PRELUDE

PRELUDE

Kaiser Wilhelm II, king of Prussia and emperor of Germany, was jubilant. It was the thirty-fifth day after the mobilization, and the German army was approaching Paris in three great arrays, with salients already as close as thirty miles from the city. The kaiser’s troops had traveled hundreds of miles, mostly on foot, moving the lines forward by almost six miles a day against the flower of the French army. Within a week, they were expected to have overwhelmed Paris and forced its surrender, bringing the war to a glorious close.*1

The kaiser was especially delighted because his armies’ positioning was almost precisely in accord with the “Schlieffen Plan,” the brainchild of Alfred von Schlieffen, the head of the German Imperial General Staff from 1890 to 1906. Schlieffen had calculated that on or about the fortieth day after the invasion of Belgium, France’s ally Russia would have completed its mobilization and begun to attack in the east. With Paris fallen, Russia would likely withdraw rather than fight alone against the full power of the German war machine, which could be rapidly deployed to the east by railroad. In 1914, war planning was the prerogative of General Helmuth von Moltke “the Younger,” the nephew of the great Helmuth von Moltke “the Elder,” who had masterminded the lightning six-week victory in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871, and preceded Schlieffen as chief of the general staff.

The elder Moltke believed that his stunning 1871 victory was not repeatable, in great part because the French had built such a strong system of fortresses from Verdun, just below the border with Belgium south to Belfort just above the northern border of Switzerland, effectively covering the approaches to France from German territory. Moltke was also one of the very few European commanders who had studied the American Civil War, and understood how easily two armies with vast numbers of well-equipped troops might fall into a prolonged stalemate.

Schlieffen was a brilliant tactician, but had a highly abstract conception of strategy, disdain for naval operations, and little feel for politics or the tug of nationalisms. He agreed with Moltke on the difficulties of attacking the formidable networks of French forts, and without apologies or compunction, developed a plan that depended on invading neutral Holland and Belgium to skirt the French defenses. German statesmen and generals, from the kaiser on down, seem to have readily adopted the plan, while piously swearing that they never would invade a neutral country unless their enemy had already invaded it. But their behavior betrayed their intentions, for the national railroad, which was essentially an arm of the military, was steadily reconfigured to support a massive movement of men and matériel to the Belgian and Dutch borders. As Winston Churchill pointed out in 1911: “The great military camps in close proximity to the frontier, the enormous depots, the reticulation of railways, the endless sidings, revealed with the utmost clearness and beyond all doubt [the German] design.”2

The “Schlieffen Plan” went through many iterations. The final version, the famous “1905 memorandum” assumed that practically all the German striking power would be in the right wing: it would comprise thirty-five corps—about a million men—who would strike France from the north through Amiens to Paris. The plan was for an essentially one-front war, save for a covering force of five corps to protect the coal-rich Alsace-Lorraine region that the Germans had taken from France in 1871. Schlieffen paid no attention to the possibility that Great Britain might be compelled to join France in the face of brutal attacks on neutral countries, perhaps a symptom of his tin ear for politics. He also paid no attention to the eastern front, which was reasonable enough in 1905, given the string of Russian fiascos in the 1904–1905 Russo-Japanese War. Ignoring Russia was not possible in 1914, however, since the tsar, with the help of France, had been diligently strengthening his military and had achieved several years of respectable industrial growth, although from a very low base.3

The military historian John Keegan has criticized the Schlieffen Plan for its rigidity and for its impracticality. Even in 1914, the German military did not dispose of the manpower that the plan required. (Schlieffen himself had expressed his doubts on the adequacy of the attacking force.) The marching times required for the extreme German right wing may have been impossible, and the timing of the attack took no account of the likely destruction of French bridges and rail lines. Schlieffen had insisted on an additional eight corps for the right wing—about 200,000 men—but while they could be accommodated by the railroads to the German borders, transportation would probably fail once they crossed into the neutral countries. Schlieffen and his successor as chief, the younger Moltke, ignored those constraints—as Keegan put it, the extra 200,000 troops “simply appear” outside Paris, an example of the “wishful thinking” that he finds throughout the plan.4

The younger Moltke was not of the same fiber as his uncle. He was a fine staff officer, but openly admitted that he might not be up to the job of chief of staff. “I lack the power of rapid decision,” he said. “I am too reflective, too scrupulous, or if you like too conscientious for such a post. I lack the capacity for risking all on a single throw.” He has been savagely criticized for his departures from the master plan, and the fairness of such criticisms is still debated today. One distinguished scholar, for example, heaps blame on Moltke, claiming that his changes in the Schlieffen Plan “had disastrous effects on the German prospects of victory in 1914… [and] effectively nullified his chances of victory,” while the military expert Liddell Hart commented that “Schlieffen’s formula for a quick victory amounted to little more than a gambler’s belief in the virtuosity of sheer audacity.”5

The spark that set off the war was the June 28 assassination of the Grand Duke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the throne of the Austrian-Hungarian empire and his wife, in Sarajevo.

The Balkans were seething with independence and pro-Slavic movements, often with the covert assistance of Russia, seeking to advance its vision of a great Slavic empire at the expense of Austria-Hungary’s Hapsburgs. In response to the assassination, Austria sent an ultimatum to Serbia, backed by a German note to other great powers. Serbia promptly mobilized, but much of this was posturing. In previous Balkan flare-ups, hostilities had been deflected by the intervention of the big powers. On cue, the British proposed an international conference. The French and Italian governments eagerly accepted the invitation, setting the stage for the time-honored face-saving adjustments that could usually keep an inherently unstable situation tottering along for another few years.

Austria, almost inadvertently it seems, refused to play by the script and mobilized against Serbia. Russia’s Tsar Nicholas, after hesitating a day, responded with a general mobilization, implicitly including Germany. The German government requested that Great Britain declare its neutrality, which they refused on July 30. On August 1, Germany mobilized, declared war on Russia, and demanded right of passage through Belgium. Over the next few days, Germany declared war on France and Belgium, and Great Britain declared war on Germany, cementing the alliance of France, Russia, and Great Britain against the “Central Powers,” led by Germany. The first elements of the German army crossed the Belgian border on August 4. All of these events transpired in an atmosphere of distrust, prevarication, hysteria, indecision, misunderstanding, and intentional misdirection.

John Maynard Keynes famously wrote:

What an extraordinary episode in the economic progress of man that age was which came to an end in August, 1914!… The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole earth, in such quantity as he might see fit, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep.… He could secure forthwith, if he wished it, cheap and comfortable means of transit to any country or climate without passport or other formality,… and could then proceed abroad to foreign quarters, without knowledge of their religion, language, or customs, bearing coined wealth upon his person, and would consider himself greatly aggrieved and much surprised at the least interference. But, most important of all, he regarded this state of affairs as normal, certain, and permanent.… The projects and politics of militarism and imperialism, of racial and cultural rivalries, of monopolies, restrictions, and exclusion, which were to play the serpent to this paradise, were little more than the amusements of his daily newspaper, and appeared to exercise almost no influence at all on the ordinary course of social and economic life.6

Keynes was eulogizing the high culture of Europe, its common heritage of Greek philosophy and Roman jurisprudence, the shared literature of Shakespeare, Molière, Schiller and Lessing, Tolstoy and Pushkin, the music of Mozart, Beethoven, and Verdi. Reminders of the ancientness of the common culture were everywhere, in the great cathedrals and castles and in the universities. Although most countries still had kings and queens, they usually ruled in accommodation with somewhat representative parliaments, amid slow but steady expansion of the franchise. There was an inchoate, but growing, attention to social insurance, the legacy of Germany’s great chancellor, Otto von Bismarck. A glittering international café society dazzled with its wit, its taste, its curiosity.

But those splendid vistas were constantly shadowed by the black specter of war. It was not an alien presence, but part of the same cultural inheritance. States maintained armies, polished battle plans, and declared wars. Wars were an essential element in maintaining a polity’s health and ensuring its progress. In his famous 1910 antiwar book, The Great Illusion, Norman Angell collected a sample of journalistic arguments for the obvious necessity for wars.

From the National Review: [Without] a powerful fleet, a perfect organization behind the fleet, and an army of defence… all security will disappear, and British commerce and industry… must rapidly decline, thus accentuating British national degeneracy and decadence.

From the Fortnightly Review: Does any man who understands the subject think there is… any power in the world that can prevent Germany… from now closing with Great Britain for her ultimate share of… overseas trade?… [This is] behind all the colossal armaments that indicate the present preparations for a new struggle for sea-power.

From the London World: Great Britain… exists by virtue of her foreign trade and her control of the carrying trade of the world; defeat in war would mean the transference of both to other hands and consequent starvation for a large percent of wage-earners.

And from Blackwood’s Magazine: We appear to have forgotten the fundamental truth… that the warlike races inherit the earth, and that Nature decrees the survival of the fittest.… Our… parrot-like repetition… that the “greatest of all British interests is peace”… must inevitably give to any people who covet our wealth and our possessions… the ambition to strike a swift and deadly blow at the heart of the Empire—undefended London.7

Germany had its own fears. The banker Max Warburg reported on an unsettling conversation with the kaiser in June 1914:

He was worried about the Russian armaments [programme and] about the planned railway construction and detected [in these] the preparations for war against us in 1916. He complained about the inadequacy of the railway-links that we had at the Western Front against France; and hinted [… ] whether it would not be better to strike now, rather than wait.

Warburg “decidedly advised against this,” citing British domestic politics, French military and financial problems, and the backwardness of the Russian military. He advised the kaiser “to wait patiently, keeping our heads down for a few more years. ‘We are growing stronger every year; our enemies are getting weaker internally.’”8

The general staff, however, fed the kaiser’s paranoia, and they had reasons for their discomfort. Germany was far from the most militarized nation in Europe. France took those honors, for a full 83 percent of its military-aged males had undergone serious military training, compared to 53 percent in Germany. Germany’s peacetime army was maintained at 761,000 men compared to 827,000 in France and 1,445,000 in Russia. In wartime the French-Russian/German-Austrian ratio became 5,200,000 to 3,485,000. Besides its huge population advantage, Russia was engaged in a surprisingly fast modernization program, much of it driven by the private sector and focused on railroads, electricity, and heavy industry. Germany also recently had been forced into a humiliating climb-down in a contest of Dreadnought battleship building with Great Britain.9

Much to the German generals’ chagrin, they had little success in pressing their views on the government. When they pleaded for expanded capabilities, the civilian war minister scoffed that “the entire structure of the army, instructors, barracks, etc., could not digest more recruits,” and blamed the constant badgering for more forces on the “agitation of the Army League and the Pan-Germans.” There was even subtle opposition to military expansion within the senior officers. The top echelons of the military were dominated by Prussian aristocrats, who were concerned about the dilution of quality that would follow upon an increasingly “technocratic” rather than aristocratic officer corps.10

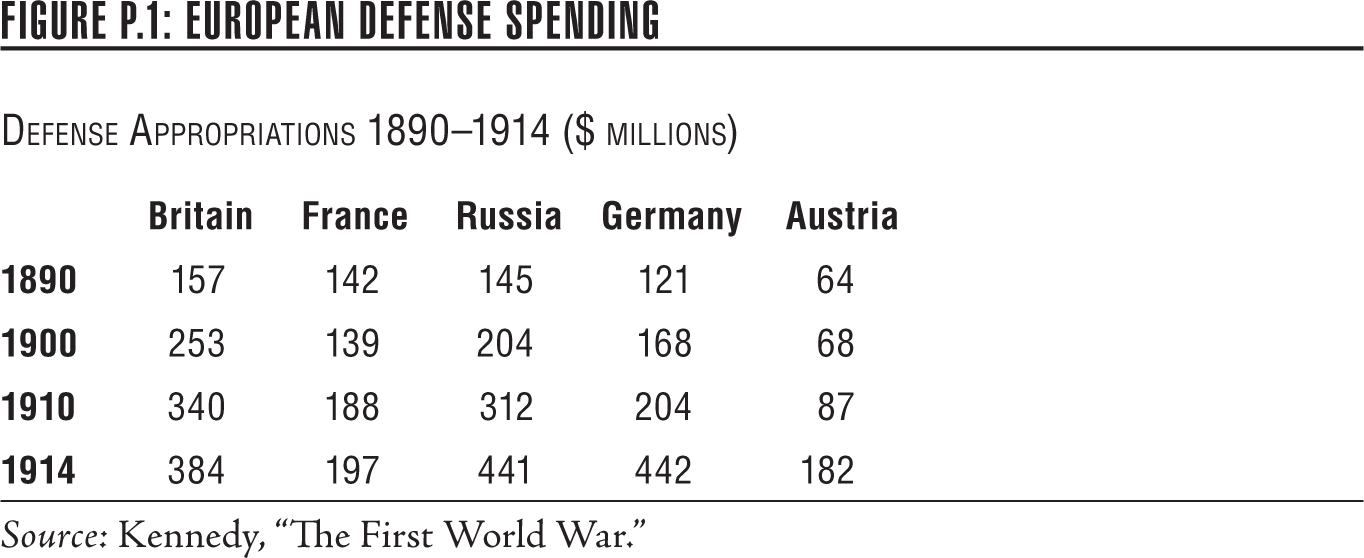

The pattern of European military spending supported the German generals’ case. Of the most likely combatants in a European war, the Germans, with their Austrian allies, were spending just over 60 percent of the total of Great Britain, France, and Russia (see Figure P. 1).

But much of that can be discounted. A war in Europe was likely to be primarily a ground war, with naval power largely used to blockade supplies. The British held a clear dominance of sea power, but were still debating whether and how much to build up their infantry when the war broke out. Russia had been arming prodigiously, but the quality of its military officers, its impoverished and torpid peasantry, and the deficiencies of its infrastructure greatly limited its effectiveness. The historian Paul Kennedy points out that, of all the European countries, Germany had much the best balance of economic and military power. Due to its rapid industrial growth it could bear its growing military burdens with “less strain than virtually every other combatant… and had enormous staying power.” Its populace may have been the best educated in Europe, its industrial production was greater than Britain’s, its steel production was greater than the British, French, and Russian combined, and it was a world leader in advanced industries like chemicals, machine tools, communications, and optics.11

German military capabilities reflected all those advantages. It was the only major power to have adjusted its military strategies to comport with the leaps in weapon technologies. Traditional land warfare was mostly a matter of men with rifles standing in a line and shooting at each other. The German military had evolved a strategy of “defense in depth,” with a zone of continuous defense with scattered small group outposts and machine gun nests firing at the attackers’ flanks. The same concepts, or “stormtroop tactics” applied to the offense, emphasizing rapid movement and rapid fire by small detachments with considerable independence. Other advances included trenching technology and synchronization of infantry and artillery practice, like the “creeping bombardment”—all of it backed up by careful analysis and institutionalization of proven innovations.

The German tactical edge was evident in their remarkable success in killing their opponents. Over the course of the war, 5.4 million combatants on the Allied side lost their lives, with the great majority killed by the enemy, while the Central Powers (Germany and Austria) lost 4 million, for a 35 percent net body count advantage. British statisticians had even higher figures, showing a 50 percent advantage for the Germans, although some of that difference doubtless stemmed from the allies’ penchant for mass attacks. One day’s battle at the Somme River—a British assault under Field Marshal Douglas Haig—cost the British 60,000 casualties against 8,000 for the Germans.12

When the German armies came pouring across the Belgian border, they met a populace ready to fight. The system of forts at Liège and Namur guarding the Meuse River crossings were formidable obstacles. The Liège system was twenty-five miles in circumference, with most of the buildings underground, disposing of twelve equally spaced forts with four hundred heavy guns, with the whole protected by a thirty-foot-deep moat. It took about a week for the Germans to destroy the Liège forts, and another two weeks to level Namur. The decisive weapons were four massive new artillery pieces, two from Krupp, and two from the Austrian Skoda, each more powerful than those on Dreadnought-class battleships. Once they had secured their passage, the Germans descended on the civilian population with vindictive fury. More than a thousand Belgian civilians were systematically massacred. The nadir of their revenge came on August 25, when the Germans torched the leafy university town of Louvain, the “Oxford of Belgium,” and its priceless trove of ancient manuscripts.13

The French had a war strategy of their own. General Joseph Joffre positioned the bulk of his armies in northeast France with access to Belgium and to Alsace-Lorraine, the “sacred” territory transferred to Germany after the 1870–1871 Franco-Prussian War. In effect, Joffre hoped to exploit the German focus on Belgium by unleashing a major attack to push them out of Alsace. It was badly misconceived. Alsace was well defended, and the Germans had by far the greater grasp of field tactics. At the first French attacks, the Germans retreated, sucking the French farther away from their support, and then fell on them. The French held several towns, then lost them, then held and lost them again.

By the last week in August 1914, the French were essentially fighting desperate holding actions all along their lines in a wide outward-facing semicircle that was centered on Paris. Its perimeter originally stretched from the channel ports along the Belgian and Luxembourg borders down to the western edges of the French Ardennes, but the whole space was rapidly imploding in the direction of Paris. By this time, a modest British Expeditionary Force (BEF), comprising one cavalry and four army divisions, had been landed on the channel ports to bolster the beleaguered French and Belgians. The BEF was immediately confronted by a powerful German army near the Belgian town of Mons. Although they gave a good account of themselves as steady fighters and marksmen, they were greatly outnumbered by the Germans, and they escaped only with heavy casualties. In the first two months of the war, the French suffered 329,000 killed in battle, a toll that rose to a half million by the end of 1914.

In the crisis, Joffre proved his mettle. He forthrightly recognized his own mistakes, fired dozens of nonperforming generals, and promoted younger high-fliers, including Ferdinand Foch, an aggressive and creative battle manager. Strategically, Joffre went into full retreat mode, with marching men carrying sixty-pound packs and covering as much as sixteen to twenty miles a day. Impressively, Joffre reconstituted the remnants of two nearly decimated armies into a new force, and organized the defense of Paris around the rivers of the Seine, the Marne, and the Ourcq on the north and eastern side.

Almost in parallel, Moltke’s weaknesses as a field commander began to be exposed. The pursuing German soldiers were energized by the prospect of a stunning victory, but they were as physically exhausted as their opponents. As their supply lines lengthened, their fighting ranks dwindled as they were redeployed in securing their rear, pacifying the civilian populations and managing prisoners. It was at that point, in the midst of the drive toward Paris, that Moltke, feeling victory was assured, detached two corps—at full strength about 70,000 men—for service in the east against Russia. This was not necessarily a violation of the Schlieffen Plan as many commentators have had it, for Russia had mobilized with surprising speed. Two separate massive armies entered East Prussia on August 15 and August 22, well ahead even of the French concentration of forces in the west. Worse, the Germans got badly pounded in an early artillery battle, and the commander in the east was showing signs of panicking. But a more confident commander than Moltke might have recognized the folly of endangering the essential goal of a quick victory in France for the sake of a minor reverse in a fringe area.

Moltke had also never been known for his skill in large-scale force management, and he clearly muffed the management of his forces closing on Paris around the Marne River. He failed to intervene in a dispute between two commanders, Karl von Bülow and Alexander von Kluck, that resulted in a glaring thirty-mile gap between their forces. Even worse, Moltke and his staff seem to have been unaware of Joffre’s repositioning of his forces. When Kluck was finally ordered to take his proper position, which would have closed the gap, he unwittingly exposed his flank on the Paris side to a large French army, which attacked vigorously. Kluck escaped, but it was a near thing. Bülow then maneuvered to help Kluck, and came under attack by another repositioned French force, which widened the German “gap” to forty miles. German aerial surveillance showed more French troops and an augmented BEF marching rapidly to exploit the opening. Moltke, probably correctly, decided that the position was irretrievable and ordered a pullback to higher country beyond the Aisne River east of Paris, about forty miles in his rear, where the Germans dug in.

The Battle of the Marne, as it was called, was a major strategic defeat for the Germans and a turning point in the war. It was succeeded by the so-called Race to the Sea. The German trenches on the Aisne anchored the southern end of the battle line. Both sides almost immediately tried to outflank each other at the battle line’s northern point. There was a series of sharp actions, the most famous of which may have been at the Belgian town of Ypres, “First Ypres” as it came to be called. It was bloodily contested, and on the Allied side, demonstrated exemplary cooperation between Foch and the BEF, which now included a division from India. Each action ended in stalemate locked in by trenching. By November, the line of trenches extended from below Paris all the way to the channel ports. The last few miles in soggy, dreary, Flanders was finally secured when the exhausted Belgians opened the sluices of the Yser River and flooded the area.

British soldiers and medics in Northern France, struggling in knee-deep mud transporting a wounded man. Soldiers’ stories of the war often reflected the demoralization that came from months or years of slogging through mud.

In retrospect, the successful defense of Paris was the climactic event of the war, in the sense that all those immense forces were frozen—it appeared permanently—in deadly embrace with the other. And they stayed frozen in those positions for four more horrible years. Towns like Ypres, Passchendaele, Amiens, Messines, and the Somme River all wrote their doleful, sadly repetitive, histories in blood and mud. Essentially the same battles were fought over and over, but with more lethal tools. Gas, tanks, armor-piercing shells, and aerial bombing were used freely by both sides. As time went on, the skills of both forces converged. The “peace-trained” German army—the elite professional core of the German forces—had been badly depleted, and their replacements were no better or worse than the green soldiers in the opposing trenches. The fortified lines on both sides thickened and became more invulnerable to attack.

As the war dragged on, the body counts steadily mounted—literally millions on both sides. Casualty counts are far from reliable, but near-consensus figures capture the horror: 500,000 casualties at the Battle of the Marne in 1914, 850,000 at Passchendaele in 1917, 1,000,000 at Verdun in 1916, 1,200,000 at the Somme in 1916, 1,500,000 during the German “Spring Offensive” in 1918, and 1,900,000 during the “Hundred Days” offensive that finally broke the German resistance and led to the armistice.

The breakthrough was made possible only by the sudden flood of millions of men and mountains of matériel from the United States. The influx more than countered the transfer of German forces from the Russian front in consequence of the 1918 Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. Under the pressure of a broad Allied summer offensive, the German army simply disintegrated; in a matter of days, sixteen divisions were lost, amid widespread reports of German soldiers refusing to fight. In mid-August 1918, General Ludendorf, the effective chief of staff, suggested that the kaiser might think about an armistice; just weeks later, he was pleading for peace at any price. And within another few weeks, both Ludendorf and the kaiser had fled the country.14

Total casualties were 32.8 million, including wounded, killed, and in prison at the war’s end, about 7.2 million of whom were killed in battle. Surplus civilian deaths from illness, starvation, and other causes have been crudely estimated at about 6.5 million. Total war spending was about $220 billion in current dollars, or about $5 trillion in 2016 prices.15

THE COST OF PEACE

Ordinary Germans could hardly believe that they had lost the war. Unlike in World War II, when Germans saw their homeland reduced to rubble, the fighting in World War I took place almost entirely on French and Belgian soil. At the time of the armistice, except in a few fringe areas, there were no Allied troops in Germany. Thomas Lamont, a senior Morgan banker, who was then acting as an unofficial adviser to President Wilson, described a visit to Germany passing through Verdun during the armistice negotiations. He was appalled by the “vast wasteland of gray stumps… and muddy shellholes and craters” and equally stunned by the contrast when they drove into Germany: it was Easter, and everyone was dressed in their best; the store windows were full, the children were rosy cheeked.*16

Germans had eyes to see as well. It was the German military that marched into Berlin after the armistice was signed, to be hailed by the chancellor, Friedrich Ebert, as troops returning “unconquered from the field of battle.” Allied troops, mostly American, took months to arrive and establish control. That set the stage for the “stab in the back” legend that Germany had been sold out by “pacifists, Jews, and socialists.” The officially cultivated sense of injustice fostered pervasive violations of the German peace treaty obligations. Matthias Erzberger, the German armistice commissioner who signed the documents, was assassinated in 1921.17

France had suffered dreadfully in the war. It had lost a quarter of its military-age youth, its northern industrial areas had been almost utterly wasted, and the Germans had taken particular care to destroy key industrial assets—flooding mines, smashing machine tools, shipping home agricultural equipment—meticulously documenting the economic havoc they were inflicting. The stripping of Belgium by German troops was, if anything, even worse than in France, and both countries were desperate for reasonable reparations to restart their economies. Great Britain, on the other hand, was not nearly as bloody-minded. Their casualties had been dreadful, but the death rate was only about half that of France. (The toll on sons of the upper classes, however, was devastating—20 percent of former Eton pupils in the armed forces were killed.) But the war had not come to the home country, there were no daily reminders of physical devastation, and British statesmen were far more anxious to resume their lucrative trading relationship with Germany than to exact punishment.18

The Versailles Peace Conference officially convened in Paris on January 18, 1919. There were twenty-nine nations* represented—any country with a plausible claim to have been on the winning side was invited. The Germans and Austrians were pointedly excluded, signaling that this would be an imposed, rather than a negotiated treaty. The key parties were Georges Clémenceau, the French prime minister, David Lloyd George, the British prime minister, and Woodrow Wilson, the American president. When Wilson’s ship arrived in France, he was treated like a conquering hero. His right-hand man Colonel Edward House had been circulating Wilson’s “Fourteen Points” as the large-minded and “Christian” path to reasonable settlements. Clémenceau and George viewed them as lovely sentiments, but about as relevant to a war settlement as, say, Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount. The Germans were particularly enamored of Wilson because he had made statements that his points implied “no annexations, no contributions, no punitive damages.” But the Fourteen Points expressly allowed monetary restitution: Point VII and Point VIII specified that the damage done to Belgium and France must be “restored.” (Wilson insisted that those clauses covered only restitution for damage done by unlawful acts of war, and not for the parties’ own war costs, but that just shifted the issue of allocating the charges.)19

Much of the work of the Versailles conference was accomplished by the chief ministers of the Western powers. From left to right: Prime Ministers David Lloyd George (Britain), Vittorio Orlando (Italy), Georges Clémenceau (France), and US President Woodrow Wilson

The Germans were deeply offended at being shut out of the treaty discussions, and were distraught and angry when they got the final terms. They objected strongly to the famous Article 231, the “war guilt” clause for holding Germany accountable for starting the war, arguing that all the great powers were complicit. They strongly objected to losing territory and German-speaking populations. They were deeply aggrieved by the necessity of paying reparations, the more so since the treaty did not specify a limit, leaving that to a later conference of experts. And they were disdainful of Wilson, who they felt had betrayed his principles, and had simply caved to the French. The British tended to agree with the Germans, and John Maynard Keynes made a best seller out of his savagely sarcastic The Economic Consequences of the Peace.20

A vast literature has sprung up on the post-Versailles attempts at final war settlements. The French, by bitter experience, had learned to fear German expansionism, its growing population, its military and industrial prowess. Reparations were hardly unfair given the diligence with which the Germans destroyed French and Belgian industrial infrastructure. The final number, in fact, after being massaged by various international expert panels, was about what Keynes had said would be reasonable. In proportion to Germany’s wealth, it was certainly no more than the 5 billion gold French franc indemnity that Germany imposed on France at the end of the 1870–1871 war—in addition to the annexation of the rich coal district of Alsace-Lorraine. Germany finally paid about half of the reparations, the great part of it with borrowed money that was never repaid.

A fitting symbol of Versailles may have been the pathetic figure of Woodrow Wilson, incapacitated by a stroke, grimly refusing compromise with the American Senate, at the cost of scotching American membership in his cherished League of Nations. It was a sour ending to a dreadful decade. Europe was awash with fear and mistrust. Its markets were broken, its treasuries impoverished, its populations restive, and radicals of the left and the right were sowing violence and disorder. In most countries, governments were dysfunctional, alternating between inflationary binges and harsh monetary repression. The forces that caused the Great Depression originated in the disordered aftermath of World War I. Absent the war, it is almost impossible to imagine a Great Depression.