Terminology and ‘Structure’:

the Dieri Case

I

Les Structures élémentaires de la parenté is generally considered not only as one of the pivots in modern anthropological theory but also as a masterpiece of empirical analysis. We intend to assess its actual virtues in this respect by considering here one of the analyses Lévi-Strauss undertakes. We have chosen the Dieri case in particular because of its importance in earlier anthropological works, and because of the ‘anomalous’ character that Lévi-Strauss ascribes to it.1

As in the case of Wikmunkan society (Lévi-Strauss 1949: 246-51), Lévi-Strauss considers the Dieri system as an example of transition from ‘generalized’ (asymmetric) exchange to ‘restricted’ (symmetric) exchange (1949: 260-2).2 The Dieri system presents, according to Lévi-Strauss, a great many analytical difficulties, mainly due to the fact that it exhibits the ‘structure’ of a moiety system and the rule of marriage corresponding to a so-called Aranda system (eight sections), namely marriage with the mother’s mother’s brother’s daughter’s daughter, or, in general, marriage between children of first cross-cousins, with prohibition of marriage between first cross-cousins (Lévi-Strauss 1949: 256). On the other hand, and in spite of Radcliffe-Brown’s efforts, the Dieri system cannot be treated as an Aranda system, says Lévi-Strauss, because it is only ‘apparently systematic’ and ‘contingent lines are needed in order to close a malformed cycle’ (Lévi-Strauss 1949: 204).

Lévi-Strauss analyses the Dieri system in chapter XIII of Les Structures élémentaires de la parenté, under the heading ‘Harmonic and Dysharmonic Regimes’, the main argument of which, as we have already seen in chapter 2, relies on the relationship between those regimes and the different types of ‘elementary structures’. The relationship posited is that systems of ‘generalized exchange’ can take place only in ‘harmonic regimes’ (matrilocal and matrilineal or patrilocal and patrilineal), while systems of ‘restricted exchange’ correspond to ‘disharmonic regimes’ (patrilocal and matrilineal, or matrilocal and patrilineal).

The aim of this chapter is to reconsider the Dieri case in order to assess the validity of Lévi-Strauss’s interpretation and hypothetical reconstruction of the evolution of the system. The analysis involves the consideration of the logic of a system recognizing four terminological lines and makes it possible, on the other hand, to follow Lévi-Strauss’s actual use of his analytical criteria, namely: type of exchange, linearity and locality, and, fundamentally, the role of the so-called kinship terms in the assessment of a ‘structure’.

II

The first ethnographic report on the Dieri was published in 1874 by S. Gason, a police trooper working in the Dieri area. Gason was also, together with the missionaries O. Siebert, J. G. Reuther, and H. Vogelsang, one of Howitt’s informants. Howitt did his fieldwork among the Dieri around 1870 and after publishing some articles relating to them (Howitt 1878; 1883; 1884b; 1890; 1891) he produced the most complete ethnographical account of the Dieri in his book The Native Tribes of South-East Australia (1904). Although there was no further ethnography until Elkin’s fieldwork in 1931, the anthropological literature on the Dieri in the first decade of the century is considerable.3 After the publication of

Howitt’s works, the theme of ‘group marriage’ among the Dieri, and the concomitant anthropological theory, aroused the interest of anthropologists such as Lang, Thomas, and Frazer. While Frazer’s treatment of the Dieri (1910) is almost a mere repetition of the ethnographical facts provided by Howitt, the works of Lang and Thomas (Lang 1903, 1905; Thomas 1906b) still constitute remarkable pieces of anthropological theory, and their discussions with Howitt (Lang 1907, 1909; Thomas 1906a) did throw light on some obscure points in Dieri ethnography.

Before Elkin’s fieldwork, Radcliffe-Brown devoted an article to the analysis of the Dieri relationship terminology (Radcliffe-Brown 1914), and after Elkin’s fieldwork and new interpretation of the system (Elkin 1931, 1934, 1938a), Lévi-Strauss included a new analysis of it in Les Structures élémentaires de la parenté (1949).

In 1946 the Dieri were reported as numbering fewer than 60 and as being in a state of complete dissolution (Mant 1946: 25). By the time Howitt wrote his Native Tribes of South-East Australia (1904), the native tribes of this area were already in a process of rapid disintegration. For this reason Howitt decided to rely only on the ethnographic material gathered before 1889 (Howitt 1904: xiii). Howitt described the Dieri as ‘the largest and most important [tribe] occupying country in the Delta of the Barcoo River on the east side of Lake Eyre’ (Howitt 1891: 31). According to Gason, they numbered about 230, while the total number of all the groups of Cooper’s Creek was estimated by Gason and Howitt at about 1000 to 1200. Among them, the Dieri were reported as ‘superior’ and according to Howitt they spoke of themselves as the ‘fathers’ of their neighbouring groups (Howitt 1891: 31).

When referring to the Dieri, Howitt in fact describes the characteristics and social organization of several local groups

which either recognize a relationship to each other in stock, which is exhibited in their language and in custom, or where the relationship is not acknowledged or has not been ascertained by my informants, it may yet be inferred from the community of custom (Howitt 1891: 31).

Following the information gathered by T. Vogelsang, Berndt describes them as inhabiting the eastern shores and the neighbouring country of Lake Eyre and consisting of two main groups, the Cooper’s Creek Dieri or Ku’na:ri and the Lake Hope Dieri or Pandu. These two divisions were bordered by the Ngameni, Jauraworka, and Jantruwanta tribes (Berndt 1939: 167). Dieri territory is reported as deficient in foodstuffs. Dieri hunting activities consisted in the gathering of various species of rats, snakes, and lizards, and owing to the scarcity of these animals their food was principally vegetable (Gason 1879: 259).

It is not possible to gain a clear picture of the physical distribution and exact composition of the local groups. Howitt describes them as follows:

As an entity it [the Dieri community] is divided into a number of lesser groups, each of which has a name and occupies a definite part of the tribal country. These are again divided and subdivided until we reach the smallest group, consisting of a few families, or even only a single family, which claims also a definite part of the tribal country as its inherited food ground. These groups have local perpetuation through the sons, who inherit the hunting grounds of their fathers (Howitt 1891: 34).

Thus, although it is clear that they were patrilocal, there is not a hint in the above quotation, any more than there is in the rest of the literature, of how these local groups were composed. Taking into account that the inheritance of the totems related to exogamy was matrilineal, to imagine these local groups becomes specially difficult; but with these data it is clearly not possible to think that, as Radcliffe-Brown asserts of Australian societies in general, ‘it seems that normally all the persons born in one horde belong to a single line of descent’ (Radcliffe-Brown 1931: 105).

They were divided into exogamous moieties, which they called murdu. The word in Dieri means ‘taste’ (Gason 1879: 260) and, according to Gason’s vocabulary, in its primary and larger signification it implies ‘family’ (Gason 1879: 260; cf. Gatti 1930: 107). The accounts of their legends about the creation of their moiety system are somewhat dissimilar. According to Gason, the Dieri believed that their division into exogamous totemic groups belonging to each moiety was created by the Mura-Mura (good spirit) in order to prevent the evil effects of intermarriage within a single promiscuous group (Howitt 1904: 480-1). Another informant, O. Siebert, tells the legend as referring to the imposition of exogamy upon already existing moieties, which was decided by the pinnauru (elders) because of the same reasons (Howitt 1904: 481; Howitt and Siebert 1904: 129). The discrepancy about whether the Dieri believed in the simultaneous creation of moieties and a system of symmetric alliance, or in the preexistence of the former over the latter, could just mean that the Dieri actually held both legends; but Siebert’s account demonstrates once more that the relationship between sections and a symmetric rule of marriage is not necessary and sufficient.4 The moieties were named Matteri and Kararu, and, according to Helms, these terms were used ‘to distinguish the leading strains of blood’ (Helms 1896: 278).

The twenty-six totems designating exogamous groups were inherited from the mother and were divided between the moieties, Kararu and Matteri (Howitt 1904: 91), as follows:

| Kararu | Matteri |

| Talara (rain) | Muluru (a caterpillar) |

| Woma (carpet-snake) | Malura (cormorant) |

| Kaualka (crow) | Warogati (emu) |

| Puralko (native companion) | Karawora (eagle-hawk) |

| Karku (red ochre) | Markara (a fish) |

| Tidnama (a small frog) | Kuntyiri (Acacia sp.) |

| Kananguru (seed of Claytonia sp.) | Kintala (dingo) |

| Maiaru (a rat) | Yikaura (native cat) |

| Tapaiuru (a bat) | Kirhapara |

| Dokubirabira (the pan-beetle) | Kokula (small marsupial) |

| Milketyelparu | Kanunga (kangaroo-rat) |

| Kaladiri (a frog) | |

| Piramoku (the rabbit-bandicoot) | |

| Punta (shrew mouse) | |

| Karabana (a small mouse) |

Howitt also provides in his book the corresponding totems of the neighbouring tribes with which the Dieri intermarried. According to the reports there was no correspondence between the totems of the opposite moieties, so the Dieri could marry a person belonging to any totem group, provided that this totem group was from the opposite moiety, and provided that the person was not a kami to Ego.

From the matrilineal inheritance of the totems Howitt concludes that they were ‘matriarchal’ (Howitt 1891: 36). But this question of descent, defined according to the inheritance of these exogamous totems, gave rise to the first academic discussion related to the Dieri. In spite of Howitt’s remarks on the inheritance of totems, Gason, in a letter sent to Frazer, writes:

The sons take the father’s class, the daughters the mother’s class, e.g. if a ‘dog’ (being a man) marries a ‘rat’ (being a woman) the sons of the issue would be ‘dogs’, the daughters of the issue would be ‘rats’ (Gason 1888: 186).

Howitt, who declares that he ‘cannot believe [his] eyes’ at the sight of Gason’s statement, replies that:

The Dieri said all the children, both girls and boys, take the murdu of their mother and not of the father (Howitt 1890: 90).

The point in dispute was decisive for one of the main theoretical issues at the time, namely, Morgan’s hypothesis on the evolution of societies from a matriarchal to a patriarchal stage. Lang, therefore, saw in Gason’s alleged mistake a sign of the change in the rule of descent of the Dieri. Gason’s confusion arose from the fact that on certain occasions:

A man gives his totem name to his son, who then has those of both mother and father. This has been done even in the Dieri tribe. Such a practice leads directly to a change in the line of descent (Lang 1909: 284).

Whether the Dieri were changing their ‘line of descent’ is, according to the evidence, not possible to know, but although Howitt was eagerly trying to test Morgan’s ideas, he remained on this point faithful to his ethnographic data. The sons belonged to the same totemic cult groups as their fathers, but these cult totems, unlike the social totems which were inherited from the mothers, had no bearing on marriage and exogamy (Elkin 1938: 50).

Thus an individual belonged to the moiety to which his mother and mother’s brother did, and which was transmitted by the inheritance of the mother’s totem; and since marriage was patrilocal, he belonged to the local group of his father. Such an organization is also revealed by the fact that:

the members of the class divisions [i.e. moieties] of the Dieri are distributed over the whole tribal country in the various local groups. The divisions are perpetuated by the children inheriting the class name and the totem name of their mother (Howitt 1891: 36).

Each totemic group had as its head a pinnauru, the eldest man of the group belonging to that group, and each local group (horde) had also a pinnauru, who could also be the head of the totem. The elders were collectively the heads of the tribe and they decided any communal matters, including marriage arrangements (Howitt 1904: 297-9).

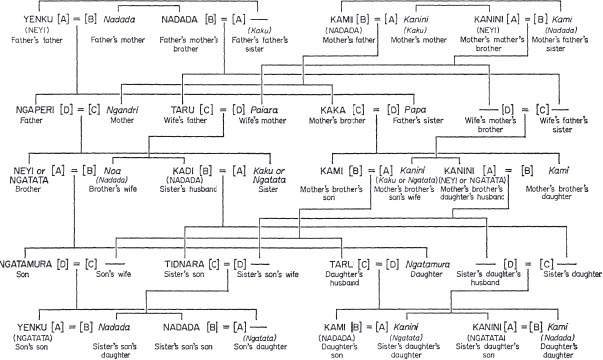

According to Howitt (1904: 160), the Dieri terms of relationship were as in Table 4. The term kaia-kaia was applied to the mother’s mother’s mother, who was ‘more commonly called ngandri, since she is the mother of the kanini’ (Howitt 1904: 164).

The account of the relationship terminology is incomplete, as Elkin’s report demonstrates (Elkin 1931), and contains some obscurities concerning the specifications of the terms nadada and kami (both rendered as MF); but it permits, nevertheless, the determination of one of the basic features of the Dieri form of classification. The fact that we are dealing with a lineal terminology is indicated by the equations:

| FF = FFB (yenku) | F = FB (ngaperi) | |

| MM = MMZ (kanini) | M = MZ (ngandri) |

As Howitt presents it, it is not possible to tell if it is a prescriptive terminology, or, if it is, whether it is symmetric or asymmetric; but the characteristics he gives concerning Dieri institutions suggest the possibility of a symmetric prescriptive terminology. These characteristics are:

1 an explicit prescription of marriage regarding one specific terminological category;

2 exchange of sisters; and

3 reallocation of categories.

Characteristic (1) refers to the rule of marriage concerning the category nadada. Howitt refers to a Dieri saying that ‘those who are noa [potential spouse] are nadada to each other’ (1904: 163). There was prohibition of marriage between people who were kami (genealogically specified as MBC, FZC) to each other, and those who were nadada to each other were the children of people who were kami to each other. Even if in Howitt’s account of the Dieri relationship terminology the term nadada applies to individuals (MF, DC), in the second ascending and second descending genealogical levels, the term also applied to individuals of Ego’s genealogical level (the children of first cross-cousins). Thus the rule to marry a nadada applied to people situated in the same genealogical level and also in alternate levels. This identification of individuals belonging to alternate genealogical levels explains the Dieri practice of marrying the daughter’s daughter of an elder brother (Howitt 1904: 164) and enabled Rivers to compare the Dieri system with that of Pentecost (Rivers 1914: 58).

| 1. | yenku | FF, FFB, SS |

| 2. | nadada | MF, DC |

| 3. | kami | MF, DC, MBC, FZC |

| 4. | kanini | MM, MMZ, CC, grand-nephew or niece, DC (w.s.) |

| 5. | ngaperi | F, FB |

| 6. | ngandri | M, MZ, MMM |

| 7. | papa | FZ |

| 8. | kaka | MB |

| 9. | paiara | WM |

| 10. | neyi | eB |

| 11. | kaku | eZ |

| 12. | ngatata | yB, yZ |

| 13. | noa | 'potential husband or wife’ |

| 14. | kadi | WB |

| 15. | yimari | WZ |

| 16. | kamari | HZ |

| 17. | buyulu | MZC |

| 18. | ngata-mura | S, D (m.s.) |

| 19. | ngatani | S, D (w.s.) |

| 20. | tidnara | ZS |

| 21. | taru | DH |

| 22. | kalari | SW, HM (w.s.) |

Characteristic (2), exchange of sisters, was, according to Howitt (1904: 161) a concomitant of the tippa-malku (i.e. individual) type of marriage. Howitt distinguished this type of marriage from what he called pirrauru marriage and considered a form of ‘group marriage’. The tippa-malku type of marriage was for Howitt the ‘individual’ marriage among the Dieri and was the result of the betrothal of a boy and a girl who were in the relation of noa to each other. The betrothal was arranged by the mothers of the children, who were kami to each other, and their brothers, and in every such case there had to be ‘exchange of a sister, own or tribal, of the boy, who is thereby promised as a wife to the brother, own or tribal, of the girl’ (Howitt 1904: 177).

Characteristic (3) refers to the Dieri practice of changing the relationship between two women from kamari (HZ) to kami, in order to convert their children from kami to noa and thereby to allocate them to the marriageable category. Howitt reports that this was the practice among the Dieri whenever there was not a noa available for a Dieri individual (Howitt 1904: 190). He presents several examples. In one of them:

a woman having four sons who were kami-mara [mara can be translated as ‘relationship’] to two unmarried girls, it was arranged with her and her brethren that one of her sons should be placed in the noa-mara relation with one of the girls, while still remaining in the kami relation with the other. . . . Thus the tippa-malku relation became possible.

In another example (p. 167), he presents the following case:

two brothers married two sisters, and one had a son and the other a daughter. These, being the children of two brothers, were brother and sister. Each of them married, and one had a son and the other a daughter, who were kami-mara. Under the Dieri rules these two could not lawfully marry; but since there was no girl or woman noa to the young man and available, he could not get a wife. The respective kindreds, however, got over the difficulty by altering the relationship of the two mothers from kamari (brother’s wife) to kami, by which change the two young people came into the noa relationship.

In such cases, the mother-in-law was not called paiara but kami-paiara, to denote that it was an alteration in the relationship and because all the other relationships involved were not changed.

What the practice demonstrates is the primacy of classification over consanguineal ties, and it relates to prescription in that the same custom can be found in some asymmetric systems (cf. Kruyt 1922:493).

III

The second discussion relating to Howitt’s interpretation of the Dieri system arose from his account of the pirrauru relationship. To prove Morgan’s ideas it was certainly essential to discover an example of ‘group marriage’, and because

the origin of individual marriage, the change of the line of descent, and the final decay of the old class organization are all parts of the same process of social development (Howitt 1888: 34),

it ought presumptively to be found in a society with matrilineal descent and marriage classes. The Dieri were, it was held, such a case. They exhibited a number of supposed symptoms of ‘primitiveness’, namely: (1) matrilineal descent, (2) a ‘classificatory’ terminology, and (3) named exogamous moieties. Even though these traits were known to be common in other societies, Howitt saw the Dieri as though it were a singular example of a society which was still in transition from ‘group’ to ‘individual marriage’, and saw as an indicator of that transition the fact that the Dieri practised both ‘individual’ and ‘group’ marriage.

According to Howitt, the pirraura relationship arose from the exchange by brothers of their wives, and thus ‘a pirrauru is always a “wife’s sister” or a “brother’s wife”,’ and ‘when two brothers are married to two sisters, they commonly live together in a group-marriage of four’ (Howitt 1904: 181). The category of ‘marriageable’ women from a ‘group marriage’ point of view was the same category as in the tippa-malku (i.e. individual) form of marriage. In both instances the women had to belong to the opposite moiety and had to be not a kami but a noa (that is, the daughter of his mother’s kami and therefore a nadada to him). In fact, as Howitt refers to it, a man could have a woman as his parrauru provided he was a noa to her (Howitt 1904:181). From data collected by the missionary Otto Siebert, Howitt interpreted the kandri ceremony as the act by which the heads of the totems allotted the marriageable people of each totem into groups of pirrauru (Howitt 1904: 182).

Thus, for Howitt, this example of group marriage was proof of the hypothesis which stated that classificatory terminologies were the remnant of a state prior to individual marriage. If ‘group marriage’ actually existed, that was a good explanation for classificatory terms. A child applied the term equivalent to our ‘mother’ to a group or women, because his or her father had several wives. The same explanation applied for the equivalent of ‘father’ and for each classificatory term. But there were other facts to be explained, and the possible explanations did not need to follow Morgan’s ideas of the ‘undivided commune’ and the subsequent ‘group marriage’. ‘Exogamy’ and ‘incest prohibitions’ had also to be understood, as well as ‘totemism’, and for these there was another possible evolutionary line arising from Darwin’s idea that man aboriginally lived in small communities, each with a single wife. Lang, while approving Morgan’s hypothesis concerning the primacy of matrilineal descent over patrilineal descent, followed Darwin’s hypothesis of the historical universality of individual marriage (Lang 1905: vii; 1911: 404) and, together with Thomas, saw the practice of the pirrauru among the Dieri (or the equivalent piranguru among the Arabana) as a later development of individual marriage and, moreover, not classifiable as ‘marriage’ at all (Lang 1905: 35-58). Moreover, as Thomas observed, ‘if there was a period of group marriage there was also one of group motherhood’ (Thomas 1906b: 123).

This approach was able to elucidate the meaning of classificatory terms from a very different point of view. Modern conceptions of relationship terminologies approve Lang’s and Durkheim’s view of the problem rather than the line of interpretation derived from Morgan,5 about which Lang says:

the friends of group and communal marriage keep unconsciously forgetting, . . . that our ideas of sister, brother, father, mother, and so on, have nothing to do . . . with the native terms, which include, indeed, but do not denote these relationships as understood by us (Lang 1903: 100-1; original emphasis).

One demonstration of this proposal was to be found in the Dieri use of their relationship terminology. The fact that the term kami, for instance, denoted for the Dieri more a certain status than consanguineal ties is shown by the practice, mentioned above, of reallocating individuals to different categories. When a man could not find a noa available for betrothal to him, his mother and another woman who was a kamari (HZ; BW) to her were made kami by their brothers, so that their children should become noa to each other. Howitt adds that this practice was a common one among the Deiri.

Going back to the pirrauru relationship, Gason’s first translation of the term was ‘paramour’ (Gason 1879: 303), and this was also Lang’s interpretation: pirrauru were ‘legal paramours’ and their existence denoted for him a more advanced rather than a more primitive trait (Lang 1905: 50-8). What kind of an institution it was is difficult to tell just by looking at the ethnography, because even the kandri ceremony, which was described by Howitt in 1904 as the allotment of the pirrauru groups, was described by him in 1907 as:

the kandri ceremony announces the ‘betrothal’, as I call it, of a male and a female noa, no more and no less (Howitt 1907:179).

Thus the ceremony was related by Howitt to both ‘group’ and ‘individual’ (tippa-malku) marriages. The evidence Howitt gives actually fits better with Lang’s interpretation, and what Howitt called ‘group marriage’ was probably the fact that groups of brothers with their individual wives lived in the same local group. Within those groups every classificatory brother was a noa to each one of his brother’s wives. It is probable then that the term pirrauru denoted those individuals who were marriageable to each other and lived together in a local group, because what seems to be true, as Thomas says, is that even if all the pirrauru had to be noa to each other, not all the noa people were pirrauru to each other. So for any individual the noa groups was wider than the pirrauru group (Thomas 1907: 308).

It could also be plausible, then, that both interpretations given by Howitt to the kandri ceremony were valid, and that therefore the ceremony served two purposes for the Dieri, namely: (i) to establish ‘individual’ (tippa-malku) marriages, and (ii) to indicate which groups of noa were going to live in the same local group after marriage. But what seems to be indisputable is Thomas’s demonstration that the pirrauru relationship – even if it was, as Howitt saw it, a kind of ‘group marriage’ – still did not explain the use of classificatory terms, because Howitt in one passage talks about the ‘application of the term ngaperi (father) to the other brothers who have not become pirrauru’. As Thomas specifies, they applied the term ngaperi ‘to all the men of the noa group’ (Thomas 1907: 309). Hence, for the use of the classificatory term ngaperi, the only fact that the Dieri needed to take into account was who were the ‘marriageable’ (noa) men for their mothers, regardless of the consideration whether they were pirrauru to their mothers or not.

In taking the pirrauru relationship as the example of ‘group marriage’ Howitt did not follow Fison’s definition of the term. For Fison, in the expression ‘group marriage’:

the word ‘marriage’ itself has to be taken in a certain modified sense. . . . It does not necessarily imply actual giving in marriage or cohabitation; what it implies is a marital right, or rather a marital qualification, which comes with birth (Fison 1893: 689).

According to this definition, Howitt did not need to use the pirrauru relationship in order to present an example of ‘group marriage’. He could just look at the characteristic of the Dieri system described by himself as:

a boy at his birth acquires a marital right as regard those women of the other class-name who are not forbidden to him under the restrictions arising from consanguinity (Howitt 1883: 457; cf. 1904:165).

Fison was therefore looking for a quite different kind of institution than the pirrauru marriage as described for Howitt. As Needham says:

in the last quarter of the nineteenth century the study of what was taken to be ‘group marriage’ in Australia brought into prominence an institution which Durkheim named ‘connubium’ and has more recently been termed prescriptive alliance (Needham 1964c: 125-6).

Considering ‘group marriage’ in this way, it is quite clear that: (1) among the Dieri the alliance system was certainly a prescriptive one, and (2) Lang’s and Fison’s apparently so different conceptions of ‘classificatory’ terms need not be explained as deriving from consanguineal ties, and (3) within the different modes of social classification, prescriptive terminologies constitute a definite type which corresponds symbolically to the idea of ‘connubium’ between categorically defined groups or persons.

IV

In 1914 Radcliffe-Brown devoted an article to the consideration of obscurities and possible errors in Howitt’s account of the Dieri relationship terminology (Radcliffe-Brown 1914). He first pointed out certain defects in Howitt’s analysis of the genealogy presented facing p. 159 of The Native Tribes of South-East Australia (1904). Howitt’s statement that an individual stands in the position of kaka, MB, to another because he is ngaperi, F, to him, is obviously wrong (Howitt 1904: 166). Radcliffe-Brown gives two more instances (p. 53) in which Howitt makes the same sort of mistake, and finally examines Howitt’s specification of the terms nadada and kami, both rendered as mother’s father (Howitt 1904: 160-2). Radcliffe-Brown thought the identification of the two terms was a possible error and suggested a correction: the term nadada should be specified as father’s mother and father’s mother’s brother, but also ‘in a looser and more extended sense’ as mother’s father (1914: 54). He claimed that in this way it was easier to understand the Dieri saying that ‘those who are noa are nadada to each other’, because:

I am the younger brother (ngatata) to my father’s father’s sister, and she is nadada (father’s mother) to the woman I call noa. It follows that as I am brother to the nadada of my noa I am nadada to the latter and she is nadada to me (Radcliffe-Brown 1914: 54).

If this suggestion were accepted, the Dieri system would be, said Radcliffe-Brown, ‘wonderfully simple and logical and quite in agreement with other systems in Australia’ (1914: 54), so he drew a table (Figure 6) showing a system of relationship which, according to him, proved ‘the existence of the four matrimonial classes in the Dieri tribe’ (1914: 56). By ‘matrimonial classes’ he meant, as he explained, ‘divisions of a tribe such as those named Ippai, Kubbi, Kumbo and Murri in the Kamilaroi tribe’ (p. 56, n.; cf. Fison and Howitt 1880: 42; Howitt 1904: 201). He pointed out in a footnote that many writers (such as Howitt, Frazer, Thomas, Schmidt), assumed the non-existence of four matrimonial classes because in some tribes those classes were not named (as in the case of the Dieri). ‘There is not a scrap of evidence at present for the existence in Australia of any tribe which has not four divisions of this kind.’ The four classes, he claimed, ‘certainly do exist’ among the Dieri.

But if they were not named, and their existence was simply deduced by Radcliffe-Brown from the composition of the relationship terminology, why should anybody call these inferential constructs ‘classes’? Moreover, if ‘class’ was the term he employed to denote a certain possible arrangement of relationship terms in a diagram representing a system, why employ the term ‘class’ at all and not refer to that arrangement to classify the system? If systems had to be classified into different ‘class’ types, whether the classes ‘were named or not’, then the classification denoted a categorization of systems of ‘classes’ the indicators of which were to be found in possible arrangements of the relationship terms, no matter whether or not the classes actually existed. One wonders why one should not classify the systems directly by the composition of their relationship terminologies, and then just provide the ethnographical information on whether or not a particular society with a particular terminological system possessed a corresponding set of marriage classes.

Anyhow, some years later, in The Social Organization of Australian Tribes, Radcliffe-Brown represents the Dieri as having instead ‘a kinship system of the Aranda type’ (1931: 48). If so, however, why are they not included there under the heading ‘Aranda type’ (p. 74) but are instead classified separately as the ‘Dieri type’? It seems quite arbitrary to consider that a system which does not possess named classes, but has a terminology consistent with a ‘four-class’ system, possesses in fact ‘classes’ that are not named, and then not to follow the same reasoning when a society possesses no sections but has a ‘kinship system’ conforming to an ‘eight-section’ type.

In 1951 Radcliffe-Brown deals again with the Dieri system, but this time the Dieri have for him ‘a highly organized system of double descent’ (1951:40), derived from the existence of patrilineal totemic groups (pintara) and matrilineal totemic clans (madu). According to him, the Dieri are in close association with the matrilineal totem of the father. As they are also, he says, in a close association with the patrilineal totemic clan of the father’s father and with the matrilineal clans of the mother and the father’s mother, each Dieri individual seems to be connected with all possible totemic groups in the Dieri community. On the basis of the available ethnography, however, the interpretation of the Dieri system as a system of ‘double descent’ is very difficult to prove. The pintara totem that sons inherited from the father was of a very different nature from the cult totem inherited from the mother. Only the matrilineal totem was related to exogamy, because ‘flesh and blood’ were inherited from the mother. The pintara they received from the father was related instead to locality and war (cf. Elkin 1938: 50).

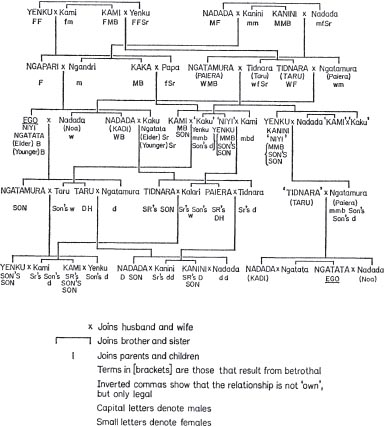

V

As a matter of fact, there was a mistake in Howitt’s account of the Dieri relationship terminology, but not in the respect that Radcliffe-Brown sought to correct. From his own fieldwork, Elkin provided a full account of the terminology which is consistent with Howitt’s report, except for the specification of the term kami (Elkin 1931: 494; 1938a: 49). The correct specification for kami was father’s mother, and that for nadada was mother’s father (see Table 5), and as Elkin remarks: ‘In Howitt’s list there would be no term for father’s mother if the “mother’s father” [which Howitt gave as the specification of both kami and nadada] is not regarded as a simple transposition of words’ (1938:49; cf. Figure 7). Elkin describes the system as having certain features in common with the Aranda type, namely: reckoning of descent through four lines, the use of four terms in the second ascending genealogical level, prohibition of marriage between first cross-cousins, and a rule of marriage with second cross-cousins. He notes, however, some differences from an Aranda system, for instance the fact that in an Aranda system cross-cousins are classified with MMBW, while among the Dieri they are classified with FM (kami).

The table by which Elkin represents the Dieri relationship terminology shows one of the characteristics of the system regarding certain categories in the first ascending, the first descending, and Ego’s genealogical level: some positions are denoted by two terms (tidnara-taru, ngatamura-paiera, nadada-noa, nadada-kadi); one of these denotes potential affines and the other actual affines. WM, for instance, is categorically a ngatamura to Ego, that is the daughter of one of Ego’s nadada and the mother of one of

| 1. | yenku | FF, FFZ, MMBSS, MMBSD, SS, SD, ZSDH, ZSSW |

| 2. | nadada | MF, MFZ, MMBW, WMM, WMMB, W, MMBDD, MFZDD, WB, DC |

| 3. | kamt | FM, FMB, WFF, FZS, FZD, MBS, MBD, ZSS, ZSD |

| 4. | kanini | MM, MMB, WMF, WMFZ, MFZH, ZDS, ZDD |

| 5. | ngapari | F, FB |

| 6. | ngandri | M, MZ |

| 7. | papa | FZ, MBW |

| 8. | kaka | MB, FZH |

| 9. | tidnara | FFZC, ZC |

| 10. | taru | WF, SW, DH, DHZ |

| 11. | paiera | WM, WMB, ZDH |

| 12. | ngatamura | MMBC, S, D |

| 13. | niyi | eB, WZH |

| 14. | kaku | eZ, WBW |

| 15. | ngatata | yB, WZH, yZ, WBW |

| 16. | noa | W, H |

| 17. | kadi | WB |

| 18. | kalari | ZSW |

Ego’s nadada, but because she is the mother of Ego’s actual noa (W), she becomes paiera to Ego.

Another characteristic of the system is that each of the terms that denote actual and classificatory brothers and sisters (niyi; kaku) is added to the term yenku, at Ego’s genealogical level, to denote the people of Ego’s genealogical level who belong to Ego’s moiety but not Ego’s line.

Elkin also reports that ‘the Dieri is no exception to the Australian custom of the betrothal and marriage of young girls to men much older than themselves; the difference may be about thirty years’, and he adds that ‘the two persons concerned usually belong to alternate generations, as when there is an exchange of sister’s daughters between two men who are related as man and wife’s mother’s brother’ (1938a: 58). Because the Dieri identify categories belonging to the same line and in alternate genealogical levels, such marriages between old men and young girls are easy to understand. A Dieri man marries a girl who is a nadada to him and the daughter of a woman who is ngatamura to him. But ngatamura is a term that designates positions in the first ascending and the first descending genealogical levels of the nadada line, and the spouses necessarily therefore belong either to the same genealogical level or to alternate levels. Marriage between people who belong to different genealogical levels seems to be qualified in one respect: the husband belongs to the higher genealogical level and the wife to the lower (Howitt 1904: 177). Another qualification seems to be that, in the case of a man who marries his BDD (who is a nadada to him), he has to be ngatata to his brother (niyi), i.e. he has to be categorically the younger brother of his wife’s mother’s father (Howitt 1904: 177).

Figure 7 Elkin’s representation of the Dieri relationship terminology (Elkin 1931: 497)

Concerning this trait of the Dieri system, Elkin writes:

just as I can marry the daughter’s daughter of the kanini who is my mother’s mother’s brother, so too I may marry the daughter’s daughter of this kanini, that is my mother’s mother’s brother’s son’s son’s daughter’s daughter. . . . Professor Radcliffe-Brown has previously suggested that this was the type of grandchild who would be married according to most systems of the Aranda type, including probably the Dieri. She is the daughter’s daughter of a moiety brother, and it is customary for a man to marry a woman so related to him (Elkin 1938: 60).

As I said above, marriage with a nadada of a lower genealogical alternate level is consistent with the Dieri mode of classification, but this category did not include the MMBSSDD (who was in fact a kami to Ego) nor was the MMBSSDD included in the same category as BDD. In the Dieri relationship terminology the specifications of nadada are, in fact, MMBDD at Ego’s level, and BDD or MBDDDD in the second descending level, as a consequence of the four matrilines and the alternation by genealogical level. On this point Elkin confuses the identification of categories in alternate levels derived from a terminology with four patrilines, as in the Aranda, with that derived from four matrilines, as in the Dieri.

Elkin’s report of the moiety system and the matrilineal totemic clans is entirely consistent with Howitt’s account, but Elkin adds some relevant information regarding the role of the father among the Dieri. According to him, the Dieri considered that a child inherited his flesh and blood from his mother but still maintained a close and important relationship with his father. It was the father who cared for the child, was head or senior of the local group to

which the child belonged, and was very much concerned with the initiation of his son or the marriage of his daughter, but what was more important, says Elkin, is that the father’s cult totem was passed on to his fully initiated son. It included a sacred and secret complex of mythology, site, and ritual (Elkin 1931: 497).

VI

Lévi-Strauss’s analysis of the Dieri system is based on Elkin’s report of their relationship terms. From the rest of the literature on the Dieri he only mentions, apart from Elkin’s works (1931, 1940), two works by Radcliffe-Brown (1914, 1931). There is not in his analysis any reference to Gason, Howitt, or any of the earlier ethnographic reports (cf. below, Appendix).

He considers as the relevant characteristics for an appraisal of the system the fact that the Dieri possessed:

1 matrilineal moieties,

2 matrilineal totemic clans,

3 no apparent sections or subsections,

4 a rule of the Aranda type (prohibition of marriage between first cross-cousins and ‘preferential marriage between the four types of second cousins descended from cross-cousins’),

5 reciprocal terms between members of the second ascending generation and the second descending generation,

6 FFZ and MFZ are classified with, or may actually be, FMBW and MMBW respectively (Lévi-Strauss 1949: 256).

Although characteristics (4), (5), and (6) are consistent with an Aranda system, Lévi-Strauss gives the following facts as the main differences between this system and that of the Dieri:

7 cross-cousins are classified with FM and FMB (kami),

8 MMB ≠ MMBSS (kanini and niyi respectively, while the Aranda have just one term for both),

9 there are only sixteen terms (and ‘this has no correlation whatsoever with the Aranda terminology or with the Kariera terminology or with the figure which might be calculated, on the basis of these two last, for a simple moiety system’ [Lévi-Strauss 1949: 256]).

Looking at Elkin’s table, says Lévi-Strauss (1949: 256), it is clear that one cannot regard the Dieri system as an Aranda one, and he then remarks that certain identifications are possible, namely:

10 tidnara — taru (by marriage),

11 ngatamura = paiera (by marriage),

12 ngatata = yenku (‘passing through’ kaku, yenku’s sister and kami’s wife).

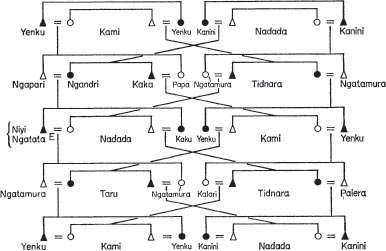

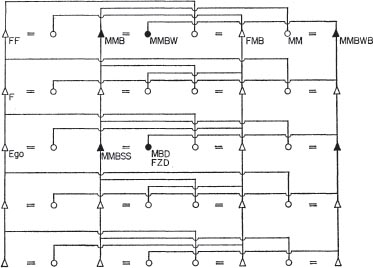

Figure 8 Lévi-Strauss’s ‘simplified’ representation of the Dieri system (1949: 260, Figure 40)

From these data, Lévi-Strauss presents first a ‘simplified’ representation of the Dieri system consisting of four patrilineal lines and restricted exchange between children of cross-cousins (see Figure 8). He finds in this diagram, however, a series of anomalies, which indeed he attributes to the system. He tries to answer then: (i) whence the dichotomy preventing marriage of first cross-cousins arose,6 and (ii) how the terms yenku, nadaday kami, and ngatamura ‘circulate’ through several lines.

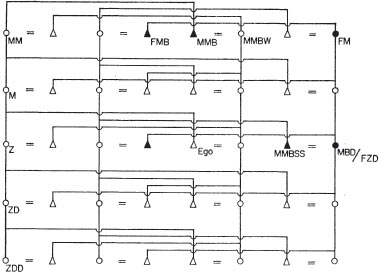

In an attempt to solve these problems he proposes as a working hypothesis the following possible evolution of the system (Figure 9). In addition to this, Lévi-Strauss considers the Dieri system as having changed from a ‘harmonie’ regime and a ‘matrilateral’ system (1949: 275) to its present-day form, ‘an apparent form of eight subsection structure’, under the influence of disharmonie regimes. In the present-day form of the Dieri system ‘the patrilateral and the matrilateral systems act concurrently’ (1949: 275).

VII

In 1962, Lane and Lane, in a paper dealing with the problem of implicit double descent, reconsidered Radcliff-Brown’s interpretation of the Dieri system as a system of double descent.

They point out (p. 50) that Radcliffe-Brown’s claim of double descent for the Dieri, based on the notion of double clan affiliation, is unacceptable according to the available ethnography. Elkin has repeatedly pointed out, they say, that the ceremonial totem called pintara (which Radcliff-Brown takes as the ‘patrilineal clan’) has nothing to do with marriage. But they claim that the Dieri system can still be considered as a system of double descent ‘in the sense of the occurrence of implicit patrilineal moieties intersecting the matrisibs’ (1962: 50). Although they do not present an analysis of the Dieri terminology, they state that it is consistent with an arrangement by which:

a man and his mother’s mother’s brother (alternating generations within a matrisib) marry women of one group, while mother’s brother and sister’s son (adjacent generations to Ego in his matrisib) marry women of a different group (Lane and Lane 1962: 50).

They then claim that:

the result of differentiating adjacent generations and equating alternate generations in a given matrisib on the basis of the matrilineal affiliation of the father is to create two implicit patrilineal moieties intersecting all the matrisibs of the system (1962: 50).

However, ‘these patrilineal cycles received no overt recognition’.

There are at least two points to consider here: (1) what is the relevance of a concept such as an ‘implicit intersecting moiety’, and (2) what exactly is the meaning of ‘matrisib’ in Lane and Lane’s article.

On page 47 of their article they state that ‘by intersecting moiety’ they mean ‘a dichotomous division which bisects every component sib of the society’. Among the Dieri, the ‘patrilineal cycles received no overt recognition’, so they constitute ‘implicit patrilineal moieties’. It is possible to apply to their argument the same sort of criticism that they apply to Radcliffe-Brown’s interpretation: among the Dieri there is no recognition of any patrilineal principle in relation to marriage. What the Dieri have is a rule that prescribes marriage with the category nadada and it is the particular conformation of their relationship terminology which has the effect that men belonging to the same matrilineal line but to alternate levels marry in the same line of the opposite moiety. To call this consequence of the constitution of the relationship terminology an ‘implicit patrilineal moiety’ or to call it ‘implicit patrilineal clans’ does not make any difference: neither of these phrases corresponds to any actual institution in Dieri society or to any principle that the Dieri apply in their particular mode of classification.

As for the ‘sibs’ which these ‘patrilineal moieties’ intersect, are they matrilineal terminological lines or actual matrilineal institutions such as, for example, the matrilineal totemic groups? It seems that for Lane and Lane they are actual matrilineal institutions; otherwise, the phrase ‘the Dieri kinship terminology was consistent with their system of matrilineal sibs’ (1962: 50) would be a tautology. The Dieri, however, did not marry a person because she or he belonged to a certain ‘matrilineal sib’, but because she or he was in a certain categorical relationship (nadada) to them. The distinction between marriageable and non-marriageable people was based upon a terminological distinction, and membership of a certain matrilineal totemic group was only a secondary device specially useful in cases of marriage between people belonging to different tribes.

VIII

At this point we may revert to Lévi-Strauss’s account of the system. It will be remembered that he isolates certain characteristics as evidence of the systematic difference between the Dieri and the Aranda forms of organization. Let us consider first those characteristics which we have listed as (7) and (8), namely, cross-cousins are classified with FM and FMB (while among the Aranda they are classified with MMBW); MMB ≠ MMBSS (kanini and yenku respectively, while the Aranda have just one term for both).

From the point of view of the configuration of the relationship terminology, what is meant by an ‘eight-section system’ is a prescriptive terminology that consists of four lines and expresses a rule by which the category that contains the genealogical specification of second cross-cousins is prescribed. This factor is revealed by the repetition of the same term in alternate levels within a single line. Thus, if one considers a terminology that contains patrilines, the diagram that can be drawn is as follows (cf. Figure 10). In a terminology of this kind, it is perfectly clear why the category that contains the specification of first cross-cousin is designated by the same term as the category genealogically specified as mother’s mother’s brother’s wife and her brother. The categories belong to the same terminological line and to alternate genealogical levels. The same can be said about the category that contains MMB and the one that contains MMBSS: there is no need for more than one term for both because they belong to the same terminological line in alternate genealogical levels.

Figure 10 Diagram of a four-line symmetric prescriptive terminology (patrilines)

If, instead of being based on patrilines, a four-line symmetric prescriptive terminology is based on matrilines, the diagram is the following one (see Figure 11). In a terminology of this sort, the category that contains the specification of first cross-cousins does not belong to the line containing the specification for MMBW, but to the line to which the specifications of FM and FMB belong. On the other hand, MMB and MMBSS are contained in categories that do not belong to the same terminological line either.

If the Dieri terminology differs from an ‘Aranda terminology’ in the points Lévi-Strauss indicates (and which we have numbered as 7 and 8), this could be due to the fact that what is meant by an ‘Aranda terminology’ is a terminology based on four patrilines, whereas the Dieri terminology is probably based on four matrilines. This is the first consideration we are going to take into account in our analysis of the system.

Figure 11 Diagram of a four-line symmetric prescriptive terminology (matrilines)

Figure 12 Dieri relationship terminology (according to Elkin’s list of terms, cf. Table 5)

Let us then see whether the Dieri terminology is consistent with a four-line symmetric prescriptive terminology based on matrilines. Taking into account Elkin’s list of terms, the resulting diagram is as shown above (see Figure 12). Looking at the diagram it is possible to distinguish the following features:

(i) there are four matrilines headed by the terms yenku, FFZ (1); kami, FM (3); nadada, MFZ (2); and kanini, MM (4);

(ii) in each line these four terms are applied in alternate genealogical levels (only in Ego’s line at Ego’s level o there are distinctive terms for older and younger brother and for older and younger sister, but these are common features in lineal terminologies);

(iii) in the first ascending and the first descending genealogical levels the term tidnara (9) designates the category of persons who belong to the same moiety as Ego and who do not belong to the categories F, M, FZ, MB. The term taru (10) denotes affinal status: it designates the actual WF, who is genealogically tidnara to Ego, in the first ascending genealogical level, and also the category of marriageable persons for Ego’s children in the first descending genealogical level (in other words, persons of the first descending genealogical level who belong to Ego’s moiety but not to Ego’s line);

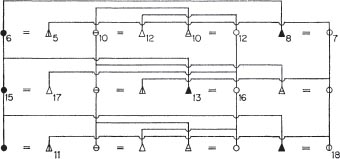

(iv) setting aside exceptions to be enumerated below, the basic differentiations between categories are made according to genealogical line and level, but not according to sex. The exceptions to this rule are found in only the first ascending and the first descending levels, as shown in Figure 13.

(v) as we noted above, tidnara-taru, ngatamura-paiera, nadada-noa, and nadada-kadi, in the first ascending and in Ego’s genealogical level, are terms denoting respectively, in each pair, potential and actual affines in these positions.

Let us consider the formal diagram employed above (Figure 11) to represent a four-line symmetric prescriptive terminology, and then relate the features of the Dieri relationship terminology to that diagram.

The diagram is composed of two divisions, each of which contains two lines. There are in the diagram two kinds of connection: vertical connections between points located in each level, and horizontal connections between the points of each line with points located in the lines of the other division. Considering a single line, the points at alternate levels are connected by equation signs with points of a single line of the other division. Each line is composed of two kinds of signs, namely a circle and a triangle, in each level.

Figure 13 Categories of the same genealogical level and line differentiated by sex (according to Elkin’s list of terms, cf. Table 5)

Each of these elements has a correlate in a four-line symmetric prescriptive terminology. The vertical lines correspond to terminological lines, each point in a line corresponds to a genealogically definable term, each level to a genealogical level; each equation sign corresponds to a genealogically necessary connection between terms; circle and triangle correspond to terms of the same line and the same genealogical level defined genealogically as siblings of opposite sex. Operationally one can define a four-line symmetric prescriptive terminology as a terminology the elements of which conform to a diagram such as that described above.

The characteristics numbered (i) and (ii) of the Dieri relationship terminology show that it contains the main indicators of a terminology as defined above. There are four matrilines and in each of them the terms corresponding to Ego’s genealogical level are repeated in the second ascending and the second descending genealogical levels within the same lines. In order to analyse the first ascending and the first descending genealogical levels, it is necessary to take into account that, to be consistent with the diagram we are considering, the terminology ought to possess a clear indication that each line is related to the line in the other terminological division which does not contain the terms to which those of Ego’s line are related at Ego’s level and at the second ascending and descending genealogical levels. Looking at the diagram representing the Dieri terminology (Figure 12) it is possible to see that there is an indication of that sort denoted by the following facts: (a) the terms employed in the first ascending and the first descending levels do not repeat any of the terms of the other levels; (b) the four lines are constantly distinguished; and (c) each line is related to the line of the opposite terminological division where the terms of the genealogical level previously considered are not related.

Although the Dieri terminology is, as we have seen, entirely consistent with the diagram representing a four-line symmetric prescriptive terminology, it could be said that it is not consistent in the most economical possible way. The differentiations by sex in the first ascending and the first descending genealogical levels are not necessary if one considers the logic of the diagram itself. The explanation, therefore, is not to be found by looking at the diagram and the relations and differentiations it implies. If the explanation is not to be found in the logic underlying a totally formal analysis of the terminology, it presumably lies in the relationship between the mode of classification represented by the terminology and the actual rules and the social forms coexisting with the terminology in Dieri society.

Before going on with the analysis let us make some assumptions explicit. Terminologies represent modes of social classification which are susceptible of analysis according to entirely formal criteria, such as (a) linearity/non-linearity, (b) prescription/non-prescription, (c) symmetry/asymmetry. These criteria are the formal consequences of basic principles of classification which can be applied, systematically or not, to different analytical spheres of social organization. If the principles are consistently applied, one is likely to find systematic correspondences between any two possible spheres. In the Dieri case, the terminological divisions actually correspond to the exogamous moieties. The correspondence, nevertheless, does not permit the inference of any causal connection between the two spheres, mainly because if there is a causal connection it is not a necessary one. This is demonstrated by the fact that (i) there are societies that possess a terminology divided symmetrically and do not possess exogamous moieties (as in the case of Sinhalese society [see Leach 1960: 124-5]); (ii) there are societies that possess exogamous moieties and do not have a symmetric terminology (as in the case of Mota society [see Needham 1960d: 23-9; 1964b: 302-14]).

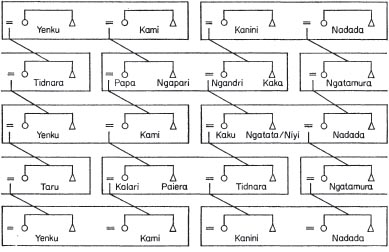

These considerations lead to two basic issues in the discussion of the relationship between terminologies and other spheres of social organization, namely: (a) the relationship between symmetric prescriptive terminologies and the existence of ‘marriage classes’ (viz. moieties, sections, and subsections), and (b) the relationship between terminological differentiations that are not logically related to any specific form of terminology but to rules or social forms coexistent with them.

Considering the Dieri terminology and Dieri social forms, the exogamous moieties permitted a classification of Dieri individuals that was entirely consistent with the classification derived from the terminological divisions. But there did not exist in Dieri society, so far as can be seen from the ethnographical reports, any social forms comparable with the exogamous moieties and consistent with the terminological classification into four lines. In other words, there were neither subsections nor any other form of actual institutions corresponding to the four lines in the terminology. The non-existence of subsections has, nevertheless, nothing to do with the formal definition of the Dieri terminology as a four-line symmetric prescriptive terminology.7 All that can be said in this respect is that there is no correspondence between the terminological classification of persons into four lines and a particular correlated set of social institutions. This fact did not prevent the Dieri from having a rule of marriage consistent with a classification into four terminological lines. The rule was based on categorical distinctions, and the whole system worked like an ‘eight-subsection system’, only these subsections are not a necessary concomitant of the four lines and the rule of marriage.

In the case of the differentiations by sex in the first ascending and the first descending genealogical levels of the Dieri relationship terminology, we are confronted with a problem of a different kind. Those differentiations are not necessary formal features of a four-line symmetric prescriptive terminology. They cannot be derived from the logical configuration of such a terminology. Instead, they can be related to rules and institutions of Dieri society.

The differentiation between the genealogical specifications of mother and mother’s brother (ngandri and kaka) and between those of father and father’s sister (ngaperi and papa), although both pairs of terms contain categories belonging to the same terminological line, is a common trait of lineal terminologies and is probably accounted for by the special roles of the people categorized as such regarding Ego. Ngandri is the term that denotes the actual mother, her sisters, and all the women of the same line and genealogical level as these (they are ngandri-waka for Ego, cf. Howitt 1891: 45-9).8 They are the women of Ego’s exogamous totemic group, and probably most of them live in the same patrilocal group as Ego. They are all of them ‘same flesh and blood’ as Ego. This also applied to individuals categorized as kaka (MB, FZH), but they certainly lived in a different local group, because locality was decided patrilineally. On the other hand, individuals categorized as kaka had an important role concerning Ego’s marriage: one of them was, together with Ego’s actual ngandri, M, the person who arranged Ego’s betrothal and they were also the fathers of Ego’s kami (the prohibited category).

The women categorized as papa (father’s sisters) were the mothers of Ego’s kami. They were same ‘flesh and blood’ as Ego’s father and they lived in the same local groups as Ego’s kaka, MB. Whether kami was the prohibited category because the women categorized as such were ‘same flesh and blood’ as Ego’s ngaperi, F, and therefore a patrilineal principle was added to the matrilineal inheritance of ‘flesh and blood’, or whether the prohibition of marriage with a kami was borrowed by the Dieri from neighbouring societies,9 so that the distinction between ngaperi and papa could be seen as a functional one regarding that prohibition, it is impossible to know. Durkheim would doubtless have explained the prohibition to marry a kami as a result of matrilineal descent and patrilineal residence: Ego’s kami lived in the same local groups as Ego’s kaka (MB) and thus were ‘too near’ to Ego because they were ‘too near’ to Ego’s matrilineal totemic ceremonies (Durkheim 1898:18-19; 1902:100-12; see Figure 14). Although this explanation does not apply to other systems presenting similar characteristics (such as the Aranda and the Mara), it is plausible for the Dieri. The distinctions between ngandri (Μ, MZ) and kaka (MB), and between ngaperi (F, FB) and papa (FZ), were probably useful for the Dieri in considering the people involved in the betrothal and regarding the prohibited category (kami).

Figure 14 Hypothetical distribution of Dieri categories among local groups (according to Elkin’s list of terms, cf. Table 5)

The terms in the first descending genealogical level are more difficult to explain. According to Elkin’s diagram the set of terms for this level is composed of: tidnara, ZS, ZD (9); taru, SW, DH (10); ngatamura, S, D (12); paiera, ZDH (11);and kalari, ZSW (18).

The first puzzling feature is the application of the term tidnara (which in the first ascending genealogical level belongs to the yenku line) to positions in the kanini line at this level (cf. Table 6). Why is there this change of line in this particular genealogical level, if there is not any other term that is allocated to more than one line? If the principle of alternation were followed consistently at this level, the terms for the positions concerned (ZS, ZD) would logically be ngandri (M)10 and kaka (MB), i.e. the terms denoting the same positions in the first ascending genealogical level. But there is no doubt that these terms are not repeated in the first descending level, and, furthermore, the term tidnara is specified as ‘nephew’ by Gason (1879), as ZS by Vogelsang (in Howitt 1891), as ZS by Flierl (in Howitt 1891), and again as ZS and as FMBS by Berndt (1953). That is to say, all the specifications in the different reports coincide with that given by Elkin (cf. Appendix to this chapter). If these are the facts, one has to think that either (i) the term tidnara is actually applied to different lines in the first ascending and the first descending genealogical levels (yenku and kanini lines respectively), or (ii) the term applies to all positions corresponding to Ego’s moiety and the first descending level. This second point is a mere assumption based on the fact that at Ego’s level the positions belonging to the yenku line are denoted by the term yenku, with the addition of kaku (eZ) and niyi (eB). As all the positions belonging to Ego’s terminological division and genealogical level are distinguished by the terms kaku and niyi, it seems plausible that the children of the persons belonging to these categories (categories of Ego’s moiety) are all categorized as tidnara (ZS, ZD).

Table 6 Dieri relationship terms by genealogical level (according to Elkin’s list, cf. Table 5)

On this assumption, the term taru (SW, DH) in the same genealogical level (first descending level), would denote an actual affinal status, as it certainly does in the first ascending genealogical level (WF, WFZ). But, taking into account these considerations it would not be easy to understand how the Dieri reckoned between marriageable and non-marriageable categories for the people classified in their own terminological division at that level. After all, they were concerned with the betrothal of people of that first descending level (the children of their sisters).

A second assumption is possible, and it refers to the distinction of the supposed tidnara of the first descending genealogical level according to whether they were the children of a kaku or of a kaku-yenku. They were concerned with the betrothal of the tidnara children of a kaku. The potential spouses of their children would then have been the tidnara children of their kaku-yenku.

In the same genealogical level, there is no problem with the term ngatamura (12), the specifications of which are S and D, and which is applied to the alternate positions in the first ascending and the first descending genealogical levels.

But the remaining terms, paiera (ZDH) and kalari (ZSW), introduce more problems. Paiera (11) is applied in the first ascending genealogical level to the actual mother of Ego’s wife. It therefore denotes the mother of a nadada, the Ego’s actual noa. But it is also applied to the brother of Ego’s wife’s mother. In the first descending genealogical level it is applied (as in the case of tidnara) to a position that belongs to another line. But the change of line can be explained by the change of line of the term tidnara. In the first ascending genealogical level, a paiera man is the actual husband of a tidnara. In the first descending genealogical level, paiera are again the actual husbands of some of Ego’s tidnara (ZD). On the other hand, Ego is in the same relation to the paiera of the first ascending genealogical level as the mother’s brother of Ego’s wife, and Ego is the mother’s brother of the wife of the paiera in the first descending genealogical level. Considering the rules of betrothal among the Dieri, the paiera of the first ascending genealogical level is involved in Ego’s betrothal, as Ego is involved in the betrothal of the paiera in the first descending genealogical level. Paiera could then be a reciprocal term for all these positions related by the betrothal of the sister’s children.

The term kalari, ZSW (18), is uniquely applied to one position in the first descending genealogical level of the kami line. It is, together with ngaperi, F (5), ngandri, M (6), kaka, MB (8), and papa, FZ (7), one of the small set of terms each of which is applied to only one position. The problems to explain with regard to this term relate to line and level: (i) why there is a distinct term in the kami line to denote this position, instead of a repetition of the term papa; and (ii) why there is a distinction by sex between paiera and kalari (ZDH and ZSW respectively) if this distinction does not apply to any other pair of positions at this genealogical level. Looking at Howitt’s and Elkin’s definitions of the term kalari, one finds that they give two different specifications: Elkin defines kalari as ZSW (m.s., by the convention of the diagram), but Howitt specifies the term as SW (w.s.). Considering that paiera is a reciprocal term, so that Ego is paiera to his ZSW and to his ZSH, and his ZDH is paiera to him, it seems that the logical term for the position of ZSW should be paiera also. The ethnography provides no means of resolving this issue.

IX

Going back now to the ‘similarities’ and ‘disparities’ pointed out by Lévi-Strauss between the Dieri system and an ‘Aranda terminology’, it is possible to see that the features signalized as common to both systems, namely:

(5) reciprocal terms between members of the second ascending and the second descending genealogical levels; and

(6) FFZ and MFZ classified with FMBW and MMBW respectively,

are two of the basic traits of a four-line symmetric prescriptive terminology. On the other hand, the dissimilarities between the two systems which Lévi-Strauss indicated, namely:

(7) cross-cousins are classified with FM and FMB (kami); and

(8) MMB ≠ MMBSS,

are basic features of a terminology of that kind based on matrilines.

There still remains the consideration of the number of terms. Lévi-Strauss says that the Dieri have only sixteen terms and ‘this has no correlation whatsoever with the Aranda terminology or with the Kariera terminology or with the figure which might be calculated, on the basis of these two last, for a simple moiety system’ (Lévi-Strauss 1949: 256). When considering the logic of a diagram representing a four-line symmetric prescriptive terminology we showed that a terminology consistent with that diagram could have even fewer than sixteen terms. In the analysis, we were also able to see that the number of terms of any terminology does not depend only on the distinctions that make it possible to define the terminology according to a diagram (cf. Needham 1963:228), but also on distinctions that refer to other levels of analysis. In the type we are describing, the diagnostic features are given by the distinction of four lines and the identifications in alternate genealogical levels. Distinctions according to sex are irrelevant to the formal definition of the type, and empirically (in this case) they occur in the first ascending and the first descending levels (on the assumption that Elkin’s specification of kalari, ZSW, is correct), and they can be related to facts and rules belonging to other spheres of social organization.

There is no specific number of terms related to a specific type of terminology, as there are no specific social forms necessarily related to the different types of social classification. Concerning the number of terms, one could indicate what is the minimum for a certain definite type. Concerning social forms, such as moieties, sections and subsections, or types of local groups, one can only indicate whether they exist or not in a particular society, and, when they do, whether they are consistent or not with the classification provided by the relationship terminology.

If the Dieri had a system of social behaviour consistent with their relationship terminology (and the evidence demonstrates that they had), this would show that such a system does not necessarily imply subsections. The Dieri could distinguish individuals categorically, and not by their membership of actual institutions such as subsections.

A terminology can be classified, therefore, by its formal features. One can establish systems of social action consistent with a particular mode of social classification and prove empirically whether or not there is correspondence between both spheres.11 Considering the terminology from a formal point of view, the diagram to which one relates a set of terms is a consequence of the application of certain basic principles. We call ‘basic principles’ the criteria by which categories are distinguished, and these criteria could be genetically related to certain basic forms of empirical organization and the transmission of rights from one generation to another.

Lévi-Strauss’s idea of relating systems of ‘restricted exchange’ to ‘disharmonie regimes’ is, as we have already seen in chapter 2, a reformulation of the explanation Durkheim gives for section systems. For Durkheim, a section system is a result of patrilocal residence and matrilineal descent (Durkheim 1898: 18-19). For Lévi-Strauss, patrilocality and matriliny are the indicators of ‘restricted exchange’ (Lévi-Strauss 1949: 271). The difference between the two hypotheses lies in the fact that, while one is an explanatory hypothesis concerning a particular type, the second proposes an empirical correspondence between systems and regimes. Durkheim relates the existence of four-section systems to the separation of adjacent generations within a single local group, because adjacent generations in a patrilocal group belong to different matrilineal moieties, but living together they are ‘too near’ each other to be allowed to intermarry.12

Following Durkheim’s idea, a four-line symmetric prescriptive terminology could respond to the separation of people belonging to opposite lines but living in the same local group. If the Dieri were divided into exogamous matrilineal moieties and residence was patrilocal, in order to avoid marriage with people who were ‘too near’ their own line (or their own matrilineal totem) because they lived in the same local group with individuals of their own line (as in the case of kaka‘s children, MBC), they could devise another line in the opposite moiety. In this way, individuals from a single line and consecutive genealogical levels would marry in different lines of the opposite moiety. That is to say, they married in the line where their mothers and mother’s brothers did not marry and in a different local group. This fact accounts for the identifications in alternate genealogical levels and for the prescribed category. The resulting system might be considered as the result of the concurrence of a matrilineal principle and the creating of ‘implicit patrilineal moieties’ (Lane and Lane 1962: 50), but the only principle that seems to be applied in Dieri society is a matrilineal principle in a patrilocal society. What the Dieri people perhaps had in mind was not to marry a kami because their kami lived in the same local group of the people of their own exogamous totemic group and their own line, and this was probably the cause of distinguishing another line in the opposite moiety.

Why then recognize another line in their own moiety? Presumably because their own children belonged to the opposite moiety and therefore married in Ego’s moiety, within which concordant distinctions needed to be made.

For the sake of clarity we have given a hypothetical genetic evolution of a four-matriline symmetric prescriptive terminology, assuming the existence of actual exogamous moieties. We have proceeded in this way because the Dieri terminology is our example and the Dieri actually possessed exogamous matrilineal moieties. But the same reasoning could be followed starting with a hypothetical case of a two-line symmetric prescriptive terminology based on matrilines in a society with patrilocal residence. Only in the case of a mode of classification such as that of the Dieri, the concomitant system of actual behaviour is complicated enough to make us think that they had to make use of definite social institutions (in this case exogamous moieties) in order to make it simpler. If our assumption is correct, it can then be imagined that the Dieri might have created eight subsections in order to reinforce their mode of classification; but, if so, they certainly would not have needed to start with the creation of four sections.

Our point is that one does not need to think that because a ‘four-section’ system has four sections and an ‘eight-section’ system has eight subsections, and because 8 is a multiple of 4, there is therefore ‘a genetic relation between eight-section and four-section systems’ (Lévi-Strauss 1962a: 74). If, however, one is ‘tempted’ to interpret moiety, section, and subsection systems according to the ‘natural “order”: 2, 4, 8’ (Lévi-Strauss 1962d: 54), one is bound to consider the Dieri system as a case of ‘apparent form of eight-section structure’ (Lévi-Strauss 1949: 275), and to give as a possible evolution of the system the change from ‘generalized exchange’ to ‘restricted exchange’ (Lévi-Strauss 1949: 275).

How to justify such a hypothesis if the Dieri relationship terminology is one of the neatest examples of a four-line symmetric prescriptive terminology, and if the genetic principles for such a mode of social classification are seen as the concurrence of matrilineal descent and patrilocal residence?

The justification lies, for Lévi-Strauss, in a diagram which does not correspond to the Dieri relationship terminology (cf. Lévi-strauss 1949: 260, Figure 40).13 Lévi-Strauss understands the Dieri relationship terminology to be based on four patrilines and the diagram he presents corresponds to this conception. He then asks ‘whence does the dichotomy preventing the marriage of cross-cousins arise?’14 because it seems to be ‘a sort of needless elaboration’, and ‘how it is that the four terms yenku, nadada, kami and ngatamura circulate through several lines?’ (Lévi-Strauss 1949: 257). Posed in this way the questions are not easy to answer, and Lévi-Strauss demonstrates this by giving the possible evolution of the system as ‘firstly, an archaic system with four matrilineal and matrilocal lines based on generalized exchange . . .; secondly, the adaptation to a Mara – Anula system; and, finally, the present system’ (Lévi-Strauss 1949: 262). He adds, moreover, that even if this is a purely hypothetical sequence, it is ‘the only one allowing the anomalies of the system to be understood’.

Looking at the Dieri relationship terminology as based on matrilines, however, it is clear that the terms yenku, nadada, kami, and ngatamura do not at all ‘circulate through several lines’ but that they are systematically applied to alternate genealogical levels, each within a single line. We hope we have demonstrated that there are no such anomalies to be understood.15

Lévi-Strauss’s interpretation seems to be based on his belief in a genetic connection between ‘four-section’ and ‘eight-section’ systems, and on the consideration of systems with an ‘Aranda rule’ but without subsections as anomalous and deriving from ‘generalized exchange’. Our analysis, by contrast, is based on the formal analysis of relationship terminologies, and on the discrimination of two kinds of symmetric prescriptive terminologies: those based on two lines and those based on four (whether patrilines or matrilines). ‘Four-section’ systems would thence be considered as systems possessing a two-line symmetric terminology (see Needham 1966: 142 n. 2), and the possible explanation for the existence of the four sections accounts also for the existence of symmetric prescriptive terminologies based on four matrilines.

1 This is not the only system to which Lévi-Strauss ascribes peculiar characteristics, but it is one of the more revealing for the study of his method.

2 cf. Needham’s analysis of Wikmunkan society (1962b).

3 For direction to published sources I have relied in the first place on John Greenway’s Bibliography of the Australian Aborigines and the Native Peoples of Torres Strait to 1959 (1963). This excellent guide was supplemented by titles furnished by Mrs B. Craig, Research Officer, Bibliographical Section of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, who very kindly and efficiently offered further advice on Dieri sources. The Information Officer at Australia House, London, was good enough to provide a photographic copy of Mant’s paper (1946). Pastor W. Riedel, Dr T. G. H. Strehlow, and Dr D. Trefry kindly responded to my queries, and Professor A. P. Elkin made many observations from his own point of view on the theoretical framework of this chapter. I am most grateful for the help thus received.

4 In this case, the legend demonstrates that the Dieri did not think of their moieties only in terms of the regulation of marriage. The possibility of their preexistence to their function as exogamous groups shows that their primary function was other than exogamy. Moreover, it demonstrates that sections or moieties could be a convenient division for the purposes of a symmetric system of marriage, but that they are not necessary for the existence of such a system (cf. Elkin 1964: 123; Needham 1960c: 82; 1966: 141).

5 cf. Needham 1960d: 96-101; 1964a: 23.

6 R. Needham points out that, by a slip at some point in the preparation of the English edition, the original d’où, whence, was misrendered as ‘when’ (1969:206).

7 cf. Dumont 1964; Needham 1966, 1967a, 1969, on the relationship between formal features of a terminology and empirical institutions.

8 According to Gatti’s vocabulary (1930), the translation of waka is ‘small’ (‘piccolo’, ‘basso’, p. 115).