Introduction

It is self-evident that the proposed changes in the electoral procedure will by no means be able to prevent malpractice grounded in lack of knowledge about the electoral procedure as such, or in improper forms of campaigning. The latter, in particular, is illustrated by the recent and disloyal attempts to claim the party label of rival factions as one’s own. Should, however, the freedom allowed for by the current procedure continue to be abused in the future, and should political morale likewise fail to correct such abuse, we are left with no other course than to introduce rules of public candidacy and publicly ratified candidacy lists. (Albert Petersson, parliamentarian. Motion to parliament for reform of the election laws in the aftermath of the Swedish 1911 general election.)1

Political modernization carries with it a number of common features, regardless of its outcome and timetable. As Inglehart (1997: 315) has pointed out, these include a shift in the power relationships of society. Institutions and organizations embedded in pre-industrial traditions and culture give way to new types of institutions and modes of social action. They tie in closely with the state and derive their legitimacy from strictly legal forms of rationality. Simultaneously, new types of association come to the fore as intermediaries between the individual citizen and the state. The political party is among the most important of these.

However, changes of this kind do not necessarily alone result in democratization. Neither is the juxtaposition of ‘tradition’ and ‘rationality’ always an obvious property of political modernization if considered from an empirical point of view. If looked at more closely, this process reveals substantial differences depending on the socioeconomic context. As Barrington Moore (1967) pointed out, the rise of both fascism and communism during the twentieth century bear grim witness to this fact, as does, indeed, more recent developments in the successor states of the Soviet Union. Put simply, the problem identified by Moore and others involves the modes by which constitutional reform and electoral democracy, on the one hand, and grass roots mobilization and democratization of societal values and norm systems, on the other hand, relate to each other.

Included in this issue are questions about the extent to which ‘history matters’: does successful democratization require a gradual and specific sequence of social, economic and political changes across time? Is it the case that new institutions and new types of organizational structures, such as party systems, need to fall into place in a particular order, and must they occur simultaneously with other types of changes, such as industrialization and the spread of literacy? Although ‘sequentialist’ arguments, i.e. the assumption that there exists a universal and linear path to democracy, have been challenged, analysts nevertheless tend to agree that time is of the essence, since time allows for democratic institutions and practices to mature and stabilize (Carothers 2007; Berman 2007). In the case of election campaigns, this is illustrated by my introductory example. Whether changes must necessarily follow upon each other in a particular sequence is, however, a different matter. For instance, a focus on countries such as Britain–a ‘standard model’ of democratization –might, perhaps, be misleading from that perspective. Although British political philosophy exercised great influence on the paths subsequently taken in the Western hemisphere, a comparative approach to countries on the Continent, or Scandinavia in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, enables us to better appreciate the great variation and complexity in modes of political modernization and its organizational framework.

The problem–an outline

Viewed from one perspective, conventional wisdom would hold that Swedish democratization was favoured by certain ancient and deeply rooted egalitarian traditions in society; these somehow thrusting the political system down a path stretching towards ‘classic’ Western-type, liberal democracy (for a recent review, see Andrén 2007: 34–41). Viewed from another perspective, though, such traditions did not immediately transform into a flawless and smoothly working democratic system, once formal institutions started to allow for it. Indeed, the pitfalls and complications implied by linear interpretations of political modernization can be illustrated in several ways. A case such as Germany is likewise difficult to interpret. The ‘Sonderweg hypothesis’, an obvious analogy to the sequentialist conception of democratization, has been thoroughly criticized since the 1980s. As a result it has become less credible as an explanation for the German historical pattern and the turn taken towards totalitarianism (see, for instance, Raulet 2001; Gross 2004: 15–17; Clark 2006: xiii–xvi). The manner in which new organizational practices, and most notably political parties, were introduced in modernizing societies of this kind does, however, offer valuable insights into the complicated relation between institutional change and grass roots democratization.

One of the most prominent features of political association in the late nineteenth century was the gradual replacement of ‘elite parties’ by ‘mass parties’. However, to contemporary society itself there was nothing self-evident about this shift. For example, research has pointed out that the Swedish 1911 elections were peculiar due to the fact that they took place shortly after a reform that more than doubled the size of the electorate, i.e. the extension of suffrage to all male adults in 1909 (women won the right to vote only as late as 1918–21).2 Consequently, the prospect of winning vast numbers of new supporters and votes was apparent to the competing parties, but, importantly, the situation also harboured confusion since mass politics was a relatively speaking new phenomenon in social life (Stolare 2003: 212). The very idea of parties had yet to become widely accepted. Much the same can be said about the development of political parties in Germany or, indeed, many other countries as well, and Sweden was no exception. Hence the topic of this book is about ‘the idea of party’ in a historical context.

In hindsight it is obvious that parties, and in particular mass parties, were finally accepted as a legitimate means of organizing political interests and channelling grass-roots activism: democratization and political participation became, if not unthinkable, in the expression of Aldrich considered to be ‘unworkable’ without parties mediating between the individual citizen and government (1995: 3; see also, for instance, Sartori 1976). The reasons for this were fairly straightforward and reflected the mounting difficulties involved with managing politics once more inclusive rules for suffrage had been introduced. Still, these circumstances beg the important question of which alternative organizational strategies, although perhaps eventually proven obsolete, redundant, and unsuccessful, were put to the test in the face of the challenges brought about by mass politics. In particular the latter is a relevant topic of inquiry since some political movements, such as most notably liberalism, mobilized support and voters quite successfully right up to the beginning of the twentieth century, but on the foundations of organizations that were neither typical elite parties of the traditional kind, nor typical mass parties. In the following chapters I will forward the hypothesis that liberals, for certain reasons, usually favoured organization by proxy. In one sense these proxies were ‘secondary organizations’, but still at the same time not, compared to trade unions and ancillary social organizations, such as recreational and educational societies in the case of the German and Swedish social democratic parties. Rather, liberal parties were normally a part of large, but loosely-knit networks of non-affiliated associations often lacking any formal ties between them. They evolved into a peculiar breed of hybrid organizations in which traits typical to both elite and mass parties were mixed together (chapter 1). The following, therefore, is to no small extent the history of what might have been. It is the history of a partly lost and forgotten trait of democratization, as much as an account of how modern standards of political association slowly fell into place. Considering the complexities of the problem, however, some limitation of scope is necessary, both for practical reasons as well as for analytical purposes.

Scope and rationale of the study

From one point of view, parties emerged as the obvious and natural means of organizing interests and voters in modernizing political systems. Yet, parties and the kind of new political rationality they embodied were often met with considerable suspicion from all ideological camps in contemporary society. Furthermore, right up to the verge of the twentieth century, liberals in particular regularly opted for alternative strategies in order to manage popular and voter mobilization; this because of ideas on citizenship and political association that were typical for liberalism as an ideology (chapters 1 and 2). Circumstances such as these are not sufficiently explained by standard organizational models of party formation: in other words, I cannot agree with the influential remark made by Maurice Duverger that the ideas and doctrines of parties are a subordinate factor, once the organizational structures have developed (Duverger (1967) [1954]: xiv–xv).3 Rather, the process must be understood with respect to the relationship between ideology and organizational practice. More precisely I will devote my attention to the organizational behaviour of liberal movements in Sweden and Germany. The focus will be on the 1860–1920 period, although analyzing the historical background conditions of the idea of party will necessarily involve peering back, in certain respects, well into the eighteenth century.4

Liberalism as such represents an intriguing organizational problem; suffice it here to say that the tension between individual action and collective behaviour inherent in all organizations was brought to an extreme in the case of liberalism, ultimately because of ideological factors. Although successful from the outset, in the long run liberalism somehow ‘failed’, in both Sweden and Germany, in part because neither movement made the last, critical transition, to that of tightly-knit, mass-based party. In the first case liberalism lost momentum somewhere between the appearance of nineteenth-century middle-class radicalism, and the gradually more successful grass-roots organization of voters into the Social Democratic Party by the beginning of the next century. Emerging class-based political cleavages, weak middle classes, and the introduction of universal suffrage were part of the picture (Therborn 1989; Stråth 1990b). However, these factors do not provide the entire explanation. In the second case liberalism not only lost ground to socialism. It also became, in the apt expression of Sheehan, more and more ‘illiberal’, and ended up, somewhat oversimplified, as a pawn of bourgeois and state-centred authoritarian politics (Sheehan 1978; see also Gall 1975).

Firstly, though, these interpretations of liberalism are not entirely justified in light of more recent research.5 In some parts of both countries liberalism succeeded in retaining vital traits. Still without support from a centralized, mass organization, it remained able to consolidate enough popular support to secure a prominent and occasionally dominant position in public life and politics for an extended period. Organization by proxy was arguably an important part of this pattern. Yet, historical explanation is never contingent on one, single factor. Political association does not occur in a vacuum. Therefore the study of alternative modes of organization logically extends into an analysis of the relationship between organization and liberal ideology on the local level. From that perspective I will stress the contribution of socioeconomic and cultural peculiarities in the local environment to specific modes of organizational behaviour.

Secondly, circumstances such as these favour a comparative approach, since this allows for gauging more precisely how uniquely different such alternative organizational strategies really were, and precisely how singular different paths of political modernization actually were when scrutinized more closely. Sweden and Germany, countries that epitomize extremely different outcomes of political modernization are suitable for contrasting against each other from that point of view. An in-depth analysis of liberal party formation processes in two entire countries, during a period which encompasses more than one century, is not feasible for practical reasons, though. Furthermore, neither is the choice of countries as the actual units of analysis obvious. Rather, I execute a study of regions, whereas the national level is considered in terms of historical, ideological, and institutional context.

It could be argued that a focus on regions rather than countries imposes limits on how far the results of empirical study can be extended. From one point of view that is, of course, true. At the same time a state-centred perspective, too, tends to be biased when considering the period in question. By the mid-nineteenth century the European nation-states were not wholly consolidated and, not least in such cases as Italy or Germany, still in the process of emerging in terms of political communities. Similarly the parties first to emerge were, generally speaking, local in origin and make-up. Also, modern means of nationwide mass communication were still developing and, for instance, the nomination of candidates and electoral mobilization, i.e. two of the most important tasks of modern political parties, were coordinated on the local and regional rather than the national level. Party systems formation and political practice were different due to regional factors, even in cases where the institutional conditions were otherwise the same (Lipset & Rokkan 1967; Daalder 2001). Parties were therefore not homogeneous bodies with respect to organization or programme. Arguably, this was the case in Sweden at least until the end of the century. A similar pattern, only far more extreme, was typical in Germany, too, because of its long history of political and cultural fragmentation (the federalist traits of the German state are the perhaps best illustration of this feature; see, for instance, Koselleck 2000).

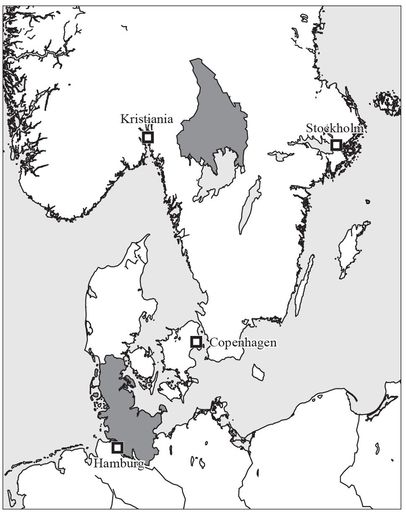

For these reasons I have selected two regions for the purpose of my study. These are the province of Värmland in western central Sweden and the Prussian, formerly Danish, province of Schleswig-Holstein (Map 1). Thus we are dealing not only with two very different countries but also two very different regions. To begin with, however, the modest level of urbanization in large parts of Northern Europe, as well as the relatively speaking late advent of industrialization, must be considered. Together with institutional factors, such as constitution and the design of the electoral system, these particularities played an important part in shaping emerging party systems. This was the case not least in regard to liberalism. True–similarly to the situation in other countries, Swedish liberalism first emerged, in the early nineteenth century, as part of post-1789 urban, middle-class radicalism. Yet, by the turn of the twentieth century, it actually drew most of its support from voters in rural constituencies (chapter 1).

Hence it should be stressed that liberalism in Sweden to a great extent developed under conditions which differed from those more commonly associated with the formation of liberalism, viz. urban and industrialized environments. All other historical, cultural, and institutional differences between Värmland and Schleswig-Holstein set aside, this is an important feature that the regions have in common. Värmland and Schleswig-Holstein differ from each other in almost every possible respect except one: they both have a historical tradition of above-average strong liberal movements, but movements which unfolded in a rural rather than an urban–industrial setting.

Map 1. The two regions, shaded black.

Regions that are extremely dissimilar are therefore analyzed in search of a plausible explanation for one common feature.6 Put more succinctly, the common feature in question (i.e. the ‘dependent variable’) is successful political mobilization, as indicated by high levels of liberal voting turnout in the 1860–1920 period. There should, hypothetically speaking, be at least one common quality (or ‘independent variable’) that helps explain the electoral successes of liberalism in both of my two otherwise different regions.7, 8 Presumably ideology may explain negative attitudes to party in both Swedish and German contexts on a more general level. Yet other dimensions must, however, also be explored. Therefore, if we assume that organizational efficacy is, if not decisive, at least incremental to a mobilization of voters, organizational practice and, thus, the regional perspective are brought into focus.9

The main question pursued in the following chapters is therefore formulated in the following manner: how did liberals go about managing political association in Värmland and Schleswig-Holstein respectively? Answering this question requires a closer historical and qualitative reading of three related issues. Firstly, what was the ideological and institutional context of Swedish and German liberalism? Did Värmland and Schleswig-Holstein somehow differ in comparison to the national level in this respect? Secondly, which were the main features of liberal organizational practice on the regional level? Does evidence render support to the hypothesis of organization by means of proxy? Finally, which additional factors beyond purely organizational ones might help explain the success of liberalism in Värmland and Schleswig-Holstein? What of the importance of the overwhelmingly rural character of both regions in relation to civic and political association?