IX. THE UNEMPLOYMENT CONUNDRUM

IX. THE UNEMPLOYMENT CONUNDRUM

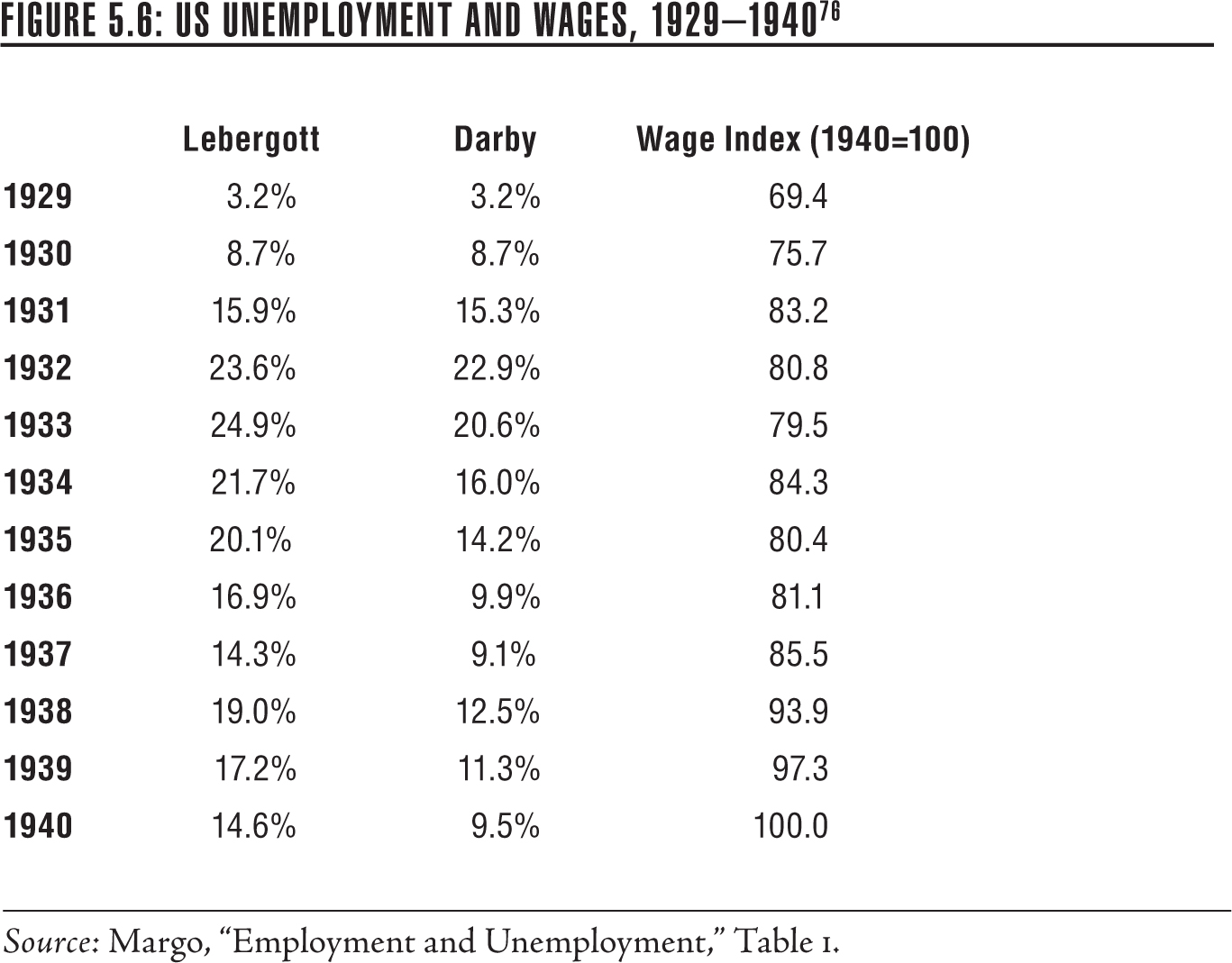

Nineteen-twenty-nine was a boom year, with durable goods, especially, running ahead of their markets. It is also the first year for which the Department of Commerce later produced official GDP figures, so it is the benchmark for measuring the downturn. The steep descent of real GDP ended in 1933, with a four-year real drop of more than a quarter. The economy recovered to its real 1929 level in the three years from 1933 through 1936—a 36 percent gain from the 1933 low point. Per capita GDP caught up to 1929’s level in 1939, and by 1940, per capita real GDP was 10 percent higher than in 1929. After an extreme drop, in other words, the GDP numbers suggest a brisk recovery. But the long unemployment lines belied those data.75

The difference between the Lebergott and Darby unemployment data is simply that Darby counts workers on government relief programs as employed, while Lebergott counts them as unemployed, which was the Census Bureau practice. Unemployment figures for this period, in any case, have large margins of uncertainty. No government agency conducted surveys of the unemployed like the modern Current Population Survey does. Instead, unemployment was taken as the residual of two other databases—the labor force participation rate and the employment-to-population ratio. Very small variations in either of the two source databases may generate major differences in the residual. The data from this era are also likely to harbor major sampling errors—big companies were consistently oversampled, for instance—and definitions and counting conventions were still evolving.77

The primary conundrum, however, is the behavior of real wages. A hoary postulate of classical economics is that employment moves in the opposite direction from the real wage. If the real wage is higher than the market-clearing rate, employment will fall (and unemployment will rise) until wages adjust to balance demand and supply. If real wages are too low, conversely, job openings will go unfilled until employers adjust wages up.* So the puzzle of the 1930s is, with a reserve army of the unemployed equivalent to a quarter of the labor force, most of them with respectable recent work histories, why didn’t wages fall?78

The traditional answer, notably from Keynes, was “sticky wages.” That made intuitive sense in England, where the postwar Labour governments had won near-blanket union coverage in major industries with national bargaining protocols conducted by professionals on both sides. National bargaining by itself provided a pro-wage momentum, reinforcing the stated political objective of raising the income of the working classes.79

But the United States was not England. Unions had strong support within the Roosevelt administration, but most large employers were unalterably opposed to them, a position that commanded considerable sympathy among conservative Democrats, especially in the South. Unionism, however, had become a transcendent cause, with its own songs and folk heroes, much like the 1960s civil rights movement. After the demise of the NIRA, legal protections for workers were enshrined in the National Labor Relations and the Fair Labor Standards Acts.

But the panoply of new protections was not self-enforcing. It took several years to establish rules of decision, and progress was slowed by a host of hostile congressional investigations. Consider the epochal confrontations in the automobile industry, especially the multiyear effort by Walter Reuther’s United Auto Workers (UAW) to organize the Ford plants. The company resorted to hiring thugs to intimidate workers, and Reuther and his top aides absorbed a fearful beating at the Rouge River plant in 1937. The company’s lawyers fought a grim phrase-by-phrase battle against the new National Labor Board’s authority, and Ford even agreed with the old-line, and corrupt, American Federation of Labor (AFL) to sponsor a second auto workers’ union with company support. Reuther’s union finally prevailed in 1941 by huge margins, much to Ford’s chagrin. By the end of the war, the industrial unions were recognized in big plants throughout the country, and big companies were professionalizing their employee relations and bargaining functions. But the notion that in the 1930s, employers were greatly trammeled by a “sticky wage” tradition, does not comport with the facts.80

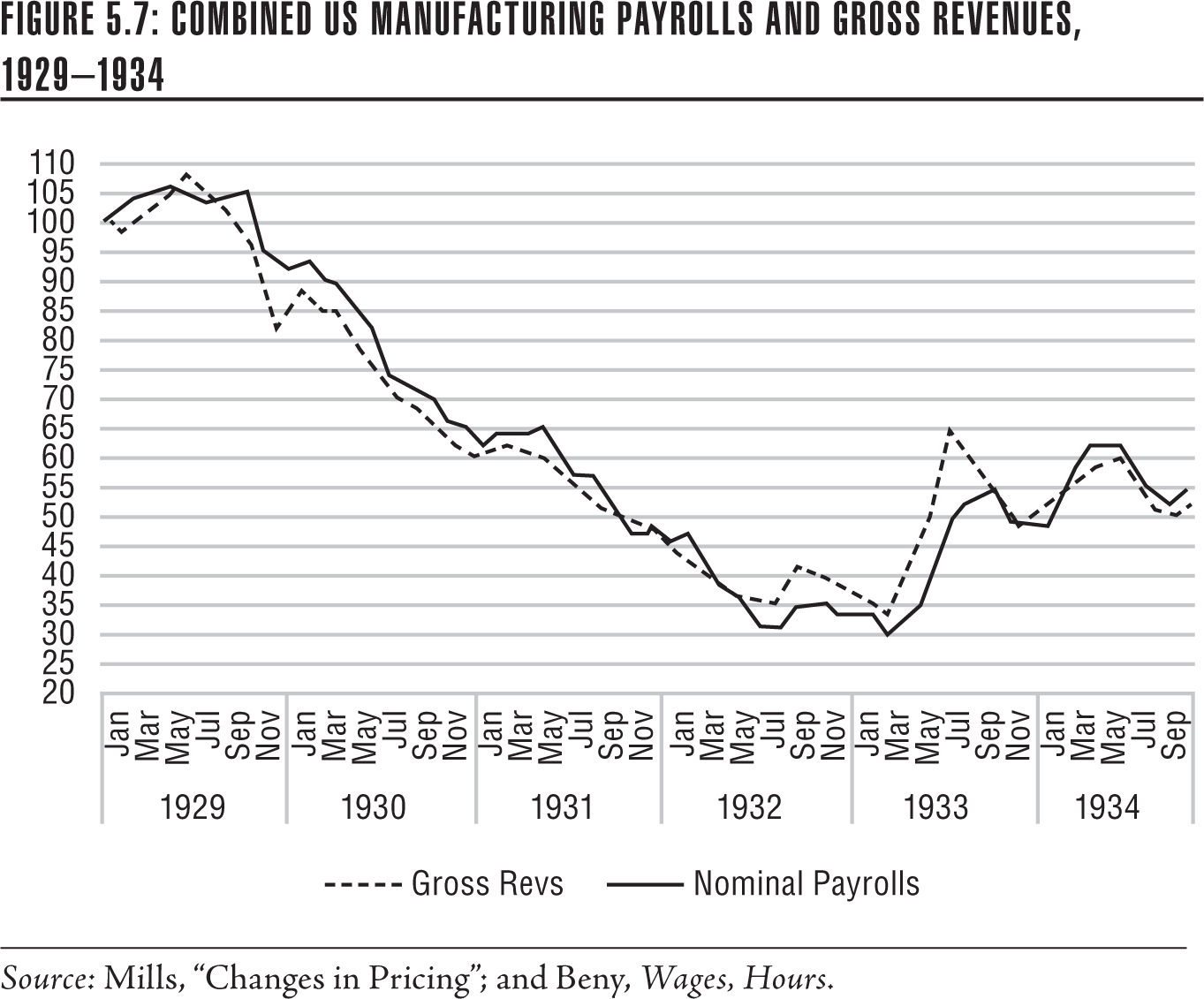

An early NBER effort, however, sheds light on how big employers managed their workforces during the Crash. Frederick C. Mills was a researcher engaged in the Kuznets GDP project. His specialty was prices, and he put together a data set of monthly manufacturing unit output and sales prices for the years 1929–1934. Multiplying sales and prices produces manufacturing gross revenues. Figure 5.7 combines those data with contemporaneous manufacturing payroll data collected by the National Industrial Conference Board (NICB), including nominal and real hourly and weekly wages, average worker hours employed, and the total payroll.81 I’ve adjusted the Mills data, however, to take into account a discrepancy between his data and that of the Census Bureau. Mills and the NBER use quoted prices rather than final prices in their pricing data bases. Mills points out the size of the discrepancy, which he attributes to depression-driven price-cutting, but also notes a number of other factors, like skimping on part quality, substituting less expensive models, and other factors. To be sure my numbers are conservative, however, I adjusted the data to assume that all of the discrepancy is from price-cutting.

Employers’ behavior seems quite rational. Most employers were optimistic in late 1929 and early 1930, and seem to have delayed drastic manning cuts. Once they changed their outlook in 1930, wages were tightly linked to the falling profile of revenues until late 1933, when the Roosevelt wage legislation came into play.* Businesses managed their payroll by cutting hours of those employed, cutting workforces, and cutting nominal wages, in that order. It’s not likely that they were trying to track real wages. This was, after all, a time when even the Federal Reserve ignored real interest rates. Instead they appear merely to be trying to keep their expenses within their available revenues.

There were practical limits that dictated the sequence of cuts. At the outset, it probably made sense to emphasize cuts in hours before employees, since shift times could be varied from day to day. But running a plant with many short-hour shifts could quickly become inefficient. And too-short shifts had their own problems: a report on the steel industry indicated that the 1932–1933 average steel worker earnings were below the “minimum health and decency” standard for a family of four. Finally, in complex industries, there would necessarily be essential operations that required a minimum of skilled men.

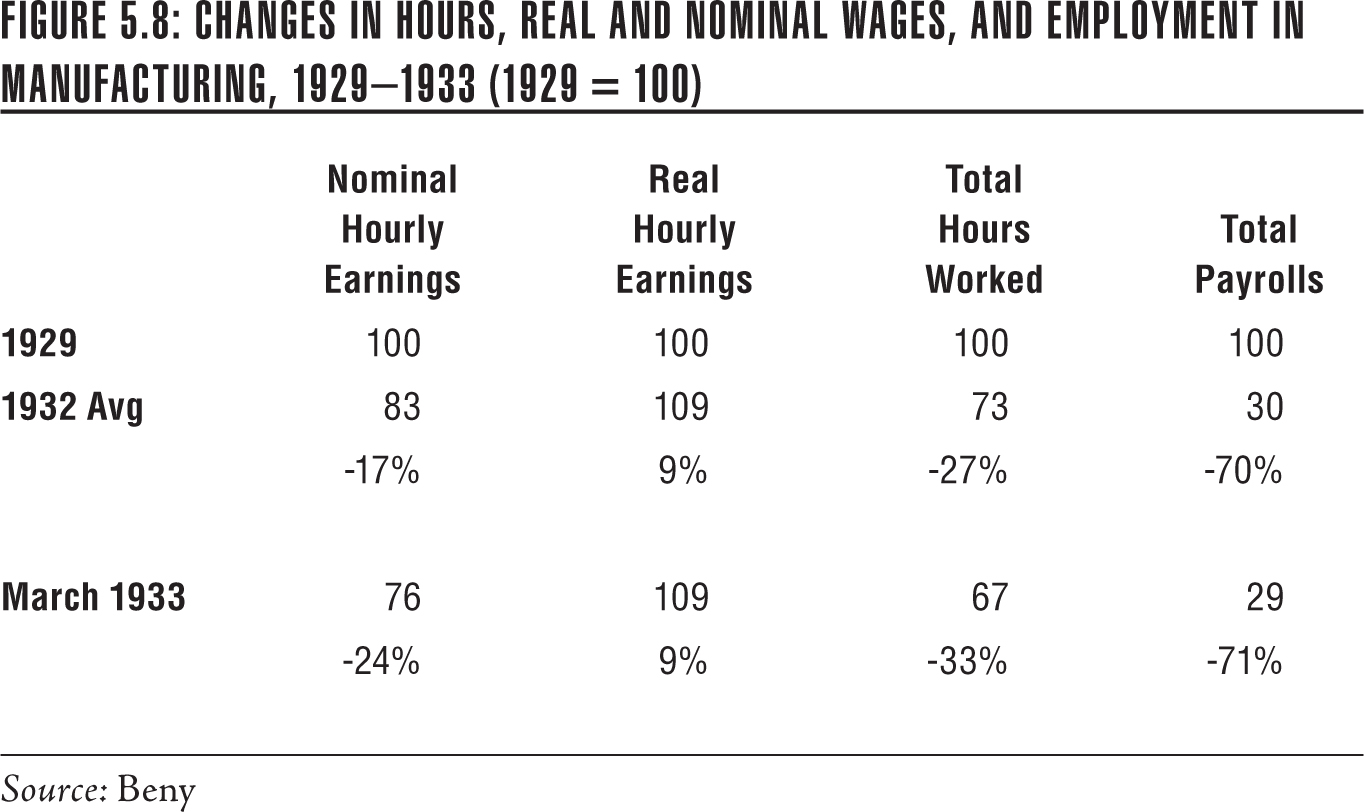

Figure 5.8 compares the 1929 averages for nominal and real hourly pay, hours worked, and total payrolls to the average for 1932, and to the nadir of this series, which came in March 1933. It also demonstrates the great advantage of staying employed during the Depression. Factory workers who kept their jobs through 1932 had an effective real wage 20 percent lower than in 1929, after accounting for the increased purchasing power of a dollar. Employers, of course, kept their books on a nominal basis, and the reductions in average actual pay and hours worked in 1932 would have reduced nominal payrolls to about 60 percent of the 1929 amount. Since payrolls were cut to only 30 percent of the 1929 level, manufacturers must have cut their work forces in half. In the big factory towns, like Detroit, there would have been little alternative employment, leaving family heads to the lean pickings of the dole or WPA projects.

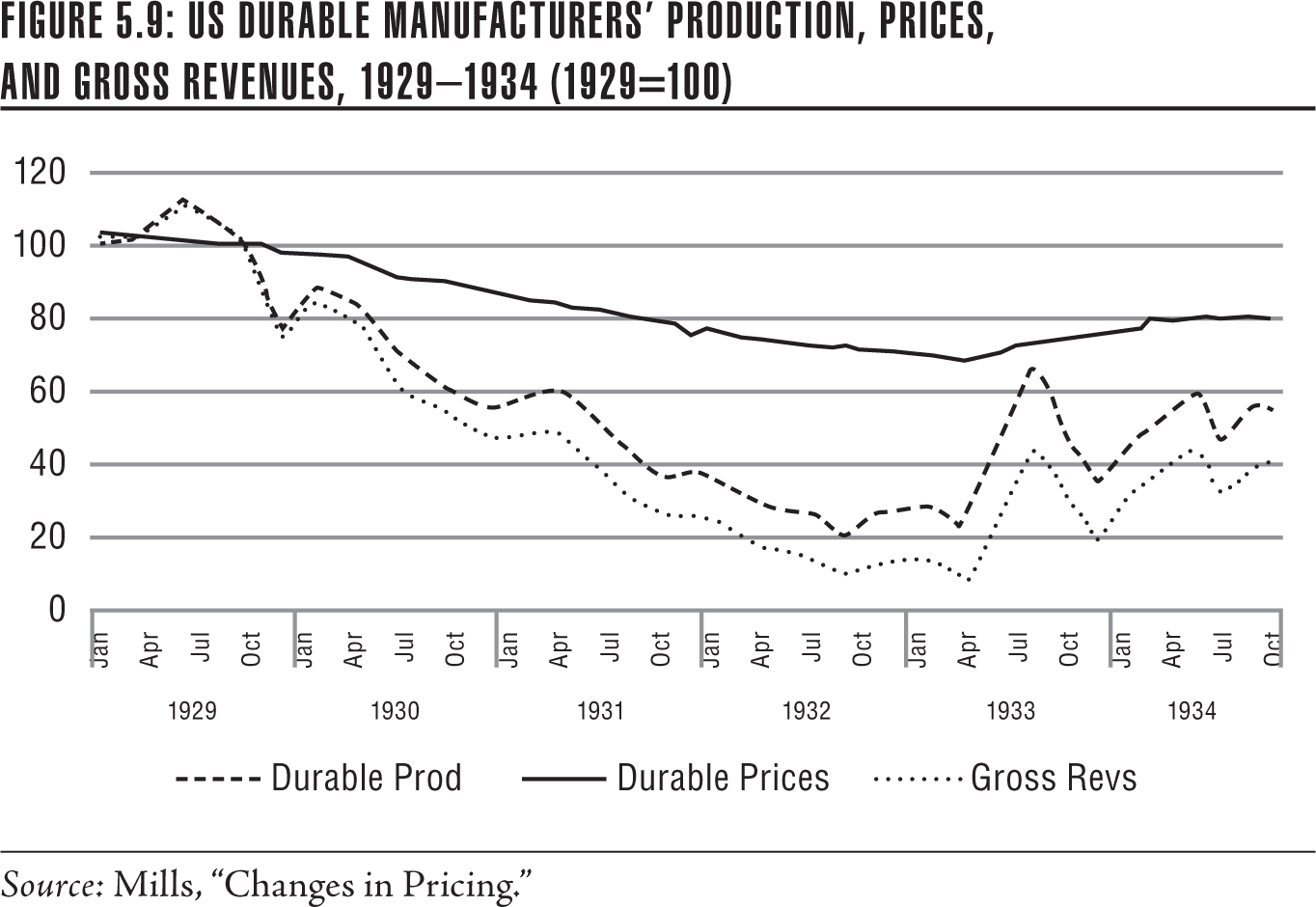

Interestingly, the Mills data also suggest that there was a strong “sticky price” phenomenon operating among the durable manufacturing sector during this period.82 (See Figure 5.9.)

There is anecdotal evidence supporting the existence of sticky prices. Time reported in October 1932 (note the date; it was already well into the third year of the Depression):

Prosperity, depression and a threatened investigation by the Government were unable to change the price of steel rails for a decade. Billets might go up (to $36 a ton in 1929) and billets might go down (to $26 last week), but the price of steel rails mysteriously remained at $43 a ton.

Last week Myron Charles Taylor, chairman of United States Steel Corp., invited a group of railroad presidents… to lunch with him in his company’s private dining room. He told them how concerned the steel industry was with the lack of orders from their industry, especially at the lack of rail orders. The rail-roadmen suggested that if the price of rails were a little lower they might be interested.

The very next week, all the steel companies reduced their rail price by $3 a ton, or 7 percent, producing, if not a flood of orders, at least a temporary bump-up.83

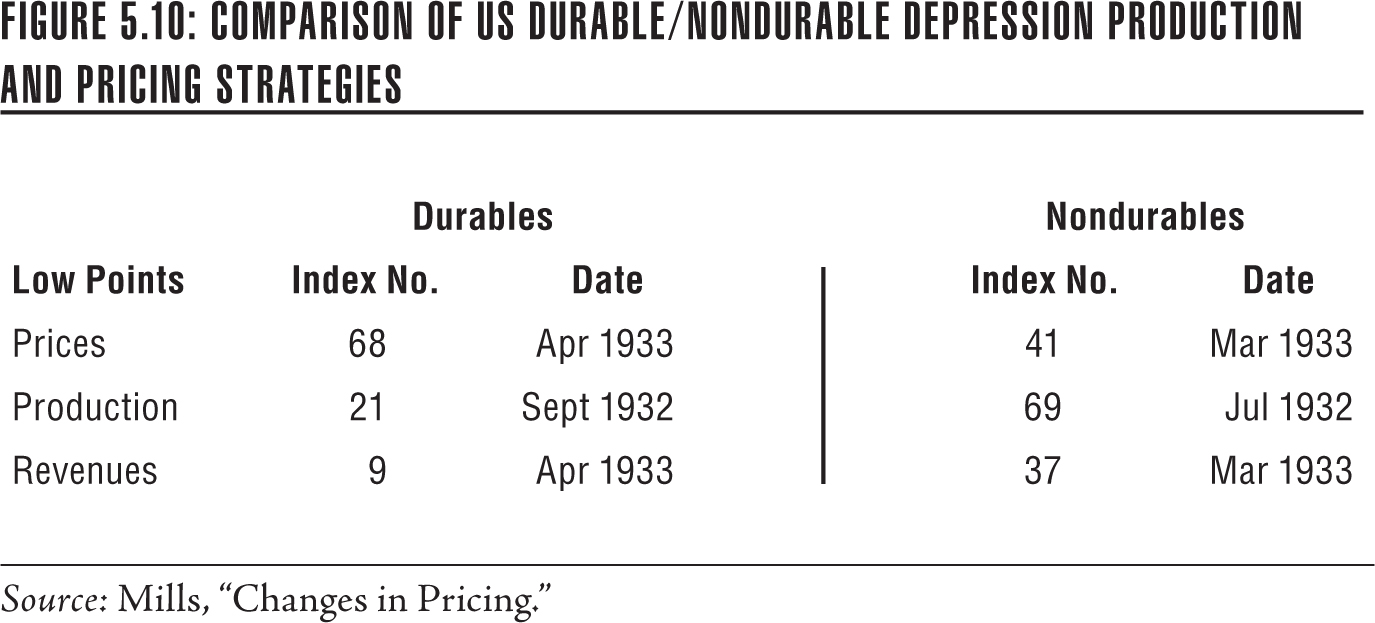

Nondurable manufacturers, as it happens, followed an opposite strategy. Instead of holding prices, they cut them, maintained higher production, and earned more than twice the level of revenues. See the comparison of low points (Figure 5.10) for each branch of the industry.84

The fact that manufacturing industries as a group adopted practices that split along durable and nondurable business lines suggests that there were business reasons for the choices. The inventory risk of durables and nondurables may have been quite different; perishable nondurables, for example, would tend to have short shelf lives. But the Time article quoted above suggests the prevalence of cartelized pricing in heavy manufacturing—a legacy of Elbert Gary’s long reign at US Steel.

The classical economic “law” that employment moves inversely to real wages was born in an era when great segments of society worked at routine jobs. Assuming a minimum set of physical skills and comprehension, laborers were laborers. The industrial revolution, however, spun off multiple new classes of artisans. When the United States was acquiring the technology for mechanized spinning and weaving, a skilled and ambitious artisan like the young Samuel Slater could emigrate from England, settle in a mercantile town like Providence, and rather quickly become rich. A generation or so later, textile mill mechanics were well paid—usually at the top of the blue-collar pyramid—but were no longer a scarce commodity.85

The advent of giant steam engines enabled much larger factories and forced capital deepening, which pushed up the wages of the most-skilled manual workers and increased the employment of white-collar workers—typically more highly educated, at ease with symbolic information, and more highly paid. Well into the early twentieth century, literate and numerate high school graduates commanded substantial pay premiums. The advent of AC wholesale electricity enabled yet another revolution in manufacturing, which Ford was the first to implement. Recall that in 1914, the first year the industry produced more than 500,000 cars, Ford produced nearly half of them, with only one-fifth the workers of his competitors.

The “Middletown” researchers who analyzed the mores, manners, and economic practices of the city of Muncie, Indiana, reported that Fordism had taken hold in the traditional Middletown manufacturing enterprises. Muncie’s plants mostly sold into the automobile industry in the 1920s; they were benefiting from the rocketing sales and were under great pressure to keep up technically with their customers. A generation before, Muncie’s manufacturers had employed skilled workers, who had completed formal apprenticeship programs and made all or substantial elements of a workpiece. Under Fordism, factories were staffed by operators who loaded machines and turned them on and off, or executed a small number of repetitive manual tasks. They could usually be trained within a few hours or, at most, a week or two, and the best Fordist lines produced parts that didn’t need special fitting. But the people running Muncie’s plants were not Henry Fords. A reasonable estimate is that it took about twenty years to implement full-bore Fordism in a major plant: it required great discipline in the setup, and fanatical attention to detail. It is likely that in Muncie most of the parts manufacturers did the job only partway, enough to qualify for contracts but without the tireless zeal to weed out all the diseconomies.*

Kenneth Roose, who wrote the first book-length account of the 1937 recession, noted with puzzlement that during the 1930s factory construction fell precipitately, while machine purchases rose quite dramatically.† In fact, that is direct evidence of the continued march of Fordism. Factories became single-floor, compact structures, with machines laid out to create the most efficient routes and travel times of workpieces. None of that was possible before the advent of purchased AC electricity. In steam-driven plants, machines were segregated by the heaviness of the belting, and multifloor layouts allowed driving multiple classes of machinery from a single drive. AC-drive plants became cleaner, brighter, and quieter. Roose’s puzzle, in other words, was the natural result of the continuing Fordist transition: factory construction costs were substantially reduced, but almost all of the machinery had to be replaced.86

Over the last couple of decades, there has been a welcome trend in economics to dig beneath aggregate data for the significant microdata that may determine events. Timothy Bresnahan and Daniel Raff have focused on such microdata in a series of studies that document the violent Depression-era shakeout in the automobile industry. Plant closings followed a clear pattern—in general, smaller plants closed and the larger ones survived. Discontinued plants on average were about half the size as the surviving plants and accounted for a third of the job losses. Some Big Three plants (Ford, GM, and Chrysler) were mothballed, but reopened as business picked up. Labor productivity fell somewhat at the surviving plants, suggesting some “labor hoarding”—retaining senior more highly paid men, while dismissing younger, less-skilled workers. White-collar workers were more protected; only about 25 percent were let go, compared to 50 percent of blue-collar workers.

As the market picked up after 1933, productivity responded dramatically. By 1935, vehicle production had doubled, while blue-collar employment had increased only by half, and white-collar employment was virtually unchanged, although overall productivity was still not quite at the blowout 1929 level. The number of plants had not increased from their 1933 low, but on average they were much bigger than their pre-Depression predecessors. In effect, the modern automobile industry—dominated by a few very large oligopolistic firms—took shape in the crucible of the Crash.87

The economist Richard Jensen, in a well-known paper that complements much of the Bresnahan-Raff work, points to the “efficiency wage” as a major factor in the persistent unemployment figures. Efficiency wage principles may well have influenced the Ford-Couzens decision to jump to the $5 pay standard in 1914. Their company was growing by leaps and bounds, but the discipline of a highly mechanized manufacturing operation system was a hard one, and turnover was a growing, and expensive, problem. While the company was very profitable, factory indiscipline may have been perceived as a real threat to future growth. While the record supports a belief that Ford and Couzens wanted to share their profits with the workers, they could have done that without doubling the wage. It was a bold decision and paid off magnificently.88

Jensen stresses that the day’s workers were not a homogeneous collective. Just as there were too-small, insufficiently rationalized, and essentially doomed auto manufacturers at the outset of the Depression, so there were workers who lacked the temperament, or the smarts, or the discipline to make their way in a modernized work environment—Jensen calls them the “hard-core.” Barriers to hiring such people were doubtless raised by the minimum wage and other provisions of the NIRA, and after its demise, successor legislation like the National Labor Relations Act and the Fair Labor Standards Act.89

Before 1930, with the near-total lack of a social safety net, people had to work and generally accepted the market wage. Data from 1885 to 1930 suggest that only 10–20 percent of the workforce had been unemployed for more than six months. In 1930, only about 1 percent of the workforce had been unemployed that long. But once the Crash hit, unemployment spread rapidly and, Jensen suggests, created a distinct tiering of the ranks of the unemployed. Part 3 recounts the astonishing unemployment levels in the big factory cities. Rural unemployment was probably at least as bad, but was less visible and mostly not counted.90

Employment, however, was very fluid. Even in the very depths of the Depression, factories hired a million workers every three or four months. But they were no longer hiring the next body in the shape-up. Each hire would be interviewed and questioned on his work history, pay rates, and personal habits. A sorting process to distinguish competent workers from warm bodies was gradually taking hold throughout industry. These were also practices that Ford had pioneered twenty years before, when he implemented his $5-per-day regime. The very existence of such studies evidences the professionalization of personnel management and the emergence of explicit sorting procedures that pushed the least capable workers to the end of the hiring queue.91

The impact of Depression-era unemployment varied widely among industries. The construction and manufacturing industries were the worst hit. In 1933, almost three-quarters of construction workers and 40 percent of manufacturing workers were jobless. The two industries were still hard hit in 1938, with 55 percent and 28 percent joblessness, respectively. With such numbers, relief work was a godsend, and, as we have already seen, there is evidence that the long-term unemployed settled into their lot, despite the rules that the assignments were supposed to be temporary. Supervisors bargained with WPA workers that if they took an available private job, they could return to the WPA slot if they were let go. In one documented instance of a mass termination—783,000 workers in August 1939—57 percent were back on relief within a year. It is interesting, too, that the wives of unemployed men not on relief were apt to find private employment, while the wives of men on relief were less likely to do so.92

There is no single answer to the question of why Depression-era unemployment was so intractable. Embattled companies upped their investment in machinery and husbanded their best workers, squeezing out whatever pips of productivity they could find. More explicit hiring standards inevitably left an indigestible lump of disqualified applicants that would grow or shrink depending on shifts in aggregate demand. The very long periods of unemployment that became routine in the 1930s must have inculcated the expectations of failure and attitudes of shiftlessness associated with “hard core” unemployment. The solution, however, came quickly—fifteen million men were called into service in 1940–1941, military contracts turned on the lights in disused plants, and seven-day, twelve hours a day factory shifts were suddenly routine.