Some Comments on Alternation:

the Mara Case

I

The Aranda, the Dieri, and the Iatmül terminologies have in common the following features: all of them are lineal; in all of them there is an alternation of terms in each line; and in all of them the prescribed category is genealogically specified as second cross-cousin (MMBDD, FFZSD, FMBSD, MFZDD).

We have so far considered Durkheim’s hypothesis on the relationship between alternation and the concurrence of patrilocality and matrilineal descent, and Lévi-Strauss’s reformulation of this hypothesis in terms of disharmonic regimes and symmetry.

From the three cases studied the only one that is consistent with such hypotheses is the Dieri, because this system is patrilocal and has matrilineal moieties and matrilineal exogamous clans. The Aranda and the Iatmül, however, cannot be explained by the same hypothesis. In the Aranda case, there are patrilocal groups, patrilineal affiliation to the four sections or the eight subsections, and a terminology composed of four patrilines. In the Iatmül case, there are patrilineal clans, patrilineal non-exogamous totemic moieties, patrilineal ceremonial moieties, patrilocal groups, and five patrilines in the terminology.

Patrilocality and matrilineal descent cannot therefore be considered to stand in any necessary relationship to alternation.

Dumont and, following him, Sperber, have latterly proposed an alternative explanation for this sort of system. We shall analyse this in the last section of the present chapter.

Lévi-Strauss also proposed another possible evolutionary sequence in the formation of alternating systems, but in his case it was not because he rejected his former proposal on the relation between regimes and structures. His second hypothesis about the factors producing alternation is, as we shall now see, complementary rather than alternative to the first.

II

For Lévi-Strauss, ‘the system of alternate generations does not result exclusively, or necessarily, from bilateral descent. It is also an immediate function of patrilateral marriage’ (1949: 254). Also: ‘patrilateral marriage systems and disharmonic regimes are both of the alternating type’ and ‘this alternating type, which is common to both, makes the transition from the patrilateral systems to the formula for restricted exchange easier than it is for matrilateral systems’ (1949: 275).

None of the three systems we have already considered seems to have evolved from a patrilateral system (marriage with the category specified as FZD). None of them can be characterized, either, as possessing ‘bilateral’ – i.e. bilineal – descent. Only the Dieri can be classified as having a ‘disharmonic regime’. The Aranda and the Iatmül certainly function according to a ‘harmonic’ regime.

But for Lévi-Strauss the case that illustrates the passage from a patrilateral system to a ‘formula of restricted exchange’ is the Mara system.

The Mara are, he says, one of the group of tribes that have ‘a kinship terminology of the Aranda type, but with only four named divisions. . . . The son remains in his father’s division, and this gives the four divisions the appearance of patrilineal lines grouped by pairs into two moieties’ (1949: 248). Radcliffe-Brown and Warner, says Lévi-Strauss, ‘have tried to bring the social structure and the kinship terminology into harmony’ (1949: 248-9) because they considered that the four divisions of the Mara are four ‘semi-moieties’ consisting each of two groups which are equivalent to subsections among the Aranda. But for Lévi-Strauss, ‘the question must be asked whether the Mara system . . . should not be interpreted . . . as a system effectively with four classes and a borrowed Aranda-type terminology’. In support of this argument he says that ‘if the Mara system differed from an Aranda system only in that subsections were unnamed, the rules of marriage would be strictly identical in both. But this is not so’ (1949: 249).

Lévi-Strauss bases this statement on the fact that, in addition to their rule of a normal Aranda type, there is an alternative marriage formula in the Mara-type systems studied by Sharp in Northwestern Queensland. Lévi-Strauss notes that the Laierdila system of the islands and coast of Queensland, studied by Sharp, are ‘of the Mara type’ but that it has two additional marriage possibilities, one with the mother’s brother’s son’s daughter, and the other with the father’s father’s sister’s daughter. For the Laierdila, then, ‘it is . . . possible for an A1 man to marry a woman of any of the subsections B1 B2, C1 C2 or any woman of the moiety opposite to his own’ (Sharp 1935: 162). He notes then that ‘the question arises seriously whether the Mara system . . . should not. . . be considered as a four-class system with patrilateral marriage, . . . expressed in terms of an Aranda-type system’. Also, ‘the Mara system, because it has kept to its primitive structure, has had to allow its patrilateral orientation to be submerged in the apparently bilateral form of its alternate marriage, which is of the Kariera type’ (1949: 251). Therefore, ‘until more information is available, the Mara system should not be regarded as an Aranda system which has lost some of its superficial characteristics, but as an original and heterogeneous system upon which Aranda features are gradually being superimposed’ (1949: 252).

III

The Mara were included by Spencer in the category of ‘tribes with direct male descent’. He describes them as having a system composed of two patrilineal moieties, Muluri and Umbana, each of which is subdivided into two ‘classes’. These named ‘classes’ are Murungun and Mumbali, in the Muluri moiety, and Purdal and Kuial, in the Umbana moiety. ‘Though there are no distinct names for them, each class is really divided into two groups – the equivalent of the subclasses in the Aranta and Warramunga. They are, in fact, precisely similar to the unnamed groups into which each class is divided in the southern half of the Arunta and in the Warrai tribe’ (Spencer 1914: 60-1). According to Spencer, each of the subdivisions of the four named divisions can be distinguished by the letters α and β, so that the intermarrying groups and the classes of the children can be represented as follows (see Table 8). The explanation is that a Murungun α man must marry a Purdal α woman and their children are Murungun β. A Purdal α man marries a Murungun α woman and their children are Purdal β, etc.

Table 8 Spencer’s representation of the intermarrying groups among the Mara (Spencer 1914: 61, Table 3)

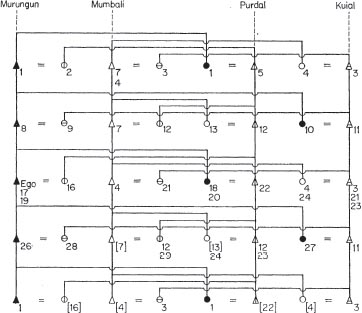

In 1904, Spencer and Gillen gave a detailed account of the Mara relationship terminology (cf. Table 9). According to these authors, the relationship terms are perfectly consistent with the arrangement of the named classes and unnamed subclasses. The diagram in which these terms can be arranged is composed of four lines (see Figure 26).

Figure 26 Mara relationship terminology (Spencer and Gillen 1904: cf. Table 9)

Table 9

Mara Relationship Terms

(Spencer and Gillen 1904)*

| 1. | muri-muri | FF, FFB, FFZ, WFM, SS, SD |

| 2. | namini | FM, FMZ |

| 3. | napitjatja | MF, FFZSWF, DHF, DC |

| 4. | unkuku or kukn | MM, FFZSWF, FFZDC, SWM |

| 5. | nakaka | MMB (w.s.) |

| 6. | umburnati | WFF |

| 7. | tjumalunga | WMF, WMB |

| 8. | naluru | F, FB |

| 9. | katjirri | M, MZ |

| 10. | umburnana | FZ |

| 11. | gnagun | MB, DH |

| 12. | nipari | WF, ZHF, FFZS, FFZD, FMBS, FMBD ZS, ZD |

| 13. | gnungatjulunga | WM, ZHM, FFZSW, FMBSW |

| 14. | yallnalli | HF |

| 15. | niringwinia-arunga | HM |

| 16. | irrimakula | W, WZ, Η, HB |

| 17. | guauaii | eB, FeBS |

| 18. | gnarali | eZ |

| 19. | niritja | yB, FyBS |

| 20. | gnanirritja | yZ, FyBD |

| 21. | nirri-marara | MBC, FZC |

| 22. | mimerti | WB |

| 23. | kati-kati | SWF |

| 24. | gnakaka | DHM |

| 25. | nirri-miunka-karunga | HZ |

| 26. | nitjari | S, BS |

| 27. | gnaiiati | D, BD |

| 28. | nirri-lumpa-karunga | SW |

| 29. | gnaiawati | ZD |

| 30. | tjamerlunga | DH (w.s.) |

| 31. | naningurara | SW (w.s.) |

| 32. | yillinga | SC (w.s.) |

| 33. | gambiriti | SSC |

| 34. | kankuti | DDC |

| 35. | yallnali | SSS (w.s.) |

* Spencer and Gillen 1904: 87, 88, Table of Descent: Mara Tribe (op. p. 87), 130, 131.

Although Spencer and Gillen’s account of the Mara relationship terms is very detailed, it still seems to be incomplete with regard to the specifications of some categories. Yet the arrangement of the terms does not differ from that of the Aranda terms, and the prescribed category (irrimakula) is genealogically specified as MMBDD/FFZSD, i.e. the same as the prescribed category among the Aranda and the Dieri.

A man is betrothed to one or several women who are irrimakula to him. This betrothal is arranged by the father of the woman ‘[telling] a man who stands in the relationship of father’s sister’s son to the individual to whom the former proposes to give his daughter. This telling another man who acts as intermediary is associated with the strongly marked avoidance of son-in-law and father-in-law in the Mara tribe’ (Spencer and Gillen 1904: 77 n. 1). Thus the individuals who arrange the betrothal of a man are nipari (FMBS, WF) and nirri-marara (FZS) to him.

Although it is the ‘general rule’ to marry a irrimakula, there is a further ‘lawful’ wife for a man. A man may marry, namely, a woman who stands in the position of nirri-marara, FZD/MBD, to him, provided she comes from a distant locality (Spencer and Gillen 1904: 126).

IV

Warner’s report on the Mara ‘semi-moieties’ (1933) does not differ from Spencer and Gillen’s account of the Mara ‘marriage classes’. When describing the tribes of the Gulf of Carpentaria and the mouth of the Roper River, he says:

each tribe has four named divisions, but instead of the son being in a different division from his father, as in the normal section systems, he remains in the same group. If the father is P, the son is P. This gives each of the four patrilineal lines a name and creates a condition where there are two named divisions in each tribe.

Marriage is exogamous. Ego cannot marry into his own or the group belonging to his side of the tribe. Not only is he excluded from these two groups, but he cannot marry into his mother’s group of the opposite moiety (Warner 1933: 79).

The list of terms he reports for the Mara is as in Table 10.

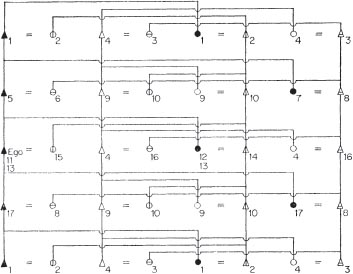

This list is not totally consistent with the list in Spencer and Gillen. There are fewer terms; certain distinctions by sex at the same genealogical level are lacking; there is only one term for yB and yZ against two in Spencer and Gillen, one term for FM and WFF against two in Spencer and Gillen, etc. The spelling also is very different. But, still, this list can be arranged in the same kind of diagram and is even more consistent with it and more economical (see Figure 27).

Table 10

Mara Relationship Terms

(Warner 1933: op. p. 69)

| 1. | mur-ĭ-mur-ĭ | FF, FFZ, SS, SD |

| 2. | mi-mí | FM, FMB, FMBSSSS, FMBSSSD |

| 3. | bí-dja-dja | MF, MFZ, DS, DD |

| 4. | go-go | MM, MMB, MMBSS, MMBSD, MMBSSSS, MMBSSSD |

| 5. | lur-lu | F, FB |

| 6. | kai-djĭr-ri | Μ, MZ |

| 7. | bar-nan-a | FZ |

| 8. | gar-dī-gar-dī | MB, MBSS, MBSD |

| 9. | mu-lor-ī | MMBS, MMBD, MMBSSS, MMBSSD |

| 10. | nī-pal-lī | FMBS, FMBD, FMBSSS, FMBSSD |

| 11. | baba | eB |

| 12. | nua-ru-nur-no | eZ |

| 13. | lĭm-bil'-li | yB, yZ |

| 14. | um-bar'-na | FMBSS |

| 15. | na-mai-gor'-la | W, FMBSD |

| 16. | ma-gar-ra | MBS, MBD |

| 17. | nī-djal'-lī | S, D |

V

We are now in a position to review Lévi-Strauss’s assertions about the Mara system and, consequently, to judge the validity of his hypothesis about patrilateral systems as a basis for alternation.

I In the Mara system there are four lines; these are named and grouped into two moieties. The fact that ‘the son remains in his father’s división’ does not ‘give the four divisions the appearance of patrilineal lines grouped by pairs into two moieties’ (Lévi-Strauss 1949: 248). The four divisions coincide with the four lines, and it is indifferent in this case whether these divisions are considered as an additional feature or as the same entity, under another aspect, as the four lines. The fact is that what we call lines are special groupings of Mara categories which the Mara themselves actually distinguish by name. In this sense, the named lines of the Mara are no different from those of the Iatmül.

Figure 27 Mara relationship terminology (Warner 1933, cf. Table 10)

2 The Mara system does not differ from the Aranda system in its rules of marriage. In both systems the prescribed category is, contrary to Lévi-Strauss’s assertion, ‘strictly identical’. In both cases this category is genealogically specified as MMBDD, FFZSD, FMBSD, MFZDD.

The alternative marriageable category is that specified as MBD, FZD, as is consistent with a system composed basically of exogamous moieties. In this respect, the Mara do not differ from the Dieri, i.e. when a person of the right category is not available for betrothal, the second choice is a person of the other category of the same genealogical level in the opposite moiety.

3 There is no evidence whatever of a previous ‘patrilateral orientation’ which is now ‘submerged in the apparently bilateral form’ of the alternate marriage among the Mara (cf. Lévi-Strauss 1949: 251). Both the prescribed category and the alternative ‘lawful’ category are strictly bilateral because of the symmetry of the system.

The Laierdila case, studied by Sharp (1935), does not add any relevant clue in support of Lévi-Strauss’s idea of a previous ‘patrilateral orientation’. Among the Laierdila also, the terminology consists of four lines; there are eight sections arranged into two exogamous groups; and the alternative marriages are, as among the Mara, with categories belonging to the opposite major division. The difference from the Mara system is that the Laierdila allow marriage with categories belonging to consecutive genealogical levels, i.e. MBSD and FFZD (also FMBD). Both of these categories belong to the opposite division, and neither of them reflects a ‘patrilateral orientation’ but only the fact that there are two major exogamous divisions.

4 The Mara system should not be considered as ‘an Aranda system which has lost some of its superficial characteristics’, as Lévi-Strauss quite correctly points out, though it must be said that nobody has ever suggested this possibility. But neither should it be regarded as ‘an original and heterogeneous system upon which Aranda features are gradually being imposed’ (1949: 252). Again, Lévi-Strauss maintains that the Mara system should be regarded ‘as a system effectively with four classes and a borrowed Aranda-type terminology’ (1949: 249). But there is no reason to conceive the system in this way either. As for the further suggestion by Lévi-Strauss, the conclusion should be again negative: one could not possibly consider the Mara system ‘as a four-class system with patrilateral marriage, . . . expressed in terms of an Aranda type system’ (1949: 251).

There are three main reasons for rejecting all of Lévi-Strauss’s suggestions:

(i) the Mara system, as we have already seen, has a terminology the features of which are exactly the same as in the Aranda;

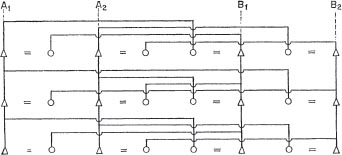

(ii) the distribution of categories in the Mara four divisions has nothing to do with the distribution of categories in a so-called four-class system. The Kariera (a ‘four-class’ system) have a two-line terminology, and positions in consecutive genealogical levels of each line belong to different sections, so that the four sections are grouped into two main divisions coinciding with the two lines. The Mara have instead a four-line terminology; consecutive positions in each line are grouped in the same named division; and the difference between the correspondence of lines, divisions, and grouping of consecutive positions in each line can be seen in Figure 28;

Figure 28 Difference between the distribution of divisions by lines in the Kariera system (.Figure 28a) and the lines of the Mara system (Figure 28b)

Note: A1 A2, B1 B2 correspond to the named divisions

(iii) as we have already seen in (3) above, there is nothing in the Mara system that can be assimilated to ‘patrilateral marriage’, nor is there any indication that this was a prior stage in the evolution of Mara marriage regulations.

VI

The Mara relationship terminology, as a mode of social classification, does not differ from that of the Aranda. Moreover, the four cases examined here, namely, Aranda, Dieri, Iatmül, and Mara, can be classified together by some of the basic principles that they apply, i.e. (1) all of them are lineal, (2) all of them present the features of a closed classification, (3) in all of them the prescribed category can be defined by the relations of alliance of one line with respect to two other lines.

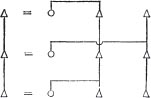

Figure 29 The prescribed category in alternating systems

Figure 29a Matrilines

Figure 29b Patriliness

For each line, the principle involved in the determination of the prescribed category can be represented as follows (see Figure 29). Consecutive positions in one line are related affinally to two different lines. The number of lines – four as in the Aranda, the Dieri, and the Mara, and five as in the Iatmül – derives from the principle of symmetry or asymmetry in force.

The alternation of terms in each line can then be seen as a result of three factors: (i) a lineal classification, (ii) a closed classification, and (iii) a principle according to which a line cannot be affinally related to the same line in two consecutive genealogical positions.

This negative factor (iii) can be seen as a matrilineal principle applied to a terminology composed of patrilines, or as a patrilineal principle applied to a terminology composed of matrilines. Whether such an approach can be regarded as a reversion to the theory of alternation as a consequence of ‘double descent’ depends very much on what is meant by ‘descent’. Formally speaking, the descent lines in the terminologies considered are either patrilines (Aranda, Mara, Iatmül) or matrilines (Dieri), and very clearly so; in other words, the terminologies cannot be coherently organized on the basis of lines of the opposite kind. The social organization of these societies is consistent with these formal traits. Membership in exogamous groups such as sections, subsections, and moieties among the Aranda, the so-called semi-moieties among the Mara, the totemic clans and moieties among the Dieri, and the ngaiva and initiatory groups and moieties among the Iatmül, is determined by the same principle as is expressed in the terminological lines of each of them. Except for the fact that residence is patrilocal among the Dieri, there does not exist in any of the societies considered any ‘bundle of rights’ of comparable significance transmitted in the line opposite to that on which the terminology is based. ‘Double descent’ or ‘implicit matrilineal moieties’, in the case of the Aranda or the Mara, is a complicated way of saying that an individual is not affinally related to the line to which his mother belongs. The same holds for ‘patrilineal moieties’ among the Dieri. This agrees with Dumont’s point, in discussing the validity of Radcliffe-Brown’s explanation of ‘alternation’ by the superposition of patrilineal and matrilineal moieties (either ‘real’, ‘implicit’, ‘latent’, or ‘underlying’), that ‘it would seem that Australians nowhere recognize a double set of moieties’. But, in the light of the examples analysed here, it cannot be agreed that systems of alternating generations are to be explained by ‘intermarriage between sections in preference to hypothetical holistic matrilineal descent’ (Dumont 1966: 249).

The fact is that ‘sections’ are not a necessary institution for this kind of system. They do not exist among the Mara any more than they exist among the Dieri, yet these systems are no different from that of the Aranda. It is true that Dumont, when giving this explanation, is considering the Kariera, the Aranda, and the Murngin, all of which do possess sections. But as sections are not present in all alternating systems, they cannot be accepted as ‘the real agent’ (Dumont 1966: 249) of these systems. On the other hand, if the Kariera and the Aranda are similar because they possess sections, they differ in their forms of social classification. In the Kariera system the alternation is given by the fact that people of consecutive genealogical levels belong to different sections. This fact does not produce in the Kariera system any modification with respect to the line to which each category is affinally related. In this terminology there are only two lines, and people of consecutive genealogical levels do marry in the same line. The sort of alternation involved in the Kariera system is thus different from that which characterizes the Aranda, Mara, Dieri, or Iatmül systems. It could even be said that the sort of alternation in a Kariera system is purely symbolic, i.e. the mode of classification involved with reference to alliances between lines does not differ from that of a two-line symmetric terminology in which consecutive genealogical levels are not distributed among sections. The prescribed category is the same, and there is no alternation of lines to which two consecutive positions are affinally related.

The four cases that we have examined can be defined by a principle such as that represented in Figure 29. Whether patrilineal or matrilineal, symmetric or asymmetric, with sections or without, this mode of articulation is present in all of them. In this respect, it is not possible, either, to agree with the two ‘generalizations’ expressed by Sperber, who, following Dumont, asserts that:

(1) There is no alternation of generations without a partition of the population into classes, according to which the men from one class marry in only one other class.

(2) There is no partition into classes without symmetry according to which the men and women from class A marry in the same class B (Sperber 1968: 185).

First of all, the cases of the Mara, the Dieri, and the Iatmül, which do not have any ‘partition into classes’, refutes generalization (1). The implication derived from (1) and (2), namely: ‘there is no alternation without symmetry’, is refuted by the case of the Iatmül.