17

Voters

I remember, when I first moved there in 1964, I was just married and looking for a house. And I can honestly say, this is the first time that I personally encountered people who said, ‘We don’t take any blacks here.’ I had been living insulated from that. I’d been a student, living in college or living in student housing. I hadn’t encountered that, personally. I knew it was going on, but this was absolutely straight, ‘No blacks here’, ‘We don’t take any blacks’, et cetera. And people shouted at us in the street when we were going around trying to find places, you see, myself and my white wife. You can imagine. She was the particular object of vile remarks about mixed race couples, and so on. So, I had a very bad introduction to the West Midlands, I must say. And I have always thought, it may be wrong, but I’ve always thought that I could understand that Powellism would have come out of the West Midlands. I thought one could hear a particular kind of resentment, deep resentment, almost as if we’d been left behind by England and now we were going to be left behind in relation to race, you know, permanently left behind. And that’s a historical resentment, latched on to race …

Stuart Hall (1998)1

The Notting Hill riots marked one of the first moments when racial prejudice was openly, and violently, expressed in Britain. For West Indian migrants in particular, those who had felt a compromised sort of belonging to British culture, the riots spelled the end of uncertainty. They now knew incontrovertibly that they were ‘coloured’ outsiders. And though large swathes of the population felt sympathy for the immigrants, and the liberal establishment expressed that sympathy, the government did nothing to harness it for change. A number of hopeful cross-community projects which were mooted in the immediate aftermath of the violence fell by the wayside. The extra funding for deprived areas, the house-building projects, the school pilot programmes – none of them materialized. There was no special provision for the reception, briefing, placing or housing of immigrants at all. There were no laws against racial discrimination. The focus lay on teaching the immigrants how to integrate more successfully (partly through BBC English language and culture programmes), rather than on teaching locals not to hate. And it was fear of this unchecked and growing anti-immigrant sentiment which led the Conservative government to introduce the Commonwealth Immigrants Bill in 1961.

Six years after the riots, in the 1964 general election, the success of Peter Griffiths’ openly racist campaign for the Smethwick constituency dealt another blow to Britain’s idea of itself as a tolerant country that was, on the whole, managing to absorb its minorities in an orderly fashion. The result in Smethwick has been seen as a turning point in the history of British racism, the first time that race and immigration explicitly formed part of a mainstream electoral appeal. Griffiths was not standing for Mosley’s Union Movement or for the British National Party, but for the Conservatives. His victory, with 47.6 per cent of the vote to Patrick Gordon Walker’s 42.6 per cent, defied the national swing to Labour, and it appeared to have been achieved purely by appealing to popular resentment and fear of immigrants. Interviewed by Robin Day for the BBC on election night, the Conservative peer Robert Boothby denounced the result as ‘the most disgusting thing that has ever happened in British politics in, certainly in our time and probably for the last 200 years. It’s revolting, Smethwick.’ Harold Wilson condemned the campaign in the Commons, insisting that, ‘Smethwick Conservatives can have the satisfaction of having topped the poll, of having sent a Member who, until another election returns him to oblivion, will serve his time here as a Parliamentary leper.’ In fact Griffiths represented Smethwick for only two years. In the 1966 general election the constituency was won by the Labour candidate, the actor Andrew Faulds.2

The liberal establishment was shocked by the 1964 result, but black and Asian immigrants living in the West Midlands were less so. They had seen it coming. And at least some of them were sceptical of the amount of clear water between the two candidates when it came to matters of race anyway. When Gordon Walker stood again (and lost again) in the Leyton by-election in January 1965, a reporter for the short-lived Caribbean journal Magnet asked local West Indians what they thought of him.

Mr James Roland, a 28-year-old Jamaican resident of Leyton, had this to say about why he did not vote in the by-election: ‘As far as I am concerned it was a choice between Caesar and Caesar. I remember this man Mr. Gordon Walker from the days when he exiled Seretse Khama because the South African Government was putting pressure on him. I read about it back home and I don’t think he changed all that much since then, and as for the other candidates, they were talking in such a soft voice about people like me that I never heard them. So who did I have to vote for?’ Mr. Roland’s opinions must be taken seriously because this general ‘it has nothing to do with me’ attitude is fairly wide-spread in the coloured community.3

Roland was remembering Gordon Walker’s role as foreign secretary in forcing Seretse Khama into exile. Khama was a prominent royal in what was then the British Protectorate of Bechuanaland, who would later become president of Botswana. He was exiled because of his interracial marriage in 1948 to Englishwoman Ruth Williams, whom he had met while training to be a barrister at the Inns of Court in London. This capitulation to South Africa’s apartheid regime was hardly what Gordon Walker was expecting, still less hoping, that his potential voters would remember.

In 1964 the Conservatives had been in power for thirteen years. They fought the election promising more of the same: stability, the protection of the family, low taxes, secure pensions. In contrast Wilson’s new look, ‘white heat’, Labour Party promised all the fruits of modernity, investment in industry, house-building programmes and a rejection of the Conservatives’ play-safe mode. The election in that October – called a full five years after the last one – was the first to follow the passing of the Commonwealth Immigrants Act. All three of the main parties avoided making immigration central to their campaigns, avoided getting involved in what Roy Jenkins called ‘coloured politics’ (‘one party on the side of the coloured and the other against’). Arguably this was as much about pragmatism as moral responsibility. Courting the anti-immigrant vote meant alienating immigrants, and the Commonwealth powers from which they came. But wooing the immigrants meant being branded as ‘the immigrant party’. And neither Labour nor the Conservatives felt on particularly strong ground on the issue of immigration. The Conservatives had pushed through the 1962 Act in the teeth of Labour opposition, but two years later there was widespread feeling in areas of high immigration that the Act was too little, too late. It was poorly designed and impossible to enforce; in places where the main immigrant group was Irish, such as in Deptford, locals argued it was worse than useless. It had done nothing to alleviate their problems. Meanwhile Labour trod a very fine line. They had opposed restrictions in 1961, but it was political suicide to present themselves as friends of an ‘open door’ policy. Labour candidates in immigrant areas were reduced to bleating that most of the newcomers had arrived under the Tories. The Labour manifesto was woolly about policy too. Unlike the Tories, who professed to be worried that making discrimination illegal might give people ideas, they promised to ‘legislate against racial discrimination and incitement in public places and give special help to local authorities in areas where immigrants have settled’. But they also accepted the principle of the need for restrictions on new arrivals. What they wanted, they said, was to negotiate an agreement with Commonwealth heads of state. But in the meantime, in the absence of such agreement, the Act to which they had objected should stay: ‘Labour accepts that the number of immigrants entering the United Kingdom must be limited. Until a satisfactory agreement covering this can be negotiated with the Commonwealth a Labour Government will retain immigration control.’ In fact, once in power, the Wilson government unilaterally tightened restrictions on newcomers from the Commonwealth.

There was tacit agreement at policy level not to play the race card. But there was nothing to stop local candidates talking up immigration. As shadow foreign secretary, Gordon Walker had fiercely denounced the Commonwealth Immigrants Bill during readings in the Commons. He had accepted that racial tension was rising in areas of high immigration, but argued that the Bill would do nothing to stop that. ‘If we do nothing else but just have this Bill, the problem will get steadily worse.’ Instead, what was needed was help for local authorities in immigrant-occupied areas. Peter Griffiths made the most of his opponent’s soft line, insisting that ‘Labour was backed by the immigrants’, and that he alone spoke for local people who were weary and fearful of the immigrant burden they had been asked to bear. Griffiths campaigned on a platform of speaking truth to power. Local people wanted immigration stopped, and ‘if it suits the people of Smethwick I will say it’. He proposed a ban on all immigration for five years, and deportation of criminals and the unemployed. He argued for separate school classes for immigrant children who struggled with English, and he insisted that immigrants had brought violence, crime and disease to Smethwick.

We believe that unrestricted immigration into this town has caused a deterioration in public morals. We have no objection to a man who happens to have a coloured skin, who looks after himself and his house decently, and who works. But this town is not to be the dumping ground for criminals, the chronic sick, and those who have no intention of working.

In July 1964, as the seventeen-year-old Jamaican star Millie topped the charts with ‘My Boy Lollipop’, Griffiths argued in the local paper that, ‘Smethwick rejects the idea of being a multi-racial society. The Government must be told of this.’

By 1964 there were 800,000 New Commonwealth immigrants living in Britain, about 1.5 per cent of the population as a whole. Smethwick was then a town of 67,000 people, of whom 4,000–5,000 (around 6 per cent) were immigrants. Just over half of the immigrants were Indian – mainly men working in the iron foundries – 37 per cent were from the Caribbean islands, and 9 per cent were from Pakistan. This figure was much higher than the national average, though there were greater concentrations – for example in Southall, where the immigrant population was more than 11 per cent. A contemporary account of the Smethwick campaign by social scientists at Birmingham University (carried out for the Institute of Race Relations) suggested that part of the hysteria over numbers may have been caused by the fact that many more immigrants arrived each day to work in the network of foundries that dotted the northern part of the town. And what was apparently the largest gurdwara in Europe stood on Smethwick High Street, attracting Sikh worshippers from across the West Midlands. The housing conditions in the area were very poor, with people living at a density of 27.4 people per acre, and more than four thousand people were on the council housing waiting list. Both Liberal and Labour candidates argued that the root cause of the problem was inadequate housing stock, but many local people blamed the immigrants. In June 1961 the tenants of Price Street had threatened a rent strike against the Labour council for rehousing a Pakistani family (whose home had been demolished under a slum-clearance scheme). Conservative councillors hurriedly sketched a policy for a ten-year residence qualification, with Griffiths arguing that ‘many people who have been in this country only a few months snap up houses they know are due for demolition’. In 1963 another Tory councillor had set up ‘vice vigilante’ patrols through the immigrant areas. And as a researcher for the Institute of Race Relations argued, the fear and resentment of newcomers were actively amplified by the local paper, the Smethwick Telephone, whose pages were filled with anti-immigrant letters and opinions.4

One of Griffiths’ electoral strengths was that he was a local man – a West Bromwich headmaster who spoke with a regional accent, he styled himself as a lone voice prepared to acknowledge the concerns of local people. And the media certainly enjoyed showcasing the locals during the campaign, or gawping at them. The BBC news aired reports in which working men said to camera: ‘The blacks have come here to exploit the whites’; ‘It’s full of niggers. We don’t want them in Smethwick. We want to get them out!’ Griffiths was unapologetic about lifting the lid on this racism, arguing that in Smethwick the Conservative Party was ‘acting as a safety valve – a function which otherwise might have been taken by the extreme right’. His opponents argued that what he was doing was legitimizing racist and anti-immigrant attitudes. A comparison with other constituency campaigns where immigration was an issue suggests that they were right.5

In Brixton, for example, where the Union Movement and Keep Britain White had been active through the 1950s, and where there had been a council-housing rent strike similar to that of Smethwick’s Price Street, the swing to Labour was one of the highest in the country. Analysts argued that this was partly because the local paper, the South London Press, was not the Smethwick Telephone. Although it printed plenty of letters and articles critical of immigrants, it also gave ample space to West Indian residents objecting to prejudice and misinformation. Was part of the problem in Smethwick that the largely Asian immigrants did not fight back through the British media, but organized among themselves? The example of Southall suggests otherwise. Many of the same social ingredients were stirred up together in Southall’s pot, including a local attempt to ensure that vacant properties were sold only to white buyers, and requests from residents for segregated schools. (Rejecting these requests in 1963, the minister for education, Sir Edward Boyle, laid down the principle of dispersal (bussing), with a maximum immigrant quota of one-third per school, a policy which was to prove almost as controversial.) But in Southall the immigrant card was played not by any of the main parties but by the British National Party (BNP), which had formed in 1960 through a merger between the National Labour Party and the White Defence League, and had polled well in some local elections. The BNP leader John Bean built his ‘Save Our Southall’ campaign around a familiar raft of measures: stop non-European migration, pay for repatriation and give no National Assistance to unemployed immigrants. Immigrants brought disease and a high birth-rate, and ‘Once our stock has gone, it has gone forever,’ he warned. He was helpfully explicit that the ‘Northern European stock’ he favoured included the Irish, the Poles and the Jews. He polled 9.1 per cent, and appears to have drawn his votes almost equally from both the Conservative and Labour candidates.6 The difference between Smethwick and Southall was that Bean was a fringe candidate rather than a mainstream politician making political capital out of immigration. Asian immigrants in Southall knew that nearly 10 per cent of their neighbours wanted to get rid of them, and probably many more would rather they went away. But in Smethwick it was nearly 50 per cent; the Conservatives under Peter Griffiths had made it seem acceptable to hate immigrants.

A few miles from Smethwick, Birmingham’s Sparkbrook (where there were an estimated 10,000 immigrants, half of whom were Irish) faced a similar housing crisis. Immigrants were crowded into large, decaying, single-room lodging houses and the locals were crowded into working-class terraces, many of which were scheduled for slum clearance. With large numbers of residents working at the Longbridge car factory there was plenty of money but few amenities. More people owned cars than had bathrooms. In 1959 the Conservatives had won Sparkbrook from Labour by a narrow majority (886 votes). But in 1964 Roy Hattersley won the seat back for Labour, with a swing of 3.3 per cent, the largest swing in Birmingham, after what was described as ‘a very quiet campaign’, with ‘barely a hint of racialism’. The campaign successfully located the problems faced in Sparkbrook as rooted in housing rather than immigration, though one commentator suggested that the fact that the majority of immigrants – the Irish – were hard to pick out in a crowd might have had something to do with it:

The Irish are the largest immigrant group, in Sparkbrook as in Birmingham, but in some ways they are the hardest to discuss. To many, of course, they do not appear as immigrants at all. They are the same colour as us; they’ve come from just across the water; they speak a kind of English. But often those living in immigrant areas regard them as their greatest trial. Whether they are from the Dublin slums or from the bog, they were not born to the highly disciplined, restrained life of the English city. They have not yet begun to adjust to their proletarian life as their respectable hosts in Sparkbrook have, and they still construe the world as a running fight between ‘them’ and ‘us’.

Nevertheless, they are not readily identifiable – a drunken Irishman looks very much like a drunken Englishman from a distance.7

A more plausible account was that the Irish, almost alone among post-war migrants, were actively involved in British domestic politics. Not only were they registered as voters, but they were active in the local wards. The Grenadian Labour politician David Pitt, who had stood unsuccessfully for Hampstead in the 1959 election, argued that West Indian immigrants had good reason to be suspicious of British electioneering:

They refuse to join political parties because they are often invited to join when elections are in the offing, and they feel that the invitation to membership is merely a ruse to safeguard their vote and they strongly resent being used … Many immigrants do not get their names on the electoral roll because they feel that they are being spied upon and the attempts to get them on the electoral roll are merely a way of trying to be sure of their whereabouts. The landlords think it is a means of trying to find out their incomes and do not put their tenants’ names on the roll. The tenants believe they are safer if their addresses are not known.8

Arguably it was even harder to register Asian voters, who were not only keen to stay under the official radar, but often had poor English. In Southall in 1964 the Indian Workers’ Association (IWA) responded to what they saw as the racism of the Southall Residents’ Association (which was lobbying for white-only property sales) with a concerted effort to sign up Indian voters – and to recommend them to vote Labour. They produced pamphlets explaining the vote in Punjabi and Urdu, and gave voting demonstrations before screenings at the Dominion Cinema. They manned the polling stations with helpers who could explain the voting slips. The Birmingham IWA was active in getting the Indian vote out in Smethwick, and the two Birmingham marginal constituencies of Sparkbrook and All Saints. They produced leaflets in Punjabi, carried out advance canvassing, and on election day sent out teams to target Asian electors (whose names were easy to spot on the electoral roll) across six wards:

During the day there were nine workers with four cars engaged specifically on the task of getting Asians to the poll; in the evening there were eighteen people and twelve cars, including two large vans. The daytime aim was to get as many women as possible to vote, and the team included three women for this purpose … Mr Jouhl is confident that practically all Indians voted for Gordon Walker, his workers having at great pains made clear to them that the ‘X’ should go in the second line down.

The headline in the Birmingham Mail read, ‘Smethwick’s Immigrants Flock to the Polls’.9

The 1964 election marked the beginning of Asian involvement in British politics and race relations. The Indian and Pakistani Workers’ Associations had initially been formed to provide support and advice for men arriving into an unfamiliar and often hostile environment. The IWA’s first major campaign was to lobby the Indian government on behalf of those who had arrived on forged passports, and who were therefore unable to get on the right side of the law. By the late 1950s the problem of returning home on forged papers had introduced a new racket, which involved bribing officials in the Indian High Commission in London to renew forged passports or to issue valid ones in exchange for forged ones. In 1960 the IWA took advantage of a state visit to Britain by Jawaharlal Nehru to lobby for change, and the High Commission agreed to issue valid papers to anyone who turned in forgeries.

In the early years the IWA functioned mostly as a social support agency, an Indian citizen’s advice bureau where people could get help with form filling, applications, mortgage advice and legal guidance. The leaders were mainly men who had been active in the Communist Party of India (CPI). (Those who joined the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) caused a headache for British Communist leaders as they set up separate branches and held their meetings entirely in Punjabi. The men sent along from CPGB local branches listened uncomprehendingly to discussions of how to support the CPI in Indian elections.10) Ordinary workers were often sceptical of this political bias, and many had to be strong-armed or cajoled into joining.

Back in the early days it was not easy to get people to join the IWA. You know Harbhajan Singh? I had a very difficult time getting him to join. He said that the IWA could do nothing, it is a waste of time; and he wouldn’t join. So one day I met him in the cinema and argued with him and then I said, ‘Will you give me 2/6’ (the membership fee). He said, ‘Yes, here it is, but I won’t join.’ So I took the 2/6 and enrolled him as a member.

One local organizer in the West Midlands explained how the association gathered support:

We rented a hall or a room in a pub and people would come and drink and sing. For the first half hour or so, the committee members would have to stand up and sing, but after that the other people would join and everyone would be singing. It was a very good time and everyone enjoyed it. We held three or four of these socials and after a while there would be two hundred people there, everyone enjoying themselves. Then we started a membership campaign for the IWA and everyone joined.11

According to Avtar Singh Jouhl, leader of the Birmingham IWA in the early 1960s, the cultural side of the Indian labour movement also attracted people associated with the left-wing folk protest movement and the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, including the radio balladeer Charles Parker, and folk musicians Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger. Other branches ran film shows to attract new members. The advantage of these new secular organizations – the Pakistani Workers’ Association operated in much the same way – was that they offered men the opportunity to create new ties which cut across village lines, providing an alternative to village and caste-based community leaders. Later, as more and more migrants arrived from non-Jat groups (such as Valmiki or Ramgarhia) this secular, politicized community would be divided again, as religious groups affiliated to new caste-based temples and gurdwaras took over the role of community centres. But for a period in the early 1960s, the workers’ associations held the balance of power within the Asian communities.

There were two factors which propelled the Asian labour movements forward. The first was the greater sense of security felt by the majority of workers once the Indian government lifted restrictions on the issue of passports. Once their papers were legalized they could turn their attention to campaigning against unfair dismissal and segregation in the workplace. Several factories in the West Midlands had installed separate Asian and European toilets, for example, but it was only possible to persuade men to complain about such things once they felt safe in their jobs. The second factor was yet another unintended consequence of the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act. Indian, Pakistani and West Indian groups collaborated on protests against the proposed legislation. Once the Act was passed, with future right of entry to Britain now restricted and immigrants increasingly deciding to make their move permanent, it made sense for them also to accept that they were part of Britain’s working class.

During the 1950s trade unions had often lodged objections to Commonwealth labour as bound to lower wages and conditions for the workforce in general. In a situation where Indian and Pakistani workers were regarded as the enemy of the British unionized worker, it made little sense for Indians and Pakistanis to agitate to join the unions themselves. (The opinions of Bradford millworkers interviewed in the early 1960s were representative: ‘They stand for English workers.’ ‘They don’t want to include us – they are prejudiced and seek to exploit us.’ ‘I have never heard of a union being helpful to an immigrant when he was sacked or ill-treated.’12) But this gradually changed, in part because immigrant workers saw the advantage of campaigning for better conditions, and in part because, facing declining membership, the unions themselves began to court Asian members. By the mid-1960s the Amalgamated Union of Foundry Workers was liaising with the left-wing Indian workers to get their compatriots to join up in the West Midlands. In 1966 the first major strike by Asian workers was organized by men protesting against the conditions inside Woolf’s rubber factory, but it had taken years to get that far. As one factory worker recalled:

There had been a lot of talk about forming a union. The feeling against it was not that it would be bad; the conditions in the factory were terrible and everyone thought that a union would help. But everyone was afraid that an attempt to organize would fail and everyone would be fired.

That was exactly what had happened in 1960. Men of the IWA had recruited 316 out of 600 workers to the union, but one of the foremen had informed the owner, who had got rid of the agitators.

In every shop there were one or two men who were friendly with the management. They were touts for the foremen. They would find men who wanted a job and take them to the foreman. To get a job, you had to give a bribe, and the foreman would split it with the tout. Everyone was afraid that the touts would tell the foreman who had organised the union and then the foreman would give them the sack.

In 1964 they tried again, but they made sure to sign men up to the union outside the factory, and most often in the privacy of their own homes.13

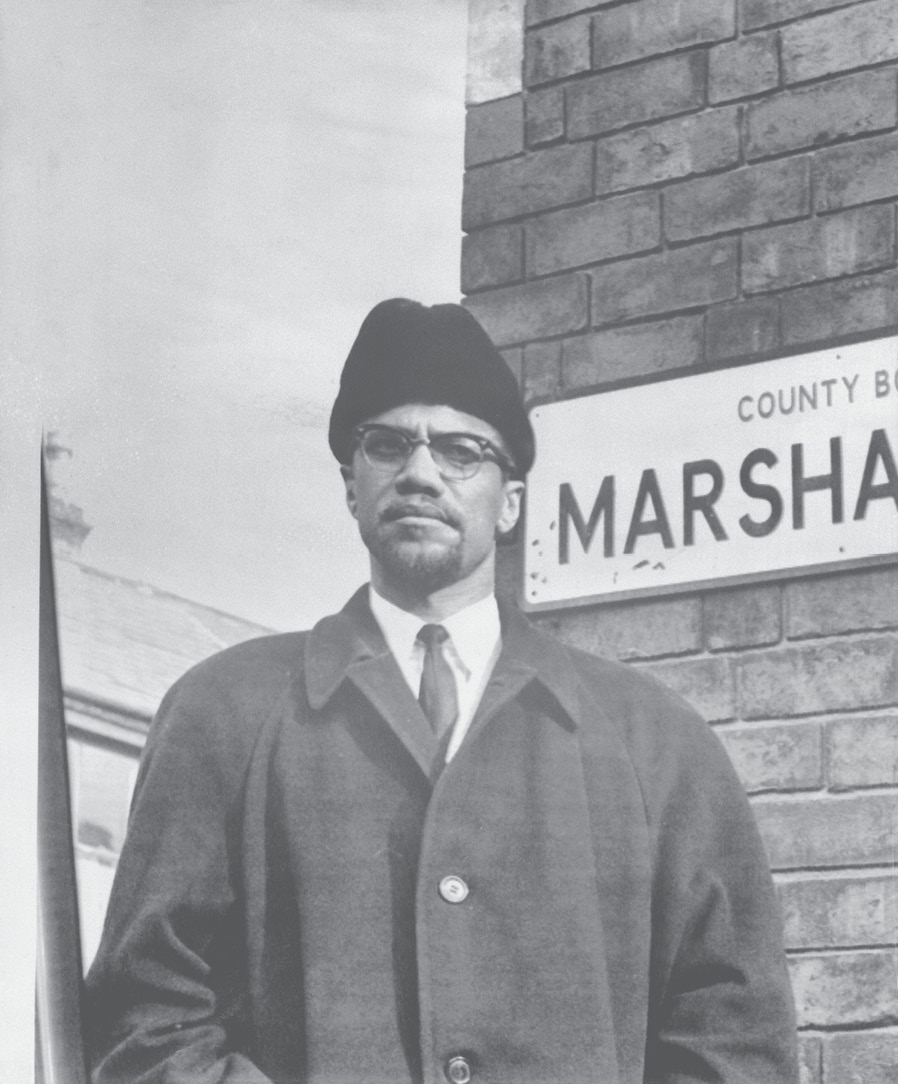

This increased radicalism was given articulate expression in February 1965, when Avtar Jouhl invited Malcolm X to Smethwick. The Black Power activist had been a prominent member of the Nation of Islam but by 1964 had broken away to form his own religious and civil rights organizations, Muslim Mosque, Inc. and the pan-Africanist Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU). In February 1965 he was in London to address the first meeting of the Council of African Organizations. Nine days before he was murdered in New York he was filmed by the BBC in Smethwick, despite the mayor, Alderman Niven, stating publicly that he did not want ‘this algebraic character’ stoking racial tension on the streets of his town. (He was accompanied on the trip by a second algebraic character, Michael de Freitas, who was introduced as Malcolm’s ‘Brother’ Michael X, although he was to change his name to Michael Abdul Malik when he converted to Islam a few weeks later.) As the Birmingham Post reported, ‘When asked why he had come to such a minor town, Malcolm X replied, “I have heard that the blacks … are being treated in the same way as the Negroes were treated in Alabama – like Hitler treated the Jews.” ’ To the Wolverhampton Express and Star he complained:

From what I understand, Colin Jordan [founder of the National Socialist Movement in 1962] can go to Smethwick and strut up and down Marshall Street and other streets preaching ‘if you want a nigger neighbour vote Labour’ and that’s all right. As long as it is the Fascists and Nazis, it seems everything’s O.K. but when I go to Smethwick there are protests. Britain has a colour problem and I give white Britons credit for realising it … I am just shocked that there are some people like this Mayor of Smethwick who object to my being there.14

Malcolm X’s appearance in Smethwick took place at the same time as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee organized their campaign for voting rights for African Americans in Selma, Alabama, and just one month before Martin Luther King’s famous speech at the conclusion of the civil rights march to the state capital, Montgomery. United States racial discrimination was in the news, and by arguing that the black community in Britain must stand up for itself Malcolm X suggested parallels with the situation in the States. He made no distinction between West Indian and Asian immigrants, and implied that the racism they faced on account of their colour could unite them. His frank admission that ‘Britain has a colour problem’ was one way of insisting on the need for immigrants to campaign for their rights as black people rather than as immigrants. It was language which had, until this point, been owned by the white supremacists and it certainly made many people, including the mayor of Smethwick, uncomfortable to hear it in the mouths of black people themselves. When Peter Griffiths had won the Smethwick election four months beforehand he did so by ignoring the immigrants – his battle was not with immigrant opinion but with those in the Conservative Party who disagreed with his line on keeping them out. But Commonwealth immigrants were beginning to organize around a consciousness of themselves as black. Why not inhabit the stereotype, and turn it back against the people who were trying to define you? Philip Donnellan’s 1964 documentary about the West Indian community in Birmingham, The Colony, included an interview with an immigrant from St Kitts, Stan Crooke, who suggested that the experiences of the immigrants were teaching them new ways of thinking about themselves: ‘The West Indian no longer considers himself a Jamaican, a Trinidadian, Barbadian, Kittian, Antiguan. We are all subtly but inexorably considering ourselves as all coloured people.’15 Malcolm X implied that Asian migrants were also a natural part of this black alliance.

The wisdom of this stance appeared to be proved later that summer when the Labour government published its White Paper on Immigration, a document which did nothing to decrease the amount of political radicalism in the Birmingham Indian Workers’ Association, and which took moderates by surprise. The Economist labelled it a ‘Black Paper’. Commonwealth immigration was to be slashed to 8,500 category A and B voucher holders per year. Unskilled migration from the Commonwealth (the category C vouchers) was to be stopped altogether, while European and Irish immigration went on unchecked. (There had been a 30,000 net increase in migration from Ireland in 1964.) Other clauses recommended deportation of immigrants at the home secretary’s discretion, with no recourse to the courts – raising protests that this would constitute a fundamental encroachment on human rights. ‘Britain accepts the Colour Bar’, wrote Mervyn Jones in the New Statesman on 6 August. He pointed out that the government was encouraging a brain drain from Commonwealth countries, while refusing entry to unskilled workers unless they were Irish. The Spectator called the document a ‘surrender to racial prejudice, vilely dressed up to appear reasonable’. David Pitt accused the government of ‘pandering to what they believe are the prejudiced views of the electorate’.

Harold Wilson was unapologetic. He argued that the White Paper was motivated neither by colour nor by racial prejudice. Instead it provided the bulwark against it. The government had a duty to act on Commonwealth immigration in order to forestall ‘a social explosion in this country of the kind we have seen abroad. We cannot take the risk of allowing the democracy of this country to become stained and tarnished with the taint of racialism or colour prejudice.’16 Like Malcolm X, Wilson was taking his lesson from the United States. The government did set up the Race Relations Board in 1965, and introduced the first of a series of laws outlawing racial discrimination in public places – including hotels and restaurants but not shops, or lodging houses, where in practice immigrants were most likely to come face to face with discrimination. But in restricting Commonwealth immigration still further Wilson’s administration had accepted the basic premise that immigrants – and black immigrants in particular – were the cause of social unrest. It was easier to stop them arriving than to address the problems of discrimination and prejudice at its other source: in the ugly, depressed and intolerant mood that Stuart Hall found when he moved to Birmingham in the summer of 1964, a resentment that had ‘latched on to race’.