1

What is depression?

If you suffer from depression, you are, sadly, far from being alone. In fact, it has been estimated that there may be over 350 million people in the world today who have it. Depression has afflicted humans for as long as records have been kept. Indeed, it was first named as a condition about 2,400 years ago by the famous ancient Greek doctor Hippocrates, who called it ‘melancholia’. It is also worth noting that although we cannot ask animals how they feel, it is likely that they also have the capacity to feel depressed: they can certainly behave as if they do. To a greater or lesser degree, we all have the potential to become depressed, just as we all have the potential to become anxious, to grieve or to fall in love.

Depression is no respecter of status or fortune. Indeed, many famous people throughout history have had it. King Solomon, Abraham Lincoln, Winston Churchill and the Finnish composer Jean Sibelius are well-known examples from history. What is important to remember is that depression is not about human weakness.

What do we mean by ‘depression’?

This is a difficult question to answer, because a lot depends on who you ask. The word itself can be used to describe a type of weather, a fall in the stock market, a hollow in the ground and, of course, our moods. It comes from the Latin deprimere, meaning to ‘press down’. The term was first applied to a mood state in the seventeenth century.

If you suffer from depression, one thing you will know is that it is far more than just feeling ‘down’. In fact, depression affects not only how we feel, but how we think about things, our energy levels, our concentration, our sleep, even our interest in sex. Depression has an effect on many aspects of our lives. Let’s look at some of these.

Motivation. Depression affects our motivation to do things. We can feel apathetic and experience a loss of energy and interest, nothing seems worth doing. If we have children, we can lose interest in them and then feel guilty. Each day can be a struggle of having to force ourselves to perform even the smallest of activities. Some depressed people lose interest in things. Others keep their interest but don’t enjoy things when they do them, or are just very tired and lack the energy to do the things they would like to do.

Emotions. People often think that depression is only about low mood or feeling fed-up – and this is certainly part of it. Indeed, the central symptom of depression is called ‘anhedonia’– derived from the ancient Greek meaning ‘without pleasure’– and means the loss of the capacity to experience any pleasure. Life seems empty; we are joyless. But – and this is an important ‘but’ – although the ability to have positive feelings and emotions is reduced, we can experience an increase in negative emotions, especially anger. We may be churning inside with anger and resentment that we can’t express. We might become extremely irritable, snap at our children and relatives and sometimes even lash out at them. We may then feel guilty about this, and this makes us more depressed. Other very common symptoms are anxiety and fear. When we are depressed, we can feel extremely vulnerable. Things that we may have done easily before seem frightening, and at times it is difficult to know why. We can suddenly feel anxious at a bus or shop queue or even meeting friends. Anger and anxiety are very much part of depression. Other negative feelings that can increase in depression are sadness, guilt, shame, envy and jealousy.

Thinking. Depression interferes with the way we think in two ways. First, it affects concentration and memory. We find that we can’t get our minds to settle on anything. Reading a book or watching television becomes impossible. We don’t remember things too well, and we are prone to forget things. However, it is easier to remember negative things than positive things. The second way that depression affects our thoughts is in the way we think about ourselves, our future and the world. Very few people who are depressed feel good about themselves. Generally, they tend to see themselves as inferior, flawed, bad or worthless. If you ask a depressed person about their future, they are likely to respond with: ‘What future?’ The future seems dark, a blank or a never-ending cycle of defeat and losses. Like many strong emotions, depression pushes us to more extreme forms of thinking. Our thoughts become ‘all or nothing’ – we are either a complete success or an abject failure.

Images. When we are depressed, the imagery we use to describe it tends to be dark. We may talk about being under a dark cloud, in a deep hole or pit, or a dark room. Winston Churchill called his depression his ‘black dog’. The imagery of depression is always about darkness, being stuck somewhere and not able to get out. If you were to paint a picture of your depression, it would probably involve dark or harsh colours rather than light, soft ones. Darkness and entrapment are key internal images.

Behaviors. Our behavior changes when we become depressed. We engage in much less positive activity and may withdraw socially and want to hide away. Many of the things we might have enjoyed doing before becoming depressed now seem like an ordeal. Because everything seems to take so much effort, we do much less than we used to. Our behavior towards other people can change, too. We tend to do fewer positive things with others and are more likely to find ourselves in conflict with them. If we become very anxious, we might also start to avoid meeting people or lose our social confidence. Depressed people sometimes become agitated and find it difficult to relax. They feel like trapped animals, restless, pace about and can’t sit still, wanting to do something but not knowing what. Sometimes, the desire to escape and run away can be very strong. However, where to go and what to do is unclear. On the other hand, some depressed people become very slowed down. They walk slowly, with a stoop, their thoughts seem stuck, and everything feels ‘heavy’.

Physiology. When we are depressed there are many changes in our bodies and brains. There is nothing sinister about this. To say that our brains work differently when we are depressed is really to state the obvious. Indeed, any mental state, be it a happy, sexual, excited, anxious or depressed one, will be associated with physical changes in our brains. Recent research has shown that some of these are related to stress hormones such as cortisol, which indicates that depression involves the body’s stress system. Certain brain chemicals, called neurotransmitters, are also affected. Generally, there are fewer of these chemicals in the brain when we are depressed, and this is why some people find benefit from drugs that allow them to build up. The next chapters will explore these more fully. Probably as a result of the physical changes that occur in depression, we can experience a host of other unwanted symptoms. Not only are energy levels affected, so is sleep. You may wake up early, sometimes in the middle of the night or early morning, or you may find it difficult to get to sleep, although some depressed people sleep more. In addition, losing your appetite is quite common and food may start to taste like cardboard, so some depressed people lose weight. Others may eat more and put on weight.

Social relationships. Even though we may try to hide our depression, it almost always affects other people. We are less fun to be with. We can be irritable and find ourselves continually saying no. The key thing here is that this is quite common and has been since humans first felt depressed. We need to acknowledge these feelings and not feel ashamed about them. Feeling ashamed can make us more depressed. There are various reasons why our relationships might suffer. There may be conflicts that we feel unable to sort out. There may be unvoiced resentments. We may feel out of control. Our friends and partners may not understand what has happened to us. Remember the old saying, ‘Laugh and the world laughs with you. Cry and you cry alone’? Depression is difficult for others to comprehend at times.

Brain states. A useful way to think of depression, then, is that it is a change in ‘brain states’. In this altered state, many thing are happening to your energy levels, feelings, thoughts and body rhythms. There are many reasons for this change in brain state that we call depression, and there are many different patterns that are linked to depression, as we will see. But the key thing is to recognize there has been a change in brain state, and your thoughts and feelings are linked to that. It is very important not to blame yourself for the difficulties that this depressed brain state makes for you, but rather work out what will help you shift it – and that is what we will be exploring in this book.

Are all depressions the same?

The short answer to this is no. There are a number of different types. One that researchers and professionals commonly refer to is called ‘major depression’. According to the American Psychiatric Association, one can be said to have major depression if one has at least five of the possible symptoms listed in Table 1.1, which have to be present for at least two weeks.

I have included this list of symptoms here to give you an idea of how some professionals tend to think about depression. Although a list like the one in Table 1.1 is important to professionals, it does not really capture the variety and complexity of the experience of depression. For example, I would include feelings of being trapped as a common depressed symptom, and many psychologists feel that hopelessness, irritability, and anxiety are also very central to depression.

TABLE 1.1 SYMPTOMS OF DEPRESSION

|

You must have one of these symptoms: |

Low mood |

|

|

Marked loss of pleasure |

|

You must have at least four of these symptoms: |

Significant change in appetite and a loss of at least 5 per cent normal body weight |

|

|

Sleep disturbance |

|

|

Agitation or feelings of being slowed down |

|

|

Loss of energy or feeling fatigued virtually every day |

|

|

Feelings of worthlessness, low self-esteem, tendency to |

|

|

feel guilty |

|

|

Loss of the ability to concentrate |

|

|

Thoughts of death and suicide |

Researchers distinguish between those mental conditions that involve only depression and those that also involve swings into mania. In the manic state, a person can feel enormously energetic, confident and full of their own self-importance, and may have great interest in sex. If the mania is not too severe, they can accomplish a lot. People who have swings into depression and (hypo)mania are often diagnosed as suffering from bipolar illness (meaning that they can swing to both poles of mood, high and low). The old term was manic depression. Those who only suffer depression are diagnosed as having unipolar depression.

Another distinction that some researchers and professionals make is between psychotic and neurotic depression. In psychotic depression, the person has various false beliefs called delusions. For example, a person without any physical illness might come to believe that he or she has a serious cancer and will shortly die. Some years ago, one of my patients was admitted to hospital because she had been contacting lawyers and undertakers to arrange her will and her funeral as she was sure that she would die before Christmas. She believed that the hospital staff were keeping this important information from her to avoid upsetting her, and she tried to advise her young children on how they should cope without her (causing great distress to the family of course). Sometimes people with a psychotic illness can develop extreme feelings of guilt. For example, they may be certain in their minds they have caused the Iraq war, or done something terrible. Psychotic depression is obviously a very serious disorder, requiring expert help but, compared with the non-psychotic depressions, it is quite rare.

Another distinction that is sometimes made is between those depressions that seem to come out of the blue and those that are related to life events, e.g., when people become depressed after losing a job, the death of a loved one or the ending of an important relationship. However, in psychotherapy, we often find that, as we get to know a person in depth, what looks like a depression that came out of the blue actually may have its seeds in childhood.

Clearly some depressions are more serious, deep and debilitating than others. In many cases, depressed people manage to keep going until the depression eventually passes. In more serious depression this is extremely difficult, and getting professional help is important. Depressions can vary in terms of onset, severity, duration and frequency.

Onset. Depression can have an acute onset (i.e. within days or weeks) or come on gradually (over months or years). It can begin at any time, but late adolescence, early adulthood and later life are particularly vulnerable times.

Severity. Symptoms may be mild, moderate or severe.

Duration. Some people will come out of their depression within weeks or months, whereas for others it may last in a fluctuating, chronic form for many years. ‘Chronic depression’ is said to last longer than two years, and 10–20 per cent of depressed people have it.

Frequency. Some people may only have one episode of depression, whereas others may have many. About 50 per cent of people who have been depressed will have a recurrence.

The fact that depression can recur may seem alarming, but this should really come as no surprise. Suppose, for example, that since a young age you have always felt inferior and worthless. One day this sense of inferiority seems to get the better of you and you feel a complete failure in every aspect of your life. Perhaps a drug will help you to recover from that episode, but even if you become better, you may still retain, deep down, those feelings of failure and inferiority. Drugs do not retrain us or enable us to mature and throw off these underlying beliefs. Therapies are now being developed to help prevent relapses.

How common is depression?

As indicated, depression is, sadly, very common. If we look at what is called major depression, the figures are:

|

|

Women |

Men |

|

|

|

(per cent) |

||

|

Having depression at any one time |

4–10 |

2–3.5 |

|

|

Lifetime risk |

10–26 |

5–12 |

|

The figures are even higher in some communities (e.g., with poverty). Moreover problems such as eating disorders, drug and alcohol problems and aggressiveness can also be linked to de pression, and recede as depression is treated. New research also indicates that rates of and risks for depression have been steadily increasing throughout the twentieth century, but the reasons for this are unclear. Socio-economic changes, the fragmentation of families and communities, the loss of hope in the younger generation – especially the unemployed – and increasing levels of expectations may all be implicated.

In general, then, there are many forms of depression – in fact, so many that the term itself is not so helpful. But it is important to recognize that not all depressions are the same and they can vary greatly in severity and duration.

KEY POINTS

Depression is very common and has been for thousands of years.

Depression involves many different symptoms. Emotions such as anger and anxiety are common and at times more troubling than the low mood itself. People who are depressed may also have a strong desire to escape, for which they may feel guilty.

There are many different types of depression.

Some depressions are quite severe, while others are less so but still deeply disturbing and life-crippling.

If you suffer from depression, my key message to you is that if you feel a failure, if you have a lot of anger inside, feel on a short fuse; if you are terrified out of your wits, if you think life is not worth living, if you feel trapped and desperate to escape – whatever your feelings – these reflect your brain state, are not your fault, and millions of others have these feelings too. Of course, knowing this does not make your depression any less painful, but it does mean that there is nothing bad about you because you are in this state of mind. It is a shift in brain state that is painful – depression pulls us into thinking and feeling like this, so these feelings are sadly part of being depressed. True, some people who have not been depressed may not understand it, or may tell you to pull yourself together, but this does not mean that there is anything bad about you. It just means that they find it difficult to understand.

Importantly, there are many things that can be done to help us when we get depressed so a key message is: ‘please talk to your family doctor.’ There are some helpful (for some people) drugs (anti-depressants) available and many effective psychological treatments. We can learn to train our minds to shift us out of depressed brain states. This is covered in Parts II and III.

2

Causes of depression:

How and why it happens

As we saw in Chapter 1, when we are depressed our brains, bodies and minds shift to different patterns of thinking, feeling and behaving. We can call this a depressed brain or mind state. A key question, then, is how and why this happens. After all, these depressed states are very unpleasant and don’t seem very helpful in our lives. Understanding why our brains can go into depressed patterns is a key research question. In the next few chapters we are going to explore this.

If you’re feeling depressed, you may find these chapters tough going at times because they contain technical information, and it can be difficult to concentrate when you are depressed. Please don’t worry about that. You don’t need to read these sections if you don’t want to, and even if you do read them it is quite likely that you may only remember one or two key ideas, so there is a summary at the end of each chapter. If you wish, just note those key points and go straight on to Part II, ‘Learning How to Cope’. When you feel better, you could return to these chapters, or dip into them. I have expanded them from the first and second editions because depressed people and their relatives often ask to know more about what causes depression. I have also expanded them to explain a new focus on compassion. Being gentle with ourselves will be helpful in our journey out of depression.

How our minds got to be the way they are: old brains and new minds

Old brain and mind – what we share with other animals

It is very easy for us humans to see ourselves as special and different from other animals because we have a certain self-awareness and recently evolved abilities to think, reflect, plan and ruminate – with a kind of ‘new mind’. But even though this is true we also have many motives, emotions and social needs in common because of how our brains have evolved and are constructed. For example, animals (e.g., chimpanzees) can become anxious, angry, lustful, vengeful, sad, distressed, agitated or excited, happy, playful, and affectionate. Like us, too, they seek out certain positive things such as food and comforts, and create certain types of relationships. They can fight with each other over status or territory; they can seek each other out for protection, support and friendships; they can form close bonds; they can develop sexual relationships, and can be very attached to their offspring, protecting them, nurturing them and providing for them. Like us, too, they appear to become stressed and depressed if they are socially rejected, defeated or threatened. Indeed, we see these desires, encounters and relationships going on in their billions in many life forms on this planet every day.

We too are constantly engaging in these behaviors. From the day we are born we seek a loving and caring attachment with our parents. We can struggle for status, recognition and acceptance from other human beings. We want to form relationships with others who care about us and help us. We feel good when relationships go our way. We don’t want to be criticized or rejected: then we can get sad, upset or angry. When things go wrong and we feel unable to achieve these desired goals, and/or we feel unloved, or rejected and inferior, our mood can go down, as it can for any other animal.

We can call all these forms of behavior, with their various desires and efforts, archetypes because they are forms of feeling and thinking that ripple through many life forms, including us. They give rise to our feelings and desires. Look at this carefully:

We did not create these desires for certain types of relationship and feelings – rather, they are created within us, from our genes and our evolutionary history and are shaped by our life experience.

The point is that we all just find ourselves with this body, with this mind with its varieties of emotions, born into particular families in particular places at particular times – none of which we choose. We sort of ‘wake up’ through our childhood to the fact of us ‘being here’ and then try to make the best we can of this strange mind of ours. So, much of what goes on in our minds is not our fault – evolution put these abilities there but, by understanding how our minds work, we can learn how better to cope with unpleasant feelings that can ripple through us, and train our minds to cope. We can influence how our brains are working and steer them towards feelings of well-being and away from depression.

The three emotion systems and their influence on our minds

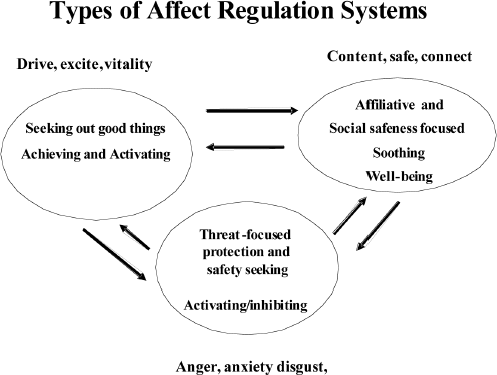

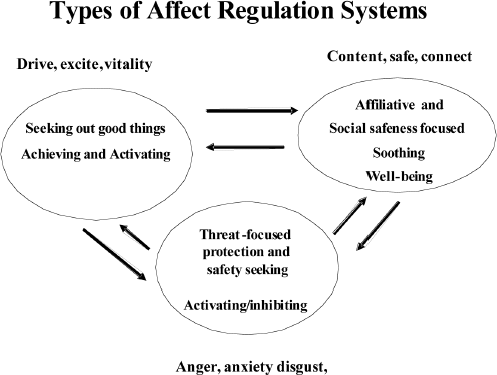

Let’s now look a little closer at how the brain helps us navigate through life, noticing and trying to avoid threats, seeking out things we want, and influencing our feelings in our relationships. The way the brain does this is very complex but we can simplify it in a very useful way. We have special brain systems (networks) that regulate three different types of emotion and action:

a system that helps detect, track and respond to things that threaten us

a system that gives rise to desires and feelings of motivation

a system that helps us feel content, at peace, safe and happy. This system is especially important in social relationships when we feel cared for.1

These systems are constantly interacting and it is from their interactions that we get ‘states of mind’. Figure 2.1 is a diagram of these interacting systems.

Figure 2.1 The interaction between our three major emotion regulation systems.

As we become depressed the balance between these systems changes and we have far more threat-linked feelings of anxiety, irritability, pessimism, shame and anger, far fewer feelings of motivation, energy and optimism, and also far fewer feelings of contentment, peacefulness and sense of connectedness to other people. It is helpful to understand this in terms of a shift in the balance of feeling and thinking systems. Then we can stand back from the depression and recognize that it is a particular pattern in our brains that we are having to deal with. The reasons these brain systems have become out of balance, or have taken up a new pattern, will be the subject of later chapters.

Thinking about depression in this way gives us an opportunity to think about how we can rebalance the three emotion systems. If you like, we can think about working on ourselves as a kind of physiotherapy for our minds. In the second half of this book we will explore how we can rebalance our systems by working on our behaviors, thoughts and feelings. Exercise, diet and medication may also help, but they are not the main focus of this book (see the appendices for some thoughts on these). Next we explore these three emotion regulation systems in more detail.

The threat-protection and safety-seeking system

Life on our planet faces a variety of dangers, from other life forms that want to eat them, fights with others of their own kind, lack of food or shelter, to viruses, bacteria and so on. Because life forms face so many threats, they need to have systems in their brains that can detect them and respond.2

We can call this the threat-protection and safety-seeking system, or threat-protection system for short. It is designed to detect threats, activate protective emotions such as anxiety and start behaviors that will help us to keep safe, such as running away or avoiding things. In humans and other animals this system can be activated very quickly, giving rise to feelings of anxiety, anger or disgust, with their associated behaviors for fighting, running away, and trying to get rid of things. Note too that we can have these feelings if we see others – especially those we love – in danger or distress: we want to rush in to protect them.

Although this system was developed for our protection, many of the emotions, feelings and thoughts associated with it can cause us problems and indeed underpin many mental health difficulties. For example, our anxiety or anger can become too easily triggered or too intense, or difficult to turn off. We might become anxious about situations we don’t want to be anxious about – such as standing in a queue, going to a party or job interview. Our emotional brain and our logical (new) brain seem to be saying rather different things. When we experience our emotions getting in the way of what we can logically want to do or feel, we tend to see such feelings as ‘bad’ and ‘to be got rid of’, but in fact they are only designed as self-protection. It is often because we don’t understand that they are part of our alarm and self-protection system that we can have such a negative approach to these emotions. When this happens we tend to fight with them, avoid them or even come to hate them rather than work with them.

Our new brains may focus thinking and rumination on threat and losses. The last time I had to take an important exam I found it difficult not to think about it, or to sleep well the night before. That can be useful, of course, because I prepared well (I hope). After the exam I started going back in my mind over what I had written and wondering if I had answered questions correctly or sufficiently, oscillating between confidence and doubt. That is how our minds are, worrying about the future and reflecting on the past. Sometimes focusing on threat and preparing for it is very helpful. However, feeling one’s mind constantly pulled to focus on a threat or loss can be very unhelpful. Then we worry and fret about things, and at times we give up trying altogether, anticipating that it will go badly – so we feel there is no point.

Depression as a threat-protection response

Many researchers are now looking at depression from an evolutionary point of view.3 Research has shown that when we are depressed, an area of the brain (called the amygdala) that is associated with detecting and responding to threats seems to become more sensitive.4 Indeed, some depressed people can have greatly increased anxiety and/or anger and irritability because the threat system has become ‘inflamed’, if you like. This may be linked to threat in our current situation, genetic sensitivity, unresolved anger or anxiety issues from the past, or other reasons, but it is useful to think about some aspects of a depression being linked to this physiological sensitivity in our threat-protection system. We can then consider how to work on reducing this sensitivity and help to settle it down.

The situations that can trigger depressive changes in our brains are linked to particular difficulties, and we will be looking at these in the next two chapters. Situations that are important to us but where we feel we have lost control, or we feel no matter how much we try we can’t reach our goals, or we feel overwhelmed by demands on us, or we find ourselves trapped in situations we don’t want to be in (e.g., isolated, or with critical or unkind others), or feeling defeated or exhausted – can all contribute to depression. Feeling isolated, alone, misunderstood, or unlovable and cut off from others is also strongly linked to depression. Depression is a kind of shutdown, a ‘go to the back of the cave and stay there until things improve’ response.

The feel-good emotions

Depression is not just about having more anxiety and irritability. A key element of depression is that positive emotion systems seemed to be toned down too. We are not able to enjoy things or look forward to things. Things we used to enjoy, such as talking to people, going to parties, planning a holiday or even having sex can become things that are actually unpleasant to do; they fill us with dread and we can see nothing but problems and difficulties in doing them. In fact, although feeling accepted and connected to others is associated with feelings of well-being, when we are depressed we often feel disconnected from other people, as if there is a barrier between us and others, almost as if we are an outsider or an alien. This tells us that positive emotion systems in our brain are toned down. So to help us out of depression we have to practise stimulating our positive emotion systems, to get them active in our brains again.

Recent research has shown that there are in fact two very different types of positive feeling and emotion systems (see page 17).1 One type is linked to a system that is activating and energizing; it is the system that gives rise to desires, and the buzz of excitement if something good happens to us or to people we care about, or even if our football team wins. It energizes us. This emotion system helps us to become active, to seek out good things, and to try to achieve and acquire things in life – it gives us certain feelings and drive.

The other positive emotion system is almost the opposite; it’s not about achieving but about being safe and at peace. It is soothing and calming and gives feelings of contentment and well-being. It is the system that people who meditate try to stimulate.

These two systems evolved over millions of years. Let’s look at them a little more closely.

The activating system

This system motivates us to achieve things and do things. It gives rise to our wants, and our desires to satisfy these. When good things happen, we can also get a buzz from this system. For example, if you win the lottery tonight and become a millionaire you may have bursts of excitement and become agitated; your mind will be churning with thoughts of your future; you’ll find it difficult to stop smiling and you may also find it difficult to sleep because your mind will be racing. This is the system that can become overactive in people who have bipolar dis order. But if you are very depressed, even winning the lottery might wash over you because your positive emotion system only gives a slight splutter and you quickly get pulled back into the threat system, dwelling on all the problems having money will bring – how much to give to Uncle Tom and Aunty Betty and what happens if you upset cousin Alfred – what’s the point of money anyway if it makes you feel this bad?

Of course, usually the drive system is not nearly as highly activated as this but it gives us our little bursts of energy and excitement. If we are overstressed or push ourselves too hard, this system can get exhausted, and we can start to lose feelings of motivation and interest in things. We start to feel that we can’t be bothered; even deciding what to have for lunch is boring and we can’t think of anything we fancy. We find, as the Rolling Stones once wrote, that we ‘can’t get no satisfaction’.

There are many ways in which the drive system can become exhausted. If we overwork and become very tired the system can start to struggle; it runs out of fuel because we’ve been over using it. If we are under a lot of stress for a long time, this again can affect our positive emotion system and we lose energy and motivation. Feeling helpless and out of control can cause the system to become exhausted. If we are being bullied or criticized at home or work, or if we are in a conflict relationship, or if we are very divided on what to do, whether to stay in this job or relationship or leave – these stressors can gradually tone down the drive system.

So when we are depressed it is useful to think about whether this system has become exhausted and, if so, how we can start to heal it, exploring what it needs to get up and running again. If you are self-critical for being depressed or tired, then this is only going to exhaust the drive system even more. Self-criticism does not – under any circumstances – increase enthusiasm, motivation or pleasure. It motivates through threatening and a fear of failure – that is, through your threat system. Sometimes we have to work hard to become more active and put positive things in our lives as best we can. This can mean deliberately training our attention to focus on positive things – things we appreciate, no matter how small – such as the taste of your first cup of tea in the morning, or the smile of a friend. If we recognize that we have a particular problem in a particular system in our brain then we can design a program to get it going again. Taking exercise can help stimulate this system too.

Useful and important as the drive system is, there are signs that Western society is rather overstimulating it and leading us to believe that we can only be happy if we have and achieve things. This leads people to constantly compare themselves with others, to reflect negatively on themselves – and that’s pretty depressing, because it takes away enthusiasm and hope of success. We are also overworking and getting exhausted in the drive for the ‘competitive edge’ or proving ourselves competent.

Contentment, soothing and kindness

How does kindness fit into feelings of depression and a lack of well-being? Well, it does so in some very interesting ways. First, we should note that in our brains we have a system that regulates the experience of ‘having sufficient, enough, and contentment’. When animals are not dealing with threats, and are not having to pursue things like food or other resources, they can be quiet, resting, quiescent and peaceful. We now know that this state is not just about low activity in the threat system. There is a system in our brain that gives us feelings of contentment where we are not seeking or feeling driven to achieve things – we are happy as we are, right now, in this moment. Think back to times you might have had feelings of contentment, being satisfied with where you were. People who meditate and become mindful (see Chapter 7) and spend time trying to develop calm states of mind often describe positive feelings of contentment, well-being and peacefulness.

But what has this got to do with kindness? To understand this you need to know that the evolution of our brains and bodies always uses systems that already exist. It is very difficult for evolution to design something totally new. The system that gives us our feelings of peacefulness, calmness and soothing is also linked to affection and being cared for. How did that happen? Simply put, millions of years ago the young of our mammal ancestors that were fed and protected survived and so passed on the genes for care and protection. Over millions of years these spread throughout the world. Today, whether you look at birds looking after their chicks in the nest, your family dog looking after her pups, monkeys caring for their infants or humans loving their babies, we see the enormous importance of love and affection in the process of protecting and caring. If you look carefully at these interactions you will also see something very interesting. When in close contact with its mother, the young infant is often peaceful and quiet.5 An extreme example is the emperor penguin, where the baby chick has to sit on the parent’s feet and not move or it will freeze.

What do caring relationships do to and for the child? First, they turn off the child’s threat system. Indeed, think how a mother is often able to calm and soothe a distressed infant. Through the mother’s tone of voice, or cuddling and gentle soothing, the child’s brain registers that it is being looked after and this calms the threat system. This ability to soothe distress with kindness is fundamental to how our brains work. It is part of our evolutionary design. Our brains are designed to want kindness, and can respond to kindness. And it’s not only in child–parent relationships that kindness is powerful. Kindness is one of the most important qualities that people look for in a long-term partner; it’s one of the most important qualities people look for in friendship and (along with technical ability of course) one of the most important qualities we look for in our doctors, nurses, teachers and psychotherapists. We may not always be good at giving it, and sometimes we can be grumpy toads – but humans value and look for kindness because their brains are organized to feel more secure and safe in the context of kindness.

To help you think about how kindness operates in the body, consider the following scenario. You are upset about something: maybe a project you were planning hasn’t worked out, or you are very disappointed over something, or someone you spoke to was unkind. Imagine you go to a friend, but they are very dismissive or they quickly switch the conversation around to their own difficulties, or are even critical of you and tell you to stop making mountains out of molehills. How will you feel. How will you feel in your body? Think about that. Now imagine you go to a friend who listens very carefully to your story. They sympathize and empathize with your upset, they say how they can understand why you are upset. Maybe they put an arm on your shoulder. How do you feel? You see, you already know in your heart that kindness will have a very different impact on your body. You have inner wisdom on the value of kindness and can learn to tune into it rather than getting caught up in the angers, frustrations, disappointment and fears of your threat system. As we will see in a moment, this is also the case for our own self-focused thoughts and attitudes to ourselves – these too can be rather bullying, but we can train them to be kind and supportive.

Kindness is important, too, because it underpins trust. When we trust people we are no longer orientated by threat, nor are we striving to impress them. We can turn to them if we need to. In a way kindness and trust can also tone down aspects of our drive and threat-protection systems and bring them more into balance. This is important to understand, because sometimes people who are vulnerable to depression feel they have to drive themselves hard, to impress others or to be liked and accepted. The drive system gets out of balance because of feeling insecure with other people, which means that the soothing system requires some development. We will be looking at exercises to help you with this later.

Without going into too much detail, these kinds of emotions use different chemicals in our brains, in different patterns to those of excitement and achievements.1 These calm, good feelings of well-being are linked to endorphins (the body’s natural opiates) and a hormone called oxytocin. This hormone has generated a lot of interest recently because it is linked to feelings of closeness and trust with other people, and the warm feelings we get from affiliation and affection.5

Problems with our new minds

Our thoughts can also affect how these systems work and balance each other. Over the past two million years or so the human brain has been evolving abilities to think, to imagine, to predict, to ruminate and plan. We can form mental images in our minds. We can imagine the future, and think about how we can create a future that we want (or feel trapped in one we don’t want). Much of our life is spent thinking about and planning for our wants; generating hopes, planning for our future, developing goals and worrying about obstacles and setbacks. Animals simply live out their lives, but humans are life planners and try to live according to their plans. This thinking gets pretty sophisticated. Indeed, it is because we can think like this that we have an intelligence that underpins science and technology. Our ability to imagine, think and plan with some complexity is central to the human mind.

As we will see later though, what we focus and think about, and how we focus our attention and thinking, can seriously affect our moods. Monkeys don’t worry about being able to pay the mortgage, or failing a job interview, nor how to get out of a marriage; nor do they ruminate about feeling depressed in the future. Humans clearly do, though, and this can be one reason for low mood.

We also have a complex language, can talk to each other and can share wonderful ideas and feelings. We can share and build our plans and goals together. We can use symbols that help us to think. We have also evolved a sense of self-awareness. We have an awareness of being ‘alive’, being a self with a consciousness. These are wonderful abilities and give rise to our science, art and culture. We create and follow fashion because we have a sense of ourselves and how we wish to appear to others. We can create a sense of self-identity and this varies according to where we live. Think how different our self-identity would be if we grew up in a Buddhist monastery, in the backwoods of Alaska, in glitzy Hollywood or in a poor inner-city area.

However, there is a downside to these wonderful new mind abilities, because if our thinking about ourselves or future becomes overly threat- or loss-focused then we can lock ourselves into threat-process thinking and some very unpleasant feelings indeed.

How our thoughts and imaginations affect our brains

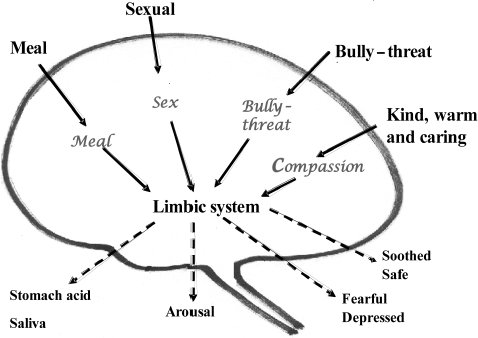

To help you explore how thoughts, images and memories can have powerful effects on systems in our brains, look at the brain depicted in Figure 2.2. It demonstrates how external things and our imagination of external things can work in a very similar way. Let’s start by using examples that I commonly use and have discussed on my CD Overcoming Depression: Talks With Your Therapist.

Figure 2.2 The way our thoughts and images affect our brains and bodies.

Imagine that you are very hungry and you see a lovely meal set out on a table. What happens in your body? The sight of the meal stimulates an area of your brain that sends messages to your body so that your mouth starts to water and your stomach acids get going. Spend a moment really thinking about that. Now suppose that you’re very hungry but there isn’t any food in the house, so you close your eyes and imagine a wonderful meal. What happens in your body then? Again, spend a moment really thinking about that. Well, those images that you deliberately create in your mind can also send messages to parts of your brain that send messages to your body, so again your mouth will water and your stomach acids will get going. Remember though, this time there is no meal: it’s only an image that you’ve created in your mind, yet that image is capable of stimulating those physiological systems in your body that make your saliva flow. Take a moment to think about that.

Here’s another example, something that some of us have come across: you see something sexy on TV. This may stimulate an area of your brain that affects your body, leading to arousal. But equally, of course, we know that even if you’re alone in the house you can imagine something sexy and that can affect your body. The reason for this is that the image alone can stimulate physiological systems in your brain in an area called the pituitary, which will release hormones into your body.

The point is that thoughts and images are very powerful ways of stimulating reactions in our brain and our body. Take a moment and really think about that, because this insight will link to other ideas to come. Images that you deliberately create in your mind and your thinking will stimulate your physiology and body systems.

Let’s consider a more depression-linked example. Suppose someone is bullying you. They are always pointing out your mistakes or dwelling on things you are unhappy with, or telling you that you are no good and there is no point in you trying anything, or being angry with you. This will affect your threat-protection and stress systems. How do you feel if people criticize you? How does it feel in your body? Spend a moment thinking about this. Their unpleasantness will make you feel anxious, upset and unhappy because the threat emotion systems in your brain have been triggered. If the criticism is harsh and constant, it may make you feel depressed. You probably would not be surprised by that. However, as we have suggested, and here is the point – our own thoughts and images can do the same. If you are constantly putting yourself down this can also activate your stress systems and trigger the emotional systems in your brain that lead to feeling anxious, angry and down. That’s right – our own thoughts can affect parts of our brain that give rise to more stressful and unpleasant feelings. They can certainly tone down positive feelings. Who ever had a feeling of joy, happiness, contentment or well-being from being criticized? If we develop a self-critical style then we are constantly stimulating our threat system and will understandably feel constantly under threat. Self-criticism then stimulates the threat system. This is no different from saying that sexual thoughts and feelings will stimulate your sexual system, and the thoughts of a lovely meal will stimulate your digestive system.

There are many reasons for becoming self-critical. One common reason is that others have been critical of us in the past and we simply accept their views as accurate. We don’t stop to think whether they were genuinely interested in our welfare and really cared and wanted to help us – in fact they may just have been rather stressed and irritable people who were critical of everyone. We have gone along with their criticisms of us – as one often does as a child – and never stopped to think if they are accurate or reasonable. Or it may be that we are trying very hard to reach a certain standard, or to achieve something, or present ourselves in a certain way. When it doesn’t work out as we would like, this can frighten us because we may think we have let ourselves down or other people will reject us. In our frustration we then criticize ourselves and take our frustration out on ourselves. All very understandable, but not helpful, because we are giving ourselves negative signals that affect our brains. Research on what happens in people’s brains when they are self-critical confirms that it really is the case that we stimulate threat systems in our brain. The more self-critical we are, the more those systems are stimulated. Learning to spot self-criticism and what to do about it is a key issue in later chapters.

The power of self-kindness

We have spent some time looking at the three emotion regulation systems and we explored a system in the brain that helps to soothe and calm us when things are hard or we are frightened. We feel soothed when other people are kind and understanding, supportive and encouraging. We have a system in our brains that can respond to those behaviors from others. Suppose that when you are struggling there is someone who cares about you, understands how hard it is, and encourages you with warmth and genuine care – how does that feel? Maybe you could spend some time thinking about this right now. Or imagine that you are learning a new skill and finding it hard; maybe other people seem to be getting the hang of it more easily than you. However, you have a teacher who is very gentle and warm, pays careful attention to where your difficulties are, helps you see what you are doing right and how you can build on those good things. Compare this with a teacher who is clearly irritated by you, makes you feel you’re holding up the class, and focuses on your deficits. Most of us are going to prefer the first type of teacher, and indeed will do much better.

So using exactly the same idea as imagining how a meal can stimulate sensations and feelings in our bodies linked to eating, we can think about how our own thoughts and images might be able to stimulate the kindness and soothing system. If we can learn to be kind and supportive – to send ourselves helpful messages when things are hard for us – we are more likely to stimulate those parts of our brain that respond to kindness. This will help us cope with stress and setbacks. As this book unfolds, you will learn how to engage with compassionate attending, thinking, behavior, imagery and feeling (see Chapter 9). Bear in mind all the time that this is about helping you to re-balance systems in your brain.

What happens in our brains when we focus on self-critical or self-reassuring and self-compassionate feelings? Self-criticism stimulates parts of our brain linked to threat, whereas self-compassion and reassurance stimulates parts of our brain linked to empathy and soothing. However, there is an added complication. For some people who are very self-critical, starting to become self-compassionate can seem like a threat. Some people feel that wanting kindness, or even making an effort to be kind and gentle to oneself, is a weakness or an indulgence. They believe that either they or others simply don’t deserve it. Our research indicates that when people first start to be kind to themselves, they can feel it as rather strange or threatening. They have to work through these ‘fears’ to start training their minds in self-kindness.

Nonetheless, there is now a lot of evidence that being compassionate or kind to yourself is associated with well-being and being able to cope with life stresses. You can read more about this from a leading researcher at www.self-compassion.org.

There are important differences between self-compassion and self-esteem. For example, self-compassion is important when things are difficult or going wrong, and you are having a hard time. Self-esteem, on the other hand, tends to be associated with doing well and achieving. Self-esteem is more linked to our drive-achievement system. It often focuses on how well we are doing in comparison with others, and this is why low self-esteem is often linked to feeling inferior – as we are judging ourselves in comparison with others. Self-compassion, on the other hand, is about focusing on our similarity and shared humanity with others, who also struggle as we do.

Our brains have been designed by evolution to need and to respond positively to kindness, so it is not a question of ‘what we deserve’. It is not self-indulgence, any more than training your body to be fit and healthy is a self-indulgence. It is simple a question of treating our brain wisely and feeding it appropriately. This is really no different from (say) understanding that our body needs certain vitamins and a balanced diet. It’s not a question of whether you deserve to give your body vitamins or not, you simply do it because it’s sensible. It’s the same with kindness. It’s not an issue of deserving, it’s an issue of understanding how our mind works and then practising how to feed it things to help it work optimally. We will be looking at this as we go through the book because some people find this a bit tricky; they can even be frightened to give up their sense of being inadequate or bad in some way. However, they can practise switching to self-kindness each day and see how things go.

Not our fault

I’m sorry if I seem a bit repetitive here, but this is an important idea to convey: ‘depression is not our fault and there is nothing bad about us’. Indeed, evolution may have designed depression (with its reduced positive feelings and increased negative feelings) as a kind of protection when we are in a high-stress environment – like a safety switch or fuse on an electrical circuit that trips out if it is overloaded. The reason for hammering away at this idea is because some depressed people struggle terribly, feeling responsible, inferior or inadequate in some way for being exhausted or depressed. That’s why so many depressed people don’t seek help – because they are ashamed of depression. They may not even recognize it themselves.

If you can take the approach outlined here, you can see that our depressions need our compassionate understanding – to be worked with, worked on and healed as best we can. We did not design any of the mechanisms in our brain that give rise to depression – nor any of the desires that may be thwarted, and cause depression – nor the genes that might make us vulnerable to depression – nor the early life experiences that also make us vulnerable to depression. If we see this, then we also see that depression cannot possibly be our fault.

However, because the depression is happening inside our heads the question is, how can we take responsibility or be ‘response able’ – that is, come up with healing and balancing responses to our depressed brain states? Can we learn to settle down our threat-protection systems? The moment we give up self-blaming and shaming, refuse to see depression as a personal weakness or even be frightened of it (but instead see it as a brain state pattern that has been created in us), we can turn around and face it and do what we can to overcome it. Seeing that the basis of our depression is not our fault is not to say that we aren’t doing things that are making the situation worse, or that we couldn’t help ourselves more than we are. Indeed, we may need to take more responsibility for changing our behaviors, our thoughts or even styles of relating, and work our way out of depression.

The need for kindness

We are going to be looking at many ways that we can tackle depression throughout this book, but there is a key message that I want to convey: whether you work with your thoughts or feelings or your behaviors, if you learn to do it in the spirit of support, encouragement and kindness, this will give you an extra boost to your efforts. Indeed, kindness to yourself may be one of the things that you haven’t been too good at, and one of the skills that require practice. Some of you will be frightened of that idea; you may see self-kindness as an indulgence or weakness or letting yourself off the hook, or you don’t deserve it, or you might feel that if you’re kind to yourself and enjoy life something bad will happen tomorrow; you’ve always got to pay for the good times. Or it may touch sadness in you because it reminds you that you’ve been yearning for kindness and connectedness for a long time. If you are feeling or thinking this, you are certainly not alone! Many depressed people have these types of beliefs and fears. So we are going to work a step at a time. But as I have suggested, think about self-kindness in a different way. Take a physiotherapy approach to your brain and think about exercising/training it – a kind of emotional fitness training. Self-kindness is a way to restart that soothing system and bring balance to your mind.

KEY POINTS

Our brain has been built and designed over many millions of years through a process of evolution.

In our brains today are actually two types of mind. One is the emotional mind, which we share with other animals, that can spring into action quickly with (for example) anxiety and anger. The other is the thinking, imagining, fantasizing mind that can increase or dampen our emotions.

To help guide us through life we have three different types of emotion system in our brain:

– a threat-protection system that helps detect, track and respond to things that threaten us

– a drive system that gives rise to desire and feelings of motivation – a soothing system that helps us feel content, at peace, safe and happy. This system is especially important in social relationships when we feel cared for.

Our thinking and imagining can stimulate any of these three emotion systems. When we focus on threats, interpret situations as threat ening or loss-filled or ruminate on threats and losses, we tend to stimulate the threat-protection system. When we focus on achieving and attending to our efforts we are more likely to stimulate the drive system. When we focus on contentment and kindness we tend to stimulate our soothing system.

This knowledge allows us to take more control of which systems we will stimulate through our thinking, imagination and rumination. We can learn to how to adjust our thinking and behavior, and engage in various exercises for our minds, which can bring these emotion systems more into balance and counteract depressed brain states.

How to do this is the subject of Parts II–IV of this book.

3

How evolution may have shaped our minds for depression

In this chapter we’re going to look at the possible functions of depression, or the purpose behind it. By doing this we can understand that depression is not (just) about an illness or some pathology, but evolution has actually made it possible for our brain to create these states, and we can think about why that is the case.

Emotions and their uses

Let’s start by thinking about the functions of our emotions in general. Different emotions evolved because they help us to see and react to the environment in different ways.1 Emotions guide us (and other animals) towards certain important goals, such as developing relationships, or avoiding harm, or overcoming obstacles. Our emotions make things matter to us. If you didn’t have feelings about things, would anything really matter to you? Let’s look at some emotions related to our threat-protection system. As we look at each emotion think carefully about how they are part of self-protection. They are not designed to give us a hard time but actually to help us.

Anger can be triggered when we are frustrated, or something we want is blocked, or we see an injustice, or if someone puts us down. Anger makes us want to approach the problem, do something about it, ‘sort it out’. Anger can also make us want to retaliate against another person who has upset us or someone we love. When anger gets going, our bodies ‘feel’ a certain kind of way, our minds focus on things that annoy us. We have certain types of thoughts that go with anger; think about your own thoughts when you become angry. There will probably be particular things in your life that trigger anger for you; we all have our buttons that can be pushed. Notice how anger pulls your thinking in certain ways – almost like a whirlpool.

Anxiety is focused on threats; it gives us a sense of urgency, prompting us to do something. Anxiety can make us want to run away and keep ourselves safe and out of harm’s way. When anxiety gets going, it pulls our thinking to focus on dangers and threats. Again, like anger, there will probably be certain things in your life that tend to make you anxious.

Disgust makes us want to expel noxious substances or turn away from them. Disgust feels different from anxiety and anger. It was originally designed to keep us away from poisonous substances, and is commonly believed to be linked to bodily things. When disgust blends with anger, we can have contempt.

Shame is usually a blend of other emotions of anger, anxiety, and disgust. It is an emotion that is specifically linked to a sense of ourselves. Typically, shame makes us want to run away, or close down and be submissive, to avoid rejection. We can have a sense of shame if we think others look down on us.

Guilt makes us wary of exploiting or harming others, and prompts us to try to repair the relationship if we do. We will be looking at shame and guilt in later chapters.

What about positive emotions? What functions do they have?2

Excitement is an emotion that is energizing and directs us towards certain things. We generally feel excited about something we want to do or achieve. We can also have a buzz of pleasure when we do achieve. Positive emotions direct us to things that are helpful to us. We can also get small feelings of pleasure from simple things such as enjoying a meal, or the sun of a warm day, or going for a walk, or talking to a friend.

Contentment is a very different positive emotion to that of excitement. It gives us a sense of being at peace and of well-being. Contentment helps us to stop driving ourselves and ‘wanting’ all the time. This allows us to rest. Interestingly, it’s not an emotion that Western societies focus on very much, but it is key to well-being.

Love and affection are emotions that indicate positive relationships between people and tell our brain that we are safe and tone down the threat system. The feelings help us build bonds, and think about each other when we are not currently in sight. As we noted in the last chapter, affection can have very soothing qualities.

Think of each emotion in this list and ask yourself: ‘What does my body want to do if this emotion is aroused in me? How does emotion direct my thinking? How does my thinking differ if I’m angry or anxious or in love?’ The $64,000 question here is: are you thinking about your emotions, or are your emotions thinking for you? The honest answer can be both, but note that we often get caught up in an emotion and the emotion directs our thinking. Sometimes we haven’t learned how to stand back and not get caught up in the whirlpool and dragged into the emotion. The emotion says ‘think this’, ‘dwell on this’, ‘fret about that’ – and we simply do. But of course it is a two-way street. How we think about things, the interpretations and meanings we put on things that happen to us, can also stir our emotions.

Emotions, then, have certain functions, even if they are unpleasant and painful to us. We sometimes call threat self-protective emotions (of anxiety or anger) negative or bad. However, this puts us in the wrong frame of mind for dealing with them. They are not negative emotions simply because they feel bad: they are part of our self-protection system and once we start to befriend them we will find they are easier to deal with. Or put it this way – there are many good reasons for feeling bad. Imagine what a person would be like who did not have the capacity to feel anger, fear, disgust or guilt. These emotions are part of our being; they have evolved as part of our human nature. We can suffer various painful states of mind because we have normal, innate potentials to switch into them.

We live in a world that stresses the importance of happiness and feeling good. The problem is, you can be led astray by some of these claims because they don’t also tell you that feeling bad is at times a normal, indeed important, part of life – and can be good for you in the long term. Anxiety about failing your exam may make you study hard, or anxiety about certain areas of the town you live in will keep you away from there.

Consider too that if someone we love dies, we can find ourselves in a deep state of grief. And very unpleasant it is too, with its associated sleep problems, crying, pining, anger and feelings of emptiness. We may have learned to share these feelings or to keep a stiff upper lip, but there is, in most of us, a potential grief state of mind. As another example, we all have the potential for aggressive, vengeful fantasies and attitudes: if someone harmed your child, your inner desire for revenge could be intense. Also, of course, we all have the potential for feeling anxious. All these possible feeling states are in our genetic blueprint. There are genetic and developmental differences among us that affect how easily or intensely these emotions can be triggered in each one of us.

Our potentials need to be triggered

We can have innate potentials for many negative (and positive) emotions but never (fully) activate them. Suppose nobody you love dies before you do? In that case you might never have an occasion for profound grief, and even though you almost certainly have the innate capacity to experience grief, you may never actually feel it. If no one does you or your family serious wrong, you may never experience the urgent and repetitive nature of vengeful thoughts and feelings. The fact that many people don’t suffer certain states of mind (e.g., grief, sadistic vengefulness, depression) does not mean they do not have some capacity for them.

We can look at the helpfulness of emotions in terms of four aspects: what triggers the emotion, how intense the emotion is, how long it lasts and how frequently we experience it. There are many factors that can influence each of these four domains, so we can train our mind to work on each aspect of a difficult emotion.

One of the most important aspects of our compassionate, evolutionary approach is therefore to recognize when emotions are helpful, and when they have taken a life of their own, or when our thoughts or style of interpreting things keep us living in the shadows. Emotional systems themselves can rather overpower and ‘take control’ of our thoughts and sense of self. I’m sure we have all had the experience of being anxious or angry, and knowing in our hearts that we are probably letting our emotions run away with us, but without practice it’s sometimes difficult to rein them back.

So what’s the point of depression?

However, you may well ask, what is the point of depression?3 The adaptive value of anger, anxiety and love is easy to see, but depression seems so unhelpful. Well, to be frank, it often is. Now one way to think about this is in terms of balance. For example, a certain level of anger can be helpful but intense anger and aggression often aren’t. Anxiety can be helpful, but intense panics usually aren’t. Although we have a basic anxiety and anger system, for a whole number of reasons these emotions can get out of balance and become too intense, too easily triggered, and last too long.

The first thing to recognize is that depression is partly linked to old brain systems. This is why animals can go into depression-like states, and scientists study those states in animals to understand depression better. We know depression is about toning down positive emotions and toning up threat-focused ones. Our key question is: under what conditions might it have been useful for animals to lose confidence, be less positive, become more threat sensitive, and become less active in their environments? When might it have been useful to have a ‘go to the back of the cave and stay there until it’s safe’ brain state?

When we pose the question in this way we search for answers quite differently than if we assume depression is simply ‘a disease’. You may already have some answers forming in your mind about when it is useful to tone down positive emotions and tone up negative ones. In fact it turns out that there are a number of conditions that can trigger these brain state patterns in animals.3 One is loss of close attachments, particularly in the young, another is social isolation, another is conflict, bullying and defeat, another is helplessness over major stressors, and another is entrapment. When you think about it, there are many situations where we can see a toning down of positive emotions and a toning up of negative ones. In all these situations, the brain will automatically shift into patterns of toning down positive emotions and toning up negative ones.

We can get further insight into this by looking at what the new brain’s abilities for thinking and self-awareness makes of our depression. How do depressed people see our world – what do our minds focus on when we are depressed? Is it love or the loss/lack of love? Is it winning or losing and feeling defeated? Is it harmony or conflict? Is it freedom or entrapment? Is it control or feeling out of control? Well, of course, it is usually the latter in each case. We know that depressed people often lose energy and give up on things; they see themselves as inferior, even worthless; they lose confidence and behave submissively rather than assertively. Just as we can ask, ‘When was it useful to get anxious or angry?’ we can ask, ‘When might it have been useful for our ancestors to give up on things, to see themselves as inferior and to behave submissively?’ There are a few answers.

Stopping us from chasing rainbows

Many people believe it is important for us to follow our dreams; to have clear goals and go after them. There is a lot of wisdom in this. Indeed, being able to decide on goals, the kinds of things you want in life, and committing yourself to try and achieve them is helpful. However, we all know that on this path we will have to cope with disappointments and setbacks, losses and failures. Sometimes we might even need to recognize that the thing we so dearly want is actually out of our reach and we have to change direction. We come to realize that our expectations are too high, we have been chasing rainbows and running to the horizon. This can be hard to acknowledge, and sometimes it’s very difficult to let go.

One view of the value of mild depression, for us and other animals (and keep in mind throughout this section that by depression, we are talking about ‘toned down positive emotions and toned up threat-focused emotions’), is that it helps us to give up aspirations that we are unlikely to fulfil or achieve.4 Supposing you want a bigger house or a better car. You work hard for the money, but you just can’t get enough. At some point your energy and enthusiasm begin to wane and eventually you give up and switch to another possibility; you have to tone down your aspiration. Without any internal signal that could prompt us to give up pursuing the unobtainable, we could well continue to pursue it and so waste a lot of time and energy and end up with nothing. Low mood is a ‘give it up’ signal from old brain systems. Feelings of frustration and low mood can be automatic. At times we have to learn when to override them and keep going or listen to them and make changes in our lives.

Whether the mood is a mild dip or a more serious depression may depend on whether we are able to accept giving up and come to terms with our loss, or whether we keep pursuing the unobtainable and failing. It may also depend on how our new brain, with its thinking, ruminative and self-aware abilities, deals with this loss. If we see having to give up as due to a personal failure, or rejection in some way, this will tone positive emotion systems down even further. You have probably seen this yourself. People who are able to come to terms quickly with having to give up on things and losses, and are able to move on, are less vulnerable to depression than those who struggle to let go, who ruminate, remain frustrated or angry, self-blame, and so forth.

Consider David, who is trying to date Helen. He has strong feelings and desires for her. Over a few months, he builds fantasies and dreams about how great it will be if they can get the relationship working and he tries various things to woo her. Then she agrees to a first date, but at the end of the first date, Helen says, ‘Thank you, I’ve had a lovely time but I don’t want to make it a long-term relationship; so it’s a one-off for me.’

It is normal and natural for David to have a dip in mood in response to this disappointment and setback, because it’s the end of his striving, plans, fantasies (that gave good feelings) and hopes. He must now live in a world where those fantasies and desires are not going to happen. Not only has he lost the possibility of the future he wanted with Helen, but also it is the end of the fantasies that gave him good feelings and stimulated his excitement system. Consider what David would need to do to get depressed about this. What would he think about and dwell on? And now, in contrast, consider what he could do to get over this sad but not uncommon event as soon as possible and move on.

Interestingly, we know that some depressed people don’t know how to tolerate and accept painful feelings, how to think and behave, to move on from major life setbacks. They can get stuck, in various ways. They tell themselves that feeling the pain of setbacks and disappointments is awful and unbearable, and are desperate to escape from those feelings, rather than learn how to ‘be with them and work through them’. Or they may be angry and demand that life shouldn’t be like this – when clearly life is often unfair and harsh. Sometimes people go in for self-blame or ruminating, hoping this will help them find a way to control things in the future. For some a loss might bring back painful memories of previous rejections, perhaps from childhood, and feeling unlovable. David might even make this sad situation worse. He might start to phone Helen up, trying to change her mind; or he might become unhappy and try to woo her by making her feel guilty. He might tell her he is drinking, or even that he is now depressed. There are many ways he could behave that will actually turn Helen’s positive feelings for him quite negative. She would then reject him more harshly, which will then hurt him more, which would then feed into his feelings that he is unlovable, or other people are uncaring. David probably won’t recognize that his own behavior is part of the problem here.

The point is that we can’t avoid the pain of life, and dips in mood are normal reactions to major setbacks. Learning tolerance and acceptance of life’s pain is at times the way forward. What we can do is learn how to treat ourselves kindly and compassionately to get through these difficult waters. We can also learn how to let go gently, and this means coming to terms with grief as part of life.

Reactions to loss: depression and grief

Coming to terms with not being able to be as we wish, or have what we want, or the relationships we want, is about grieving and our ability to allow ourselves to grieve. It has been suggested that some forms of depression are like grief. Grief can have a social and a non-social aspect. For example, think of the footballer with a promising international career who damages his knee and can no longer play. Sickness, illness (including mental illness) and injury are common reasons for changing the course of one’s life and can require a lot of adjustment and grief work. We are confronted with grief for the loss of the person we wanted to be or hoped to become. As for David above, these losses also involve the loss of a fantasy life, the loss of how we would enjoy imagining, planning and thinking about how we were going to be, how life was going to be, what we would be part of.

Loss of feelings of connectedness

Responding to the loss of a loved one with pining, anger, anxiety, sadness, loss of positive feelings and motivation is the way our threat-protection systems respond to important losses. Many young animals, including rat pups, baby monkeys and human infants, can show what we call a ‘protest–despair’ response to separation from, or loss of, the mother or those they have affectionate bonds with. Commonly, at first the infant protests and becomes more active (restless, angry and anxious, and in humans tearful) but if the mother does not return the infant becomes quiet and withdrawn. This condition has been called a despair state. What on earth could be the value of such a display or state? Keep in mind that this is toning down of positive emotions and toning up threat-protection. For juveniles in the wild, who are unprotected by a parent, it is important that they don’t move around too much, get lost, get dehydrated in the sun, or that their crying and obvious distress attract the attention of predators. The way evolution designed this was to create a potential brain pattern that would tone down positive emotion and tone up negative emotion. The infant will go into a very anxious and vigilant state, which urges it to hide away.

We think that something like this brain state and pattern can be triggered in depression, because the depressed person often feels as if they are disconnected from others, alone and lonely, cut off, and, without a sense of connectedness, the world feels dangerous to them. The ‘go to the back of the cave strategy’ switches in and they lose energy, confidence and motivation to go into the world.

The mechanisms for coping with loss, which have evolved over millions of years, seem to be the rough blueprint for many of our human responses to serious personal losses. We too can go through a protest stage of feeling angry and looking for the loved one, followed by numbness and despair. Of course, most grief in humans is complex, and people can move back and forth through several phases, so I do not mean to oversimplify it, only to indicate that there are evolved mechanisms at work. ‘Attachment losses’ are painful and stressful because we are biologically set up for them to be so. Having these feelings arise in us is not our fault – but we need to think how we can help and heal them.

In some depressions the protest–despair mechanism works in very subtle ways. It is as if there is a continuous background sense of not really feeling close enough or connected enough to others, and yet desperately wanting to. Sometimes depressed people will say they have a background feeling of always ‘feeling alone and disconnected from others’. Sometimes people become depressed even though they have not recently experienced any actual major loss, but in the course of therapy it may turn out that they have never felt loved or wanted by their parents or partners, and are in a kind of grieving–yearning state for the closeness they lack.

Loss of our ideal other

There are always two types of parent in our heads: the one that we had, and the one that we wanted. If these are too far apart, people can experience conflicts over the one they actually had (warts and all) – and desires for the one they wanted (protecting, affectionate and understanding). If we had difficult relationships with parents, it is easy to forget that sometimes we may need to grieve for the parent we so wanted and never had, and work out how to deal with those feelings. One depressed woman, when considering this, acknowledged that she had never really allowed herself to think about the kind of mother she had wanted, because she had felt disloyal to her own (angry and depressed) mother. However, giving herself permission to think about this allowed her to grieve for the mother she had wanted. This helped her to ‘feel more at peace within myself and give up trying to pretend or hope that my mother could be anything other than she is. She can never be as I want her to be.’