X. ON THE EVE OF THE CRASH

X. ON THE EVE OF THE CRASH

As the United States entered its seventh year of rapid growth in 1929, the country’s businesses looked unstoppable. Car sales, which had become an economic bellwether, got off to a fast start, with a host of attractive new models. In 1922, the industry had sold 2.5 million new cars and trucks. That jumped to 4 million in the banner year of 1923 and, except for 1927, when Ford was out of the market, new car and truck sales averaged just above 4 million. But in 1929, they hit 5.3 million, a jump of about a quarter. Steel plants were running over capacity. Electricity sales were up by 12 percent, electrical machinery sales by 30 percent, machine tool orders by almost 20 percent. Radio audiences were growing apace, and the new talkies were packing them in at the theaters. Big cities were sprouting skyscrapers. There was stunning growth in both worker and capital productivity and no inflation to speak of.

Was there a bubble in stocks? The great contemporary economist, Irving Fisher, thought not, since the momentum of corporate earnings suggested that prices were fully justified. John Kenneth Galbraith’s famous 1954 book, The Great Crash, 1929, makes the case for a “great speculative orgy,” which for many years was the traditional view.57

The Galbraithian logic was supplanted in the 1960s and 1970s by “efficient market,” theorists who begin from the premise that free market prices always best represent the current state of knowledge. Efficient market theorists believe that bubbles are impossible by definition, although the debacle of 2007–2008 may have dispelled the blind faith in efficient-market ideologies.

Barrie Wigmore, former head of research at Goldman Sachs, has produced the most complete microhistory of the 1929 stock market crash. He suggests that there is “room for debate” as to whether stock prices were excessively high in the first half of 1929. The Dow Jones Industrial Index had settled into a trading range of 300–320, or a price/earnings multiple about twenty-four times the anticipated 1929 profits. That was high by historic standards, but not crazy, given the apparent momentum of the economy.58

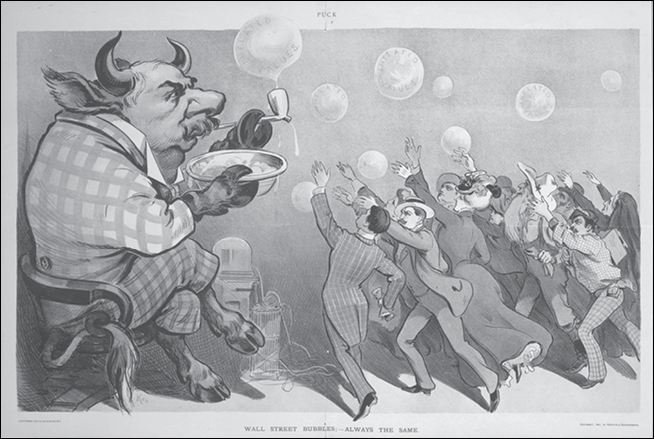

A caricature of a “bullish” J. P. Morgan blowing stock market bubbles attests both to the prominence of the Morgan Bank (J. P. was long since dead) and the skepticism toward the market’s sustained rise.

But the third quarter developments, Wigmore suggests, crossed the line into Galbraithian territory. Starting in late summer—when Wall Streeters were normally on the beach—the market turned decisively up, peaking at 381 on September 1. Signs of “irrational exuberance,” in Alan Greenspan’s famous phrase, had been building for some time. The number of brokerage offices—devoted pushers of stocks to retail customers—had jumped from 706 in 1925 to 1,685 by the fall of 1929, with almost all of the increase coming since 1928. Trading volume increased dramatically, from a daily average of 1.7 million in 1925, to 3.5 million in 1928, and 4.1 million to mid-October, 1929. New issuances of common stock in 1929 were two and a half times higher than in 1928, and more than six times higher than in any previous year. The great majority of 1929 issuances, moreover, were not for new shares but for highly leveraged investment companies aiming to invest in existing shares, in some cases their own shares. The price-earnings multiples for some high-flying stocks soared into the hundreds, some into the thousands. Columbia Graphophone sold at a 5,000+ multiple in September. Foreshadowings of the dotcom boom.59

Brokers jacked up sales with easy credit terms. The average retail customer could buy on 25 percent margin—that is, borrowing 75 percent of the purchase price. (Margin regulation came only with the New Deal securities legislation.) Regular customers routinely bought on 10 percent margin, and many had open credit lines with brokers and put up no cash at all. Securities lending to brokers and other investors grew from $3.3 billion in the spring of 1927 to $8.5 billion in October of 1929, or about 8 percent of GDP. After mid-1928, 90 percent of such lending were “call loans,” that the lender could close out at any time—an important source of instability. To make it worse, almost 80 percent of the lending came from nonbanks. The Federal Reserve had clamped down on brokers’ loans by banks, so corporate treasurers, investment funds, or anyone else with loose cash rushed in to scoop up loans paying annualized rates of up to 20 percent. The flood of new lending, of course, was purely opportunistic, so loans were called in at the first hint of trouble.60

The hucksterism was especially flagrant in the late stages of the 1929 stock run-up. There were more than a hundred new issuances that were organized by market professionals, usually comprising bundles of stocks, for the sole purpose of artificially pushing up prices. Tip sheets followed their every move and blared their virtues to naïve investors, who were left with the losses after the professionals made their exit. As Pecora’s and other investigations showed, Wall Street’s interlocking depositary and investment banking businesses were ripe fields for self-dealing, gross fiduciary violations, and rampant greed. When Clarence Dillon of Dillon, Read was asked how the insiders on a Dillon, Read flotation could justify their disproportionate share of the profits, he seemed mystified: “We could have taken 100 percent. We could have taken all that profit.” A senator on the panel quoted Lord Clive of India’s comment in his corruption trial: “When I consider my opportunities, I marvel at my moderation.”61

Two 1990s papers by senior economists measured the degree of overpricing by comparing changes in the prices of shares to roughly comparable instruments. In the last stage of the closed-end fund craze in the late summer of 1929, the closed-end funds were 50 percent more expensive than the individual shares in their portfolios, which makes no sense at all. The second paper tracked the interest cost on broker loans to buy shares. When the Fed cracked down on brokers’ loans in 1929, interest rates soared to 20 percent or even more. In normal times such a heavy cost of carry would cause a sharp market break, purely on the economics. Following the math through suggests a market bubble of about 30 percent. Still other research supports market plungers. A 1975 paper applies Burton Malkiel’s well-known formula for forecasting price/earnings ratios of the stocks in the Dow Jones Industrial Average, and finds that, while there was “some over-indulgence… by the usual standards for such things, the conclusion would have to be: not much of an orgy.”62

Allan H. Meltzer, in his history of the Federal Reserve, provides an arresting comparison of net corporate profits to the market capitalization of shares listed on the New York Stock Exchange. While real GDP rose strongly through most of the 1920s, corporate profits rose three times as fast. The ratio between stock capitalizations and net profits was 6.2 in 1925 and jumped to more than twice that by 1929. But almost all of the repricing had happened by 1927. The market cap/profits ratio dipped through much of 1928, but recovered in 1929, to slightly ahead of its 1927 high, based on the boffo first-half growth in revenues and profits. Even on Meltzer’s comparison, stocks still could be considered high in the fall of 1929; that peak market cap/profits ratio has since been exceeded only twice.63

There were certainly conflicting signals. It is a commonplace among historians of the crash to say that industrial production had turned down after June 1929. Technically, that’s true, as Figure 2.6 shows. But the question is whether anybody noticed it.

Industrial production peaked in June. The June data are dated July 1, but could not have been compiled and released until well into July,* when they were greeted with unalloyed cheering. Here is the commentary from the July Survey of Current Business:

The general index of manufacturing production in June… was higher than any other month on record, showing a gain of more than 2 per cent over the preceding month and almost 15 per cent over June of last year.…

Wholesale trade in June… showed a decline from May but was greater than a year ago.… Sales by department stores… were greater than in either the preceding month or June of last year.

Sales by mail order houses in June were substantially greater than in the preceding month or the corresponding period of last year.… Sales by grocery chains in June… showed a considerable gain over a year ago. Ten-cent chain-store systems reported a gain of more than 13 per cent over June, 1928.…

The total production of automobiles, both passenger cars and trucks, during the first half of 1929 was larger than in any other period on record. Exports of automobiles from the United States in June were greater than either the preceding month or June of last year, with the total for the first half showing the largest external trade than in any other similar period. Imports of crude rubber in June showed a decline from the previous month, but were about 50 per cent higher than a year ago.64

July was a little less exuberant, but had the aspect of a modest slowdown from the torrid pace of the first half. Pig iron was up, but sheet steel (driven by autos) was down. Fabricated structural steel (skyscrapers) was up strongly, as were steel castings. Coal continued to slip, as it had been doing for a long time, but petroleum products were hitting new highs.65 It is only in the September report, released in mid-October, that the slippage becomes visible, but it’s far from dire. The Survey data is in the form of index numbers, using the averages for 1923–1925 as 100. Total manufacturing, which included textiles, packaged foods, cement, petroleum products, as well as iron and steel and machine tools and automobiles, had opened the year at 117, peaked at 128 in June, then slipped to 122 in September, with no obvious trend. Automobiles had been on a tear, opening the year at 121, before shooting up to 188 in April, then dropping back to 127 in September. Steel ingots had opened at 121, risen to 153 in May, and fallen to 130 in September. Electric power was at 159 in September, close to the average for the year. Factory employment was flat. While the summer cool-down in the enormous metals and metal products industries was evident, little else in those reports suggested a collapse. As Bethlehem’s Schwab remarked with some puzzlement in the first days of the market break, steel factories were running at 110 percent of capacity, with healthy backlogs and no inventory buildups.66

The falloff in the industrial production reports, which was a broader index, doesn’t really raise alarms, even with 20/20 hindsight. The blowout June number, 138, was the highest ever, and by the September report, which wasn’t released until mid-October, had only dropped to 135. The collapse in October was clear, of course, but those reports weren’t released until November and December. The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) later placed the 1929 business cycle peak in August.67 A number of professional traders, however, had long since seen enough, particularly if they were following events in Europe, where economies had been turning down for some time. Bernard Baruch and Percy Rockefeller, a nephew of John D. and an active investor, were selling shares in early 1929. John Raskob had dumped almost all of his GM and DuPont shares starting in 1928. Certainly by September a number of broker newsletters were warning of a correction.68

A fair conclusion is that the market was too high in the late summer and early fall of 1929, and was due for a correction—which duly happened. But as Galbraith remarked, “it is easier to account for the boom and crash in the market than to explain their bearing on the depression which followed.”69