mayan sign appears to be iconic, its object, if we want to get on with the reading of the text, is usually a sound rather than the thing it

pictures. In this pair of signs  written by a poet/scribe of the fifteenth century, the upper one is the profiled head of a mut, a kind of partridge. But here it is meant to be read as the syllable mu, and below it is a sign for ka, read as the sound of k alone in this position, where it completes the word muk, “herald” or “augur.” Now it happens that the bird called mut is an augur, a giver of signs or omens, and that its name serves as a metonym for omens in general, which may be why the poet chose this particular way of spelling muk. It also happens that the same poet used the word mut in the other half of the same distich in which muk appears, but

written by a poet/scribe of the fifteenth century, the upper one is the profiled head of a mut, a kind of partridge. But here it is meant to be read as the syllable mu, and below it is a sign for ka, read as the sound of k alone in this position, where it completes the word muk, “herald” or “augur.” Now it happens that the bird called mut is an augur, a giver of signs or omens, and that its name serves as a metonym for omens in general, which may be why the poet chose this particular way of spelling muk. It also happens that the same poet used the word mut in the other half of the same distich in which muk appears, but

chose to spell it with this pair of signs:  The upper element stands for mu and the lower one for ti, here read as the t sound that completes the word mut. As in the case of two lines of verse that are parallel semantically but not syntactically, the result is a tension between form and meaning.

The upper element stands for mu and the lower one for ti, here read as the t sound that completes the word mut. As in the case of two lines of verse that are parallel semantically but not syntactically, the result is a tension between form and meaning.

These examples of Mayan spelling have been extracted from larger characters or glyphs, which often include more than two signs apiece. The signs that make up a glyph are clustered in a rectangular space and account for at least one complete word. The glyphs themselves are arranged in double columns, with each pair of glyphs read from left to right and each pair of columns read from top to bottom. With such a format it would have been easy for Mayan poets to create graphic displays of the structure of parallel verse, bringing variable syllable counts into line by packing more signs into some glyphs than others. In books the minimal text consists of four glyphs, one pair beneath the other. Even the quarter-inch glyphs used in books sometimes contain as many as six syllables, so four glyphs could have been composed in such a way as to spell out two full distichs, one beneath the other. A more legible text could have been produced by giving each half of a distich a whole line (two glyphs) to itself. What the scribes did instead, more often than not, was to devote most of the available space to the first part of a distich and then resort to ellipsis for the second part. The following text (the source of the signs discussed above) is from an almanac that tracks the changing relationship between the moon goddess and the fixed stars. It concerns moon rises preceded by the appearance of the Macaw constellation (the Big Dipper):19

A priest-shaman reading aloud from this text in the presence of a client would have had the option of expanding upon “her herald” to fill out the second hemistich, saying some or all of “[the Scarlet Macaw] is the [third] herald of [the Arc of Light].” A further option might have been the substitution of alternative names, such as Wuk Ek’ (Seven Stars) for “Scarlet Macaw,” or Pal Ú (Young Moon) for “Arc of Light.”

In longer texts Mayan scribes created a sustained counterpoint between poetic structure and visual organization. At the scale of a whole composition they sometimes divided a text covering two major topics into two blocks of writing with an equal number of glyphs, but always with the transition between the two topics offset from the visual boundary in the text. The boundary was as likely to fall in the middle of a sentence as anywhere else, as in the case of the excerpt below.20 It opens the second half of a text that is divided into right and left halves by a picture. The first pair of phrases, “on 2 Kib 14 Mol” (a two-part date on the Mayan calendar), corresponds to two glyphs written side by side, but a similar pair appearing later, “3 Kaban 15 Mol,” is split between two lines. The distich “Sun-Eye Sky Jaguar, Holy Lord of Egrets” is written with paired glyphs the first time it appears, but the same two glyphs are split between lines the second time. The double name of the temple where the inscription is located, “Thunderbolt Sun-Eye” and “Feathered Jaguar,” is carried by paired glyphs (with “temple” appended to the second), but the two glyphs that give the double name of a portion of the Milky Way, “Hollow Tree” and “Sky Granary,” are divided between lines. Moreover, “Hollow Tree” is in the right half of a glyph whose left half, “It happened at,” starts a new sentence in the middle of a line. The tristichs in this passage—“Mirror, Thunderbolt, Sustainer of Dreams” and “Sixth Sky Thunderbolt, three Jaguar Thunderbolts, Holy Lady of Egrets”—could have been squared up by spelling out their Mayan equivalents with even numbers of glyphs, but in both cases the scribe chose to highlight their oddness rather than conceal it, using exactly three glyphs.

Though the pairing of glyphs in ancient Mayan texts cross-cuts the structures of Mayan verse, it still keeps verse in visual play at least part of the time. In this respect it stands between the graphic practices of ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt, where a text in verse looks the same as any other, and those of ancient Greece and Rome, where verse was written in lines that mirrored its structure. In the beginning, Greco-Roman lines were those of isometric verse, and the lines of various European poetries have followed suit for most of their history. In purely graphic terms, such verse has a curious kinship with prose. When Greeks and Romans wrote prose, they strove for a justified right margin and broke words wherever necessary. When they wrote verse they left the right margin just ragged enough to call attention to the achievement of a near-match between the organization of discourse and the organization of the graphic field. The addition of end rhymes made this achievement still more visible. Against this background the contemporary move to verse that is not only blank (note the visual metaphor) but also free of isometric schemes created a deficit in the visual display of poetic artifice. Olson, as if seeking to compensate for this, wanted the poet to use typography “to indicate exactly the breath, the pauses, the suspensions even of syllables, the juxtapositions of parts of phrases, which he intends.” 21 His project comes very close to reversing a long-standing Western subordination of voice and ear to the scanning eye, but he reaches for the voice without letting go of the notion that the poem said in some other way is not the poem. To get the poet’s intentions right, he tells us, we must repeat not only the words but the breaths, pauses, and suspensions as well.

As we have seen, Mayan poets who used the Mayan script chose to treat the graphic field and parallel verse as semi-independent systems rather than forcing one to mirror the other. When they adopted the Roman alphabet they chose to put everything they wrote (except for a few lists) into a prose format with occasional paragraph breaks. Some of our own poets—Gertrude Stein and Lyn Hejinian, for example—have also chosen to use a

From the tablet in the Temple of the Foliated Cross at Palenque in Chiapas, Mexico. The reading order is left to right and top to bottom. The date 2 Kib 14 Mol fell on 18 July 690, when Sun-Eye Sky Jaguar was Holy Lord of Egrets (the king who ruled from Palenque). The Divine Triplets or three Jaguar Thunderbolts (Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn) had all met up with Sixth Sky Thunderbolt (Antares) at the foot of Hollow Tree or Sky Granary (the part of the Milky Way that currently stood on the southwest horizon at midnight). On 3 Kaban is Mol (19 July) the triplets were joined by their mother, Lady Sky or Holy Lady of Egrets (the moon). Sun-Eye Sky Jaguar then called up the ghost of her namesake, a former queen of Palenque and his own grandmother.

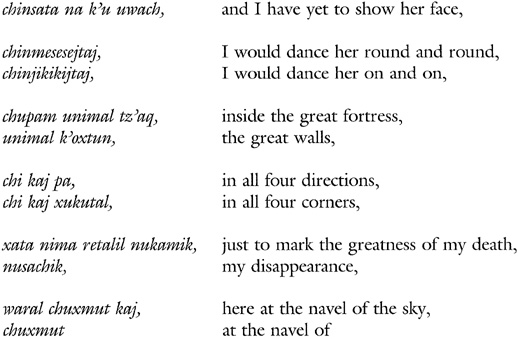

prose format for parallel phrasing. The five lines of Quiché prose illustrated below come from the manuscript of an ancient play known as Rab’inal Achi, “Man of Rabinal,” or Xajoj Tun, “Dance of the Trumpet”:22

Demonstrating the verse in such texts for the European eye requires reorganizing them into parallel lines, as I have done for the Popol Vuh excerpts already presented. Scanning the present text (and modernizing its sixteenth-century orthography) yields the following results:

As they were written on a page, these lines happen to begin halfway through a distich (the first half translates as “I have yet to show her mouth”) and end in the midst of a hemistich (which ends with “the earth”). The scanned version appears to rescue the poetry from the prose, but there remains the problem of how to voice it. Taking our own verse tradition as a guide, we might end each hemistich by lowering our pitch (as indicated by the commas) and then pausing. Or we could modify this approach by saving our pauses for the transition between one full distich and the next, which would put our combination of pitches and pauses directly in the service of the hierarchical structure created by the scanning eye. But that is not the way these words are performed by an actor.

Just as the phrasing of Mayan glyphs interacts with the structure of verse without being reduced to a mere instrument of scansion, so does the phrasing created by Mayan pitches and pauses. Pitch contours and pauses also interact with one another, but without being mere functions of one another.23 The punctuation and line breaks in Emily Dickinson’s manuscripts make it plain that she understood the polysystemic nature of spoken phrasing quite well, and the simplifications carried out by the editors of older printed versions testify to the dominance of eye over ear in mainstream Western poetics. In the case of the Mayan play, the art of speaking the parts has been passed along orally, in company with the manuscript. José León Coloch, the present director and producer of the play, coaches the actors by reading their parts aloud. When he speaks the passage under discussion here it comes out as shown below. Each dash indicates a slight rise, each new flush-left line is preceded by an unmistakably deliberate pause, and the final period indicates a sentence-ending drop in intonation:

and I have yet to show her face—

I would dance her round and round—

I would dance her on and on—

inside the great fortress—

the great walls—

in all four directions—

in all four corners—

just to mark the greatness of—

my death—my disappearance—here at the navel of the sky—at the navel

of the earth.

Thus hemistich boundaries are marked in the same way as distich boundaries. The tension created by the pauses at these boundaries, instead of being softened by a slight fall in pitch that would signal the completion of a phrase or clause (but not a sentence) in ordinary conversation, is heightened by a slight rise that emphasizes incompleteness. A slightly steeper rise would imply a question, signaling that the hearer should complete the pitch contour by providing an answer with a terminal drop (as we do in English). In other words, each successive line is poised on the edge of a question-and-answer dialogue, but the second half of a distich is not allowed to sound like an answer to the question raised by the first half. These quasi-questions go on piling up until the tension reaches its high point with the line “just to mark the greatness of—,” where syntactical incompleteness (or enjambment) reaches its high point and the completion of a hemistich is withheld until the next line. The phrases in that line continue to be marked off by rises, but the elimination of pauses lessens the suspense and a sentence-terminal fall (marked by a period) releases it. At the largest scale, this passage might be said to raise a list of questions for which the long last line provides an answer.

Like the director of the Rabinal play, Quiché poets who specialize in the performance of prayers treat verse phrasing, intonational phrasing, and pause phrasing as three semi-independent systems. In this excerpt from the opening of a prayer spoken by Esteban Ajxup of Momostenango, the commas indicate slight drops in pitch, in contrast to the slight rise indicated (as above) by a dash:

Sacha la numak komon nan—

komon waq remaj,

komon waq tik’aj,

komon chuch, komon qajaw,

komon ajchak, komon ajpatan, komon ajbara, komon ajpunto, komon ajtz’ite,

komon ajwaraje,

uk’amik, uchokik, wa chak, wa patan, chikiwa ri nan, chikiwa ri tat,

Pardon my trespass all mothers—

all six generations,

all six jarsfull,

all matriarchs, all patriarchs,

all workers, all servers, all mixers, all pointers, all counters of seeds, all

readers of cards,

who received, who entered, this work, this service, before the mothers,

before the fathers,

Here the opening monostich has been created by means of ellipsis; it could have been followed by some or all of “pardon my trespass all fathers.” Next comes a distich whose delivery as two separate lines, each of them ended with a slight drop in pitch, marks if off from what comes before and after. The next distich is run on as a single line, which again sets it off (but in a different way). There follows a further acceleration, with two very long lines in succession. They are parallel in the sense that each consists of three distichs, and in the sense that they are identical in their pitch and pause phrasing, but there is a tension between them at the level of syntax. The first one reiterates a single grammatical pattern six times, while the second moves through three different patterns, repeating each one twice. As in the case of performances of the Rabinal play, there is no moment in Ajxup’s performances at which a sustained pattern of pitches and pauses falls into lock step with scansion.

Following Bakhtin, we could try to see the complexity of Mayan poetry as the result of a conflict between centripital forces in language, which are supposed to produce formal and authoritative discourse, and centrifugal forces, which are supposed to open language to its changing contexts and foment new kinds of discourse.24 But this is a profoundly Western way of stating the problem. Available to speakers of any language are multiple systems for phrasing utterances, including syntax, semantics, intonation, and pausing. Available to writers (even within the limits of a keyboard) is a variety of signs, of which some are highly conventional and particulate while others are iconic and may stand for whole words. There is nothing intrinsic to any one of these various spoken and written codes, not even the alphabet itself, that demands the reduction of all or any of the others to its own terms. Bringing multiple codes into agreement with one another is not a matter of poetics as such, but of centralized authority. It is no accident that Mayans, who never formed a conquest state and have kept their distance from European versions of the state right down to the current morning news, do not bend their poetic energies to making systems stack.

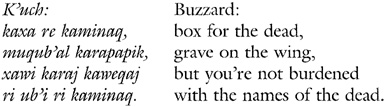

Lastly, a poem written by Humberto Ak’abal of Momostenango.25 By means of an animal metaphor he evokes the recent Guatemalan civil war, with its helicopter gun ships and clandestine cemeteries. But instead of extending his chosen metaphor into a systematic allegory, he runs it up against the fact that animals are without language, thus evoking the story told in the Popol Vuh:

1. For a detailed account of this artifact, which is known as the Leyden Plaque after its present location in the Netherlands, see Floyd G. Lounsbury, “The Ancient Writing of Middle America,” in The Origins of Writing, ed. Wayne M. Senner (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1989), pp. 205–8.

2. This and other textual excerpts from the Popol Vuh or Popol Wuj are given in the official orthography of the Academia de las Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala and include emendations of the manuscript. For a complete translation see Dennis Tedlock, Popol Vuh: The Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life, rev. ed. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996).

3. See Roman Jakobson, Language in Literature, ed. Krystyna Pomorska and Stephen Rudy (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1987), p. 156.

4. Cited in a 1959 source not available to me by Roman Jakobson, in Jakobson, 172. He relies heavily on Hightower when discussing parallelism in Russian poetry.

5. M. M. Bakhtin, The Dialogic Imagination, tr. C. Emerson and M. Holquist (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981), pp. 68–82.

6. Peter Boodberg, “Cedules from a Berkeley Workshop in Asiatic Philology,” in Selected Works of Peter A. Boodberg, comp. Alvin P. Cohen (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979), p. 184.

7. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “Essay on the Origin of Languages,” in On the Origin of Language, tr. by John H. Moran (New York: Frederick Ungar, 1966), p. 8.

8. See Charles Olson, Selected Writings, ed. Robert Creeley (New York: New Directions, 1966), p. 17. Olson’s version of Dahlberg’s statement, which Olson means to keep the poet moving fast rather than lingering, is “ONE PERCEPTION MUST IMMEDIATELY AND DIRECTLY LEAD TO A FURTHER PERCEPTION.”

9. For more on this see Barbara Tedlock, Time and the Highland Maya, rev. ed. (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1992), chap. 5.

10. Dennis Tedlock, 56, 194–97.

11. Claude Levesque, Introduction to “Roundtable on Translation,” in The Ear of the Other: Otobiography, Transference, Translation, ed. by Christie V. McDonald (New York: Schocken, 1985), p. 93.

12. The two pictures and captions discussed here are on lintels 41 and 38, illustrated and glossed in Carolyn E. Tate, Yaxchilan: The Design of a Maya Ceremonial City (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1992), pp. 177–78, 250–51, 277–78. The translations are mine.

13. Olson, 16. His version of Creeley’s statement is “FORM IS NEVER MORE THAN AN EXTENSION OF CONTENT.”

14. Bernstein’s formulation, “The problem is that the poem said in any other way is not the poem,” may be found in his A Poetics (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1992), p. 16.

15. Jakobson, 429.

16. The epigram is from the end of a longer poem in Luke E. Ramirez, The Poems I Write (Belize: Belizean Heritage Foundation, 1990), p. 17. The ellipsis is in the original.

17. Edwin Honig, The Poet’s Other Voice: Conversations on Literary Translation, ed. Edwin Honig (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1985), p. 154.

18. Olson, 108, 113.

19. The hieroglyphic text, in Yucatec Maya, is from p. 16c of the Dresden Codex, which is reproduced in full in J. Eric S. Thompson, A Commentary on the Dresden Codex (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1972). The alphabetic transcription is a revised version of the one given in Charles A. Hofling, “The Morphosyntactic Basis of Discourse Structure in Glyphic Text in the Dresden Codex,” in Word and Image in Maya Culture: Explorations in Language, Writing, and Representation, ed. William F. Hanks and Don S. Rice (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1989), p. 61. The translation is mine.

20. For a detailed discussion of this text, see Linda Schele, XVI Maya Hieroglyphic Workshop at Texas (Austin: Department of Art and Art History, University of Texas, 1992), pp. 169–74. My departures from her views are minor at the level of the phonetic values she assigns to the glyphs but considerable at the level of translation and interpretation. In separating the incomplete and complete aspects of verbs (rendered here as present and past tenses) I follow Stephen D. Houston, “The Shifting Now: Aspect, Deixis, and Narrative in Classic Maya Texts,” American Anthropologist, vol. 98, pp. 291-305 (1997).

21. Olson, 22.

22. From Miguel Pérez, “Rabinal achi vepu xahoh tun,” p. 57. Manuscript dated 1913, copy in the Latin American Library, Tulane University. This is the most recent in a series of copies made over a period of centuries in the town of Rabinal.

23. For a linguistic discussion of the contrasts among different kinds of phrasing, see Anthony C. Woodbury, “Rhetorical Structure in a Central Alaskan Yupik Eskimo Traditional Narrative,” in Native American Discourse: Poetics and Rhetoric, ed. Joel Sherzer and Anthony C. Woodbury (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), pp. 176–239.

24. Bakhtin, 272–73.

25. Humberto Ak’abal, El animalero, Colección Poesía Guatemalteca 5 (Guatemala: Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes, 1990), p. 14; translation mine. An extended discussion of contemporary Mayan poetics is included in Enrique Sam Colop, “Maya Poetics,” Ph.D. diss., State University of New York at Buffalo (1994).