II. THE GOLD STANDARD

II. THE GOLD STANDARD

The most astonishing construction of the Victorian era was what the historian John Darwin has called the British World System. It was not so much a conscious creation as an organic evolution of assumptions, institutions, and practices, maintained for the most part by private parties seeking private interests, within broad boundaries established by the government. Its physical expression was the system of long-distance sea lanes, monitored and protected by the Royal Navy, tied together by a vast port and shipping infrastructure and the world’s deepest financial network. Like some huge but usually benign spider, Great Britain sat on top of a global web of trading relations stretching from Hong Kong, New Delhi, and New Zealand, to Russia, Central Europe, Persia, and Egypt, to Argentina, Brazil, and North America, as well as to nearly all the accessible dominions of Africa.

The Industrial Revolution of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was almost exclusively a British phenomenon. As Great Britain gave over more and more of its economy to manufacturing, its exports shifted to finished textiles, steam engines, machine tools, and rolling stock, and its imports to basic commodities, like cereal grains, iron ore, and lumber. As its trade sector grew apace, it naturally became the global leader in accountancy, law, shipping, finance, and other high-end commercial services. The combination of a frugal government with its sizeable streak of adventurous, inventive, and entrepreneurial people led directly to the accumulation of immense amounts of capital.

Financial settlements were mediated by a deep network of city finance houses that bought and sold mostly sterling trade bills,* the majority of them with no British parties on either end of the transaction. At moments of temporary stringency, a rise in the London bill rate would quickly pull in investors from the United States and the continent to make up the shortfall. The top London finance houses also worked at the long end of the market, deploying the country’s capital surplus in great exploits of project finance; building the world’s canals, dams, water systems, and railroads; and reaping big upfront placement fees and long-term streams of interest and dividends. The proceeds of those global bond and stock placements were usually deposited in those same London banks, adding to the city’s liquidity. Finally, if funds were really tight, the chancellor of the exchequer could always place paper with its Indian colonial administration, which typically had large trade surpluses (cotton, spices, tea) with the home country.1

In his classic 1873 tract, Lombard Street, Walter Bagehot, the long-time editor of The Economist, provided a veritable handbook of advanced nineteenth-century central banking. The management of a nation’s gold reserve was a central concern. A trading nation like Great Britain must keep a sufficient reserve of legal tender, either gold or reserves of currency readily convertible to gold. The challenge to be met was that “foreign payments are often very large and very sudden… [a] bad harvest must take millions in a single year.” The primary weapon in the central banker’s armory, the “effectual instrument,” in Bagehot’s words, “is the elevation of the rate of interest:”

Continental bankers and others instantly send great sums here, [to England] as soon as the rate of interest shows that it can be done profitably.… The rise in the rate of discount acts immediately on the trade of this country. Prices fall here; in consequence imports are diminished, exports are increased, and, therefore, there is more likelihood of a balance in bullion coming to this country after the rise in rate than there was before.2

The alleged automatic operation of the classic gold standard is the source of its allure. An episode of inflation, whatever its cause, devalues the local currency—it takes more currency units to buy a standard unit of goods. Trading partners at some point will spurn payments in currency and insist on gold. As gold reserves dwindle, authorities are forced to quash the inflationary momentum by raising interest rates or by using open market operations—selling securities to banks to mop up lendable cash. The process was first described by the Scottish philosopher and savant, David Hume, and dubbed the “price-specie flow mechanism.” Some modern conservative politicians, who hope to shrink government, preach that the automaticity gained from a return to a classic gold standard would make the Federal Reserve unnecessary.

The “classic gold standard” actually prevailed for barely a century between the Napoleonic wars and World War I, with a period of admirably efficient operation of perhaps fifty years. The actual workings of Victorian-era finance, however, were quite different from Hume’s hallowed price-specie flow mechanism. Although the pound sterling was nominally linked to gold, sterling, not gold, was the normal settlement currency both throughout the Empire and with most other trading partners. As the system matured, Great Britain almost always ran a merchandise trade deficit with the rest of the world, which it more than balanced by a vast flow of investment returns and other “invisibles” like shipping proceeds. None of this was happenstance. Senior civil servants, leading merchant bankers, and top cabinet members had a roughly accurate grasp of how the system worked, the benefits it conferred on the home country, and how it could go wrong. The gold standard was certainly a critical part of the system, but it was important mostly for keeping non-sterling peripheral countries in line. The list of “peripheral” countries would have included the United States, which for most of its history had to conduct its foreign trade with gold. By the prewar period, however, the dollar, which had been pegged to a specific gold parity since 1879, was gaining increasing acceptance in international commerce.3

Since London was awash in other people’s money, the Bank of England had few liquidity concerns, and so carried only a “thin film of gold” in its reserves, running as low as 2–3 percent of the money supply. Such low cover occasionally caused problems, as in the 1890 collapse of the House of Baring. The Barings were caught with a large position in Argentinian government bonds that had been repudiated by a popular revolution. A failure of Barings would have shaken dozens of major city firms. Foreign and local deposits alike briefly fled the banking system, draining gold. When Russia let it be known that it was reviewing its own deposits, bankers feared for the convertibility of sterling. The crisis was resolved by large gold loans from France and Russia, plus a large additional French gold standby credit. The mere announcements of the loans was enough to quell the crisis and create time for officials to sort out the mess. Roughly the same sequence of events played out during the severe American banking flash-crisis of 1907—the gold standard was maintained because the major gold-using countries pulled together to ensure the Bank of England’s continued liquidity.4

The apparent stability of the gold regime suggested that it would survive even the cataclysm of the world war. All of the belligerents except the United States left the gold standard during the years of active hostilities, and even the United States restricted the sale of gold. But it was taken for granted that when the fighting stopped, some simulacrum of the prewar system would be reconstructed, albeit with an American role more consistent with its great power. All statesmen understood that major wars had no happy endings: financial systems would be in disarray; trade relations would be disrupted; factories, roads, housing, and other infrastructure would be heavily damaged; populations would be dispersed and rootless. But those issues, it was assumed, would become more tractable once there was a shared and updated monetary machinery.

The hoped-for seamless return to the gold standard didn’t happen, for many reasons. For one thing, countries had quite disparate recent histories of deflation and inflation, which colored their attitudes toward growth, and made it difficult to devise mutually agreeable exchange rates. There were also extreme imbalances of national gold holdings, which as a practical matter, had the same effect as actual gold shortages. The halcyon days of the British monetary dispensation had been eased by new mine openings that made gold relatively abundant. In the postwar period, however, the maldistribution of gold was exacerbated by falling production rates. Through the 1920s, average production was about 13 percent lower than in the immediate prewar period.5

Most discussions of gold, moreover, were quickly muddied by the quasi-religious significance attached to gold as the ultimate standard of value—which to the literal-minded was usually identified with the prewar valuations. The wartime inflation had made a nonsense of those numbers. The US dollar gold parity, for example, was $20.67 per fine gold ounce, unchanged since 1879. That number had served until the start of World War I, in part because prices had been remarkably stable over most of that period. By the end of the war, however, maintaining the gold price at $20.67 was a gross understatement of its purchasing power, which persisted even after the US deflation of 1920–1921. Besides reducing the incentives for gold miners, the undervaluation increased the volume of gold required to meet central bank coverage ratios, at the same time as it raised demand for gold in the jewelry industry. Such considerations were merely theoretical when almost all countries were off the gold standard, but raised difficult questions once central banks began to contemplate its resumption.

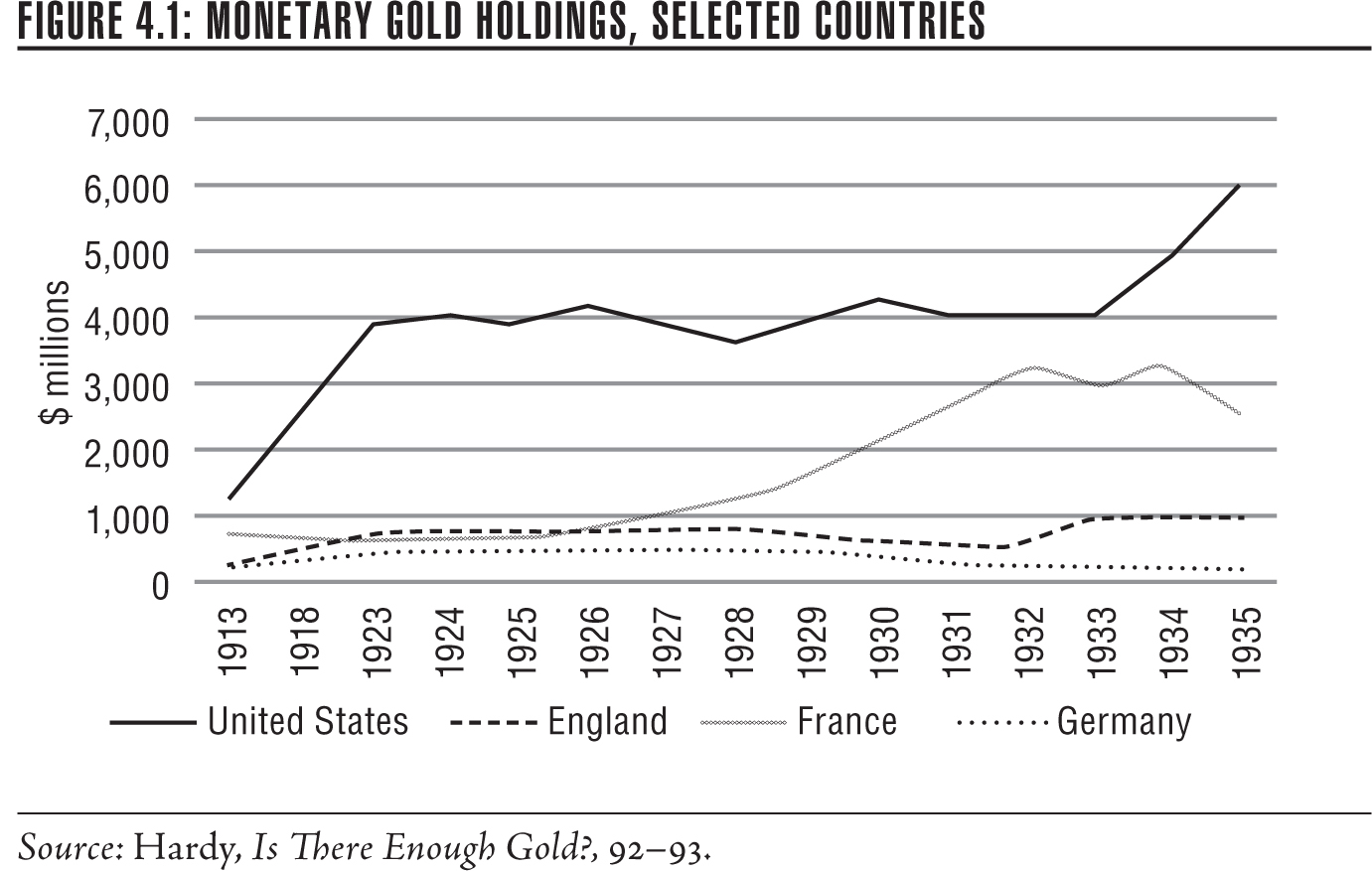

The maldistribution of monetary gold was the most visible issue, but was very difficult to address, since it exposed fundamental contradictions among big-country central bankers.

As Figure 4.1 shows, the US share of monetary gold ballooned through the war and the deflationary episode of 1920–1921, before settling at about $4 billion in 1924. There is a small, barely visible, dip following an episode of easing by Benjamin Strong, the president of the New York Fed, in 1924–1925—both to counter a modest US recession and to facilitate the British return to gold in 1925. There is a second dip following an episode of easing in 1927, again to counter a mild recession and to help the British stabilize their sterling/gold parity.6

Until his untimely death in 1928, Strong was the de facto leader of the Federal Reserve, not only dominating Fed economic policy making, but using his great financial leverage to assist the other major countries to return to a workable gold standard as well. While America’s financial power naturally enhanced his stature, it was Strong’s personal judiciousness and considerateness that made him a natural intermediary in keeping a prickly group of financiers moving more or less together and to similar ends at least most of the time. Altogether, it was one of the happier matches of talent to policy challenges in the annals of American finance. That he failed to achieve his international objectives testifies to the virtual impossibility of the project, given the witch’s brew of hatred and revenge still smoldering on the continent of Europe.7

One of the major obstacles to “resumption,” as the return to gold was called, was the overhang of international debt stemming from the war. To Strong’s embarrassment, the United States was the world’s dominant creditor and by no means an especially accommodating one. Men like Hoover, Strong, and Thomas Lamont, a senior Morgan partner and adviser to the Treasury, understood that a pettifogging US attitude toward European war debts could forestall a world recovery and risk a dangerous depression. But the American Congress and nationalist politicians like Calvin Coolidge, at least in public, expected cash-on-the barrelhead repayment in gold, ignoring America’s already dominant share of the world’s monetary gold supply. The issue of war debts was complicated by the heavy schedule of reparations imposed on Germany and its allies by the Treaty of Versailles, which France in particular was determined to collect, in part to help pay off its war debts.

An international conference, spearheaded by the British, assembled in Genoa in 1922, and while it did not reach a consensus, it aired some useful ideas. The United States did not attend in part because Strong did not want to be besieged by America’s importunate debtors. Ralph Hawtrey, the British Treasury’s monetary expert, advocated converting the gold standard into a “gold-exchange” standard, by which countries would accept the pound and the dollar as gold reserve equivalents, which France naturally took as an insult. Strong let it be known that he was averse to a gold-exchange standard. Among other dangers, overseas buildups of dollar reserves could lead to runs on American gold, which did become a real problem in the 1960s. Several economists, including Keynes, Sweden’s Gustav Cassel, and Irving Fisher, weighed in with various proposals for “managed” gold standards by which gold prices could be adjusted to reflect shifting economic realities. Such schemes gained little traction, however, against the objection voiced by traditionalists like Russell Leffingwell, a Morgan partner and former Treasury official, who argued that restoring prewar gold parities could not be a question of “expediency.” The business instinct on gold parities, he went on, were based “on the sound principle that promises are made to be kept.… [T]here cannot be prosperity without confidence, nor confidence without a fixed measure of values and medium of exchange.” But even Leffingwell conceded that the rule applied only to “any country which can restore its currency to pre-war mint parity.”8

To return European countries to the gold standard, however, required sorting out the positions of the three major European powers—Germany, Great Britain, and France—each of which faced quite different challenges. Germany’s may have been the most daunting.