In Defence of Art

On Current Tendencies in Film Criticism

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

W. B. YEATS, The Second Coming

I have never felt myself a part of any critical establishment, sub-establishment or anti-establishment; I have tried to be myself, and to go my own way. Yet I always seemed to get on easily enough with my fellows in different camps—despite my intermittent tendency to insult some of them in print. Then I went to Canada for three years, and when I came back, everything had subtly changed, to an extent that I have only gradually begun to measure. Everyone had read books I had never heard of, in disciplines I scarcely knew existed; everyone was talking about semiology, and about “bourgeois ideology”; everyone gradually became revealed as (more or less) a Marxist. I have never felt exactly taken to the heart (or hearts—it has undergone several transplants) of the English critical fraternity, but I have never felt so little welcome, so alien and alienated, or so “vieux jeu,” as I have since my return. If I sound at times like Kevin McCarthy in the later stages of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, the reader’s forgiveness is asked in advance: it does seem to me sometimes as if, every time I turn around, another of my acquaintances has become a “pod.”

“Everyone” is of course a somewhat absurd exaggeration: the Marxist-semiologists (not all of them are necessarily Marxists, and not all are committed to semiology, but the generic title is difficult to avoid) form, after all, quite a small group. They are, however, by far the most active, the most assertive, the most dogmatic, the most impressive and the most organized group currently operating; and the development of British film criticism in the past decades has been largely a matter of small groups overlapping, displacing, superseding one another, each centred on a magazine: the Sequence group, the Movie group, the Monogram group, the Screen group. What is so impressive, and so daunting, about the last is the impression it gives of impregnable organization; the sense of certitude it exudes, as though opposition were superfluous—outmoded, as it were, by definition; the strength it draws from resting upon a formidable body of doctrine, a fully articulated ideological substructure, as well as upon a science with its own elaborated vocabulary and its own extensive bibliography. All must feel intimidated, as they never were by Movie or Monogram; the commonest reactions seem to be to submit humbly, or to try, uneasily, to laugh it all off; neither strikes me as healthy.

The problems of grappling with it all are, however, immense; to do so adequately would require an intimacy with both the ideology and the science that I do not possess. What follows will scarcely worry the exponents and champions of the new criticism, who will not regard it as an effective challenge. I offer, at most, a series of skirmishes, not a major battle; my aim is to voice doubts, questions and anxieties rather than to demolish. I do not believe, however, that I am concerned merely with the peripheral: on the contrary, the tendencies and implications that most worry me are so deeply embedded in the process we are experiencing as seldom to rise to the surface in the form of explicit admission. My attitude to the movement as a whole, and to any of its major components (Marxism, semiology, the recent work of Godard, the investigation of the Hollywood cinema, the deconstruction of Realism), is far from simple. I hope the series of probes that follows—deliberately discontinuous, allowing me opportunities for digression, qualification, approach from different angles—will be found ultimately to have its own unity as the expression of a complex but not incoherent position.

1. Lines of Advance

First, lest the dilettantes of film criticism feel tempted to draw any comfort or support from my work, I want to dissociate myself decisively from those whose attitude to Screen (and I use the magazine here as a convenient short-hand to indicate the whole movement for which, among English-speaking peoples, it has become chief spokesman: much of the initiative is derived from Cahiers du Cinéma) is expressed in facile ridicule. I may join them in finding its language frequently impenetrable, but (while reserving the right to trace a relationship between that language and the aspects I find most sinister) I feel that the problem is as much ours as the writers’: every new discipline creates its own vocabulary and idiom.

Most that is interesting and valuable in current film criticism has developed out of the semiological/structuralist/Marxist school. I don’t see this as proof of the absolute or exclusive “rightness” of that school; simply as yet another demonstration that any concerted movement involving a number of gifted and intelligent people in a living interchange and development of ideas will, whether in art or criticism, inevitably produce good work. The laboriousness of current semiological analysis—I have in mind as example Raymond Bellour’s analysis of twelve shots from The Big Sleep in Théories—Lectures (translated in Screen, Winter 1974/75) whose interest, we are told, lies in their “relative poverty”—should not be surprising, nor its apparent mistaking of means for ends: it is as if an English teacher suddenly discovered clause analysis and was so excited by it that it seemed, for a time, the only way to talk about a Shakespeare sonnet. We urgently need a syntax of film which we can draw on freely—as an occasional recourse to clause analysis may miraculously clarify a passage in Shakespeare—and semiology (when the excitement has settled down) may turn out to have supplied one.

A number of specific (and interrelated) lines of enquiry in current criticism seem to me particularly important and rewarding:

a. The whole investigation into the ideological substructure of art, which has already provided its revelations. Of course we should be aware of the implicit ideology supporting and structuring a given work: nothing should be merely taken for granted or left unquestioned.

b. The investigation into the narrative conventions of the American classical cinema and their ideological determination, the reasons why certain plot-structures recur insistently while others appear freakish or inadmissible.

c. The ways in which ideological structure may be cracked or subverted in individual cases, and by what means (the celebrated Cahiers text on Young Mr. Lincoln can stand as locus classicus).

d. The enquiry into Realism, and the exposure of the artifice that underlies it, the strategies and conventions through which “Realism” seeks to impose itself as “reality.”

e. The attempts at offering detailed “readings” of particular films that, while acknowledging the evidence of directorial authorship, go beyond the tracing of personal themes to reveal the multiple determinants that may contribute to the finished product.

All of these developments have had their effect (as a stimulus, and not merely a negative one) on my own recent work. Together, underpinned as they are by Marxist doctrine and the discipline of semiology, they constitute so formidable a critical front that the problem is how to assimilate them without getting assimilated by them (a fate that has, I’m afraid, overtaken a lot of people recently); how to learn from them without losing one’s personal voice and individual integrity. I do not, myself, find them necessarily incompatible with the view of art and its function that I have previously expressed; indeed, I would assert that their validity largely depends on their compatibility. Without some such sanction—should they come to be generally accepted, that is, as ends in themselves—there is a danger of their becoming destructive of art itself.

2. Against “Impressionistic” Criticism

Semiology is commonly proposed as the answer to “impressionistic” criticism. No one who has tried to write on film with any precision will doubt for a moment the need for analytical tools that can help guard against vagueness and lapses of memory and render the sort of useless disordered casual jottings that frequently pass for perceptive criticism impossible.

One could illustrate what is meant by “impressionism” in this context, and so give force to these assertions, from a superabundance of sources (including much of my own past work). I choose Manny Farber’s Negative Space partly because the book is (I believe) highly regarded in some quarters, partly because of its general air of confidence and the apparent precision of many of Farber’s observations. For striking examples one need look no further than the introduction.

Here is Farber on Touch of Evil: “A deaf-mute grocery clerk squints in the foreground, while Charlton Heston, on the phone, embarrassed over his wife’s eroticism from a motel bed, tries to suggest nonchalance to the store owner.” One wonders for a moment whether Farber has seen a print containing a scene generally cut; but his account bears just enough resemblance to a familiar scene to make this improbable. Farber seems to think there are two people in the little general store with Heston, a deaf-mute clerk and the store owner; there is in fact only one, and Heston would have difficulty in suggesting “nonchalance” to her (unless with his voice): she is blind, not deaf-mute. Farber continues, again with an air of confident precision: “A five-minute street panorama develops logically behind the credits, without one cut, just to arrive at a spectacular reverse zoom away from a bombed Cadillac.” Pedantic, perhaps, to point out that the opening shot lasts three minutes twenty-five seconds and that “panorama” is somewhat misleading as it suggests a panning shot; less pedantic to point out that, just after the explosion is heard off-screen, Welles cuts to a shot of the blazing car (it would have been difficult to do otherwise without actually blowing up two actors) on which he then zooms in.

A few pages later we find Farber summing up the “resonance” of Weekend thus: “These hopped-up nuts wandering in an Everglades, drumming along the Mohawk, something about Light in August, a funny section where Anne Wiazemsky is just sitting in grass, thumb in mouth, reading a book.” The term “impressionistic” has particular felicity applied to writing like this: the sentence evokes a generalized impression of Godard movies with which the casual reader (and viewer) is assumed to be satisfied. There were funny scenes in Weekend (though whether Farber means funny-peculiar or funny ha-ha I’m not sure); there was a shot in which Anne Wiazemsky sat by a lake reading a book, though it is difficult to see what Farber found funny about it. She was, in fact, smoking a cigarette, but perhaps she was also sucking her thumb in another movie, or perhaps that was Anna Karenina somewhere else, or perhaps Farber (having discussed The Big Sleep a few pages earlier) was confusing her with Carmen Sternwood; and Godard said somewhere that Made in USA was a remake of The Big Sleep, so it all sort of links up, so what the hell? The whole chapter, with its extraordinary associational processes, comes very close at times to stream-of-consciousness, and is worth looking up as an example of what you can get away with, with a bit of swagger. Such “impressionism” says as much about Farber’s assumptions about his readers as it does about his own perceptions and his way of experiencing films. It is assumed that they will not know the films very well either, but will not feel this as much of a handicap in attending to discussions of them so vague as to be unchallengeable.

Faced with writing like Farber’s, one’s sympathy for semiology certainly increases. The trouble is that the claims made for it as the alternative to this kind of thing rest on a use of the word “impressionistic” to cover pretty well everything from Sight and Sound’s “guide to current releases” to V. F. Perkins’s Film as Film: if it is not semiological then it is “impressionistic.” The term becomes a means of vilifying everything indiscriminately by blurring all distinctions. Peter Harcourt’s studies of six European directors, in his book of that name, are (though also prone to descriptive errors) in a different class from Farber’s “impressions,” offering the precise and cogent articulation of responses to central features of the directors’ work; the analyses in Perkins’s book gain their validity from their meticulous precision; the term “impressionistic” cannot possibly do justice to either. Both books demonstrate that it is possible to present precisely defined and arguable propositions about films and still write what the general reader can recognize as the English language. One can imagine readers of weekly “journalist” criticism learning to master Harcourt and Perkins (and learning, as a corollary, to reject most of the journalism); they could not master a great proportion of recent issues of Screen without substantially re-educating themselves. This may be—as most Screen editors and writers would claim—because Harcourt and Perkins both write “within the prevailing ideology.” The implication—that one cannot make oneself generally intelligible without thereby becoming “bourgeois”—is an alarming one, and relates interestingly to Godard’s present quandary as a film-maker. I am less pessimistic (perhaps because I am a bourgeois myself): it seems to me that semiologically-orientated criticism may in time, after its necessary period of intensive consolidation, learn to move (to pursue the Godardian parallel) from a Vent d’Est phase to a Tout Va Bien phase. Meanwhile, my quarrel is less with what it is actually doing than with its arrogant self-assertion: the common assumption that any alternative is now discredited and made obsolete by its example.

3. Mizoguchi Replies to George Steiner

Two basic objections to the view of the function of art put forward in my opening essay need to be confronted. They can be summed up crudely as (a) it doesn’t work and (b) it isn’t valid. The former has been put with considerable show of efficacy by George Steiner, in Language and Silence (he is talking about literature but the point applies, I think, to the arts generally):

The simple yet appalling fact is that we have very little solid evidence that literary studies do very much to enrich or stabilize moral perception, that they humanize. We have little proof that a tradition of literary studies in fact makes a man more humane. What is worse—a certain body of evidence points the other way. When barbarism came to twentieth-century Europe, the arts faculties in more than one university offered very little moral resistance, and this is not a trivial or local accident. In a disturbing number of cases the literary imagination gave servile or ecstatic welcome to political bestiality. That bestiality was at times enforced and refined by individuals educated in the culture of traditional humanism. (p. 83, Pelican edition)

It is common knowledge (or common myth, which is often truer than knowledge) that concentration camp commandants would come home after work in the evenings and play Schubert exquisitely on the piano. But this seems to me an incitement, not to despair or to the surrender of my position, but to greater awareness, more rigorous definition, more militant commitment. Let us admit at once that art and the study of art offer no instant solution to human problems, no instant exorcism of human evil, no instant strengthening of human goodness; that it is naive in the extreme to argue that contact with the arts in itself refines, ennobles or humanizes. The simplest answer to the objection is that the commandants probably had not studied under Dr. Leavis. In case that sounds frivolous to some and downright silly to others (I should not, certainly, wish it to be understood too literally!), let me expand. We all know that an alleged interest in art can be cultivated in many forms, at many different levels of respectability: as a sort of snobbish social or intellectual one-upmanship; as the development of “correct” taste or connoisseurship; as the accumulation of knowledge—what is commonly meant by “scholarship.” Taken together, these forms can be claimed to represent the dominant tradition of our culture, the “establishment” view of art from the university milieu that has always found Leavis such an embarrassment, down to the Sunday colour supplements. What all these forms of interest have in common is the treatment of art as something out there, external to the individual, to the values by which he lives (as opposed to the values to which he pays lip service), the way he thinks and feels from moment to moment in his daily life, in his social activities, his work, his personal relationships. “Appreciation” (such as is often taught in schools) is a term that comes to mind: one learns to “appreciate”—at a certain distance. One learns to say the right things and even, up to a point, mean them—one can even teach oneself to feel the right feelings. The distinction between “appreciation” and critical evaluation is crucial. Art remains a leisure-time activity, something one comes home to whether from the concentration camp, the factory, the office, the university lecture theatre. When I was at Cambridge reading English this was an attitude that all the lectures tended to encourage and endorse, except those of Leavis and A. P. Rossiter; and an attitude gratefully accepted by the majority of students.

The most sophisticated and insidious form of this externalizing of art is to aestheticize it—to purge it of all its moral, social and ideological perplexities. Leni Riefenstahl offers a frightening example, which relates very closely to George Steiner’s objections and illustrates simultaneously the sort of aesthetic position to which Leavis is so strongly and committedly opposed. According to her present testimony, when she made Triumph of the Will she was interested solely in her “art,” and was quite ignorant of the socio-political implications of what she was filming: she was the “innocent” but dedicated artist, feeling a responsibility to nothing but her “art” (equated roughly with abstract aesthetic beauty). We may believe her or not: all that is necessary for the present argument is to establish the terrible possibility of the unaware artist, placing himself unwittingly at the service of some enormity, and the unaware “appreciator” who passively reflects his attitude to art.

The answer to George Steiner (and to Leni Riefenstahl) is also implicitly given in Sansho Dayu (itself a supremely great work of art, which is part of the point). Sansho keeps his slaves in abject misery, branding them with red-hot irons if they try to escape. His estate is not altogether unlike a concentration camp: the film, made less than a decade after World War II, opens with an ironic foreword locating the legend it recounts in an age “before man awakened from barbarism.” In one scene, Sansho entertains an emissary from the Minister of Justice (on whose behalf he runs the estate) with a display of high culture in the form of traditional song and dance. The performance is largely ignored: Sansho is intent on watching its effect on the emissary, the emissary is more interested in the chest of jewels with which he has been presented, Taro (Sansho’s son) turns aside in disgust. The music continues through the following scene in which Taro talks to the two slave-children (the film’s central figures) prior to his departure, outraged by his father’s brutish insensitivity to the suffering around him.

The comment on a particular use (or abuse) of art is plain enough. But Mizoguchi’s answer to Steiner is not that one scene, but the whole film, which, though made within one of the world’s largest commercial film industries, is itself a work of high art. Its leading theme is the necessity for preserving one’s humanity, one’s capacity for human feeling and human commitment, even in the most brutalizing and seemingly hopeless circumstances. The film, rich in disasters, reveals as the only absolute disaster the loss of that humanity, as typified, temporarily, in the protagonist Zushio’s submission to a “realistic” attitude to his situation—his acceptance of the need to brutalize himself and adjust to the condition of the earthly hell in which the slaves exist. That theme, and the values that make its expression valid and convincing, are realized in the art of the film, through its structure and its style, the constant tension and balance set up between involvement and contemplation. Thus the film embodies the concept of humanity that it upholds, implying an attitude to art and a sense of its function very different from Sansho’s.

4. Schubert Replies to Colin McArthur

The second objection—that my conception of the function of art is invalid—takes us nearer the heart of the current film critical debate. The clearest brief statement of it I have found is in a review of Peter Harcourt’s Six European Directors by Colin McArthur, which appeared in Tribune (5.7.74). It is significant (and symptomatic), I think, that, while granting the book a certain intelligence, McArthur nowhere attempts to grapple with its arguments: he simply rejects its position on ideological grounds, the intelligence being, apparently, neither here nor there. That quality is no longer a relevant concern is an assumption one encounters in many forms nowadays: at its base seems to be a sense that the notion of “quality” is itself “bourgeois.” After placing Harcourt’s book within a “liberal/bourgeois/romantic view of the world utterly at odds with the materialist view,” Mr. McArthur writes:

Mr. Harcourt’s romantic commitment to the personal response of the critic is paralleled by his ultimate commitment to the notion of personal artistry . . . the materialist critic would offer an alternative model of the critical activity. Naturally, he would pay scant heed to his own (or anyone else’s) personal response to a film since, from the materialist perspective, “personal” responses are not personal at all but are culturally and class-determined.

The surprising thing about that last remark is the triumphant way McArthur brings it out, playing it like a trump card, as if he had just discovered it. But has anyone ever doubted that our responses are conditioned by our upbringing, background, environment, by a vast intricate network of influences consciously or unconsciously assimilated? Could it conceivably be otherwise? And how does this suddenly make them not personal? If I sit next to someone from roughly the same cultural background as myself watching Tokyo Story, Rio Bravo or Diamonds Are Forever, am I to assume that our responses are identical—that there is no personal “I” and “he” who might be relating to the film in radically different ways? Or is the assumption (which I find profoundly sinister) rather that the personal “I” and “he” no longer matter, are irrelevant to what life and art are really about and had better be discounted or obliterated?

There are a number of objections to be made to McArthur’s objection, though the critical (and ideological) position it implies is today very common among the “intellectuals” of film criticism. First, his position seems to depend on an extremely simplified and crude notion of the term “response”: he appears to conceive personal response as a subjective and mindless emotional gush, not as the delicate and complex intercourse between emotion and intellect that I have always taken it to be. Second, McArthur’s position frighteningly implies, logically, a rejection of feeling itself. For if our responses to art are to be dismissed as “culturally and class-determined,” then surely our responses to other people, and to situations in life, must be so too? The only solution would be a willed inhibition of all emotion as we ruthlessly deconstruct ourselves, our friends and our relationships.

I am reminded of a brief passage (two shots) in Godard’s Vladimir and Rosa which I also find somewhat chilling. We are shown Juliet Berto as activist and militant (a close shot of her in a tense, defiant pose), then a shot typifying the way she lives. Meanwhile, the voice-over commentary informs us sternly that she has not yet found the way to relate the two images—the public, activist life, the private, daily life. One might expect from this description that the second shot would show her sitting before the fire with her bourgeois parents darning the family stockings. Not at all: we see her relaxing with some fellow students in what looks like a communal home. Now what, one may ask, does Godard want the poor girl to do? Can she not sit and chat with her friends? Must life be one long conscious (and self-conscious) deconstruction? There is, of course, a real quandary here, to which one cannot but be sympathetic: to revolutionize the whole of society must be to revolutionize every aspect of one’s own life. Yet the damage this must inevitably do to the human personality scarcely bears thinking of. Yeats’s lines on fanatics come aptly to mind—they haunt me continually when I watch recent Godard:

Hearts with one purpose alone

Through winter and summer seem

Enchanted to a stone

To trouble the living stream.

I have been told, on very good authority, that I am an “anti-intellectual,” because my work consistently implies a refusal to separate my emotional life from my intellectual life. Such a separation, in my view, can only be, ultimately, to the detriment and impoverishment of both.

There is a third, related objection to the position implicit in McArthur’s review (and, I believe, in the pages of Screen): it appears to lack any sense of the function of art. The review continues: “He (the materialist critic) would be concerned with the cinema as a social process and with producing knowledge about that process, which implies knowing equally about socio-economic structures and aesthetic structures and posing relationships between them.”

Let me say at once that the posing of relationships between socio-economic structures and aesthetic structures seems to me an admirable and potentially very rewarding critical pursuit. Also, there could be no possible objection to anyone’s examining the cinema as a social process. This cannot, however, logically be considered a substitute for the traditional relationship between art and criticism. The fact remains that artists don’t create works of art in order to provide sociologists with data. Works of art, like everything else, become potential sociological data, and it is perfectly valid to explore their significance from that point of view. But without a sense of the creative process on the one hand and the experience of art on the other—in other words, of personal artistry and personal response—the critic cannot talk about art as art: he is denying it its original, central and defining function. Ultimately, an exclusive approach that in effect reduces the arts to a heap of data can only be destructive of art.

A work of art affects our emotions, fascinates our mind, becomes a part of our consciousness and of our unconscious—a part of our selves. Repeatedly, through life, I have found myself living with a particular work, or the works of a particular artist, over a period of time, with the greatest intensity and growing intimacy: at present it’s Schubert’s Winterreise, which I have recently discovered. It’s not just that I want repeatedly to listen to it—it’s part of my breakfast every morning, it runs through my dreams at night, it’s with me while I do the cooking or fiddle about the garden. Gradually, I feel it becoming a part of me, and the obsession begins to diminish. From there on, I need to experience it less, because it’s absorbed into my life, it’s in my bloodstream.

This kind of assimilation—of which I’ve given an extreme example, for we are not capable of “living” every work of art we encounter at such a pitch of intensity—seems to me fundamental to any understanding of what art is and what art is for. The process of absorption I have described is clearly not only—perhaps not primarily—a process of conscious understanding and of intellectual exploration: it is a process engaging the emotions and instincts as much as the mind. It becomes impossible without some degree of trust: trust of our own response, trust of the artist and the work. It is easy to see that, from the Marxist viewpoint, this trust is itself an aspect of bourgeois ideology, or, rather, the means whereby that ideology can perpetuate itself. Yet if we deny it, it seems to me that we deny our own humanity and deny art (as Godard, indeed, has done or at least tried to do).

At the same time, such trust has to be counterbalanced by its opposite, by the achievement of critical distance, by questions of choice and value. The process by which we decide what works of art we will live with, what we shall allow to affect, influence and modify our sensibilities, is obviously a complex one. When the decision becomes exclusively one of the intellect and the will—when it is determined, that is, by a rigidly held body of dogma allegiance to which demands that our spontaneous responses be suppressed—then we do both ourselves and art an injury.

5. Totalitarian Tendencies in the Cinema

Within the revolution, anything;

against the revolution, nothing.

FIDEL CASTRO, Words to the Intellectuals

Let us juxtapose, for a moment, Battleship Potemkin, Triumph of the Will and Vent d’Est: three films quite distinct from each other in period, cultural background, political ideology, form and style. They have one thing in common: none of them permits the spectator, within the work, an alternative view to the one promulgated by the film-maker. Eisenstein (for better or for worse—the point is arguable) does not allow us to think, “The ship’s officers are human beings too”; Riefenstahl does not let us think, “Hitler may be a real bastard.” The case of Vent d’Est is slightly more complicated (much has been made, notably by Peter Wollen in his article “Counter Cinema” in Afterimage No.4, of its formal “aperture”). But, while his film expresses some uncertainty as to the most effective methods for revolutionaries (or revolutionary film-makers) to adopt, Godard nowhere allows us to question the desirability of revolution.

Against these films set Pontecorvo’s Battle of Algiers (a film the “politicized” tend to lump indiscriminately with the works of Costa-Garvas—another manifestation of their indifference to quality). The main inclination of the film’s sympathies is abundantly clear. Yet Pontecorvo is able to present the commander of the paratroopers as an intelligent human being capable of presenting a rational defence of his position; the film’s argument allows that, while that position is regarded as “wrong,” it has something to be said for it, it can be rationally defended. Pontecorvo’s film also confronts the issue of the morality of placing bombs in public places where “innocent” people will be killed and injured, and here it offers opportunities for direct comparison with Vent d’Est. Battle of Algiers presents the argument that the terrorist acts were necessary, though terrible: we are encouraged to respond to the terribleness, to ponder the consequences seriously. Godard’s film, after offering some instruction in the manufacture of bombs, simply tells us (in a voice-over commentary accompanying some typically “anonymous” images) that any objections we may raise to the placing of bombs in supermarkets are examples of liberal humanitarianism which is one of the disguises or subterfuges of capitalist ideology: any qualms we may feel about the indiscriminate massacre of shoppers are brutally squashed by the method of making us feel ashamed of them. The issues Pontecorvo’s film raises could be discussed from different positions by people of different political persuasions, drawing on and developing arguments implicit within it; the propositions offered by Vent d’Est could only be discussed by committed revolutionaries. To discuss the film’s overall position one would have to move outside it, and in effect argue against it: there is no foothold within it for anyone less than totally committed to its premise. It is one of the most extreme examples of “elitist” art in my experience. It seems fair to describe Battle of Algiers as a democratic film, and “open”; the other three as, in their different ways, totalitarian, and “closed.”

A more flagrant example of cinematic totalitarianism is offered by Pravda, the Godard-Gorin political documentary on Czechoslovakia. The voices of the two commentators (who call themselves “Vladimir” and “Rosa”) warn us near the beginning that if we do not understand Czech we had better learn quickly. Subsequently, we listen at length to an (unsubtitled) Czech factory worker; we are then told that if we do not understand it does not matter after all—the worker talks like Henry Ford. The same tactics are repeated later (slightly varied) with farm workers. So much for the presentation of evidence. And so much for respect for the human individual, be it the workers (who are denied their own viewpoints) or the viewers (who are denied the right to judge for themselves). All particularities are annihilated in favour of the crudest ideological generalization. One might be tempted to call such tactics “Fascist” if they were not merely silly. They raise, acutely, the recurrent problem in Godard, the problem of tone, or degree of seriousness. One feels at times that he and his associates are playing at revolution, very dangerously, like a gang of kids left in a room with matches and explosives.

One rider must be added here: the preceding argument does not necessarily mean that I value Battle of Algiers above Vent d’Est: simply that I find it ideologically more acceptable. Such conscious ideological concerns must enter into that bewilderingly complex process we call evaluation (and unconscious ones cannot, by definition, be kept out); but they represent only one strand among many. It is a process, in any case, that should never be supposed to have reached the stage of the “definitive” towards which it must perpetually strive.

6. Totalitarian Tendencies in Criticism

The attitude to democratic critical debate revealed generally in Screen significantly parallels the attitude of Pravda and Vent d’Est. (“Within the revolution, anything; against the revolution, nothing.”) Before taking up the issue in general terms, I want to examine one or two local details. I do not intend that they be taken as representative of Screen as a whole, but I feel that, in their relatively trivial way, they are symptomatic. I offer two examples from an editorial, two from an article.

In the autumn of 1972 the editor of Screen undertook the task of introducing two critical articles, the Cahiers text on Young Mr. Lincoln, and John Smith’s article on certain of Hitchcock’s British films. This is how he dealt with an essay he (or the editorial board) had selected for publication: “John Smith relates to an older and I think incorrect aesthetic position but one nevertheless in the mainstream of British film criticism. . . . Both formalism . . . and semiology have revealed the essential realist and hence ideological impulse involved in this species of romantic aesthetics and at the same time, in work on the sign systems of art, have theoretically demonstrated the untenability of that aesthetics.” In other words, if you can’t speak Czech it doesn’t matter. It happens from time to time that an editor finds it necessary to dissociate himself from positions he has none the less found interesting enough to represent. Bazin did it in Cahiers in a way I find exemplary, in that it constituted a challenge to his own “jeunes Turcs” to consolidate and define their position more convincingly. He did not, however, emasculate articles in advance, warning his readers, in effect, not to take them seriously.

There is a very curious moment earlier in the same editorial—the writer here being involved in a parallel manoeuvre to justify the Cahiers text, in the form of an advance explanation:

The ideology of Ford’s film which the Cahiers writers describe variously as “the Apology of the Word” (natural law and the truth of nature inscribed in Blackstone and in the Farmers’ Almanac), the valorisation of the complex Law of Nature/Woman, the repression of violence by the Law, and the suppression of history by the myth, are disrupted by the film’s signifiers. For example the violence repressed by the Law and the Word is reinstated by the violence of that repression (Lincoln’s castrating look, the murder, the lynching).

The writer’s somewhat feverish haste is suggested by the faulty syntax (“The ideology . . . are . . .”); his example (the only one offered) of “disruption by the film’s signifiers” comes perilously near the meaningless. “The murder” and “the lynching” cannot possibly be put forward as examples of the violence with which violence in the film is repressed: the lynching is the violence that is repressed; the murder (which Lincoln does not witness) by no stretch of the imagination represents the repression of violence “by the Law and the Word.” One is left, then, with “Lincoln’s castrating look”; whether “violence” (as opposed to some such term as “moral force”) is really the right word seems open to argument: both here and in the Cahiers article itself, the equation of moral force with physical violence is somewhat dubious. The lapse in the editorial, however, strikes me as the kind of sleight-of-hand (no doubt unconscious) that goes with a general sense of the end justifying the means: as long as the Cahiers article and its aesthetic position are validated it does not much matter how.

My second pair of examples comes from an article Politics and Production by Christopher Williams, published in the issue of Screen for Winter 1971/72. In the first paragraph, after attacking “the diachronic version of Film History,” Williams tells us that “it took history itself, in the shape of the French revolution of May 1968, to force a necessary re-evaluation of the whole concept of political cinema: a re-evaluation that is only just beginning.” He then proceeds to offer us a remarkable piece of film history of his own. I must quote at some length, or I risk being charged with misrepresentation:

In the aftermath of the revolution, Cahiers du Cinéma began to re-publish a wide selection of original Russian material; Cinéthique attempted a meditative praxis in the whole area of political cinema. These moves had their echoes in other cultures. At the same time, about 80% (at a frivolous estimate) of young film-makers became “revolutionaries” of one sort or another. This ferment was so disparate and various that it can’t possibly qualify for description as a “movement,” running as it does the whole gamut from Warholian voyeurism through re-vamped social-concern “realism” to agitational propaganda and sheer abstraction.

The sense is not, perhaps, free of syntactical ambiguity (often an unconscious method for performing sleight-of-hand, asserting what one wishes to assert but does not really believe): it is not entirely clear whether the fact that “about 80% (at a frivolous estimate) of young film-makers became ‘revolutionaries’” is meant as an example of the “echoes” of “these moves” “in other cultures” (if it is not, then the examples are left to our imagination). What is unambiguous is that this happened “at the same time,” which can only mean “in the aftermath of the revolution.” In other words, the American underground (including, explicitly, Warhol) and Cinéma-Vérité (including, implicitly, Rouch and Leacock—Williams goes on to talk about “true-confession, talking straight into camera documentary”) happened after the events of May 1968 and perhaps developed directly or indirectly out of them. Either the piece is just very clumsy or we hover here on the verge of Orwellian “doublethink.”

As the second example from Williams’s article concerns myself, I shall be accused of personal animus; I am certainly ready to confess to irritation. It seems to me, however, a good example of a certain way of dealing with any critical opposition. Williams is discussing Weekend. He remarks: “The film is built around the question of culture, which is what allowed Robin Wood to claim Godard as a belated, tragically-despairing adherent to Leavis and the Great Tradition (New Left Review 39).” Whether “built around the question of culture” is a satisfactory description of Weekend I shall not argue here; whether my article in New Left Review can be fairly described as “claiming Godard as a belated, tragically-despairing adherent to Leavis and the Great Tradition” is best left to readers to decide. However, the fact that Weekend “is built around the question of culture” could not possibly have allowed me to claim Godard as that or anything else in an article written three years before Weekend came out.

As Williams must have known, I wrote my article at about the time of Masculin-Féminin; as he might have deduced from its total lack of reference to that film, I had not been able to see it when I wrote. The article discusses Godard, then, up to and including Pierrot le Fou, but that does not prevent Williams from presenting it to his readers as if it dealt with Weekend. He must also have been aware, I think, that I wrote a much later article specifically about Weekend (first published in Movie, reprinted, slightly cut, in The Films of Jean-Luc Godard) which drastically qualifies the position represented by the earlier piece; bur he sees no reason to refer to this or to acknowledge its existence. It raises questions about Godard that I think still have not been satisfactorily answered, by Williams or anyone else.

It is fair to mention that the editorship of Screen has changed since these examples appeared, and to repeat that they are not adduced here to discredit that magazine as a whole. Nor, of course, are such tactics by any means restricted to the new critical school. I feel, however, that wherever they appear they should be exposed, and the exposure put on record.

Such minute particularities as those I have just examined, however, are mere gnat-bites in the context of the general attack on traditional aesthetics of which Screen has placed itself in the front line. The attack is characterized by the emergence of a whole new vocabulary of “dirty words”—terms which scarcely need to be defined or examined, but can be relied upon, apparently, to elicit an instant stock response from readers. My own readers can test their positions, perhaps, by asking themselves at what point in the following list they begin to feel surprise that the words should be automatically accepted as terms of abuse: bourgeois ideology, liberal, humanist, élitist, Romantic aesthetics, genius, personal artistry, expressivity, creativity. Again, my aim here is not to attack the positive achievements of Screen and the movement it represents, but to raise questions about what is being recklessly swept away and about the implications—for art, for society, for life—of its hypothetical annihilation. My own reaction to these terms is not simple, as I hope the following annotations will suggest.

“BOURGEOIS IDEOLOGY”

For most of us, the term “bourgeois” evokes suburban streets, privet hedges, a narrow moral code, values based on material possession: none of us wants to be thought “bourgeois.” In Marxist criticism, the term inevitably retains these overtones but, by a process of insidious synecdoche, comes to cover a great deal more. Hence its usefulness as a means of effecting recoil over a remarkably wide front. The position of Vent d’Est, for example, comes to appear impregnable. As the term “bourgeois ideology” can be made virtually all-inclusive, covering everything outside Marxist-Maoist doctrine, any objections to the film can be easily “exposed” as its product or its means of selfdefence. The instincts (except the instinct to destructive action) and the emotions (except that of anger) appear to be a part of “bourgeois ideology.” Impulses of love, generosity and tolerance, all readiness to listen to other points of view, everything we have learnt to call, in the finest sense, “human,” all these are aspects of “bourgeois ideology” and its means of perpetuating itself. I do not think we should allow ourselves to be intimidated by this; whenever we encounter the term “bourgeois ideology” in art or criticism it is necessary to determine carefully exactly what it indicates. To off-set the emotive overtones, one might mentally substitute the word “traditional” for “bourgeois.”

“ÉLITIST”

Another word with (in any democratic tradition) emotive overtones that tend to get in the way of what it is actually being made to stand for: it implies snobbery and exclusivity. When confronted with generalized denunciations of the “élitist” view of art, one must begin by asking for a definition of the “élite” in question—what constitutes it, what are the conditions for membership? The answer appears to be “education”: “élitist” art is art you have to learn to appreciate. But the emphasis, surely, must always be on self-education, or, at the very least, on active cooperation between pupil and teacher. No merely passive (let alone hostile) pupil can be made to learn to understand and evaluate works of art. Our “élite,” then, consists of people who either spontaneously want, or deliberately choose to want, to educate themselves. (I am not, of course, talking about those who “cultivate” the arts as some kind of social performance, for cocktail party repartee; I presume the argument is not about them.) It is a closed “élite” only in so far as social (“bourgeois”) pressures encourage philistinism: it is not a club with exclusive conditions of membership. I have spent fifteen years educating myself to respond to and feel at home with the Schönberg quartets, a process at first painfully frustrating, ultimately deeply rewarding. I can now “hear” the third quartet (reputedly the most difficult) almost as naturally as I “hear” the Beethoven third symphony. This places me among a very small minority, but I am not aware of any self-congratulatory feelings of superiority. I am not particularly musical, have had no training and quite fail to grasp the technical intricacies of twelve-tone composition; the experience I get from Schönberg seems to me to be open to anyone who wants it. If I feel no pride because I enjoy allegedly “élitist” art, I also feel no guilt.

It does seem to me, however, that the development of any full response to significant art demands effort, discipline and patience. There are great works of art—plenty of them—which have been enjoyed readily by the general public, but a condition of this enjoyment seems to be that they are not perceived as art. One is glad that My Darling Clementine and Rio Bravo were commercial successes, but do not let us kid ourselves—the audiences who enjoyed them made no significant distinction between them and Gunfight at the OK Corral and High Noon (unless, in the case of the last, they felt they were seeing something more serious and important, with a message). The (Marxist) editors of Cahiers du Cinéma have demonstrated very convincingly that Young Mr. Lincoln is every bit as “difficult” a film as Persona or Pierrot le Fou. If the term “élitist” is defined as “anything that cannot be fully appreciated by anyone, irrespective of background, training and education,” then all art is élitist. As soon as one allows for the desirability of discrimination, then élitism creeps in. What, for that matter, could be more élitist than Godard’s politicized movies on the one hand and semiological discourse on the other? Of the former, Christopher Williams writes (in the Screen article cited earlier): “The (Dziga Vertov) group itself stresses that the films are not intended for large audiences, but for small groups conscious of ideological questions.” You cannot get more élitist than that.

The paradox that it is those very critics who talk contemptuously about “élitist” art and “élitist” positions who also champion the most élitist of all art, can be explained but not very satisfactorily resolved. Avant-garde art (any avant-garde art, one infers from the remarkable extra chapter Peter Wollen added for the second edition of Signs and Meaning in the Cinema) is valuable because it is “progressive”: the work of Godard/Gorin is of course the centre of attraction, but even when the art is not specifically revolutionary in the political sense, its tendency is to undermine and destroy “bourgeois” forms and “bourgeois” assumptions. The avant-garde, in other words, is admirable only in the bourgeois context, as a means to an end: when the revolution comes and a Marxist society establishes itself, it will automatically become redundant. Vent d’Est, it is worth pointing out, although it was very difficult to make within the bourgeois-capitalist context, would be impossible to make outside it: its method, style, peculiar qualities, are all directly dependent on the difficulties. So what sort of art will be able to exist in our coming Marxist utopia?—what is the alternative to the “élitist” art that is being discredited? I find myself unable to supply any answer, but do not wish to imply that there necessarily is not one (I may be too much determined by and enclosed in traditional ideology to be capable of imagining it). It cannot, obviously, be anything that suggests the traditional (“bourgeois”) aesthetic, which will be anathema, and it cannot be anything avant-garde, which will be redundant: the problem with all utopias is that once you have got there, there is nothing to be “progressive” about any more.

In the same light, I think the interest of Marxist critics in traditional art needs to be examined, and fundamental questions asked. The most interesting and stimulating Marxist criticism is clearly that in which the impulse is not to denounce and reject but to salvage. Lurking in the background of the Cahiers text on Young Mr. Lincoln—and necessarily suppressed, but implicit in the article’s own gaps and dislocations—one senses the quandary of critics who grew up loving Ford’s movies, became converted to Marxism after the events of May 1968, and were faced with the task of re-structuring their own past allegiances. (It is striking that the change in ideology has not been accompanied by any significant change in the works and directors admired: the pantheon is the same, but the gods have to be reinterpreted.) The solution of the Cahiers editors is highly intelligent and sophisticated. The film is examined, and implicitly admired, for precisely those features which would appear flaws or failures of realization from a traditional viewpoint: “gaps,” “dislocations,” inner contradictions that disrupt and subvert the film’s ostensible (conscious) purposes, and that finally present Lincoln as a “monster.” I am not at all sure what is left of Young Mr. Lincoln as a work of art after the Cahiers team have done with it; nor is it clear to me that they are sure.

This has taken us some distance from my initial defence of the “élitist” position (which is partly a defence of it against the term “élitist”), but I hope it is still within sight. Before passing on, let me return to it with an obvious, but I hope provocative, question: can anyone capable of genuinely appreciating and assimilating Mozart and Mizoguchi possibly say that he is not, in that respect, immeasurably better off than someone whose cultural horizon is limited to bingo and The Black and White Minstrel Show? The assimilation will not necessarily make him a better person (a common, and obviously fallacious, assumption), but it will open to him possibilities that are closed to his less fortunate fellow humans. If that is what is meant by an “élite,” then I for one shall not willingly sacrifice my membership of it in the name of some perverse and destructive egalitarianism: to put it succinctly, nothing is ever going to come between me and The Magic Flute. It is not, however, an élite from which I would wish anyone to feel excluded: on the contrary, I would like to share my advantages with as many others as possible. That is why I am a teacher.

“ROMANTIC AESTHETICS,” “GENIUS,” “CREATIVITY”

What is actually under attack here turns out always, on inspection, to be some absurd parody-concept that no one today could possibly wish to defend, and which would have looked excessive even at the height of the Romantic movement: the notion that works of art are produced by some process of immaculate conception out of the creativity of an isolated individual genius. But the opposite notion, that denies the concept of personal creativity and individual genius any validity whatever, is no less absurd: do these critics really suppose that Ford’s or Hawks’s films would somehow have come into being by accident if Ford and Hawks had never existed?—or that some readily interchangeable substitute would have been “produced” (“productivity” being, apparently, the alternative to “creativity”)? There is no substitute for an individual work of art, just as there is no substitute, no possible replacement, for an individual human being.

Fra Filippo Lippi’s beautiful “Annunciation,” that hangs in London’s National Gallery, reproduces emblematically a traditional Christian myth, and in doing so draws on an intricate system of aesthetic and iconographical codes and conventions that determine not only the placing and treatment of the figures but govern every detail of the painting down to the execution of the smallest leaf. Yet I see no way of accounting for the totality of the picture’s effect but in terms of the individual sensibility and skill (the latter inseparable from the former, as its means of expression) of a particular painter. The painting is structured on an exquisite system of balances and contrasts. The heads of the two female figures, both haloed, are roughly equidistant from the centre of the frame, but the Angel’s is very slightly higher than the Virgin’s; behind the Angel are slim, young tree-trunks, behind the Virgin a wall (right) and the bed of childbirth (background). The Virgin holds up the folds of her robe with her right hand, the Angel with her left. Beneath the Angel are flowers and foliage, beneath the Virgin tiles; the former appear uncrushed, so that the Angel seems weightless, whereas in the depiction of the Virgin there is a heaviness, a pulling earthwards. Immediately behind the Virgin a gold robe, also seeming to pull downwards, is draped over the back of a chair; it is balanced almost symmetrically by the Angel’s wings, composed of peacock feathers like small arrows pointing upwards. Near the base, just left of centre, is a lily, forming the bottom point of a near-parallelogram of which the other three points are another lily held as emblem of purity by the Angel, the hand from Heaven pointing down, and the dove representing the Holy Spirit. Cutting across this parallelogram is the pattern of looks: the eyes of Angel and Virgin both on the dove, which impregnates the womb. The notes supplied by the Gallery speak of the influence of Masaccio, and tell us that the picture was commissioned by the Medici family, whose device of three feathers and a ring is incorporated in the composition.

I choose deliberately here an example from a field of which I am largely ignorant. I know little about painting, less about the background to this particular painting, nothing about Lippi as man or artist. Yet I feel confident that this picture, “determined” on all levels and in every detail by the prevailing ideology, by a structure of thought and belief, by an elaborated system of signs and conventions, by the circumstances of its production, is the creation of an individual sensibility. Virtually all the same constituents—the central division, the Angel’s wings (peacock feathers), the Virgin’s drape suspended behind her, the dove, the herbage, the lily—are present in another “Annunciation,” by “a follower of Fra Angelico,” that hangs in the same room, probably painted slightly earlier. The effect is very different: to my untutored eyes much clumsier, lacking the extraordinary delicacy and refinement, the precisions of balance, of symmetry and asymmetry, of the Lippi. I have no wish to denigrate scholarship; I am sure that my response to this painting could be refined and deepened through a more meticulous knowledge of the conventions within which the artist worked. Yet I dare assert that both the picture’s “conventionality” and its unique quality can be part-deduced, part-intuited by simply studying it in the context the National Gallery provides. And I would make equivalent assertions about a Haydn symphony, or about Rio Bravo.

The digression into which I have allowed myself to wander is only apparent. The crux of this whole critical/ideological question is clearly the question of individuality—whether it exists, and what value should be placed on it; the debate about personal creativity versus determinism is inseparable from the debate about personal response versus scientific knowledge. The animus repeatedly expressed in recent criticism against the notion of individual creativity has as its necessary corollary the whole massive, formidably organized search for a scientific-objective criticism, the purpose of which is to do away with the individual voice altogether: it is in this light that the language, the vocabulary, the tactics of Screen have their real significance. This is scarcely the place for political debate (and I am scarcely a political thinker), but it is directly relevant to all my work as critic and teacher that I set supreme value on the quality—and individuality—of the individual life, cannot contemplate favourably any form of social organization that does not have the preservation and development of individuality as its end, and regard the function and meaning of art as essentially related to that concept. Life in a society from which belief in personal creativity was banished would necessarily be incapable of transcending the drabbest mediocrity; art would die in it, and with it all that which in the individual life corresponds or responds to art.

Let us be quite clear about this. Without personal creativity (both the concept and the fact) there can be no art. There may be something else—a sort of game played with counters or computers—for which some other name would have to be found.

Meanwhile, we have art to reckon with, and artists, in all their complexity and humanity. A last example: it is doubtless possible to explain, without reference to the respective individual talents (or “genius”) of Kurosawa, Ozu and Mizoguchi, how Living, Tokyo Story and Sansho Dayu (three films centrally concerned with the relationships between parents and children) all came to be made in Japan within a few years of each other. The reasons—cultural, social, political, ideological, economic—might be of limited usefulness in helping us to understand the films; to claim for them more than that is—art being in question—to mistake the peripheral for the central. Perhaps a study of socio-political-economic determinants might also explain why the dominant technical device for transitions in Living (and other Kurosawa films) is the wipe, in Sansho (and other films by Mizoguchi) the dissolve, and why both are totally absent from Tokyo Story (and other late Ozu films). I hope it is not too great an ellipse for me to jump from that observation to the opinion that to shift from the verb “create” to the verb “produce” is perversely to belittle and trivialize not only art but life.

I have come to feel, during the past few years, that Sansho Dayu and Tokyo Story may (I am careful to acknowledge a continuing uncertainty, which has several sources) be superior to any American film I know; superior even to Vertigo, to Rio Bravo, to Letter from an Unknown Woman: superior in a greater maturity of vision, and in the completeness and conscious authority with which that vision is realized. But I do not base this intimation of value on any simple assumption that Mizoguchi and Ozu were somehow mystically blessed with greater powers of personal creativity than Hitchcock, Hawks and Ophuls (just as I do not assume that the reason Mahler’s symphonies are rather different from Haydn’s is simply a matter of personal temperament). An attempt to account convincingly for the superiority (which is not the same as demonstrating it—that could only be done by examining the films themselves) would clearly involve a very thorough investigation of working conditions, the expectations brought by Japanese audiences, the conventions and traditions available to the artists, the general background and history of Japanese culture, the socio-economic-political circumstances of contemporary Japan. I would, at the same time, envisage no possible way of explaining the films’ greatness without reference to such concepts as “genius” and “personal creativity”: I would see no possibility of supposing that the films could somehow have come into being without the presence at their heart of individual creative genius.

8. The Myth of “Modernism”

The questions raised by the emphasis on avant-garde, “progressive” art can be pursued further via an examination of the conclusion to the second edition of Signs and Meaning in the Cinema. Let me preface this by remarking that, applied to works of art, terms such as “progressive” and “reactionary” have no evaluative status: they are purely descriptive. They may, however, take on a relative or transitory evaluative force in accordance with shifts and changes in society. One might argue, for instance, that in a period of revolution “reactionary” art assumes potential importance in that it embodies concepts and values that are threatened with obliteration and which might have something to be said for them.

There are two important documents by Peter Wollen on “modernist” cinema, the other being his essay on Vent d’Est in Afterimage 4. I find them very different in quality: the Afterimage article, which I take to be the later in composition, is incomparably the finer, reasonable, disciplined and illuminating—I find its position almost wholly acceptable. It is a pity that the Signs and Meaning additional chapter, because it has the comparative permanence of book form, is likely to be far more widely circulated. I am compelled to say that Wollen’s account of the difference between our “reading” of “modernist” works and the traditional ways in which art has been read, seems to me compounded of confusions, distortions and self-delusions in roughly equal measure: an extraordinary piece of frenzied mystification. In traditional aesthetics, apparently, the mind was “an empty treasure-house waiting to receive its treasure,” but the modernists force us to do some work: instead of meaning being communicated it is now “produced,” as the result of this dialogue. Wollen creates continual problems for the reader (but a compensating convenience for himself) by never allowing us any very precise idea as to what he is talking about—which works, which critics. But we can safely assume, I take it, that he would accept Vent d’Est (one of the few actual works he specifies) as a representative example of “modernism.” We might conceivably read this film in the way Wollen appears to suggest—as a sort of uncoordinated rag-bag of bits and pieces—until we have mastered the principles on which it is built. When we have mastered those principles, however, the film is no more difficult to read than Middlemarch. Correction: it is much easier to read, George Eliot’s novel making far greater demands on the reader’s intelligence and concentration. When I read Middlemarch, I enter into a continuous dialogue with it, and that is the only way to read it; the mind that is “an empty treasure-house waiting to receive its treasure” is fated to remain empty, for there is no work of art of any significance that can be adequately received by being passively absorbed. “Modernism,” according to Wollen, “produces works which are no longer centripetal, held together by their own centres, but centrifugal, throwing the reader out of the work to other works.” What works actually perform this function is not revealed: presumably Vent d’Est can again be taken as an example. The “gaps” and “dislocations” that critics now seek in traditional texts are presumably raised by “modernists” to the status of a conscious artistic principle. There are serious problems here. Obviously, any bad, incompetent work is so because of its failures—its gaps and dislocations. One could argue that an inept mystery story in which the solution is inadvertently made obvious from the beginning deconstructs itself, gives the reader critical distance, enables him to inspect the ideological structure, etc. . . . Gaps and dislocations only become of positive interest when they are felt to have constructive meaning, to be significant—when they become, that is, an aspect of the film’s coherence. This seems to me the case with Vent d’Est. Like any work of art of any value, Godard’s film challenges me to look at my assumption about life, to question my own values; it does not “throw me out of (itself) to other works,” except in the absolutely traditional sense that I am compelled to place my experience of it beside other experiences.

The reluctance to specify makes it equally difficult to pin down the distortions in Wollen’s account of traditional aesthetics:

Non-realist aesthetics . . . are accused of reducing or dehydrating the richness of reality; by seeking to make the cinema into a conventional medium they are robbing it of its potential as an alternative world, better, purer, truer and so on. In fact, this aesthetic rests on a monstrous delusion: the idea that truth resides in the real world and can be picked out by a camera. Obviously, if this were the case, everybody would have access to the truth, since everybody lives all their life in the real world. The realism claim rests on a sleight-of-hand: the identification of authentic experience with truth.

Just as it is impossible to identify these “centrifugal” modernist works, so is it impossible to grasp exactly whom Wollen is talking about here: who is supposed to hold this incredibly naive and silly position? Simply to place (say) Hawks’s films beside Bergman’s is to realize that they can’t both be presenting an absolute, objective “truth”; to add a third term to the comparison would be to suggest that neither does. Simply to speak of an artist’s “view of life” is implicitly to recognize that he is not imparting “truth” in Wollen’s sense. “Authentic experience” is obviously one of the things the critic is concerned to identify and evaluate—with all the complexities and qualifications that will involve. But who identifies it with “truth”?

These arguments are elaborated to justify a commitment to an avant-garde that appears barely to exist: apart from recent Godard, no one is allowed in it without reservations. The commitment, none the less, is extraordinarily intense: “it is necessary to take a stand on this question and to take most seriously directors like Godard himself, Makavejev, Straub, Marker, Rocha, some underground directors . . .” There is a very curious passage about the potential “destructiveness” of texts: “Ulysses or Finnegans Wake are destructive of the nineteenth-century novel,” but destructive in what sense is not clear: obviously they have made it difficult to write nineteenth-century novels, but one hardly needs to be told that, and one suspects that Wollen means it has also made it irrelevant to read them. I find the whole paragraph (pages 171–72) extremely confused and confusing. One can give most of the statements, considered separately, a guarded assent, but the overall argument remains partly unintelligible. The passage culminates in this: “A valuable work, a powerful work at least, is one which challenges codes, overthrows established ways of reading or looking, not simply to establish new ones, but to compel an unending dialogue, not at random but productively.” I am not clear as to the exact distinction implied by that “at least” between “powerful” works and “valuable” ones: I suppose a powerful work might not necessarily also be valuable, but value seems implied by the rest of the sentence. It is obviously true that a great artist—an artist, that is, who achieves, through pertinacity, integrity, discipline, dedication and personal genius, a truly individual voice—modifies our sense of all that has gone before, forcing us to readjust; and obvious too that the history of art is a history of continuous transformation and development. But many of the greatest artists have been as much consolidators as innovators. Bach and Haydn, for example, scarcely “overthrew established ways” of listening: they built on the formal procedures and established idioms with which their audiences were familiar, developing and extending their possibilities. There may be ways in which the B Minor Mass (which I take it would be generally accepted as both “valuable” and “powerful”) “challenges codes,” but any account of it that saw its significance exclusively or even primarily in such terms would surely be extremely partial. It becomes difficult to separate Wollen’s arguments decisively from the most naive belief in progress, from a sense that only art that can be unequivocally associated with “progress” is valuable, and finally from a desperate commitment to the latest thing, irrespective of quality. Welles, for example, has come to look “hopelessly old-fashioned and dated,” apparently because it can now be seen that he was only an innovator within a certain context (true, I would have thought, of most innovators). Wollen actually lets himself get carried (there is a general sense of someone not really in control of his ideas) to the point where he finds it necessary to warn us that Hollywood should not be “dismissed out of hand as ‘unwatchable’” (whom can he be warning of this except himself?). Works that challenge existing codes may make those codes unusable, but they are not destructive of previous works that employed those codes: no one could or would wish to write a Middlemarch today, but Middlemarch is not thereby invalidated. What is destructive is a view of art that insists that its only real interest lies in its destruction of the past, and that sees the critic’s first priority as a frantic quest for the latest thing.

One of the greatest “progressive” artists of the present century saw things rather differently: “His lessons were very interesting. He never said a word about the twelve-tone system. Not a word. He looked through what I had written, he corrected it in a very wise manner, and we analysed Bach motets” (the late Dr. Otto Klemperer on Schönberg).

9. In Defence of Vent d’Est

Part of the problem raised by Godard’s recent work can be suggested by the question, “Whom are the films for?” The obvious answer, supplied by Godard and Gorin themselves, is for a small educated Marxist élite. With this goes the implication that the films are almost instantly disposable: revolutionary tools made for a specific local purpose, redundant as soon as that purpose has been served.

Related to this is the question, “Whom am I writing this for?” Not, certainly, the Marxist élite equipped to welcome Vent d’Est without pain, or bewilderment, or confusion. Nor, really, those who profess to find the films merely “boring”—unless they are prepared to re-think them (or, rather, think them, for their reaction suggests an abeyance, or even a deliberate withdrawal, of thought). Perhaps the prime audience anyone writes for consists of people who reflect the writer’s own degree of uncertainty. The question that most interests me (and about which I am very uncertain) is, how does a critic who is not a Marxist, or a Marxist-Leninist, or a Maoist, cope with recent Godard honestly?—and how does he do critical justice to an artist who has renounced art (short of renouncing him)? The Marxist answer will be, presumably, that of course he cannot, as bourgeois ideology is an edifice of lies and anyone who is not a Marxist is a bourgeois (including the workers, who would far rather see Bonnie and Clyde than Vent d’Est). Those of us who are sensitive to the enormities of capitalism, yet fail to find Marxism an acceptable alternative, may feel that the problem is not so simple. One is helped and encouraged by one’s intermittent recognition (despite appearances to the contrary) that Godard doesn’t always find problems simple either. His early work, up to Pierrot le Fou and a bit beyond, can be seen in terms of, above all, an effort to define and hold in balance his uncertainties: “Je ne sais pas,” opening line of Le Mépris and Une Femme Mariée, is an appropriate motto. And, although the bounds of his uncertainty are now more securely fixed, more narrowly defined, a decent tentativeness, a refusal either to assert or to bully (qualities temporarily submerged in the tense repressiveness of Vent d’Est), resurface in Tout Va Bien. People in his films assert all the time, but that is clearly not the same thing: except when Vladimir and Rosa supervene, it is difficult to think of a single statement (beyond that of uncertainty, perhaps) delivered in a Godard film that can be unequivocally construed as “Author’s Message”: the statements are set side by side as so many pieces of evidence for our serious consideration, Godard’s point of view being defined only in terms of the areas of interest implied by the selection.

The paradox of the “artist who has renounced art” is central to the critic’s problem. There is a sense in which any film is a work of art and cannot not be, since some organizing principle must be in operation. Yet there are a great many films (e.g., newsreels) where what one must call (recognizing that the term begs certain questions) the “aesthetic” response is scarcely appropriate, or not appropriate as prime consideration, as the central focus for discussing our experience. The “aesthetic response” is not, for me, something separable from our whole response as human beings: indeed, its nature is defined by this wholeness. But it also represents the critic’s way of attempting to achieve a relative impartiality, to see and evaluate the work apart from shared or disputed particularities of dogma or creed. The opposition between “work of art” and “revolutionary tool” may seem at first glance illusory, but I find it inevitable. Revolutionary tools and works of art are subject to completely different evaluative systems, because they invite a different sort of response. The former invite to direct action (and invitations to direct action form a significant part of Vent d’Est’s raw material); the latter does not ask us to do anything, the response it aspires to elicit being altogether more complex. A work of art may affect our lives deeply and permanently, but it takes other forms of discourse—reasoned argument, slogans, direct exhortation—to send us out into the streets. As soon as we respond to a work as an organic (or at least organized) whole—respond to what it is rather than what it says—then formal questions of structure, order, balance, assert their pre-eminence, and the possibility of effective exhortation accordingly recedes. Such a distinction does not emasculate art; rather, it insists upon its much greater, less ephemeral (if also less precisely directed) potency.

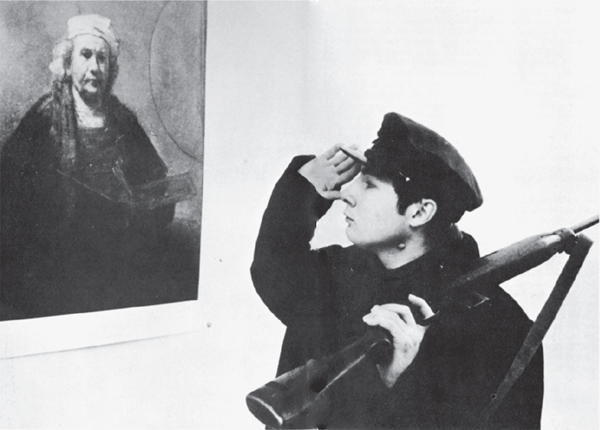

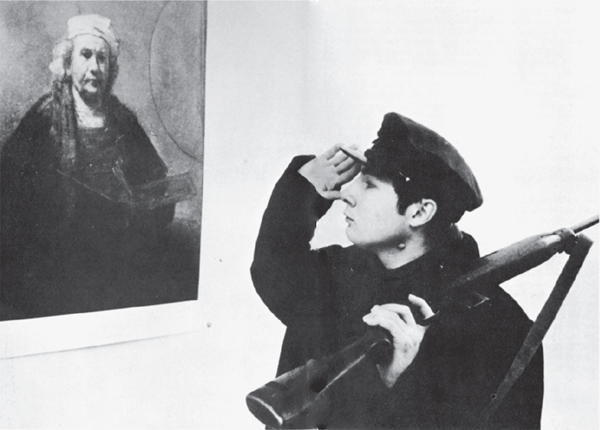

The prime purpose (explicit in statement, implicit in formal procedures) of Godard’s “politicized” cinema is not to create “complete” works of art for the aesthetic (moral, emotional) satisfaction of the beholder, but to stimulate or provoke to revolutionary activity.2 Godard’s radicalism has led him repeatedly to demand and announce a “return to zero”: the revolution is not against certain incidental injustices of capitalism, but against the whole development of Western culture over (at least) the last two thousand years. What Godard’s attitude now is to the art of the past is not entirely clear to me; it was always somewhat equivocal. The early films swarm with “artistic” references, like fragments Godard wished to shore against his ruin, or emblems of allegiances by means of which he would establish an identity. Yet it was never certain just how deep a commitment this magpie agglomeration represented: one might doubt whether it meant to Godard, for example, what Bach evidently means to Bergman. The references were always external and explicit: the Bach fugue picked out on the piano in Wild Strawberries points us to the structural principle of the entire film; Haydn in Le Petit Soldat is just a record on the gramophone. Retrospectively, it is easy to see that Godard was already, at least in negative terms, prepared for the step into Marxist politicization: he had already formed the habit of regarding the arts as so much material to be pillaged intellectually rather than as offering enriching experiences to be assimilated into one’s inner emotional-intuitive life, and it is much easier to pass to a strictly ideological analysis from the former attitude than from the latter. The apparent rejection of art in Godard’s recent films could be felt to have been implicit already in Les Carabiniers, where the soldiers react briefly to a Rembrandt self-portrait and a Madonna-and-child but remain permanently or deeply affected by neither: the point of the scene was the uselessness of art in relation to society at large, a sort of visual epitome of the view of George Steiner discussed earlier. From Masculin-Féminin onwards, artistic references give place increasingly to political references; after Weekend they virtually disappear from his work or (like the western in Vent d’Est) are referred to with a view to ideological exposure and denunciation.

A soldier in Les Carabiniers reacts to the Rembrandt self-portrait.