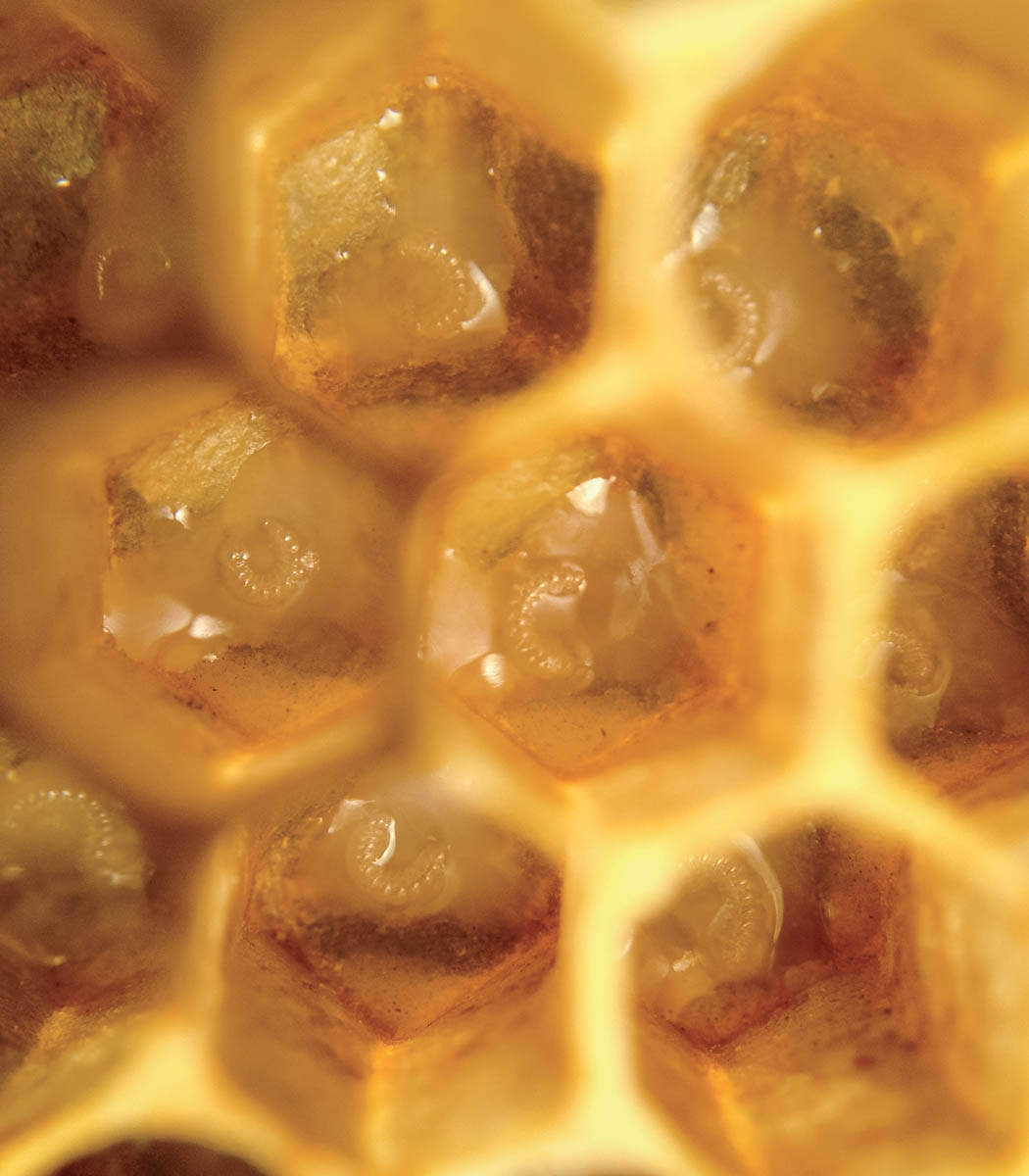

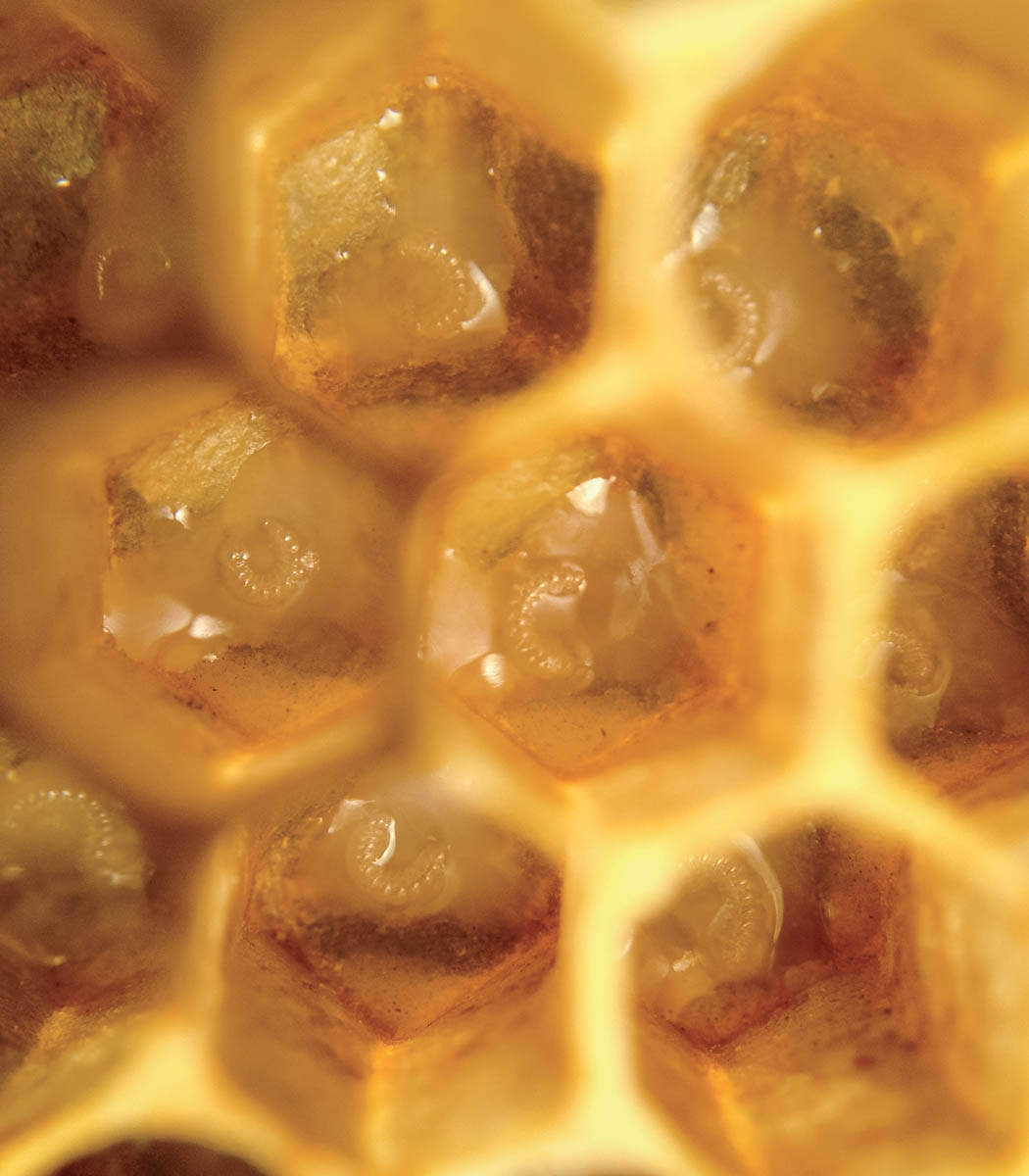

Young larvae ideal for grafting

When left to their own devices, honey bees in the wild don’t always exhibit the traits preferred by beekeepers. Some colonies prioritize raising brood over honey production and will swarm often. Some colonies are extra-defensive or produce an excessive amount of propolis, making them more difficult to manage.

It’s no surprise, then, that beekeepers endeavor to control these behaviors through the selective breeding of queens. Ancient Grecian beekeepers knew how to stimulate queen production, but they did so simply and with little understanding of honey bee biology. It wasn’t until the late 1800s that beekeepers began to develop more advanced methods of queen rearing.

Young larvae ideal for grafting

Although queens are easily made by moving a frame of young brood comb from a colony that has a queen (a queen-right colony) to a queenless colony, modern queen breeding usually involves a technique called grafting.

First the beekeeper selects larvae that are between 12 and 24 hours old from a strong colony with desirable traits. A small tool is used to carefully scoop each larva from its cell into an artificial queen cup of plastic or beeswax. At this stage, the larvae are so tiny you can barely see them with your naked eye. It takes careful skill to move a larva without damaging it, but some beekeepers are so practiced they can do so with only a blade of grass for scooping.

Once the queen cups are full, the beekeeper installs them into what is called a starter colony. These colonies are queenless, well-fed, and packed with young bees that are best able to make royal jelly. The worker bees quickly attend to the future queens, eagerly filling the queen cups with copious amounts of royal jelly.

The queen cells are kept in these colonies only for 24 hours. Then they are moved into a finishing colony, a strong, queenright hive used to care for the queen cells until they are capped. The worker bees inside are attracted to the scent of the queen larvae and will readily attend them. They must travel through a special fixture called a queen excluder, a screen of carefully spaced metal wires that allows the passage of workers but not queens, before they can reach the queen larvae in need.

If a queen excluder is not used to keep the reigning queen separate from the queen cells, she may decide they are a threat to her position and destroy them.

A queen breeder must take careful notes and keep to a strict schedule. Queen cells should be moved from their finishing colony to individual mating colonies 7 to 10 days from when they were grafted, depending on the weather. If a breeder does not time things correctly, he or she could lose all the queens to one tenacious, early-emerging virgin. Imagine the chaos should a queen hatch from her cell ahead of schedule. With all her competitors lined up neatly, still in their cells, she could easily dispose of them all.

A drone yard, used for flooding mating areas with drones

Queen cells being drawn in a finishing colony

A mating colony is usually a very small colony designed to house the new queen temporarily while she mates and begins to lay her first eggs. These miniature colonies receive the queen when she is still in her cell and care for her during her first few weeks of life. During this time, she must mate.

Given that each queen mates with 12 to 20 drones, the local drone population is insufficient for most commercial queen breeding operations. Some breeders avoid this issue by artificially inseminating their queens, but the process is labor-intensive, and these queens tend to perform poorly when compared with naturally mated queens.

For these reasons, breeders often prefer to let their queens mate naturally. Drone yards are set up 1 to 2 miles from the mating colonies where newly emerged virgin queens are preparing to fly. These yards contain drone-producing colonies with desirable traits and are designed to flood the area with eligible males.

After the queen has successfully returned from her mating flight, it is important that the queen breeder allow her to lay for at least 2 continuous weeks because her ovaries are still developing during this time. Once the laying queen has matured, she is deftly caught, marked, and caged for sale. I was once lucky enough to observe this part of the process with a local queen breeder; see The Experts.

A mini frame from a mating colony

Searching for queens

Beekeepers tend to have the best success with queens who are bred in their area because they are already adapted to the climate, but if a queen cannot be purchased locally, many queen breeders ship their queens to customers in the mail. A new queen may travel from one side of the United States to the other before joining a new colony!

I still find it amusing when the mailwoman hands me my buzzing envelope marked red with the caution LIVE BEES. Inside the envelope, the queen is secured in a plastic or wooden cage along with several worker bees who care for her during transport. The bees sustain themselves on a sugar candy plug that also serves to delay their release into the hive. The candy blocks the exit from the cage and it takes the bees several days to eat through it.

A new queen must be introduced gradually, kept in her protective cage while the colony adjusts to her scent. If the queen were released directly, it is likely that the bees would perceive her to be a foreign invader and kill her.

A caged queen