23 - The Treaty and its Bitter Fruit

The word ‘treaty’ has a peaceful connotation, but the Treaty ending the Irish War of Independence brought in its train a bitter civil war and the jailing and killing of those on either side who had been, for three years, comrades-in-arms, friends, neighbours, even brothers, united against their common foe.

When the Irish delegates signed the Treaty, the families of the executed leaders of Easter Week would have none of it, and its narrow victory in Dáil Éireann – sixty-four votes to fifty-seven – reflected the scope of the division and was a warning of the horror that was to come. Cumann na mBan returned an overwhelming 419 votes to 63 against the Treaty. None of the Gifford daughters favoured it.

Both sides, for and against, tried at first to compromise, but they also began to build up their armies. The new pro-Treaty Free State, as it was called, was eventually recruiting its soldiers at the rate of 300 per day under the Minister for Defence, Richard Mulcahy, and the Chief of Staff, Eoin O’Duffy. Both men were determined to defeat the anti-Treaty republican army. Many of their Free State recruits were desperate for a paid job.

The opposing, republican army was under the leadership of men such as Liam Lynch, Liam Mellows, Cathal Brugha, Oscar Traynor, Tom Barry and Rory O’Connor. De Valera joined them later. Revolted at what was happening to fellow nationalists in the north of Ireland they aimed to form a military dictatorship and to continue the War of Independence. The Westminster government was seen by them as duping the Treatyites with their promise of a boundary commission, which was supposed to safeguard northern nationalists.

In the south, sporadic killings were inflicted on and suffered by both the Free State and republican armies, but just as the shots at Soloheadbeg historically marked the opening of the War of Independence, so the occupation of the Four Courts by a detachment of the republican army marked the first significant confrontation of the Civil War.

R. M. Fox’s metaphorical reference to Grace Gifford-Plunkett on the roof of the Four Courts in June 1922, blowing a bugle to summon support for the republicans has, on occasion, been taken literally: ‘Sometimes she seems a gay, graceful figure … with a reed to her lips, dancing on; then I see her as the young bugler – whom I saw perched on the dome of the Four Courts in 1922.’[1]

But Grace climbed no roofs nor did she use either bugle or reed. She did speak, however, with her artist’s brush and, apart from her letters to the press disavowing the Treaty, produced one of her devastating political cartoons: Griffith had called Erskine Childers, who opposed the Treaty, a ‘damned Englishman’. Her cartoon depicts Griffith and Collins, dressed in Union Jack swimsuits, entering a sea marked ‘British Citizenship’. Childers is turning back to the shore marked ‘Irish republicanism’. Neither Griffith nor Collins can have been amused.

During those Civil War years, women republicans remained active and supportive of the men, just as they had during Easter Week and during the War of Independence. The statistics bear this out: hundreds of women were jailed by the Free State. In fact, what might be called the Easter Week names, such as Pearse, Plunkett, Clarke, Connolly, Mac Diarmada, MacDonagh, Heuston, MacBride, Mallin, de Valera, Daly and Ceannt never featured on pro-Treaty documents. The women of these families remained opposed to the Treaty, an embarrassing thorn in the Free State body politic’s side. The anti-Treatyites included all five of the surviving Gifford daughters, in both Ireland and America.

Nellie came back to Ireland in 1920 with her little daughter, Maeve. Her marriage was in trouble, and her mother, Isabella, who had accepted, only with some misgivings, the marriage of her other daughter, Muriel, in a Catholic church, asked of Nellie’s wedding, ‘What can you expect of a registry-office ceremony?’

Sadly, Maeve, child of the union, retained only one vague, visual image of the handsome father she so resembled – a man coming towards her with a balloon in his hand, so pathetically reminiscent of the memory of her cousin, Donagh MacDonagh, of his father Thomas: ‘A uniformed figure on a motorbike, who gave me a red wagon.’[2]Joseph Donnelly gave support for Maeve until she was about twelve years of age. His mother had also disapproved of the American registry-office marriage, and the Gifford family believed that on his visits home she deliberately introduced him to marriageable Catholic girls.[3]Joseph did remarry, though Nellie never did, and had another daughter with his second wife. She and her daughter contacted Maeve years later. Maeve, however, though she availed of an invitation to their home, and though her father and mother were long dead at this stage, did not pursue the proffered friendship. She felt it would be disloyal to her mother.[4]

Things were tight for Nellie financially, but she acquired a small red-brick house near the Royal Canal in Drumcondra and let a side flat to supplement her income. Her heart and soul were anti-Treaty, but she felt, trying to cope with straitened circumstances and with her young daughter to rear, that she could not devote time to politics as she had in her single days.

‘John’ had a different approach. When she returned to Ireland in 1922, the Civil War was under way. Her American marriage was over, the result of both partners wanting to settle in their native place: Arpad Czira went back to Hungary, leaving her with four-year-old Finian to rear. Despite that, she immediately identified herself with the ‘Mothers’, anti-Treatyites one and all, who were given this patronising title by the ‘Free Staters’, though their relationship with the jailed or executed anti-Treaty leaders might have been mother, daughter, cousin, girlfriend or sister. ‘John’s’ relationship was sister-in-law – twice over – to Plunkett and MacDonagh, and that made her a ‘Mother’.

Before leaving for America, apart from her budding career as a republican journalist, ‘John’ had always identified herself enthusiastically with many facets of the nationalist movement, from her submission of republican articles to Arthur Griffith in her teens, to her membership of Inghínidhe na hÉireann with a view to helping to launch the women’s paper which became Bean na hÉireann, seeking the betterment of women’s health and lives. There was later a general enlargement and embodiment of aims so that the Inghínidhe could amalgamate with Cumann na nGaelhael and later with the Dungannon Clubs (IRB). That organisation’s paper, Irish Freedom, replaced Bean na hÉireann, but ‘John’ was as happy writing for one as the other. She had never contributed to such publications as The Irish Homestead, whose images were those of the ‘Irish Coleen’ in red petticoat and shawl, and she had alienated the Irish Women’s Franchise League (IWFL) – the Irish suffragettes – by her suggestion that a significant move for Irish women would be another all-Irish school. As far as the IWFL was concerned, the Gaelicisation of Irish women took second place to their enfranchisement. An interesting letter to the Irish Independent from Grace repudiates the necessity for a women’s franchise league because the 1916 Proclamation clearly granted women equal status.

Despite this and other differences, ‘John’ had become a distinctive voice in republican women’s circles, and, before her American sojourn, she had reached executive status in Sinn Féin, along with Jenny Wyse Power and Countess Markievicz. Her fellow republicans welcomed her back from America with open arms, and she reciprocated with unbounded enthusiasm and commitment. She was a women before her time in that she managed to blend motherhood with her socio-political involvements, much as many women have learned to do with business and home today. Both she, Kate and Grace were frequent participants in the Sackville Street meetings of the ‘Mothers’, held symbolically on the debris of the ruined buildings. They were members of the Women’s Prisoners’ Defence League (WPDL) and frequently held public protests, including vigils outside jails against executions by the Irish Free State. They also smuggled guns, offered safe houses to republicans and sent food parcels to jailed prisoners. Grace lent her artistic talent by producing political cartoons, as usual, and Kate her general ability, especially on the matter of money management. It was like a continuation of the War of Independence, only the foe had changed: no longer Britain but now the Irish Free State.

The government of that state, however, was slowly but determinedly closing in on them. The WPDL was prorogued in January 1923, so the ladies changed the name and held a march in Sackville Street. Helena Molony mounted a lorry marked ‘The People’s Rights Association’ and quoted Shakespeare to remind the Free State authorities – and her audience – ‘a rose by any other name would smell as sweet’. So they continued shifting name and venue. These intrepid women seemed immune to being hosed with water and shot at and having their houses raided. Nor did they confine their activities to Dublin: ‘John’ Gifford-Czira addressed a protest meeting outside Portlaoise Jail.

In March 1922, before the taking of the Four Courts by the republican side, Grace wrote a letter to the press rebutting the expressed opinion of a journalist who urged acceptance of the Treaty as comparable to Plunkett marching with his white flag of surrender: both, he argued, were an acceptance of reality. Grace replied: ‘Joseph Plunkett, marching with white flag, surrendered – but only his body. He gave his life rather than take a shameful oath of allegiance to the Empire.’[5] She argued that the Republic, including the whole of Ireland, was a living reality, the Treaty its abandonment. In another letter, however, she defends the contributions of both Griffith and de Valera to win that republic and asks that this not be forgotten in rejecting the Treaty, though nevertheless urging its rejection. This magnanimity changed, however, with the outbreak of the Civil War.

The lives lost in the Civil War were Ireland’s loss. The execution of men such as Liam Mellows, Erskine Childers, Rory O’Connor, Joe McKelvey and Richard Barrett made a sad litany. In July 1922, Grace was among those who distributed leaflets at the funeral of Cathal Brugha, asking anyone who repudiated his anti-Treaty republicanism to leave the funeral obsequies. It was harsh, but many Free Staters obeyed and left.

Utterly strained with it all, Arthur Griffith died in August 1922. Ten days later, the bitterness reached its nadir with the ambush and killing of Griffith’s fellow negotiator, Michael Collins, on 22 August. The country mourned Collins, on both sides of the divide. His commitment to the north of Ireland had never wavered, and he stated publicly in Armagh, before the London negotiations, ‘No matter what the future may bring, we shall not desert you.’[6]Commandant General Tom Barry of the republican army gave an extraordinary description of the reaction of 1,000 republican prisoners in Kilmainham Gaol when they heard that their political opponent, Collins, had been killed by fellow republicans: ‘There was a stunned silence before the prisoners spontaneously knelt down and recited the rosary for their “enemy”, and their one-time colleague and friend.’[7]

Griffith’s successor, W. T. Cosgrave, handed over the quelling of the Civil War to the military authorities. They responded ruthlessly, some argue necessarily so, to avoid the possibility of anarchy. Violence of self-termed idealists was met by ruthlessness of self-termed realists. Deputy Seán Hales was assassinated by republicans. In retaliation, and without trial, Joseph McKelvey, Rory O’Connor, Liam Mellows and Richard Barrett fell to the executioner’s bullets in Mountjoy Jail, and, at that, even Free Staters felt uneasy. But the authorities were inexorable. Apart from the executions, about 12,000 republicans were jailed, of whom 400 were women, amongst them two of the Giffords, Kate and Grace.

On 6 February 1923, a party of Free State soldiers arrived at Kate’s residence at Philipsburgh Avenue and proceeded to ransack the house, looking for guns and incriminating documents. According to Maeve Donnelly, she, her mother (Nellie), her aunts Kate, Grace and ‘John’, with ‘John’s’ five-year-old son Finian, were present when the raid occurred. Grace was the more distressed of the two resident sisters, and Maeve remembered this distress, and the reason for it.[8]Grace was a tidy person, and in the pre-nylon days ladies wore lisle stockings, which, when laddered, were carefully darned. Grace had two drawers for her stockings: one for her best (unladdered) and another for her second-best (darned). The sight of a young Free State soldier rooting through these drawers to seek a gun or papers was the cause of her chagrin. Had she known what lay in store for both her and Kate at Kilmainham Gaol, she might have been less concerned at the rummaging through her hosiery.

It was, of course, Grace’s second visit to the awful jail. She knew well the discomforts of the dark old place – its dripping walls, lack of heating and small cells, without even basic furnishing. Yet there was another side to its discomforts: a sort of Frongochian comradeship got the women through their ordeal as it had done the men of Easter Week who were detained in Wales. Their friends were there, including Maud Gonne and also Dr Kathleen Lynn, for whom it was a second incarceration. They could have food parcels sent in, and their friends and family gathered outside on the banks of the River Camac to communicate with them, long distance, as shown in the picture of the hatted women visitors by John B. Yeats, shouting up their news to the prisoners who had gone to the top landing to ‘communicate’. Yeats painted this while Grace and Kate were prisoners at Kilmainham.

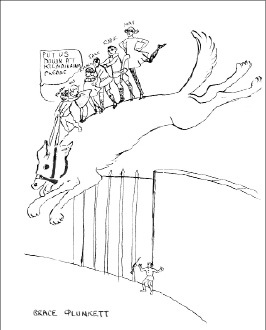

Grace herself, in contrast, produced a typically humorous sketch of the visits – a ‘glass half full’ approach to the visiting restriction in contrast to Yeats’ ‘glass half empty’ representation. Mary Kelly lived with her six children at 155 North Circular Road. Hers was a ‘safe house’ and had been visited by Connolly, Pearse, MacDonagh and, later, by Kate Gifford. When Grace was arrested during the Civil War, she left with Mary the gun which Joseph Plunkett had sent her on Easter Saturday 1916, which had been leant to Nellie for the Rising. Throughout Grace’s imprisonment in Kilmainham Gaol during the Civil War, the Kelly family – Mary, her six children and the family dog Rex – visited her every Sunday, bringing her baked delicacies to supplement the prison diet. Eddie, the eldest boy, a teenager, brought her paints and brushes with which she painted the ‘Kilmainham Madonna’. In a not untypical impish mood, Grace imagined and painted one visit where Rex became a lion or a panther, vaulting effortlessly over the closed jail gate. On his back was the eldest daughter, May, nonchalantly doing a dance, and with her are her five siblings – Eddie, Jack, Frances, Gus and Ciarán.[9] The guard, a Free State soldier, his rifle abandoned, is holding up his hands in surrender. Ciarán, the baby, is guiding their transporter with the reins and issuing an order: ‘Put us down at Kilmainham please.’ The sketch reflects Grace’s buoyancy of spirit and also her appreciation of how those visits must have brightened the jail’s drabness. Grace showed her appreciation materially when her circumstances improved, and she brought Mary with her on a holiday to Rothesay in Scotland, and later on, to Paris.

The sketch’s light-heartedness was remembered over the years by three of the Kelly family. A phone call to an Australian Kelly, Aoife Duffy (née Kelly), was successful: the long-lost picture had been found, and its copy, reproduced below, adds a very interesting example of Grace’s sense of humour.

With the paints and brushes which young Eddie Kelly had brought to the jail, Grace painted on her cell wall a very beautiful image of the Madonna and Child. Unfortunately, the deterioration of the prison before its restoration did not spare this historic picture. I have a very vague memory of seeing it as a child when I played in the crumbling jail with the caretaker’s daughter. There is a misted, distant sense of its being more ‘comfortable’ than the usual images of the Virgin depicted in statues and ‘holy pictures’ – those blue-eyed ladies with doll-like babies in their arms.

In a Kerry newspaper a picture appeared with the caption Copy of the Original Kilmainham Madonna. Miss Hannah O’Connor of Ballymullen had admired the Madonna on her fellow prisoner’s wall in 1923. Grace thanked her and promised to do an exact copy in Hannah’s autograph book. She drew a very beautiful and very Jewish Madonna for Hannah, signing it with her name and address. It is not an exact copy: the infant – and cloak – are different, but there is still a palpable warmth about it, a little reminiscent of certain Renaissance Madonnas and Russian icons.[10]

In the 1960s, Thomas Ryan, later President of the Royal Hibernian Academy of Arts, was asked to ‘retouch’ the picture. At that stage, replastering, dampness and neglect had done their worst, and it is hardly fair to question, as has been done, Ryan’s renovative work. He decided to change the Virgin’s cloak from blue to red, and though she herself lacks the free-flowing gracefulness that characterised the original, the artist still avoided the relative lifelessness of the twentieth-century Italian madonnas.

As the men had done in Frongoch, the women imprisoned in Kilmainham also had classes – in language, history and dancing. Autograph books, a legacy of Frongoch, featured also in Kilmainham. Both Grace and Kate contributed. In some, Kate expressed determination for the cause; others she merely signed – bilingually, giving her prison number and her two prisons:

Cáit Bean Mich Liaim

(Catherine Gifford Wilson – 3102)

Kilmainham and NDU 29.viii.1923

In another of the autograph books, the NDU (North Dublin Union), an institution to which they were transferred in 1923, is described as Tig na mBocht (the House of the Poor), which, of course, it had been before it was taken over by the British military in 1918, and there is later a brief reference to an incident in prison: Grace is described as trying to escape through barbed wire by throwing a blanket over it. It would not have been out of character.[11]

In May 1923, the women organised a special commemorative ceremony of Easter Week: they marched into the execution yard, Grace unfurled the tricolour, laid a wreath and spoke about her husband; Éamonn Ceannt’s sister-in-law spoke of his part in the Rising; and, to conclude the sad little ceremony, the rosary was led by The O’Rahilly’s sister-in-law. That emotional day concluded with a concert and included a recital of compositions by Plunkett and Pearse. It ended with the singing of ‘Amhrán na bhFiann’, an enthusiastic translation of ‘The Soldier’s Song’ which became the Irish national anthem.

The pleasantries of Kilmainham Gaol helped, but the women were all to taste the darker side of imprisonment. The historian Dorothy Macardle was a prisoner there at the time and has left a vivid and disturbing picture of their efforts to stay in the prison to comfort two of the prisoners on hunger strike: Kate O’Callaghan (widow of Michael, Lord Mayor of Limerick) and Mary MacSwiney (sister of Terence, Lord Mayor of Cork) who had argued that the Treaty was ‘the one unforgivable crime that has ever been committed by representatives of the people of Ireland’.[12] The women feared that the two hunger strikers would be force-fed if they were left as the only prisoners in the jail. Both women were quite ill, especially Kate O’Callaghan, and the other prisoners used to sing outside their cells every evening to cheer them up. The bulk of the women had already won some privileges by going on hunger strike, but this time the authorities seemed adamant: they wanted to isolate O’Callaghan and MacSwiney. At 3 p.m. one afternoon, the nineteenth day of the hunger strike, the Governor notified the objectors that the prisoners were to be removed to the NDU, the former poorhouse, that evening, leaving the two hunger strikers behind. The reaction was unanimous: the hunger strikers must first be released. At 9 p.m., Governor Begley sent word that eighty-one prisoners would be removed, if necessary by force. When asked if woman-beating was a soldier’s work, he replied, unbelievably, ‘I have beaten my wife.’[13] Then word came to the women of Kate O’Callaghan’s release but not of Mary MacSwiney’s. They decided on a sit-in on the top gallery of the compound, with instructions to resist but not attack and to avoid helping each other: passive but determined resistance was the idea, and no one was to cry out, to avoid upsetting the remaining hunger striker. They knelt and said the rosary.

After that they stood three deep and sang Mary MacSwiney’s favourite songs, fastening the doors of the cells as they waited in darkness, only one lit window illuminating the huge place. At 10 p.m. their leaders were called to Mr O’Neill, Governor of the NDU. Much softer in his approach than the wife-beating Begley, he promised that if eighty-one would go quietly to the NDU, no others would be sent away before Miss MacSwiney and that if they failed to cooperate, their privileges would be withdrawn. They had ten minutes to decide. Their answer was no.

Next, a worried matron, carrying a lighted taper, came to tell them that it was not soldiers but the Criminal Investigation Division and military police who would eject them, both of whose members she described as ‘horrible men’. She was wasting her well-intentioned intervention, but she was right about the men, whose violent rush up the stairs brought down the first two girls, crushed and bruised. Dorothy Macardle’s words describe what followed:

Our Commandant, Mrs Gordon, was the next to be attacked. It was hard not to go to her rescue. She clung to the iron bars, the men beat her hands with their clenched fists again and again; that failed to make her loose her hold, and they struck her twice in the chest; then one took her head and beat it against the iron bars. I think she was unconscious after that; I saw her dragged by the soldiers down the stairs, all across the compound and out at the gate.

The men seemed skilled; they had many methods. Some twisted the girls’ arms, some bent back their thumbs; one who seized Iseult Stuart kicked her on the stairs with his knee. Brigid O’Mullane, Sheila Hartnett, Roisín Ryan and Melina Phelan were kicked by a Criminal Investigation Department man who used his feet. Florence MacDermott was disabled by a blow on the ankle with a revolver; Annie McKeown, one of the smallest and youngest, was pulled downstairs and kicked, perhaps accidentally, on the head. One girl had her finger bitten. Sheila Bowen fell with a heart attack. Lily Dunn and May O’Toole, who have been very ill, fainted; they do not know where they were struck. There was one man with a blackened face. When my own turn came, after I had been dragged from the railings, a great hand closed on my face, blinding and stifling me, and thrust me back down to the ground among trampling feet. I heard someone who saw it scream and wondered how Miss MacSwiney would bear the noise. After that I remember being carried by two or three men and flung down in the surgery to be searched. Mrs Wilson and Mrs Gordon were there, their faces bleeding. One of the women searchers was screaming at them like a drunkard in Camden Street on a Saturday night; she struck Mrs Gordon in the face. In spite of a few violent efforts to pinion us they did not persist in searching us. They had had their lesson in Mountjoy. They contented themselves with removing watches, fountain pens and brooches, kicking Peg Flanagan and beating Kathleen O’Carroll on the head with her shoe.

I stood in the passage then, waiting for the girls to be flung out, one by one. None were frightened or overcome, but many were half-fainting. Lena O’Doherty had been struck on the mouth; one man had thrust a finger down Moira Broderick’s throat. Many of the men were smoking all the time. Some soldiers who were on guard there looked wretched; the wardresses were bringing us cups of water; they were crying. The prison doctor seemed amused at the spectacle until the women were finally thrown into the waiting lorry, the whole procedure having taken five hours.[14]

The Mrs Wilson whose face was bleeding was, of course, Kate, the eldest Gifford daughter.

It was an ugly business, but just as ugly, in a different sense, was the observation of Kevin O’Higgins. He was Minister for Home Affairs at the time and referred contemptuously to the Kilmainham Gaol disturbances as being caused by ‘hysterical young women who ought to be playing five-fingered exercises or helping their mothers with the brasses’. He conveniently forgot the huge input of the Easter Week women, from Countess Markievicz’s command at the Royal College of Surgeons to the lone figure of Nurse O’Farrell carrying her improvised white flag of surrender through streets where she could have met her end at any moment. O’Higgins is said to have been the last minister to sign the execution order for the four republicans shot in Mountjoy in 1922, perhaps reluctantly because one of them, Rory O’Connor, had been best man at his wedding.

O’Higgins himself did not die immediately when shot by republicans after the Civil War had ended, and Roger Gannon, son of Bill Gannon, one of the three assassins of O’Higgins in 1927, approached his daughter Una O’Higgins O’Malley with an account of the shooting given to him by his father during his last illness.[15]The story was that O’Higgins had told his attackers that he understood why they had shot him, that he forgave them, but that this had to be the last killing.

Doubts have been expressed about the authenticity of this account, but Roger Gannon’s disclosure emerged as a result of a commemorative mass, publicly announced for ‘Kevin O’Higgins, Tim Coughlan, Archie Doyle and Bill Gannon’. Its bonding of the assassinated and the assassins touched a chord and prompted Roger Gannon to pass on his story, and the account indicates magnanimity in O’Higgins, despite the four executions and despite his contemptuous dismissal of the role of republican women in the War of Independence.

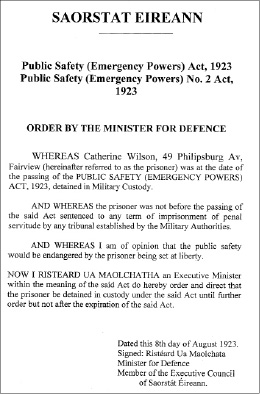

The jailed women at Kilmainham, including Isabella’s imprisoned daughters, Kate and Grace, were all duly bundled into the NDU from the lorries that had taken them from Kilmainham Gaol. Documents held there indicate a difference made between the sisters. The records are as follows:

Philipsburgh Ave. Fairview – PLUNKETT, MRS GRACE; date of arrival 6/2/23. Also brought to NDU. Release date 13/8/23.

Prisoner number 3101.

Philipsburgh Ave. Fairview – WILSON, MRS CATHERINE; date of arrival 6/2/23. Also brought to NDU. Release date 28/9/23.

Released from NDU, number 3102.[16]

These dates show that Grace was imprisoned for almost seven months. There is no indication why Kate was detained in prison for almost seven weeks longer than Grace, who, in fact, on being told of her forthcoming release, informed the authorities that she refused to go without her sister. They told her that she could either go quietly or be removed by force. No doubt Kate counselled her to go. Perhaps Grace’s presence was an embarrassment to the Free State, her being the widow of a signatory of the Proclamation. Whatever the reason, her sister’s detention order makes strange reading:

This most gracious lady a danger to public safety? One wonders from where did this Kate emerge. The faces of all who knew her lit up at the mention of her name: soft-voiced gentleness, kindness and academic ability were the images conveyed – the paragon of the Gifford family, one of the Giffords whom Countess Plunkett and her daughter Geraldine found charming, the chosen executrix for both her parents’ wills, the respected language teacher, the mother figure for her junior siblings, the lady who was to leave behind her a legacy of loving memories – this Kate Gifford-Wilson was considered by the Free State to be a danger to public safety. What on earth did her mother think of her solid Kate being described as a danger to the state? Of the six unlikely rebels whom Isabella had bred and nurtured, this lady was surely the most unlikely to be such a danger.

When Kate was released from the NDU on 28 September 1923, the Civil War was already over. Liam Lynch was dead, and Frank Aiken, the new Chief of Staff of the IRA, declared a ceasefire for republicans. The Irish Free State was tottering along awkwardly but determinedly, a nation taking its first steps of partial freedom since the twelfth century.

Notes

[1] R. M. Fox, Rebel Irishwomen, Dublin: Talbot Press, 1935, pp. 75–89.

[2] In conversation with Maeve Donnelly in the early 1990s; An Cosantóir, August 1945, vol. V, no. 10, p. 534.

[3] In conversation with Maeve Donnelly in the early 1990s.

[4]Ibid.

[5] ‘The White Flag of the Republic’, The Republic, March 1922. Grace published a similar argument in the Irish Independent.

[6] T. Ryle Dwyer, Michael Collins and the Treaty: His Differences with De Valera, Cork: Mercier Press, 1981.

[7] Tom Barry, Guerilla Days in Ireland, Dublin: Anvil Books, 1981, pp. 168–169.

[8] In conversation with Maeve Donnelly in the early 1990s.

[9] Grace has used a different spelling for Ciarán’s name. ‘Gus’ was the pet name for Gabrielle, whose daughter, Aoife, preserved the sketch in Australia.

[10] NGDPs.

[11] Material supplied by Niamh O’Sullivan, Archivist, Kilmainham Gaol, where many of the autographs are held.

[12] This extract is taken from Dorothy Macardle, The Kilmainham Tortures, courtesy of Kilmainham Gaol Archives. There is also a script in the National Library of Ireland headed ‘Farewell to Kilmainham’ by Dorothy Macardle which is almost the same but there are very slight, insignificant word differences in the last few lines of these accounts. The author is grateful to the National Library for providing her with a copy of this account.

[13]Ibid.

[14]Ibid.

[15] National Archives, ref. no. NA 999/951, pp. 110–13.

[16] Courtesy of Niamh O’Sullivan, Archivist, Kilmainham Gaol.