III. GERMANY, 1919–1925: VENGEANCE, REPARATIONS, AND WAR DEBTS

III. GERMANY, 1919–1925: VENGEANCE, REPARATIONS, AND WAR DEBTS

The Treaty of Versailles was written entirely by the victors: the Germans were shown it only in its completed form and were given only three days to accept it—although that was extended a week. Germans felt aggrieved and angry—but they had invaded Belgium, a neutral state, and on their locust-like march through the country had wreaked atrocities against civilians, destroyed cherished cultural artifacts, and shipped much of Belgium’s industrial machinery back to Germany. Then they fell upon France, killed a quarter of the country’s young men and diligently destroyed its industrial infrastructure. Nor did Germany have any standing to object to reparations. They had imposed heavy reparations on France after the 1870–1871 war, and had recently imposed stinging indemnities on Russia and Romania following their victories on the eastern front.9

But the Germans were determined to pay as little as possible in the way of reparations and preferably nothing at all. The reparations question was necessarily entangled with the question of repaying the very large loans that the Allies owed to the United States and Great Britain. Great Britain, which was both creditor and debtor on the war loans, made a strong case for a general amnesty. Yes, the United States had sent massive amounts of dollars and goods across the Atlantic, but surely they had profited mightily from the war business.

At the Versailles conference, however, delegates floated such phantasmagorical numbers for German reparations, as high as $100–200 billion, that wise heads adjourned the reparations discussion to an expert working body. In the meantime, the Germans were compelled to make in-kind reparations, mostly transferring coal, railroad rolling stock, and industrial machinery. After nearly two years of discussion, the Reparation Commission came up with a total reparation figure of 132 billion gold marks, or roughly $33 billion—the “London schedule” (assuming gold marks at about four to the dollar). It was a fake number—consciously framed to satisfy the “le Boche paiera tout” thirst for vengeance on the part of the French and Belgians. The fine print divided the payments into three classes of bonds. The first two, an “A bond” and a “B bond,” together with a $2 billion credit for German in-kind transfers, totaled $12.5 billion or about a single year’s worth of German GDP. Both the A bonds and the B bonds carried explicit amortization schedules and stringent provisions for establishing sinking funds and other measures to assure payment. The C bonds, with a face value of 82 billion gold marks, or about $20 billion, had no such provisions; indeed, the fine print had so many escape hatches for Germany as virtually to preclude any payments at all. Poincaré commented in disgust, “L’État des payements avait surtout un caractère théoretique.”10

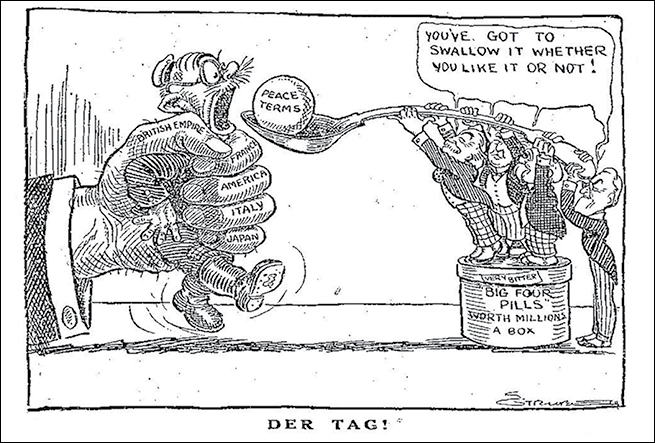

A powerful fist is shown squeezing a hapless German, as the victors use the Versailles process to force Germany to pay, what Germans insisted, were crippling reparations. The reparations, in fact, were no more than Germany had regularly exacted from territories that it had conquered.

The Germans made the required first $250 million payment on the London schedule in mid-1921, with borrowed money that was repaid with export earnings—but that was only because German customs stations were still under Allied occupation. Once the Allies turned over the customs posts, the Germans made only negligible cash payments, but they continued to make in-kind transfers, although typically with deficiencies in the range of 15–30 percent. The British made no secret that their priority was to restart the German economy to drive a European recovery, and consistently opposed serious enforcement of reparations. The French, acutely conscious of their demographic and industrial inferiority, were in mortal fear of just such a German revival; besides that, the German destruction of French coal and iron resources made it impossible to restart French industry without substantial transfers from Germany.11

French dyspepsia worsened in the spring of 1922 when the Soviet and German delegations to the Genoa currency conference repaired to the modest town of Rapallo a few miles distant, and hammered out a commercial and financial treaty. Ominously, that following January, when the French and Belgians invaded the coal-rich Ruhr industrial region to enforce reparations, Berlin and Moscow made joint protests, and the Soviets warned France that they would not tolerate further absorptions of German territory. The occupation itself was a near-disaster. German officials mounted a campaign of passive resistance even as Comintern agents fomented radicalism among the workers. There were waves of sabotage, which were put down violently by the French and Belgian occupation troops, and widespread deportations and abuses of women and children, including “hundreds of rapes,” some of them quite brutal.12

In the meantime, Germany had descended into monetary chaos. As the reality of the Kaiser’s abdication and Allied military victory sunk in, the 1918 “November Revolution,” or “quasi-revolution,” triggered a full year of upheaval: the old aristocracy fell back on their estates, bracing for a French-style revolution; workers’ councils took over factories and even whole cities; marches, political demonstrations, and political-sectarian gun battles disrupted basic services. The social fabric held sufficiently, however, and a constitutional parliamentary democracy, the so-called Weimar Republic, was formed under a center-left socialist government. It immediately enacted a string of expensive reconstruction programs, began to pay property owners for losses from postwar territorial transfers, and legislated big boosts in social welfare provision—an eight-hour day, unemployment insurance, and generous pensions for veterans and war widows. The ambitious spending agenda implied huge budget deficits or major tax increases. Seats in the National Assembly were allocated by proportional representation,* which made it very difficult to push through meaningful revenue increases—so, by default, the government fell back on a strategy of large deficits and rapid inflation.13

The inflationary mechanism was simple enough. The Weimar treasury financed its spending increases with short-term notes that it sold to the central bank for currency. Although the central bank was autonomous, bank management cooperated with the policy of inflation. Since there was no limit to the amount of short-term paper the treasury could create and sell to the bank, there was no limit on the production of new currency. Revenue generated by printing new money soon exceeded revenue generated by taxes and fees. Since money was essentially free, a left-leaning government curried political favor by expanding its social provision.14

For at least the first year or so, many Germans made out very well from the inflation. German industrialists had been heavily leveraged at the war’s end, and rejoiced as inflation blew away their debts. Exports soared, as the plunge in the Reichsmark secured Germany’s position as the low-cost producer. Foreign investors, accustomed to Prussian punctiliousness in paying debts, snapped up German bonds. From 1920 through mid-1922, when prices first became totally unmoored, perhaps $1 billion flowed into the country, most of it from America. About half of it purchased real goods and the rest was lost in the inflation. Prior to that, however, the industrial revival had stabilized the mark at about 65 to the dollar, compared to the prewar dollar-gold parity of 4.2 marks. The rich cream of the recovery redounded primarily to the owners, but under the Weimar governments a decent portion of the drippings percolated down to workers, with the largest benefits tilted toward the lowest paid. The primary losers included landlords and other rentiers, as well as overseas investors, who saw the value of their assets wafted away like morning dew. In 1920, Walter Rathenau, a future finance minister who was chief executive of Germany’s largest electrical trust, openly extolled the power of inflation to increase exports and maintain employment. In fact, as the German financial press duly noted, the headlong depreciation of the Reichsmark against the dollar and pound was financially equivalent to a large interest-free capital infusion. By mid-1922, however, investors had taken fright, and the inflation had become destabilizing. Mounting civil disorder culminated in a wave of assassinations, including the murder of Rathenau in 1922. The Ruhr invasion the next year triggered a panicked flight from German debt and many creditors lost all of their stakes.15

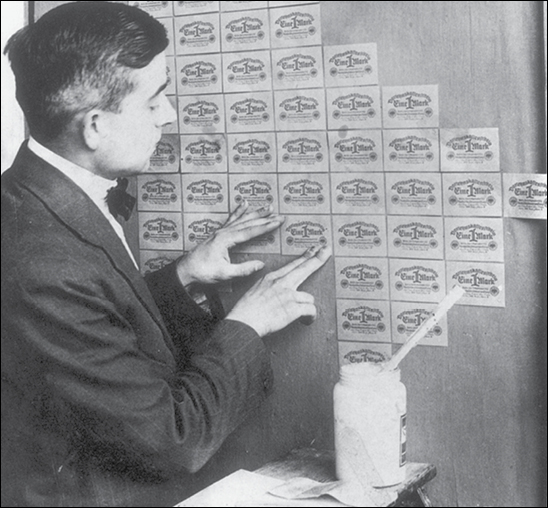

A man wallpapers his apartment with German Reichsmarks. They were made from high-quality paper and the hyperinflation made them much cheaper than ordinary wallpaper.

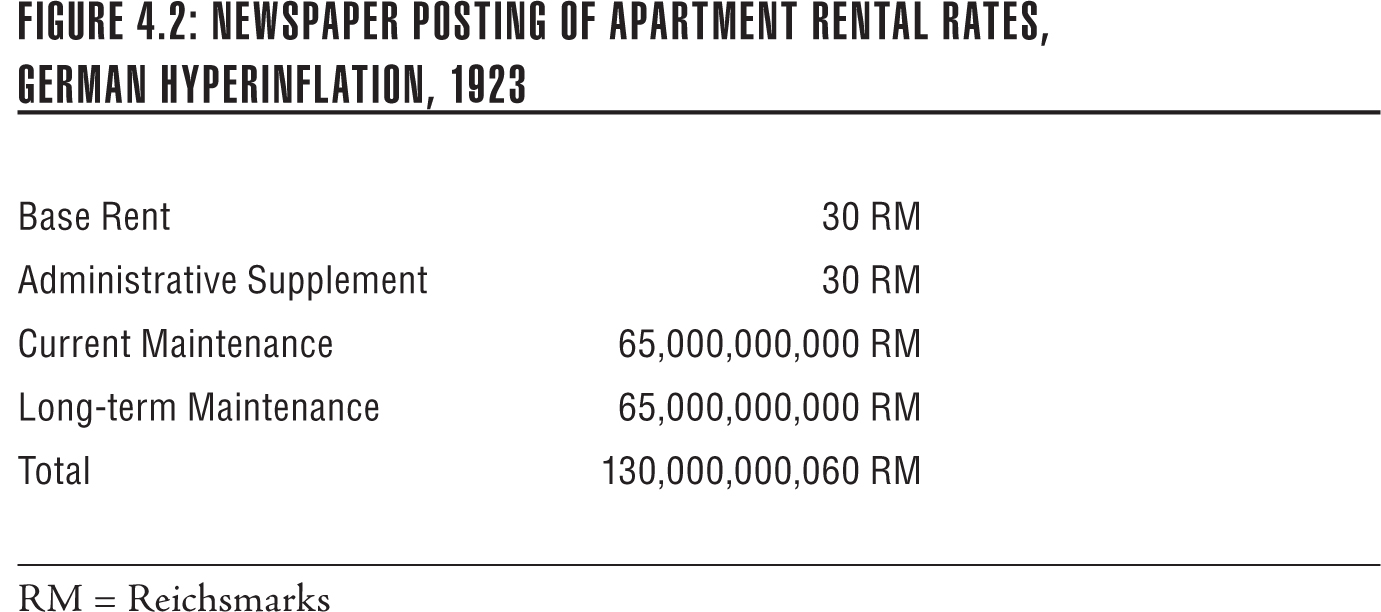

Long-standing financial practices contributed to the hallucinatory character of the Weimar inflation. Many taxes, especially for the wealthy, were assessed long before they were due, so the longer taxpayers waited, the less their payments were worth, automatically ratcheting up the budget shortfalls. Crazy price misalignments resulted from pervasive price controls on food, rents, and many other basic items. The country tipped into hyperinflation in mid-1922, up by 1,000 percent. By 1923, the increases were exponential: in August 1923, an American dollar bought 630,000 marks; in November, it bought 630 billion marks, a millionfold inflation. The most impecunious Americans could live like byzantine potentates. The writer Matthew Josephson enjoyed a palatial apartment, with a full complement of servants, and every amenity at his beckoning. It cost a Texan $100 to hire the entire Berlin Philharmonic for an evening. At the same time ordinary Germans had been reduced to barter. Some sense of the dislocations can be captured by newspaper inflation guides. The example in Figure 4.2 applies to apartment rents, which were generally under rent control. Readers were advised to check frequently for updates.16

As inflation spiraled toward infinity, it was the German industrialists who finally blinked. Foreign finance had dried up, and riots and other disturbances were spreading through the country. Their first concession was to accede to the French terms in the Ruhr. A new Conservative government, led initially by Gustav Stresemann, an economist and experienced politician and lobbyist, took power on the express condition that he could rule by decree. Within a couple of months he had restored calm and set about fixing the currency. His chosen instrument was Hjalmar Schacht, a brilliant, audacious, and wealthy banker, whose talents were compromised by his overweening ego and tin ear for ethical issues.17

The appropriate job for Schacht would have been the presidency of the Reichsbank, but that appointment was not within the government’s power, and the current occupant, a gentlemanly civil servant, refused to step down. Instead, Schacht was designated the “commissioner of currency,” charged with implementing an idea of Stresemann’s of a scrip or faux currency, called a “Rentenmark,” collateralized by German land. On the face of it, that was absurd, if only because a useful currency needed to be collateralized by a highly liquid and easily transferable asset. Schacht was doubtful, but agreed to give it a try. The Rentenmark was duly created as a legal tender, subject to a tight ceiling on supply, and it was announced that the government would be willing to exchange Rentenmarks for paper Reichsmarks. Setting the conversion price was left to Schacht, who turned the occasion into a powerful symbol of reform. He waited until the mark fell to 4.2 trillion to the dollar, and then set the price of a Rentenmark at 1 trillion Reichsmarks—4.2 Rentenmarks therefore equaled $1, just like the old gold marks. As luck would have it, on the very evening that Schacht fixed the Rentenmark conversion price, the civil servant who had blocked his ascendance to the presidency of the Reichsbank dropped dead, finally clearing the way for Schact’s appointment.18

Within a few weeks, people were lining up to trade in their paper currency for the new Rentenmarks, stores reopened, long-hoarded goods were back on shelves, commerce returned almost to normal. As Schacht mopped up the sea of paper currency, Stresemann steadily whittled down the Reich’s excessive social and reconstruction spending. As far as purely intra-German transactions were concerned, the economy started to tick along quite nicely, but the sleight of hand did little for Germany’s external credit. Foreign lenders had been badly burned by Germany’s adventures in currency despoliation, and refused any transactions not immediately settled in gold. Since Germany had very little gold, it could not make a lasting recovery without substantial gold credits, which could only come from the United States.19