VIII. GERMANY UNRAVELS

VIII. GERMANY UNRAVELS

For the first year or so on the Dawes Plan, the German economy revived considerably on its new diet of the Dawes loans. But it did not take long for the underlying contradictions in the Dawes arrangements to become evident. When France paid its reparations to Prussia after the 1870–1871 war, they paid for them with export surpluses that they earned by repressing national consumption and restricting imports, which worked real hardship on the populace. Germany, by contrast, paid its reparations out of the new foreign loans. Predominately American and British loan proceeds were paid to the Reichsbank, credited to the reparations account, and paid out to primarily to France, Belgium, and Great Britain. That worked fine in the short term—indeed, the Dawes plan explicitly described the loans as a stopgap until the German economy recovered to the point where reparations could be paid from national income.

The German leadership, Stresemann, Schacht, and the economics minister Julius Curtius, were well aware of their position. While they didn’t want to pay reparations, they didn’t mind the Allies paying reparations to each other. The problem, especially for Schacht, was that Germany was accreting large, private, foreign debts that would have to be paid in gold marks. Default could have serious consequences, since the Dawes protocols gave the reparations committee extraordinary enforcement powers, such as seizing tax collections. The original German argument against reparations was the nation’s postwar poverty. But there was a catch-22 in that argument. If Germany did repress growth to prove their incapacity to pay, their trade account would swing into the black as their imports fell, and the Allies would have the right to claim the German export surpluses as reparation payments.77

Schacht had nightmares besides the reparations conundrum. All the foreign money flowing into Germany looked like an engine of inflation. The smoothness of the initial Dawes loan placements had acted like a AAA bond rating, and brought funds, both long and short, flooding into the country. Part of the attraction was the very high Schachtian discount rates. (The discount rate was lowered to 9 percent in 1925.) Industry was clamoring against the financial stringency, the government budgets were running substantial surpluses, and the economy actually contracted through most of 1925 and 1926.78

The combination of repressive German bank rates and floods of foreign-sourced liquidity sloshing around the banking system cost Schacht control of the money supply. By early 1927, he was forced to drop discount rates down to just 5 percent. But he was determined to force rates back up, which he proceeded to do with his characteristic mix of cleverness and ham-handedness. In December of 1926, he had prevailed upon the government to end the exemption from capital taxes for foreign bond purchasers, which stopped the foreign cash inflows in their tracks. Then he turned to the stock market, which he regarded an engine of speculation. In what has been called an “excessively brusque action,” he forced sharp reductions in bank margin lending, under threat of loss of rediscount privileges. The banks complied, but the Berlin banks made a dramatic joint announcement that precipitated a severe market crash. The consequent flight of gold and foreign exchange from Germany forced a rise in the German discount rate to such an extent that Schacht had to acquiesce in a restoration of the capital tax exemption for foreign bond purchasers. (Subsequent research makes a strong case that there was no bubble in German stocks.)

Then, in February of 1927, Germany floated an enormous bond issue, possibly the biggest German bond issue ever to that point, with distribution limited to Germans. The bond issue was the brainchild of Peter Reinhold, the finance minister. The target principal amount was 500 million gold RMs, with 300 million distributed by a syndicate of eighty German banks and 200 subscribed for by state companies. The loan drew a great deal of criticism, both from Schacht, who feared that such a huge amount of money in the hands of the government could only be wasted, and even more from Parker Gilbert, the reparations agent. In a report for the half-year ending in June 1927, Gilbert showed the booking of the 500 million RMs, while noting that only 373 million had been realized from the flotation (German budget practices in this period were to book all planned receipts, with later fine-print deductions of shortfalls).*79

As much as anyone, Gilbert forced the reopening of the Dawes plan because of the slippage in the German budget performance. In 1927, for instance, an extremely generous unemployment benefits program sailed through the National Assembly without any funding provision. Gilbert warned that the reparations agenda would never be cleared up unless Germany started to “act to save itself, instead of looking to foreign loans and credits as a means of avoiding the disagreeable job of internal reform.” Owen Young was drafted to chair a Dawes-like committee to develop a proposal. Mellon and the Coolidge administration blessed the undertaking, although stipulating that the American government had no official involvement with it.80

The Young panel’s sessions were bumpy. Although both the Germans and the Allies had agreed in principle to establish some smaller, but significant, reparations schedules, it took months of wary circling before anyone produced hard numbers. The Germans seem to have convinced themselves that the Allies had realized what an obstacle to recovery the reparations had become, while the Allied representatives were willing to entertain some reductions in return for tightening the screws on German performance. It did not help that a Labour government took office in Great Britain and Chamberlain was replaced by Philip Snowden. He was an unusually irascible and contentious man, and tied up the conference for months straining pettily to capture more payments for Great Britain. The German side, unfortunately, was represented by Schacht, who was as disruptive as Snowden. When the final deal was cut, he refused to sign it, indulging in histrionic displays until he was ordered by Stresemann, in effect, to shut up and sign it before the Reich collapsed.

The Germans had reasons to be disappointed with the revised reparations schedule, since it was only about a fifth smaller than the Dawes payments. Stresemann wearily assured his colleagues that the Reich would collapse financially without new money, and the “Young plan,” as it was called, would be reopened just as the Dawes plan was. The reparations agent was replaced with a new organization, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), to process and distribute the payments. The BIS still exists today, because as Young and others perceived, and as its name implies, it became a useful clearing house for netting and settling international payments.* Once the deal was agreed in January 1930, the bankers floated a $300 million loan, two-thirds of which went to reparation creditors, with the rest to German budget relief. It was to be the last reparation payment. Nobody mentioned that the so-called “final” reparation schedule was well within the boundaries of German affordability posited by Keynes in his The Economic Consequences of the Peace.81

For all the real progress, there was a still sour edge to the winding up of the Locarno process. It had taken far too long, too much had been left undone, promises made in apparent good faith had not been kept. Again and again, negotiators who thought they had political clearance for their commitments were reversed because of power shifts at home. Snowden’s last-minute antics embittered the French and the Belgians. The death of Stresemann shortly after the final agreements had been signed removed perhaps the central figure in the process, one of the last of the moderate Germans.

The years from 1924 to 1929 have been called the “golden age” of Weimar. But few people seemed to realize how precarious the German financial position had become. The country seemed prosperous, with real GNP growth of 5.6 percent from 1925–1929. But in retrospect the signs of a slump were visible as early as mid-1927, when the country began to run an export surplus. It wasn’t because exports had risen; rather, it was because imports were falling faster than exports, suggesting an important weakening of spending, especially in investment and government spending. The economic historian and Weimar specialist Theo Balderston makes a strong case that the fatal fault lines lay in the German financial system. There was an extensive array of yawning pitfalls: investors were nervous about the rising reparations under the Young Plan; there had been sharp unfunded spending increases in the Reichstag, suggesting a loss of discipline; the failed 1927 bond issue highlighted the enduring incapacities of German banking; and the right-wing shift in German politics possibly presaged an early repudiation of the entire post-Versailles treaty apparatus. All of those worries were dwarfed by the bedrock flaws in the German banking system, which had still not been fully recapitalized after the Great Inflation. About 40 percent of their deposits were short-term and foreign-owned and could disappear in an eye-blink.82

Gilbert’s final report released in 1930 was caustic:

First and foremost, there has been no effective recognition of the principle that the Government must live within its income. Revenues have been ample… [and] would have been adequate to meet all legitimate requirements of the Reich, and even to provide a reasonable margin of safety, if only a firm financial policy had been pursued. For the past four years, however, the Government has always spent more than it received and at times, especially during 1929–30, it has made commitments to spend even more than it can borrow.83

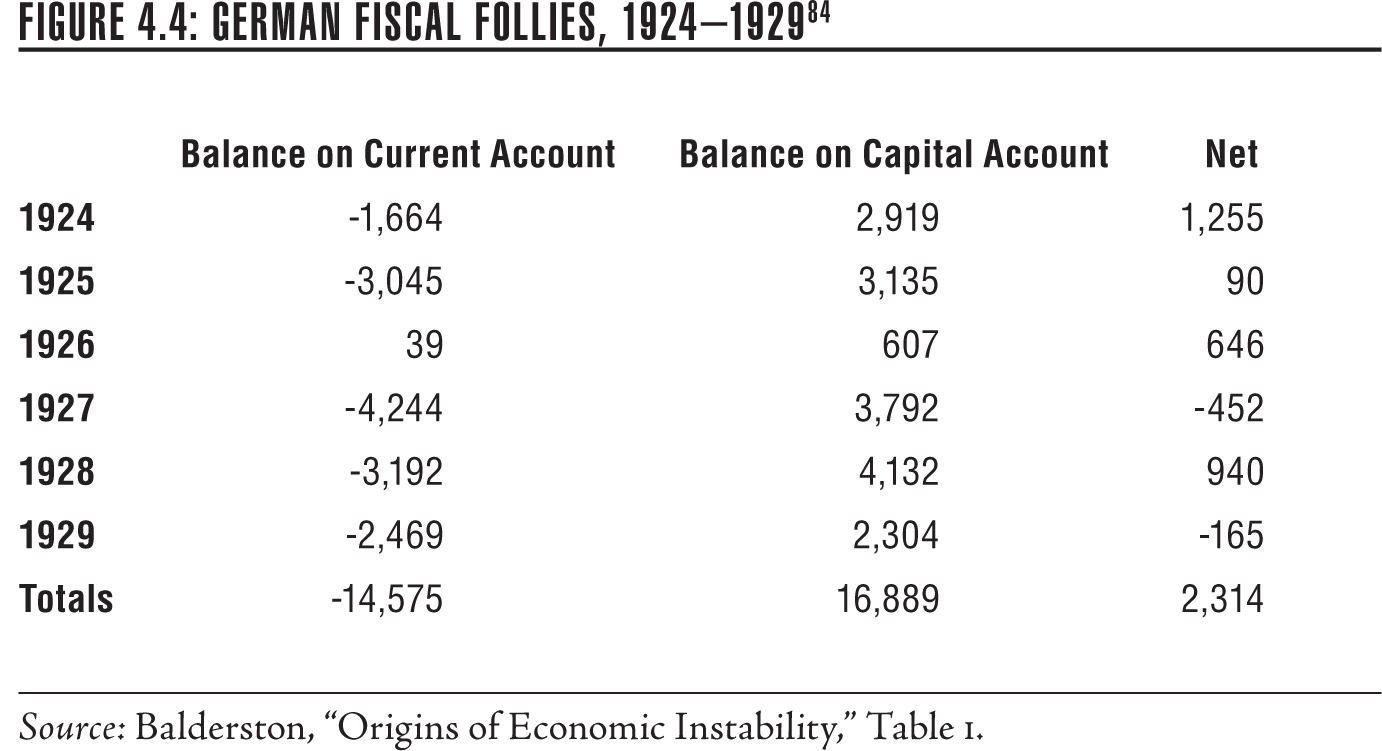

It wasn’t a pretty picture. The budget was out of control and public debt was rising rapidly. During the 1929–1930 fiscal year, debt increased by 16 percent, two-thirds of it short-term floating debt, most of it callable. German authorities later complained that their problems didn’t commence until 1928, when the American stock market sucked up American liquidity, cutting off its primary funding source. That wasn’t true (see Figure 4.4). Germany was running big trade deficits (the current account), while at the same time receiving very large, often unsecured, capital infusions from starry-eyed investors (the capital, or borrowing account). The total of reparations paid over the entire period of the Dawes plan was less than the proceeds from international loans. In other words, the Germans paid the reparations by borrowing from the war’s victors, and rubbed it in by defaulting on the loans.