VI. A PRODUCTIVITY BONANZA

VI. A PRODUCTIVITY BONANZA

The automobile industry was at the leading edge of the nation’s astonishing increase in manufacturing productivity. Consider again Henry Ford’s 1913 production: he produced nearly half of all automobiles produced that year, but with only a fifth the number of workers as his competitors. By 1929, all the automobile companies that mattered had adopted “Fordism” and had improved it. At GM, for example, Sloan and the central engineering staff had vowed they would never get caught in the kind of changeover hell that Ford had endured in 1927, and they had organized their plants around that objective, most especially by designing machinery with flexible tooling to adapt to different size parts.

The deeper productivity transition that underpinned Fordism was the marriage of electricity with mechanical production. In the mid-nineteenth century Samuel Colt’s pistol factories were considered the apex of manufacturing technology. They were beautifully and thoughtfully laid out. They used a blend of special-purpose and flexible machinery, with a high degree of automation for the time. But productivity was drastically limited by their dependence on centralized coal-fired steam power connected to working machinery by belts and shafts. All the drive shafts turned all the time, although individual machines could be disconnected and reconnected. If the main drive shaft into a factory floor was interrupted for any reason, all the machines went down. Machines were necessarily grouped by their weight and torque to align them with the appropriate shafting and belting. Belting often drove shaft arrays on multiple floors, requiring elaborate belt towers. As belts loosened, precision was lost. Oil cylinders were located in factory ceilings to dribble oil on belt arrays to keep them flexible, ensuring slippery, greasy floors. The shaft and belt arrays blocked natural light and made it impossible to clean ceilings.

It took about twenty years after the advent of inexpensive AC power for manufacturers to realize its enormous efficiencies.* The first companies to embrace electrical power were textiles, print shops, and other businesses in which cleanliness was important. Typically, however, nothing changed but the power plant, which still drove the old system of shafts and belting. In the early 1900s, GE developed a “group” approach to power management. Recognizing the absurd inefficiency of driving all shafts all the time, they divided a large plant into units, each of which was powered electrically. The final step came mostly in the 1920s with the adoption of “unit-drive” layouts, in which each machine had its own electrical power source. It was also about this time that large electrical utilities began to market the advantages of unit-drive factory power, even providing free engineering consulting on the conversion process.

The obstacles to full unit-drive conversion were formidable. Virtually all the machinery had to be replaced. Variable-speed machinery needed DC power. (AC power could run DC machinery, but there was a loss of efficiency.) But the advantages were so patent as to be irresistible. The power savings were palpable, but the biggest opportunities were in the intangibles. Unit-drive machinery released the factory layout from the tyranny of the shafting design. Machinery layout could be freely changed to conform to the sequence of production flows. Without the massive shafts and shaft gearing, factories could be constructed of lighter and cheaper materials. One-floor factories were more suitable to straight-line flows, and cheaper than multiple-floored plants. Ditching the liana forests of ceiling shafting made for brighter, much cleaner plants with windows and skylights. Empty ceilings were ideal venues for overhead cranes. Factories could be readily expanded or contracted, without worrying about the distance from the central power source.

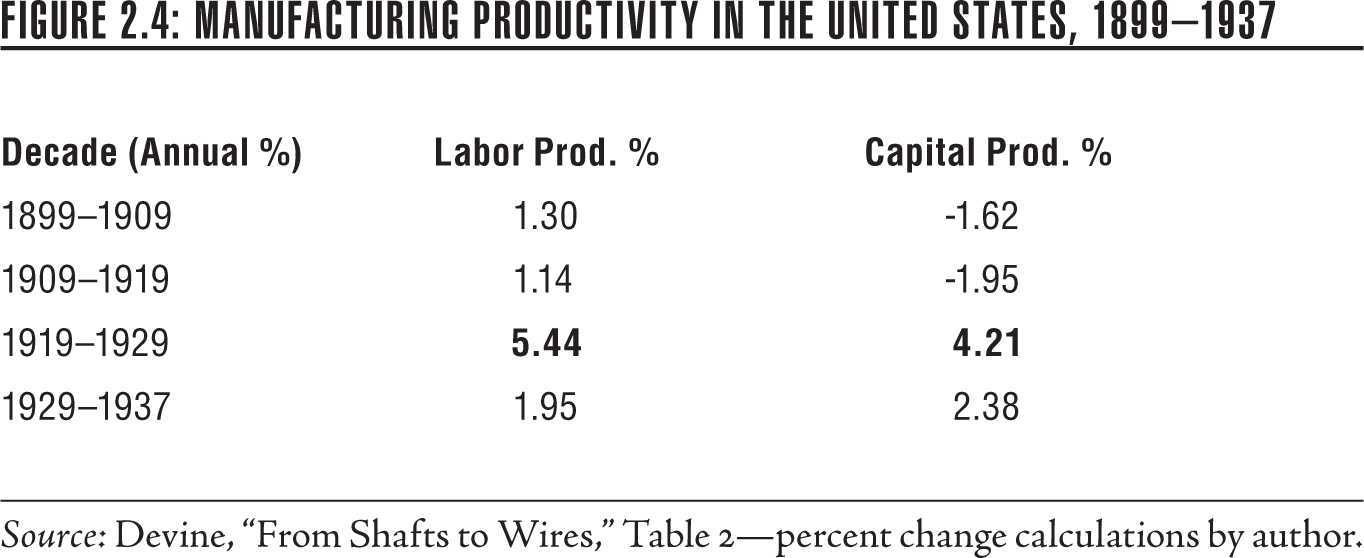

It was Ford, of course, that plowed the visible trail in all these areas. Big companies appeared generally on board with the new approaches during the war, although this doesn’t show up in the statistics. The Lynds’ reports on Muncie, Indiana, in the mid-1920s, however, suggest that Fordism had penetrated nearly all their manufacturing establishments, since the majority of skilled workers had been supplanted by nonunion workers tending smart machines. That may be a biased sample, since Muncie was primarily a supplier to the automobile industry. But the national data show a stunning burst of manufacturing productivity (see Figure 2.4).42