III. CREATING THE “NEW DEAL”

III. CREATING THE “NEW DEAL”

No one ever accused the Roosevelt first-term program of consistency, nor would he or any of his advisers have made such a claim. In a commencement speech at Oglethorpe University, in the spring of 1932, Roosevelt told the graduates:

The country needs and, unless I mistake its temper, the country demands bold, persistent experimentation. It is common sense to take a method and try it: If it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something. The millions who are in want will not stand by silently forever while the things to satisfy their needs are within easy reach.30

The landslide election victory essentially gave him a free hand, a writ to reshape the government and its mission as he chose. To be sure, the troglodyte wing of the Republican party detested “that man in the White House,” but they had been discredited by the market crash and the Depression. Although the South was solidly Democratic, its congressional bloc eventually came to oppose many of the administration’s initiatives that appeared to empower black Americans—and generally got their way. Roosevelt, however, drew considerable benefit from the fact that his most serious early political opposition came from the left. Whenever recalcitrant congressmen deplored the radicalism of his program, he could paint a dire picture of what the real radicals would do if the New Deal foundered.

Mainstream Roosevelt supporters comprised an unwieldy mix of progressive intellectuals, blue-collar workers, small farmers, and social activists of all kinds, many of whom, like Harry Bridges, the great union organizer, were later targeted by Joe McCarthy’s 1950s Communist hunters. There were a few charismatic individuals, however, who grasped the inherent power of the new mass media at least as well as Roosevelt did. They were supportive of the administration in the early days, but soon morphed into an informal opposition, for reasons both of principle and pique.

Charles Coughlin was the “radio priest,” who turned a weekly broadcast from a church in Detroit into a national phenomenon. In the year before Roosevelt took office, Coughlin called for doubling the price of gold to expand the currency and fuel greater spending. He vaulted into national prominence as a witness in the trial of executives of two big Detroit banks whose imminent failure had helped trigger the nationwide wave of bank closings. Although Coughlin was an incurable sensationalizer, the executives’ crass self-enrichment justified some extremism. (A bank examiner called their behavior “putrid.”) By the end of the year, Coughlin was getting 10,000 letters a day—to the point where the postal service gave him his own post office. A flood of small donations financed a media empire, with national radio links, a newsletter, and books. A first edition of his broadcasts quickly sold a million copies. During the first few years of his prominence, Coughlin was warm in his praises of the president, and Roosevelt paid him the honor of a private hour-long meeting. But Coughlin grew disappointed with Roosevelt’s progress, and even more with the lack of attention he received from the White House. Within a few years, he had become a dangerous opponent with a marvelous personal megaphone.31

Then there was the “kingfish,” Louisiana’s redoubtable Huey Long. Long’s DNA was deeply entwined with that of his home state, and its political machinery worked like an extension of his brain. He was a demagogue, a shrewd mix of flamboyant buffoonery and cold calculation in service of his own ascendancy. But Long also delivered for the common man. In his first term as governor, he started an impressive highway building program, funded textbooks for all schools in the state, and passed a more progressive tax code. But a proposal to tax every barrel of oil refined in the state aroused the wrath of Standard Oil, the traditional muscle in Baton Rouge, the state’s capital. An impeachment movement was quickly organized, but Long, exercising his entire demagogic kit bag, carried all before him, cementing his dominance in Louisiana. When term limits prevented him from retaining the governorship in 1932, he engineered both his election to the US Senate and his replacement in Baton Rouge by a loyal retainer. And a few years later, he finally got his oil tax.32

Long was materially helpful to Roosevelt at the 1932 Democratic convention, but Jim Farley, Roosevelt’s political guru, restricted his involvement in the campaign, only to be startled by the pro-Roosevelt voting shifts that regularly followed a Long speaking appearance. For a while in 1933, Long’s heavy drinking and vulgar clowning eroded his support at home, but he straightened up, dried out, and crushed any budding resistance. He also began to build a Coughlin-style media empire, and in 1934, in a brilliant stroke of branding, began his Share Our Wealth program—confiscatory taxes to ensure that no one retained more than $1 million of net earnings, with the proceeds going to a modest guaranteed nest egg for each child and minimum federal income support for the needy. Long was a diligent organizer who soon had in place a formidable system of local Share Our Wealth Clubs, which to Farley’s suspicious eye looked like a serious grassroots political organization.33 Coughlin and Long loosely coordinated with each other, and in 1935, they forged a similarly loose alliance with Francis Townsend, a sixty-six-year-old California doctor who was pushing a plan to provide every person over sixty years of age a monthly federal pension of $150, the equivalent of about $2,600 today. When a hazy array of radical farmer and labor groups appeared to coalesce in support of a Coughlin-Long-Townsend political party, the White House became genuinely alarmed at its potential to destabilize the 1936 election.34

From left to right: Huey Long, Fr. Charles Coughlin, and Francis Townsend, for a short time in Roosevelt’s first term became forceful advocates for strongly redistributionist government policy. Over time many of the policies they called for have become part of the American safety net.

Nothing of the sort happened. Long was assassinated in September 1935, shot in the Louisiana State House by the son-in-law of a judge whom he had squeezed out of office. (Long may well have survived in the hands of even moderately competent surgeons.) Without his presence, the network of Share Our Wealth clubs dissolved. As for Coughlin, he became increasingly extreme and, especially after 1938, grossly anti-Semitic. He and Townsend, plus a core group of their followers, organized the Union Party to run a nearly unknown North Dakota congressman, William Lemke, for president in 1936—who was utterly swept away in a historic Roosevelt electoral tidal wave.

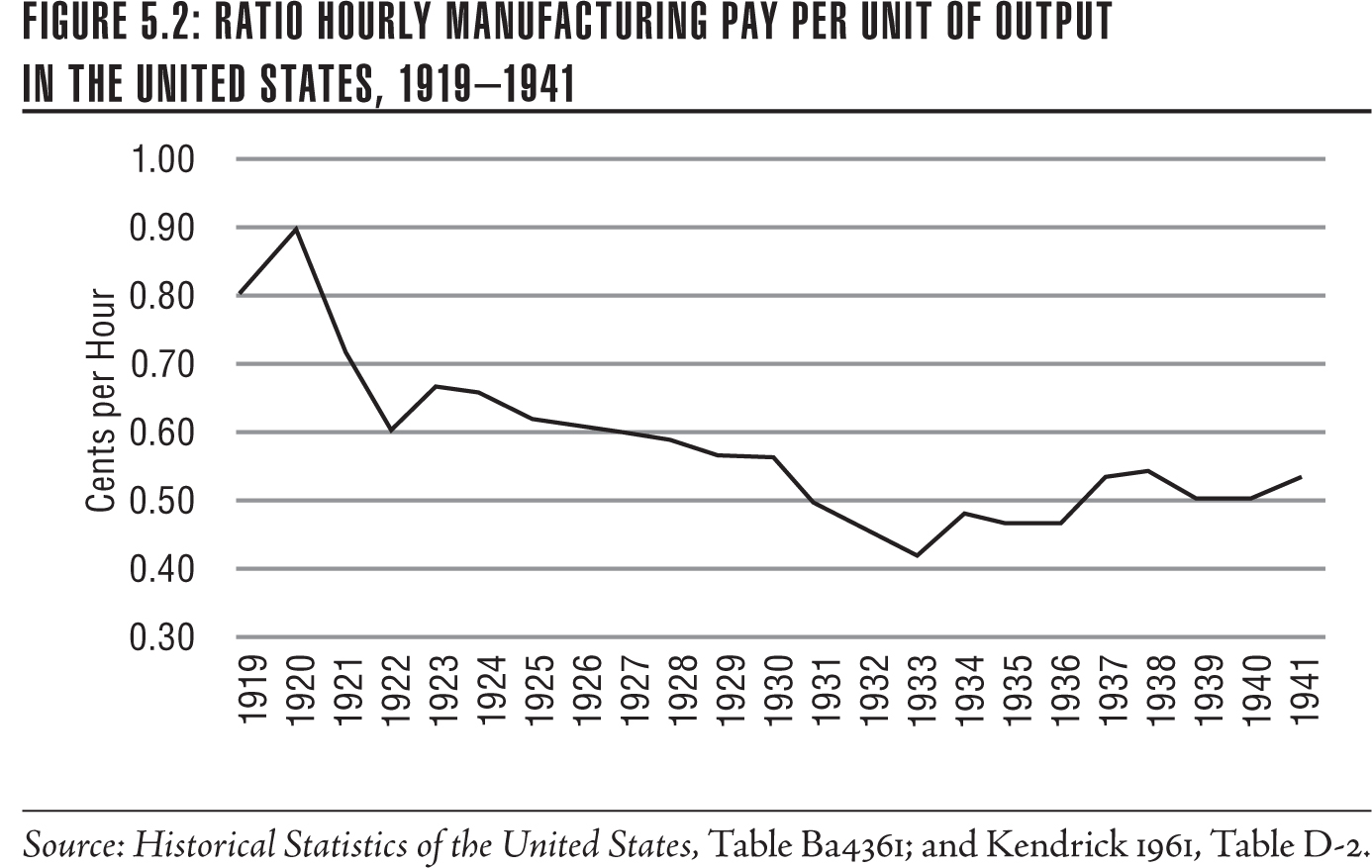

Long, Coughlin, and Townsend were tapping into a rich vein of discontent. Workers were treated badly in the 1920s, even leaving aside the absence of job security, abusive shop foremen, long hours, and lack of overtime. Factory productivity growth was extraordinary, but as Figure 5.2 shows, workers got very little of it. The lack of income growth in worker households was made up by working longer hours and by borrowing, as consumer credit became steadily more available through the decade.

Nor by any means were the programs the three men espoused complete nonsense. Coughlin’s gold price target of $41.34 an ounce was the same as George Warren’s, and wasn’t that far from Roosevelt’s choice of $35 an ounce. Townsend’s pension plan, of course, adumbrated Social Security. Long’s Share Our Wealth plan was never a serious option, but the American tax code turned decidedly confiscatory in wartime, just as it did in World War I. This time, however, when the war ended, the tax code stayed confiscatory (a 75–90 percent top bracket) well into the 1970s. That paid for countless postwar infrastructure and human resource investments. The all-important GI Bill of Rights financed college or other post–high school training for 7.8 million returning veterans, or nearly half of all servicemen and women. Veteran home mortgage guarantees practically created the suburbs.

Much of the spending, directly or indirectly, came out of the pockets of the rich. In 1928, the top 1 percent of taxpayers received about 24 percent of taxable income, or about the same share as they have absorbed through most of the 2000s. But the Roosevelt tax skew toward the upper bracket payers stayed in place well into the 1970s, and through all that time, the share of taxable income flowing to the top 1 percent of earners averaged just 10 percent, and the annual growth in taxable income was roughly the same across all income quintiles.* CEOs were wealthy men with nice houses in normal neighborhoods, not Sultan-of-Brunei-scale royalty with globe-girdling servanted estates. “Inequality” was not a political catchphrase, because most people felt that they were steadily improving their lot. That, too, was part of the Roosevelt legacy.35