III. CHARTING THE FALL

III. CHARTING THE FALL

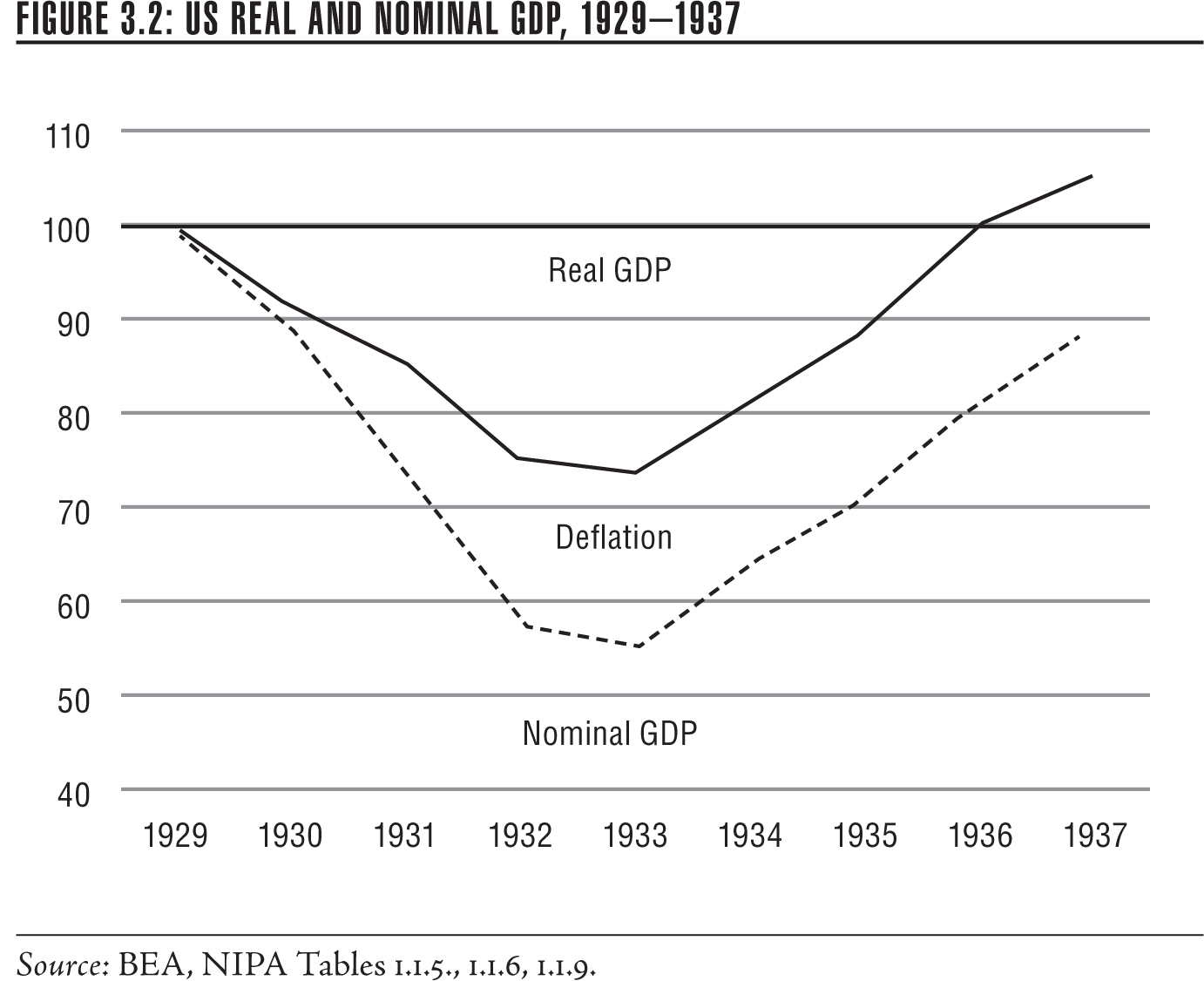

Measures of national economic growth are usually presented in “real” numbers, stripping out the effects of price changes. Five percent nominal GDP growth, in a year when prices rise by 3 percent, is logged as 2 percent real growth. The economic collapse that commenced in mid-1929 was accompanied by a downturn in prices on top of the steep fall in GDP. From 1929 through 1933, measured annual GDP dropped by a crushing 45 percent, but that collapse had two components—a 26 percent drop in real output, and a 19 percent fall in prices (see Figure 3.2). Factoring out the change in prices, real GDP had recovered to its 1929 level by 1936, although that was hard to explain to the man in the street.

The name of Irving Fisher still lives in infamy. He was the famous Yale economist who confidently assured the world in 1929 that the stock market had reached “a permanently high plateau.”17 That lapse aside, he was one of the greatest of the moderns, arguably on a par with Keynes, and was one of the first to explicate the peculiar horrors of deflationary downturns. Debts outstanding do not adjust with changes in price levels. If both the price index and the wage index drop by half, workers’ relative purchasing power doesn’t change, but the weight of any preexisting debt will double. Deflation by itself isn’t the problem, it is the mountain of unpayable debt that it leaves in its wake. Debt defaults cause a contraction of deposit currency, so the money supply shrinks and prices keep falling. The “swelling” dollar causes currency hoarding and further contraction. Or, as Fisher puts it in his 1932 book, Booms and Depressions:

That the dollar disease—falling prices—is the main secret of great depressions is confirmed by the observations… that depressions last three or four times as long when prices are falling and are very short when, by some good fortune, an up-tide of prices intervenes.18

Fisher used the term “dollar bulging” to describe the increase in each dollar’s purchasing power during a deflation. The flip side is that discharging a $1,000 home mortgage assumed in 1929 would require the purchasing power of $1,200 in 1933, even though most paychecks would have adjusted downward to reflect falling prices. Once underway, the deflationary process feeds off itself. Companies default on their debts, banks start reining in credit, production slows, and people are laid off.

The worst possible reaction to a deflationary depression, Fisher continues, is to “balance the budget,” because it always entails reducing spending and/or raising taxes, either of which worsens the deflation, since it is extracting spending power from the economy. A 1932 Hoover tax increase came when “each dollar was already 60 per cent more burdensome to the debtor than in 1929.” If the government had instead commenced borrowing and spending to reflate prices, it “would have lowered the real debts, public and private, by lightening the real dollar.”19

The modern picture of a deflation is more complicated than Fisher’s. Deflation increases the “real balances” of households; when prices fall, the cash in your cookie jar, and the national money supply, is worth more. But those happy effects are counterbalanced by the contractionary real burden of debt. In addition, if investors’ expectations of future prices go down with no change in the interest rate, real interest rates will have risen. The Fed kept its interest rate low during the Depression, usually at or near 1 percent, but the real rate, taking into account the appreciating real value of the future payoff stream, was 10–12 percent or even higher. Investors were not fooled and real investment collapsed. In index numbers, gross domestic investment fell from 100 in 1929 to only 16 in 1932. Keynes, while agreeing with the Fisher deflationary story, points to its impact on investment as the real cause of the collapse.

Fisher’s model of the monetary system was updated in the famous Milton Friedman-Anna Jacobson Schwartz Monetary History of the United States (1963). Total spending, and the price level, is a function of the money supply times its velocity, or annual turnover rate.* Friedman and Schwartz defined “high-powered money,” or the monetary base, as gold, currency in the hands of the public, bank vault cash, and member bank deposits at the Fed. The deposit-reserve ratio was the money multiplier, since banks could lend multiples of their deposit base. Friedman and Schwartz’s third variable of interest was the deposit-currency ratio. Before the advent of deposit insurance, people converted deposits into currency in times of crisis. While that increased the monetary base, the net effect was depressive because it lowered the volume of deposits subject to the money multiplier. Currency hoarding was rife in 1932 and 1933.20

Federal Reserve System rules required that member banks keep an average of about 10 percent reserves against their deposits. Such reserves, in the form of gold, cash, and good commercial bills, or, after 1932, government securities, were deposited with their respective federal reserve district banks, which in turn were required to hold 35 percent reserves against them. The Fed was not a passive player. If it actively supplied new reserves to the system, it could generate up to thirty times that much in new economic activity. (New Fed reserves will support approximately three times their amount in new member bank deposits, which in turn could generate ten times the added deposit value in new lending.) That is the magic of the “money multiplier.” And the Treasury and the Fed had the power to create as many new reserves as they pleased—for example, by running a budget deficit, financing it by selling debt securities to the Fed, and using them to support new deposits and more aggressive lending.21

Friedman and Schwartz are scathing in their treatment of the 1930s Fed, and suggest that the Fed could have arrested the deflation by injecting $1 billion or so of liquidity into the banking system. The time to do that was in 1930 when banks were displaying signs of weakness but before the deflationary momentum had really taken hold. They blame the failure to do so squarely on the Federal Reserve, and speculate that if Benjamin Strong, the savvy and charismatic president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York had been alive—he died of tuberculosis in 1928—he could have substantially moderated the Depression’s course.22

That is unlikely. It is far from clear that Strong was an inflationist, but even if he had been, he would have faced powerful opposition. The estimable banker Paul Warburg, for example, was convinced that easy money was the root of the crisis. Lester Chandler, an early historian of the Fed, calculated that in mid-1931, when the Depression was markedly deepening, only two district bank boards favored monetary easing, seven were completely opposed, and three were undecided.23

The deeply dug-in opposition to monetary solutions is illustrated by Oliver M. W. Sprague, arguably America’s leading monetary expert. He was professor of banking and finance at the Harvard Business School and an adviser to both the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England. His 1910 History of Crises Under the National Banking System is a seminal work even today. The editors of the New York Times commissioned him to write ten long features in November and December 1933, an extraordinary allocation of editorial space that attests to Sprague’s eminence. Sprague is very clear:

I do not believe that the depression is primarily due to monetary causes, and… I hold that no monetary policy, however wisely formulated, is sufficient to bring about a trade recovery. We had sound money and no doubt about the security of the currency between 1929 and 1933. There was also during those years a plentiful supply of credit available at low rates and at intervals widespread confidence that prosperity was at hand; and yet the country drifted more and more deeply into depression.…

The essential problem, then, of trade recovery is to develop conditions under which industry will absorb the millions who are now out of work and find a continuing and profitable demand for a very much enlarged industrial output.

We already have a supply of money amply sufficient to support far more credit and currency than would be required with full employment, active business and a level of prices and money incomes far above those which obtained in 1926.24

From the modern perspective, the wrong-headedness seems striking, but is much less so from the vantage point of contemporaries. In the 1920s, Keynes was as yet little known in America—his Treatise on Money was published only in 1930—while Fisher’s Booms and Depressions saw the light of day only in 1932. Practical bankers had long since internalized an informal collection of “sound banking principles” centered around a strong bias against deliberate inflation. (Just as deflation increases the burden of debt on borrowers, inflation reduces the value of loans on bank balance sheets. Farmers love inflation because it’s easier to pay off their crop loans.)

The fear of inflation was not merely purblind, for it had centuries of history behind it: debasing the coinage was the surest sign of a failing king. Recent experience ringingly confirmed that ancient wisdom. The United States experienced a nasty deflationary crash in 1920–1921. The government deliberately did not reflate the economy, and there was a rapid recovery, followed by a sustained period of high-productivity growth. At about the same time, there was a depression in Germany, where the banking authorities and their masters in the government chose an opposite strategy. Instead of allowing the market to take its course, they reflated aggressively and created a legendary monetary disaster. In 1920–1921, the value of the Reichsmark (RM) fell from 320 DM/$1 to about 4 trillion RM/$1, not that anyone was really counting. Only a brave theorist could recommend a strategy of reflation; for an empiricist, the case was closed.

Timelines are compressed by historical memory. The American story therefore becomes: the stock market crashed, and the Great Depression ensued. But that’s not how it appeared at the time. Professionals knew that the stock market was only a tenuous proxy for the real economy, which in 1930, seemed in pretty good shape. Yes, the big jump in automobile production in the first three quarters of 1929 was overdone, leaving the industry with at least an extra quarter’s excess inventory. A slowdown, and a mild recession, was very likely in the cards, but there were still a number of positive indicators. The 1929 unemployment rate was down to only 2.9 percent, one of the lowest ever. Radio and talking pictures were still in a high-growth mode. Air travel was on the brink of a boom. Rural areas were still underserved by electricity. Older manufacturing cities had severe housing and infrastructure problems. Corporate profits were strong, and prices were well-behaved. A reasonable scenario looked like a modest slowdown to realign the real economy, followed by pickup in the financial markets.

And at first, that looked like what was happening. The indicators in the June 1930 Survey of Current Business, reporting April data, were below the unsustainable 1929 results, but felt like a pause, not a collapse. The Survey data are in the form of index numbers, taking average output for 1923–1925 as 100. In the red-hot spring of 1929, automobile production hit 188, but dropped off a cliff in November, December, and January (65, 36, and 83 respectively). By April 1930, however, production had recovered to 134, within a whisker of average production for all of 1929. Steel and pig iron had rebounded to their 1928 levels, although manufacturing as a whole had slipped to its weaker 1927 pace, and factory employment was down about 8 percent from 1929. The stock market seemed to be regaining some confidence: the index of industrial stocks had rallied to 279 in April, or just below the 286 average for April 1929.25

Hoover instinctively threw himself into heading off a recession, to the almost universal praise of businessmen. Starting in November 1929 and extending through most of 1930, he held rounds of meetings with businessmen, governors, mayors, private associations—whoever would listen—urging that businesses maintain wages and that states and cities accelerate their inventories of construction projects to stabilize spending and employment. Hoover has been criticized for not wielding the federal spending club, but that was a chimera. The federal government accounted for only about 4 percent of GDP, with much of it devoted to the military. The states and the cities were still where real spending power lay.

Hoover’s grasp of the potential power of government spending to offset business downturns was proto-Keynesian, well before all but a narrow elite had heard of Keynes. His economic instincts, however, were waylaid by his scruples against expanding the federal government, his fear of inflation, and his emotional attachment to the gold standard. Beyond that, he had a cherished illusion that his successes in relief work stemmed from marshalling private resources, ignoring how much of his support came from allied governments.26 None of his initiatives in coordinating private resources by businessmen, or by local governments, were successful. The best that can be said about his term in office was that he left behind a few promising interventional ideas, like the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, which was empowered to make federal loans to banks and businesses, that were later exploited, if only occasionally acknowledged, by the New Dealers.