IV. THE NEW DEAL IN OVERVIEW

IV. THE NEW DEAL IN OVERVIEW

The New Deal programs were a pastiche of income transfers, price and market interventions, and permanent regulatory initiatives. The first programs to get into operation were focused on creating jobs, like the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), which included welfare payments for the unemployable destitute. The Civilian Works Administration (CWA) was a four-month program in the winter of 1933 that employed over four million people at competitive pay rates. Additional income transfers, like unemployment insurance, public assistance programs, and Social Security, took longer to phase in since they often required state-managed operating structures or, as in the case of Social Security, an entire new federal bureaucracy.

A second thread encompassed programs to change market outcomes in pursuit of specific price, wage, or other policy objectives—the agricultural bill, with its programs to reduce output in order to maintain prices, and the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), to accomplish similar objectives in industry, are the primary examples. Farmers got their price supports, and industrial workers got fair labor standards protection, a federal minimum wage, and greatly enhanced bargaining rights. Finally, there were four new permanent regulatory bodies, following the model of the Interstate Commerce Commission, the most important of which was the new Securities Exchange Commission.36

Given the blur of activity and the sheer variety of the initiatives, scholars have long clashed over the benefits, if any, the country reaped from the exercise. Over the past couple of decades, however, scholars have been amassing detailed data on the major programs, and find that they had real, if mixed, results. But before we look into the details, there are two important general points.

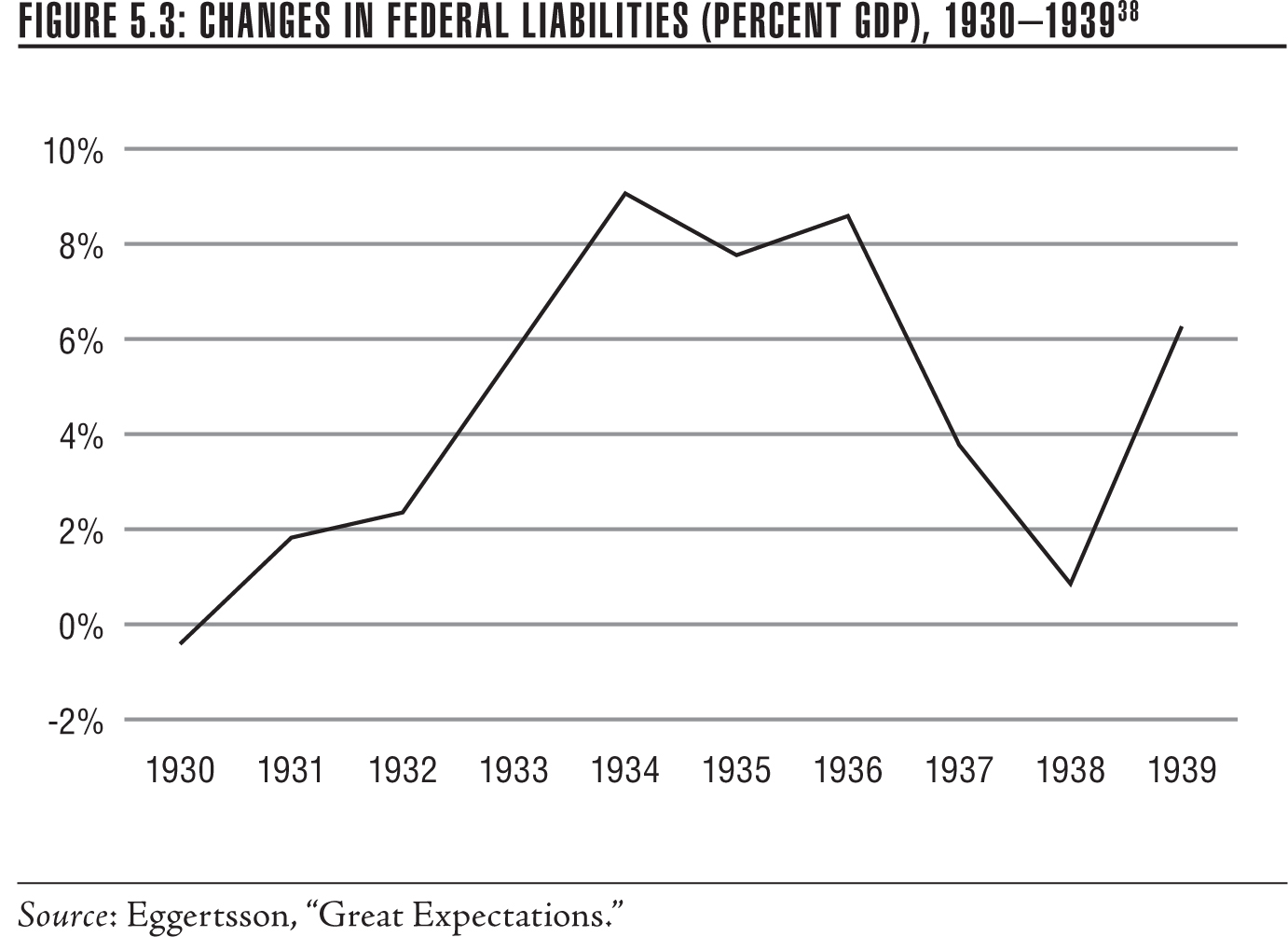

There is a widely accepted misconception that Keynesian fiscal policy—running deliberate government deficits to add to spending power—was not a factor in the recovery. As an early scholar put it, “fiscal policy… seems to have been an unsuccessful recovery device in the thirties—not because it did not work, but because it was not tried.” While it may not have been the main factor, it was not trivial. Figure 5.3 shows the year-to-year increase in federal liabilities, both budget deficits and off–balance sheet borrowings like the RFC’s from 1930 to 1939. By the standards of the day, they were quite large. Most such outlays were subsequently repaid—as was most of the “bailout” spending during the recent Great Recession. It’s the stimulative effect at a time of economic crisis that matters. Hoover also engaged in off-budget stimulus spending after 1930, but at a much lower level. For Hoover, moreover, the deficits were unintentional—he did his best to fund them with tax increases, but could never catch up to the fall in GDP.37

Secondly, there is a striking vein of research that suggests that the main factor in the recovery was Roosevelt himself—and it’s not nearly as far-fetched as it sounds. It has long been a puzzlement that the economy picked up sharply in the month that Roosevelt finally assumed the presidency. There was no obvious reason for it—no sudden increase in the money supply, no fall in real wages that might explain a turnaround. The traditional explanation was that at some point, a collapsing economy will revert to its mean. As Kindleberger put it, “the fact that gross investment has a limit of zero is useful in explaining that the depression had to end. At some point gross investment turns up again and the accelerator principle comes back into its own.”39

But that explanation doesn’t comport with the facts. Manufacturing inventories were still very high relative to sales in 1933, so investment was far from hitting the “limit of zero.” Nor did Roosevelt’s gold devaluation entirely explain the upturn, since it wasn’t fully effective until January 1934. The New Deal legislative program was passed with record speed, and included major new policy experiments, like the AAA and the NIRA, but it would be a while before they had much effect.

Peter Temin and Barrie Wigmore, in a 1990 paper, proposed a “policy regime change” as the explanation, working its magic through a change in expectations. Hoover relied mostly on jaw-boning in the early days of the collapse, especially asking industry to maintain wages. His most promising initiative was the RFC, although it was trammeled with restrictions that limited its effectiveness. As the crisis worsened, however, he took to blaming the Europeans, and adopted a strong deflationist policy—balancing the budget, protecting the gold parity, imposing steep tax increases, and grimly proclaiming that the government could do little except try to squeeze all the excesses out of the economy.

Temin and Wigmore do not argue that the public understood the details of the new administration’s policies, but only that they grasped that Roosevelt’s approach would be completely different. Roosevelt bided his time during the long post-election interlude, not attacking Hoover, but refusing to ally himself with the Hoover agenda. In his first weeks in office, he openly trumpeted his reflationist agenda with the bank holiday, the floating of the dollar, the suspension of gold exports, and his “bombshell” message to the Monetary and Economic Conference. The reaction of conservative media underscored the radical nature of the changes. The Commercial and Financial Chronicle called it “a step backward toward the darkness of the Middle Ages,” while the head of the Chase Bank wailed that the devaluation was “an act of economic destruction of fearful magnitude.” The wave of new legislation, large appropriations for the AAA, the open embrace of deficit spending, and a new, and more cooperative, chairman of the Federal Reserve who promptly eased credit were all part of the show. And it helped that some financial luminaries, including Jack Morgan, supported the president’s policies. The stock market was gleeful. Industrial stocks doubled in the first four months after the inauguration, and the production of investment goods more than doubled by the fall of 1933.40 Such developments, all in all, seemed dramatic confirmation of the Roosevelt campaign song, the Tin Pan Alley favorite, “Happy Days Are Here Again.”

The economist Gauti Eggertsson has created a general equilibrium model* for both the deflationist “Hoover policy regime” and its replacement Roosevelt regime. Economic modeling of this sort is still a work in progress—if only because results are often suspiciously consistent with the political dispositions of the modeler. If nothing else, however, Eggertsson’s work provides details for a plausible path to the Temin and Wigmore thesis. A paper by the economist Christina D. Romer rounds out the picture by identifying the fuel that extended the hyperfast recovery after the Roosevelt reflation—the huge flood of gold into the United States. A key to the effectiveness of the gold influx is that it went to the Treasury, not to the Federal Reserve, which based on past behavior would have sterilized it. Gold is high-powered money, and the monetary base swelled by about 10 percent a year in 1934–1937. It is probably not a coincidence that the economy grew by nearly the same rate through that period.41